Therapeutic Potential of Leptin in Neurodegenerative Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Regulation of Hippocampal Excitatory Synaptic Function by Leptin

3. Leptin Regulates the Trafficking of Glutamate Receptors

4. Leptin and Neurodegenerative Disease

5. Leptin Has Protective Actions in the CNS

6. Leptin Has Protective Effects at Synapses in Early AD

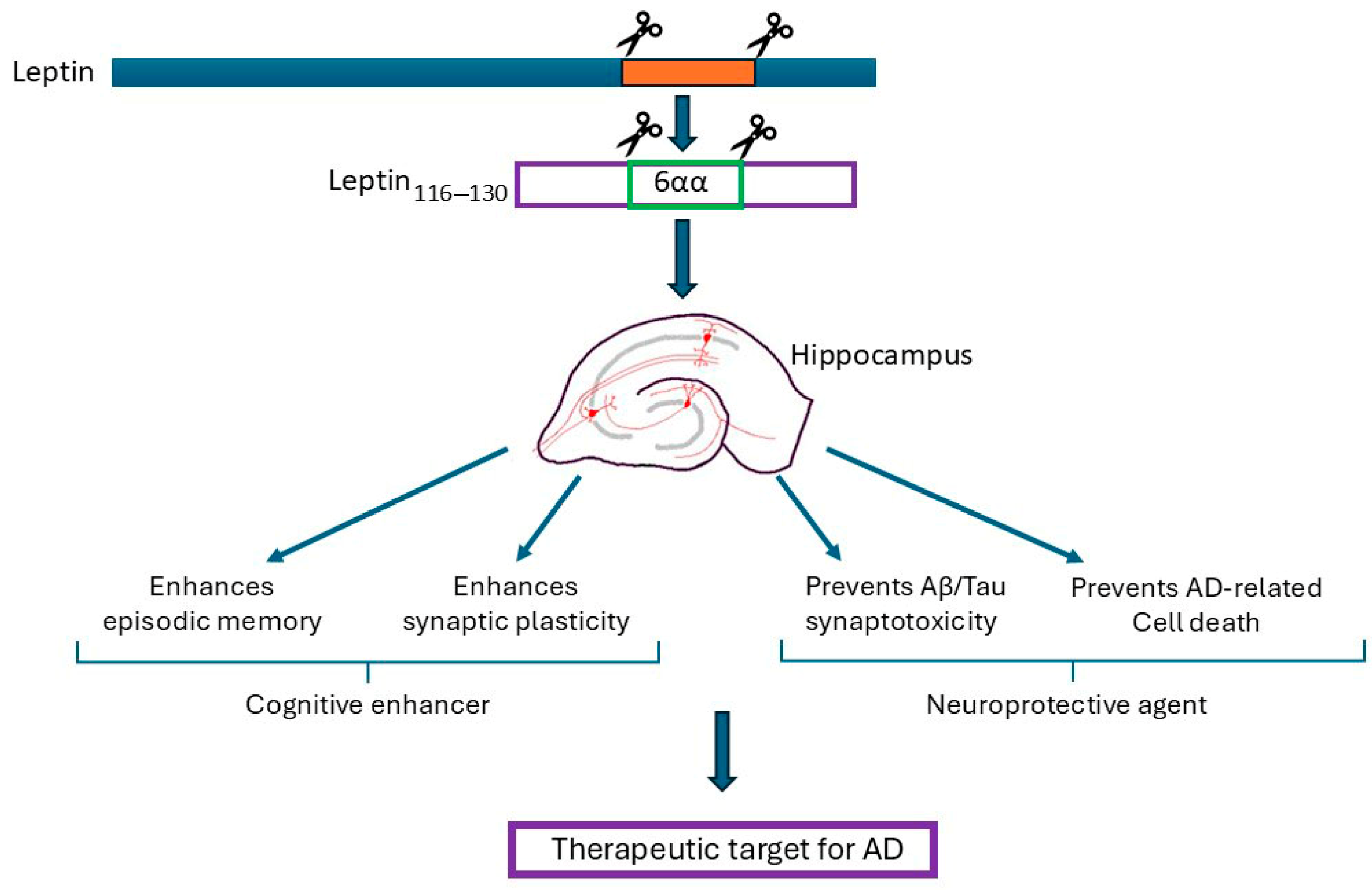

7. Leptin Has Pro-Cognitive Effects in AD Models

8. Therapeutic Potential of Leptin and Leptin-Derived Peptides

9. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maffei, M.; Halaas, J.; Ravussin, E.; Pratley, R.E.; Lee, G.H.; Zhang, Y.; Fei, H.; Kim, S.; Lallone, R.; Ranganathan, S.; et al. Leptin levels in human and rodent: Measurement of plasma leptin and ob RNA in obese and weight-reduced subjects. Nat. Med. 1995, 1, 1155–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihle, J.N. Cytokine receptor signalling. Nature 1995, 377, 591–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irving, A.; Harvey, J. Regulation of hippocampal synaptic function by the metabolic hormone leptin: Implications for health and disease. Prog. Lipid Res. 2021, 82, 101098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmquist, J.K.; Bjørbaek, C.; Ahima, R.S.; Flier, J.S.; Saper, C.B. Distributions of leptin receptor mRNA isoforms in the rat brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 1998, 395, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, M.W.; Seeley, R.J.; Campfield, L.A.; Burn, P.; Baskin, D.G. Identification of targets of leptin action in rat hypothalamus. J. Clin. Investig. 1996, 98, 1101–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercer, J.G.; Hoggard, N.; Williams, L.M.; Lawrence, C.B.; Hannah, L.T.; Trayhurn, P. Localization of leptin receptor mRNA and the long form splice variant (Ob-Rb) in mouse hypothalamus and adjacent brain regions by in situ hybridization. FEBS Lett. 1996, 387, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bliss, T.V.; Collingridge, G.L. A synaptic model of memory: Long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature 1993, 361, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanley, L.J.; Irving, A.J.; Rae, M.G.; Ashford, M.L.; Harvey, J. Leptin inhibits rat hippocampal neurons via activation of large conductance calcium-activated K+ channels. Nat. Neurosci. 2002, 5, 299–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irving, A.J.; Wallace, L.; Durakoglugil, D.; Harvey, J. Leptin enhances NR2B-mediated N-methyl-D-aspartate responses via a mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent process in cerebellar granule cells. Neuroscience 2006, 138, 1137–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Malley, D.; MacDonald, N.; Mizielinska, S.; Connolly, C.N.; Irving, A.J.; Harvey, J. Leptin promotes rapid dynamic changes in hippocampal dendritic morphology. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2007, 35, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerges, N.Z.; Aleisa, A.M.; Alkadhi, K.A. Impaired long-term potentiation in obese zucker rats: Possible involvement of presynaptic mechanism. Neuroscience 2003, 120, 535–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamal, A.; Ramakers, G.M.; Gispen, W.H.; Biessels, G.J. Hyperinsulinemia in rats causes impairment of spatial memory and learning with defects in hippocampal synaptic plasticity by involvement of postsynaptic mechanisms. Exp. Brain Res. 2013, 226, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuel Sánchez, D.M.; Limón, D.; Silva Gómez, A.B. Obese male Zucker rats exhibit dendritic remodeling in neurons of the hippocampal trisynaptic circuit as well as spatial memory deficits. Hippocampus 2022, 32, 828–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winocur, G.; Greenwood, C.E.; Piroli, G.G.; Grillo, C.A.; Reznikov, L.R.; Reagan, L.P.; McEwen, B.S. Memory impairment in obese Zucker rats: An investigation of cognitive function in an animal model of insulin resistance and obesity. Behav. Neurosci. 