Human Cytomegalovirus and Epstein–Barr Virus Infection in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Crossing the Diagnostic Barrier for Appropriate Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. hCMV and EBV Infection

3. hCMV and EBV Infection in IBD

4. Diagnosis of EBV and hCMV Infection

4.1. Cell Culture and Antigenemia

4.2. Traditional Histology, Immunohistochemistry, and in Situ Hybridization

4.3. Molecular Assays

4.4. Genotyping

4.5. Immunological Assays

5. Treatment of hCMV and EBV Infection

5.1. Therapeutic Options for HCMV Infection

5.2. Therapeutic Options for EBV Infection

5.3. Therapeutic Options for EBV and hCMV Simultaneous Infection

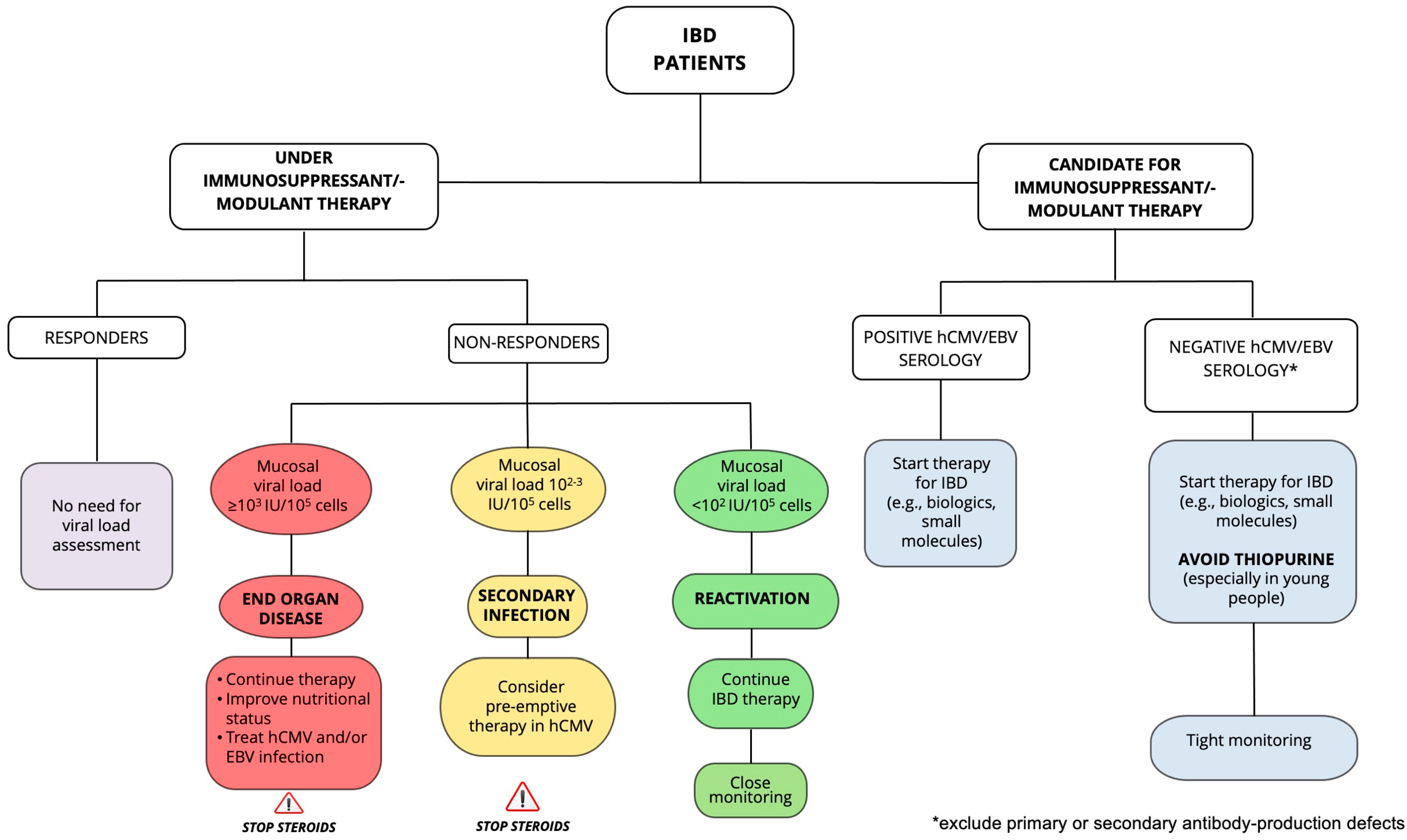

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CD | Crohn’s disease |

| EBV | Epstein–Barr virus |

| ELISA | enzymelinked immunosorbent assay |

| hCMV | human cytomegalovirus |

| IBD | inflammatory bowel disease |

| IG | immunoglobulin |

| IHC | immunohistochemistry |

| ISH | in situ hybridization |

| PTLD | post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease |

| qPCR | quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| UC | ulcerative colitis |

References

- Iacucci, M.; Santacroce, G.; Majumder, S.; Morael, J.; Zammarchi, I.; Maeda, Y.; Ryan, D.; Di Sabatino, A.; Rescigno, M.; Aburto, M.R.; et al. Opening the doors of precision medicine: Novel tools to assess intestinal barrier in inflammatory bowel disease and colitis-associated neoplasia. Gut 2024, 73, 1749–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, H.S.P.; Fiocchi, C. Immunopathogenesis of IBD: Current state of the art. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 13, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raine, T.; Danese, S. Breaking Through the Therapeutic Ceiling: What Will It Take? Gastroenterology 2022, 162, 1507–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuhair, M.; Smit, G.S.; Wallis, G.; Jabbar, F.; Smith, C.; Devleesschauwer, B. Estimation of the worldwide seroprevalence of cytomegalovirus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev. Med. Virol. 2019, 29, e2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Epstein-Barr Virus; IARC Monographs 2012; IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans: Lyon, France, 2012; pp. 49–92. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, H.S.; Jung, J.; Park, S.H.; Kim, H.J.; Hwang, S.W.; Yang, D.H.; Byeon, J.S.; Myung, S.J.; Yang, S.K.; Ye, B.D. Seroprevalence of viral infectious diseases and associated factors in Korean patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2022, 37, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linton, M.S.; Kroeker, K.; Fedorak, D.; Dieleman, L.; Fedorak, R.N. Prevalence of Epstein-Barr Virus in a population of patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A prospective cohort study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 38, 1248–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, J.A. Overview: Cytomegalovirus and the herpesviruses in transplantation. Am. J. Transplant. 2013, 13, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljungman, P.; Griffiths, P.; Paya, C. Definitions of cytomegalovirus infection and disease in transplant recipients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002, 34, 1094–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetgebuer, R.L.; van der Woude, C.J.; Bakker, L.; van der Eijk, A.A.; de Ridder, L.; de Vries, A.C. The diagnosis and management of CMV colitis in IBD patients shows high practice variation: A national survey among gastroenterologists. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 57, 1321–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.; Fluxá, D.; Farraye, F.A.; Kröner, P.T. Cytomegalovirus-related colitis in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2022, 37, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, A.N.; Rojas Feria, M.; de la Cruz Ramírez, M.D.; Gómez Izquierdo, L.; Trigo Salado, C.; Herrera Justiniano, J.M.; Leo Carnerero, E. Impact of Epstein-Barr virus infection on inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) clinical outcomes. Rev. Esp. Enfermedades Dig. 2022, 114, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharzik, T.; Ellul, P.; Greuter, T.; Rahier, J.F.; Verstockt, B.; Abreu, C.; Albuquerque, A.; Allocca, M.; Esteve, M.; Farraye, F.A.; et al. ECCO Guidelines on the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Management of Infections in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2021, 15, 879–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrum, F.; Caviness, K.; Zagallo, P. Human cytomegalovirus persistence. Cell Microbiol. 2012, 14, 644–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effrey, J.; Ohen, I.C. Epstein–Barr Virus Infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 343, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravender, T. Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and infectious mononucleosis. Adolesc. Med. State Art Rev. 2010, 251, 21–23. [Google Scholar]

