The Dual Role of RUNX1 in Inflammation-Driven Age-Related Diseases: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Translation

Abstract

1. Introduction

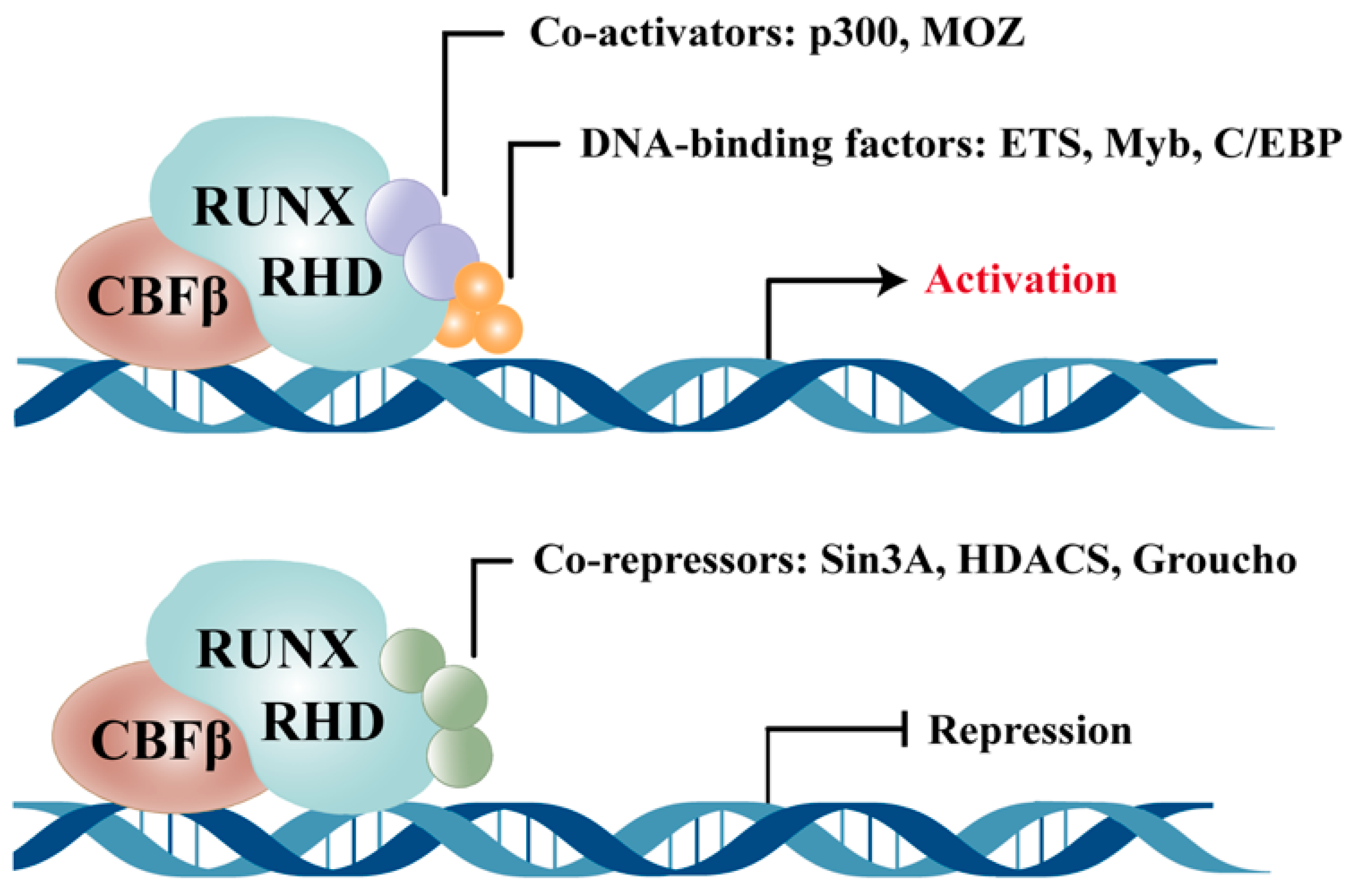

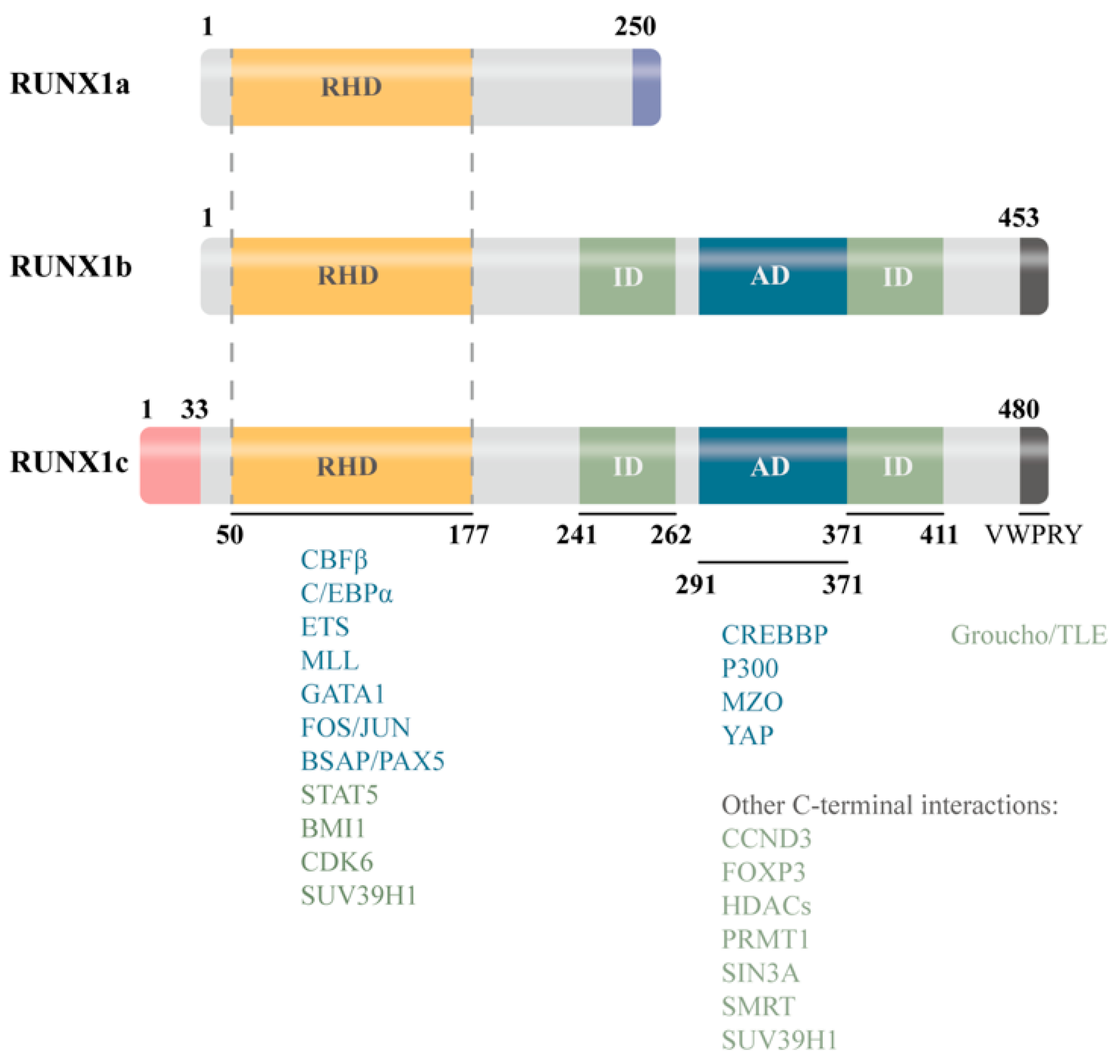

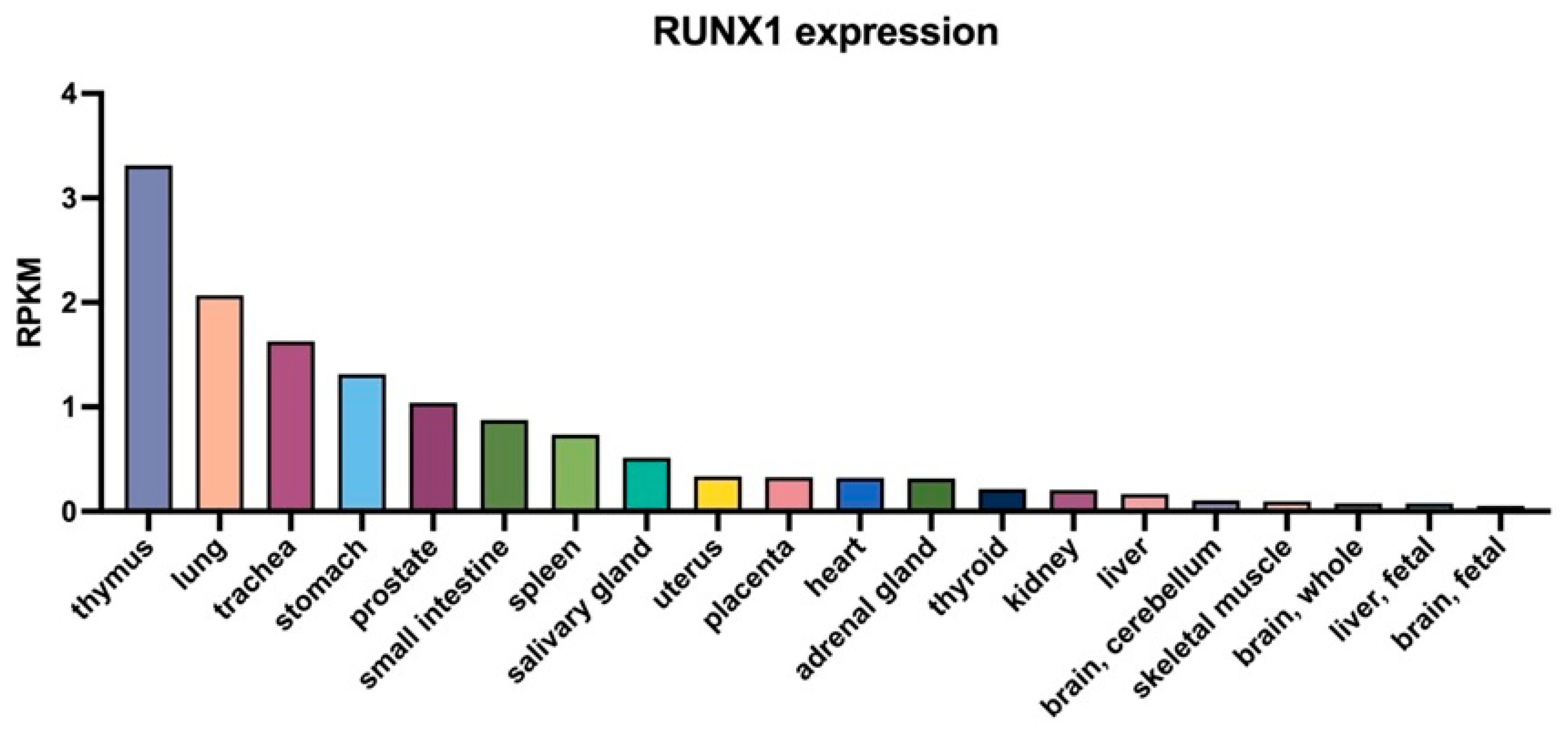

2. Molecular Characteristics and Expression Profile of RUNX1

3. RUNX1 in Age-Associated Inflammation

3.1. Inflammatory Signaling-Driven Activation of RUNX1

3.2. RUNX1-Mediated Tissue Dysfunction and Regenerative Impairment

3.3. Clinical Relevance and Translational Potential of RUNX1

3.4. Isoform-Specific Functional Dissection: The Foundation for Precision Targeting

3.5. Intervention Models and Temporal Control: Identifying the Therapeutic Window

3.6. Drug Development: From Transcriptional Inhibition to Precision Delivery

3.7. Clinical Trials and Disease Stratification: RUNX1 as a Dual-Purpose Biomarker

| System | Acute Inflammation | Chronic Inflammation | Key Mechanisms | Pathologies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory | Dual pro-/anti-inflammatory in ALI/ARDS | Sustains ILC2-driven airway inflammation | NF-κB, TGF-β, mitochondrial autophagy | ALI, ARDS, fibrosis, COPD, asthma [36,97,98] |

| Renal | Promotes tubular NF-κB/IL-6 activation | Persistent fibrosis signaling | NF-κB, IL-6 axis | AKI, CKD, renal fibrosis [35,99,100] |

| Digestive | JAK/STAT3-mediated protection; Resistin+ monocyte expansion | Drives NAFLD, fibrosis via stellate cell activation | JAK/STAT3, NF-κB, TNF | NAFLD, fibrosis, IBD [101,102,103] |

