Pandora’s Box of AML: How TP53 Mutations Defy Therapy and Hint at New Hope

Abstract

1. Brief Introduction

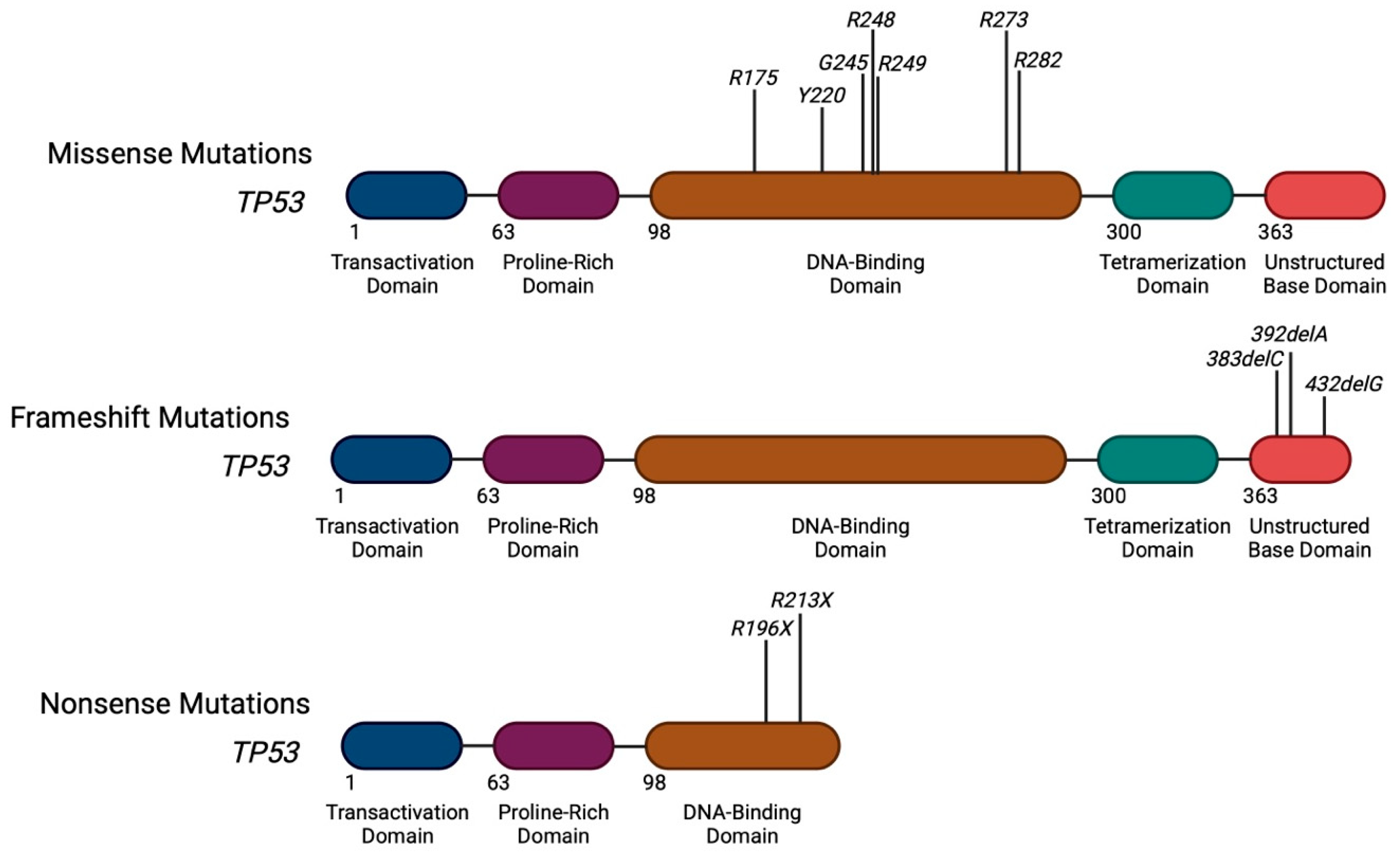

2. Heterogeneity of TP53 Mutations in AML

Distribution of Mutations Along the TP53 Gene

3. Clonal Architecture of TP53 Mutations in AML

3.1. Technical and Genetic Screening

3.2. Allelic Complexity of TP53 Mutations

3.3. Somatic and Germline Co-Mutation Profiles of TP53 Mutant AML

3.4. Prognostic Impacts of TP53 Allelic Burden and Co-Mutation Frequency

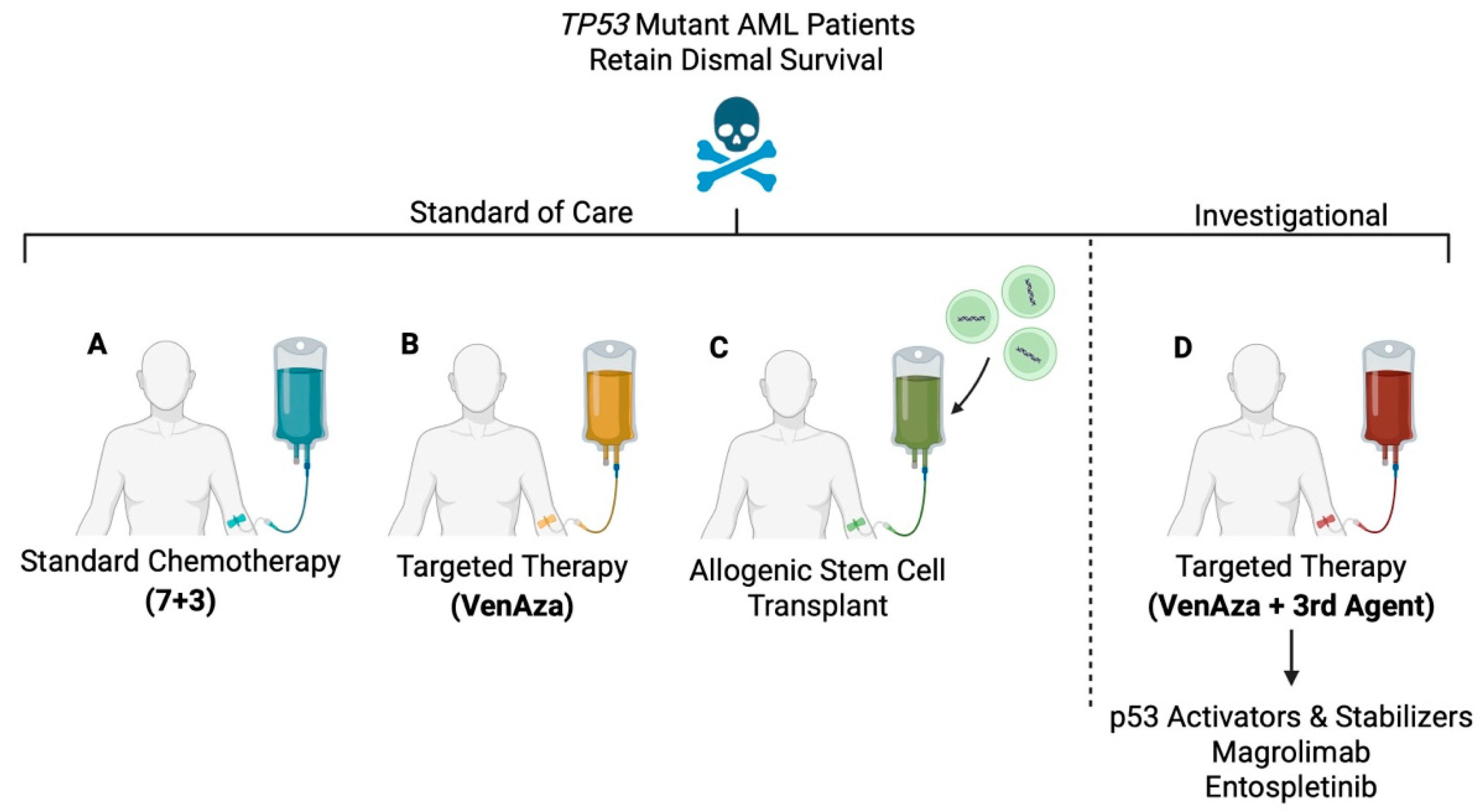

4. Current Therapeutic Landscapes for TP53 Mutant AML

4.1. Induction Chemotherapy (7+3)

4.2. VenAza

4.3. Allogenic Stem Cell Transplant

5. Investigational Therapeutic Landscapes and Challenges for TP53 Mutant AML

5.1. Eprenetapopt

5.2. MDM2 and MDMX Regulators

5.3. Magrolimab

5.4. Entospletinib

6. Mechanisms of Therapy Resistance in TP53 Mutant AML

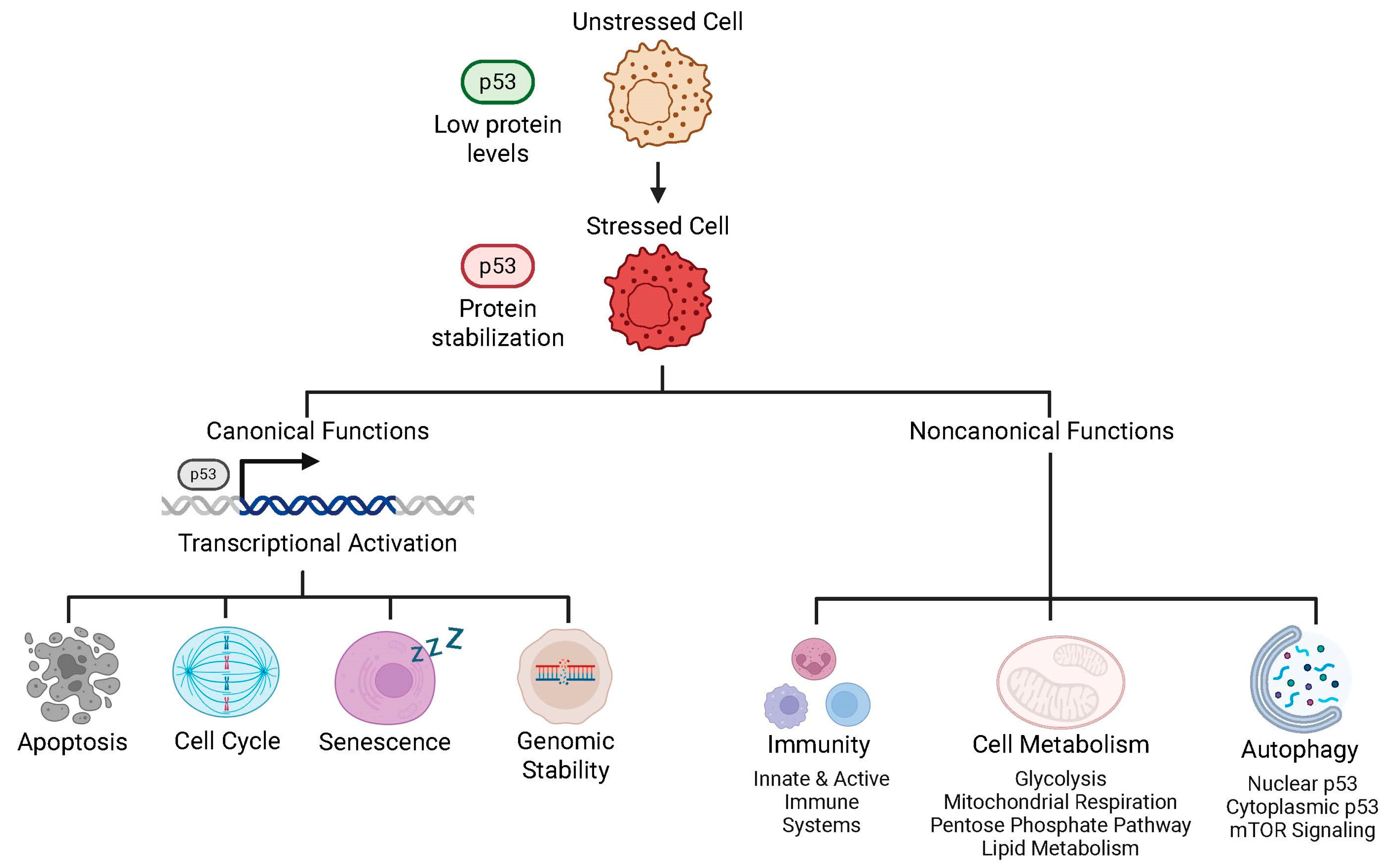

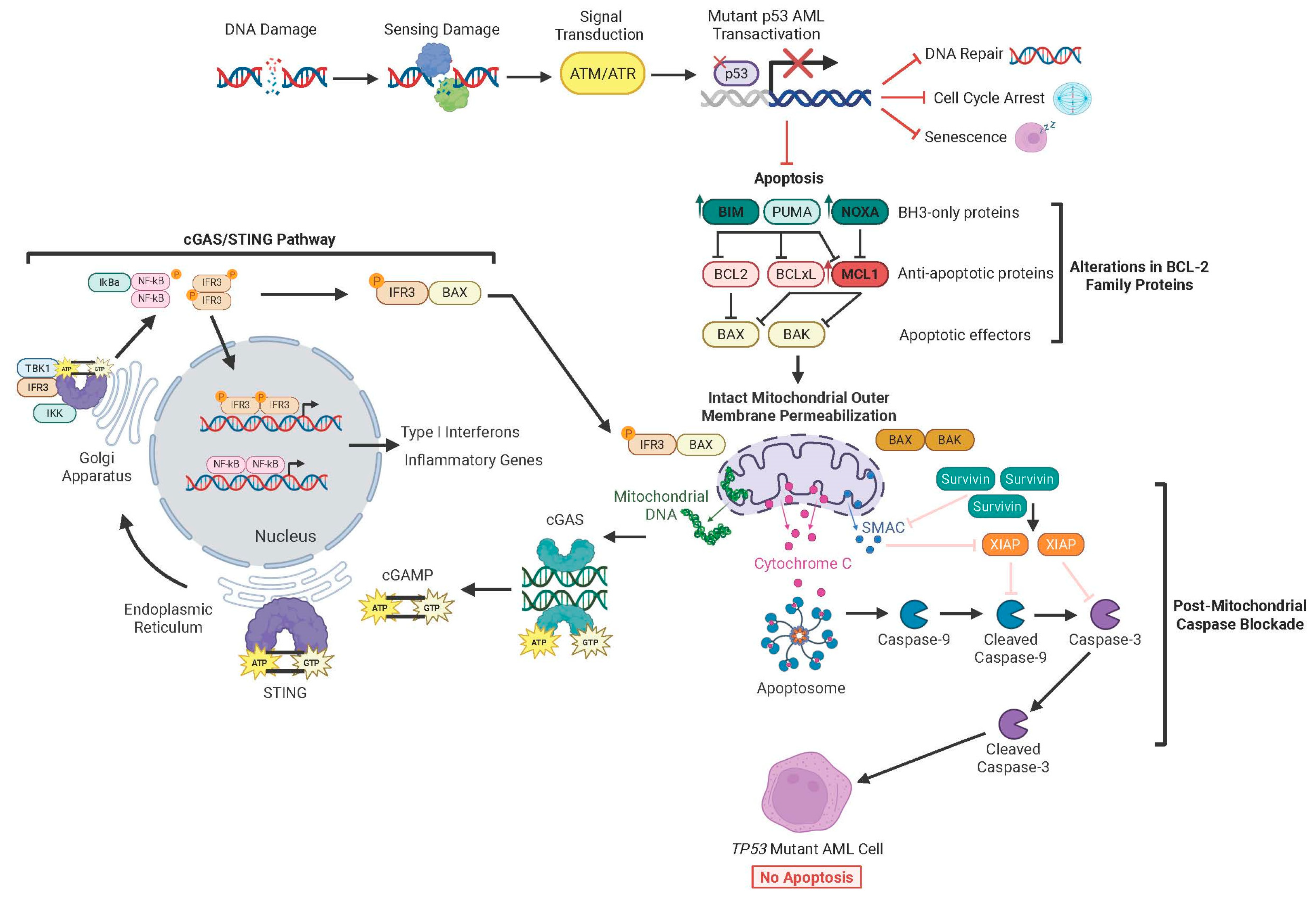

6.1. Functions of Intact p53

6.2. TP53 Mutations Rewire Interactions Between BCL-2 Family Proteins at the Mitochondria

6.3. MOMP Remains Functional Despite Alterations in BCL-2 Family Proteins

6.4. cGAS/STING Signaling Triggers MOMP

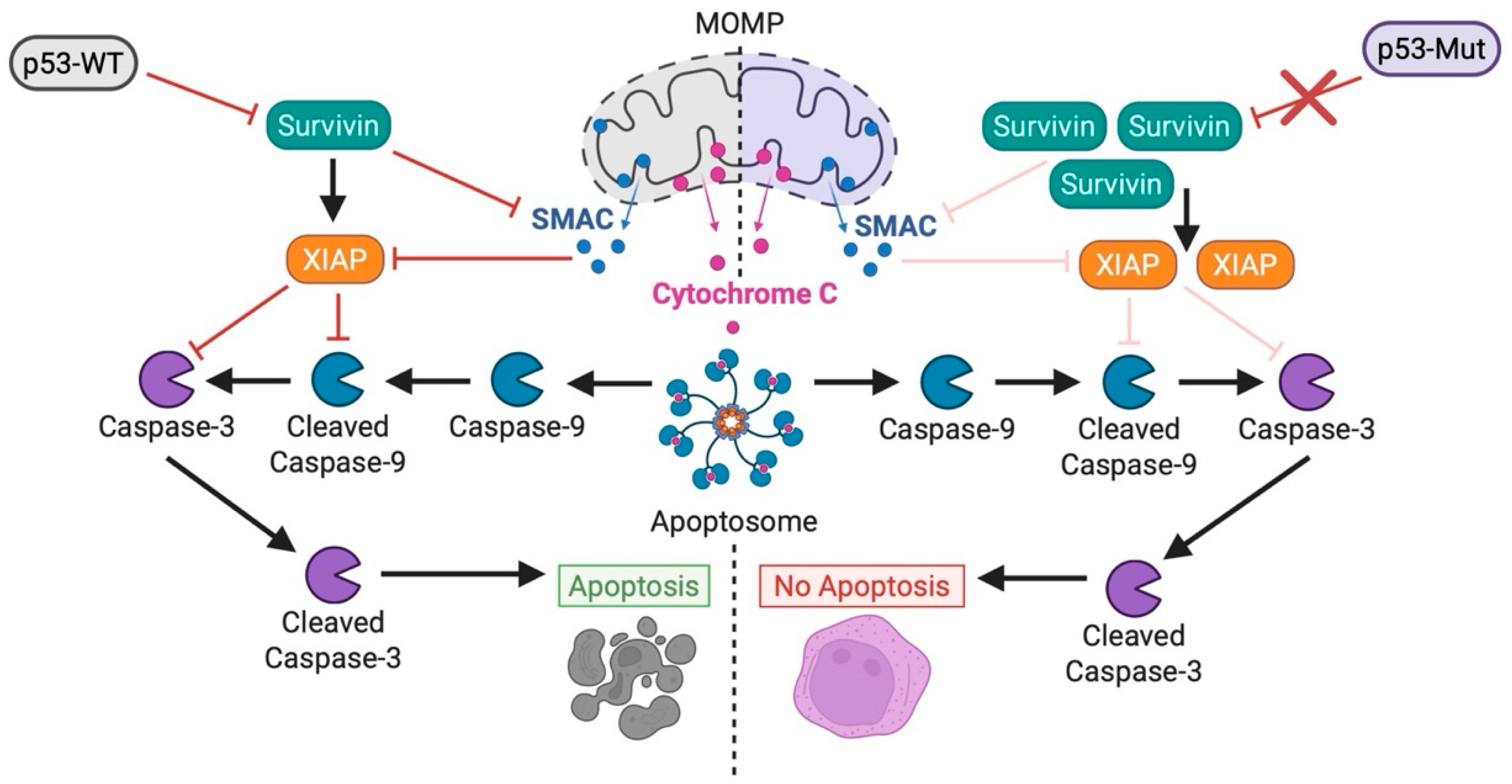

6.5. Dysregulation in Post-MOMP Caspase Activation Drives Therapy Resistance

6.6. Dysregulation in DNA Damage Response Pathways Affects Chemoresistance

6.7. Impaired Cell Cycle Arrest Promotes Expansion of Cells with Aberrant Genomics

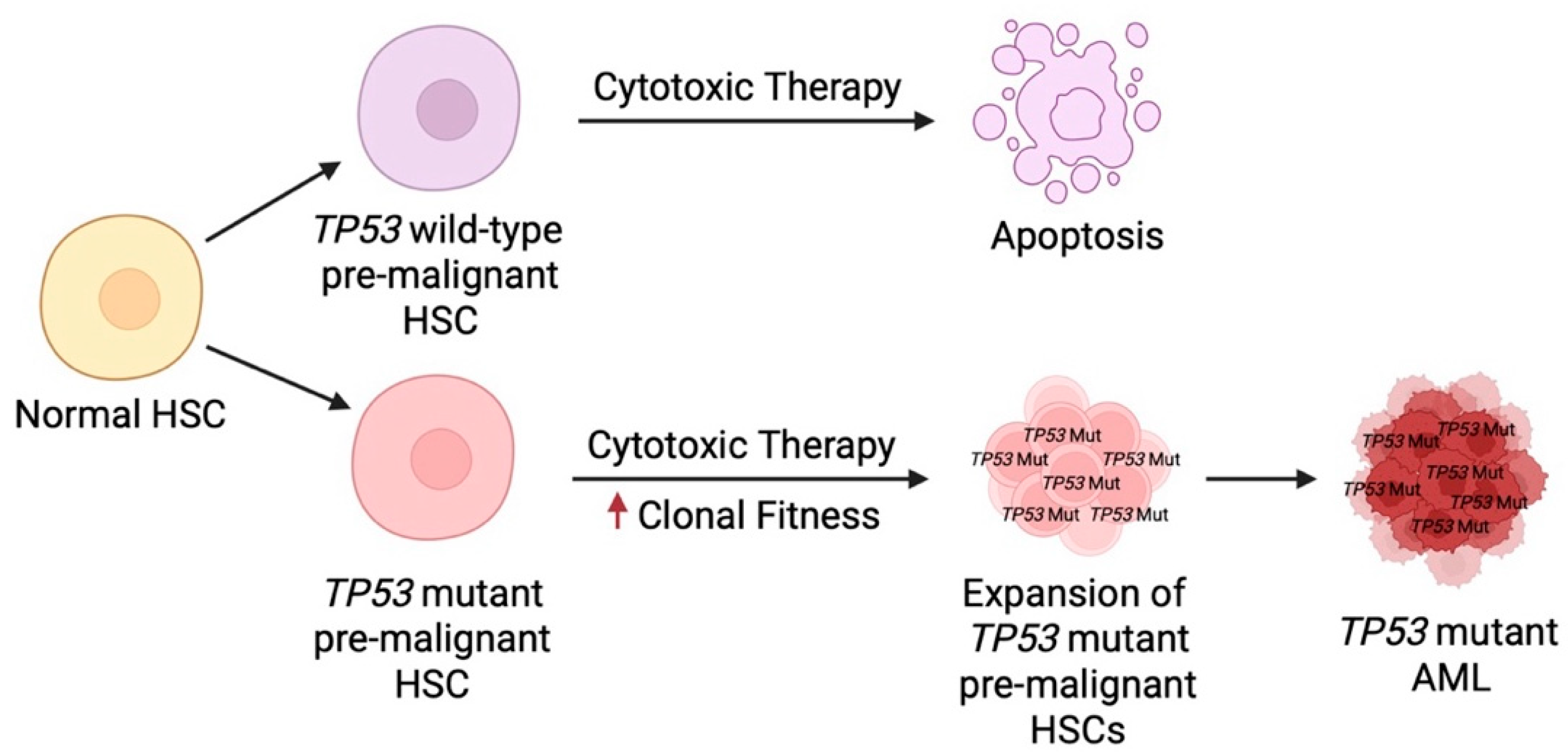

6.8. TP53 Mutant HSCs Demonstrate Abnormal Sub-Clonal Expansion Under Therapeutic Stress

7. Novel Strategies to Overcome Therapy Resistance in TP53 Mutant AML

7.1. BH3 Mimetics

7.2. STING Agonists

7.3. IAP and Survivin Inhibitors

7.4. Rezatapopt

7.5. Mitotic Checkpoint Inhibitors

7.6. Arsenic Trioxide

8. Immunologic and Metabolic Hallmarks of TP53 Mutant AML

8.1. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

8.2. CAR-T Therapy

8.3. Statins

9. Novel Target Discovery by Functional Profiling in TP53 Mutant AML Patients

9.1. Functional Genomic Screening

9.2. Dynamic BH3 Profiling

9.3. Monitoring Clonal Evolution Provides Real-Time Insight into Changing Phenotypes

9.4. Landmark Guidelines and Treatment Consensus for TP53 Mutant AML

10. Future Directions for Targeting TP53 Mutant AML

11. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Döhner, H.; Weisdorf, D.J.; Bloomfield, C.D. Acute Myeloid Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1136–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arber, D.A.; Orazi, A.; Hasserjian, R.; Thiele, J.; Borowitz, M.J.; Le Beau, M.M.; Bloomfield, C.D.; Cazzola, M.; Vardiman, J.W. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood 2016, 127, 2391–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobas, M.A.; Turki, A.T.; Ramiro, A.V.; Hernández-Sánchez, A.; Elicegui, J.M.; González, T.; Melchor, R.A.; Abáigar, M.; Tur, L.; Dall’Olio, D.; et al. Outcomes with intensive treatment for acute myeloid leukemia: An analysis of two decades of data from the HARMONY Alliance. Haematologica 2025, 110, 1126–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemminki, K.; Zitricky, F.; Försti, A.; Kontro, M.; Gjertsen, B.T.; Severinsen, M.T.; Juliusson, G. Age-specific survival in acute myeloid leukemia in the Nordic countries through a half century. Blood Cancer J. 2024, 14, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaemmanuil, E.; Gerstung, M.; Bullinger, L.; Gaidzik, V.I.; Paschka, P.; Roberts, N.D.; Potter, N.E.; Heuser, M.; Thol, F.; Bolli, N.; et al. Genomic Classification and Prognosis in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 2209–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollyea, D.A.; Pratz, K.W.; Wei, A.H.; Pullarkat, V.; Jonas, B.A.; Recher, C.; Babu, S.; Schuh, A.C.; Dail, M.; Sun, Y.; et al. Outcomes in Patients with Poor-Risk Cytogenetics with or without TP53 Mutations Treated with Venetoclax and Azacitidine. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 5272–5279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, A.H.; Strickland, S.A.; Hou, J.-Z.; Fiedler, W.; Lin, T.L.; Walter, R.B.; Enjeti, A.; Tiong, I.S.; Savona, M.; Lee, S.; et al. Venetoclax Combined With Low-Dose Cytarabine for Previously Untreated Patients With Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Results From a Phase Ib/II Study. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 1277–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiNardo, C.D.; Jonas, B.A.; Pullarkat, V.; Thirman, M.J.; Garcia, J.S.; Wei, A.H.; Konopleva, M.; Döhner, H.; Letai, A.; Fenaux, P.; et al. Azacitidine and Venetoclax in Previously Untreated Acute Myeloid Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Liang, Z.; Ji, L.; Liu, W.; Wang, B.; Li, Y.; Ou, J.; Cen, X.; Ren, H.; Wuchty, S.; et al. Comparative outcome and prognostic factor analysis among MDS/AML patients with TP53 mutations, snps, and wild type. Hum. Genom. 2025, 19, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, J.A.; Wang, X.; Fenu, E.M.; Bagg, A.; Lai, C. TP53 in AML and MDS: The new (old) kid on the block. Blood Rev. 2023, 60, 101055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.R.; Kroemer, G. Cytoplasmic functions of the tumour suppressor p53. Nature 2009, 458, 1127–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boettcher, S.; Miller, P.G.; Sharma, R.; McConkey, M.; Leventhal, M.; Krivtsov, A.V.; Giacomelli, A.O.; Wong, W.; Kim, J.; Chao, S.; et al. A dominant-negative effect drives selection of TP53 missense mutations in myeloid malignancies. Science 2019, 365, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petitjean, A.; Achatz, M.I.W.; Borresen-Dale, A.L.; Hainaut, P.; Olivier, M. TP53 mutations in human cancers: Functional selection and impact on cancer prognosis and outcomes. Oncogene 2007, 26, 2157–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimovich, B.; Merle, N.; Neumann, M.; Elmshäuser, S.; Nist, A.; Mernberger, M.; Kazdal, D.; Stenzinger, A.; Timofeev, O.; Stiewe, T. p53 partial loss-of-function mutations sensitize to chemotherapy. Oncogene 2022, 41, 1011–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, P.A.J.; Vousden, K.H. Mutant p53 in cancer: New functions and therapeutic opportunities. Cancer Cell 2014, 25, 304–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, S.W.; Jeon, H.-Y.; Jin, X.; Kim, E.-J.; Kim, J.-K.; Shin, Y.J.; Lee, Y.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, S.Y.; Seo, S.; et al. TP53 gain-of-function mutation promotes inflammation in glioblastoma. Cell Death Differ. 2019, 26, 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrutia, S.; Wong, T.N.; Link, D.C. A clinical guide to TP53 mutations in myeloid neoplasms. Blood 2025, 146, 2157–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rücker, F.G.; Dolnik, A.; Blätte, T.J.; Teleanu, V.; Ernst, A.; Thol, F.; Heuser, M.; Ganser, A.; Döhner, H.; Döhner, K.; et al. Chromothripsis is linked to TP53 alteration, cell cycle impairment, and dismal outcome in acute myeloid leukemia with complex karyotype. Haematologica 2018, 103, e17–e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abelson, S.; Collord, G.; Ng, S.W.K.; Weissbrod, O.; Mendelson Cohen, N.; Niemeyer, E.; Barda, N.; Zuzarte, P.C.; Heisler, L.; Sundaravadanam, Y.; et al. Prediction of acute myeloid leukaemia risk in healthy individuals. Nature 2018, 559, 400–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamdouh, A.M.; Olesinski, E.A.; Lim, F.Q.; Jasdanwala, S.; Mi, Y.; Lin, N.S.E.; Liang, D.T.E.; Chitkara, N.; Hogdal, L.; Lindsley, R.C.; et al. TP53 mutations drive therapy resistance via post-mitochondrial caspase blockade. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubrey, B.J.; Kelly, G.L.; Janic, A.; Herold, M.J.; Strasser, A. How does p53 induce apoptosis and how does this relate to p53-mediated tumour suppression? Cell Death Differ. 