- Roizman, B.; Sears, A.E. An inquiry into the mechanisms of herpes simplex virus latency. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1987, 41, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorley-Lawson, D.A. EBV Persistence-Introducing the Virus. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2015, 390, 151–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, C.; Abendroth, A.; Slobedman, B. A novel viral transcript with homology to human interleukin-10 is expressed during latent human cytomegalovirus infection. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 1440–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarska, K.; Chowdhury, R.; Tobin, J.W.D.; Swain, F.; Keane, C.; Boyle, S.; Khanna, R.; Gandhi, M.K. Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphomas decoded. Br. J. Haematol. 2024, 204, 415–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, R.M.; Zhu, J.; Budgeon, L.; Christensen, N.D.; Meyers, C.; Sample, C.E. Efficient replication of Epstein-Barr virus in stratified epithelium in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 16544–16549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewendorf, A.; Benedict, C.A. Modulation of host innate and adaptive immune defenses by cytomegalovirus: Timing is everything. J. Intern. Med. 2010, 267, 483–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotton, C.N.; Torre-Cisneros, J.; International CMV Symposium Faculty; Aguado, J.M.; Alain, S.; Baldanti, F.; Baumann, G.; Boeken, U.; de la Calle, M.; Carbone, J.; et al. Cytomegalovirus in the transplant setting: Where are we now and what happens next? A report from the International CMV Symposium 2021. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2022, 24, e13977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayharsh, G.A.; Loftus, E.V., Jr.; Sandborn, W.J.; Tremaine, W.J.; Zinsmeister, A.R.; Witzig, T.E.; Macon, W.R.; Burgart, L.J. Epstein-Barr virus-positive lymphoma in patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine. Gastroenterology 2002, 122, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, O.M.; Krams, S.M. The Immune Response to Epstein Barr Virus and Implications for Posttransplant Lymphoproliferative Disorder. Transplantation 2017, 101, 2009–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankaran-Walters, S.; Ransibrahmanakul, K.; Grishina, I.; Hung, J.; Martinez, E.; Prindiville, T. Dandekar SEpstein-Barr virus replication linked to Bcell proliferation in inflamed areas of colonic mucosa of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J. Clin. Virol. 2011, 50, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwamoto, G.K.; Monick, M.M.; Clark, B.D.; Auron, P.E.; Stinski, M.F.; Hunninghake, G.W. Modulation of interleukin 1 beta gene expression by the immediate early genes of human cytomegalovirus. J. Clin. Investig. 1990, 85, 1853–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanai, H.; Shimizu, N.; Nagasaki, S.; Mitani, N.; Okita, K. Epstein-Barr virus infection of the colon with inflammatory bowel disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1999, 94, 1582–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertalot, G.; Villanacci, V.; Gramegna, M.; Orvieto, E.; Negrini, R.; Saleri, A.; Terraroli, C.; Ravelli, P.; Cestari, R.; Viale, G. Evidence of Epstein-Barr virus infection in ulcerative colitis. Dig. Liver Dis. 2001, 33, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Simpson, N.; Klipfel, N.; Debose, R.; Barr, N.; Laine, L. Cytomegalovirus infection in patients with active inflammatory bowel disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2010, 55, 1059–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Chen, X.; Pan, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L. Epstein-Barr Virus and Human Cytomegalovirus Infection in Intestinal Mucosa of Chinese Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 915453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Jiang, X.; Chen, J.; Mao, Q.; Zhao, X.; Sun, X.; Zhong, L.; Rong, L. Chronic active Epstein-Barr virus infection involving gastrointestinal tract mimicking inflammatory bowel disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020, 20, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzarotto, T.; Monte, P.D.; Landini, M.P. Recent advances in the diagnosis of cytomegalovirus infection. Ann. Biol. Clin. 1996, 6, 54–65. [Google Scholar]

