1. Introduction

This article presents the authors’ perspective on advancing research in hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) and related vascular disorders. It underscores patient partnership and cross-disease collaboration as essential for research progress, pointing out that these topics warrant greater focus within the field of rare diseases. The opinion is based on discussions during a recently held scientific symposium and on the current literature. This work is neither a systematic nor narrative review; it does not follow a systematic methodology. Furthermore, the authors would like to explicitly state that no financial support or promotional interests influenced the authors’ opinion. The aim is to provide an overview that reflects ongoing discussions and emerging opportunities within the complex field of rare vascular disorders, specifically HHT. To the best of our knowledge, no existing opinion article explicitly examines the role of cross-disease collaboration in rare vascular disorders or highlights how patient-organised scientific meetings can accelerate progress in this field. This article aims to address that gap.

2. Background: HHT

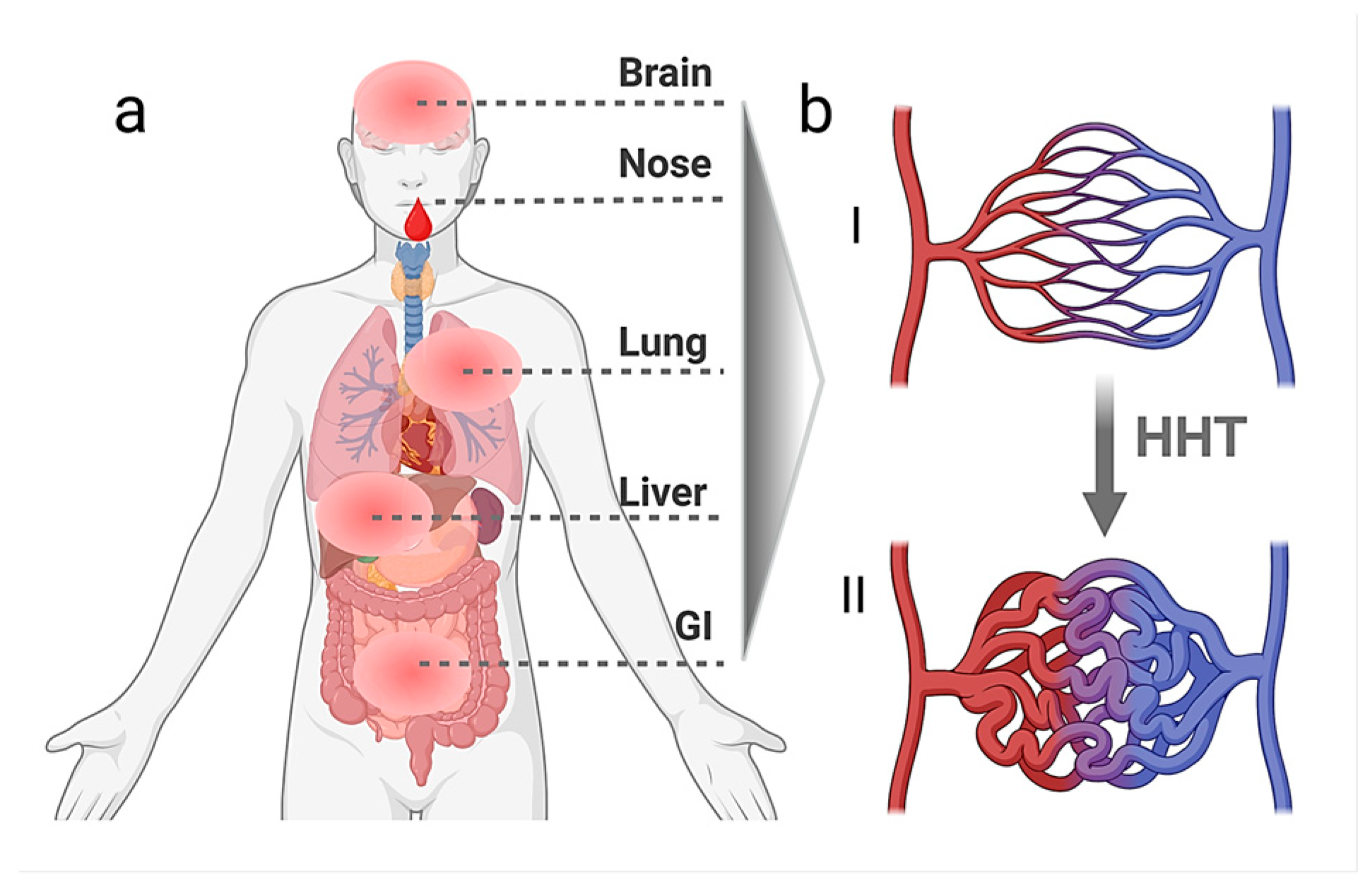

Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), also known as Rendu–Osler–Weber syndrome or Morbus Osler, is an autosomal-dominant, inherited disorder of the vascular connective tissue [

1,

2,

3]. It is characterised by the formation of telangiectases and vascular malformations (VMs) in characteristic mucocutaneous sites and internal organs such as the liver, the lungs, the gastrointestinal organs, and the brain (

Figure 1) [

4]. To date, little is known about the complex molecular pathomechanisms causing this disease and the cell types that participate in the disease’s initiation and manifestation. The main genes identified thus far encode the cell surface receptors of the TGF-β (Transforming Growth Factor β) superfamily, the Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP) pathway co-receptor Endoglin (

ENG) [

5], BMP type I receptor ALK1 (

ACVRL1) [

6], and the downstream effector protein Smad4 [

7].

Recurrent, spontaneous, and often severe epistaxis represents one of the earliest and most prominent clinical manifestations, typically accompanied by (muco-)cutaneous telangiectases. To this date, the Curaçao criteria are the consensus clinical diagnostic criteria for HHT, listed in

