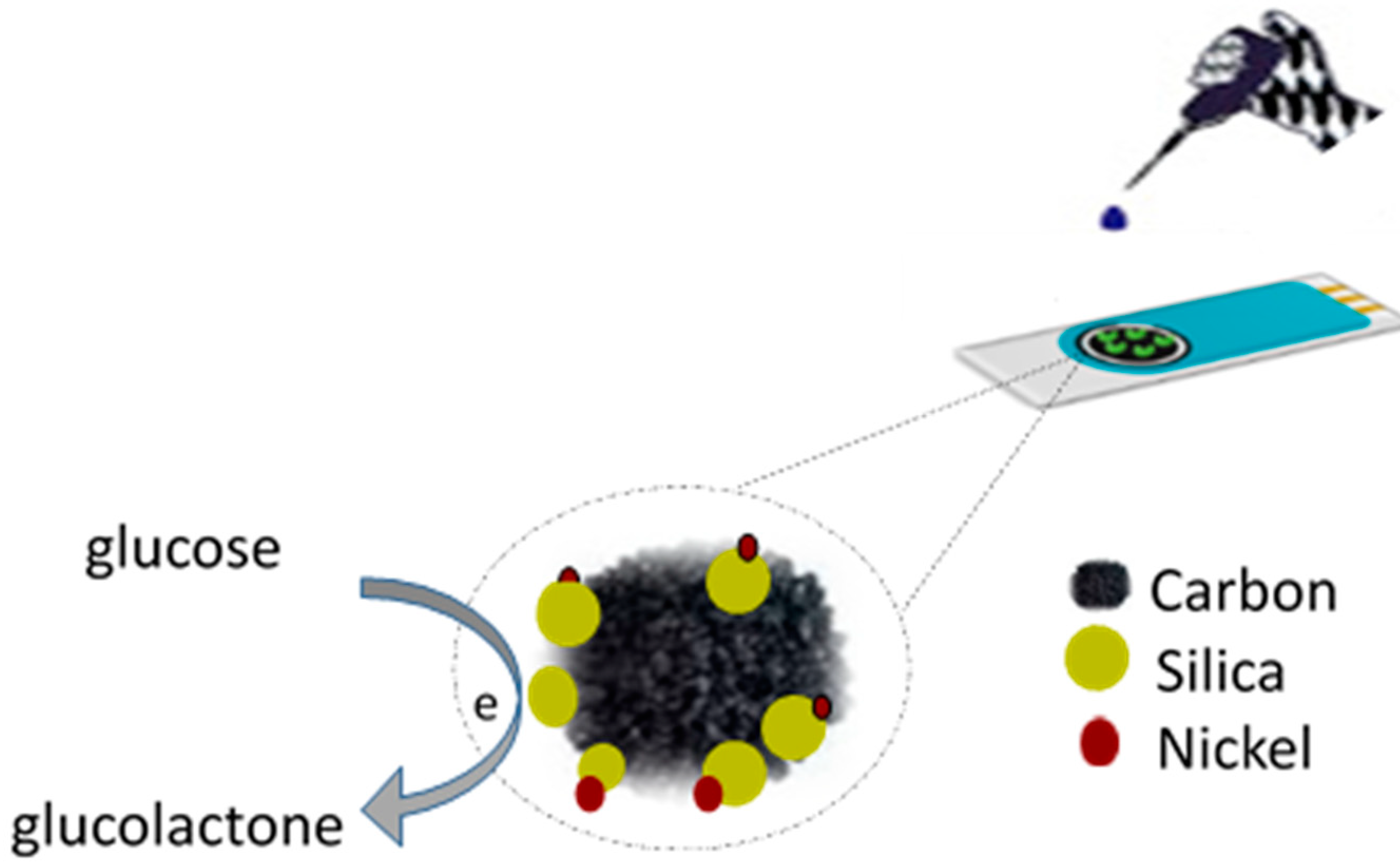

Nanostructured Nickel on Porous Carbon-Silica Matrix as an Efficient Electrocatalytic Material for a Non-Enzymatic Glucose Sensor

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Synthesis of the Porous Carbon Composite

