Thiourea Organocatalysts as Emerging Chiral Pollutants: En Route to Porphyrin-Based (Chir)Optical Sensing

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

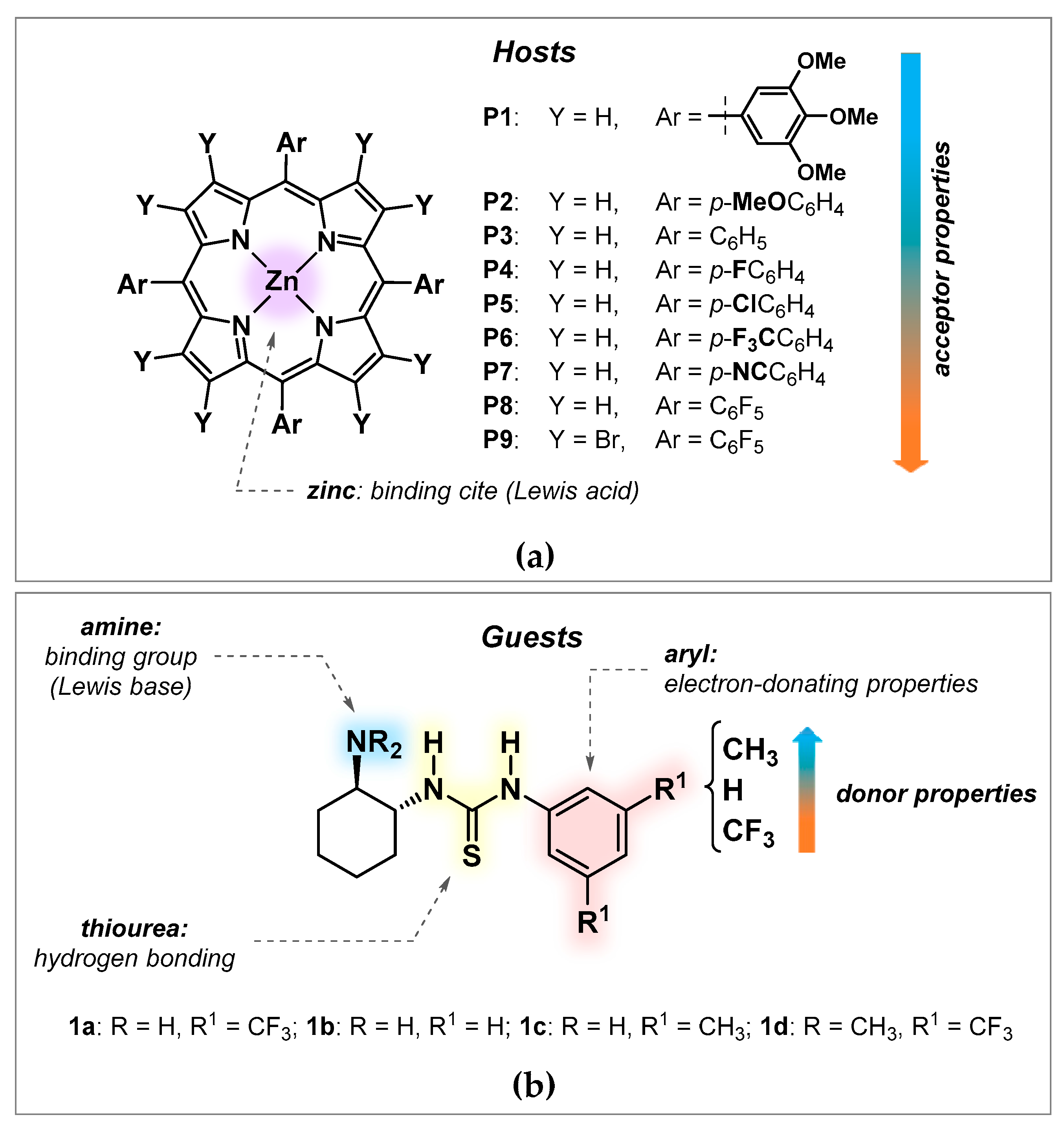

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Toxicity Studies

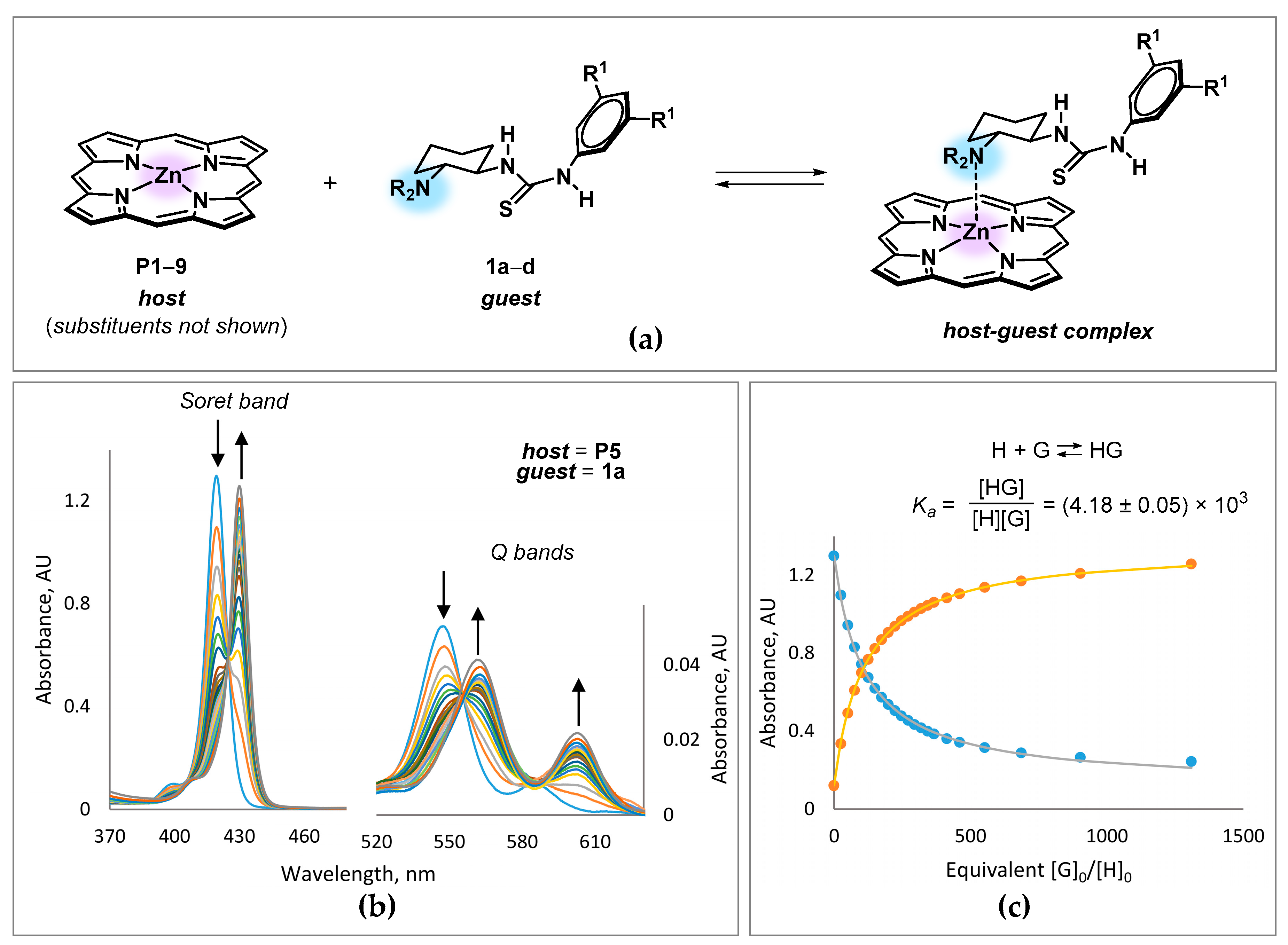

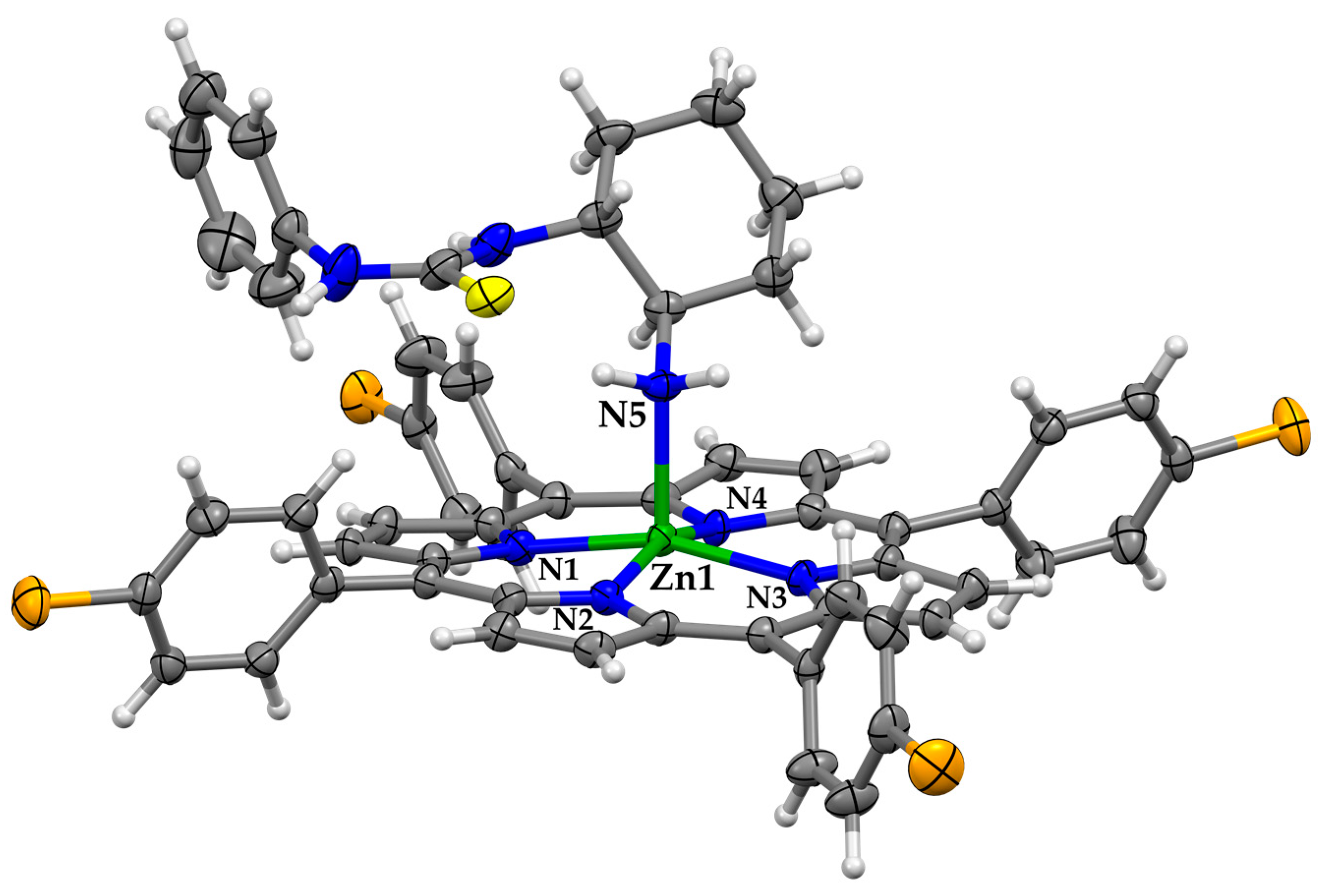

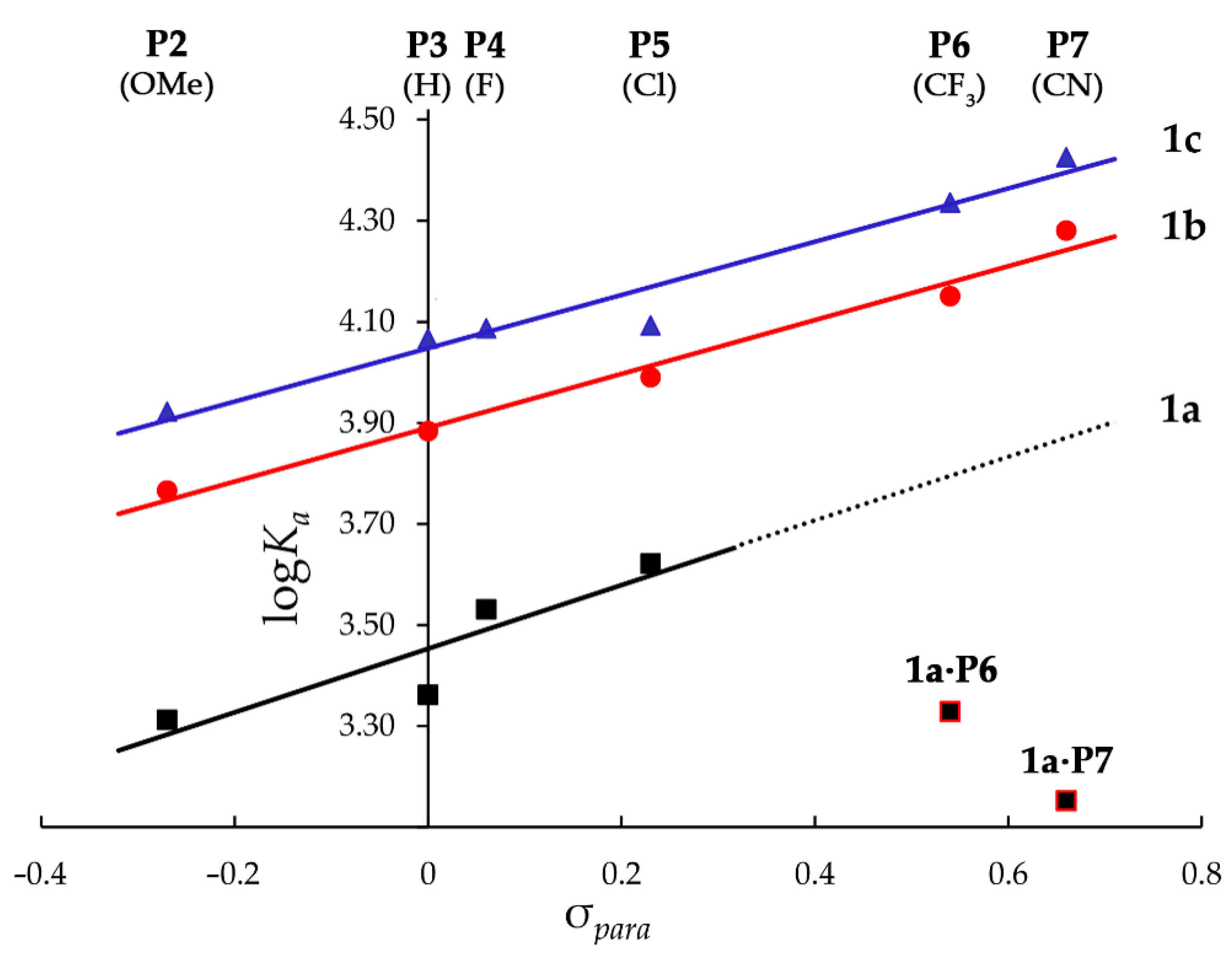

3.2. Binding and Structural Studies

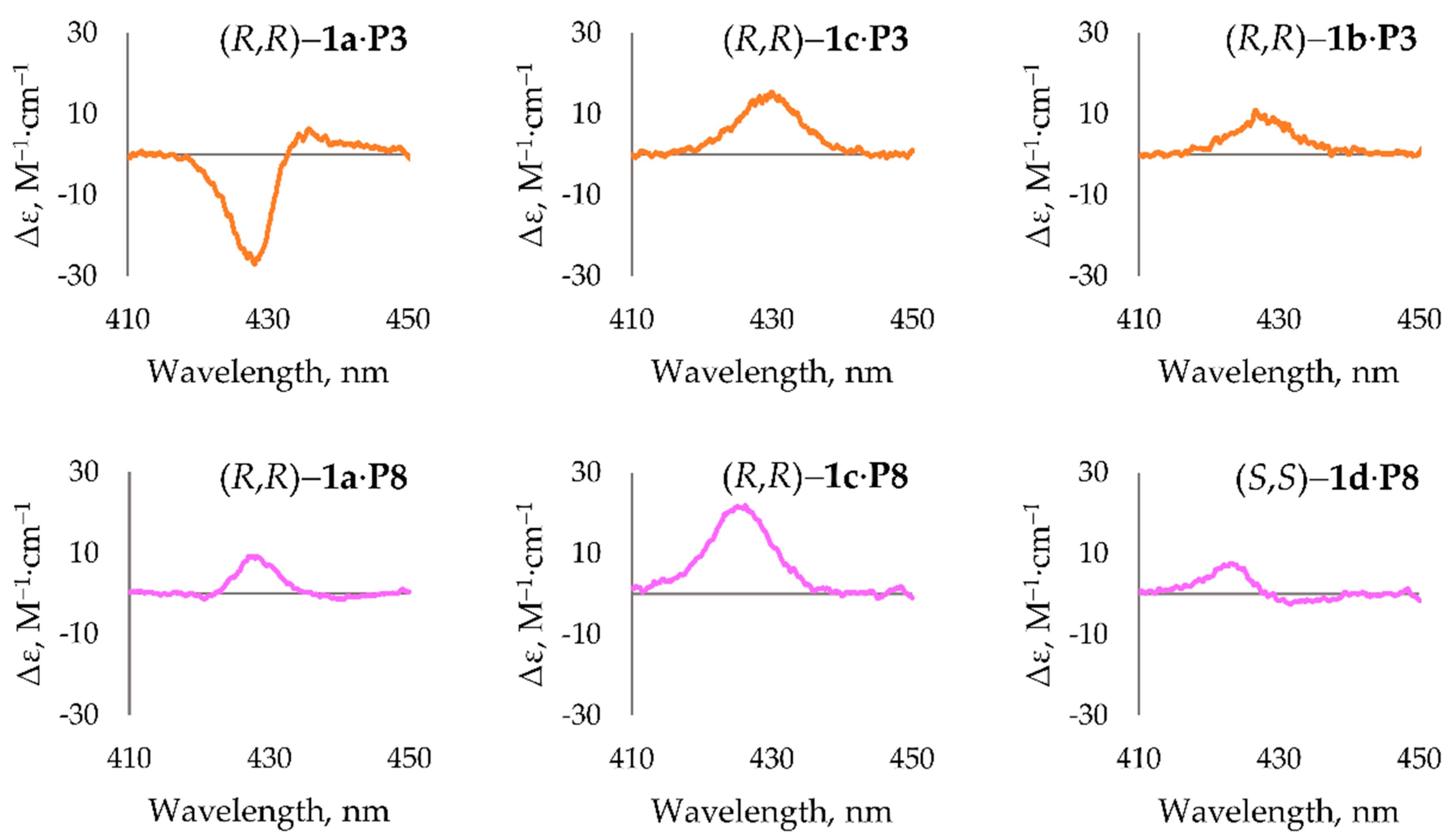

3.3. Circular Dichroism Spectra

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jeschke, P. Current status of chirality in agrochemicals. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2018, 74, 2389–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaser, H.-U. Chirality and its implications for the pharmaceutical industry. Rend. Lincei 2013, 24, 213–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agranat, I.; Wainschtein, S.R.; Zusman, E.Z. The predicated demise of racemic new molecular entities is an exaggeration. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2012, 11, 972–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kasprzyk-Hordern, B. Pharmacologically active compounds in the environment and their chirality. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 4466–4503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sanganyado, E.; Lu, Z.; Fu, Q.; Schlenk, D.; Gan, J. Chiral pharmaceuticals: A review on their environmental occurrence and fate processes. Water Res. 2017, 124, 527–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kümmerer, K. Pharmaceuticals in the Environment; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, E.; Wick, A.; Ternes, T.A.; Coors, A. Ecotoxicity of climbazole, a fungicide contained in antidandruff shampoo. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2013, 32, 2816–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maia, A.S.; Ribeiro, A.R.; Castro, P.M.L.; Tiritan, M.E. Chiral analysis of pesticides and drugs of environmental concern: Biodegradation and enantiomeric fraction. Symmetry 2017, 9, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ulrich, E.M.; Morrison, C.N.; Goldsmith, M.R.; Foreman, W.T. Chiral pesticides: Identification, description, and environmental implications. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2012, 217, 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- You, L.; Zha, D.; Anslyn, E.V. Recent advances in supramolecular analytical chemistry using optical sensing. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 7840–7892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mako, T.L.; Racicot, J.M.; Levine, M. Supramolecular luminescent sensors. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 322–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minami, T. Design of Supramolecular sensors and their applications to optical chips and organic devices. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2020, 94, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolesse, R.; Nardis, S.; Monti, D.; Stefanelli, M.; Di Natale, C. Porphyrinoids for chemical sensor applications. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 2517–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hembury, G.A.; Borovkov, V.V.; Inoue, Y. Chirality-sensing supramolecular systems. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 1–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borovkov, V.V.; Lintuluoto, J.M.; Inoue, Y. Supramolecular chirogenesis in bis (zinc porphyrin): An absolute configuration probe highly sensitive to guest structure. Org. Lett. 2000, 2, 1565–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lintuluoto, J.M.; Borovkov, V.V.; Inoue, Y. Direct determination of absolute configuration of monoalcohols by bis (magnesium porphyrin). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 13676–13677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeda, S.; Hayashi, S.; Noji, M.; Takanami, T. Chiroptical protocol for the absolute configurational assignment of Alkyl-substituted epoxides using bis (zinc porphyrin) as a CD-sensitive bidentate host. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielewski, P.J.; Siczek, M.; Stępień, M. Bis (N-Confused Porphyrin) as a semirigid receptor with a chirality memory: A two-way host enantiomerization through point-to-axial chirality transfer. Chem.-A Eur. J. 2015, 21, 2547–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gholami, H.; Chakraborty, D.; Zhang, J.; Borhan, B. Absolute stereochemical determination of organic molecules through induction of helicity in host–guest complexes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 654–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamberth, C. Heterocyclic chemistry in crop protection. Pest Manag. Sci. 2013, 69, 1106–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertl, P.; Altmann, E.; McKenna, J.M. The most common functional groups in bioactive molecules and how their popularity has evolved over time. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 8408–8418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerru, N.; Gummidi, L.; Maddila, S.; Gangu, K.K.; Jonnalagadda, S.B. A review on recent advances in nitrogen-containing molecules and their biological applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borovkov, V.V.; Lintuluoto, J.M.; Sugeta, H.; Fujiki, M.; Arakawa, R.; Inoue, Y. Supramolecular chirogenesis in zinc porphyrins: Equilibria, binding properties, and thermodynamics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 2993–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, S.; Hiroto, S.; Ousaka, N.; Yashima, E.; Shinokubo, H. Control of conformation and chirality of nonplanar π-conjugated diporphyrins using substituents and axial ligands. Chem.