Table 1. HHT is considered definite when three or four Curaçao criteria are met, possible with exactly two, and unlikely with one or none [

8].

Chronic and acute complications in HHT can result from either arteriovenous shunting or bleeding. The rupture of cerebral VMs can cause haemorrhagic strokes, whereas rupture of nasal or intestinal lesions leads to recurrent epistaxis or gastrointestinal bleeding [

4,

9]. This often causes iron deficiency and anaemia, symptoms that require appropriate blood management and iron-replacement strategies to improve patients’ life quality [

10].

When present in the lungs, pulmonary arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) create right-to-left shunting with impaired filtration function of lung vessels, causing brain abscesses and ischaemic strokes. As these complications are directly life-threatening, pulmonary screening is recommended for all individuals with a definite or possible HHT diagnosis [

10,

11].

VMs located in the liver—resulting in right-to-left hepatic shunting—can drastically increase cardiac output. Over time, this persistently hyperdynamic circulatory state may exceed the heart’s compensatory capacity, ultimately leading to high-output cardiac failure [

12,

13]. Furthermore, hepatoportal shunting can lead to portal hypertension, and portohepatic shunting might lead to encephalopathy [

13,

14]. In addition, all vascular shunts can cause blood steal, whereby surrounding tissues receive reduced oxygen supply as blood preferentially flows through the low-resistance channels of the VM.

To date, no causal therapy for HHT exists and treatment options for the individual symptoms are recommended in the Second International Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of HHT [

10]. Hence, there is still much to learn about the molecular mechanisms and the clinical symptoms of HHT. Combining expertise from clinicians, various research fields, and patient’s experiences may help enhance understandings of HHT pathogenesis. These perspectives can be brought together and facilitated, for example, at patient meetings accompanied by a diverse set of scientific and medical stakeholders.

