1. Introduction

Nucleic-acid-based therapeutics have a high potential to treat many terminal diseases caused by genetic defects [

1]. Their power dwells in their adaptability towards the target. For instance, a rationally designed and developed oligonucleotide therapeutic sequences that work towards one target gene can be adapted to interfere with a new target gene by changing the nucleotides within the sequence. Compared with traditional small-molecule drugs, oligonucleotide therapeutics are different with respect to the size, the chemical structure and the mode of action. The chemical structure of the small-molecule drug determines the target specificity, the tissue distribution and the metabolism. In the case of oligonucleotide-based therapies, the sequence directs target recognition and the chemistry of the backbone and the vehicle determines tissue distribution and metabolism [

2].

There are currently two main types of oligonucleotide therapeutics, antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) and short interfering oligonucleotides (siRNA). While ASOs are single-stranded (4–10 kDa) and siRNA are double-stranded (approx. 14 kDa), these oligonucleotide therapeutics also have different intracellular modes of action. ASOs can exert their action in the cytoplasm and in the nuclei by taking advantage of RNase H enzyme to cut the hybridized target mRNA or by simple steric blocking [

3]. On the other hand, siRNA is only active in the cytoplasm and employs the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) to perform its action [

4].

In the past years, both types of nucleic-acid-based therapeutics have been approved by the federal agencies for drug approval [

5]. In particular, from 2013 until 2021, seven ASOs and four siRNA oligonucleotide therapeutics were approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) [

1]. These drugs are targeting rare, previously untreatable diseases, including Duchenne muscular dystrophy, transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis, spinal muscular atrophy and some common conditions, such as hypercholesterolemia [

1].

However, natural oligonucleotide sequences, having a negatively charged backbones and being susceptible to enzymatic and chemical degradation, lack drug-like properties. The stability of various modified oligonucleotide sequences in bio-fluids and human serum is studied and described [

6,

7,

8]. In order to overcome the challenges of possible off-target effects combined with improved chemical and enzymatic stability, previous work has reported many chemical modification strategies of the backbone and nucleotides. The approved ASOs usually contain a phosphorothioate (PS) backbone (e.g., the drug Mipomersen) where one non-binding oxygen is replaced by a sulfur, [

9], 2’-O-(2-methoxyethyl) (2’-MOE) nucleotide modification (e.g., the drugs: Inotersen, Nusinersen and Volanesorsen) [

10,

11], or phosphorodiamidate-morpholino (PMO) units (e.g., the drugs Eteplirsen, Golodirsen and Casimersen) that replace the natural sugar-phosphate backbone [

12,

13,

14]. On the other hand, the siRNA therapeutics on the market, including the drugs Givosiran, Lumasiran and Inclisiran, comprise partial PS backbone modification, 2’-O-methyl (2’OMe) and 2’fluoro (2’F) nucleotide modification. In addition, N-acetyl galactosamine dendrimer is covalently attached to the 3’terminus of their sense strand [

15,

16,

17]. Moreover, the structure of the approved drug Patisiran as siRNA includes 2’OMe nucleoside modification and two dT-oligodeoxyribonucleotides overhanging on the 3’ terminus of both the sense and antisense sequences. To achieve intracellular delivery, Patisiran is formulated as a lipid nanoparticle drug using ionizable lipids [

18].

Recently, Nishina et al. reported efficient gene silencing performed by a novel type of therapeutic oligonucleotides designed as antisense double-stranded, heteroduplex oligonucleotides (HDOs) [

19,

20]. The authors developed short HDO of DNA and RNA where the DNA antisense strand was designed as a DNA/LNA gapmer while the complementary RNA sense strand was 2’OMe-modified and conjugated with α-tocopherol. The authors reported that this type of HDO was more potent to knockdown the target mRNA compared with the parent single-stranded DNA/LNA ASO [

19]. Moreover, Asami et al. reported on an efficient gene suppression by a DNA/DNA double-stranded oligonucleotide in vivo [

21]. The authors showed that the ASO/DNA and ASO/RNA HDO have higher potency and efficacy in vivo than the parent single-stranded ASO. In addition, a report by Yoshioka et al. showed improved intracellular potency of an ASO/RNA HDO to silence microRNA in vivo. This candidate could silence the target microRNA with 12-fold higher efficiency than the parent single-stranded ASO [

22]. Furthermore, Rodrigues et al. developed a novel way of silencing oligonucleotides called polypurine reverse Hoogsteen hairpins (PPRHs) [

23]. The authors designed the PPRHs as DNA formed by two antiparallel polypurine oligonucleotides linked by a five-thymidine loop and reported a decrease in target mRNA levels in prostate cancer cells and decreased tumor volume [

24]. The same group using repair-PPRH also reported on a successful correction of different single-point mutations in mammalian cells [

25].

Despite significant progress in the field of oligonucleotide therapeutics, the biggest issue preventing its widespread use is the low efficiency of intracellular delivery to organs and tissues other than the liver [

26]. To date, efficient delivery of oligonucleotide therapeutics is reported through local delivery (intravitreal and intrathecal) [

26,

27] and to the liver [

28]. The delivery strategies include chemical modifications of the nucleotides and the backbone, covalent conjugation with molecules or biomolecules and lipid nanoparticle formulation. While considering the rationally modified sequence design to avoid off-target side effects (i.e., sequence degradation and sequence-related toxicities), there is immense need for new delivery technologies that will facilitate the clinical translation of the oligonucleotide therapeutics.

Herein, we explored the design and synthesis of novel multi-functionalized HDOs for targeted delivery and gene silencing in HeLa cells. We tested the intracellular delivery and the suppression of the target gene activity.