-Asian J. 2016, 11, 936–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsson, S.; Schäfer, C.; Blom, M.; Gogoll, A. Exciton-coupled circular dichroism characterization of monotopically binding guests in host−guest complexes with a bis (zinc porphyrin) tweezer. Chempluschem 2018, 83, 1169–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizutani, T.; Ema, T.; Yoshida, T.; Renne, T.; Ogoshi, H. Mechanism of induced circular dichroism of amino acid ester-porphyrin supramolecular systems. Implications to the origin of the circular dichroism of hemoprotein. Inorg. Chem. 1994, 33, 3558–3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizutani, T.; Kurahashi, T.; Murakami, T.; Matsumi, N.; Ogoshi, H. Molecular recognition of carbohydrates by zinc porphyrins: Lewis acid/lewis base combinations as a dominant factor for their selectivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 8991–9001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, H.; Munakata, H.; Uemori, Y.; Sakura, N. Chiral recognition of amino acids and dipeptides by a water-soluble zinc porphyrin. Inorg. Chem. 2004, 43, 1211–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomollón-Bel, F. Ten chemical innovations that will change our world: IUPAC identifies emerging technologies in Chemistry with potential to make our planet more sustainable. Chem. Int. 2019, 41, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, P.R.; Wittkopp, A. H-bonding additives act like lewis acid catalysts. Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigman, M.S.; Jacobsen, E.N. Schiff base catalysts for the asymmetric strecker reaction identified and optimized from parallel synthetic libraries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 4901–4902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okino, T.; Hoashi, Y.; Takemoto, Y. Enantioselective Michael reaction of malonates to nitroolefins catalyzed by bifunctional organocatalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 12672–12673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serdyuk, O.V.; Heckel, C.M.; Tsogoeva, S.B. Bifunctional primary amine-thioureas in asymmetric organocatalysis. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013, 11, 7051–7071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Steppeler, F.; Iwan, D.; Wojaczyńska, E.; Wojaczyński, J. Chiral thioureas—preparation and significance in asymmetric synthesis and medicinal chemistry. Molecules 2020, 25, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Takemoto, Y. Recognition and activation by ureas and thioureas: Stereoselective reactions using ureas and thioureas as hydrogen-bonding donors. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2005, 3, 4299–4306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limnios, D.; Kokotos, C.G. Chapter 19 ureas and thioureas as asymmetric organocatalysts. In Sustainable Catalysis: Without Metals or Other Endangered Elements, Part 2; The Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2015; pp. 196–255. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, R.C.; Lohmeijer, B.G.G.; Long, D.A.; Lundberg, P.N.P.; Dove, A.P.; Li, H.; Wade, C.G.; Waymouth, R.M.; Hedrick, J.L. Exploration, optimization, and application of supramolecular thiourea−amine catalysts for the synthesis of lactide (Co) polymers. Macromolecules 2006, 39, 7863–7871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamber, N.E.; Jeong, W.; Waymouth, R.M.; Pratt, R.C.; Lohmeijer, B.G.G.; Hedrick, J.L. Organocatalytic ring-opening polymerization. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 5813–5840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhan, B.; Tschan, M.J.-L.; Wirotius, A.-L.; Dove, A.P.; Coulembier, O.; Taton, D. Isoselective ring-opening polymerization of rac-lactide from Chiral Takemoto’s organocatalysts: Elucidation of stereocontrol. ACS Macro Lett. 2018, 7, 1413–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- SciFinder database. Available online: https://scifinder.cas.org/ (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- Egorova, K.S.; Ananikov, V.P. Which metals are green for catalysis? Comparison of the toxicities of Ni, Cu, Fe, Pd, Pt, Rh, and au salts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 12150–12162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egorova, K.S.; Ananikov, V.P. Toxicity of metal compounds: Knowledge and myths. Organometallics 2017, 36, 4071–4090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hayes, T. Green Organocatalysis: An (eco)-Toxicity and Biodegradation Study of Organocatalysts; Dublin City University: Dublin, Ireland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nachtergael, A.; Coulembier, O.; Dubois, P.; Helvenstein, M.; Duez, P.; Blankert, B.; Mespouille, L. Organocatalysis paradigm revisited: Are metal-free catalysts really harmless? Biomacromolecules 2015, 16, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortimer, M.; Kasemets, K.; Heinlaan, M.; Kurvet, I.; Kahru, A. High throughput kinetic Vibrio fischeri bioluminescence inhibition assay for study of toxic effects of nanoparticles. Toxicol. Vitr. 2008, 22, 1412–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudziński, K.; Pakulska, A.M.; Kwiatkowski, P. An efficient organocatalytic method for highly enantioselective michael addition of malonates to enones catalyzed by readily accessible primary amine-thiourea. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 4222–4225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.-J.; Liu, S.-P.; Lao, J.-H.; Du, G.-J.; Yan, M.; Chan, A.S. Asymmetric conjugate addition of carbonyl compounds to nitroalkenes catalyzed by chiral bifunctional thioureas. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2009, 20, 1451–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borovkov, V.V.; Lintuluoto, J.M.; Inoue, Y. Synthesis of Zn-, Mn-, and Fe-containing mono- and heterometallated ethanediyl-bridged porphyrin dimers. Helv. Chim. Acta 1999, 82, 919–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, T.; Nakanishi, T.; Honda, T.; Harada, R.; Shiro, M.; Fukuzumi, S. Impact of distortion of porphyrins on axial coordination in (Porphyrinato) zinc (II) complexes with aminopyridines as axial ligands. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 2009, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandon, D.; Ochenbein, P.; Fischer, J.; Weiss, R.; Jayaraj, K.; Austin, R.N.; Gold, A.; White, P.S.; Brigaud, O. beta.-Halogenated-pyrrole porphyrins. Molecular structures of 2,3,7,8,12,13,17,18-octabromo-5,10,15,20-tetramesitylporphyrin, nickel (II) 2,3,7,8,12,13,17,18-octabromo-5,10,15,20-tetramesitylporphyrin, and nickel (II) 2,3,7,8,12,13,17,18-octabromo-5,10,15. Inorg. Chem. 1992, 31, 2044–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Online Tools for Supramolecular Chemistry Research and Analysis. Available online: http://supramolecular.org/ (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Brynn Hibbert, D.; Thordarson, P. The death of the Job plot, transparency, open science and online tools, uncertainty estimation methods and other developments in supramolecular chemistry data analysis. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 12792–12805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hirose, K. A practical guide for the determination of binding constants. J. Incl. Phenom. Macrocycl. Chem. 2001, 39, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehnherr, D.; Ford, D.D.; Bendelsmith, A.J.; Rose Kennedy, C.; Jacobsen, E.N. Conformational control of chiral amido-thiourea catalysts enables improved activity and enantioselectivity. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 3214–3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nogales, D.F.; Ma, J.-S.; Lightner, D.A. Self-association of dipyrrinones observed by 2d-noe nmr and dimerization constants calculated from 1h-nmr chemical shifts. Tetrahedron 1993, 49, 2361–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigaku Oxford Diffraction, CrysAlisPro Software System; Version 38.46; Rigaku Corporation Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2017.

