The Relationship Between Composite Inflammatory Indices and Dry Eye in Hashimoto’s Disease-Induced Hypothyroid Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Ophthalmic Assessments

2.3. Laboratory Measurements

2.4. Statistical Analysis

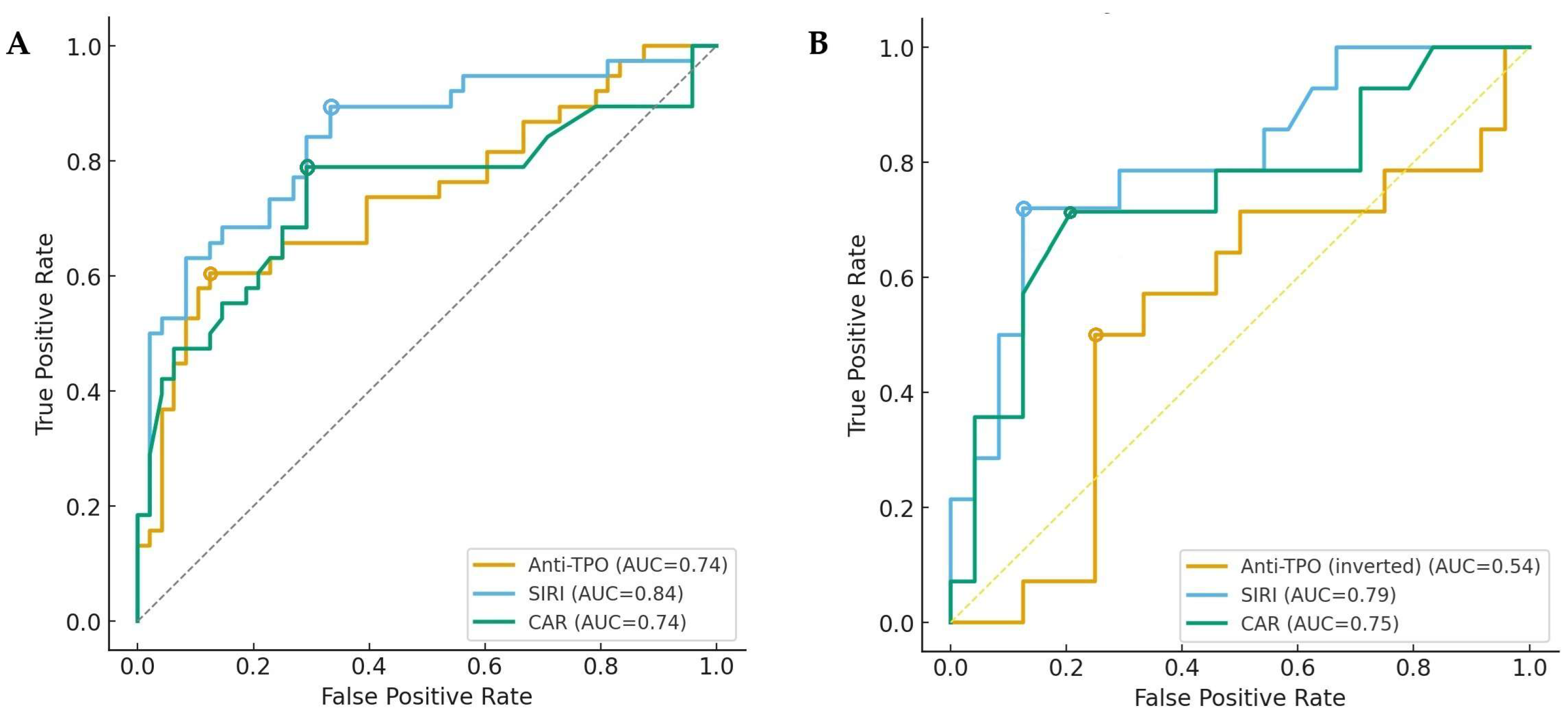

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ragusa, F.; Fallahi, P.; Elia, G.; Gonnella, D.; Paparo, S.R.; Giusti, C.; Churilov, L.P.; Ferrari, S.M.; Antonelli, A. Hashimotos’ thyroiditis: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinic and therapy. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 33, 101367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Chen, Y.; Shen, Y.; Tian, R.; Sheng, Y.; Que, H. Global prevalence and epidemiological trends of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1020709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.Y.; Ye, X.P.; Zhou, Z.; Zhu, C.F.; Li, R.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, R.J.; Li, L.; Liu, W.; Wang, Z.; et al. Lymphocyte infiltration and thyrocyte destruction are driven by stromal and immune cell components in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randelovic, K.; Jukic, T.; Tesija Kuna, A.; Susic, T.; Hanzek, M.; Stajduhar, A.; Vatavuk, Z.; Petric Vickovic, I. Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis and Dry Eye Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wan, X.; Ye, H.; Yang, P.; Zhou, S.; Chen, Z.; Xin, C.; Zhou, X.; Le, Q.; Hong, J. Clinical characteristics of dry eye patients with thyroid disorders: A cross-sectional study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2025, 25, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, J.P.; Nichols, K.K.; Akpek, E.K.; Caffery, B.; Dua, H.S.; Joo, C.K.; Liu, Z.; Nelson, J.D.; Nichols, J.J.; Tsubota, K.; et al. TFOS DEWS II Definition and Classification Report. Ocul. Surf. 2017, 15, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, A.; Lause, M.; Kumar, P. Ophthalmic manifestations of endocrine disorders-endocrinology and the eye. Transl. Pediatr. 2017, 6, 286–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.; Wang, C.; Zhou, H. Inflammation mechanism and anti-inflammatory therapy of dry eye. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1307682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrand, K.F.; Fridman, M.; Stillman, I.O.; Schaumberg, D.A. Prevalence of Diagnosed Dry Eye Disease in the United States Among Adults Aged 18 Years and Older. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 182, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss-Albee, D.M.; Horowitz, A.; Parham, P.; Blish, C.A. Coordinated regulation of NK receptor expression in the maturing human immune system. J. Immunol. 2014, 193, 4871–4879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chauhan, S.K.; Lee, H.S.; Saban, D.R.; Dana, R. Chronic dry eye disease is principally mediated by effector memory Th17 cells. Mucosal Immunol. 2014, 7, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messmer, E.M.; von Lindenfels, V.; Garbe, A.; Kampik, A. Matrix Metalloproteinase 9 Testing in Dry Eye Disease Using a Commercially Available Point-of-Care Immunoassay. Ophthalmology 2016, 123, 2300–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garriz, A.; Morokuma, J.; Bowman, M.; Pagni, S.; Zoukhri, D. Effects of proinflammatory cytokines on lacrimal gland myoepithelial cells contraction. Front. Ophthalmol. 2022, 2, 873486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Shi, J.; Xie, C.M.; Yao, X.L. Dry Eye Disease: Oxidative Stress on Ocular Surface and Cutting-Edge Antioxidants. Glob. Chall. 