2.2. Characterization and Electrochemical Tests

3. Results and Discussion

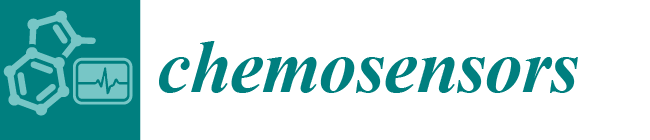

3.1. Characterization of the N-CS Composite

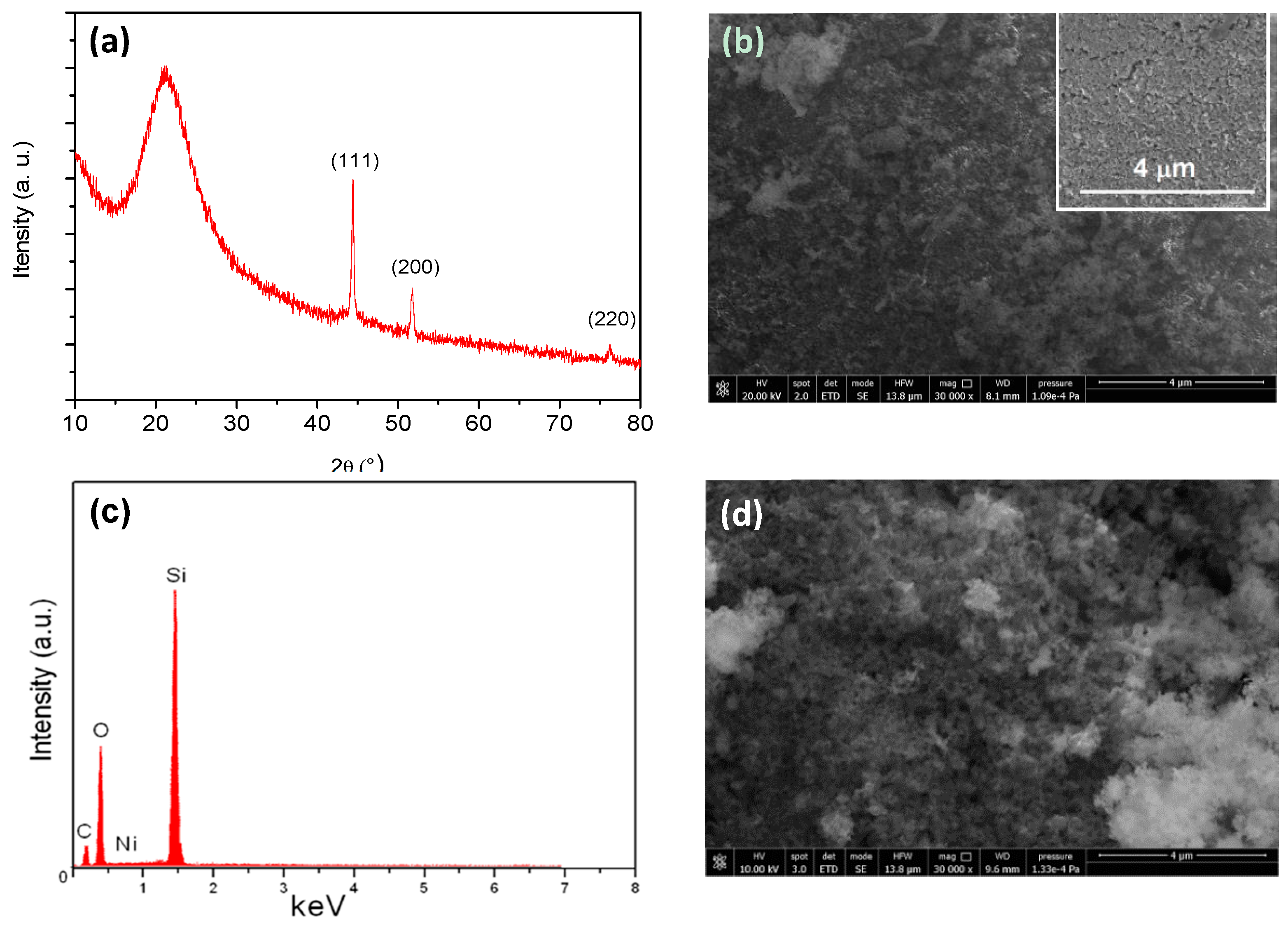

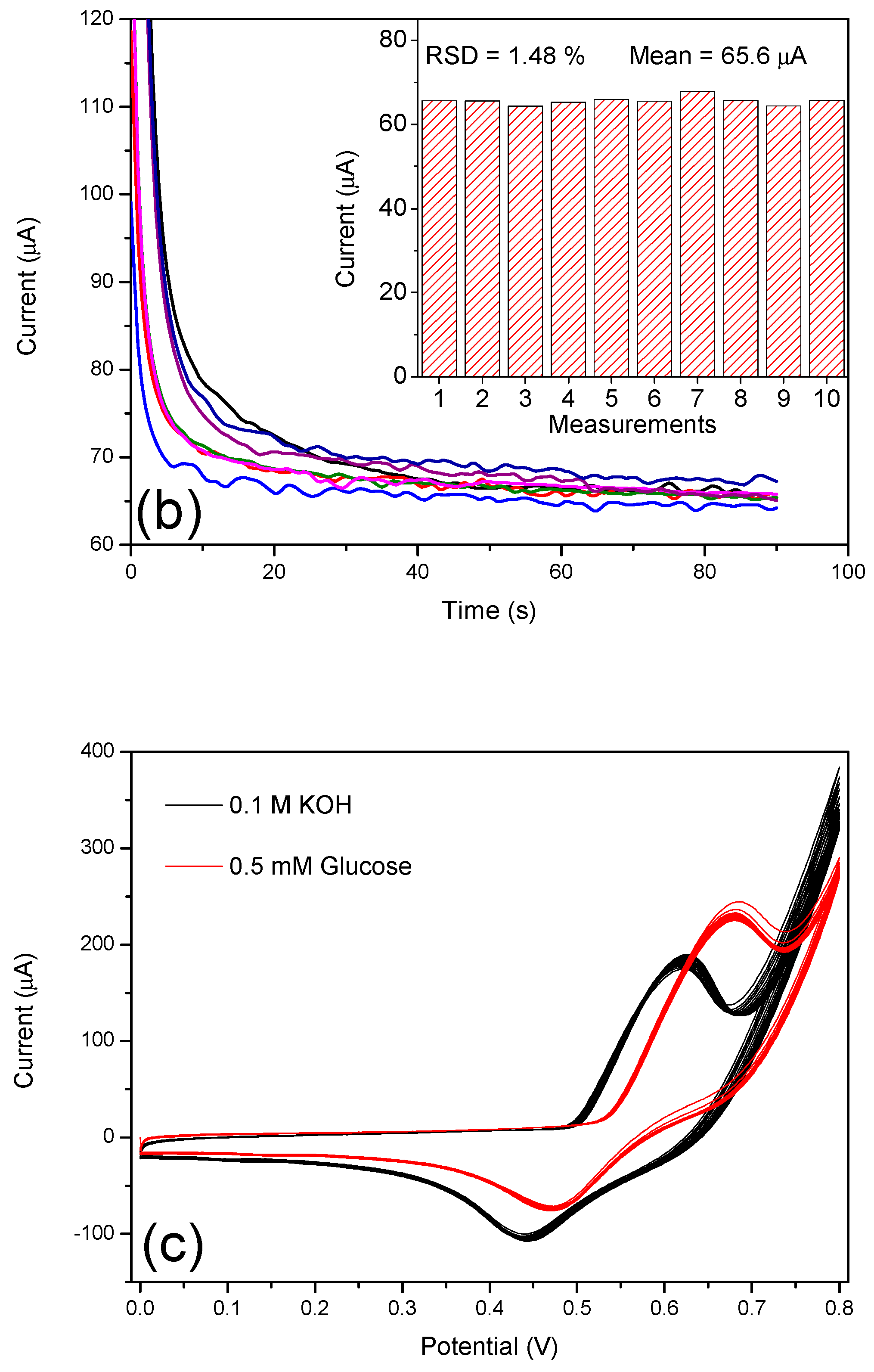