2. Materials and Methods

Modified and functionalized oligonucleotides were ordered from LubioScience GmbH, Switzerland. Folate-Peg3-Azide was ordered from Base click GmbH, Germany. The thiol/azide-modified peptides (P1 and P2) were ordered from Gen Script Biotech. Lipofectamine 3K, RNAiMax and Opti MEM were ordered from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Green-fluorescent-protein (GFP)-expressing HeLa cells were purchased from Amsbio. All other reagents were ordered from Sigma Aldrich, Buchs, Switzerland.

2.1. Design Tools and Strategy

We selected a series of single-stranded ASOs (ASO1-ASO6, six in total) that target the open reading frame (ORF) of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene (in HeLa cells expressing GFP) manually or used the Sfold software for statistical folding of nucleic acids. The GFP HDO consists of ASO5/ASO5.1/ASO5.2 and its complementary functionalized RNA sequence (ASOss).

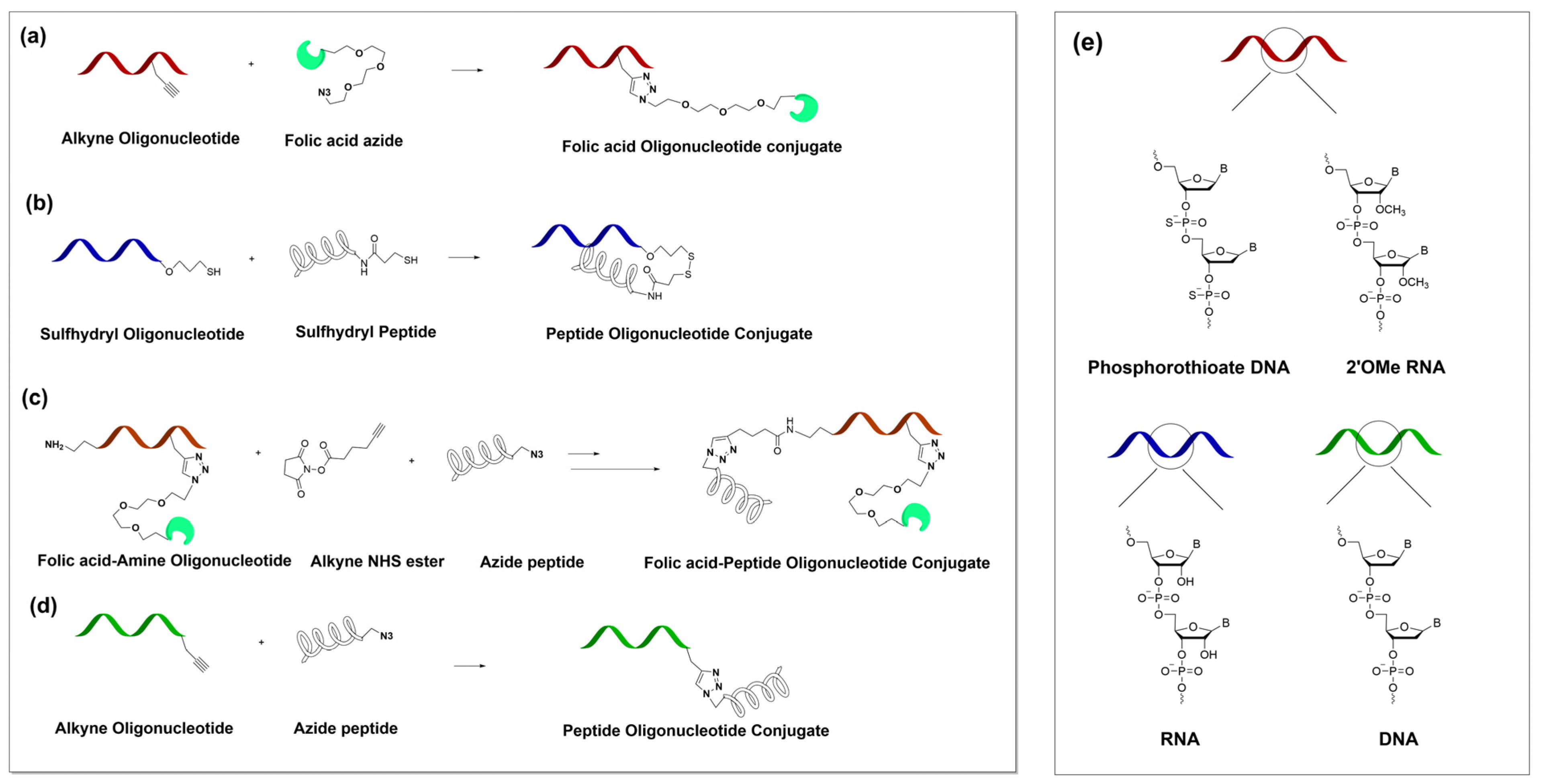

The advanced ASO5 analogue, ASO5.2 was rationally designed as a gapmer with a full phosphorothioate backbone and with three 2’OMe modifications on the two termini. Additionally, we installed an alkyne functionalization at internal position 16 (counting 5’→3’). The ASOss was designed as a pure RNA oligonucleotide functionalized with a thiol group at the 5’ terminus (

Scheme 1 and

Scheme S1). We also included a scrambled control for ASO5 named ASOscr.