2018, 25, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.N.; Ramsingh, G.; Young, A.L.; Miller, C.A.; Touma, W.; Welch, J.S.; Lamprecht, T.L.; Shen, D.; Hundal, J.; Fulton, R.S.; et al. Role of TP53 mutations in the origin and evolution of therapy-related acute myeloid leukaemia. Nature 2015, 518, 552–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, A.N.; Fersht, A.R. Rescuing the function of mutant p53. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2001, 1, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Burigotto, M.; Ghetti, S.; Vaillant, F.; Tan, T.; Capaldo, B.D.; Palmieri, M.; Hirokawa, Y.; Tai, L.; Simpson, D.S.; et al. Loss-of-Function but Not Gain-of-Function Properties of Mutant TP53 Are Critical for the Proliferation, Survival, and Metastasis of a Broad Range of Cancer Cells. Cancer Discov. 2024, 14, 362–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgione, M.O.; McClure, B.J.; Page, E.C.; Yeung, D.T.; Eadie, L.N.; White, D.L. TP53 loss-of-function mutations reduce sensitivity of acute leukaemia to the curaxin CBL0137. Oncol. Rep. 2022, 47, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieging, K.T.; Mello, S.S.; Attardi, L.D. Unravelling mechanisms of p53-mediated tumour suppression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donehower, L.A.; Soussi, T.; Korkut, A.; Liu, Y.; Schultz, A.; Cardenas, M.; Li, X.; Babur, O.; Hsu, T.-K.; Lichtarge, O.; et al. Integrated Analysis of TP53 Gene and Pathway Alterations in The Cancer Genome Atlas. Cell Rep. 2019, 28, 1370–1384.e5, Erratum in Cell Rep. 2019, 28, 3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S.; Pant, V.; Suh, Y.-A.; Van Pelt, C.S.; Wang, Y.; Valentin-Vega, Y.A.; Post, S.M.; Lozano, G. Spontaneous Tumorigenesis in Mice Overexpressing the p53-Negative Regulator Mdm4. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 7148–7154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moll, U.M.; Wolff, S.; Speidel, D.; Deppert, W. Transcription-independent pro-apoptotic functions of p53. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2005, 17, 631–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marine, J.-C.; Dawson, S.-J.; Dawson, M.A. Non-genetic mechanisms of therapeutic resistance in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2020, 20, 743–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itahana, K.; Mao, H.; Jin, A.; Itahana, Y.; Clegg, H.V.; Lindström, M.S.; Bhat, K.P.; Godfrey, V.L.; Evan, G.I.; Zhang, Y. Targeted Inactivation of Mdm2 RING Finger E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Activity in the Mouse Reveals Mechanistic Insights into p53 Regulation. Cancer Cell 2007, 12, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danovi, D.; Meulmeester, E.; Pasini, D.; Migliorini, D.; Capra, M.; Frenk, R.; de Graaf, P.; Francoz, S.; Gasparini, P.; Gobbi, A.; et al. Amplification of Mdmx (or Mdm4) Directly Contributes to Tumor Formation by Inhibiting p53 Tumor Suppressor Activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 24, 5835–5843, Erratum in Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 39, e00150-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marine, J.-C.; Jochemsen, A.G. MDMX (MDM4), a Promising Target for p53 Reactivation Therapy and Beyond. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2016, 6, a026237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Luo, J.; Brooks, C.L.; Gu, W. Acetylation of p53 Inhibits Its Ubiquitination by Mdm2. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 50607–50611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, W.; Roeder, R.G. Activation of p53 sequence-specific DNA binding by acetylation of the p53 C-terminal domain. Cell 1997, 90, 595–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuikov, S.; Kurash, J.K.; Wilson, J.R.; Xiao, B.; Justin, N.; Ivanov, G.S.; McKinney, K.; Tempst, P.; Prives, C.; Gamblin, S.J.; et al. Regulation of p53 activity through lysine methylation. Nature 2004, 432, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, G.S.; Ivanova, T.; Kurash, J.; Ivanov, A.; Chuikov, S.; Gizatullin, F.; Herrera-Medina, E.M.; Rauscher, F.; Reinberg, D.; Barlev, N.A. Methylation-acetylation interplay activates p53 in response to DNA damage. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007, 27, 6756–6769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travé, G.; Zanier, K. HPV-mediated inactivation of tumor suppressor p53. Cell Cycle 2016, 15, 2231–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbelstein, M.; Roth, J. The large T antigen of simian virus 40 binds and inactivates p53 but not p73. J. Gen. Virol. 1998, 79 Pt 12, 3079–3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, M.E.D.; Berk, A.J. Adenovirus E1B 55K Represses p53 Activation In Vitro. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 3146–3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, H.A.; Lin, C.C.; Chou, W.C.; Liu, C.Y.; Chen, C.Y.; Tang, J.L.; Lai, Y.J.; Tseng, M.H.; Huang, C.F.; Chiang, Y.C.; et al. Integration of cytogenetic and molecular alterations in risk stratification of 318 patients with de novo non-M3 acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2014, 28, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Abro, B.; Campbell, A.; Ding, Y. TP53 mutations in myeloid neoplasms: Implications for accurate laboratory detection, diagnosis, and treatment. Lab. Med. 2024, 55, 686–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncavage, E.J.; Bagg, A.; Hasserjian, R.P.; DiNardo, C.D.; Godley, L.A.; Iacobucci, I.; Jaiswal, S.; Malcovati, L.; Vannucchi, A.M.; Patel, K.P.; et al. Genomic profiling for clinical decision making in myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood 2022, 140, 2228–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Ven, M.; Simons, M.J.H.G.; Koffijberg, H.; Joore, M.A.; IJzerman, M.J.; Retèl, V.P.; van Harten, W.H. Whole genome sequencing in oncology: Using scenario drafting to explore future developments. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaic, A.; Motofelea, N.; Hoinoiu, T.; Motofelea, A.C.; Leancu, I.C.; Stan, E.; Gheorghe, S.R.; Dutu, A.G.; Crintea, A. Next-Generation Sequencing: A Review of Its Transformative Impact on Cancer Diagnosis, Treatment, and Resistance Management. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atli, E.I.; Gurkan, H.; Atli, E.; Kirkizlar, H.O.; Yalcintepe, S.; Demir, S.; Demirci, U.; Eker, D.; Mail, C.; Kalkan, R.; et al. The Importance of Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing Usage in Cytogenetically Normal Myeloid Malignancies. Mediterr. J. Hematol. Infect. Dis. 2021, 13, e2021013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, P.-H.; Li, H.-Y.; Fan, S.-C.; Yuan, T.-H.; Chen, M.; Hsu, Y.-H.; Yang, Y.-H.; Li, L.-Y.; Yeh, S.-P.; Bai, L.-Y.; et al. A targeted next-generation sequencing in the molecular risk stratification of adult acute myeloid leukemia: Implications for clinical practice. Cancer Med. 2017, 6, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rücker, F.G.; Schlenk, R.F.; Bullinger, L.; Kayser, S.; Teleanu, V.; Kett, H.; Habdank, M.; Kugler, C.-M.; Holzmann, K.; Gaidzik, V.I.; et al. TP53 alterations in acute myeloid leukemia with complex karyotype correlate with specific copy number alterations, monosomal karyotype, and dismal outcome. Blood 2012, 119, 2114–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.N.; Link, D.C. Are TP53 mutations all alike? Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program 2024, 2024, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahaj, W.; Kewan, T.; Gurnari, C.; Durmaz, A.; Ponvilawan, B.; Pandit, I.; Kubota, Y.; Ogbue, O.D.; Zawit, M.; Madanat, Y.; et al. Novel scheme for defining the clinical implications of TP53 mutations in myeloid neoplasia. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2023, 16, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, E.; Nannya, Y.; Hasserjian, R.P.; Devlin, S.M.; Tuechler, H.; Medina-Martinez, J.S.; Yoshizato, T.; Shiozawa, Y.; Saiki, R.; Malcovati, L.; et al. Implications of TP53 allelic state for genome stability, clinical presentation and outcomes in myelodysplastic syndromes. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 1549–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arber, D.A.; Orazi, A.; Hasserjian, R.P.; Borowitz, M.J.; Calvo, K.R.; Kvasnicka, H.-M.; Wang, S.A.; Bagg, A.; Barbui, T.; Branford, S.; et al. International Consensus Classification of Myeloid Neoplasms and Acute Leukemias: Integrating morphologic, clinical, and genomic data. Blood 2022, 140, 1200–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feurstein, S.; Rücker, F.G.; Bullinger, L.; Hofmann, W.; Manukjan, G.; Göhring, G.; Lehmann, U.; Heuser, M.; Ganser, A.; Döhner, K.; et al. Haploinsufficiency of ETV6 and CDKN1B in patients with acute myeloid leukemia and complex karyotype. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsley, R.C.; Saber, W.; Mar, B.G.; Redd, R.; Wang, T.; Haagenson, M.D.; Grauman, P.V.; Hu, Z.-H.; Spellman, S.R.; Lee, S.J.; et al. Prognostic Mutations in Myelodysplastic Syndrome after Stem-Cell Transplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 536–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, G.; Han, X. The Prognostic Value of TP53 Mutations in Adult Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Meta-Analysis. Transfus. Med. Hemother. 2022, 50, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.; Amin, M.K.; Daver, N.G.; Shah, M.V.; Hiwase, D.; Arber, D.A.; Kharfan-Dabaja, M.A.; Badar, T. What have we learned about TP53-mutated acute myeloid leukemia? Blood Cancer J. 2024, 14, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.V.; Hung, K.; Baranwal, A.; Kutyna, M.M.; Al-Kali, A.; Toop, C.; Greipp, P.; Brown, A.; Shah, S.; Khanna, S.; et al. Evidence-based risk stratification of myeloid neoplasms harboring TP53 mutations. Blood Adv. 2025, 9, 3370–3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Short, N.J.; Montalban-Bravo, G.; Hwang, H.; Ning, J.; Franquiz, M.J.; Kanagal-Shamanna, R.; Patel, K.P.; DiNardo, C.D.; Ravandi, F.; Garcia-Manero, G.; et al. Prognostic and therapeutic impacts of mutant TP53 variant allelic frequency in newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Adv. 2020, 4, 5681–5689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawacka, J.E. p53 biology and reactivation for improved therapy in MDS and AML. Biomark. Res. 2024, 12, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stengel, A.; Kern, W.; Haferlach, T.; Meggendorfer, M.; Fasan, A.; Haferlach, C. The impact of TP53 mutations and TP53 deletions on survival varies between AML, ALL, MDS and CLL: An analysis of 3307 cases. Leukemia 2017, 31, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemanova, Z.; Michalova, K.; Svobodova, K.; Brezinova, J.; Lhotska, H.; Lizcova, L.; Sarova, I.; Izakova, S.; Hodanova, L.; Vesela, D.; et al. Chromothripsis in High-Risk Myelodysplastic Syndromes: Incidence, Genetic Features, Clinical Implications, and Impact on Survival of Patients Treated with Azacytidine (Data from Czech MDS Group). Blood 2018, 132 (Suppl. S1), 1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, J.S. Patterns of mutations in TP53 mutated AML. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Haematol. 2018, 31, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.-Y. TP53 Mutation in Acute Myeloid Leukemia: An Old Foe Revisited. Cancers 2023, 15, 4816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montalban-Bravo, G.; Kanagal-Shamanna, R.; Benton, C.B.; Class, C.A.; Chien, K.S.; Sasaki, K.; Naqvi, K.; Alvarado, Y.; Kadia, T.M.; Ravandi, F.; et al. Genomic context and TP53 allele frequency define clinical outcomes in TP53-mutated myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood Adv. 2020, 4, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, O.K.; Siddon, A.; Madanat, Y.F.; Gagan, J.; Arber, D.A.; Dal Cin, P.; Narayanan, D.; Ouseph, M.M.; Kurzer, J.H.; Hasserjian, R.P. TP53 mutation defines a unique subgroup within complex karyotype de novo and therapy-related MDS/AML. Blood Adv. 2022, 6, 2847–2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cluzeau, T.; Loschi, M.; Fenaux, P.; Komrokji, R.; Sallman, D.A. Personalized Medicine for TP53 Mutated Myelodysplastic Syndromes and Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bănescu, C.; Tripon, F.; Muntean, C. The Genetic Landscape of Myelodysplastic Neoplasm Progression to Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambhekar, A.; Ackerman, E.E.; Alpay, B.A.; Lahav, G.; Lovitch, S.B. Comparison of TP53 Mutations in Myelodysplasia and Acute Leukemia Suggests Divergent Roles in Initiation and Progression. medRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aedma, S.K.; Kasi, A. Li-Fraumeni Syndrome. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532286/ (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Simon, L.; Spinella, J.-F.; Yao, C.-Y.; Lavallée, V.-P.; Boivin, I.; Boucher, G.; Audemard, E.; Bordeleau, M.-E.; Lemieux, S.; Hébert, J.; et al. High frequency of germline RUNX1 mutations in patients with RUNX1-mutated AML. Blood 2020, 135, 1882–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellissimo, D.C.; Speck, N.A. RUNX1 Mutations in Inherited and Sporadic Leukemia. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2017, 5, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, A.P.; Sampaio, E.P.; Khan, J.; Calvo, K.R.; Lemieux, J.E.; Patel, S.Y.; Frucht, D.M.; Vinh, D.C.; Auth, R.D.; Freeman, A.F.; et al. Mutations in GATA2 are associated with the autosomal dominant and sporadic monocytopenia and mycobacterial infection (MonoMAC) syndrome. Blood 2011, 118, 2653–2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, R.V.; Arnold, D.E. GATA2 Deficiency: Predisposition to Myeloid Malignancy and Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Curr. Hematol. Malig. Rep. 2023, 18, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bannon, S.A.; DiNardo, C.D.; Bannon, S.A.; DiNardo, C.D. Hereditary Predispositions to Myelodysplastic Syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sébert, M.; Passet, M.; Raimbault, A.; Rahmé, R.; Raffoux, E.; Sicre de Fontbrune, F.; Cerrano, M.; Quentin, S.; Vasquez, N.; Da Costa, M.; et al. Germline DDX41 mutations define a significant entity within adult MDS/AML patients. Blood 2019, 134, 1441–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arai, H.; Matsui, H.; Chi, S.; Utsu, Y.; Masuda, S.; Aotsuka, N.; Minami, Y. Germline Variants and Characteristic Features of Hereditary Hematological Malignancy Syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feurstein, S.; Godley, L.A. Germline ETV6 mutations and predisposition to hematological malignancies. Int. J. Hematol. 2017, 106, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trottier, A.M.; Feurstein, S.; Godley, L.A. Germline predisposition to myeloid neoplasms: Characteristics and management of high versus variable penetrance disorders. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Haematol. 2024, 37, 101537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Eladl, E.; Zarif, M.; Capo-Chichi, J.-M.; Schuh, A.; Atenafu, E.; Minden, M.; Chang, H. Molecular characterization of AML-MRC reveals TP53 mutation as an adverse prognostic factor irrespective of MRC-defining criteria, TP53 allelic state, or TP53 variant allele frequency. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 6511–6522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colmenares, R.; Alvarez, N.; Barragan, E.; Boluda, B.; Larrayoz, M.J.; Chillon, M.C.; Soria-Saldise, E.; Bilbao, C.; Sanchez-Garcia, J.; Bernal, T.; et al. Prognostic relevance of variant allele frequency for treatment outcomes in patients with acute myeloid leukemia: A study by the Spanish PETHEMA registry. Haematologica 2025, 110, 1623–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, K.; Kanagal-Shamanna, R.; Montalban-Bravo, G.; Assi, R.; Jabbour, E.; Ravandi, F.; Kadia, T.; Pierce, S.; Takahashi, K.; Nogueras Gonzalez, G.; et al. Impact of the variant allele frequency of ASXL1, DNMT3A, JAK2, TET2, TP53, and NPM1 on the outcomes of patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer 2020, 126, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, E.; Sill, H. The TP53 Pro72Arg SNP in de novo acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica 2017, 102, e214–e215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGraw, K.L.; Cluzeau, T.; Sallman, D.A.; Basiorka, A.A.; Irvine, B.A.; Zhang, L.; Epling-Burnette, P.K.; Rollison, D.E.; Mallo, M.; Sokol, L.; et al. TP53 and MDM2 single nucleotide polymorphisms influence survival in non-del(5q) myelodysplastic syndromes. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 34437–34445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Döhner, H.; Wei, A.H.; Appelbaum, F.R.; Craddock, C.; DiNardo, C.D.; Dombret, H.; Ebert, B.L.; Fenaux, P.; Godley, L.A.; Hasserjian, R.P.; et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2022 recommendations from an international expert panel on behalf of the ELN. Blood 2022, 140, 1345–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estey, E.; Döhner, H. Acute myeloid leukaemia. Lancet 2006, 368, 1894–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daver, N.; Wei, A.H.; Pollyea, D.A.; Fathi, A.T.; Vyas, P.; DiNardo, C.D. New directions for emerging therapies in acute myeloid leukemia: The next chapter. Blood Cancer J. 2020, 10, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumransub, N. TP53-Mutated Acute Myeloid Leukemia Patients Treated with Intensive Therapies Have Superior Outcomes: A Single Institution, Retrospective Study; ASH: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; Available online: https://ash.confex.com/ash/2023/webprogram/Paper177757.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Bhatt, S.; Pioso, M.S.; Olesinski, E.A.; Yilma, B.; Ryan, J.A.; Mashaka, T.; Leutz, B.; Adamia, S.; Zhu, H.; Kuang, Y.; et al. Reduced Mitochondrial Apoptotic Priming Drives Resistance to BH3 Mimetics in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer Cell 2020, 38, 872–890.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, R.; Hogdal, L.J.; Benito, J.M.; Bucci, D.; Han, L.; Borthakur, G.; Cortes, J.; DeAngelo, D.J.; Debose, L.; Mu, H.; et al. Selective BCL-2 inhibition by ABT-199 causes on-target cell death in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Discov. 2014, 4, 362–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souers, A.J.; Leverson, J.D.; Boghaert, E.R.; Ackler, S.L.; Catron, N.D.; Chen, J.; Dayton, B.D.; Ding, H.; Enschede, S.H.; Fairbrother, W.J.; et al. ABT-199, a potent and selective BCL-2 inhibitor, achieves antitumor activity while sparing platelets. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratz, K.W.; Jonas, B.A.; Pullarkat, V.; Thirman, M.J.; Garcia, J.S.; Döhner, H.; Récher, C.; Fiedler, W.; Yamamoto, K.; Wang, J.; et al. Long-term follow-up of VIALE-A: Venetoclax and azacitidine in chemotherapy-ineligible untreated acute myeloid leukemia. Am. J. Hematol. 2024, 99, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konopleva, M.; Letai, A. BCL-2 inhibition in AML: An unexpected bonus? Blood 2018, 132, 1007–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiNardo, C.D.; Pratz, K.; Pullarkat, V.; Jonas, B.A.; Arellano, M.; Becker, P.S.; Frankfurt, O.; Konopleva, M.; Wei, A.H.; Kantarjian, H.M.; et al. Venetoclax combined with decitabine or azacitidine in treatment-naive, elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2019, 133, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Maiti, A.; Loghavi, S.; Pourebrahim, R.; Kadia, T.M.; Rausch, C.R.; Furudate, K.; Daver, N.G.; Alvarado, Y.; Ohanian, M.; et al. Outcomes of TP53-mutant acute myeloid leukemia with decitabine and venetoclax. Cancer 2021, 127, 3772–3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devillier, R.; Forcade, E.; Garnier, A.; Guenounou, S.; Thepot, S.; Guillerm, G.; Ceballos, P.; Hicheri, Y.; Dumas, P.-Y.; Peterlin, P.; et al. In-depth time-dependent analysis of the benefit of allo-HSCT for elderly patients with CR1 AML: A FILO study. Blood Adv. 2022, 6, 1804–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederwieser, D.; Hasenclever, D.; Berdel, W.E.; Biemond, B.J.; Al-Ali, H.; Chalandon, Y.; van Gelder, M.; Junghanß, C.; Gahrton, G.; Hänel, M.; et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation for older acute myeloid leukemia patients in first complete remission: Results of a randomized phase III study. Haematologica 2025, 110, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatari, M.; Kasaeian, A.; Mousavian, A.-H.; Oskouie, I.M.; Yazdani, A.; Mousavi, S.A.; Zeraati, H.; Yaseri, M. Prognostic factors for survival after allogeneic transplantation in acute myeloid leukemia in Iran using censored quantile regression model. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozaffari Jovein, M.; Ihorst, G.; Duque-Afonso, J.; Wäsch, R.; Bertz, H.; Wehr, C.; Duyster, J.; Zeiser, R.; Finke, J.; Scherer, F. Long-term follow-up of patients with acute myeloid leukemia undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation after primary induction failure. Blood Cancer J. 2023, 13, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baranwal, A.; Langer, K.J.; Gannamani, V.; Rud, D.; Cibich, A.; Saygin, C.; Nawas, M.; Badar, T.; Kharfan-Dabaja, M.A.; Ayala, E.; et al. Factors associated with survival after allogeneic transplantation for myeloid neoplasms harboring TP53 mutations. Blood Adv. 2025, 9, 3395–3407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badar, T.; Atallah, E.; Shallis, R.; Saliba, A.N.; Patel, A.; Bewersdorf, J.P.; Grenet, J.; Stahl, M.; Duvall, A.; Burkart, M.; et al. Survival of TP53-mutated acute myeloid leukemia patients receiving allogeneic stem cell transplantation after first induction or salvage therapy: Results from the Consortium on Myeloid Malignancies and Neoplastic Diseases (COMMAND). Leukemia 2023, 37, 799–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahzad, M.; Iqbal, Q.; Tariq, E.; Ammad-Ud-Din, M.; Butt, A.; Mushtaq, A.H.; Ali, F.; Chaudhary, S.G.; Anwar, I.; Gonzalez-Lugo, J.D.; et al. Outcomes with allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in TP53-mutated myelodysplastic syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2024, 196, 104310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, H.-Y.; Lee, H.-Y. Molecular targeted therapy for anticancer treatment. Exp. Mol. Med. 2022, 54, 1670–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, J.P.; Gönen, M.; Figueroa, M.E.; Fernandez, H.; Sun, Z.; Racevskis, J.; Vlierberghe, P.V.; Dolgalev, I.; Thomas, S.; Aminova, O.; et al. Prognostic Relevance of Integrated Genetic Profiling in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 1079–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döhner, H.; Estey, E.H.; Amadori, S.; Appelbaum, F.R.; Büchner, T.; Burnett, A.K.; Dombret, H.; Fenaux, P.; Grimwade, D.; Larson, R.A.; et al. Diagnosis and management of acute myeloid leukemia in adults: Recommendations from an international expert panel, on behalf of the European LeukemiaNet. Blood 2010, 115, 453–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallman, D.A.; DeZern, A.E.; Garcia-Manero, G.; Steensma, D.P.; Roboz, G.J.; Sekeres, M.A.; Cluzeau, T.; Sweet, K.L.; McLemore, A.; McGraw, K.L.; et al. Eprenetapopt (APR-246) and Azacitidine in TP53-Mutant Myelodysplastic Syndromes. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 1584–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprea Therapeutics Announces Removal of FDA Clinical Hold on Eprenetapopt in Lymphoid Malignancies|Aprea Therapeutics. Available online: https://ir.aprea.com/news-releases/news-release-details/aprea-therapeutics-announces-removal-fda-clinical-hold/ (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Yan, H.; Zou, T.; Tuo, Q.; Xu, S.; Li, H.; Belaidi, A.A.; Lei, P. Ferroptosis: Mechanisms and links with diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, J.B.J.; Mohd, A.A.; Kareem, B.A.; Herrada, S.J.; Ruck, L.; Herrada, J. AML-587: Systematic Review of Ferroptosis-Inducing Therapies in TP53-Mutant Acute Myeloid Leukemia and Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2025, 25, S442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujihara, K.M.; Zhang, B.Z.; Jackson, T.D.; Ogunkola, M.O.; Nijagal, B.; Milne, J.V.; Sallman, D.A.; Ang, C.