In this study, transcriptomic analysis revealed that distinct gene expression profiles differed in the PBMCs of patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis compared to those of HCs. Enrichment analyses indicated the upregulation of various terms and pathways associated with granuloma formation in sarcoidosis. These findings provide a more detailed understanding of the pathobiological mechanisms underlying granuloma formation in pulmonary sarcoidosis. Furthermore, this study demonstrates the differences in the transcriptome features of PBMCs in pulmonary sarcoidosis between patients with and without EPL, suggesting that gene expressions in PBMCs may reflect the clinical features of sarcoidosis involving multiple organs.

4.1. Patients with Pulmonary Sarcoidosis vs. Healthy Controls (HCs)

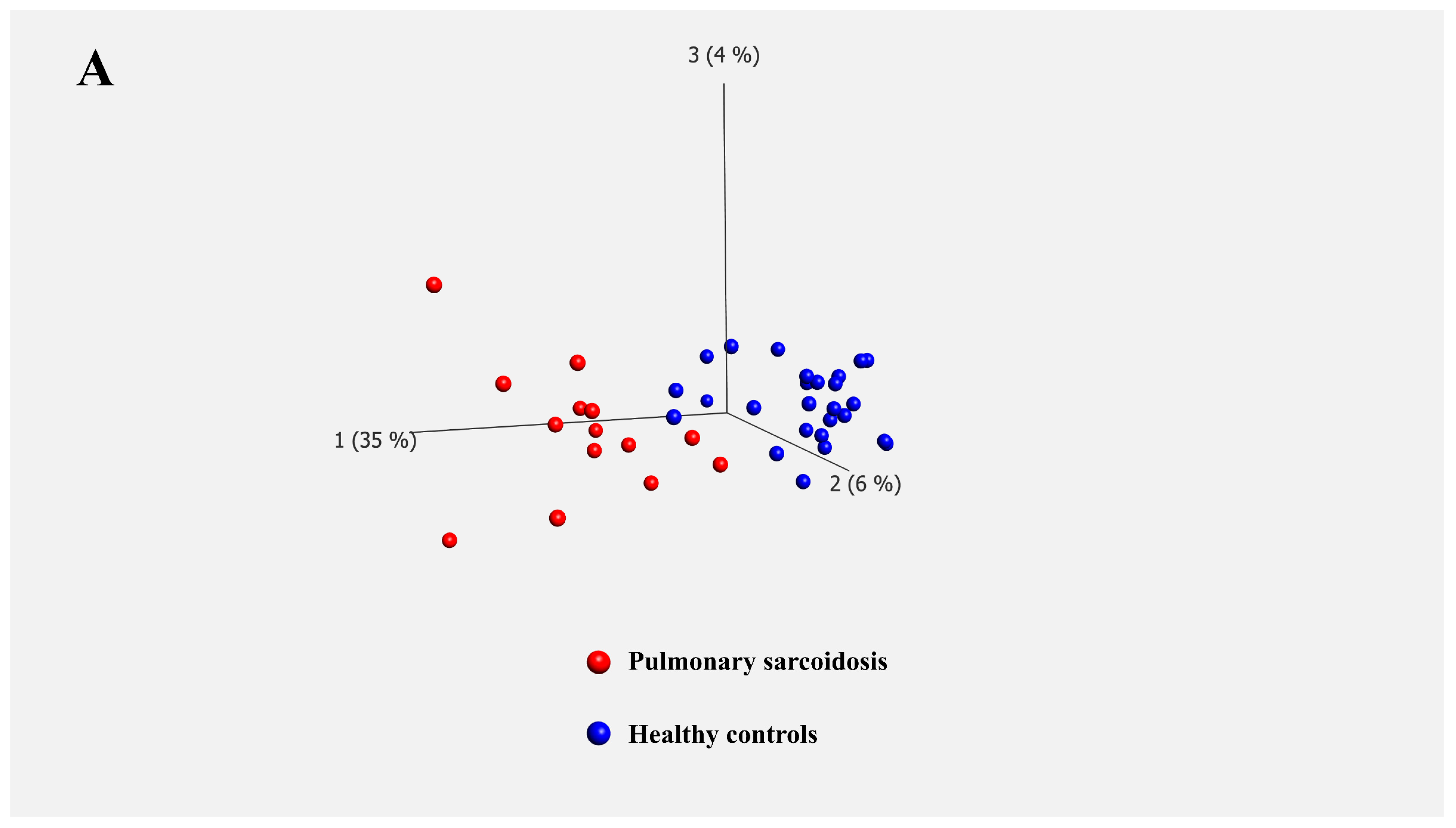

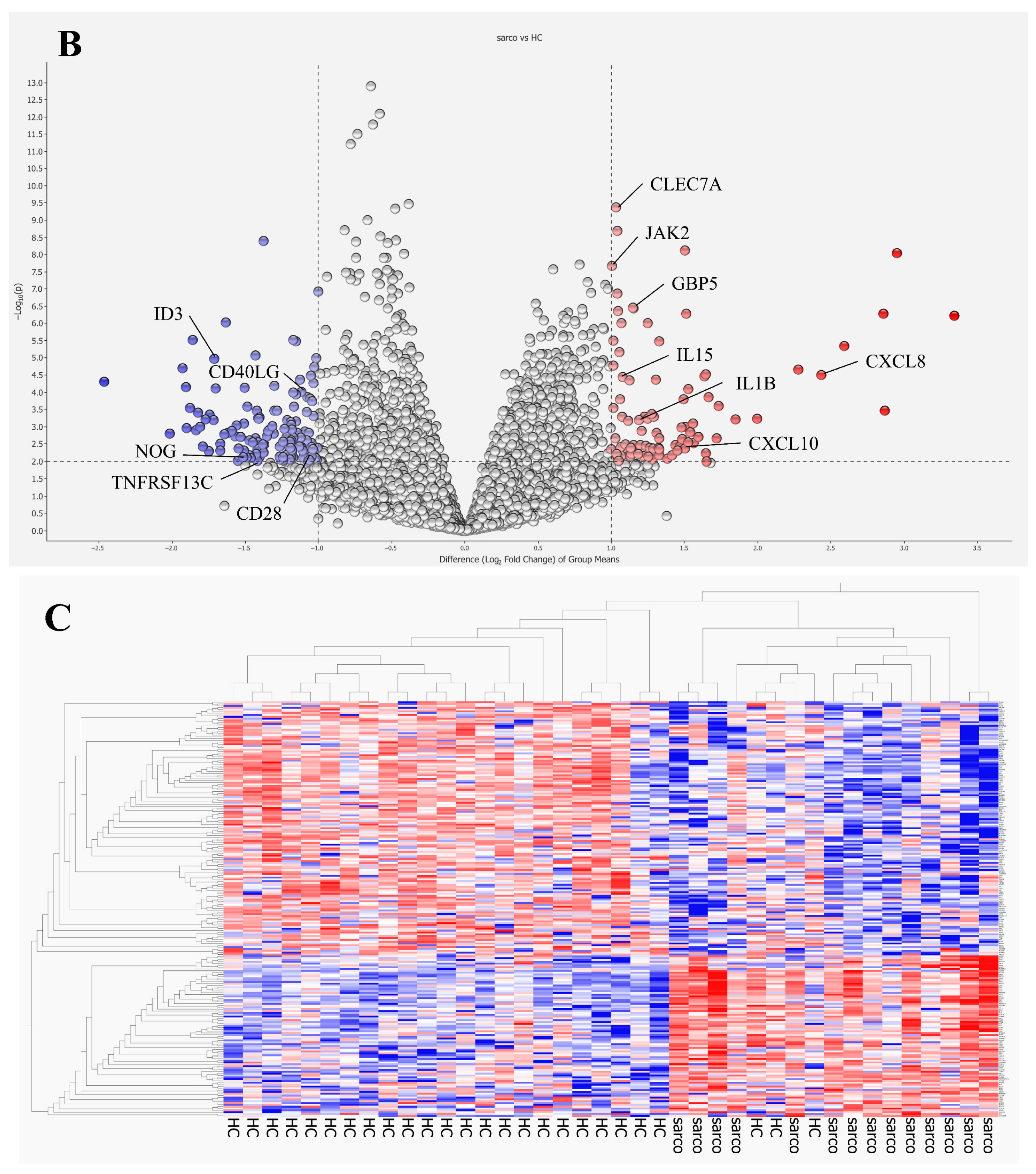

Transcriptomic analysis of bulk PBMCs identified 227 differentially expressed genes between patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis and HCs. GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses highlighted numerous immunological responses, inflammatory cytokine production pathways, and responses to external stimuli (