- Sheldrick, G.M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 2008, 64, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXL13. Program Package for Crystal Structure Determination from Single Crystal Diffraction Data; University of Göttingen: Göttingen, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konrad, N.; Meniailava, D.; Osadchuk, I.; Adamson, J.; Hasan, M.; Clot, E.; Aav, R.; Borovkov, V.; Kananovich, D. Supramolecular chirogenesis in zinc porphyrins: Complexation with enantiopure thiourea derivatives, binding studies and chirality transfer mechanism. J. Porphyr. Phthalocyanines 2019, 24, 840–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichkorn, K.; Treutler, O.; Öhm, H.; Häser, M.; Ahlrichs, R. Auxiliary basis sets to approximate Coulomb potentials. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1995, 240, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichkorn, K.; Weigend, F.; Treutler, O.; Ahlrichs, R. Auxiliary basis sets for main row atoms and transition metals and their use to approximate Coulomb potentials. Theor. Chem. Acc. 1997, 97, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierka, M.; Hogekamp, A.; Ahlrichs, R. Fast evaluation of the Coulomb potential for electron densities using multipole accelerated resolution of identity approximation. J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 118, 9136–9148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becke, A.D. Density-functional exchange-energy approximation with correct asymptotic behavior. Phys. Rev. A 1988, 38, 3098–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.P. Density-functional approximation for the correlation energy of the inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. B 1986, 33, 8822–8824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimme, S.; Antony, J.; Ehrlich, S.; Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schäfer, A.; Horn, H.; Ahlrichs, R. Fully optimized contracted Gaussian basis sets for atoms Li to Kr. J. Chem. Phys. 1992, 97, 2571–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TURBOMOLE V7.0 2015, a Development of University of Karlsruhe and Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe GmbH, 1089–2007, TURBOMOLE GmbH, Since 2007. Available online: http://www.turbomole.com (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- Osadchuk, I.; Borovkov, V.; Aav, R.; Clot, E. Benchmarking computational methods and influence of guest conformation on chirogenesis in zinc porphyrin complexes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 11025–11037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martynov, A.G.; Mack, J.; May, A.K.; Nyokong, T.; Gorbunova, Y.G.; Tsivadze, A.Y. Methodological survey of simplified TD-DFT methods for fast and accurate interpretation of UV-Vis–NIR spectra of phthalocyanines. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 7265–7284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, N.; Fink, R.; Hieringer, W. Assignment of near-edge x-ray absorption fine structure spectra of metalloporphyrins by means of time-dependent density-functional calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 133, 054703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigend, F. Accurate Coulomb-fitting basis sets for H to Rn. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2006, 8, 1057–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andzelm, J.; Kölmel, C.; Klamt, A. Incorporation of solvent effects into density functional calculations of molecular energies and geometries. J. Chem. Phys. 1995, 103, 9312–9320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, R.F.W. Atoms in molecules. Acc. Chem. Res. 1985, 18, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, R.F.W. A quantum theory of molecular structure and its applications. Chem. Rev. 1991, 91, 893–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, T.A. AIMAll; Version 19.10.12; Gristmill Software: Overland Park KS, USA, 2019; Available online: aim.tkgristmill.com (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- Reed, A.E.; Curtiss, L.A.; Weinhold, F. Intermolecular interactions from a natural bond orbital, donor-acceptor viewpoint. Chem. Rev. 1988, 88, 899–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinhold, F. Nature of H-bonding in clusters, liquids, and enzymes: An ab initio, natural bond orbital perspective. J. Mol. Struct. THEOCHEM 1997, 398–399, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glendening, E.D.; Reed, A.E.; Carpenter, J.E.; Weinhold, F. NBO, Version 3.1; Available online: https://gaussian.com/citation/ (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16, Revision B.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016; Available online: https://gaussian.com/citation_b01/ (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- Chai, J.-D.; Head-Gordon, M. Long-range corrected hybrid density functionals with damped atom–atom dispersion corrections. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008, 10, 6615–6620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dunning, T.H. Gaussian basis sets for use in correlated molecular calculations. I. The atoms boron through neon and hydrogen. J. Chem. Phys. 1989, 90, 1007–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, R.A.; Dunning, T.H.; Harrison, R.J. Electron affinities of the first-row atoms revisited. Systematic basis sets and wave functions. J. Chem. Phys. 1992, 96, 6796–6806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Woon, D.E.; Dunning, T.H. Gaussian basis sets for use in correlated molecular calculations. III. The atoms aluminum through argon. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 1358–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marenich, A.V.; Cramer, C.J.; Truhlar, D.G. Universal solvation model based on solute electron density and on a continuum model of the solvent defined by the bulk dielectric constant and atomic surface tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 6378–6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennington, R.; Keith, T.A.; Millam, J.M. GaussView, Version 6; Semichem Inc.: Shawnee Mission, KS, USA. Available online: https://gaussian.com/citation/ (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- ISO. Water Quality—Kinetic Determination of the Inhibitory Effects of Sediment, Other Solids and Coloured Samples on the Light Emission of Vibrio fischeri (Kinetic Luminescent Bacteria Test); ISO 21338: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Vindimian, E. REGTOX: Macro ExcelTM pour dose-réponse. Available online: http://www.normalesup.org/~vindimian/en_index.html (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- Kahru, A. In vitro toxicity testing using marine luminescent bacteria (Photobacterium phosphoreum): The BiotoxTM test. Altern. Lab. Anim. 1993, 21, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumahastuti, D.K.A.; Sihtmäe, M.; Kapitanov, I.V.; Karpichev, Y.; Gathergood, N.; Kahru, A. Toxicity profiling of 24 l-phenylalanine derived ionic liquids based on pyridinium, imidazolium and cholinium cations and varying alkyl chains using rapid screening Vibrio fischeri bioassay. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 172, 556–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahru, A.; Põllumaa, L. Environmental hazard of the waste streams of Estonian oil shale industry: An ecotoxicological review. Oil Shale 2006, 23, 53–93. [Google Scholar]