-S.; Nikolic, I.; Kearney, C.J.; et al. Eprenetapopt triggers ferroptosis, inhibits NFS1 cysteine desulfurase, and synergizes with serine and glycine dietary restriction. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabm9427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerlavais, V.; Sawyer, T.K.; Carvajal, L.; Chang, Y.S.; Graves, B.; Ren, J.-G.; Sutton, D.; Olson, K.A.; Packman, K.; Darlak, K.; et al. Discovery of Sulanemadlin (ALRN-6924), the First Cell-Permeating, Stabilized α-Helical Peptide in Clinical Development. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 9401–9417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassin, O.; Oren, M. Drugging p53 in cancer: One protein, many targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2023, 22, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haaland, I.; Opsahl, J.A.; Berven, F.S.; Reikvam, H.; Fredly, H.K.; Haugse, R.; Thiede, B.; McCormack, E.; Lain, S.; Bruserud, Ø.; et al. Molecular mechanisms of nutlin-3 involve acetylation of p53, histones and heat shock proteins in acute myeloid leukemia. Mol. Cancer 2014, 13, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zauli, G.; Celeghini, C.; Melloni, E.; Voltan, R.; Ongari, M.; Tiribelli, M.; di Iasio, M.G.; Lanza, F.; Secchiero, P. The sorafenib plus nutlin-3 combination promotes synergistic cytotoxicity in acute myeloid leukemic cells irrespectively of FLT3 and p53 status. Haematologica 2012, 97, 1722–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelis, M.; Schneider, C.; Rothweiler, F.; Rothenburger, T.; Mernberger, M.; Nist, A.; von Deimling, A.; Speidel, D.; Stiewe, T.; Cinatl, J. TP53 mutations and drug sensitivity in acute myeloid leukaemia cells with acquired MDM2 inhibitor resistance. bioRxiv 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreeff, M.; Kelly, K.R.; Yee, K.; Assouline, S.; Strair, R.; Popplewell, L.; Bowen, D.; Martinelli, G.; Drummond, M.W.; Vyas, P.; et al. Results of the Phase I Trial of RG7112, a Small-Molecule MDM2 Antagonist in Leukemia. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 868–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warso, M.A.; Richards, J.M.; Mehta, D.; Christov, K.; Schaeffer, C.; Rae Bressler, L.; Yamada, T.; Majumdar, D.; Kennedy, S.A.; Beattie, C.W.; et al. A first-in-class, first-in-human, phase I trial of p28, a non-HDM2-mediated peptide inhibitor of p53 ubiquitination in patients with advanced solid tumours. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 108, 1061–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lulla, R.R.; Goldman, S.; Yamada, T.; Beattie, C.W.; Bressler, L.; Pacini, M.; Pollack, I.F.; Fisher, P.G.; Packer, R.J.; Dunkel, I.J.; et al. Phase I trial of p28 (NSC745104), a non-HDM2-mediated peptide inhibitor of p53 ubiquitination in pediatric patients with recurrent or progressive central nervous system tumors: A Pediatric Brain Tumor Consortium Study. Neuro-Oncol. 2016, 18, 1319–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swoboda, D.M.; Sallman, D.A. The promise of macrophage directed checkpoint inhibitors in myeloid malignancies. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Haematol. 2020, 33, 101221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daver, N.G.; Vyas, P.; Kambhampati, S.; Al Malki, M.M.; Larson, R.A.; Asch, A.S.; Mannis, G.; Chai-Ho, W.; Tanaka, T.N.; Bradley, T.J.; et al. Tolerability and Efficacy of the Anticluster of Differentiation 47 Antibody Magrolimab Combined With Azacitidine in Patients With Previously Untreated AML: Phase Ib Results. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 4893–4904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidner, J.F.; Sallman, D.A.; Récher, C.; Daver, N.G.; Leung, A.Y.H.; Hiwase, D.K.; Subklewe, M.; Pabst, T.; Montesinos, P.; Larson, R.A.; et al. Magrolimab plus azacitidine vs physician’s choice for untreated TP53-mutated acute myeloid leukemia: The ENHANCE-2 study. Blood 2025, 146, 590–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio, J.C.; Smith, P.; Knorr, D.A.; Ravetch, J.V. The Antitumor Activities of Anti-CD47 Antibodies Require Fc-FcγR interactions. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daver, N.; Senapati, J.; Kantarjian, H.M.; Wang, B.; Reville, P.K.; Loghavi, S.; Yilmaz, M.; DiNardo, C.D.; Kadia, T.M.; Yassouf, M.Y.; et al. Azacitidine, Venetoclax, and Magrolimab in Newly Diagnosed and Relapsed Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Phase Ib/II Study and Correlative Analysis. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 31, 2386–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, J.; Vallurupalli, M.; Noel, S.; Schor, G.; Liu, Y.; Nobrega, C.; Perera, J.J.; Wrona, E.; Hu, M.; Lin, Y.; et al. Sialylated CD43 is a glyco-immune checkpoint for macrophage phagocytosis. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, V.H.; Ruppert, A.S.; Mims, A.S.; Borate, U.; Stein, E.M.; Baer, M.R.; Stock, W.; Kovacsovics, T.; Blum, W.G.; Arellano, M.L.; et al. Entospletinib (ENTO) and Decitabine (DEC) Combination Therapy in Older Newly Diagnosed (ND) Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) Patients with Mutant TP53 or Complex Karyotype Is Associated with Poor Response and Survival: A Phase 2 Sub-Study of the Beat AML Master Trial. Blood 2021, 138 (Suppl. S1), 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, V.H.; Ruppert, A.S.; Mims, A.S.; Borate, U.; Stein, E.M.; Baer, M.R.; Stock, W.; Kovacsovics, T.; Blum, W.; Arellano, M.L.; et al. Entospletinib with decitabine in acute myeloid leukemia with mutant TP53 or complex karyotype: A phase 2 substudy of the Beat AML Master Trial. Cancer 2023, 129, 2308–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartaula-Brevik, S.; Lindstad Brattås, M.K.; Tvedt, T.H.A.; Reikvam, H.; Bruserud, Ø. Splenic tyrosine kinase (SYK) inhibitors and their possible use in acute myeloid leukemia. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2018, 27, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnevale, J.; Ross, L.; Puissant, A.; Banerji, V.; Stone, R.M.; DeAngelo, D.J.; Ross, K.N.; Stegmaier, K. SYK Regulates mTOR Signaling in AML. Leukemia 2013, 27, 2118–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Gu, W. Dual Roles of MDM2 in the Regulation of p53. Genes Cancer 2012, 3, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeland, K. Cell cycle regulation: p53-p21-RB signaling. Cell Death Differ. 2022, 29, 946–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlsen, L.; Zhang, S.; Tian, X.; De La Cruz, A.; George, A.; Arnoff, T.E.; El-Deiry, W.S. The role of p53 in anti-tumor immunity and response to immunotherapy. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2023, 10, 1148389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Guo, G. Immunomodulatory Function of the Tumor Suppressor p53 in Host Immune Response and the Tumor Microenvironment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Mehew, J.W.; Heckman, C.A.; Arcinas, M.; Boxer, L.M. Negative regulation of bcl-2 expression by p53 in hematopoietic cells. Oncogene 2001, 20, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Wang, Z.; Kinzler, K.W.; Vogelstein, B.; Zhang, L. PUMA mediates the apoptotic response to p53 in colorectal cancer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 1931–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oda, E.; Ohki, R.; Murasawa, H.; Nemoto, J.; Shibue, T.; Yamashita, T.; Tokino, T.; Taniguchi, T.; Tanaka, N. Noxa, a BH3-only member of the Bcl-2 family and candidate mediator of p53-induced apoptosis. Science 2000, 288, 1053–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyashita, T.; Harigai, M.; Hanada, M.; Reed, J.C. Identification of a p53-dependent negative response element in the bcl-2 gene. Cancer Res. 1994, 54, 3131–3135. [Google Scholar]