Table 4 and

Table 5). These results supported well-established pathobiological mechanisms underlying sarcoidosis. Our previous study indicated the differential transcriptomic features of PBMCs in pulmonary sarcoidosis could be associated with the mechanism of sarcoidosis; however, this study had several limitations, notably a statistically significant age disparity between groups and a small sample size [

9]. Therefore, we used a larger cohort where no significant differences were observed in age and sex between the pulmonary sarcoidosis and HCs to verify the findings in our previous study. Although still exploratory, the age/sex matching and the larger sample size in the current study provide more confidence in the observed gene expression signatures.

First, our analysis revealed that pathways related to responses to external stimuli were upregulated in patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis. GO terms such as “response to molecules of bacterial origin”, “positive regulation of response to external stimuli,” and “response to lipopolysaccharide,” were enriched. Lipopolysaccharide, a component of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, triggers innate immune responses primarily through Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4), leading to the production of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, and IL-8 in monocytes and macrophages—key mediators involved in granuloma formation in sarcoidosis [

13].

Furthermore, the “Toll-like receptor signaling pathway” was identified in the KEGG pathway analysis. TLR-2 and TLR-4 expression in blood mononuclear cells is significantly higher in patients with sarcoidosis than that in HCs [

14]. Similarly, the “nucleotide oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptor signaling pathway” was enriched, highlighting the role of NOD-like receptors (NLRs) in activating transcriptional factors such as nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), activator protein-1 (AP-1) and interferon regulator factor 5 (IRF5) that drive pro-inflammatory cytokine production [

15]. NLRs comprise cytosolic proteins known as nucleotide-binding oligomerization domains (NODs), including NOD1 and NOD2. Notably, hyperfunction mutations in NOD2 cause Blau syndrome and early-onset sarcoidosis, which are systemic granulomatous diseases [

16]. Additionally, the “C-type lectin receptor signaling pathway” was identified with the C-type lectin domain family 7 member A (

CLEC7A).

CLEC7A is expressed in monocytes, macrophages, neutrophils and dendritic cells, and is involved in antifungal immunity [

17].

CLEC7A activation induces cytokine release, such as IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-23, favoring Th17 cell differentiation, and IL-12, driving IFN-γ production by Th1 and NKT cells [

18].

Gene Ontology and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses also highlighted terms related to phagocytosis; specifically, “positive regulation of phagocytosis” and “phagosome” were listed. Phagocytosis is a cellular process that engulfs and clears microbes and apoptotic cells, producing inflammatory cytokines, and antigen presentation, particularly by macrophages, monocytes and dendritic cells. These cells initiate the differentiation of Th1 and 17 cells or produce IFN-γ, potentially contributing to granuloma formation in pulmonary sarcoidosis [

19]. Collectively, these results suggest that pulmonary sarcoidosis involves an immunological response to unidentified external antigens.

Several pathways involved in cytokine regulation were also enriched, including “positive regulation of IL-1β production”, “positive regulation of IL-6 production,” and “TNF-α signaling pathway”. These cytokines are produced by alveolar macrophages in sarcoidosis even in unstimulated conditions [

20]. The elevated expression of these cytokines in PBMCs suggests their potential role in the systemic granulomatous mechanisms of sarcoidosis.

Pathways related to Th17 were also enriched, including “positive regulation of Th17 type immune response,” “positive regulation of IL-17 production,” “IL-17 signaling pathway,” and “Th17 cell differentiation.” Th17 cells, which differentiate from CD4

+ T cells under IL-6 and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) stimulation, are implicated in granuloma formation [

21]. However, Th17.1 cells, known for producing high amounts of IFN-γ, are considered more crucial for maintaining granuloma [

22]. Interestingly, Th17.1 cells are enriched in sarcoidosis lesions but are less prevalent in the peripheral blood [

23], possibly explaining why terms related to Th17.1 cells were not enriched in PBMCs in this study.