2005, 119, 1389–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farr, S.A.; Banks, W.A.; Morley, J.E. Effects of leptin on memory processing. Peptides 2006, 27, 1420–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayner, M.J.; Armstrong, D.L.; Phelix, C.F.; Oomura, Y. Orexin-A (Hypocretin-1) and leptin enhance LTP in the dentate gyrus of rats in vivo. Peptides 2004, 25, 991–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oomura, Y.; Hori, N.; Shiraishi, T.; Fukunaga, K.; Takeda, H.; Tsuji, M.; Matsumiya, T.; Ishibashi, M.; Aou, S.; Li, X.; et al. Leptin facilitates learning and memory performance and enhances hippocampal CA1 long-term potentiation and CaMK II phosphorylation in rats. Peptides 2006, 27, 2738–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brun, V.H.; Leutgeb, S.; Wu, H.Q.; Schwarcz, R.; Witter, M.P.; Moser, E.I.; Moser, M.B. Impaired spatial representation in CA1 after lesion of direct input from entorhinal cortex. Neuron 2008, 57, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, J.; Kyle, C.; Ekstrom, A.D. Complementary roles of human hippocampal subfields in differentiation and integration of spatial context. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2015, 27, 546–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; McGregor, G.; Irving, A.J.; Harvey, J. Leptin Induces a Novel Form of NMDA Receptor-Dependent LTP at Hippocampal Temporoammonic-CA1 Synapses. eNeuro 2015, 2, ENEURO.0007-15.2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, G.; Clements, L.; Farah, A.; Irving, A.J.; Harvey, J. Age-dependent regulation of excitatory synaptic transmission at hippocampal temporoammonic-CA1 synapses by leptin. Neurobiol. Aging 2018, 69, 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moult, P.R.; Cross, A.; Santos, S.D.; Carvalho, A.L.; Lindsay, Y.; Connolly, C.N.; Irving, A.J.; Leslie, N.R.; Harvey, J. Leptin regulates AMPA receptor trafficking via PTEN inhibition. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 4088–4101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanley, L.J.; Irving, A.J.; Harvey, J. Leptin enhances NMDA receptor function and modulates hippocampal synaptic plasticity. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, RC186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durakoglugil, M.; Irving, A.J.; Harvey, J. Leptin induces a novel form of NMDA receptor-dependent long-term depression. J. Neurochem. 2005, 95, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moult, P.R.; Milojkovic, B.; Harvey, J. Leptin reverses long-term potentiation at hippocampal CA1 synapses. J. Neurochem. 2009, 108, 685–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moult, P.R.; Harvey, J. NMDA receptor subunit composition determines the polarity of leptin induced synaptic plasticity. Neuropharmacology 2011, 61, 924–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auberson, Y.P.; Allgeier, H.; Bischoff, S.; Lingenhoehl, K.; Moretti, R.; Schmutz, M. 5-Phosphonomethylquinoxalinediones as competitive NMDA receptor antagonists with a preference for the human 1A/2A, rather than 1A/2B receptor composition. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2002, 12, 1099–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGregor, G.; Harvey, J. Leptin Regulation of Synaptic Function at Hippocampal TA-CA1 and SC-CA1 Synapses: Implications for Health and Disease. Neurochem. Res. 2019, 44, 650–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallarackal, A.J.; Kvarta, M.D.; Cammarata, E.; Jaberi, L.; Cai, X.; Bailey, A.M.; Thompson, S.M. Chronic stress induces a selective decrease in AMPA receptor-mediated synaptic excitation at hippocampal temporoammonic-CA1 synapses. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 15669–15674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kvarta, M.D.; Bradbrook, K.E.; Dantrassy, H.M.; Bailey, A.M.; Thompson, S.M. Corticosterone mediates the synaptic and behavioral effects of chronic stress at rat hippocampal temporoammonic synapses. J. Neurophysiol. 2015, 114, 1713–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, J.; Shanley, L.J.; O’Malley, D.; Irving, A.J. Leptin: A potential cognitive enhancer? Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2005, 33, 1029–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, T.; Zhu, M.; Dillon, C.; Sahin, G.S.; Rodriguez-Llamas, J.L.; Appleyard, S.M.; Wayman, G.A. Leptin Controls Glutamatergic Synaptogenesis and NMDA-Receptor Trafficking via Fyn Kinase Regulation of NR2B. Endocrinology 2020, 161, bqz030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collingridge, G.L.; Isaac, J.T.; Wang, Y.T. Receptor trafficking and synaptic plasticity. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004, 5, 952–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plant, K.; Pelkey, K.A.; Bortolotto, Z.A.; Morita, D.; Terashima, A.; McBain, C.J.; Collingridge, G.L.; Isaac, J.T. Transient Incorporation of Native GluR2-Lacking AMPA Receptors during Hippocampal Long-Term Potentiation. Nat. Neurosci. 2006, 9, 602–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Businaro, R.; Ippoliti, F.; Ricci, S.; Canitano, N.; Fuso, A. Alzheimer’s disease promotion by obesity: Induced mechanisms molecular links and perspectives. Curr. Gerontol. Geriatr. Res. 2012, 2012, 986823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, S.; Khemka, V.K.; Banerjee, A.; Chatterjee, G.; Ganguly, A.; Biswas, A. Metabolic risk factors of sporadic Alzheimer’s disease: Implications in the pathology, pathogenesis and treatment. Aging Dis. 2015, 6, 282–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores-Cordero, J.A.; Pérez-Pérez, A.; Jiménez-Cortegana, C.; Alba, G.; Flores-Barragán, A.; Sánchez-Margalet, V. Obesity as a Risk Factor for Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease: The Role of Leptin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wondmkun, Y.T. Obesity, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes: Associations and therapeutic implications. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2020, 13, 3611–3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheja, L.; Heeren, J. The endocrine function of adipose tissues in health and cardiometabolic disease. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 507–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, D.A.; Noel, J.; Collins, R.; O’Neill, D. Circulating leptin levels and weight loss in Alzheimer’s disease patients. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2001, 12, 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, H.; Pieper, C.; Schmader, K. The association of weight change in Alzheimer’s disease with severity of disease and mortality: A longitudinal analysis. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1998, 46, 1223–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieb, W.; Beiser, A.S.; Vasan, R.S.; Tan, Z.S.; Au, R.; Harris, T.B.; Roubenoff, R.; Auerbach, S.; DeCarli, C.; Wolf, P.A.; et al. Association of plasma leptin levels with incident Alzheimer disease and MRI measures of brain aging. JAMA 2009, 302, 2565–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilamand, M.; Bouaziz-Amar, E.; Dumurgier, J.; Cognat, E.; Hourregue, C.; Mouton-Liger, F.; Sanchez, M.; Troussière, A.C.; Martinet, M.; Hugon, J.; et al. Plasma Leptin Is Associated with Amyloid CSF Biomarkers and Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnosis in Cognitively Impaired Patients. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2023, 78, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charisis, S.; Short, M.I.; Bernal, R.; Kautz, T.F.; Treviño, H.A.; Mathews, J.; Dediós, A.G.V.; Muhammad, J.A.S.; Luckey, A.M.; Aslam, A.; et al. Leptin bioavailability and markers of brain atrophy and vascular injury in the middle age. Alzheimers Dement. 2024, 20, 5849–5860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oania, R.; McEvoy, L.K. Plasma leptin levels are not predictive of dementia in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Age Ageing 2015, 44, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teunissen, C.E.; van der Flier, W.M.; Scheltens, P.; Duits, A.; Wijnstok, N.; Nijpels, G.; Dekker, J.M.; Blankenstein, R.M.; Heijboer, A.C. Serum leptin is not altered nor related to cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2015, 44, 809–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greco, S.J.; Bryan, K.J.; Sarkar, S.; Zhu, X.; Smith, M.A.; Ashford, J.W.; Johnston, J.M.; Tezapsidis, N.; Casadesus, G. Leptin reduces pathology and improves memory in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2010, 19, 1155–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratap, A.A.; Holsinger, R.M.D. Altered Brain Leptin and Leptin Receptor Expression in the 5XFAD Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahima, R.S.; Bjorbaek, C.; Osei, S.; Flier, J.S. Regulation of neuronal and glial proteins by leptin: Implications for brain development. Endocrinology 1999, 140, 2755–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, C.; Mudd, J.; Hawkins, M. Neuroprotective effects of leptin in the context of obesity and metabolic disorders. Neurobiol. Dis. 2014, 72 Pt A, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, G.H.; Oldreive, C.; Harvey, J. Neuroprotective actions of leptin on central and peripheral neurons in vitro. Neuroscience 2008, 154, 1297–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Jiang, H.; Xu, X.; Duan, W.; Mattson, M.P. Leptin-mediated cell survival signaling in hippocampal neurons mediated by JAK STAT3 and mitochondrial stabilization. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 1754–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Buchan, M.; Vitanova, K.; Aitken, L.; Gunn-Moore, F.J.; Ramsay, R.R.; Doherty, G. Neuroprotective actions of leptin facilitated through balancing mitochondrial morphology and improving mitochondrial function. J. Neurochem. 2020, 155, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunnane, S.C.; Trushina, E.; Morland, C.; Prigione, A.; Casadesus, G.; Andrews, Z.B.; Beal, M.F.; Bergersen, L.H.; Brinton, R.D.; de la Monte, S.; et al. Brain energy rescue: An emerging therapeutic concept for neurodegenerative disorders of ageing. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020, 19, 609–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Chen, J. Leptin protects hippocampal CA1 neurons against ischemic injury. J. Neurochem. 