- Marchenko, N.D.; Wolff, S.; Erster, S.; Becker, K.; Moll, U.M. Monoubiquitylation promotes mitochondrial p53 translocation. EMBO J. 2007, 26, 923–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaseva, A.V.; Moll, U.M. The mitochondrial p53 pathway. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1787, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erster, S.; Mihara, M.; Kim, R.H.; Petrenko, O.; Moll, U.M. In Vivo Mitochondrial p53 Translocation Triggers a Rapid First Wave of Cell Death in Response to DNA Damage That Can Precede p53 Target Gene Activation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 24, 6728–6741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihara, M.; Erster, S.; Zaika, A.; Petrenko, O.; Chittenden, T.; Pancoska, P.; Moll, U.M. p53 Has a Direct Apoptogenic Role at the Mitochondria. Mol. Cell 2003, 11, 577–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leu, J.I.-J.; Dumont, P.; Hafey, M.; Murphy, M.E.; George, D.L. Mitochondrial p53 activates Bak and causes disruption of a Bak-Mcl1 complex. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004, 6, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipuk, J.E.; Kuwana, T.; Bouchier-Hayes, L.; Droin, N.M.; Newmeyer, D.D.; Schuler, M.; Green, D.R. Direct activation of Bax by p53 mediates mitochondrial membrane permeabilization and apoptosis. Science 2004, 303, 1010–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipuk, J.E.; Bouchier-Hayes, L.; Kuwana, T.; Newmeyer, D.D.; Green, D.R. PUMA couples the nuclear and cytoplasmic proapoptotic function of p53. Science 2005, 309, 1732–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.F.; Kelly, G.L.; Strasser, A. Of the many cellular responses activated by TP53, which ones are critical for tumour suppression? Cell Death Differ. 2022, 29, 961–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond, E.M.; Giaccia, A.J. The role of p53 in hypoxia-induced apoptosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 331, 718–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thijssen, R.; Diepstraten, S.T.; Moujalled, D.; Chew, E.; Flensburg, C.; Shi, M.X.; Dengler, M.A.; Litalien, V.; MacRaild, S.; Chen, M.; et al. Intact TP-53 function is essential for sustaining durable responses to BH3-mimetic drugs in leukemias. Blood 2021, 137, 2721–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diepstraten, S.T.; Yuan, Y.; Marca, J.E.L.; Young, S.; Chang, C.; Whelan, L.; Ross, A.M.; Fischer, K.C.; Pomilio, G.; Morris, R.; et al. Putting the STING back into BH3-mimetic drugs for TP53-mutant blood cancers. Cancer Cell 2024, 42, 850–868.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motwani, M.; Pesiridis, S.; Fitzgerald, K.A. DNA sensing by the cGAS–STING pathway in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 657–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eitz Ferrer, P.; Potthoff, S.; Kirschnek, S.; Gasteiger, G.; Kastenmüller, W.; Ludwig, H.; Paschen, S.A.; Villunger, A.; Sutter, G.; Drexler, I.; et al. Induction of Noxa-mediated apoptosis by modified vaccinia virus Ankara depends on viral recognition by cytosolic helicases, leading to IRF-3/IFN-β-dependent induction of pro-apoptotic Noxa. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulen, M.F.; Koch, U.; Haag, S.M.; Schuler, F.; Apetoh, L.; Villunger, A.; Radtke, F.; Ablasser, A. Signalling strength determines proapoptotic functions of STING. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamdouh, A.M.; Lim, F.Q.; Mi, Y.; Olesinski, E.A.; Chan, C.G.T.; Jasdanwala, S.; Lin, X.X.; Wang, Y.; Tan, J.Y.M.; Bhatia, K.S.; et al. Targetable BIRC5 dependency in therapy-resistant TP53 mutated acute myeloid leukemia. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marusawa, H.; Matsuzawa, S.-I.; Welsh, K.; Zou, H.; Armstrong, R.; Tamm, I.; Reed, J.C. HBXIP functions as a cofactor of survivin in apoptosis suppression. EMBO J. 2003, 22, 2729–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohi, T.; Okada, K.; Xia, F.; Wilford, C.E.; Samuel, T.; Welsh, K.; Marusawa, H.; Zou, H.; Armstrong, R.; Matsuzawa, S.; et al. An IAP-IAP complex inhibits apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 34087–34090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratton, S.B.; Walker, G.; Srinivasula, S.M.; Sun, X.-M.; Butterworth, M.; Alnemri, E.S.; Cohen, G.M. Recruitment, activation and retention of caspases-9 and -3 by Apaf-1 apoptosome and associated XIAP complexes. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 998–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikhil, K.; Shah, K. The significant others of aurora kinase a in cancer: Combination is the key. Biomark. Res. 2024, 12, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Simon, R. Identification of potential synthetic lethal genes to p53 using a computational biology approach. BMC Med. Genom. 2013, 6, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatz, S.A.; Wiesmüller, L. p53 in recombination and repair. Cell Death Differ. 2006, 13, 1003–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valikhani, M.; Rahimian, E.; Ahmadi, S.E.; Chegeni, R.; Safa, M. Involvement of classic and alternative non-homologous end joining pathways in hematologic malignancies: Targeting strategies for treatment. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 10, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asai, T.; Liu, Y.; Bae, N.; Nimer, S.D. The p53 tumor suppressor protein regulates hematopoietic stem cell fate. J. Cell. Physiol. 2011, 226, 2215–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Elf, S.E.; Miyata, Y.; Sashida, G.; Liu, Y.; Huang, G.; Di Giandomenico, S.; Lee, J.M.; Deblasio, A.; Menendez, S.; et al. p53 regulates hematopoietic stem cell quiescence. Cell Stem Cell 2009, 4, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, H.L.; Southgate, H.; Tweddle, D.A.; Curtin, N.J. DNA damage checkpoint kinases in cancer. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2020, 22, e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, H.J.; Oetjen, K.A.; Miller, C.A.; Ramakrishnan, S.M.; Day, R.B.; Helton, N.M.; Fronick, C.C.; Fulton, R.S.; Heath, S.E.; Tarnawsky, S.P.; et al. Genomic landscape of TP53-mutated myeloid malignancies. Blood Adv. 2023, 7, 4586–4598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, P.D.; Jasper, H.; Rudolph, K.L. Aging-Induced Stem Cell Mutations as Drivers for Disease and Cancer. Cell Stem Cell 2015, 16, 601–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperling, A.S.; Gibson, C.J.; Ebert, B.L. The genetics of myelodysplastic syndrome: From clonal haematopoiesis to secondary leukaemia. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Gao, R.; Yao, C.; Kobayashi, M.; Liu, S.Z.; Yoder, M.C.; Broxmeyer, H.; Kapur, R.; Boswell, H.S.; Mayo, L.D.; et al. Genotoxic stresses promote clonal expansion of hematopoietic stem cells expressing mutant p53. Leukemia 2018, 32, 850–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bondar, T.; Medzhitov, R. p53-Mediated Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cell Competition. Cell Stem Cell 2010, 6, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Nakada, D.; Goodell, M. Distinct landscape and clinical implications of therapy-related clonal hematopoiesis. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 134, e180069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ok, C.Y.; Patel, K.P.; Garcia-Manero, G.; Routbort, M.J.; Peng, J.; Tang, G.; Goswami, M.; Young, K.H.; Singh, R.; Medeiros, L.J.; et al. TP53 mutation characteristics in therapy-related myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myeloid leukemia is similar to de novo diseases. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2015, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, P.; Mencia-Trinchant, N.; Savenkov, O.; Simon, M.S.; Cheang, G.; Lee, S.; Samuel, M.; Ritchie, E.K.; Guzman, M.L.; Ballman, K.V.; et al. Somatic mutations precede acute myeloid leukemia years before diagnosis. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1015–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Miller, C.A.; Baty, J.; Ramesh, A.; Jotte, M.R.M.; Fulton, R.S.; Vogel, T.P.; Cooper, M.A.; Walkovich, K.J.; Makaryan, V.; et al. Somatic mutations and clonal hematopoiesis in congenital neutropenia. Blood 2018, 131, 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godley, L.A.; Larson, R.A. Therapy-related myeloid leukemia. Semin. Oncol. 2008, 35, 418–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klco, J.M.; Spencer, D.H.; Miller, C.A.; Griffith, M.; Lamprecht, T.L.; O’Laughlin, M.; Fronick, C.; Magrini, V.; Demeter, R.T.; Fulton, R.S.; et al. Functional Heterogeneity of Genetically Defined Subclones in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer Cell 2014, 25, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, B.Z.; Mak, P.Y.; Tao, W.; Ayoub, E.; Ostermann, L.B.; Huang, X.; Loghavi, S.; Boettcher, S.; Nishida, Y.; Ruvolo, V.; et al. Combined inhibition of BCL-2 and MCL-1 overcomes BAX deficiency-mediated resistance of TP53-mutant acute myeloid leukemia to individual BH3 mimetics. Blood Cancer J. 2023, 13, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nechiporuk, T.; Kurtz, S.E.; Nikolova, O.; Liu, T.; Jones, C.L.; D’Alessandro, A.; Culp-Hill, R.; d’Almeida, A.; Joshi, S.K.; Rosenberg, M.; et al. The TP53 Apoptotic Network is a Primary Mediator of Resistance to BCL2 inhibition in AML Cells. Cancer Discov. 2019, 9, 910–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Skwarska, A.; Poigaialwar, G.; Chaudhry, S.; Rodriguez-Meira, A.; Sui, P.; Olivier, E.; Jia, Y.; Gupta, V.; Fiskus, W.; et al. Efficacy of a novel BCL-xL degrader, DT2216, in preclinical models of JAK2-mutated post-MPN AML. Blood 2025, 146, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.E.; Hwang, D.Y.; Eom, J.-I.; Cheong, J.-W.; Jeung, H.-K.; Cho, H.; Chung, H.; Kim, J.S.; Min, Y.H. DRP1 Inhibition Enhances Venetoclax-Induced Mitochondrial Apoptosis in TP53-Mutated Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cells through BAX/BAK Activation. Cancers 2023, 15, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meric-Bernstam, F.; Sweis, R.F.; Hodi, F.S.; Messersmith, W.A.; Andtbacka, R.H.I.; Ingham, M.; Lewis, N.; Chen, X.; Pelletier, M.; Chen, X.; et al. Phase I Dose-Escalation Trial of MIW815 (ADU-S100), an Intratumoral STING Agonist, in Patients with Advanced/Metastatic Solid Tumors or Lymphomas. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 677–688, Erratum in Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 29, 2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vänttinen, I.; Ruokoranta, T.; Saad, J.J.; Kytölä, S.; Hellesøy, M.; Gullaksen, S.-E.; Ettala, P.-S.; Pyörälä, M.; Rimpiläinen, J.; Siitonen, T.; et al. Targeting Venetoclax Resistance in TP53-Mutated Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Blood 2023, 142 (Suppl. S1), 2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, R.J.; Thomas, A.; Rajan, A.; Chun, G.; Lopez-Chavez, A.; Szabo, E.; Spencer, S.; Carter, C.A.; Guha, U.; Khozin, S.; et al. A phase I/II study of sepantronium bromide (YM155, survivin suppressor) with paclitaxel and carboplatin in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 2013, 24, 2601–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, B.Z.; Mak, P.Y.; Ayoub, E.; Wu, X.; Ke, B.; Nishida, Y.; Futreal, A.; Ostermann, L.B.; Bedoy, A.D.; Boettcher, S.; et al. Restoring p53 wild-type conformation in TP53-Y220C-mutant acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2025, 146, 2574–2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, B.M.; Bae, Y.-H.; Koh, J.; Sun, J.-M.; Lee, S.-H.; Ahn, J.S.; Park, K.; Ahn, M.-J. Mutational status of TP53 defines the efficacy of Wee1 inhibitor AZD1775 in KRAS -mutant non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 67526–67537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Linden, A.A.; Baturin, D.; Ford, J.B.; Fosmire, S.P.; Gardner, L.; Korch, C.; Reigan, P.; Porter, C.C. Inhibition of Wee1 Sensitizes Cancer Cells to Antimetabolite Chemotherapeutics In Vitro and In Vivo, Independent of p53 Functionality. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2013, 12, 2675–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauro, G. ZN-c3 Shows Preliminary Efficacy, Safety in Recurrent/Advanced Uterine Serous Carcinoma|OncLive. Available online: https://www.onclive.com/view/zn-c3-shows-preliminary-efficacy-safety-in-recurrent-advanced-uterine-serous-carcinoma?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Ha, G.-H.; Breuer, E.-K.Y. Mitotic Kinases and p53 Signaling. Biochem. Res. Int. 2012, 2012, 195903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.-H.; Wu, D.; Perez-Losada, J.; Jiang, T.; Li, Q.; Neve, R.M.; Gray, J.W.; Cai, W.-W.; Balmain, A. Crosstalk between Aurora-A and p53: Frequent Deletion or Downregulation of Aurora-A in Tumors from p53 Null Mice. Cancer Cell 2007, 11, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SELLAS Announces Positive Overall Survival in Cohort 3 from the Ongoing Phase 2 Trial of SLS009 in r/r AML. Available online: https://ir.sellaslifesciences.com/news/News-Details/2025/SELLAS-Announces-Positive-Overall-Survival-in-Cohort-3-from-the-Ongoing-Phase-2-Trial-of-SLS009-in-rr-AML/default.aspx (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Lo-Coco, F.; Avvisati, G.; Vignetti, M.; Thiede, C.; Orlando, S.M.; Iacobelli, S.; Ferrara, F.; Fazi, P.; Cicconi, L.; Bona, E.D.; et al. Retinoic Acid and Arsenic Trioxide for Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Löwenberg, B.; Muus, P.; Ossenkoppele, G.; Rousselot, P.; Cahn, J.-Y.; Ifrah, N.; Martinelli, G.; Amadori, S.; Berman, E.; Sonneveld, P.; et al. Phase 1/2 study to assess the safety, efficacy, and pharmacokinetics of barasertib (AZD1152) in patients with advanced acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2011, 118, 6030–6036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantarjian, H.M.; Sekeres, M.A.; Ribrag, V.; Rousselot, P.; Garcia-Manero, G.; Jabbour, E.J.; Owen, K.; Stockman, P.K.; Oliver, S.D. Phase I study assessing the safety and tolerability of barasertib (AZD1152) with low-dose cytosine arabinoside in elderly patients with AML. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2013, 13, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantarjian, H.M.; Martinelli, G.; Jabbour, E.J.; Quintás-Cardama, A.; Ando, K.; Bay, J.O.; Wei, A.; Gröpper, S.; Papayannidis, C.; Owen, K.; et al. Stage i of a phase 2 study assessing the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of barasertib (AZD1152) versus low-dose cytosine arabinoside in elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer 2013, 119, 2611–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowska, M.; Muvarak, N.; Lapidus, R.G.; Sausville, E.A.; Bannerji, R.; Gojo, I. Single Agent Activity of the Cyclin-Dependent Kinase (CDK) Inhibitor Dinaciclib (SCH 727965) In Acute Myeloid and Lymphoid Leukemia Cells. Blood 2010, 116, 3981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gojo, I.; Sadowska, M.; Walker, A.; Feldman, E.J.; Iyer, S.P.; Baer, M.R.; Sausville, E.A.; Lapidus, R.G.; Zhang, D.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Clinical and laboratory studies of the novel cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor dinaciclib (SCH 727965) in acute leukemias. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2013, 72, 897–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Fu, W.; Xu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, J.; Hou, J.; Zhong, H. Arsenic Trioxide Combine with G-CSF Triggers Distinct TP53 Mutations Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cells Ferroptosis through TP53-SLC7A11-GPX4 Pathway. Blood 2023, 142 (Suppl. S1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, S.; Cho, S.J.; Chen, X. Mutant p53 Protein Is Targeted by Arsenic for Degradation and Plays a Role in Arsenic-mediated Growth Suppression. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 17478–17486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, K.; Wang, J.; Zhu, J.; Jiang, J.; Shou, J.; Chen, X. p53 induces TAP1 and enhances the transport of MHC class I peptides. Oncogene 1999, 18, 7740–7747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Niu, D.; Lai, L.; Ren, E.C. p53 increases MHC class I expression by upregulating the endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase ERAP1. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, T.; Jiang, J.; Guo, H.; Yang, R. p53 mutation and deletion contribute to tumor immune evasion. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1088455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Tan, J.Y.M.; Chitkara, N.; Bhatt, S. TP53 Mutation-Mediated Immune Evasion in Cancer: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications. Cancers 2024, 16, 3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Benetti, C.; Lin, X.X.; Dasdemir, E.; Hyroššová, P.; Tan, J.Y.M.; Ayoub, E.; Bhatia, K.S.; Lim, F.Q.; et al. Macrophage-secreted Pyrimidine Metabolites Confer Chemotherapy Resistance in Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML). bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravandi, F.; Assi, R.; Daver, N.; Benton, C.B.; Kadia, T.; Thompson, P.A.; Borthakur, G.; Alvarado, Y.; Jabbour, E.J.; Konopleva, M.; et al. Idarubicin, cytarabine, and nivolumab in patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukaemia or high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome: A single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Haematol. 2019, 6, e480–e488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daver, N.; Garcia-Manero, G.; Basu, S.; Boddu, P.C.; Alfayez, M.; Cortes, J.E.; Konopleva, M.; Ravandi-Kashani, F.; Jabbour, E.; Kadia, T.; et al. Efficacy, Safety, and Biomarkers of Response to Azacitidine and Nivolumab in Relapsed/Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Nonrandomized, Open-Label, Phase II Study. Cancer Discov. 