| Immune/Hematopoietic | Regulates neutrophil/B-cell activation; links hematopoiesis to inflammation | Th1/Th17 skewing, autoimmunity | NF-κB, CD74 axis | Autoimmune disease, RA, leukemia [27,104,105] |

| Cardiovascular | Upregulated post-MI, remodeling; downregulated in shock | Promotes atherosclerosis, fibroblast activation; protective in aneurysm | NF-κB, TGF-β, STAT3 | MI, heart failure, atherosclerosis, aneurysm [23,59,106,107,108] |

| Metabolic | Modulates acute pancreatitis | Insulin resistance, NAFLD, fibrosis | NF-κB, IL-6, TNF | Diabetes, NAFLD, fibrosis [109,110,111] |

| Nervous | Neuroprotective in acute injury | NLRP3-driven neurodegeneration | NF-κB, ROS, NLRP3 | Alzheimer’s, stroke, neurodegeneration [65,66,112] |

| Other | — | Chagas (FAK-NF-κB), psoriasis (STAT6/NFATC2), allergic airway inflammation (ILC2) | Multiple axes | Chagas, psoriasis, allergy [113,114,115] |

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AKI | Acute Kidney Injury |

| ALI | Acute Lung Injury |

| AMPK | 5′ AMP-activated protein kinase |

| ARDS | Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome |

| CBFβ | Core-binding factor beta |

| CKD | Chronic Kidney Disease |

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| CXCL1 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 1 |

| DNMTs | DNA Methyltransferases |

| eNOS | endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| HDACs | Histone Deacetylases |

| IFN-γ | Interferon gamma |

| IL-1β | Interleukin 1 beta |

| IL-6 | Interleukin 6 |

| IL-8 | Interleukin 8 |

| ILC2 | Innate Lymphoid Cell type 2 |

| JAK/STAT | Janus kinase/Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription |

| JNK | c-Jun N-terminal kinase |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MMPs | Matrix Metalloproteinases |

| MyD88 | Myeloid differentiation primary response 88 |

| NAFLD | Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NLRP3 | NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 |

| PI3K–Akt | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase—Protein kinase B |

| PU.1 | Transcription factor PU.1 |

| RA | Rheumatoid Arthritis |

| RHD | Runt homology domain |

| RNA-seq | RNA sequencing |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| RUNX1 | Runt-related transcription factor 1 |

| SASP | Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype |

| STAT3 | Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 |

| TGF-β | Transforming Growth Factor beta |

| TLR3 | Toll-like receptor 3 |

| TOLLIP | Toll-interacting protein |

| TGF-β | Transforming Growth Factor beta |

| TLR3 | Toll-like receptor 3 |

| TOLLIP | Toll-interacting protein |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha |

| ULK1 | Unc-51-like kinase 1 |

References

- Ajoolabady, A.; Pratico, D.; Tang, D.; Zhou, S.; Franceschi, C.; Ren, J. Immunosenescence and Inflammaging: Mechanisms and Role in Diseases. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 101, 102540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liang, Q.; Ren, Y.; Guo, C.; Ge, X.; Wang, L.; Cheng, Q.; Luo, P.; Zhang, Y.; Han, X. Immunosenescence: Molecular Mechanisms and Diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, E.; de Las Heras, M.M.G.; Gabandé-Rodríguez, E.; Desdín-Micó, G.; Aranda, J.F.; Mittelbrunn, M. The Role of T Cells in Age-Related Diseases. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2022, 22, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, R.; Kamikubo, Y.; Liu, P. Role of RUNX1 in hematological malignancies. Blood 2017, 129, 2070–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, P.J.; Babushok, D.V. Born to RUNX1. Blood 2020, 135, 1824–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, V.L.; Liu, P.; Katsumura, K.R.; Soukup, A.A.; Kopp, A.; Ahmad, Z.S.; Mattina, A.E.; Brand, M.; Johnson, K.D.; Bresnick, E.H. Dual mechanism of inflammation sensing by the hematopoietic progenitor genome. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadv3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Chen, W.; Masson, A.; Li, Y.P. Cell signaling and transcriptional regulation of osteoblast lineage commitment, differentiation, bone formation, and homeostasis. Cell Discov. 2024, 10, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukasiewicz, C.J.; Tranah, G.J.; Evans, D.S.; Coen, P.M.; Barnes, H.N.; Huo, Z.; Esser, K.A.; Zhang, X.; Wolff, C.; Wu, K.; et al. Higher expression of denervation-responsive genes is negatively associated with muscle volume and performance traits in the study of muscle, mobility, and aging (SOMMA). Aging Cell 2024, 23, e14115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.W.; Wang, B.Y.; Wong, S.H.; Chen, Y.F.; Cao, Q.; Hsiao, A.W.; Fung, S.H.; Chen, Y.F.; Wu, H.H.; Cheng, P.Y.; et al. Ginkgolide B increases healthspan and lifespan of female mice. Nat. Aging 2025, 5, 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes-Paciencia, S.; Bourdeau, V.; Rowell, M.C.; Amirimehr, D.; Guillon, J.; Kalegari, P.; Barua, A.; Quoc-Huy Trinh, V.; Azzi, F.; Turcotte, S.; et al. A senescence restriction point acting on chromatin integrates oncogenic signals. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 114044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Xia, T.; Wang, X.; Wang, H. Identification and validation of biomarkers based on cellular senescence in mild cognitive impairment. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2023, 15, 1139789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Yang, W.; Chen, F.M.; He, Q.; Ma, H.L.; Li, C.H.; Liang, M.L.; Zhong, J.Q.; Zhang, X.Z.; Li, F.R. IRF8 and RUNX1 cooperatively regulate the senescence and damage of urine-derived renal progenitor cells by upregulating LINC01806. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2025, 240, 117068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korinfskaya, S.; Parameswaran, S.; Weirauch, M.T.; Barski, A. Runx Transcription Factors in T Cells-What Is Beyond Thymic Development? Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 701924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, S.; Komeno, Y.; Stevenson, K.E.; Biggs, J.R.; Lam, K.; Tang, T.; Lo, M.C.; Cong, X.; Yan, M.; Neuberg, D.S.; et al. Expression of the runt homology domain of RUNX1 disrupts homeostasis of hematopoietic stem cells and induces progression to myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood 2012, 120, 4028–4037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gialesaki, S.; Bräuer-Hartmann, D.; Issa, H.; Bhayadia, R.; Alejo-Valle, O.; Verboon, L.; Schmell, A.L.; Laszig, S.; Regényi, E.; Schuschel, K.; et al. RUNX1 isoform disequilibrium promotes the development of trisomy 21-associated myeloid leukemia. Blood 2023, 141, 1105–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, L.; Voora, D.; Myers, R.; Del Carpio-Cano, F.; Rao, A.K. RUNX1 isoforms regulate RUNX1 and target genes differentially in platelets-megakaryocytes: Association with clinical cardiovascular events. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2024, 22, 3581–3598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvanese, V.; Capellera-Garcia, S.; Ma, F.; Fares, I.; Liebscher, S.; Ng, E.S.; Ekstrand, S.; Aguadé-Gorgorió, J.; Vavilina, A.; Lefaudeux, D.; et al. Mapping human haematopoietic stem cells from haemogenic endothelium to birth. Nature 2022, 604, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Tu, Z.; Cai, X.; Wang, W.; Davis, A.K.; Nattamai, K.; Paranjpe, A.; Dexheimer, P.; Wu, J.; Huang, F.L.; et al. A critical role of RUNX1 in governing megakaryocyte-primed hematopoietic stem cell differentiation. Blood Adv. 2023, 7, 2590–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimura, R.; Jha, D.K.; Han, A.; Soria-Valles, C.; da Rocha, E.L.; Lu, Y.F.; Goettel, J.A.; Serrao, E.; Rowe, R.G.; Malleshaiah, M.; et al. Haematopoietic stem and progenitor cells from human pluripotent stem cells. Nature 2017, 545, 432–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Zhong, L.; Tian, X.; Zou, Y.; Hu, S.; Liu, J.; Li, P.; Zhu, M.; Luo, F.; Wan, H. RUNX1 promotes mitophagy and alleviates pulmonary inflammation during acute lung injury. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozen, E.J.; Ozeroff, C.D.; Allen, M.A. RUN(X) out of blood: Emerging RUNX1 functions beyond hematopoiesis and links to Down syndrome. Hum. Genom. 2023, 17, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, B.R.; Wu, L.; Goodrich, L.V. Runx1 controls auditory sensory neuron diversity in mice. Dev. Cell 2023, 58, 306–319.e305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, T.P.; MacDonald, E.A.; Bradley, A.; Watson, H.; Saxena, P.; Rog-Zielinska, E.A.; Raheem, A.; Fisher, S.; Elbassioni, A.A.M.; Almuzaini, O.; et al. Ribonucleicacid interference or small molecule inhibition of Runx1 in the border zone prevents cardiac contractile dysfunction following myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023, 119, 2663–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, T.; Cao, Y.; Dou, T.; Chen, Y.; Lopez, G.; Menezes, A.C.; Wu, X.; Hammer, J.A.; Cheng, J.; Garrett, L.; et al. CBFβ-SMMHC-driven leukemogenesis requires enhanced RUNX1-DNA binding affinity in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2025, 135, e192923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamble, N.; Bradu, A.; Caldwell, J.A.; McKeever, J.; Bolonduro, O.; Ermis, E.; Kaiser, C.; Kim, Y.; Parks, B.; Klemm, S.; et al. PU.1 and BCL11B sequentially cooperate with RUNX1 to anchor mSWI/SNF to poise the T cell effector landscape. Nat. Immunol. 