3. Rationale: The Added Value of Partnership

Scientific networks such as VASCERN, the European Reference Network for rare multisystemic vascular diseases, and the internationally active CureHHT organisation, serve as the overarching framework that connects and strengthens the global HHT community. They coordinate expertise, foster collaboration, and support research efforts across the HHT field.

Multi-stakeholder meetings like the Second Scientific Symposium hosted by the German HHT self-help group (Morbus Osler Selbsthilfe e.V.) in May 2025 reveal knowledge gaps on multiple sides. Clinicians, for instance, can explain acute bleeding management for newly diagnosed and unexperienced patients. They can demonstrate, e.g., nasal-packing options such as pneumatic balloons or resorbable tissue tamponades [

15], discuss the risks of sclerotherapy, and outline the potential of oral therapy with tranexamic acid [

10]. Veteran patients then add pragmatic tips—such as how to humidify airways, log epistaxis episodes, or handle fatigue at work. Molecular biologists complement both perspectives through patient-centred mapping signalling cascades that contribute to disease onset.

Inviting representatives from pharmaceutical companies to patient meetings offers the potential to recruit candidates for clinical trials and involves the patients directly in the development process. Integrating bioinformatics expertise—such as through Germany’s Medical Informatics Initiative (MII)—provides additional value. The MII unifies clinical data from all university hospitals in Germany, standardises symptom and diagnosis codes and aims to eliminate redundancies to expose disease patterns earlier. Patients shall gain faster diagnosis, timely treatment, and better quality of life, while the resulting datasets are made accessible for medical research [

16].

The learning, however, is bidirectional: only patients can specify when epistaxis peaks (e.g., during nocturnal dryness or seasonal shifts) or how physical exertion might alter shear stress and force telangiectasia rupture. Such lived data feed back into, e.g., basic research in in vitro model development, computational simulation, and scalable platforms for drug screening purposes. This allows, e.g., the design and conceptualisation of experiments under more realistic conditions with the aim of recapitulating multiple environmental inputs essential for a better understanding of the complex pathomechanism of HHT.

4. Opportunities: Cross-Disease Synergies on Vascular Malformation Research

To investigate the molecular pathomechanisms of HHT in vitro and to facilitate novel drug screening approaches, adequate cell models must be established. As access to patient-derived primary vascular cells in rare diseases is limited and no central biobank for vascular anomalies yet exists, the technology of human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) is receiving rising interest in HHT research. By comparing healthy and genetically modified hiPSC-derived vascular cells, it might be possible to uncover how BMP signalling imbalances contribute to HHT. During the Scientific Symposium, a previously established heterozygous HHT-2 hiPSC-line was presented [

17]. These cells are currently used by two of the participating groups and provide a valuable contribution to HHT research.

Focusing on HHT genetics, the “second-hit hypothesis” was discussed, which suggests that a genetic mutation alone is not sufficient to trigger disease’s outbreak. Instead, an additional factor, such as a second somatic mutation in a previously healthy allele, might be necessary to initiate the development of VMs. This was already indicated by others [

18] and in this context, the relevance of in vitro models with a second genetic modification was emphasised. The outcome of this debate was that HHT-specific cellular models containing such modifications should be established. It was also considered whether an additional “hit” might be conducted by altered blood flow or dysfunctional cellular biomechanics. Based on this hypothesis, hiPSC-models focusing on applying biomechanical stress to the differentiated endothelial cells are currently being developed by one of the participating research groups. Combined with microfluidics and other mechanical devices, those cells can be exposed in the laboratory to conditions that aim to closely mimic the human vasculature and physical influences on patients’ vessels.

Furthermore, an improved protocol for the scalable differentiation of hiPSCs into endothelial cells and for the generation of blood vessel organoids was presented by one research group [

19]. This indicates ongoing efforts to establish sophisticated 3D cell culture models for rare vascular diseases. The group focuses on cerebral cavernous malformation (CCM), which leads to vascular abnormalities in the brain and is characterised by thin-walled blood vessels. With respect to these traits, CCM mirrors some aspects of HHT’s vascular phenotype. The learning from this was that integrating CCM-specific model systems and molecular targets into current HHT research strategies could unlock cross-disease synergies and raise the question of whether the pathomechanisms of other rare vascular disorders are more related to HHT than previously recognised.