2019, 9, 370–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidner, J.F.; Vincent, B.G.; Ivanova, A.; Moore, D.; McKinnon, K.P.; Wilkinson, A.D.; Mukhopadhyay, R.; Mazziotta, F.; Knaus, H.A.; Foster, M.C.; et al. Phase II Trial of Pembrolizumab after High-Dose Cytarabine in Relapsed/Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Blood Cancer Discov. 2021, 2, 616–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunner, A.M.; Esteve, J.; Porkka, K.; Knapper, S.; Traer, E.; Scholl, S.; Garcia-Manero, G.; Vey, N.; Wermke, M.; Janssen, J.J.W.M.; et al. Phase Ib study of sabatolimab (MBG453), a novel immunotherapy targeting TIM-3 antibody, in combination with decitabine or azacitidine in high- or very high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes. Am. J. Hematol. 2024, 99, E32–E36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeidan, A.M.; Westermann, J.; Kovacsovics, T.; Assouline, S.; Schuh, A.C.; Kim, H.J.; Macias, G.R.; Sanford, D.; Luskin, M.R.; Stein, E.M.; et al. AML-484 First Results of a Phase II Study (STIMULUS-AML1) Investigating Sabatolimab + Azacitidine + Venetoclax in Patients With Newly Diagnosed Acute Myeloid Leukemia (ND AML). Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2022, 22, S255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, F. VIP Expression Drives an Immunosuppressive Tumor Microenvironment in TP53-Mutated AML; ASH: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Available online: https://ash.confex.com/ash/2024/webprogram/Paper208170.html (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Petersen, C.T.; Li, J.-M.; Waller, E.K. Administration of a vasoactive intestinal peptide antagonist enhances the autologous anti-leukemia T cell response in murine models of acute leukemia. Oncoimmunology 2017, 6, e1304336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidan, A.; Stein, A.; Sallman, D.; Zeidner, J.; Maher, K.; Curran, E.; Bixby, D.; Chai-Ho, W.; Stahl, M.; Yee, K.; et al. Phase 1B Study of SL-172154, a Bi-Functional Fusion Protein. Available online: https://library.ehaweb.org/eha/2024/eha2024-congress/420837/amer.zeidan.phase.1b.study.of.sl-172154.a.bi-functional.fusion.protein.html?f=listing%3D6%2Abrowseby%3D8%2Asortby%3D2%2Atopic%3D1574%2Asearch%3Dcd47&utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Tan, J.Y.M.; Tan, J.C.; Wang, C.; Wu, L.; Gascoigne, N.R.J.; Bhatt, S. Protocol for the simultaneous activation and lentiviral transduction of primary human T cells with artificial T cell receptors. STAR Protoc. 2025, 6, 103685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirgayazova, R.; Khadiullina, R.; Filimonova, M.; Chasov, V.; Bulatov, E. Impact of TP53 mutations on the efficacy of CAR-T cell therapy in cancer. Explor. Immunol. 2024, 4, 837–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, J.; Schimmer, R.R.; Koch, C.; Schneiter, F.; Fullin, J.; Lysenko, V.; Pellegrino, C.; Klemm, N.; Russkamp, N.; Myburgh, R.; et al. Targeting the mevalonate or Wnt pathways to overcome CAR T-cell resistance in TP53-mutant AML cells. EMBO Mol. Med. 2024, 16, 445–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zugasti, I.; Espinosa-Aroca, L.; Fidyt, K.; Mulens-Arias, V.; Diaz-Beya, M.; Juan, M.; Urbano-Ispizua, Á.; Esteve, J.; Velasco-Hernandez, T.; Menéndez, P. CAR-T cell therapy for cancer: Current challenges and future directions. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maucher, M.; Srour, M.; Danhof, S.; Einsele, H.; Hudecek, M.; Yakoub-Agha, I. Current Limitations and Perspectives of Chimeric Antigen Receptor-T-Cells in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancers 2021, 13, 6157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Khawanky, N. Novel CAR T cells to combat antigen escape in AML. Blood 2025, 145, 657–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, H.J.; Martin, G.; Birocchi, F.; Wehrli, M.; Kann, M.C.; Supper, V.; Parker, A.; Graham, C.; Bratt, A.; Bouffard, A.; et al. CD70 CAR T cells secreting an anti-CD33/anti-CD3 dual-targeting antibody overcome antigen heterogeneity in AML. Blood 2025, 145, 720–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, C.; Deng, J.; Hu, Y.; Mei, H.; Luo, S. Recent advances of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for acute myeloid leukemia. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1572407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarychta, J.; Kowalczyk, A.; Krawczyk, M.; Lejman, M.; Zawitkowska, J.; Zarychta, J.; Kowalczyk, A.; Krawczyk, M.; Lejman, M.; Zawitkowska, J. CAR-T Cells Immunotherapies for the Treatment of Acute Myeloid Leukemia—Recent Advances. Cancers 2023, 15, 2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canichella, M.; Molica, M.; Mazzone, C.; de Fabritiis, P.; Canichella, M.; Molica, M.; Mazzone, C.; de Fabritiis, P. Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy in Acute Myeloid Leukemia: State of the Art and Recent Advances. Cancers 2023, 16, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skuli, S.J.; Bakayoko, A.; Kruidenier, M.; Manning, B.; Pammer, P.; Salimov, A.; Riley, O.; Brake-Sillá, G.; Dopkin, D.; Bowman, M.; et al. Chemoresistance of TP53 mutant acute myeloid leukemia requires the mevalonate byproduct, geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate, for induction of an adaptive stress response. Leukemia 2025, 39, 2087–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, Y.; Fard, J.K.; Ghafoor, D.; Eid, A.H.; Sahebkar, A. Paradoxical effects of statins on endothelial and cancer cells: The impact of concentrations. Cancer Cell Int. 2023, 23, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semba, Y.; Yamauchi, T.; Nakao, F.; Nogami, J.; Canver, M.C.; Pinello, L.; Bauer, D.E.; Akashi, K.; Maeda, T. CRISPR-Cas9 Screen Identifies XPO7 As a Potential Therapeutic Target for TP53-Mutated AML. Blood 2019, 134 (Suppl. S1), 3784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malani, D.; Kumar, A.; Brück, O.; Kontro, M.; Yadav, B.; Hellesøy, M.; Kuusanmäki, H.; Dufva, O.; Kankainen, M.; Eldfors, S.; et al. Implementing a Functional Precision Medicine Tumor Board for Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 388–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuusanmäki, H.; Kytölä, S.; Vänttinen, I.; Ruokoranta, T.; Ranta, A.; Huuhtanen, J.; Suvela, M.; Parsons, A.; Holopainen, A.; Partanen, A.; et al. Ex vivo venetoclax sensitivity testing predicts treatment response in acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica 2023, 108, 1768–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swords, R.T.; Azzam, D.; Al-Ali, H.; Lohse, I.; Volmar, C.-H.; Watts, J.M.; Perez, A.; Rodriguez, A.; Vargas, F.; Elias, R.; et al. Ex-vivo Sensitivity Profiling to Guide Clinical Decision Making in Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Pilot Study. Leuk. Res. 2018, 64, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, P.S. Potent Personalized Venetoclax Partners for Acute Myeloid Leukemia Identified by Ex Vivo Drug Screening. Blood Cancer Discov. 2023, 4, 437–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyner, J.W.; Tognon, C.E.; Bottomly, D.; Wilmot, B.; Kurtz, S.E.; Savage, S.L.; Long, N.; Schultz, A.R.; Traer, E.; Abel, M.; et al. Functional genomic landscape of acute myeloid leukaemia. Nature 2018, 562, 526–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bottomly, D.; Long, N.; Schultz, A.R.; Kurtz, S.E.; Tognon, C.E.; Johnson, K.; Abel, M.; Agarwal, A.; Avaylon, S.; Benton, E.; et al. Integrative analysis of drug response and clinical outcome in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell 2022, 40, 850–864.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J.; Letai, A. BH3 profiling in whole cells by fluorimeter or FACS. Methods 2013, 61, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olesinski, E.A.; Bhatt, S. Dynamic BH3 profiling method for rapid identification of active therapy in BH3 mimetics resistant xenograft mouse models. STAR Protoc. 2021, 2, 100461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olesinski, E.A.; Bhatia, K.S.; Wang, C.; Pioso, M.S.; Lin, X.X.; Mamdouh, A.M.; Ng, S.X.; Sandhu, V.; Jasdanwala, S.S.; Yilma, B.; et al. Acquired Multidrug Resistance in AML Is Caused by Low Apoptotic Priming in Relapsed Myeloblasts. Blood Cancer Discov. 2024, 5, 180–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olesinski, E.A.; Bhatia, K.S.; Mahesh, A.N.; Rosli, S.; Mohamed, J.S.; Jen, W.Y.; Jain, N.; Garcia, J.S.; Wong, G.C.; Ooi, M.; et al. BH3 profiling identifies BCL-2 dependence in adult patients with early T-cell progenitor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood Adv. 2023, 7, 2917–2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, R.A.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, S.; Villalobos-Ortiz, M.; Ryan, J.; Morris, E.; Halilovic, E.; Letai, A. BH3 profiling as pharmacodynamic biomarker for the activity of BH3 mimetics. Haematologica 2024, 109, 1253–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhola, P.D.; Ahmed, E.; Guerriero, J.L.; Sicinska, E.; Su, E.; Lavrova, E.; Ni, J.; Chipashvili, O.; Hagan, T.; Pioso, M.S.; et al. High-throughput dynamic BH3 profiling may quickly and accurately predict effective therapies in solid tumors. Sci. Signal. 2020, 13, eaay1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, D.S.; Du, R.; Bhola, P.; Bueno, R.; Letai, A. Dynamic BH3 profiling identifies active BH3 mimetic combinations in non-small cell lung cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burack, W.R.; Li, H.; Adlowitz, D.; Spence, J.M.; Rimsza, L.M.; Shadman, M.; Spier, C.M.; Kaminski, M.S.; Leonard, J.P.; Leblanc, M.L.; et al. Subclonal TP53 mutations are frequent and predict resistance to radioimmunotherapy in follicular lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2023, 7, 5082–5090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasca, S.; Haldar, S.D.; Ambinder, A.; Webster, J.A.; Jain, T.; Dalton, W.B.; Prince, G.T.; Ghiaur, G.; DeZern, A.E.; Gojo, I.; et al. Outcome heterogeneity of TP53-mutated myeloid neoplasms and the role of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Haematologica 2024, 109, 948–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morita, K.; Wang, F.; Jahn, K.; Hu, T.; Tanaka, T.; Sasaki, Y.; Kuipers, J.; Loghavi, S.; Wang, S.A.; Yan, Y.; et al. Clonal evolution of acute myeloid leukemia revealed by high-throughput single-cell genomics. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, J.; Xiao, M. Next-generation sequencing for MRD monitoring in B-lineage malignancies: From bench to bedside. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 11, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saygin, C.; Cannova, J.; Stock, W.; Muffly, L. Measurable residual disease in acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Methods and clinical context in adult patients. Haematologica 2022, 107, 2783–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Solis-Ruiz, J.; Yang, F.; Long, N.; Tong, C.H.; Lacbawan, F.L.; Racke, F.K.; Press, R.D. NGS-defined measurable residual disease (MRD) after initial chemotherapy as a prognostic biomarker for acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Cancer J. 2023, 13, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeraraghavan, V.P.; Doni, B.R.; Dasari, A.K.; Patil, C.; Rao, K.A.; Patil, S.R. Deciphering genomic complexity: Understanding intratumor heterogeneity, clonal evolution, and therapeutic vulnerabilities in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. Rep. 2024, 10, 100469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallman, D.A.; Stahl, M. TP53-mutated acute myeloid leukemia: How can we improve outcomes? Blood 2025, 145, 2828–2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Zheng, J.; Weng, Y.; Wu, Z.; Luo, X.; Qiu, Y.; Lin, Y.; Hu, J.; Wu, Y. Myelodysplasia-related gene mutations are associated with favorable prognosis in patients with TP53-mutant acute myeloid leukemia. Ann. Hematol. 2024, 103, 1211–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prochazka, K.T.; Pregartner, G.; Rücker, F.G.; Heitzer, E.; Pabst, G.; Wölfler, A.; Zebisch, A.; Berghold, A.; Döhner, K.; Sill, H. Clinical implications of subclonal TP53 mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica 2019, 104, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badar, T.; Nanaa, A.; Atallah, E.; Shallis, R.M.; Craver, E.C.; Li, Z.; Goldberg, A.D.; Saliba, A.N.; Patel, A.; Bewersdorf, J.P.; et al. Prognostic impact of ‘multi-hit’ versus ‘single-hit’ TP53 alteration in patients with acute myeloid leukemia: Results from the Consortium on Myeloid Malignancies and Neoplastic Diseases. Haematologica 2024, 109, 3533–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalban-Bravo, G.; Benton, C.B.; Wang, S.A.; Ravandi, F.; Kadia, T.; Cortes, J.; Daver, N.; Takahashi, K.; DiNardo, C.; Jabbour, E.; et al. More than 1 TP53 abnormality is a dominant characteristic of pure erythroid leukemia. Blood 2017, 129, 2584–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döhner, H.; DiNardo, C.D.; Appelbaum, F.R.; Craddock, C.; Dombret, H.; Ebert, B.L.; Fenaux, P.; Godley, L.A.; Hasserjian, R.P.; Larson, R.A.; et al. Genetic risk classification for adults with AML receiving less-intensive therapies: The 2024 ELN recommendations. Blood 2024, 144, 2169–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Guidelines for Patients: Acute Myeloid Leukemia; National Comprehensive Cancer Network: Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, M.V.; Arber, D.A.; Hiwase, D.K. TP53-Mutated Myeloid Neoplasms: 2024 Update on Diagnosis, Risk-Stratification, and Management. Am. J. Hematol. 2025, 100, 88–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Vicente, C.; Esteve, J.; Baile-González, M.; Pérez-López, E.; Martin Calvo, C.; Aparicio, C.; Oiartzabal Ormategi, I.; Esquirol, A.; Peña-Muñoz, F.; Fernández-Luis, S.; et al. Allo-HCT refined ELN 2022 risk classification: Validation of the Adverse-Plus risk group in AML patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation within the Spanish Group for Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation (GETH-TC). Blood Cancer J. 2025, 15, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loizou, E.; Banito, A.; Livshits, G.; Ho, Y.-J.; Koche, R.P.; Sánchez-Rivera, F.J.; Mayle, A.; Chen, C.-C.; Kinalis, S.; Bagger, F.O.; et al. A Gain-of-Function p53-Mutant Oncogene Promotes Cell Fate Plasticity and Myeloid Leukemia through the Pluripotency Factor FOXH1. Cancer Discov. 2019, 9, 962–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, M.; Chen, Z.; Tian, J.; Peng, Y.; Song, D.; Zhang, L.; Jin, Y. Exosomes derived from programmed cell death: Mechanism and biological significance. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, J.; You, D.; Breslin, P.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Wei, W.; Cannova, J.; Volk, A.; Gutierrez, R.; Xiao, Y.; et al. Sensitizing Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cells to Induced Differentiation by Inhibiting the RIP1/RIP3 Pathway. Leukemia 2017, 31, 1154–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Kon, N.; Li, T.; Wang, S.-J.; Su, T.; Hibshoosh, H.; Baer, R.; Gu, W. Ferroptosis as a p53-mediated activity during tumour suppression. Nature 2015, 520, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, C.; Wang, J.; Hu, W.; Feng, Z. The Regulation of Ferroptosis by Tumor Suppressor p53 and its Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Stockwell, B.R.; Jiang, X.; Gu, W. p53-regulated non-apoptotic cell death pathways and their relevance in cancer and other diseases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2025, 26, 600–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birsen, R.; Larrue, C.; Decroocq, J.; Johnson, N.; Guiraud, N.; Gotanegre, M.; Cantero-Aguilar, L.; Grignano, E.; Huynh, T.; Fontenay, M.; et al. APR-246 induces early cell death by ferroptosis in acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica 2022, 107, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Hong, X.; Huang, X.; Jiang, X.; Jiang, H.; Huang, Y.; Wu, W.; Xue, Y.; Lin, D. Comprehensive analysis of ferroptosis-related gene signatures as a potential therapeutic target for acute myeloid leukemia: A bioinformatics analysis and experimental verification. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 930654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auberger, P.; Favreau, C.; Savy, C.; Jacquel, A.; Robert, G. Emerging role of glutathione peroxidase 4 in myeloid cell lineage development and acute myeloid leukemia. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2024, 29, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, D.E.; Cui, Z. Triggering Pyroptosis in Cancer. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, C.; Wang, R.; Hua, M.; Zhang, C.; Han, F.; Xu, M.; Yang, X.; Li, G.; Hu, X.; Sun, T.; et al. NLRP3 Inflammasome Promotes the Progression of Acute Myeloid Leukemia via IL-1β Pathway. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 661939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.C.; Taabazuing, C.Y.; Okondo, M.C.; Chui, A.J.; Rao, S.D.; Brown, F.C.; Reed, C.; Peguero, E.; de Stanchina, E.; Kentsis, A.; et al. DPP8/DPP9 inhibitor-induced pyroptosis for treatment of acute myeloid leukemia. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1151–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folkerts, H.; Hilgendorf, S.; Wierenga, A.T.J.; Jaques, J.; Mulder, A.B.; Coffer, P.J.; Schuringa, J.J.; Vellenga, E. Inhibition of autophagy as a treatment strategy for p53 wild-type acute myeloid leukemia. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, W.; Xu, A.; Huang, Y.; Cao, J.; Zhu, H.; Yang, B.; Shao, X.; He, Q.; Ying, M. The role of autophagy in targeted therapy for acute myeloid leukemia. Autophagy 2020, 17, 2665–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, P.M.P.; de Sousa, R.W.R.; Ferreira, J.R.d.O.; Militão, G.C.G.; Bezerra, D.P. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in antitumor therapies based on autophagy-related mechanisms. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 168, 105582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | Percent with CR | Overall Survival |