We designed the Bcl2 HDO targeting the

Bcl2 gene using a similar concept. The antisense oligonucleotide, Bcl2 ASO.1 was designed as a full phosphorothioate backbone oligonucleotide with partial three 2’OMe modifications at both termini 5′ and 3′ and an alkyne functionalization at internal position 16 (counting 5′→3′). Additionally, this sequence contains an amino group modifier at the 5′ terminus (

Scheme S1). The sense strand, Bcl2ss was designed as a pure DNA sequence and contained alkyne functionalization at the 3’ terminus. Scrambled control Bcl2scr was also included.

2.2. Conjugation Using Copper-Catalyzed Azide-Alkyne Cycloaddition (CuAAC) Chemistry

The alkyne-modified ASO5.2/Bcl2 ASO.1 (20 nmol) was mixed with Folate-Peg3-Azide (100 nmol) in Milli-Q (MQ) water/DMSO/t-BuOH (2:1:1) solvent mixture with a total volume of 200 µL. Next, 10 µL of 2M triethylammonium acetate buffer (TEAA), pH = 7 was added. After degassing under argon gas, 10 µL of 10 mM Cu(II)TBTA solution and a freshly prepared solution of 4 µL of 50 mM L-ascorbic acid were added. The resulting reaction mixture was again deaerated under argon, stirred at 40 °C in the dark for 4 h and at rt in the dark for an additional 12 h. Finally, the reaction mixture was desalted and purified on a NAP5 column (GE Healthcare). The obtained solution was dried on a SpeedVac and dissolved in (MQ) water. The concentration of the product was obtained by measuring the absorbance at 260 nm. The product was characterized using IC HPLC (

Figure S5A,B,E,F) and Maldi TOF mass spectrometry (

Figure S6A,C,D).

The alkyne-modified Bcl2ss (20 nmol) was mixed with Peptide 2-azide, (P2) (20 nmol) in MQ water and 7% formamide with a total volume of 200 µL. Next, 10 µL of 2M triethylammonium acetate buffer (TEAA) and 4 µL of 50 mM aminoguanidine hydrochloride were added. After degassing under argon gas, 10 µL of 10 mM Cu(II)THPTA solution and a freshly prepared solution of 4 µL of 50 mM L-ascorbic acid were added. The resulting reaction mixture was again deaerated under argon and stirred at rt in the dark for 18 h. Finally, the reaction mixture was desalted and purified on a NAP5 column (GE Healthcare). The obtained solution was dried on a SpeedVac and dissolved in MQ water. The concentration of the product was obtained by measuring the absorbance at 260 nm. The product was characterized using IC HPLC (

Figure S5G,H) and Maldi TOF mass spectrometry (

Figure S6E,F).

The Bcl2 ASO.1-FA-P2 was synthetized by first attaching the FA to the Bcl2 ASO.1 by CuAAC, as described above. Next, we converted the amino group to an alkyne group by reaction with an alkyne NHS ester. In particular, we mixed Bcl2 ASO.1-FA (oligo amine) 20 nmol in 90 µL of 0.2 M PBS buffer, pH = 8.3 with 8 molar excess of alkyne NHS ester in 10 µL DMSO. The resulting mixture was vortexed overnight, desalted and purified using a NAP5 column (GE Healthcare). The obtained solution was dried on a SpeedVac and dissolved in MQ water. The concentration of the product was obtained by measuring the absorbance at 260 nm. The product was characterized using IC HPLC (

Figure S5I,J).

2.3. Conjugation by Disulfide Bond

To the complementary RNA oligonucleotide thiol-modified, ASOss (20 nm, 20 µL), Tris[2-carboxyethyl] phosphine (TCEP) (2000 nM, 4 µL) and 2M TEAA (5 µL) were added and the resulting mixture was stirred at rt for 4 h. Subsequently, the mixture was desalted and purified on a NAP5 column and dried on a SpeedVac. Next, the sulfhydryl RNA was redissolved in MQ/ACN (4:1) solvent in total volume of 200 µL that also contained 2M TEAA (5 µL). After the addition of 2.2’-dithio-dipyridin (200 nmol), the resulting mixture was stirred at rt for 1 h and directly purified using a NAP5 column and dried on a SpeedVac. Finally, the activated oligonucleotide was dissolved in 20 µL of MQ water, 70 µL of formamide and 5 µL of 2M TEAA. After the addition of the Peptide 1 (P1), the mixture was vortexed at rt for 3 h. The final product was purified using a NAP5 column, dried on a SpeedVac and dissolved in MQ water. The concentration of the product was obtained by measuring the absorbance at 260 nm. The product was characterized using IC HPLC (

Figure S5C,D) and Maldi TOF mass spectrometry (

Figure S6B).

2.4. Cell Culture Studies

Parental HeLa cells and HeLa cells expressing GFP were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) and a folate-free Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (pen-strep) and 2 mM L-Glutamine, kept at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. We passaged the cells twice per week.

2.5. Carrier-Free Transfection (without Lipofectamine)

For the transfection experiments, HeLa/HeLa GFP cells were first seeded into a 24-well plate at a density of 4.0 × 104 cells per well in 400 µL folate-free RPMI without pen-strep antibiotic. The next day, we added the ASOs/HDO/Scrambled control in Opti-MEM in different concentrations with a total volume of 100 µL to the cells. Accordingly, the knockdown effect of the probes was followed by fluorescence measurement over time or measured by RT-qPCR after 48 h. When applicable, the effect of the probes was also measured by flow cytometry after 48 h.

2.6. Control Transfection with Lipofectamine

HeLa and HeLa GFP cells were seeded into a 24-well plate at a density of 4.0 × 104 cells per well in 400 µL of folate-free RPMI that did not contain pen-strep antibiotic. The next day, the ASOs/HDO/Scrambled control was co-transfected using Lipofectamine 3000 following the manufacturer’s protocol. Accordingly, we followed the knockdown effect of the Lipofectamine-probes (lipoplexes) by fluorescence measurements over time or by flow cytometry after 48 h.