Additionally, several BMP-related disorders, such as pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) and the rare musculoskeletal disorder fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP), might also share signalling aberrations with HHT, although the causal mutations differ [

20]. Nevertheless, there are some rare cases of the combined BMP-receptor type 2 and ALK1 mutation resulting in PAH and HHT within the same patient [

21]. The imbalance between BMP and TGF-β signalling in PAH and FOP causes alterations in cellular biomechanics, changes in extracellular matrix composition, and the promotion of pathways leading to cellular plasticity; in both diseases, endothelial cells seem to undergo endothelial–mesenchymal transition (EndMT) [

20,

22,

23]. During the meeting, it was discussed if there might be a similar pathomechanism in HHT. This would involve an overshooting of other TGF-β-related signalling pathways at the cost of BMP-9 signalling in endothelial cells, potentially also promoting EndMT and/or plasticity in HHT. Interestingly, also in CCM, the process of EndMT seems to play a crucial role during the development of vascular malformations [

24]. Using adequate model systems will reveal whether similarities and common mechanisms between HHT, CCM, PAH, and FOP exist.

Beyond cells, interesting in vivo models increasingly enter HHT research. The zebrafish (Danio rerio) is an excellent in vivo model for studying vascular development and malformations. Its embryos are transparent, thus allowing researchers to directly manipulate and image vascular development in real time as the embryo grows. Using different gene-editing methods to replicate VM-associated mutations in zebrafish embryos allows for the analysis of the resulting vascular phenotypes. Here, the CCM field once again is a good example of how a seemingly distinct research area could enrich the HHT society through partnership since zebrafish are more commonly employed in CCM research. Therefore, the participants explored potential collaborations to develop novel zebrafish lines for HHT studies. These models would allow the observation of AVM formation in real time within a more complex and perfused 3D environment using live cell imaging.

By using genetically modified mouse models, it was previously discovered that AVMs in HHT originate in venous endothelial cells, rather than in the arterial system [

25,

26]. This finding marks a significant step forward in understanding HHT pathogenesis. During the session, participants underscored that endothelial cells in both HHT and CCM animal models exhibit similar abnormalities in the expression of Krüppel-like factor 2/4 (

KLF 2/4). These transcription factors are key regulators of endothelial identity and vascular homeostasis, mediating responses to mechanical stimuli such as shear stress.

KLF alterations were detected and relevant particularly in low-flow regions in CCM and high-flow areas of AVMs in HHT [

27,

28]. This suggests a potential link between KLF-related pathways in both diseases, despite the differing shear stress conditions present in the affected vascular abnormalities. Collaborative research on these pathways was discussed, as well as on tailored HHT animal models, with the aim of unravelling the detailed molecular mechanisms of HHT.

Having a look beyond model systems, the role of the immune system in HHT might be of special interest [

29]. HHT itself is systemic and can manifest with a wide variety of symptoms and severity levels across patients. However, a reliable blood-based biomarker for HHT—ideally one that also tracks disease severity—has not been identified to date. In this context, a novel approach focusing on neutrophil granulocytes and their interaction with Pentraxin-3 (PTX3) was presented at the meeting. PTX3 is a soluble pattern recognition receptor secreted by various cell types, which plays an important role in immune defence by marking pathogens for elimination [

30]. Interestingly, one participating group observed that PTX3 plasma levels appear to inversely correlate with haemoglobin levels in patients with HHT. Since severe cases often show lower haemoglobin levels due to frequent bleeding, this suggests that PTX3 might reflect disease severity. Nevertheless, further studies are needed to validate PTX3 as a robust and specific biomarker for HHT.