2024, 25, 860–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willcockson, M.A.; Taylor, S.J.; Ghosh, S.; Healton, S.E.; Wheat, J.C.; Wilson, T.J.; Steidl, U.; Skoultchi, A.I. Runx1 promotes murine erythroid progenitor proliferation and inhibits differentiation by preventing Pu.1 downregulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 17841–17847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoyratty, T.E.; Ai, Z.; Ballesteros, I.; Eames, H.L.; Mathie, S.; Martín-Salamanca, S.; Wang, L.; Hemmings, A.; Willemsen, N.; von Werz, V.; et al. Distinct transcription factor networks control neutrophil-driven inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 2021, 22, 1093–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Zhao, P.; Luo, Q.; Wu, X.; Wang, Y.; Nan, Y.; Liu, S.; Gao, W.; Li, B.; Liu, Z.; et al. RUNX1-IT1 acts as a scaffold of STAT1 and NuRD complex to promote ROS-mediated NF-κB activation and ovarian cancer progression. Oncogene 2024, 43, 420–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagawa, M.; Shimabe, M.; Watanabe-Okochi, N.; Arai, S.; Yoshimi, A.; Shinohara, A.; Nishimoto, N.; Kataoka, K.; Sato, T.; Kumano, K.; et al. AML1/RUNX1 functions as a cytoplasmic attenuator of NF-κB signaling in the repression of myeloid tumors. Blood 2011, 118, 6626–6637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed-Inderbitzin, E.; Moreno-Miralles, I.; Vanden-Eynden, S.K.; Xie, J.; Lutterbach, B.; Durst-Goodwin, K.L.; Luce, K.S.; Irvin, B.J.; Cleary, M.L.; Brandt, S.J.; et al. RUNX1 associates with histone deacetylases and SUV39H1 to repress transcription. Oncogene 2006, 25, 5777–5786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwakarma, B.A.; Nguyen, N.; Makishima, H.; Hosono, N.; Gudmundsson, K.O.; Negi, V.; Oakley, K.; Han, Y.; Przychodzen, B.; Maciejewski, J.P.; et al. Runx1 repression by histone deacetylation is critical for Setbp1-induced mouse myeloid leukemia development. Leukemia 2016, 30, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herglotz, J.; Kuvardina, O.N.; Kolodziej, S.; Kumar, A.; Hussong, H.; Grez, M.; Lausen, J. Histone arginine methylation keeps RUNX1 target genes in an intermediate state. Oncogene 2013, 32, 2565–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frame, J.M.; Kubaczka, C.; Long, T.L.; Esain, V.; Soto, R.A.; Hachimi, M.; Jing, R.; Shwartz, A.; Goessling, W.; Daley, G.Q.; et al. Metabolic Regulation of Inflammasome Activity Controls Embryonic Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cell Production. Dev. Cell 2020, 55, 133–149.e136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Liu, X.; Ding, Y.; Tan, K.; Ni, W.; Ouyang, W.; Tang, J.; Ding, X.; Zhao, J.; Hao, Y.; et al. IL-6 coaxes cellular dedifferentiation as a pro-regenerative intermediate that contributes to pericardial ADSC-induced cardiac repair. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontecha-Barriuso, M.; Villar-Gomez, N.; Guerrero-Mauvecin, J.; Martinez-Moreno, J.M.; Carrasco, S.; Martin-Sanchez, D.; Rodríguez-Laguna, M.; Gómez, M.J.; Sanchez-Niño, M.D.; Ruiz-Ortega, M.; et al. Runt-related transcription factor 1 (RUNX1) is a mediator of acute kidney injury. J. Pathol. 2024, 264, 396–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Xiao, C.; Gu, J.; Chen, X.; Yuan, J.; Li, S.; Li, W.; Gao, D.; Li, L.; Liu, Y.; et al. 6-Gingerol ameliorates alveolar hypercoagulation and fibrinolytic inhibition in LPS-provoked ARDS via RUNX1/NF-κB signaling pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 128, 111459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Tang, C.Y.; Tang, H.N.; Wu, H.X.; Hu, N.; Li, L.; Zhou, H.D. Long Non-coding RNA 332443 Inhibits Preadipocyte Differentiation by Targeting Runx1 and p38-MAPK and ERK1/2-MAPK Signaling Pathways. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 663959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janta, S.; Pranweerapaiboon, K.; Vivithanaporn, P.; Plubrukarn, A.; Chairoungdua, A.; Prasertsuksri, P.; Apisawetakan, S.; Chaithirayanon, K. Holothurin A Inhibits RUNX1-Enhanced EMT in Metastasis Prostate Cancer via the Akt/JNK and P38 MAPK Signaling Pathway. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmore, H.A.B.; Amarnani, D.; O’Hare, M.; Delgado-Tirado, S.; Gonzalez-Buendia, L.; An, M.; Pedron, J.; Bushweller, J.H.; Arboleda-Velasquez, J.F.; Kim, L.A. TNF-α signaling regulates RUNX1 function in endothelial cells. FASEB J. 2021, 35, e21155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giambra, V.; Jenkins, C.R.; Wang, H.; Lam, S.H.; Shevchuk, O.O.; Nemirovsky, O.; Wai, C.; Gusscott, S.; Chiang, M.Y.; Aster, J.C.; et al. NOTCH1 promotes T cell leukemia-initiating activity by RUNX-mediated regulation of PKC-θ and reactive oxygen species. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 1693–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangpairoj, K.; Vivithanaporn, P.; Apisawetakan, S.; Chongthammakun, S.; Sobhon, P.; Chaithirayanon, K. RUNX1 Regulates Migration, Invasion, and Angiogenesis via p38 MAPK Pathway in Human Glioblastoma. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 37, 1243–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kantner, H.P.; Warsch, W.; Delogu, A.; Bauer, E.; Esterbauer, H.; Casanova, E.; Sexl, V.; Stoiber, D. ETV6/RUNX1 induces reactive oxygen species and drives the accumulation of DNA damage in B cells. Neoplasia 2013, 15, 1292–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satoh, Y.; Matsumura, I.; Tanaka, H.; Harada, H.; Harada, Y.; Matsui, K.; Shibata, M.; Mizuki, M.; Kanakura, Y. C-terminal mutation of RUNX1 attenuates the DNA-damage repair response in hematopoietic stem cells. Leukemia 2012, 26, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, Z.; Zeng, F.; Yan, J. RUNX1 Upregulation Causes Mitochondrial Dysfunction via Regulating the PI3K-Akt Pathway in iPSC from Patients with Down Syndrome. Mol. Cells 2023, 46, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Su, Y.; Yang, X.; Bai, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhuo, C.; Meng, Z. Gramine protects against pressure overload-induced pathological cardiac hypertrophy through Runx1-TGFBR1 signaling. Phytomedicine 2023, 114, 154779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, R.; Das, S.; Trahan, G.D.; Farriester, J.W.; Mullen, G.P.; Kyere-Davies, G.; Presby, D.M.; Houck, J.A.; Webb, P.G.; Dzieciatkowska, M.; et al. Neonatal intake of Omega-3 fatty acids enhances lipid oxidation in adipocyte precursors. iScience 2023, 26, 105750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, Y.; Nakanishi, Y.; Furuhata, E.; Nakada, K.I.; Maruyama, R.; Suzuki, H.; Suzuki, T. FLI1 is associated with regulation of DNA methylation and megakaryocytic differentiation in FPDMM caused by a RUNX1 transactivation domain mutation. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Song, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yao, Y.; Pan, T.; Qi, J.; Xia, L.; Wu, D.; Han, Y. Hypermethylation of DNA impairs megakaryogenesis in delayed platelet recovery after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eads3630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.; Wang, Q.; Li, C.C.; He, A. Single-cell joint profiling of multiple epigenetic proteins and gene transcription. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadi3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellissimo, D.C.; Chen, C.H.; Zhu, Q.; Bagga, S.; Lee, C.T.; He, B.; Wertheim, G.B.; Jordan, M.; Tan, K.; Worthen, G.S.; et al. Runx1 negatively regulates inflammatory cytokine production by neutrophils in response to Toll-like receptor signaling. Blood Adv. 2020, 4, 1145–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, L.F.; Mumau, M.D.; Li, Y.; Speck, N.A. MyD88-dependent TLR signaling oppositely regulates hematopoietic progenitor and stem cell formation in the embryo. Development 2022, 149, dev200025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Chen, Q.; Mei, L.; Wen, G.; An, W.; Zhou, X.; Niu, K.; Liu, C.; Ren, M.; Sun, K.; et al. Neutrophil elastase promotes neointimal hyperplasia by targeting toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-NF-κB signalling. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 178, 4048–4068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, H.; Zhang, Q.; Lv, Q.; Liu, H.; Wang, C.; Meng, F.; Guo, Y.; Pei, J.; Yu, C.; Tie, J.; et al. Chronic ethanol exposure induces hippocampal neuroinflammation and neuronal damage via the astrocytic RUNX1/TOLLIP/TLR3 pathway. Brain Behav. Immun. 2025, 130, 106081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kattih, B.; Boeckling, F.; Shumliakivska, M.; Tombor, L.; Rasper, T.; Schmitz, K.; Hoffmann, J.; Nicin, L.; Abplanalp, W.T.; Carstens, D.C.; et al. Single-nuclear transcriptome profiling identifies persistent fibroblast activation in hypertrophic and failing human hearts of patients with longstanding disease. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023, 119, 2550–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Yin, K.; Chen, L.; Chen, W.; Li, W.; Zhang, T.; Sun, Y.; Yuan, M.; Wang, H.; Song, Y.; et al. Lineage-specific regulatory changes in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy unraveled by single-nucleus RNA-seq and spatial transcriptomics. Cell Discov. 2023, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghagolzadeh, P.; Plaisance, I.; Bernasconi, R.; Treibel, T.A.; Pulido Quetglas, C.; Wyss, T.; Wigger, L.; Nemir, M.; Sarre, A.; Chouvardas, P.; et al. Assessment of the Cardiac Noncoding Transcriptome by Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Identifies FIXER, a Conserved Profibrogenic Long Noncoding RNA. Circulation 2023, 148, 778–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.W.; Rafiq, M.; Yuan, H.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Wu, J.; Wei, J.; Li, R.K.; Guo, H.; Yang, B.B. A Novel Protein NAB1-356 Encoded by circRNA circNAB1 Mitigates Atrial Fibrillation by Reducing Inflammation and Fibrosis. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2411959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, A.R.; Bugg, D.; Davis, J.; Saucerman, J.J. Network model integrated with multi-omic data predicts MBNL1 signals that drive myofibroblast activation. iScience 2023, 26, 106502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavillegrand, J.R.; Al-Rifai, R.; Thietart, S.; Guyon, T.; Vandestienne, M.; Cohen, R.; Duval, V.; Zhong, X.; Yen, D.; Ozturk, M.; et al. Alternating high-fat diet enhances atherosclerosis by neutrophil reprogramming. Nature 2024, 634, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, M.; Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Huang, T.; Li, X.; Ban, Y.; Li, Q.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Methyl-CpG-binding 2 K271 lactylation-mediated M2 macrophage polarization inhibits atherosclerosis. Theranostics 2024, 14, 4256–4277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, L.; Akbar, N.; Braithwaite, A.T.; Krausgruber, T.; Gallart-Ayala, H.; Bailey, J.; Corbin, A.L.; Khoyratty, T.E.; Chai, J.T.; Alkhalil, M.; et al. Hyperglycemia Induces Trained Immunity in Macrophages and Their Precursors and Promotes Atherosclerosis. Circulation 2021, 144, 961–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, S.; Gogiraju, R.; Rösch, M.; Kerstan, Y.; Beck, L.; Garbisch, J.; Saliba, A.E.; Gisterå, A.; Hermanns, H.M.; Boon, L.; et al. CD8(+) T Cells Drive Plaque Smooth Muscle Cell Dedifferentiation in Experimental Atherosclerosis. Arter. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2024, 44, 1852–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Tada, M.; Cai, Z.; Andhey, P.S.; Swain, A.; Miller, K.R.; Gilfillan, S.; Artyomov, M.N.; Takao, M.; Kakita, A.; et al. Human early-onset dementia caused by DAP12 deficiency reveals a unique signature of dysregulated microglia. Nat. Immunol. 2023, 24, 545–557, Erratum in Nat. Immunol. 2023, 24, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianevski, A.; Cámara-Quílez, M.; Wang, W.; Suganthan, R.; Hildrestrand, G.; Grini, J.V.; Døskeland, D.S.; Ye, J.; Bjørås, M. Early transcriptional responses reveal cell type-specific vulnerability and neuroprotective mechanisms in the neonatal ischemic hippocampus. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2025, 13, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; James, B.T.; Boix, C.A.; Park, Y.P.; Galani, K.; Victor, M.B.; Sun, N.; Hou, L.; Ho, L.L.; Mantero, J.; et al. Epigenomic dissection of Alzheimer’s disease pinpoints causal variants and reveals epigenome erosion. Cell 2023, 186, 4422–4437.e4421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Li, M.; Ji, Y.; Zhu, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, L.; Deng, C.; Cheng, Q.; Wang, W.; Shen, Y.; et al. Identification of Regulatory Factors and Prognostic Markers in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, Y.; Harada, Y.; Harada, H. Myeloid neoplasms and clonal hematopoiesis from the RUNX1 perspective. Leukemia 2022, 36, 1203–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venugopal, S.; Sekeres, M.A. Contemporary Management of Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Review. JAMA Oncol. 2024, 10, 1417–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homan, C.C.; Drazer, M.W.; Yu, K.; Lawrence, D.M.; Feng, J.; Arriola-Martinez, L.; Pozsgai, M.J.; McNeely, K.E.; Ha, T.; Venugopal, P.; et al. Somatic mutational landscape of hereditary hematopoietic malignancies caused by germline variants in RUNX1, GATA2, and DDX41. Blood Adv. 2023, 7, 6092–6107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, K.; Deuitch, N.; Merguerian, M.; Cunningham, L.; Davis, J.; Bresciani, E.; Diemer, J.; Andrews, E.; Young, A.; Donovan, F.; et al. Genomic landscape of patients with germline RUNX1 variants and familial platelet disorder with myeloid malignancy. Blood Adv. 2024, 8, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, M.P.T.; Versluis, J.; Valk, P.J.M.; Bierings, M.; Tamminga, R.Y.J.; Hooimeijer, L.H.; Döhner, K.; Gresele, P.; Tawana, K.; Langemeijer, S.M.C.; et al. Disease characteristics and outcomes of acute myeloid leukemia in germline RUNX1 deficiency (Familial Platelet Disorder with associated Myeloid Malignancy). Hemasphere 2025, 9, e70057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laragione, T.; Harris, C.; Gulko, P.S. Magnesium Supplementation Modifies Arthritis Synovial and Splenic Transcriptomic Signatures Including Ferroptosis and Cell Senescence Biological Pathways. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Mei, X.; Li, L.; Fang, P.; Guo, T.; Zhao, J. RUNX1 Ameliorates Rheumatoid Arthritis Progression through Epigenetic Inhibition of LRRC15. Mol. Cells 2023, 46, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Pi, C.; Chen, M.; Du, X.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, D.; Guo, Q.; Xie, J.; Zhou, X. Runx1 alleviates osteoarthritis progression in aging mice. J. Histotechnol. 