3.2. Cyclic Voltammetry Activation of Ni Nanoparticles

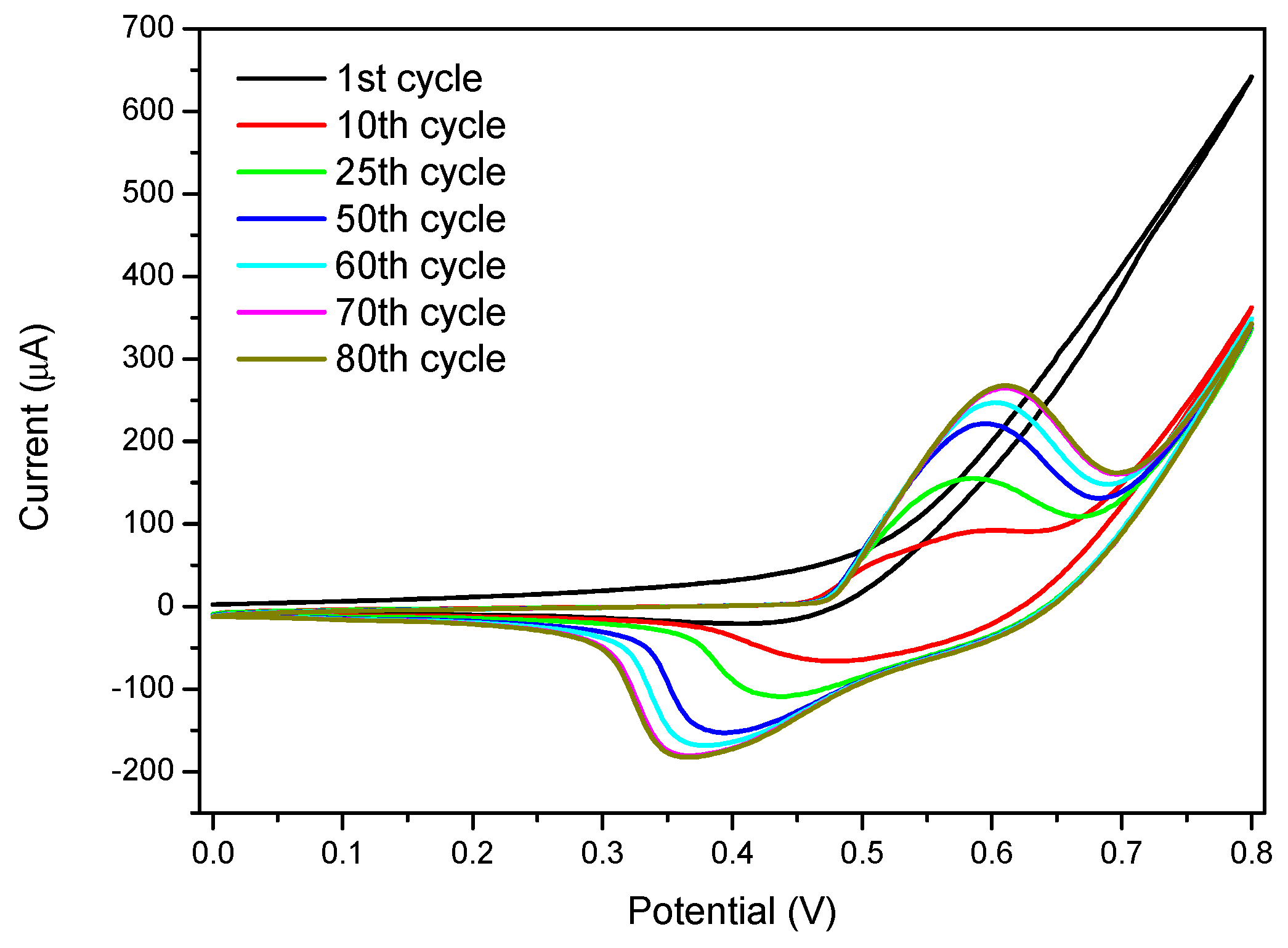