Finally, the “cellular response to type II interferons” and the “positive regulation of type II interferon production” were identified. IFN-γ, produced by natural killer (NK) cells, Th1 cells, Th17.1 cells and CD8

+ T cells, activates macrophages, promoting TNF-α and IL-12 production by macrophages [

24]. Macrophages produce chemokine ligands such as monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), C-C motif chemokine ligand 20 (CCL20), CXCL10 and CXCL16 under stimulation of both TNF-α and IFN-γ, thereby attracting Th1/17 cells, monocytes, regulatory T and B cells to inflammation sites [

19]. The upregulation of

CXCL10, associated with “regulation of monocyte chemotaxis”, aligns with previous findings on the roles of IFN-γ in granuloma formation [

1].

4.2. Pulmonary Sarcoidosis with vs. Without Extrapulmonary Lesions (EPL)

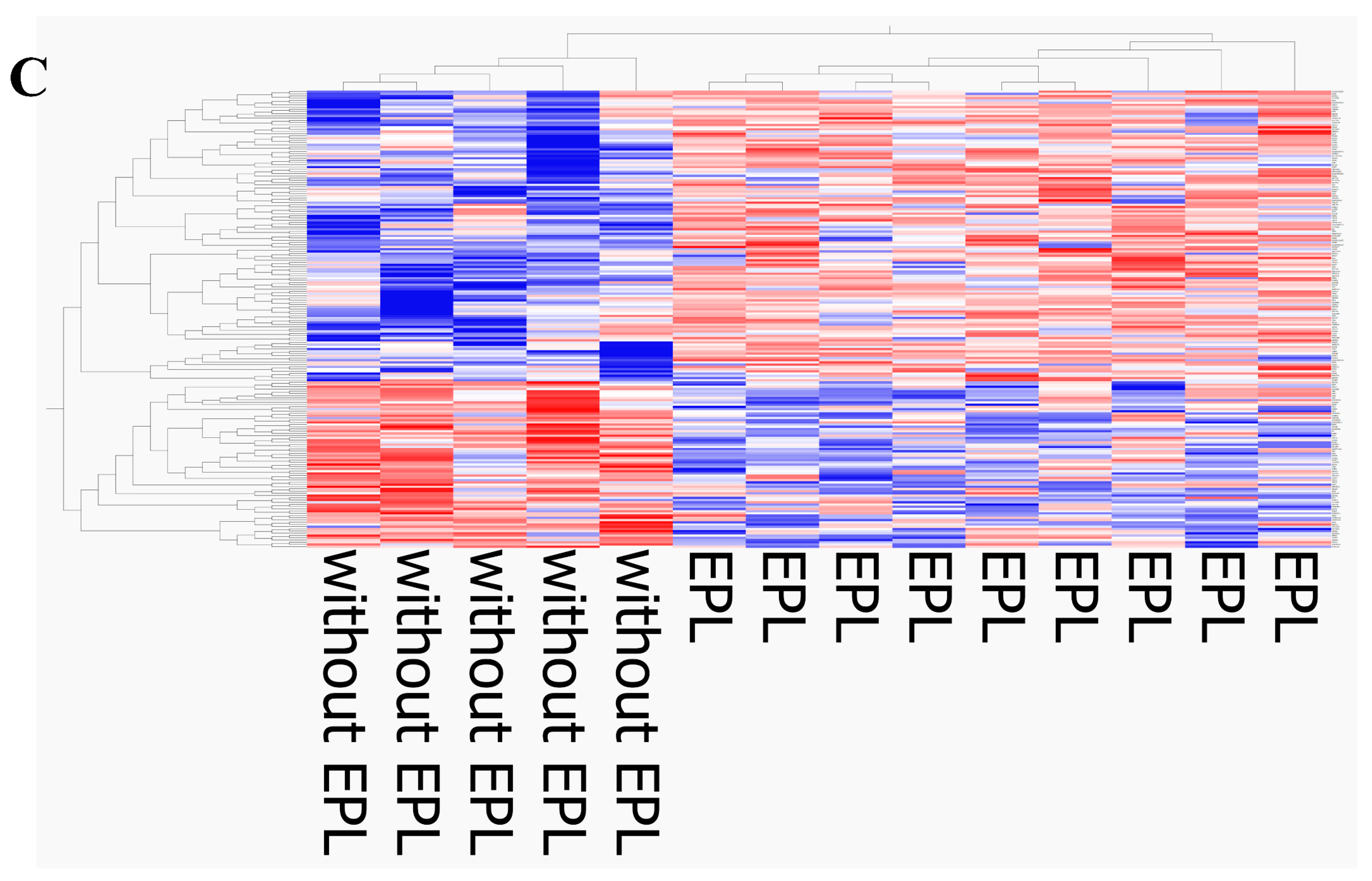

The current results revealed differential transcriptomic features of PBMCs in pulmonary sarcoidosis between patients with and without EPL, although our previous study found no transcriptomic differences between the two groups, probably due to a small sample size [

9]. The current analysis successfully identified 206 DEGs associated with EPL. This finding identified a novel

INFG/

INFLR1 signature. Therefore, this study provides the first transcriptomic evidence differentiating systemic EPL sarcoidosis from isolated pulmonary disease. The present study has shown the upregulation of

IFNG and

IFNLR1, included in the “interferon-mediated signaling pathway,” in patients with sarcoidosis with EPL manifestation, suggesting their potential role in granuloma progression to multiple organs. Interferon gamma (

IFNG) is the gene that encodes IFN-γ, a member of the type II interferon family and a key cytokine in sarcoidosis pathogenesis. Single-cell analyses of granulomas in skin sarcoidosis have revealed that

IFNG is upregulated in helper T cells, including Th17.1 cells, but not in macrophages [

25]. Th17.1 cells are more prevalent in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid than in the peripheral blood from patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis [

23,

26]. Our study suggests that the upregulation of