2.7. Fluorescence Measurement over Time

The mean fluorescence intensity of the GFP-expressing cells was followed and measured on an Incucyte Essen Bioscience instrument at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Scans of a minimum of 4 per well were made every 12 h for a total of 48 h after transfection of the ASOs. The data were analyzed using Incucyte ZOOM 2018A software.

2.8. Flow Cytometry

Post transfection/lipofectamine co-transfection (after 48 h), the cells in the wells were washed with 1× PBS followed by detachment from the culture plates (using 50 µL 0.05% trypsin with 0.02% Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)) and transferred into tubes. After centrifugation (2000 rpm for 5 min) and aspiration of the supernatant cells, the cells were suspended in 200 µL of flow cytometry (FC) buffer (1× PBS that contains 2% FBS and 3 mM EDTA). We performed flow cytometry studies immediately on a FACS Canto II instrument following the manufacturer’s protocol.

2.9. RT-qPCR

After transfection, total RNAs were isolated from the cells growing in 24-well plates. Cell lysis was performed directly in the well, using 100 μL of BL + TG buffer (Promega). The lysates from 2 wells were pooled together and total RNA was extracted using ReliaPrep™ RNA Cell Miniprep System (Promega, Z6012, Madison, WI. USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The quality and quantity of RNA were analyzed by a Thermo Scientific™ NanoDrop™ 2000 Spectrophotometer and Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Equal quantities of RNA, from each sample, were used to prepare the complementary DNA (cDNA). The reverse transcriptase reaction was performed with the Omniscript RT system (Qiagen, Germany), OligodT (Microsynth, Switzerland), and RNasin Plus RNase Inhibitor (Promega, Switzerland). The synthesis of cDNA was performed by using 6.5 µL of isolated RNA (250 ng), 1 μL of oligo-dT primer (10 μM), 1 µL of dNTP Mix (5 mM), 0.25 µL of RNase inhibitor, 0.25 µL of Omniscript reverse transcriptase (1 Unit), and 1 µL of buffer RT. The real-time PCR was performed by mixing 2 μL of 3-fold diluted cDNA with 5 μL of SYBR-green master mix (Fast SYBR Green master mix, Applied Biosystems), 2 μL of nuclease-free water (Promega, Madison, WI. USA) and 2 μL of primer mix (180 nM) on a 7500 fast real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). Relative expression levels for each gene of interest were calculated using the Pfall method [

29], with glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and tyrosine 3-monooxygenase/tryptophan 5-monooxygenase activation protein zeta (YWHAZ) as internal standard genes. Details about the primers are included in the

supplementary information (Table S2).

2.10. Cell Proliferation Assay

HeLa GFP cells were seeded into a 24-well plate at a density of 4.0 × 104 cells per well in 400 µL of folate-free RPMI without pen-strep antibiotic. The next day, the cells were transfected following the carrier-free protocol (described above) and incubated for an additional 48 h. A cell viability assay was evaluated using the CytoPainter cell proliferation staining reagent from Abcam’s (ab176736) using the manufacturer’s protocol. In short, 48 h post incubation, we washed the cells with 1× PBS, trypsinized and collected the cells into Eppendorf tubes. Next, 1× dye working solution was added and the cells were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. After removal of the dye working solution, we washed the cells with the provided buffer and prepared them for flow cytometry as described above. For the measurements, we used a red laser (633 nm) and APC filter. We analyzed the flow cytometry data using the FlowJo software v.10.