- Aruoja, V.; Sihtmäe, M.; Dubourguier, H.-C.; Kahru, A. Toxicity of 58 substituted anilines and phenols to algae Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata and bacteria Vibrio fischeri: Comparison with published data and QSARs. Chemosphere 2011, 84, 1310–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurvet, I.; Ivask, A.; Bondarenko, O.; Sihtmäe, M.; Kahru, A. LuxCDABE—Transformed constitutively bioluminescent escherichia coli for toxicity screening: Comparison with naturally luminous vibrio fischeri. Sensors 2011, 11, 7865–7878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilhelm, E.A.; Jesse, C.R.; Nogueira, C.W.; Savegnago, L. Introduction of trifluoromethyl group into diphenyl diselenide molecule alters its toxicity and protective effect against damage induced by 2-nitropropane in rats. Exp. Toxicol. Pathol. 2009, 61, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Deng, H.; Zhang, B.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Luo, S.; Cheng, J.-P. Physical organic study of structure–activity–enantioselectivity relationships in asymmetric bifunctional thiourea catalysis: Hints for the design of new organocatalysts. Chem.-A Eur. J. 2010, 16, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippert, K.M.; Hof, K.; Gerbig, D.; Ley, D.; Hausmann, H.; Guenther, S.; Schreiner, P.R. Hydrogen-bonding thiourea organocatalysts: The privileged 3,5-bis (trifluoromethyl)phenyl group. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 2012, 5919–5927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakab, G.; Tancon, C.; Zhang, Z.; Lippert, K.M.; Schreiner, P.R. (Thio) urea organocatalyst equilibrium acidities in DMSO. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 1724–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreienborg, N.M.; Merten, C. How do substrates bind to a bifunctional thiourea catalyst? A vibrational CD study on carboxylic acid binding. Chem.-A Eur. J. 2018, 24, 17948–17954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, C.R.; Iverson, B.L. Rethinking the term “pi-stacking”. Chem. Sci. 2012, 3, 2191–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jentzen, W.; Song, X.-Z.; Shelnutt, J.A. Structural characterization of synthetic and protein-bound porphyrins in terms of the lowest-frequency normal coordinates of the macrocycle. J. Phys. Chem. B 1997, 101, 1684–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsbury, C.J.; Senge, M.O. The shape of porphyrins. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 431, 213760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NSD On-line Tool. Available online: https://www.kingsbury.id.au/nsd (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- Király, P.; Soós, T.; Varga, S.; Vakulya, B.; Tárkányi, G. Self-association promoted conformational transition of (3R,4S,8R,9R)-9-[(3,5-bis (trifluoromethyl) phenyl))-thiourea] (9-deoxy)-epi-cinchonine. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2010, 48, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obrzud, M.; Rospenk, M.; Koll, A. Structure of aggregates of dialkyl urea derivatives in solutions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114, 15905–15912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obrzud, M.; Rospenk, M.; Koll, A. Self-aggregation mechanisms of N-alkyl derivatives of urea and thiourea. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 3209–3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.B.; Rho, H.S.; Oh, J.S.; Nam, E.H.; Park, S.E.; Bae, H.Y.; Song, C.E. DOSY NMR for monitoring self aggregation of bifunctional organocatalysts: Increasing enantioselectivity with decreasing catalyst concentration. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2010, 8, 3918–3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansch, C.; Leo, A.; Taft, R.W. A survey of Hammett substituent constants and resonance and field parameters. Chem. Rev. 1991, 91, 165–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majerz, I.; Dziembowska, T. Aromaticity and through-space interaction between aromatic rings in [2.2] paracyclophanes. J. Phys. Chem. A 2016, 120, 8138–8147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majerz, I.; Dziembowska, T. Substituent effect on inter-ring interaction in paracyclophanes. Mol. Divers. 2020, 24, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caramori, G.F.; Galembeck, S.E. Computational study about through-bond and through-space interactions in [2.2] cyclophanes. J. Phys. Chem. A 2007, 111, 1705–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinnokrot, M.O.; Sherrill, C.D. Substituent effects in π−π interactions: Sandwich and T-shaped configurations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 7690–7697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, S.; Sugibayashi, Y.; Nakanishi, W. Quantum chemical calculations with the AIM approach applied to the π-interactions between hydrogen chalcogenides and naphthalene. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 49651–49660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roucan, M.; Kielmann, M.; Connon, S.J.; Bernhard, S.S.R.; Senge, M.O. Conformational control of nonplanar free base porphyrins: Towards bifunctional catalysts of tunable basicity. Chem. Commun. 2017, 54, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Marsh, R.E.; Schaefer, W.P.; Hodge, J.A.; Hughes, M.E.; Gray, H.B.; Lyons, J.E.; Ellis Jnr, P.E. A highly solvated zinc (II) tetrakis (pentafluorophenyl)-β-octabromoporphyrin. Acta Cryst. 1993, C49, 1339–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kielmann, M.; Senge, M.O. Molecular engineering of free-base porphyrins as ligands—The N−H⋅⋅⋅X binding motif in tetrapyrroles. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 418–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreev, V.P.; Sobolev, P.S.; Zaitsev, D.O.; Tafeenko, V.A. Complex formation between zinc (II) tetraphenylporphyrinate and alkylamines. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2014, 84, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreev, V.P.; Sobolev, P.S.; Zaitsev, D.O.; Remizova, L.A.; Tafeenko, V.A. Coordination of secondary and tertiary amines to zinc tetraphenylporphyrin. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2014, 84, 1979–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osadchuk, I.; Aav, R.; Borovkov, V.; Clot, E. Chirogenesis in zinc porphyrins: Theoretical evaluation of electronic transitions, controlling structural factors, and axial ligation. ChemPhysChem 2021, 22, 1817–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiefl, C.; Sreerama, N.; Haddad, R.; Sun, L.; Jentzen, W.; Lu, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Shelnutt, J.A.; Woody, R.W. Heme distortions in sperm-whale carbonmonoxy myoglobin: Correlations between rotational strengths and heme distortions in MD-generated structures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 3385–3394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Osadchuk, I.; Konrad, N.; Truong, K.-N.; Rissanen, K.; Clot, E.; Aav, R.; Kananovich, D.; Borovkov, V. Supramolecular chirogenesis in bis-porphyrin: Crystallographic structure and cd spectra for a complex with a chiral guanidine derivative. Symmetry 2021, 13, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Thiourea | Vibrio fischeri | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 30-min EC50, mg/L | 95% Confidence Interval | ||