IFNG in the PBMCs may closely reflect the activities of systemic granuloma formation and contribute to EPL during sarcoidosis.

IFNLR1, which belongs to the class II cytokine receptor family, forms a receptor complex with IL-10 receptor 2 (IL10R2). Its ligands are known as IL-28A, IL-28B, and IL-29, categorized as type III interferons (IFN-λ) [

27]. The

IFNLR1 expression has been detected in various immune cells, including macrophages, dendritic cells, neutrophils, and B and T lymphocytes, whereas minimal to no expression has been observed in monocytes and NK cells [

28,

29]. IFN-λ is secreted by mucosal epithelial cells in response to viral infection and regulates inflammatory responses [

30]. The IFN-λ signaling pathway plays a pivotal role in guiding the host response to numerous pathogens encountered at mucosal surfaces [

31]. Furthermore, a recent study on macaque monkeys infected with

Mycobacterium tuberculosis revealed that IFN-λ and IFNRL1 are expressed in lung granulomas, and IFN-λ signaling is partly driven by TLR2 ligation [

32]. These findings indicate that IFN-λ may be closely associated with granuloma formation and maintenance.

IFNG and IFNRL1 are included in several GO terms: “positive regulation of IL-23 production,” “regulation of IL-6 production,” and “interferon-mediated signal pathway”. IL-6 induces Th1 and Th17 cell differentiation, and the survival and proliferation of Th17 cells depend on IL-23. These cytokines play important roles in granuloma development by activating Th1 and Th17 cells.

In sarcoidosis, the

IFNLR1 functions and regulatory mechanisms are yet to be fully elucidated. However, our study suggests that

IFNLR1 upregulation in the PBMCs of patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis with EPL may relate to EPL development through PBMC recruitment to local lesions via circulation. IFN-λ may promote Th1 polarization in T cells, thereby enhancing macrophage activation and contributing to granuloma formation [

32]. Taken together, IFNLR1 upregulation in the PBMCs suggests that IFN-λ signaling could drive granuloma formation not only in the lung but also in multiple organs.

Meanwhile, the “TNF signaling pathway” and “IL-17 signaling pathway” were listed in the KEGG pathway analysis with downregulated genes, including

MMP9,

CXCL10, and

SOCS3.