2025, 9, e00068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhujel, B.; Oh, S.H.; Kim, C.M.; Yoon, Y.J.; Chung, H.S.; Ye, E.A.; Lee, H.; Kim, J.Y. Current Advances in Regenerative Strategies for Dry Eye Diseases: A Comprehensive Review. Bioengineering 2023, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, T. Assessment of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Patients with Dry Eye Disease. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2018, 26, 1219–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.F.; Pu, Q.; Ma, Q.; Zhu, W.; Li, X.Y. Neutrophil/Lymphocyte Ratio as an Inflammatory Predictor of Dry Eye Disease: A Case-Control Study. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2021, 17, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirvani, M.; Soufi, F.; Nouralishahi, A.; Vakili, K.; Salimi, A.; Lucke-Wold, B.; Mousavi, F.; Mohammadzadehsaliani, S.; Khanzadeh, S. The Diagnostic Value of Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio as an Effective Biomarker for Eye Disorders: A Meta-Analysis. Biomed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 5744008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liang, P.; Tong, C.; Tao, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, J.; Fang, Z.; Zhao, Z. Systemic Immune-Inflammatory Index and Systemic Inflammatory Response Index in the Assessment of Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome Caused by Wasp Stings. J. Inflamm. Res. 2025, 18, 11177–11187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzeli, U.S.; Dogan, A.G.; Sahin, T. The Relationship Between Systemic Immune Inflammatory Level and Dry Eye in Patients with Sjogren’s Syndrome. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozarslan Ozcan, D.; Kurtul, B.E.; Ozcan, S.C.; Elbeyli, A. Increased Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index Levels in Patients with Dry Eye Disease. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2022, 30, 588–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhalwani, A.Y.; Baqar, R.; Algadaani, R.; Bamallem, H.; Alamoudi, R.; Jambi, S.; Abd El Razek Mady, W.; Sannan, N.S.; Anwar Khan, M. Investigating Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte and C-Reactive Protein-to-Albumin Ratios in Type 2 Diabetic Patients with Dry Eye Disease. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2024, 32, 925–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffman, R.M.; Christianson, M.D.; Jacobsen, G.; Hirsch, J.D.; Reis, B.L. Reliability and validity of the ocular surface disease index. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2000, 118, 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Marques, J.V.; Martinez-Albert, N.; Talens-Estarelles, C.; Garcia-Lazaro, S.; Cervino, A. Repeatability of Non-invasive Keratograph Break-Up Time measurements obtained using Oculus Keratograph 5M. Int. Ophthalmol. 2021, 41, 2473–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novack, G.D.; Asbell, P.; Barabino, S.; Bergamini, M.V.W.; Ciolino, J.B.; Foulks, G.N.; Goldstein, M.; Lemp, M.A.; Schrader, S.; Woods, C.; et al. TFOS DEWS II Clinical Trial Design Report. Ocul. Surf. 2017, 15, 629–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujak, R.; Daghir-Wojtkowiak, E.; Kaliszan, R.; Markuszewski, M.J. PLS-Based and Regularization-Based Methods for the Selection of Relevant Variables in Non-targeted Metabolomics Data. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2016, 3, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jett, S.; Malviya, N.; Schelbaum, E.; Jang, G.; Jahan, E.; Clancy, K.; Hristov, H.; Pahlajani, S.; Niotis, K.; Loeb-Zeitlin, S.; et al. Endogenous and Exogenous Estrogen Exposures: How Women’s Reproductive Health Can Drive Brain Aging and Inform Alzheimer’s Prevention. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 831807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, E.; Ibrahimi, E.; Ntalianis, E.; Cauwenberghs, N.; Kuznetsova, T. Integrating Metabolomics Domain Knowledge with Explainable Machine Learning in Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Classification. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabek, A.; Stanimirova, I.; Deja, S.; Barg, W.; Kowal, A.; Korzeniewska, A.; Orczyk-Pawilowicz, M.; Baranowski, D.; Gdaniec, Z.; Jankowska, R.; et al. Fusion of the 1H NMR data of serum, urine and exhaled breath condensate in order to discriminate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Metabolomics 2015, 11, 1563–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Pan, G.; Liu, Z.; Kong, Y.; Wang, D. Association of levels of metabolites with the safe margin of rectal cancer surgery: A metabolomics study. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanska, E.; Saccenti, E.; Smilde, A.K.; Westerhuis, J.A. Double-check: Validation of diagnostic statistics for PLS-DA models in metabolomics studies. Metabolomics 2012, 8, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Liu, W.; Mei, P.; Liu, Y.; Cai, J.; Liu, L.; Wang, J.; Ling, X.; Wang, M.; Cheng, Y.; et al. The large language model diagnoses tuberculous pleural effusion in pleural effusion patients through clinical feature landscapes. Respir. Res. 2025, 26, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLong, E.R.; DeLong, D.M.; Clarke-Pearson, D.L. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: A nonparametric approach. Biometrics 1988, 44, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, E.; Kilickan, E.; Ecemis, G.; Beyazyildiz, E.; Colak, R. Presence of Dry Eye in Patients with Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis. J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 2014, 754923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altin Ekin, M.; Karadeniz Ugurlu, S.; Egrilmez, E.D.; Oruk, G.G. Ocular Surface Changes in Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis Without Thyroid Ophthalmopathy. Eye Contact Lens 2021, 47, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, R.; Yao, K.; Hu, Y.; Chen, L. Discrepancy between subjectively reported symptoms and objectively measured clinical findings in dry eye: A population based analysis. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e005296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, B.D.; Crews, L.A.; Messmer, E.M.; Foulks, G.N.; Nichols, K.K.; Baenninger, P.; Geerling, G.; Figueiredo, F.; Lemp, M.A. Correlations between commonly used objective signs and symptoms for the diagnosis of dry eye disease: Clinical implications. Acta Ophthalmol. 2014, 92, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczesna-Iskander, D.H.; Muzyka-Wozniak, M.; Llorens Quintana, C. The efficacy of ocular surface assessment approaches in evaluating dry eye treatment with artificial tears. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz Tugan, B.; Ozkan, B. Evaluation of Meibomian Gland Loss and Ocular Surface Changes in Patients with Mild and Moderate-to-Severe Graves’ Ophthalmopathy. Semin. Ophthalmol. 2022, 37, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Chen, X.; Ma, Y.; Lin, X.; Yu, X.; He, S.; Luo, C.; Xu, W. Analysis of tear inflammatory molecules and clinical correlations in evaporative dry eye disease caused by meibomian gland dysfunction. Int. Ophthalmol. 2020, 40, 3049–3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, E.W.; Tai, Y.H.; Wu, H.L.; Dai, Y.X.; Chen, T.J.; Cherng, Y.G.; Lai, S.C. The Association between Autoimmune Thyroid Disease and Ocular Surface Damage: A Retrospective Population-Based Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Huang, Q.; Sun, S.; Zhou, K.; Wang, X.; Pan, K.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Han, Q.; Si, C.; et al. Thyroid antibodies in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis patients are positively associated with inflammation and multiple symptoms. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomar, A.P.d.; Montolío, A.; Cegoñino, J.; Dhanda, S.K.; Lio, C.T.; Bose, T. The innate immune cell profile of the cornea predicts the onset of ocular surface inflammatory disorders. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murad, R.; Alfeel, A.H.; Shemote, Z.; Kumar, P.; Babker, A.; Osman, A.L.; Altoum, A.A. The role of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in assessing hypothyroidism Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Ital. J. Med. 2025, 19, 1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onalan, E.; Donder, E. Neutrophil and platelet to lymphocyte ratio in patients with hypothyroid Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Acta Biomed. 2020, 91, 310–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aktas, G.; Sit, M.; Dikbas, O.; Erkol, H.; Altinordu, R.; Erkus, E.; Savli, H. Elevated neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in the diagnosis of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2017, 63, 1065–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erinc, O.; Yesilyurt, S.; Senat, A. A Comprehensive Evaluation of Hemogram-Derived Inflammatory Indices in Hashimoto Thyroiditis and Non-Immunogenic Hypothyroidism. Acta Endocrinol. 2023, 19, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Wang, B.; Han, W.; Yu, B.; Ci, J.; An, F. Correlation between systemic inflammatory response index and thyroid function: 2009-2012 NHANES results. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1305386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekeryapan, B.; Uzun, F.; Buyuktarakci, S.; Bulut, A.; Oner, V. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio Increases in Patients with Dry Eye. Cornea 2016, 35, 983–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, F.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, X.; Jiang, W.; Wang, L.; Zhuang, X.; Zheng, C.; Ni, Y.; Chen, L. NETosis may play a role in the pathogenesis of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2018, 11, 537–547. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tecchio, C.; Micheletti, A.; Cassatella, M.A. Neutrophil-derived cytokines: Facts beyond expression. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Zhao, F.; Cheng, H.; Su, M.; Wang, Y. Macrophage polarization: An important role in inflammatory diseases. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1352946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, K.C.; Jeong, I.Y.; Park, Y.G.; Yang, S.Y. Interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha levels in tears of patients with dry eye syndrome. Cornea 2007, 26, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, G.; Blanco, T.; Singh, R.B.; Kahale, F.; Wang, S.; Chen, Y.; Dana, R. IL-6 induces Treg dysfunction in desiccating stress-induced dry eye disease. Exp. Eye Res. 2024, 246, 110006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Mallem, K.; Asbell, P.A.; Ying, G.S. A latent profile analysis of tear cytokines and their association with severity of dry eye disease in the Dry Eye Assessment and Management (DREAM) study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M. From C-Reactive Protein to Interleukin-6 to Interleukin-1: Moving Upstream To Identify Novel Targets for Atheroprotection. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grebenciucova, E.; VanHaerents, S. Interleukin 6: At the interface of human health and disease. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1255533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Control Group (n = 43) | Hypothyroidism HT | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without DED (n = 48) | With DED (n = 38) | |||