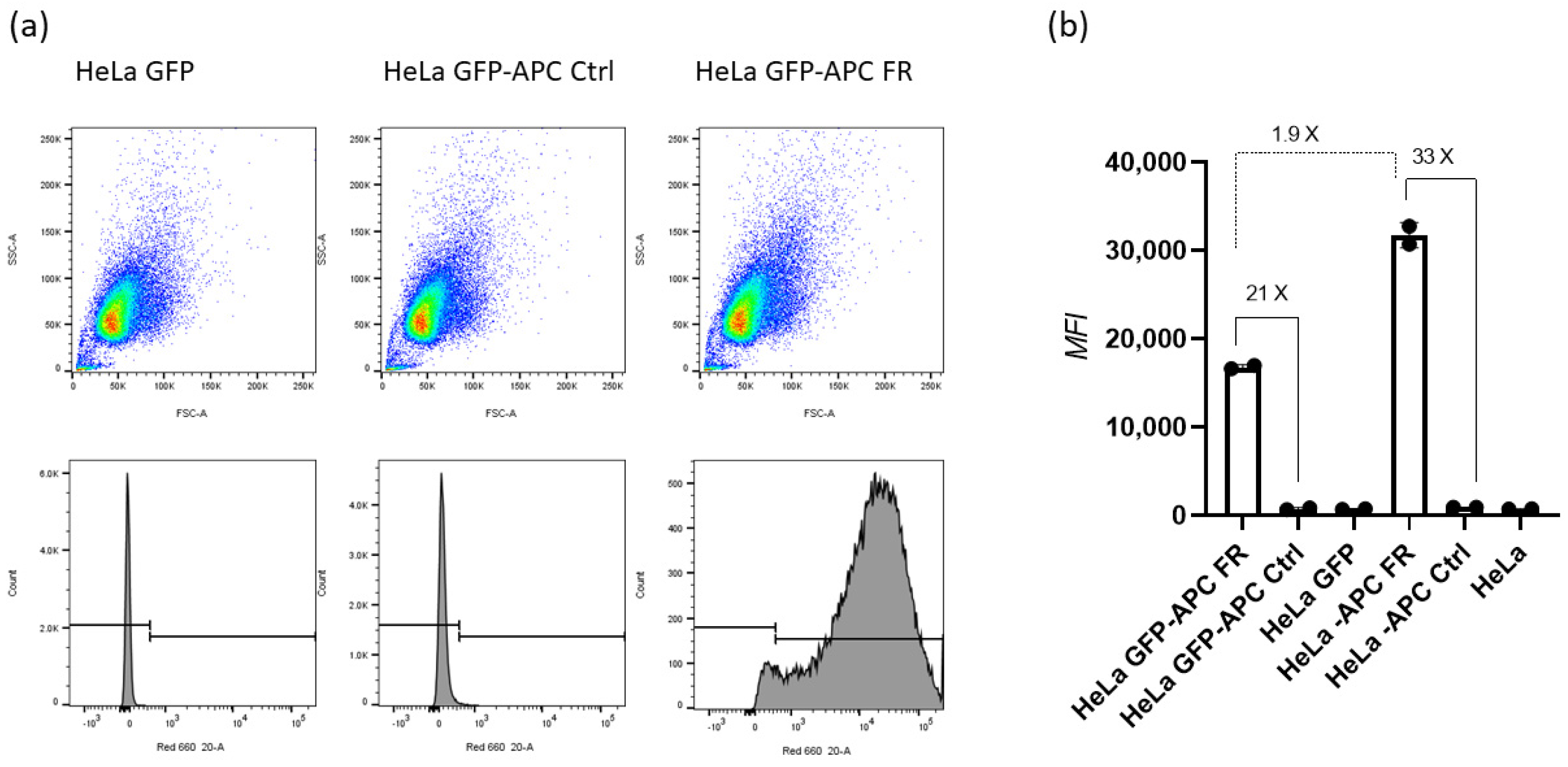

2.11. Relative Expression of the Folate-Binding Protein on the Cell Surface of HeLa and HeLa GFP Cells

For this assay we used APC anti-human Folate Receptors alpha and beta and APC Rat IgG2a, kappa Isotype Ctrl antibodies from BioLegend. HeLa/HeLa GFP cells (0.5 million per condition) were counted, placed in Eppendorf tubes and centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. Next, the medium was aspired and the cells were suspended in 50 µL of staining buffer (BioLegend). Antibodies were added to each cell suspension (5 µL per 1 million cells) and the cells were incubated in the dark, on ice for 30 min. Next, the cells were centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C followed by aspiration of the supernatant and washing with 1 mL staining buffer. The washing and centrifugation steps were repeated one more time and finally the cells were suspended in flow cytometry buffer. For the measurements, we used a red laser (633 nm) and APC filter. We analyzed the flow cytometry data using the FlowJo software v.10.

2.12. Expression of the Folate-Binding Protein on the HeLa Cells Surface

We determined the surface expression of the folate receptor in GFP HeLa cells following the previously described method [

30]. Cells were detached using trypsin, washed twice with PBS and suspended in a staining buffer (BioLegend). For the binding assay, we incubated a fixed number of 0.5 million cells per condition with increasing concentrations of antibody, APC anti-human Folate Receptors alpha and beta (0–0.5 µg) for 30 min on ice. For the depletion assay, we incubated an increasing number of cells (0.5–4 million) per condition with a fixed concentration (0.1 µg) of antibody, APC anti-human Folate Receptors alpha and beta for 30 min on ice. Next, the cells were centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C followed by aspiration of the supernatant and washing with 1 mL of staining buffer. The washing and centrifugation steps were repeated one more time and finally the cells were suspended in flow cytometry buffer. For the measurements, we used a red laser (633 nm) and APC filter. We analyzed the flow cytometry data using the FlowJo software v.10.

4. Discussion

Herein we investigated the ability for targeted intracellular delivery of multi-modified and multi-functionalized HDOs. These advanced HDOs consisted of a modified antisense strand (ASO) that bore a triazole internally linked folic acid and a pure RNA/DNA sense strand decorated with a short peptide sequence on the 3’ termini. We have shown that the HDO conjugated with folic acid and peptide can efficiently silence GFP and Bcl2 genes in GFP-expressing and wild-type HeLa cells, respectively.

We first rationally designed the oligonucleotides forming the HDO and selected the ligand and the peptide sequence. For the GFP HDO, the ASO was chemically modified to contain phosphorothioate instead of a natural phosphodiester backbone and terminal 2’OMe sugar modifications on both termini, 3′ and 5′, giving the possibility for both RNase H or steric blocking mechanisms of action. Previous reports show that phosphorothioate-modified oligonucleotides possess higher resistance towards extra- and intracellular degradation by nucleases and assist cellular uptake and bioavailability in vivo [

31]. Further, Hoon Yoo et al. demonstrated that 2’OMe sugar modifications do not show toxic effects and they are resistant to serum nucleases [

32]. Moreover, the ASO bears an internal triazole-linked folic acid. We chose folic acid as a specific ligand to target the folate receptor expressed at the HeLa cell surface. Fernandez et al. reported that the folate receptor was 100–300 times overexpressed (on the order of 1–10 million receptor copies per cell) in ovarian cancer compared with normal cells [

33]. Our results of approximately 1.7 million receptor copies per HeLa cell are in this order of magnitude and confirm the sufficient expression of the folate receptor to be used for targeted delivery by the folic acid ligand. We used CuAAC chemistry to attach the folic acid azide to the ASO alkyne because of its selectivity and ability to give products in high purity and yields [

34,

35]. In regards to ASOss, we designed it as a pure RNA sequence conjugated with P1 via a disulfide bond [

36,

37]. The rationale behind this choice is that the disulfide bond can be reduced in the endosomes and the peptide can thereby detach from the GFP HDO [

38].