- Niller, H.H.; Bauer, G. Epstein-Barr Virus: Clinical Diagnostics. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1532, 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotton, C.N.; Kumar, D.; Caliendo, A.M.; Huprikar, S.; Chou, S.; Danziger-Isakov, L.; Humar, A.; The Transplantation Society International CMV Consensus Group. The Third International Consensus Guidelines on the Management of Cytomegalovirus in Solid-organ Transplantation. Transplantation 2018, 102, 900–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Kato, J.; Kuriyama, M.; Hiraoka, S.; Kuwaki, K.; Yamamoto, K. Specific endoscopic features of ulcerative colitis complicated by cytomegalovirus infection. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetgebuer, R.L.; van der Woude, C.J.; de Ridder, L.; Doukas, M.; de Vries, A.C. Clinical and endoscopic complications of Epstein-Barr virus in inflammatory bowel disease: An illustrative case series. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2019, 34, 923–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Störkmann, H.; Rödel, J.; Stallmach, A.; Reuken, P.A. Are CMV-predictive scores in inflammatory bowel disease useful in clinical practice? Z. Gastroenterol. 2020, 58, 868–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillet, S.; Pozzetto, B.; Jarlot, C.; Paul, S.; Roblin, X. Management of cytomegalovirus infection in inflammatory bowel diseases. Dig. Liver Dis. 2012, 44, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W.; Boo, S.J.; Ye, B.D.; Kim, C.L.; Yang, S.K.; Kim, J.; Kim, S.A.; Park, S.H.; Park, S.K.; Yang, D.H.; et al. Clinical utility of cytomegalovirus antigenemia assay and blood cytomegalovirus DNA PCR for cytomegaloviral colitis patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2014, 8, 693–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langner, C.; Magro, F.; Driessen, A.; Ensari, A.; Mantzaris, G.J.; Villanacci, V.; Becheanu, G.; Borralho Nunes, P.; Cathomas, G.; Fries, W.; et al. The histopathological approach to inflammatory bowel disease: A practice guide. Virchows Arch. 2014, 464, 511–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, A.M.; Guo, F.P.; Copland, A.P.; Pai, R.K.; Pinsky, B.A. A comparison of CMV detection in gastrointestinal mucosal biopsies using immunohistochemistry and PCR performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2013, 37, 995–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zidar, N.; Ferkolj, I.; Tepeš, K.; Štabuc, B.; Kojc, N.; Uršič, T.; Petrovec, M. Diagnosing cytomegalovirus in patients with inflammatory bowel disease--by immunohistochemistry or polymerase chain reaction? Virchows Arch. 2015, 466, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, P.; James, P.; Cordeiro, E.; Mallick, R.; Shukla, T.; McCurdy, J.D. Diagnostic Accuracy of Blood-Based Tests and Histopathology for Cytomegalovirus Reactivation in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.; McCurdy, J.D.; Loftus, E.V.; Bruining, D.H., Jr.; Enders, F.T.; Killian, J.M.; Smyrk, T.C. Effects of antiviral therapy for patients with inflammatory bowel disease and a positive intestinal biopsy forcytomegalovirus. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 13, 949–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clos-Parals, A.; Rodríguez-Martínez, P.; Cañete, F.; Mañosa, M.; Ruiz-Cerulla, A.; José Paúles, M.; Llaó, J.; Gordillo, J.; Fumagalli, C.; Garcia-Planella, E.; et al. Prognostic Value of the Burden of Cytomegalovirus Colonic Reactivation Evaluated by Immunohistochemical Staining in Patients with Active Ulcerative Colitis. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2019, 13, 385–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kredel, L.I.; Mundt, P.; van Riesen, L.; Jöhrens, K.; Hofmann, J.; Loddenkemper, C.; Siegmund, B.; Preiß, J.C. Accuracy of diagnostic tests and a new algorithm for diagnosing cytomegalovirus colitis in inflammatory bowel diseases: A diagnostic study. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2019, 34, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCurdy, J.D.; Jones, A.; Enders, F.T.; Killian, J.M.; Loftus, E.V., Jr.; Smyrk, T.C.; Bruining, D.H. A model for identifying cytomegalovirus in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 13, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Chen, H.; Zu, X.; Hao, X.; Feng, R.; Zhang, S.; Chen, B.; Zeng, Z.; Chen, M.; Ye, Z.; et al. Epstein-Barr virus infection in ulcerative colitis: A clinicopathologic study from a Chinese area. Therap. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2020, 13, 1756284820930124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spieker, T.; Herbst, H. Distribution and phenotype of Epstein-Barr virus-infected cells in inflammatory bowel disease. Am. J. Pathol. 2000, 157, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, P.A.; Coates, P.J.; Ansari, B.; Hopwood, D. Regulation of cell number in the mammalian gastrointestinal tract: The importance of apoptosis. J. Cell Sci. 1994, 107 Pt 12, 3569–3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccocioppo, R.; Racca, F.; Scudeller, L.; Piralla, A.; Formagnana, P.; Pozzi, L.; Betti, E.; Vanoli, A.; Riboni, R.; Kruzliak, P.; et al. Differential cellular localization of Epstein-Barr virus and human cytomegalovirus in the colonic mucosa of patients with active or quiescent inflammatory bowel disease. Immunol. Res. 2016, 64, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganzenmueller, T.; Henke-Gendo, C.; Schlué, J.; Wedemeyer, J.; Huebner, S.; Heim, A. Quantification of cytomegalovirus DNA levels in intestinal biopsies as a diagnostic tool for CMV intestinal disease. J. Clin. Virol. 2009, 46, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfon, P.; Berger, P.; Khiri, H.; Martineau, A.; Pénaranda, G.; Merlin, M.; Faucher, C. Algorithm based on CMV kinetics DNA viral load for preemptive therapy initiation after hematopoietic cell transplantation. J. Med. Virol. 2011, 83, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henmi, Y.; Berger, P.; Khiri, H.; Martineau, A.; Pénaranda, G.; Merlin, M.; Faucher, C. Cytomegalovirus infection in ulcerative colitis assessed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction: Risk factors effects of immunosuppressants. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2018, 63, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tun, G.S.Z.; Raza, M.; Hale, M.F.; Lobo, A.J. Polymerase chain reaction for detection of mucosal cytomegalovirus infection in patients with acute ulcerative colitis. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2019, 32, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, B.; Atay, A.; Kayhan, M.A.; Ozin, Y.O.; Gokce, D.T.; Altunsoy, A.; Guner, R. Tissue quantitative RT-PCR test for diagnostic significance of cytomegalovirus infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and treatment response: Cytomegalovirus infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Medicine 2023, 102, E34463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccocioppo, R.; Racca, F.; Paolucci, S.; Campanini, G.; Pozzi, L.; Betti, E.; Riboni, R.; Vanoli, A.; Baldanti, F.; Corazza, G.R. Human cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus infection in inflammatory bowel disease: Need for mucosal viral load measurement. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 1915–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryer, J.F.; Heath, A.B.; Minor, P.D.; Collaborative Study Group. A collaborative study to establish the 1st WHO International Standard for human cytomegalovirus for nucleic acid amplification technology. Biologicals 2016, 44, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattayalertyanyong, O.; Limsrivilai, J.; Phaophu, P.; Subdee, N.; Horthongkham, N.; Pongpaibul, A.; Angkathunyakul, N.; Chayakulkeeree, M.; Pausawasdi, N.; Charatcharoenwitthaya, P. Performance of Cytomegalovirus Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction Assays of Fecal and Plasma Specimens for Diagnosing Cytomegalovirus Colitis. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2023, 14, e00574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, T.; Tavakolian, S.; Goudarzi, H.; Pourmand, M.R.; Faghihloo, E. Global estimate of phenotypic and genotypic ganciclovir resistance in cytomegalovirus infections among HIV and organ transplant patients; A systematic review and meta-analysis. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 141, 104012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahar, S.; Hokama, A.; Iraha, A.; Ohira, T.; Kinjo, T.; Hirata, T.; Kinjo, T.; Parrott, G.L.; Fujita, J. Distribution of cytomegalovirus genotypes among ulcerative colitis patients in Okinawa, Japan. Intest. Res. 2018, 16, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reusing, J.O.; Agena, F.; Kotton, C.N.; Campana, G.; Pierrotti, L.C.; David-Neto, E. QuantiFERON-CMV as a Predictor of CMV Events During Preemptive Therapy in CMV-seropositive Kidney Transplant Recipients. Transplantation 2024, 108, 985–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccocioppo, R.; Mengoli, C.; Betti, E.; Comolli, G.; Cassaniti, I.; Piralla, A.; Kruzliak, P.; Caprnda, M.; Pozzi, L.; Corazza, G.R.; et al. Human Cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus specific immunity in patients with ulcerative colitis. Clin. Exp. Med. 2021, 21, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavaglio, F.; Cassaniti, I.; d’Angelo, P.; Zelini, P.; Comolli, G.; Gregorini, M.; Rampino, T.; Del Frate, L.; Meloni, F.; Pellegrini, C.; et al. Immune Control of Human Cytomegalovirus (HCMV) Infection in HCMV-Seropositive Solid Organ Transplant Recipients: The Predictive Role of Different Immunological Assays. Cells 2024, 13, 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walti, C.S.; Khanna, N.; Avery, R.K.; Helanterä, I. New Treatment Options for Refractory/Resistant CMV Infection. Transpl. Int. 2023, 36, 11785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Fournier, M.; Sundberg, A.K.; Song, I.H. Maribavir: Mechanism of action, clinical, and translational science. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2024, 17, e13696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano, C.; Giménez, E.; Albert, E.; Piñana, J.L.; Navarro, D. Immunovirology of cytomegalovirus infection in allogeneic stem cell transplant recipients undergoing prophylaxis with letermovir: A narrative review. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e29005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossi, P.A.; Peghin, M. Recent advances in cytomegalovirus infection management in solid organ transplant recipients. Curr. Opin. Organ. Transplant. 2024, 29, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotton, C.N.; Torre-Cisneros, J.; Yakoub-Agha, I.; CMV International Symposium Faculty. Slaying the ‘Troll of Transplantation’-new frontiers in cytomegalovirus management: A report from the CMV International Symposium 2023. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2024, 26, e14183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storek, J.; Lindsay, J. Rituximab for posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder—Therapeutic, preemptive, or prophylactic? Bone Marrow Transplant. 2024, 59, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pociupany, M.; Snoeck, R.; Dierickx, D.; Andrei, G. Treatment of Epstein-Barr Virus infection in immunocompromised patients. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2024, 225, 116270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Lyu, H.; Guo, R.; Cao, X.; Feng, J.; Jin, X.; Lu, W.; Zhao, M. Epstein–Barr virus–associated cellular immunotherapy. Cytotherapy 2023, 25, 903–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciccocioppo, R.; Comoli, P.; Gallia, A.; Basso, S.; Baldanti, F.; Corazza, G.R. Autologous human cytomegalovirus-specific cytotoxic T cells as rescue therapy for ulcerative enteritis in primary immunodeficiency. J. Clin. Immunol. 2014, 34, 681–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J.I. Therapeutic vaccines for herpesviruses. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 134, e179483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| DEFINITION | MEANING | CLINICAL FEATURES |