| Age, years | 46.7 ± 12.6 | 45.4 ± 9.0 | 47.4 ± 15.1 | 0.734 |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 32 (74.4) | 37 (77.1) | 29 (76.3) | 0.999 |

| Male | 11 (25.6) | 11 (22.9) | 9 (23.7) | |

| Duration of illness, years | - | 2 (1–4) | 3 (1–4) | 0.846 |

| Schirmer test, mm | 8 (5–15) | 15 (8–30) | 7 (4–15) | <0.001 * |

| NIBUT, s | 7 (5–9) | 12 (5–20) | 5 (4–8) | 0.002 * |

| OSDI | 17 (15–20) | 8 (3–14) | 28 (20–38) | <0.001 * |

| Laboratory findings | ||||

| fT4, ng/dL | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | <0.001 * |

| TSH, mIU/L | 1.9 (1.5–3) | 8.9 (7.0–15.8) | 10.7 (7.9–17.6) | <0.001 * |

| Anti-TPO, IU/mL | 0.8 (0.1–2.40) | 426 (245–565) | 748 (403–1070) | <0.001 * |

| Leukocytes, ×103 µL | 7.0 ± 1.6 | 7.4 ± 1.3 | 7.5 ± 1.6 | 0.321 |

| Lymphocytes, ×103 µL | 2.6 ± 0.8 | 2.5 ± 0.5 | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 0.047 * |

| Neutrophils, ×103 µL | 3.8 ± 0.9 | 4.0 ± 0.6 | 4.4 ± 1.0 | 0.001 * |

| Monocytes, ×103 µL | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.028 * |

| Platelets, ×103 µL | 265.5 ± 54.9 | 262.3 ± 56.4 | 278.8 ± 50.1 | 0.858 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 4.3 ± 0.3 | 4.4 ± 0.4 | 4.4 ± 0.5 | 0.486 |

| CRP, mg/dL | 3.5 (2.5–5.5) | 3.5 (2.5–5.3) | 5.3 (4.6–6.7) | 0.001 * |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 0.461 |

| NLR | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 2.0 ± 0.4 | <0.001 * |

| PLR | 117.3 ± 40.7 | 108.2 ± 36.6 | 114.3 ± 29.7 | 0.475 |

| SII | 429.5 ± 140.4 | 444.6 ± 125.2 | 482.9 ± 143.2 | 0.198 |

| SIRI | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | <0.001 * |

| CAR | 0.8 (0.6–1.2) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 1.2 (1.0–1.7) | <0.001 * |

| PNI | 55.4 ± 4.6 | 56.5 ± 3.2 | 55.2 ± 4.5 | 0.257 |

| Variables | HT–HypoT | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without DED (n = 48) | Mild to Moderate DED (n = 24) | Severe DED (n = 14) | ||

| Age, years | 45.4 ± 9.0 | 45.3 ± 16.2 | 51.1 ± 12.8 | 0.258 |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 37 (77.1) | 18 (75.0) | 11 (78.6) | 0.999 |

| Male | 11 (22.9) | 6 (25.0) | 3 (21.4) | |

| Duration of illness, years | 2 (1–4) | 2.5 (1–4) | 3 (1–4) | 0.742 |

| Schirmer test, mm | 15 (8–30) | 9 (4–15) | 8 (4–14) | 0.005 * |

| NIBUT, s | 12 (5–20) | 6 (4–9) | 5 (3–8) | 0.003 * |

| OSDI | 8 (3–14) | 22 (17–28) | 43 (34–65) | <0.001 * |

| Laboratory findings | ||||

| fT4, ng/dL | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.901 |

| TSH, mIU/L | 8.9 (7.0–15.8) | 11.4 (7.9–17.6) | 12.1 (8.8–23.4) | 0.238 |

| Anti-TPO, IU/mL | 426 (245–565) | 731 (343–1066) | 774 (403–1097) | 0.001 * |

| Leukocytes, ×103 µL | 7.4 ± 1.3 | 7.5 ± 1.7 | 7.3 ± 1.3 | 0.899 |

| Lymphocytes, ×103 µL | 2.5 ± 0.8 | 2.3 ± 0.7 | 2.3 ± 0.5 | 0.207 |

| Neutrophils, ×103 µL | 4.0 ± 0.6 | 4.2 ± 1.0 | 4.6 ± 0.9 | <0.001 * |

| Monocytes, ×103 µL | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.001 * |

| Platelets, ×103 µL | 262.3 ± 56.4 | 270.0 ± 59.6 | 279.2 ± 42.7 | 0.192 |

| Albumine, g/dL | 4.4 ± 0.4 | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 4.5 ± 0.7 | 0.440 |