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Patient gatherings unite affected individuals, clinicians, and researchers, aligning laboratory questions of improved biological model systems for drug testing with clinical needs. At the same time, patients and their families gain first-hand insight into molecular targets and realistic therapeutic timelines. This illustrates how face-to-face, community-driven encounters can strengthen motivation, mutual understanding, and, ultimately, translational progress.

For rare diseases like HHT, the lack of accessible and well-characterised biomaterials represents a major barrier to scientific progress. In this context, we support the creation of dedicated biobanks for diseases that lead to vascular disorders, in cooperation with medical focus centres, voluntary donors, and patient organisations. We also advocate for the development of a European-wide network to facilitate the collection and sharing of HHT samples. This initiative could significantly accelerate research efforts and support the discovery of new therapeutic strategies.

The meeting of the German HHT self-help group, together with participating researchers and clinicians, was a strong motivation to foster exchange between research fields that typically remain more separated but investigate shared and common pathomechanisms, model systems, and technical approaches. Now increasingly acknowledged, such patient-driven, transdisciplinary gatherings represent a valuable resource and can complement established scientific meetings. By promoting new dialogue, these events have the potential to accelerate progress in the HHT field.

The urge to create easily accessible biobanks and data repositories for vascular disorders, particularly rare disease patient material and data has become clear, along with the importance of better sharing and use of established and new model systems. In our opinion, instead of focusing on isolated research approaches, insights from disorders that are molecularly or phenotypically similar to HHT should be more intensely integrated, exploring the concept of cross-disease patterns of molecular dysregulation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.H. and I.K.; writing—original draft preparation, I.K.; writing—review and editing, I.K., F.D., S.K., C.H., and U.G.; and visualisation, C.H. and I.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We thank funding provided by the Open Access Publishing Fund of the Westfälische Hochschule, University of Applied Sciences, Gelsenkirchen, Bocholt, Recklinghausen, in Germany.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank the Morbus Osler Foundation and the Morbus Osler Self-Help Group e.V. for their warm welcome and for providing the opportunity to present our work directly to patients. We are also thankful for the inspiring talks of the other presenters during the self-help meeting (Thomas Kühnel, Tobias Geisel, Susanne Sernetz, Konstantin Jaschen, Guido Manfredi, Jürgen Stein, Ali Murad, Josef Schepers, Miriam Hübner) and the scientific symposium (Robert Mandic, Roxana Ola, Matthias Rath and Salim Abdelilah Seyfried) for their inspiring talks and interactions. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT V. 4.0 for the purposes of improving the English version of the text. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

S.K. is first president of the German HHT self-help group (Morbus Osler Selbsthilfe e.V.), U.G. is 3rd president of the German HHT self-help group (Morbus Osler-Selbsthilfe e.V.), president of the board of trustees of the German HHT foundation (Osler Stiftung). He is member of the Global Research and Medical Advisory Board of CureHHT, member of ISSVA, DiGGefA and Bundesverband Angiodysplasie e.V.. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest. No financial support or promotional interests influenced the authors’ opinion.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| ALK1 | Activin Receptor-like Kinase 1 |

| AVMs | Arteriovenous malformations |

| BMP | Bone morphogenetic protein |

| CCM | Cerebral cavernous malformation |

| ENG | Endoglin |

| EndMT | Endothelial-mesenchymal transition |

| FOP | Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| HHT | Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia |

| hiPSCs | Human induced pluripotent stem cells |

| KLF2/4 | Krüppel-like factor 2/4 |

| MII | Medical Informatics Initiative |

| PAH | Pulmonary arterial hypertension |

| PTX3 | Pentraxin-3 |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor β |

| VMs | Vascular malformations |

References

- Rendu, H.J. Épistaxis répétées chez un sujet porteur de petits angiomes cutanés et muqueux. Bull. Soc. Méd. Hôp. Paris 1896, 13, 731–733. [Google Scholar]