|---|---|---|

| Infection | Isolation of the virus or detection of viral proteins/nucleic acid in any biological sample. | |

| Primary infection | Appearance of de novo specific antibodies in a seronegative patient, provided that passive transfer via immunoglobulin or blood products can be excluded. Detection of viral components in an individual previously found to be seronegative. | Asymptomatic in most cases. Those few symptomatic cases presenting with a self-limited disease (“mononucleosis”) commonly characterized by fever, malaise, leukopenia, low platelet count, and elevated liver enzymes and C-reactive protein. |

| Secondary Infection | Switch from the latent to lytic phase. Presence of viral DNA in a biological sample in an individual known to be seropositive. | Asymptomatic in immunocompetent hosts. Symptomatic in immunocompromised hosts. |

| Re-infection | Detection of a viral strain that is different from the strain that was the cause of the patient’s original infection. | Usually symptomatic. |

| Reactivation | Switch from the latent to lytic phase. Reactivation is assumed if the two viral strains found in two episodes of secondary infection are found to be indistinguishable. | In immunocompetent subjects, reactivation may occur sporadically and is usually clinically silent. In immunocompromised people, reactivation of viral infection may lead to end-organ or systemic disease. |

| Lytic phase | Complete expression of viral proteins, including those needed for virion assembly and envelopment. | Symptomatic (similar to primary infection). |

| Latent phase | The condition in which the virus genome is retained within the human genome in specific cell populations and viral gene expression is deeply limited, in the absence of replication of the virus. | Asymptomatic. |

| Chronic active secondary infection | Chronically active lytic phase with persistent presence of viral DNA in biological samples. | Presence of prolonged fever, malaise, hepatosplenomegaly, and pancytopenia. |

| Systemic disease | Presence of high viral load in peripheral blood. | Presence of systemic involvement including fever, malaise, fatigue, and eventually splenomegaly, cytopenia, and lymphadenopathy. |

| End-organ disease | Presence of high viral load in biological samples from any body organ/tissue/fluid. | Presence of signs and symptoms related to the damage of the target organ. |

| TECHNIQUE | TYPE OF SPECIMEN | ADVANTAGES | DISADVANTAGES |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viral culture | Tissue or blood |

|

|

| Antigenemia (pp65) | Blood |

|

|

| Antibodies IgM and IgG | Serum |

|

|

| Histopathology | Tissue |

|

|

| Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) | Tissue or blood |

|

|

| Genotyping | Tissue or blood |

|

|

| ELISpot Assay (immune response) | Blood |

|

|

| Flow cytometry (immune response) | Blood |

|

|

| MHC-multimer-based assay (immune response) | Blood |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ciccocioppo, R.; Caldart, F.; Piralla, A.; Betti, E.; Frulloni, L.; Di Sabatino, A.; Baldanti, F. Human Cytomegalovirus and Epstein–Barr Virus Infection in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Crossing the Diagnostic Barrier for Appropriate Management. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2915. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122915

Ciccocioppo R, Caldart F, Piralla A, Betti E, Frulloni L, Di Sabatino A, Baldanti F. Human Cytomegalovirus and Epstein–Barr Virus Infection in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Crossing the Diagnostic Barrier for Appropriate Management. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):2915. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122915

Chicago/Turabian StyleCiccocioppo, Rachele, Federico Caldart, Antonio Piralla, Elena Betti, Luca Frulloni, Antonio Di Sabatino, and Fausto Baldanti. 2025. "Human Cytomegalovirus and Epstein–Barr Virus Infection in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Crossing the Diagnostic Barrier for Appropriate Management" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 2915. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122915

APA StyleCiccocioppo, R., Caldart, F., Piralla, A., Betti, E., Frulloni, L., Di Sabatino, A., & Baldanti, F. (2025). Human Cytomegalovirus and Epstein–Barr Virus Infection in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Crossing the Diagnostic Barrier for Appropriate Management. Biomedicines, 13(12), 2915. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122915