| Creatinin, mg/dL | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.364 |

| CRP, mg/dL | 3.5 (2.5–5.3) | 5.0 (3.2–5.4) | 6.7 (6.1–9.3) | <0.001 * |

| NLR | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 2.3 ± 0.5 | <0.001 * |

| PLR | 108.2 ± 36.6 | 112.7 ± 34.5 | 118.5 ± 19.2 | 0.659 |

| SII | 444.6 ± 125.2 | 471.1 ± 164.4 | 503.2 ± 98.2 | 0.331 |

| SIRI | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | <0.001 * |

| CAR | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 1.1 (0.7–1.4) | 1.5 (1.2–1.7) | <0.001 * |

| PNI | 56.5 ± 3.2 | 55.4 ± 5.1 | 54.8 ± 2.3 | 0.270 |

| Characteristics | Component Model | Index + Core Model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % variation explained by latent factors | ||||||

| For predictor variables (inflammatory mediators) | 0.92 | 0.95 | ||||

| For outcome variables (DED) | 0.70 | 0.75 | ||||

| Number of used latent factors | 1 | 1 | ||||

| AUC (95% CI) | 0.90 (0.85–0.95) | 0.95 (0.90–0.99) | ||||

| Number of correctly classified (95% CI) | 82.5% (77–88%) | 90.2% (85–96%) | ||||

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Factor | VIP | +/− | Factor | VIP | +/− | |

| Top inflammatory markers responsible for outcome | Anti-TPO | 1.48 | + | Anti-TPO | 1.25 | + |

| Neutrophils | 1.10 | + | SIRI | 2.49 | + | |

| Monocytes | 1.12 | + | CAR | 1.56 | + | |

| CRP | 0.85 | + | ||||

| Variables | Univariable Regression | Multivariable Regression | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| DED+ vs. DED− | ||||

| Anti-TPO | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | <0.001 * | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | <0.001 * |

| Lymphocytes | 0.57 (0.30–0.98) | 0.047 * | – | – |

| Neutrophils | 2.34 (1.24–4.40) | 0.009 * | – | – |

| Monocytes | 1.07 (1.01–1.13) | 0.015 * | – | – |

| CRP | 1.63 (1.25–2.12) | <0.001 * | – | – |

| NLR | 1.03 (1.01–1.06) | <0.001 * | – | – |

| SIRI | 1.07 (1.04–1.10) | <0.001 * | 1.06 (1.03–1.10) | <0.001 * |

| CAR | 1.26 (1.11–1.43) | <0.001 * | 1.22 (1.04–1.44) | <0.001 * |

| Nagelkerke R2 = 0.66 | ||||

| Severe DED vs. mild to moderate DED | ||||

| Anti-TPO | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | 0.632 | – | - |

| Neutrophils | 3.21 (1.12–9.20) | 0.030 * | – | - |

| Monocytes | 1.02 (1.01–1.05) | 0.022 * | – | - |

| CRP | 1.28 (1.02–1.71) | 0.025 * | – | - |

| NLR | 1.19 (1.01–1.40) | 0.038 * | – | - |

| SIRI | 1.05 (1.02–1.09) | <0.001 * | 1.05 (1.02–1.10) | <0.001 * |

| CAR | 1.16 (1.04–1.27) | <0.001 * | 1.19 (1.05–1.32) | <0.001 * |

| Nagelkerke R2 = 0.51 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kabakci, A.K.; Cakir, D.C.; Comez, A.T. The Relationship Between Composite Inflammatory Indices and Dry Eye in Hashimoto’s Disease-Induced Hypothyroid Patients. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2675. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112675

Kabakci AK, Cakir DC, Comez AT. The Relationship Between Composite Inflammatory Indices and Dry Eye in Hashimoto’s Disease-Induced Hypothyroid Patients. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(11):2675. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112675

Chicago/Turabian StyleKabakci, Asli Kirmaci, Derya Cepni Cakir, and Arzu Taskiran Comez. 2025. "The Relationship Between Composite Inflammatory Indices and Dry Eye in Hashimoto’s Disease-Induced Hypothyroid Patients" Biomedicines 13, no. 11: 2675. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112675

APA StyleKabakci, A. K., Cakir, D. C., & Comez, A. T. (2025). The Relationship Between Composite Inflammatory Indices and Dry Eye in Hashimoto’s Disease-Induced Hypothyroid Patients. Biomedicines, 13(11), 2675. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112675