|---|---|---|

| Induction Chemotherapy | 20–40% | 5–9 months |

| VenAza | 41% | 5.2 months |

| Allogenic Stem Cell Transplant | --- | 24.5 months |

| Clinical Trial ID | Phase | Patient Age | TP53 Mutant | Drug Tested | Participation Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT03072043 * | 1/2 | ≥18 years |

All TP53 mutants | Eprenetapopt (p53 stabilizer) + azacitidine | MDS, MDS/myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN), chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) or oligoblastic AML (20–30% myeloblasts) |

| NCT03745716 * | 3 | ≥18 years |

All TP53 mutants | Eprenetapopt (p53 stabilizer) + azacitidine | MDS |

| NCT02909972 * | 1 | ≥18 years |

All TP53 Wild-type | Sulanemadlin (p53-MDM2/MDMX disrupter) ± cytarabine | R/R AML or IPSS-R intermediate/high/very high risk MDS |

| NCT00623870 * | 1 | ≥18 years | 14% patients with TP53 mutations | RG7112 (MDM2 inhibitor) | R/R AML, ALL, CML in blast phase, CLL, or SLL |

| NCT01975116 * | 1 | 3–21 years |

Some TP53 mutants | p28 | R/R high grade glioma (glioblastoma multiforme, medulloblastoma, primitive neuroectodermal tumor, atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor, anaplastic astrocytoma, high-grade astrocytoma not otherwise specified (NOS), anaplastic oligodendroglioma, or choroid plexus carcinoma; or diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma) |

| NCT00914914 * | 1 | ≥18 years |

All TP53 mutants | p28 | R/R metastatic solid tumors |

| NCT03248479 X | 1 | ≥18 years | 82.8% patients with TP53 mutations | Magrolimab (humanized anti-CD47 monoclonal antibody) ± azacitidine | R/R AML or high-risk MDS |

| NCT04778397 X | 3 | ≥18 years |

All TP53 mutants | Magrolimab (humanized anti-CD47 monoclonal antibody) ± azacitidine or VenAza | Previously untreated AML |

| NCT03013998 X | 1/2 | ≥18 years |

All TP53 mutants | Entospletinib (SYK inhibitor) + azacitidine or decitabine or daunorubicin and cytarabine | Previously untreated AML |

| Clinical Trial ID | Phase | Patient Age | TP53 Mutant | Drug Tested | Participation Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT02675452 # | 1 | 18–85 years | Unspecified | AMG176 (MCL-1 inhibitor) ± azacitidine or itraconazole | R/R AML and multiple myeloma |

| NCT04886622 * | 1 | ≥18 years | Unspecified | DT2216 (BCL-xL degrader) | Hematologic or solid malignancies that exhausted standard of care measures |

| NCT02675439 X | 1 | ≥18 years | Unspecified | ADU-S100 (STING agonist) ± ipilimumab | Advanced lymphoma or metastatic solid tumors |

| NCT01100931 * | 1/2 | ≥18 years | Unspecified | YM155 (survivin inhibitor) + paclitaxel + carboplatin | Advanced non-small cell lung cancer |

| NCT06616636 ↑ | 1 | ≥18 years | All TP53-Y220C mutants | Rezatapopt (small molecule that binds the p53 structural pocket) | TP53-Y220C mutant MDS and AML |

| NCT02095132 * | 1 | 1–21 years | Unspecified | Adavosertib (WEE1 inhibitor) + irinotecan | R/R solid tumors in pediatric patients |

| NCT04158336 ? | 1 | ≥18 years | Unspecified | Azenosertib (WEE1 inhibitor) | R/R advanced or metastatic solid tumors |

| NCT00497991 * | 1 | ≥18 years | Unspecified | Barasertib (Aurora B kinase inhibitor) | R/R AML |

| NCT00926731 * | 1/2 | ≥60 years | Unspecified | Barasertib (Aurora B kinase inhibitor) ± cytosine arabinoside | Newly diagnosed de novo or secondary AML ineligible for intensive induction chemotherapy |

| NCT00952588 * | 2/3 | ≥60 years | Unspecified | Barasertib (Aurora B kinase inhibitor) ± cytosine arabinoside | Newly diagnosed de novo or secondary AML ineligible for intensive induction chemotherapy |

| NCT03484520 # | 1 | ≥18 years | Unspecified | Dinaciclib (CDK inhibitor) + venetoclax | R/R AML |

| NCT04588922 ↑ | 2 | ≥12 years | 3 patients with TP53 mutants | SLS009 (CDK9 inhibitor) + VenAza | R/R AML, CLL, SLL, and lymphoma |

| NCT03381781 ? | 2 | 18–75 years |

All TP53 mutants | Arsenic trioxide + decitabine or cytarabine | De novo AML, AML transferred from MDS, therapy-related AML; all are TP53 mutant |

| NCT02464657 * | 2 | ≥18 years |

Included TP53 mutant | Nivolumab (anti-PD-1 antibody) + idarubicin or cytarabine | Newly diagnosed high-risk MDS/AML patients |

| NCT02397720 * | 2 | ≥18 years | 16 patients with TP53 mutants | Nivolumab (anti-PD-1 antibody) + azacitidine ± ipilimumab | R/R AML or newly diagnosed AML unfit for standard induction chemotherapy |

| NCT02768792 * | 2 | 18–70 years | 5 patients with TP53 mutants | Pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1 antibody) after cytarabine | R/R AML |

| NCT03066648 * | 1 | ≥18 years |

Included TP53 mutants | Sabatolimab (anti-TIM-3 antibody) + decitabine | High-risk MDS or R/R AML |

| NCT05275439 * | 1 | ≥18 years |

Included TP53 mutants | SL-172154 (SIRPα-Fc-CD40L) ± VenAza or azacitidine alone | High-risk MDS or R/R AML |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Olesinski, E.A.; Bhatt, S. Pandora’s Box of AML: How TP53 Mutations Defy Therapy and Hint at New Hope. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 3007. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123007

Olesinski EA, Bhatt S. Pandora’s Box of AML: How TP53 Mutations Defy Therapy and Hint at New Hope. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):3007. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123007

Chicago/Turabian StyleOlesinski, Elyse A., and Shruti Bhatt. 2025. "Pandora’s Box of AML: How TP53 Mutations Defy Therapy and Hint at New Hope" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 3007. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123007