2008, 107, 578–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.F.; Jin, Y.C.; Li, X.M.; Yang, Z.; Wang, D.; Cui, J.J. Protective effects of leptin against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury. Exp. Ther. Med. 2019, 17, 3282–3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doherty, G.H.; Beccano-Kelly, D.; Yan, S.D.; Gunn-Moore, F.J.; Harvey, J. Leptin prevents hippocampal synaptic disruption and neuronal cell death induced by amyloid beta. Neurobiol. Aging 2013, 34, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, K.; Morrow, K.; Markantoni, E.; Harvey, J. Leptin prevents aberrant targeting of tau to hippocampal synapses via PI 3 kinase driven inhibition of GSK3beta. J. Neurochem. 2023, 167, 520–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, S.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, T.; Wu, Z.; Huang, J.; Zhao, W. Hypo-methylated leptin receptor reduces cerebral ischaemia-reperfusion injury by activating the JAK2/STAT3 signalling pathway. J. Int. Med. Res. 2024, 52, 3000605241261912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cheng, D.; Jie, C.; Liu, T.; Huang, S.; Hu, S. leptin alleviates endoplasmic reticulum stress induced by cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury via the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Biosci. Rep. 2022, 42, BSR20221443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Park, C.S.; Lee, S.K.; Shin, D.W.; Kang, J.H. Leptin inhibits 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium-induced cell death in SH-SY5Y cells. Neurosci. Lett. 2006, 407, 240–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amantea, D.; Tassorelli, C.; Russo, R.; Petrelli, F.; Morrone, L.A.; Bagetta, G.; Corasaniti, M.T. Neuroprotection by leptin in a rat model of permanent cerebral ischemia: Effects on STAT3 phosphorylation in discrete cells of the brain. Cell Death Dis. 2011, 2, e238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Jin, Y.; Wang, D.; Cui, J. Neuroprotective effects of leptin on cerebral ischemia through JAK2/STAT3/PGC-1-mediated mitochondrial function modulation. Brain Res. Bull. 2020, 156, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Hou, Y.H.; Liao, Z.Y.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, X.X.; Wang, J.L.; Zhu, Y.B.; Shan, H.L.; Wang, P.Y.; Li, C.B.; et al. Neuroprotective Effects of Leptin on the APP/PS1 Alzheimer’s Disease Mouse Model: Role of Microglial and Neuroinflammation. Degener. Neurol. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2023, 13, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marwarha, G.; Dasari, B.; Prasanthi, J.R.; Schommer, J.; Ghribi, O. Leptin reduces the accumulation of Aβ and phosphorylated tau induced by 27-hydroxycholesterol in rabbit organotypic slices. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2010, 19, 1007–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedowicz, D.M.; Studzinski, C.M.; Weidner, A.M.; Platt, T.L.; Kingry, K.N.; Beckett, T.L.; Bruce-Keller, A.J.; Keller, J.N.; Murphy, M.P. Leptin regulates amyloid β production via the γ-secretase complex. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1832, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-González, R.; Alvira-Botero, M.X.; Robayo, O.; Antequera, D.; Garzón, M.; Martín-Moreno, A.M.; Brera, B.; de Ceballos, M.L.; Carro, E. Leptin gene therapy attenuates neuronal damages evoked by amyloid-β and rescues memory deficits in APP/PS1 mice. Gene Ther. 2014, 21, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, S.J.; Sarkar, S.; Johnston, J.M.; Tezapsidis, N. Leptin regulates tau phosphorylation and amyloid through AMPK in neuronal cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 380, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Guo, M.; Zhang, J.; Du, C.; Xing, Y. Leptin Regulates Tau Phosphorylation through Wnt Signaling Pathway in PC12 Cells. Neurosignals. 