SOCS3 is a negative regulator of the Janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of the transcription (JAK/STAT) pathway, especially in STAT3, which activates the IL-23 signaling pathway. In contrast, the loss of

SOCS3 leads to enhanced Th17 generation [

33]. Furthermore, Th17.1 cells, which produce both IL-17 and IFN-γ, display reduced

SOCS3 expression compared to that of Th17 or Th1 cells [

34]. Therefore,

SOCS3 downregulation may enhance Th17.1 polarization.

MMP9 degrades the extracellular matrix and promotes fibrosis [

25]. Its expression is stronger in later-stage granulomas with less lymphocyte infiltration, suggesting that MMP-9 promotes granulomatous fibrosis in the chronic sarcoidosis stage [

35]. Furthermore, a lower number of collagen fibers and a lower density of elastic fibers are observed in extrapulmonary granulomas compared with those in pulmonary granulomas in sarcoidosis [

36]. Therefore, the downregulation of

MMP9 in the PBMCs from patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis with EPL might indicate the different pathobiological features between extrapulmonary and pulmonary sarcoidosis.

Cardiac sarcoidosis is a clinically poor prognostic factor for patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis. Therefore, we additionally compared the transcriptomes of PBMCs between patients with and without cardiac involvement; however, these results should be considered exploratory rather than conclusive, due to the limited statistical power of our analysis. The results indicated that genes related to cardiac muscle function, including myomesin 2 (MYOM2), adenylate cyclase type 2 (ADCY2), ADCY5, and NOS (including NOS1 and NOS2), might be upregulated in PBMCs from patients with cardiac involvement. This upregulation led to the enrichment of several GO terms and KEGG pathways.

Regarding the upregulation of

NOS2 in PBMCs, NOS2 is recognized as a marker of M1 macrophages, which exhibit pro-inflammatory functions induced by LPS or IFN-γ and also generate NO from L-arginine to prevent bacterial growth in inflammation sites including granulomas [

37]. Although the mechanisms linking NOS2 and cardiac involvement remain unclear, the upregulation of NOS2 in sarcoidosis may be related to the promotion of granuloma formation in inflammatory states. These results were obtained from an exploratory data analysis using a limited sample size; validation studies with larger sample sizes are essential.

This study has several limitations. First, it remains unclear whether the observed changes in PBMC gene expression are a consequence of the disease or if they actively contribute to the disease development. Second, although the DEGs identified in this study could provide insights into the pathological mechanisms of pulmonary sarcoidosis with EPL, these findings have not been confirmed by assessing the corresponding gene expression or protein levels in PBMCs using qPCR or cytokine quantification, nor have they been visualized by using some pathway analysis tools. Additionally, the false discovery rate of the q-value should be taken into consideration to interpret the

p-values. Furthermore, if cell sorting has been performed prior to the analysis or single-cell RNA sequencing has been carried out, more specific DEGs for each cell type would likely have been detected. Validation of the transcriptomic data would enhance the robustness of the conclusions of this study. Third, this study was conducted at a single center in Japan with a small, ethnically homogenous cohort (although we matched age and sex between groups). Because ethnic differences in sarcoidosis phenotypes and genetic factors have been reported [

38], transcriptomic signatures of sarcoidosis may also vary across ethnic groups. Therefore, the generalizability of our results to other populations is limited, and validation studies in more diverse cohorts are warranted. Finally, transcriptomic features of PBMCs from the EPL group may be heterogeneous due to the diversity of extrapulmonary lesions. It is highly likely that the observed gene expression patterns are not uniform across all organ manifestations. Accordingly, studies with a larger stratified cohort would provide clearer organ-specific gene expression profiles. Furthermore, although five patients were classified as without EPL, it remains possible that they had subclinical extrapulmonary involvement that could not be detected even by specialist evaluation.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that the gene expression profiles in PBMCs differ between patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis and age and sex-matched HCs. Various GO terms and KEGG pathways associated with granuloma formation were identified, strengthening our understanding of the underlying mechanisms in patients with sarcoidosis. Furthermore, the differential transcriptome features in PBMCs from patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis between patients with and without EPL were demonstrated, particularly the upregulations of IFNG and IFNLR1. The upregulation of these genes might be related to EPL development and could serve as potential therapeutic targets for sarcoidosis.