We designed the Bcl2 ASO.1 representing the active part of the Bcl2 HDO to follow the same structural modifications and folic acid label as the ASO in GFP HDO. However, the Bcl2 ASO.1 contains an additional amino functionality on the 5’terminus that opens the possibility of an additional attachment of P2 by CuAAC chemistry. On the other hand, we designed the Bcl2ss as a pure DNA sequence and conjugated it via CuAAC chemistry to P2.

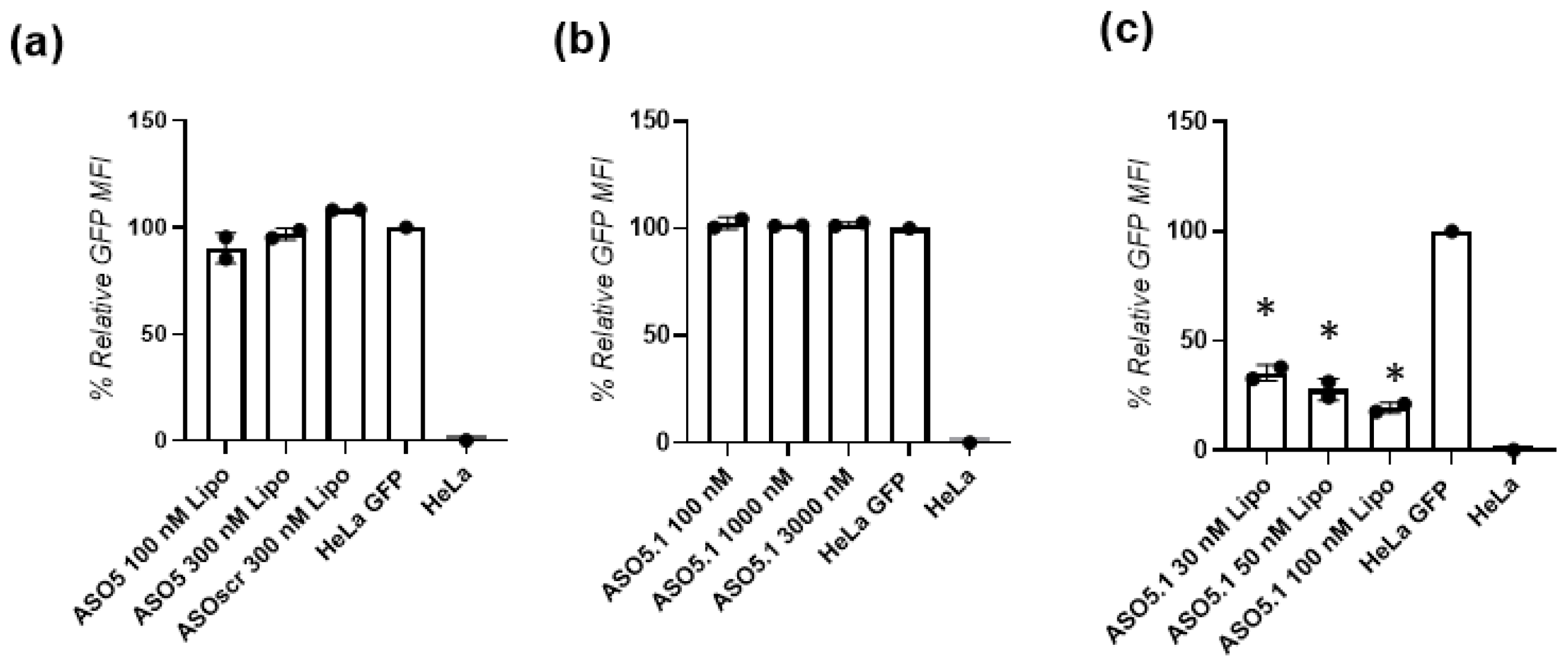

First, we assessed the parent ASOs (pure DNA sequences, ASO1–ASO6) for their ability to perform GFP gene silencing in GFP-expressing HeLa cells. The data show insignificant gene silencing even when transfected with Lipo. Since ASO5 presented a minor gene silencing effect (10%), we upgraded it to a modified sequence named ASO5.1. While the ASO5.1 with high 3000 nM carrier-free transfection failed to show biological activity, the same sequence, when transfected with Lipo in 100 nM concentrations, showed efficient gene silencing by 80%. These results confirm that while the advanced modified version sequence -ASO5.1 is capable for proficient GFP gene knockdown, it still lacks the ability of intracellular delivery without the transfection agent Lipo. This observation is in agreement with previous reports confirming that in contrast to natural DNA and RNA sequences, modified oligonucleotides are resistant to enzymatic degradation and can stay intact in biological media to perform gene knockdown [

7].