- Osler, W. On a family form of recurring epistaxis, associated with multiple telangiectases of the skin and mucous membranes. Bull. Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1901, 12, 333–337. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, F.P. Multiple hereditary developmental angiomata (telangiectases) of the skin and mucous membranes associated with recurring haemorrhages. Lancet 1907, 2, 160–162. [Google Scholar]

- Hammill, A.M.; Wusik, K.; Kasthuri, R.S. Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (HHT): A Practical Guide to Management. Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program 2021, 2021, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAllister, K.A.; Grogg, K.M.; Johnson, D.W.; Gallione, C.J.; Baldwin, M.A.; Jackson, C.E.; Helmbold, E.A.; Markel, D.S.; McKinnon, W.C.; Murrell, J. Endoglin, a TGF-Beta Binding Protein of Endothelial Cells, Is the Gene for Hereditary Haemorrhagic Telangiectasia Type 1. Nat. Genet. 1994, 8, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.W.; Berg, J.N.; Baldwin, M.A.; Gallione, C.J.; Marondel, I.; Yoon, S.J.; Stenzel, T.T.; Speer, M.; Pericak-Vance, M.A.; Diamond, A.; et al. Mutations in the Activin Receptor-like Kinase 1 Gene in Hereditary Haemorrhagic Telangiectasia Type 2. Nat. Genet. 1996, 13, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallione, C.J.; Repetto, G.M.; Legius, E.; Rustgi, A.K.; Schelley, S.L.; Tejpar, S.; Mitchell, G.; Drouin, E.; Westermann, C.J.J.; Marchuk, D.A. A Combined Syndrome of Juvenile Polyposis and Hereditary Haemorrhagic Telangiectasia Associated with Mutations in MADH4 (SMAD4). Lancet 2004, 363, 852–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shovlin, C.L.; Guttmacher, A.E.; Buscarini, E.; Faughnan, M.E.; Hyland, R.H.; Westermann, C.J.J.; Kjeldsen, A.D.; Plauchu, H. Diagnostic Criteria for Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (Rendu-Osler-Weber Syndrome). Am. J. Med. Genet. 2000, 91, 66–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinjikji, W.; Iyer, V.N.; Sorenson, T.; Lanzino, G. Cerebrovascular Manifestations of Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia. Stroke 2015, 46, 3329–3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faughnan, M.E.; Mager, J.J.; Hetts, S.W.; Palda, V.A.; Lang-Robertson, K.; Buscarini, E.; Deslandres, E.; Kasthuri, R.S.; Lausman, A.; Poetker, D.; et al. Second International Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 173, 989–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, S.; McWilliams, J.P. Approach to Pulmonary Arteriovenous Malformations: A Comprehensive Update. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhan, A.; Latif, M.A.; Minhas, A.; Weiss, C.R. Cardiac and Hemodynamic Manifestations of Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia. Int. J. Angiol. 2022, 31, 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Ielasi, L.; Tonnini, M.; Piscaglia, F.; Serio, I. Current Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management of Hepatic Involvement in Hereditary Hemorrhagic Teleangiectasia. World J. Hepatol. 2023, 15, 675–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Tsao, G. Liver Involvement in Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (HHT). J. Hepatol. 2007, 46, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Droege, F.; Lueb, C.; Thangavelu, K.; Stuck, B.A.; Lang, S.; Geisthoff, U. Nasal Self-Packing for Epistaxis in Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia Increases Quality of Life. Rhinology 2019, 57, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schepers, J.; Fleck, J.; Schaaf, J. Die Medizininformatik-Initiative und Seltene Erkrankungen: Routinedaten der nächsten Generation für Diagnose, Therapiewahl und Forschung [The medical informatics initiative and rare diseases: Next-generation routine data for diagnosis, therapy selection and research]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2022, 65, 1151–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang-Tischhauser, L.; Bette, M.; Rusche, J.R.; Roth, K.; Kasahara, N.; Stuck, B.A.; Bakowsky, U.; Wartenberg, M.; Sauer, H.; Geisthoff, U.W.; et al. Generation of a Syngeneic Heterozygous ACVRL1(Wt/Mut) Knockout iPS Cell Line for the In Vitro Study of HHT2-Associated Angiogenesis. Cells 2023, 12, 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snellings, D.A.; Gallione, C.J.; Clark, D.S.; Vozoris, N.T.; Faughnan, M.E.; Marchuk, D.A. Somatic Mutations in Vascular Malformations of Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia Result in Bi-Allelic Loss of ENG or ACVRL1. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2019, 105, 894–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowronek, D.; Pilz, R.A.; Saenko, V.V.; Mellinger, L.; Singer, D.; Ribback, S.; Weise, A.; Claaßen, K.; Büttner, C.; Brockmann, E.M.; et al. High-throughput differentiation of human blood vessel organoids reveals overlapping and distinct functions of the cerebral cavernous malformation proteins. Angiogenesis 2025, 28, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Duffhues, G.; Hiepen, C. Human iPSCs as Model Systems for BMP-Related Rare Diseases. Cells 2023, 12, 2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigelsky, C.M.; Jennings, C.; Lehtonen, R.; Minai, O.A.; Eng, C.; Aldred, M.A. BMPR2 Mutation in a Patient with Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension and Suspected Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2008, 146A, 2551–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelova, A.; Berman, M.; Al Ghouleh, I. Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2021, 34, 891–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medici, D.; Olsen, B.R. The Role of Endothelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Heterotopic Ossification. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2012, 27, 1619–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddaluno, L.; Rudini, N.; Cuttano, R.; Bravi, L.; Giampietro, C.; Corada, M.; Ferrarini, L.; Orsenigo, F.; Papa, E.; Boulday, G.; et al. EndMT Contributes to the Onset and Progression of Cerebral Cavernous Malformations. Nature 2013, 498, 492–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Gahn, J.; Banerjee, K.; Dobreva, G.; Singhal, M.; Dubrac, A.; Ola, R. Role of Endothelial PDGFB in Arterio-Venous Malformations Pathogenesis. Angiogenesis 2024, 27, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Furtado, J.; Poulet, M.; Chung, M.; Yun, S.; Lee, S.; Sessa, W.C.; Franco, C.A.; Schwartz, M.A.; Eichmann, A. Defective Flow-Migration Coupling Causes Arteriovenous Malformations in Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia. Circulation 2021, 144, 805–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rödel, C.J.; Otten, C.; Donat, S.; Lourenço, M.; Fischer, D.; Kuropka, B.; Paolini, A.; Freund, C.; Abdelilah-Seyfried, S. Blood Flow Suppresses Vascular Anomalies in a Zebrafish Model of Cerebral Cavernous Malformations. Circ. Res. 2019, 125, e43–e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, K.; Lin, Y.; Gahn, J.; Cordero, J.; Gupta, P.; Mohamed, I.; Graupera, M.; Dobreva, G.; Schwartz, M.A.; Ola, R. SMAD4 maintains the fluid shear stress set point to protect against arterial-venous malformations. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 133, e168352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droege, F.; Pylaeva, E.; Siakaeva, E.; Bordbari, S.; Spyra, I.; Thangavelu, K.; Lueb, C.; Domnich, M.; Lang, S.; Geisthoff, U.; et al. Impaired Release of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps and Anemia-Associated T Cell Deficiency in Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, R.; Wang, Z.; Wu, W.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, L.; Hu, J.; Luo, P.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Z.; et al. Molecular Insight into Pentraxin-3: Update Advances in Innate Immunity, Inflammation, Tissue Remodeling, Diseases, and Drug Role. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 156, 113783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).