| (R,R)-1a | 7.4 | 6.5 | 7.5 |

| (S,S)-1a | 7.2 | 6.2 | 7.2 |

| (R,R)-1b | >50 b | – | – |

| (R,R)-1c | >50 b | – | – |

| (S,S)-1d | 7.9 | 6.8 | 9.3 |

| ZnSO4 (as Zn2+) | 4.2 | 4.0 | 4.6 |

| Entry | Complex | σpara a | λmax, nm (log ε) | Ka, M−1 (in CH2Cl2 at 293K) b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1a·P1 | – | 433 (5.78), 563 (4.34), 604 (4.07) | (9.0 ± 0.1) × 102 |

| 2 | 1a·P2 | −0.27 | 432 (5.72), 566 (4.21), 610 (4.19) | (2.05 ± 0.01) × 103 |

| 3 | 1a·P3 | 0.00 | 429 (5.77), 563 (4.26), 603 (4.03) c | (2.30 ± 0.04) × 103 |

| 4 | 1a·P4 | 0.06 | 429 (5.63), 562 (4.13), 602 (3.85) | (3.39 ± 0.07) × 103 |

| 5 | 1a·P5 | 0.23 | 430 (5.77), 561 (4.28), 603 (4.00) | (4.18 ± 0.05) × 103 |

| 6 | 1a·P6 | 0.54 | 429 (5.78), 562 (4.31), 602 (3.94) | (2.13 ± 0.02) × 103 |

| 7 | 1a·P7 | 0.66 | 432 (5.65), 564 (4.23), 605 (3.92) | (1.42 ± 0.02) × 103 |

| 8 | 1a·P8 | – | 425 (5.70), 556 (4.35), 602 (3.04) | (1.27 ± 0.02) × 104 |

| 9 | 1a·P9 | – | 470 (5.28), 604 (4.11) | (5.2 ± 0.6) × 105 |

| 10 | 1b·P2 | −0.27 | 432 (5.65), 565 (4.14), 608 (4.06) | (5.8 ± 0.3) × 103 |

| 11 | 1b·P3 | 0.00 | 429 (5.74), 563 (4.23), 603 (3.98) c | (7.640 ± 0.003) × 103 |

| 12 | 1b·P5 | 0.23 | 430 (5.80), 563 (4.32), 603 (4.05) | (9.8 ± 0.1) × 103 |

| 13 | 1b·P6 | 0.54 | 429 (5.08), 563 (4.31), 602 (3.94) | (1.413 ± 0.007) × 104 |

| 14 | 1b·P7 | 0.66 | 432 (5.66), 564 (4.25), 604 (3.93) | (1.91 ± 0.02) × 104 |

| 15 | 1c·P1 | – | 433 (5.76), 564 (4.30), 605 (4.02) | (8.2 ± 0.5) × 103 |

| 16 | 1c·P2 | −0.27 | 432 (5.72), 566 (4.20), 607 (4.13) | (8.35 ± 0.03) × 103 |

| 17 | 1c·P3 | 0.00 | 429 (5.77), 563 (4.26), 603 (4.02) c | (1.116 ± 0.006) × 104 |

| 18 | 1c·P4 | 0.06 | 430 (5.71), 562 (4.20), 603 (3.95) | (1.221 ± 0.005) × 104 |

| 19 | 1c·P5 | 0.23 | 430 (5.78), 564 (4.29), 604 (4.02) | (1.24 ± 0.01) × 104 |

| 20 | 1c·P6 | 0.54 | 429 (5.75), 562 (4.28), 602 (3.89) | (2.16 ± 0.01) × 104 |

| 21 | 1c·P7 | 0.66 | 433 (5.63), 565 (4.21), 605 (3.91) | (2.66 ± 0.03) × 104 |

| 22 | 1c·P8 | – | 425 (5.69), 556 (4.34) | (1.41 ± 0.04) × 105 |

| 23 | 1d·P3 | 0.00 | no strong complex formed | n.d. d |

| 24 | 1d·P8 | – | 425 (5.53), 556 (4.27) | (4.5 ± 0.1) × 102 |

| 25 | 1d·P9 | – | 472 (5.22), 606 (4.10) | (1.16 ± 0.07) × 104 |

| Entry | Complex | CE λmax, nm (Δε, M−1∙cm−1) a |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | (R,R)-1a∙P1 | 439 (+3) |

| 2 | (R,R)-1a∙P2 | 432 (−25) |

| 3 | (R,R)-1a∙P3 | 429 (−25), 436 (+5) b |

| 4 | (R,R)-1a∙P4 | 425 (−7), 432 (+11) |

| 5 | (R,R)-1a∙P5 | 425 (−6), 434 (+12) |

| 6 | (R,R)-1a∙P6 | 426 (−10), 432 (+12) |

| 7 | (R,R)-1a∙P7 | n.d. |

| 8 | (R,R)-1a∙P8 | 426 (+8) |

| 9 | (R,R)-1a∙P9 | 481 (+3) |

| 10 | (R,R)-1b∙P2 | 430 (+10) |

| 11 | (R,R)-1b∙P3 | 429 (+9) b |

| 12 | (R,R)-1b∙P5 | 430 (+23) |

| 13 | (R,R)-1b∙P6 | 429 (+20) |

| 14 | (R,R)-1b∙P7 | 433 (+21) |

| 15 | (R,R)-1c∙P1 | 433 (+12) |

| 16 | (R,R)-1c∙P2 | 435 (+13) |

| 17 | (R,R)-1c∙P3 | 430 (+15) b |

| 18 | (R,R)-1c∙P5 | 431 (+23) |

| 19 | (R,R)-1c∙P6 | 431 (+25) |

| 20 | (R,R)-1c∙P7 | 433 (+22) |

| 21 | (R,R)-1c∙P8 | 426 (+21) |

| 22 | (S,S)-1d∙P8 | 423 (+7) |

| 23 | (S,S)-1d∙P9 | n.d. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Konrad, N.; Horetski, M.; Sihtmäe, M.; Truong, K.-N.; Osadchuk, I.; Burankova, T.; Kielmann, M.; Adamson, J.; Kahru, A.; Rissanen, K.; et al. Thiourea Organocatalysts as Emerging Chiral Pollutants: En Route to Porphyrin-Based (Chir)Optical Sensing. Chemosensors 2021, 9, 278. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors9100278

Konrad N, Horetski M, Sihtmäe M, Truong K-N, Osadchuk I, Burankova T, Kielmann M, Adamson J, Kahru A, Rissanen K, et al. Thiourea Organocatalysts as Emerging Chiral Pollutants: En Route to Porphyrin-Based (Chir)Optical Sensing. Chemosensors. 2021; 9(10):278. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors9100278

Chicago/Turabian StyleKonrad, Nele, Matvey Horetski, Mariliis Sihtmäe, Khai-Nghi Truong, Irina Osadchuk, Tatsiana Burankova, Marc Kielmann, Jasper Adamson, Anne Kahru, Kari Rissanen, and et al. 2021. "Thiourea Organocatalysts as Emerging Chiral Pollutants: En Route to Porphyrin-Based (Chir)Optical Sensing" Chemosensors 9, no. 10: 278. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors9100278

APA StyleKonrad, N., Horetski, M., Sihtmäe, M., Truong, K.-N., Osadchuk, I., Burankova, T., Kielmann, M., Adamson, J., Kahru, A., Rissanen, K., Senge, M. O., Borovkov, V., Aav, R., & Kananovich, D. (2021). Thiourea Organocatalysts as Emerging Chiral Pollutants: En Route to Porphyrin-Based (Chir)Optical Sensing. Chemosensors, 9(10), 278. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors9100278