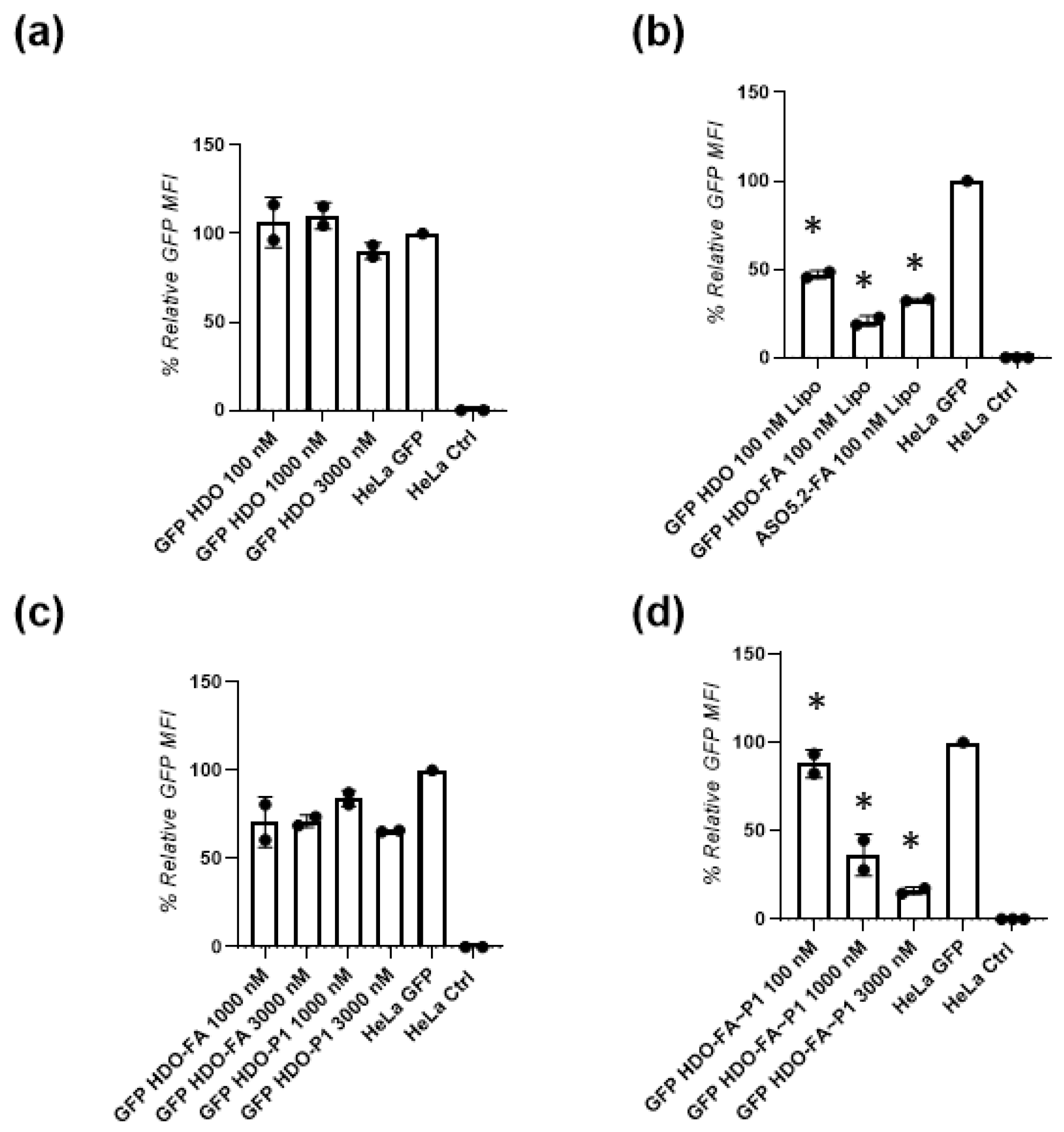

Next, we show that the GFP HDO (not conjugated with the biomolecules) when transfected with Lipo, showed efficient gene silencing by 53%. However, the same GFP HDO transfected without Lipo lacked the ability to perform GFP gene silencing. This result confirms that we have successfully designed the GFP HDO to perform gene knockdown but that it lacks the ability for intracellular delivery. When the GFP HDO was conjugated with folic acid to result in GFP HDO-FA and then transfected with Lipo, the biological effect was superior (80% gene knock down). This result suggests that the centrally installed folic acid can increase the silencing activity of this new HDO. Recently Salim et al. reported on the gene-silencing activity of siRNA bearing folic acid modifications at different positions within the sense strand [

39]. The authors showed that compared with siRNA modified on the termini, centrally modified folic acid siRNA enabled 80% gene silencing after treatment with 750 nM concentrations. Another report suggests that a centrally introduced mismatches in the structure of siRNA or double-stranded ASOs increases their biological efficacy and reduces toxicity [

39,

40]. A reasonable explanation for this effect is that the double-stranded oligonucleotides shall first dissociate, or the sense strand should be degraded by cellular enzymes, prior to hybridization to the target mRNA and performance of its mRNA knockdown action. On the other hand, the advanced parent oligonucleotide ASO5.2-FA when transfected with Lipo in the same concentrations showed a lower silencing effect (64%) compared with GFP HDO-FA. These results are in agreement with previous reports where double-stranded heteroduplex oligonucleotide showed higher knockdown compared with its single-stranded parent ASO [

19,

20,

22,

41].