2024, 47, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Cui, Y.; Yang, Y.; Guo, D.; Zhang, D.; Fan, Y.; Li, X.; Zou, J.; Xie, J. Runx1 protects against the pathological progression of osteoarthritis. Bone Res. 2021, 9, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Huang, C.; Bai, M.; Pi, C.; Zhang, D.; Xie, J. The roles of Runx1 in skeletal development and osteoarthritis: A concise review. Heliyon 2022, 8, e12656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Harbi, S.; Aljurf, M.; Mohty, M.; Almohareb, F.; Ahmed, S.O.A. An update on the molecular pathogenesis and potential therapeutic targeting of AML with t(8;21)(q22;q22.1);RUNX1-RUNX1T1. Blood Adv. 2020, 4, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- She, C.; Wu, C.; Guo, W.; Xie, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, W.; Xu, C.; Li, H.; Cao, P.; Yang, Y.; et al. Combination of RUNX1 inhibitor and gemcitabine mitigates chemo-resistance in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma by modulating BiP/PERK/eIF2α-axis-mediated endoplasmic reticulum stress. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 42, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksa, L.; Moisio, S.; Maqbool, K.; Kramer, R.; Nikkilä, A.; Jayasingha, B.; Mäkinen, A.; Foroughi-Asl, H.; Rounioja, S.; Suhonen, J.; et al. Genomic determinants of therapy response in ETV6::RUNX1 leukemia. Leukemia 2025, 39, 2125–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mill, C.P.; Fiskus, W.; DiNardo, C.D.; Birdwell, C.; Davis, J.A.; Kadia, T.M.; Takahashi, K.; Short, N.; Daver, N.; Ohanian, M.; et al. Effective therapy for AML with RUNX1 mutation by cotreatment with inhibitors of protein translation and BCL2. Blood 2022, 139, 907–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishikawa, Y.; Kawashima, N.; Atsuta, Y.; Sugiura, I.; Sawa, M.; Dobashi, N.; Yokoyama, H.; Doki, N.; Tomita, A.; Kiguchi, T.; et al. Prospective evaluation of prognostic impact of KIT mutations on acute myeloid leukemia with RUNX1-RUNX1T1 and CBFB-MYH11. Blood Adv. 2020, 4, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, C.N.; Bledsoe, J.R.; Grzywacz, B.; Beckman, A.; Bonner, M.; Eichler, F.S.; Kühl, J.S.; Harris, M.H.; Slauson, S.; Colvin, R.A.; et al. Hematologic Cancer after Gene Therapy for Cerebral Adrenoleukodystrophy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 1287–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumbo, C.; Tarantini, F.; Parciante, E.; Anelli, L.; Zagaria, A.; Biondi, G.; Caratozzolo, M.F.; Orsini, P.; Coccaro, N.; Tota, G.; et al. RUNX1A isoform is overexpressed in acute myeloid leukemia and is associated with FLT3 internal tandem duplications. Cancer Gene Ther. 2025, 32, 963–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Lan, M.; Yuan, Z.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Han, C.; Ai, D.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Regulation of blood pressure by METTL3 via RUNX1b-eNOS pathway in endothelial cells in mice. Cardiovasc. Res. 2025, 121, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Sun, L.; Jin, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, H.; Liang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Han, X.; Liang, J.; Liu, X.; et al. Runt-Related Transcription Factor 1 Regulates LPS-Induced Acute Lung Injury via NF-κB Signaling. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2017, 57, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand-Philippe, M.; Ruddell, R.G.; Arthur, M.J.; Thomas, J.; Mungalsingh, N.; Mann, D.A. Regulation of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 gene transcription by RUNX1 and RUNX2. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 24530–24539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, F.C.; Shapiro, M.J.; Dash, B.; Chen, C.C.; Constans, M.M.; Chung, J.Y.; Romero Arocha, S.R.; Belmonte, P.J.; Chen, M.W.; McWilliams, D.C.; et al. An Essential Role for the Transcription Factor Runx1 in T Cell Maturation. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 23533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, J.E.; Valli, E.; Milazzo, G.; Mayoh, C.; Gifford, A.J.; Fletcher, J.I.; Xue, C.; Jayatilleke, N.; Salehzadeh, F.; Gamble, L.D.; et al. The transcriptional co-repressor Runx1t1 is essential for MYCN-driven neuroblastoma tumorigenesis. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, L.; Finckbeiner, S.; Hyde, R.K.; Southall, N.; Marugan, J.; Yedavalli, V.R.; Dehdashti, S.J.; Reinhold, W.C.; Alemu, L.; Zhao, L.; et al. Identification of benzodiazepine Ro5-3335 as an inhibitor of CBF leukemia through quantitative high throughput screen against RUNX1-CBFβ interaction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 14592–14597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, E.M.; Pereira, M.; So, E.Y.; Wu, K.Q.; Del Tatto, M.; Wen, S.; Dooner, M.S.; Dubielecka, P.M.; Reginato, A.M.; Ventetuolo, C.E.; et al. Targeting RUNX1 as a novel treatment modality for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022, 118, 3211–3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perzolli, A.; Steinebach, C.; Krönke, J.; Gütschow, M.; Zwaan, C.M.; Barneh, F.; Heidenreich, O. PROTAC-Mediated GSPT1 Degradation Impairs the Expression of Fusion Genes in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancers 2025, 17, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, D.M.; Rohilla, S.; Kaur, I.; Siddiqui, H.; Rawal, P.; Juneja, P.; Kumar, V.; Kumari, A.; Naidu, V.G.M.; Ramakrishna, S.; et al. Immunonano-Lipocarrier-Mediated Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cell-Specific RUNX1 Inhibition Impedes Immune Cell Infiltration and Hepatic Inflammation in Murine Model of NASH. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hare, M.; Miller, W.P.; Arevalo-Alquichire, S.; Amarnani, D.; Apryani, E.; Perez-Corredor, P.; Marino, C.; Shu, D.Y.; Vanderleest, T.E.; Muriel-Torres, A.; et al. An mRNA-encoded dominant-negative inhibitor of transcription factor RUNX1 suppresses vitreoretinal disease in experimental models. Sci. Transl. Med. 2024, 16, eadh0994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.Y.; Li, J.F.; Zhu, Y.M.; Lin, X.J.; Wen, L.J.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, Y.L.; Zhao, M.; Fang, H.; Wang, S.Y.; et al. Transcriptome-based molecular subtypes and differentiation hierarchies improve the classification framework of acute myeloid leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2211429119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurnari, C.; Pagliuca, S.; Prata, P.H.; Galimard, J.E.; Catto, L.F.B.; Larcher, L.; Sebert, M.; Allain, V.; Patel, B.J.; Durmaz, A.; et al. Clinical and Molecular Determinants of Clonal Evolution in Aplastic Anemia and Paroxysmal Nocturnal Hemoglobinuria. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.H.; Langlois, S.; Meloche, C.; Caron, M.; Saint-Onge, P.; Rouette, A.; Bataille, A.R.; Jimenez-Cortes, C.; Sontag, T.; Bittencourt, H.; et al. Whole-transcriptome analysis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A report from the DFCI ALL Consortium Protocol 16-001. Blood Adv. 2022, 6, 1329–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Xu, B.; Wu, M.; Zhan, M.; Wang, S.; Lu, H. DNMT1 recruits RUNX1 and represses FOXO1 transcription to inhibit anti-inflammatory activity of regulatory T cells and augments sepsis-induced lung injury. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2025, 41, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Hare, M.; Amarnani, D.; Whitmore, H.A.B.; An, M.; Marino, C.; Ramos, L.; Delgado-Tirado, S.; Hu, X.; Chmielewska, N.; Chandrahas, A.; et al. Targeting Runt-Related Transcription Factor 1 Prevents Pulmonary Fibrosis and Reduces Expression of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Host Mediators. Am. J. Pathol. 2021, 191, 1193–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Pan, Q.; Zhang, L.; Xia, H.; Liao, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, N.; Xie, Q.; Liao, M.; Tan, Y.; et al. Runt-related transcription factor-1 ameliorates bile acid-induced hepatic inflammation in cholestasis through JAK/STAT3 signaling. Hepatology 2023, 77, 1866–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Chen, J.; Yu, X.; Li, Z.; Chen, J.; Fang, D.; Lin, X.; Tu, H.; Xu, X.; Yang, S.; et al. Single-cell analysis identifies RETN+ monocyte-derived Resistin as a therapeutic target in hepatitis B virus-related acute-on-chronic liver failure. Gut 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boros, É.; Hegedűs, Z.; Kellermayer, Z.; Balogh, P.; Nagy, I. Global alteration of colonic microRNAome landscape associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 991346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.L.; Zhang, S.B.; Xu, S.F.; Gu, X.N.; Wu, Z.Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Ji, L.L. TSG attenuated NAFLD and facilitated weight loss in HFD-fed mice via activating the RUNX1/FGF21 signaling axis. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2025, 46, 2723–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Gan, C.; Zhang, R.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, W.; Liu, L.; Shang, J.; Zhao, Q. TRAF5 regulates intestinal mucosal Th1/Th17 cell immune responses via Runx1 in colitis mice. Immunology 2023, 170, 495–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadhosseini, M.; Enright, T.; Duvall, A.; Chitsazan, A.; Lin, H.Y.; Ors, A.; Davis, B.A.; Nikolova, O.; Bresciani, E.; Diemer, J.; et al. Targeting the CD74 signaling axis suppresses inflammation and rescues defective hematopoiesis in RUNX1-familial platelet disorder. Sci. Transl. Med. 2025, 17, eadn9832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitch, B.A.; Zhou, M.; Situ, J.; Surianarayanan, S.; Reeves, M.Q.; Hermiston, M.L.; Wiemels, J.L.; Kogan, S.C. Decreased IL-10 accelerates B-cell leukemia/lymphoma in a mouse model of pediatric lymphoid leukemia. Blood Adv. 2022, 6, 854–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddell, A.; McBride, M.; Braun, T.; Nicklin, S.A.; Cameron, E.; Loughrey, C.M.; Martin, T.P. RUNX1: An emerging therapeutic target for cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc. Res. 2020, 116, 1410–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, D.; Wang, T.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Shao, J.; Yang, M.; Huang, C.; Zuo, S.; Wu, N. PRMT1 inhibition enhances the cardioprotective effect of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells against myocardial infarction through RUNX1. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2025, 16, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, T.; Zhao, S.; Luo, S.; Chen, C.; Liu, X.; Wu, X.; Sun, Z.; Cao, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; et al. SLC44A2 regulates vascular smooth muscle cell phenotypic switching and aortic aneurysm. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 134, e173690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertran, L.; Eigbefoh-Addeh, A.; Portillo-Carrasquer, M.; Barrientos-Riosalido, A.; Binetti, J.; Aguilar, C.; Ugarte Chicote, J.; Bartra, H.; Artigas, L.; Coma, M.; et al. Identification of the Potential Molecular Mechanisms Linking RUNX1 Activity with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease, by Means of Systems Biology. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcher, A.B.; Bendixen, S.M.; Terkelsen, M.K.; Hohmann, S.S.; Hansen, M.H.; Larsen, B.D.; Mandrup, S.; Dimke, H.; Detlefsen, S.; Ravnskjaer, K. Transcriptional regulation of Hepatic Stellate Cell activation in NASH. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wang, B.; Gu, Y.; Yu, H.; Yang, W.; Ren, X.; Qian, F.; Zhao, X.; Xiao, Y.; et al. Inhibition of EZH2 ameliorates bacteria-induced liver injury by repressing RUNX1 in dendritic cells. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Jiang, W.I.; Arkelius, K.; Swanson, R.A.; Ma, D.K.; Singhal, N.S. PATJ regulates cell stress responses and vascular remodeling post-stroke. Redox Biol. 2025, 85, 103709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, X.; Chowdhury, I.H.; Jie, Z.; Choudhuri, S.; Garg, N.J. Origin of Monocytes/Macrophages Contributing to Chronic Inflammation in Chagas Disease: SIRT1 Inhibition of FAK-NFκB-Dependent Proliferation and Proinflammatory Activation of Macrophages. Cells 2019, 9, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zolotarenko, A.; Chekalin, E.; Mesentsev, A.; Kiseleva, L.; Gribanova, E.; Mehta, R.; Baranova, A.; Tatarinova, T.V.; Piruzian, E.S.; Bruskin, S. Integrated computational approach to the analysis of RNA-seq data reveals new transcriptional regulators of psoriasis. Exp. Mol. Med. 2016, 48, e268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, C.; Kojo, S.; Yamashita, M.; Moro, K.; Lacaud, G.; Shiroguchi, K.; Taniuchi, I.; Ebihara, T. Runx/Cbfβ complexes protect group 2 innate lymphoid cells from exhausted-like hyporesponsiveness during allergic airway inflammation. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Isoform | Structural Features | Major Functions | Characteristic Roles in Disease Contexts |

|---|---|---|---|

| RUNX1a | Lacks transcriptional activation domain |

| Enhances progenitor expansion and inflammatory sensitivity (e.g., CHIP, myeloid bias) |

| RUNX1b/c | Possesses a complete transcriptional activation domain |

| Promotes chronic inflammation and fibrosis/senescence (cardiac, renal, and age-related tissue pathologies) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, K.; Wang, S. The Dual Role of RUNX1 in Inflammation-Driven Age-Related Diseases: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Translation. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2999. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122999

Chen K, Wang S. The Dual Role of RUNX1 in Inflammation-Driven Age-Related Diseases: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Translation. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):2999. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122999

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Kexin, and Si Wang. 2025. "The Dual Role of RUNX1 in Inflammation-Driven Age-Related Diseases: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Translation" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 2999. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122999

APA StyleChen, K., & Wang, S. (2025). The Dual Role of RUNX1 in Inflammation-Driven Age-Related Diseases: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Translation. Biomedicines, 13(12), 2999. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122999