2016, 24, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cente, M.; Zorad, S.; Smolek, T.; Fialova, L.; Paulenka Ivanovova, N.; Krskova, K.; Balazova, L.; Skrabana, R.; Filipcik, P. Plasma Leptin Reflects Progression of Neurofibrillary Pathology in Animal Model of Tauopathy. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2022, 42, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Hong, S.; Shepardson, N.E.; Walsh, D.M.; Shankar, G.M.; Selkoe, D. Soluble oligomers of amyloid Beta protein facilitate hippocampal long-term depression by disrupting neuronal glutamate uptake. Neuron 2009, 62, 788–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, G.M.; Li, S.; Mehta, T.H.; Garcia-Munoz, A.; Shepardson, N.E.; Smith, I.; Brett, F.M.; Farrell, M.A.; Rowan, M.J.; Lemere, C.A.; et al. Amyloid-beta protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer’s brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat. Med. 2008, 14, 837–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drechsel, D.N.; Hyman, A.A.; Cobb, M.H.; Kirschner, M.W. Modulation of the dynamic instability of tubulin assembly by the microtubule-associated protein tau. Mol. Biol. Cell 1992, 3, 1141–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.C.; Teravskis, P.J.; Dummer, B.W.; Zhao, X.; Huganir, R.L.; Liao, D. Tau phosphorylation and tau mislocalization mediate soluble Abeta oligomer-induced AMPA glutamate receptor signaling deficits. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2014, 39, 1214–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, B.R.; Reed, M.N.; Su, J.; Penrod, R.D.; Kotilinek, L.A.; Grant, M.K.; Pitstick, R.; Carlson, G.A.; Lanier, L.M.; Yuan, L.L.; et al. Tau mislocalization to dendritic spines mediates synaptic dysfunction independently of neurodegeneration. Neuron 2010, 68, 1067–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, P.T.; Alafuzoff, I.; Bigio, E.H.; Bouras, C.; Braak, H.; Cairns, N.J.; Castellani, R.J.; Crain, B.J.; Davies, P.; Del Tredici, K.; et al. Correlation of Alzheimer disease neuropathologic changes with cognitive status: A review of the literature. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2012, 71, 362–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossenkoppele, R.; Schonhaut, D.R.; Scholl, M.; Lockhart, S.N.; Ayakta, N.; Baker, S.L.; O’neil, J.P.; Janabi, M.; Lazaris, A.; Cantwell, A.; et al. Tau PET patterns mirror clinical and neuroanatomical variability in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 2016, 139, 1551–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, M.; Shepardson, N.; Yang, T.; Chen, G.; Walsh, D.; Selkoe, D.J. Soluble amyloid beta-protein dimers isolated from Alzheimer cortex directly induce Tau hyperphosphorylation and neuritic degeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 5819–5824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, J.Q.; Zhang, J.; Hao, M.; Yang, J.; Han, Y.F.; Liu, X.J.; Shi, H.; Wu, M.N.; Liu, Q.S.; Qi, J.S. Leptin attenuates the detrimental effects of beta-amyloid on spatial memory and hippocampal later-phase long term potentiation in rats. Horm. Behav. 2015, 73, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, S.; Sato, N.; Uchio-Yamada, K.; Sawada, K.; Kunieda, T.; Takeuchi, D.; Kurinami, H.; Shinohara, M.; Rakugi, H.; Morishita, R. Diabetes-accelerated memory dysfunction via cerebrovascular inflammation and Abeta deposition in an Alzheimer mouse model with diabetes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 7036–7041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matochik, J.A.; London, E.D.; Yildiz, B.O.; Ozata, M.; Caglayan, S.; DePaoli, A.M.; Wong, M.L.; Licinio, J. Effect of leptin replacement on brain structure in genetically leptin-deficient adults. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 90, 2851–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Filho, G.J.; Babikian, T.; Asarnow, R.; Delibasi, T.; Esposito, K.; Erol, H.K.; Wong, M.L.; Licinio, J. Leptin replacement improves cognitive development. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, K.; Adamski, K.; Gomes, A.; Tuttle, E.; Kalden, H.; Cochran, E.; Brown, R.J. Effects of Metreleptin on Patient Outcomes and Quality of Life in Generalized and Partial Lipodystrophy. J. Endocr. Soc. 2021, 5, bvab019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlögl, H.; Villringer, A.; Miehle, K.; Fasshauer, M.; Stumvoll, M.; Mueller, K. Metreleptin Robustly Increases Resting-state Brain Connectivity in Treatment-naive Female Patients with Lipodystrophy. J. Endocr. Soc. 2023, 7, bvad072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebebrand, J.; Hildebrandt, T.; Schlögl, H.; Seitz, J.; Denecke, S.; Vieira, D.; Gradl-Dietsch, G.; Peters, T.; Antel, J.; Lau, D.; et al. The role of hypoleptinemia in the psychological and behavioral adaptation to starvation: Implications for anorexia nervosa. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2022, 141, 104807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milos, G.; Antel, J.; Kaufmann, L.K.; Barth, N.; Koller, A.; Tan, S.; Wiesing, U.; Hinney, A.; Libuda, L.; Wabitsch, M.; et al. Short-term metreleptin treatment of patients with anorexia nervosa: Rapid on-set of beneficial cognitive, emotional, and behavioral effects. Transl. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, P.; Leinung, M.C.; Ingher, S.P.; Lee, D.W. In vivo effects of leptin-related synthetic peptides on body weight and food intake in female ob/ob mice: Localization of leptin activity to domains between amino acid residues 106–140. Endocrinology 1997, 138, 1413–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekizadeh, Y.; Holiday, A.; Redfearn, D.; Ainge, J.A.; Doherty, G.; Harvey, J. A Leptin Fragment Mirrors the Cognitive Enhancing and Neuroprotective Actions of Leptin. Cereb. Cortex 2017, 27, 4769–4782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, G.; Holiday, A.; Malekizadeh, Y.; Manolescu, C.; Duncan, S.; Flewitt, I.; Hamilton, K.; MacLeod, B.; Ainge, J.A.; Harvey, J. Leptin-based hexamers facilitate memory and prevent amyloid-driven AMPA receptor internalisation and neuronal degeneration. J. Neurochem. 2023, 165, 809–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschstein, Z.; Vanga, G.R.; Wang, G.; Novakovic, Z.M.; Grasso, P. MA-[D-Leu-4]-OB3, a small molecule synthetic peptide leptin mimetic, improves episodic memory, and reduces serum levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and neurodegeneration in mouse models of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2020, 1864, 129697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Harvey, J. Therapeutic Potential of Leptin in Neurodegenerative Disease. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2969. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122969

Harvey J. Therapeutic Potential of Leptin in Neurodegenerative Disease. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):2969. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122969

Chicago/Turabian StyleHarvey, Jenni. 2025. "Therapeutic Potential of Leptin in Neurodegenerative Disease" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 2969. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122969

APA StyleHarvey, J. (2025). Therapeutic Potential of Leptin in Neurodegenerative Disease. Biomedicines, 13(12), 2969. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122969