Next, we tested the GFP HDOs conjugated only with folic acid, only with P1 or both biomolecules without Lipo transfection. Both GFP HDO-FA and GFP HDO-P1 showed intermediate gene silencing efficiencies by 30% and by 35%, respectively after 3000 nM treatment. Nevertheless, treatment with GFP HDO-FA-P1, bearing both attachments, the folic acid and the peptide sequence, at the same 3000 nM concentration led to 84% GFP gene knockdown. This improvement in the biological activity is significant and shows the importance of the additional effect of the attached folic acid and peptide. Fernandez et al. reported that the folic acid is a specific ligand for the folate receptor that is overexpressed in variety of cancer cells [

33]. In addition, the benefit of a ligand–receptor interaction for the targeted intracellular delivery of oligonucleotide therapeutics is well known, [

42] and the ability of folic acid to enhance the intracellular delivery through ligand-receptor endocytosis is studied [

43]. Nevertheless, in the case of oligonucleotide therapeutics, recent reports highlight the importance of endosomal escape after delivery through endocytosis [

44]. To perform its action after intracellular delivery, it is vital for the ASOs or siRNA to escape the endosomes and to be released in unrestricted form into the cytoplasm. Considering this, we designed the peptides, P1 and P2 to contain a cell-penetrating domain (CPD) (classical tat peptide) and an endosome escaping domain (EED) [

45]. While the CPD favors crossing the cellular membrane, the EED plays a role in bursting the endosomal membrane and releasing the product into the cytoplasm. To our knowledge, there are no other reports in the literature that have examined the gene silencing activity of similar designs of advanced HDOs.

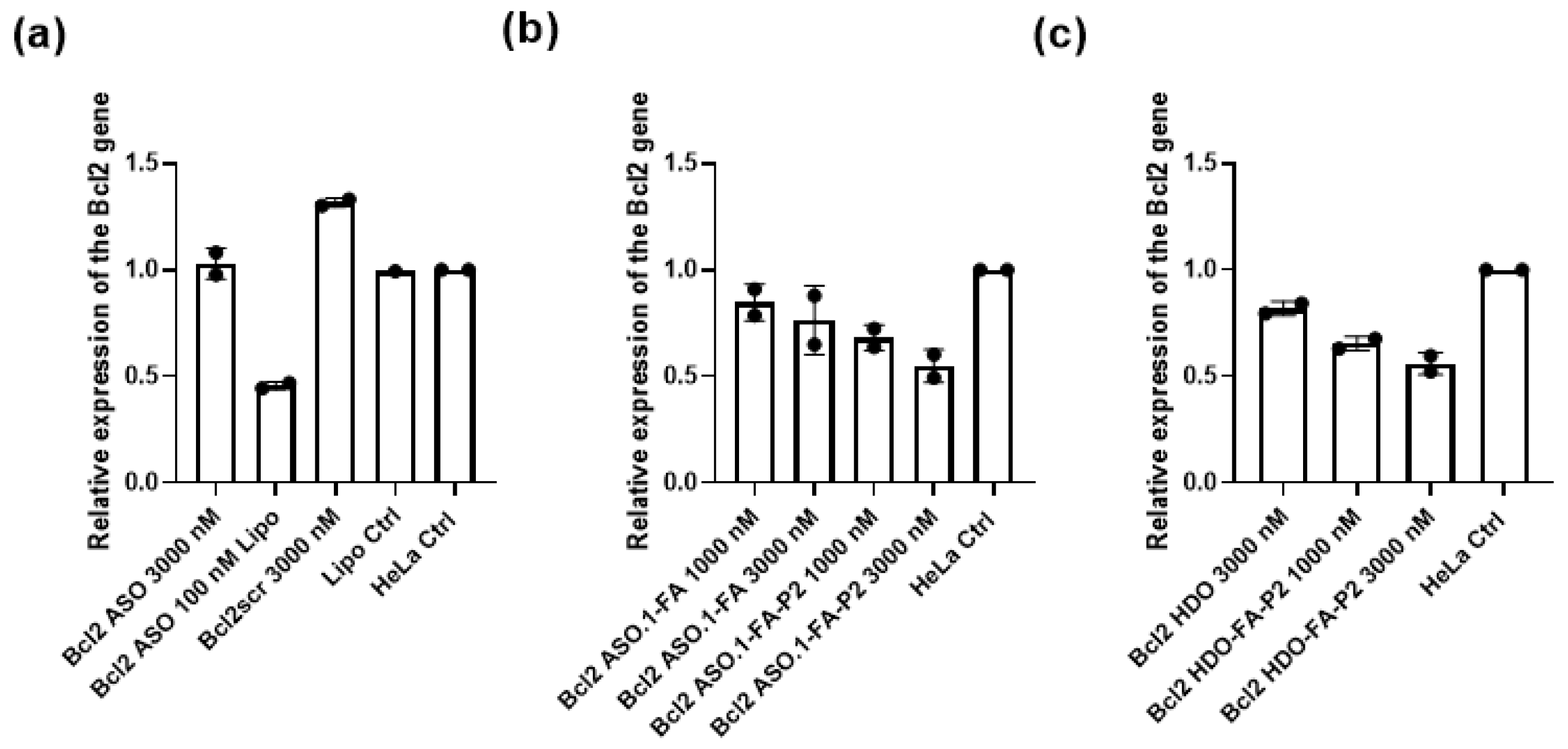

Finally, to check the biological action of the new HDO, we confirmed the gene-silencing activity of the endogenous Bcl2 gene using real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) in HeLa cells. Compared with the unconjugated Bcl2 HDO, the Bcl2 HDO-FA-P2 showed efficient by 44% Bcl2 gene silencing. This result confirms that the folic acid and the P2 attachment improve intracellular delivery and the endosomal escape. Additionally, when we decorated the single-stranded parent ASO with both folic acid and P2 to yield Bcl2 ASO.1-FA-P2 it showed similar gene-silencing efficacy (by 46%) to the Bcl2 HDO-FA-P2, proving that the multi-labeled strategy might work for single-stranded ASOs. Since the multi-labeling process of single-stranded ASOs is challenging, further development of new chemical strategies will likely lead to simplified and cost-efficient synthesis that will inspire future systematic testing in vivo.