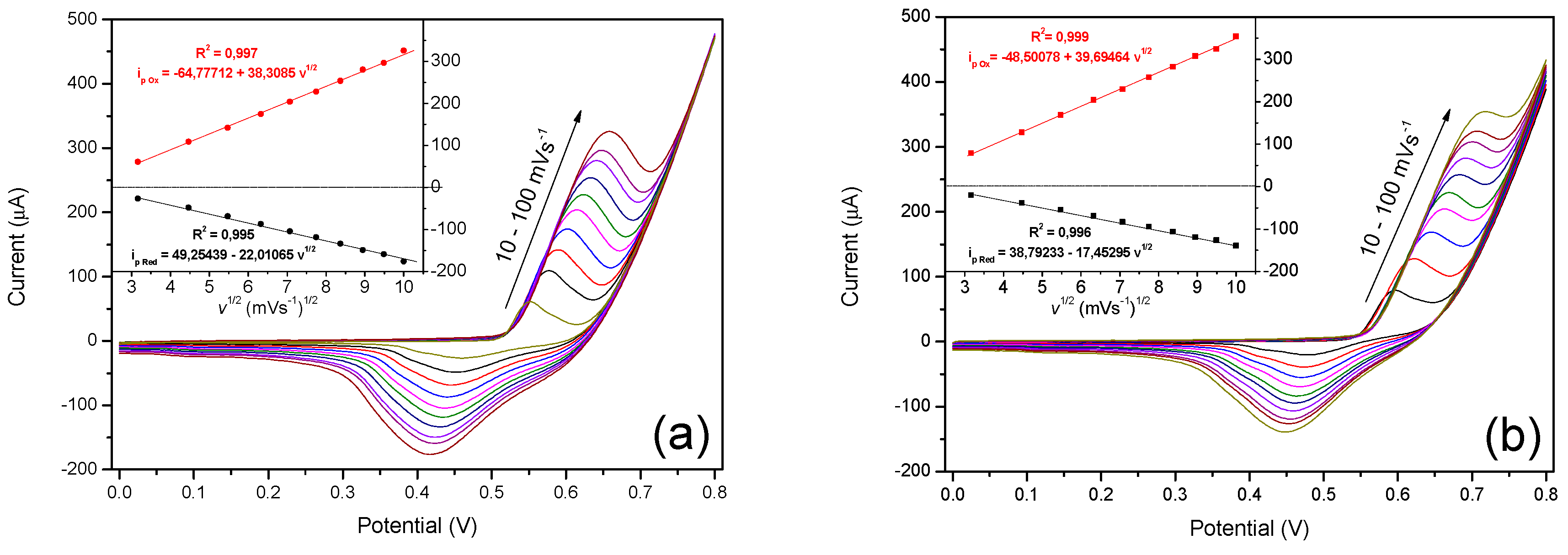

3.3. Electrochemical Oxidation of Glucose on N-CS/SPCE

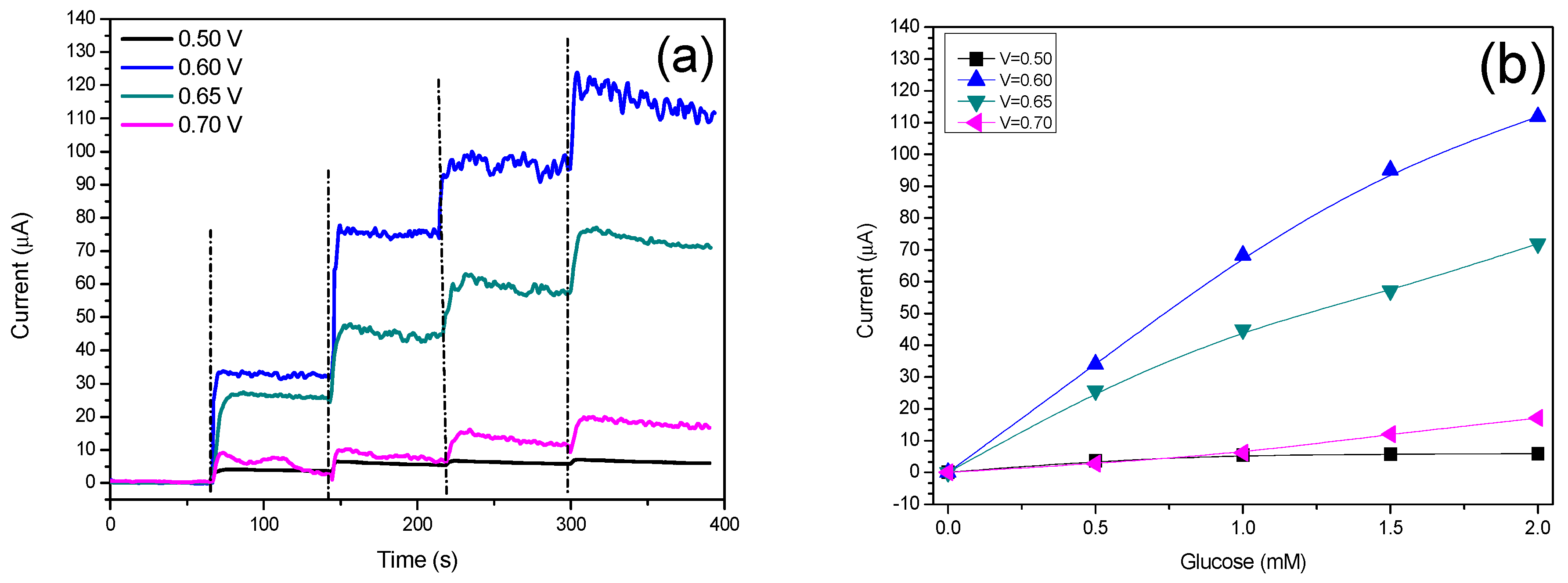

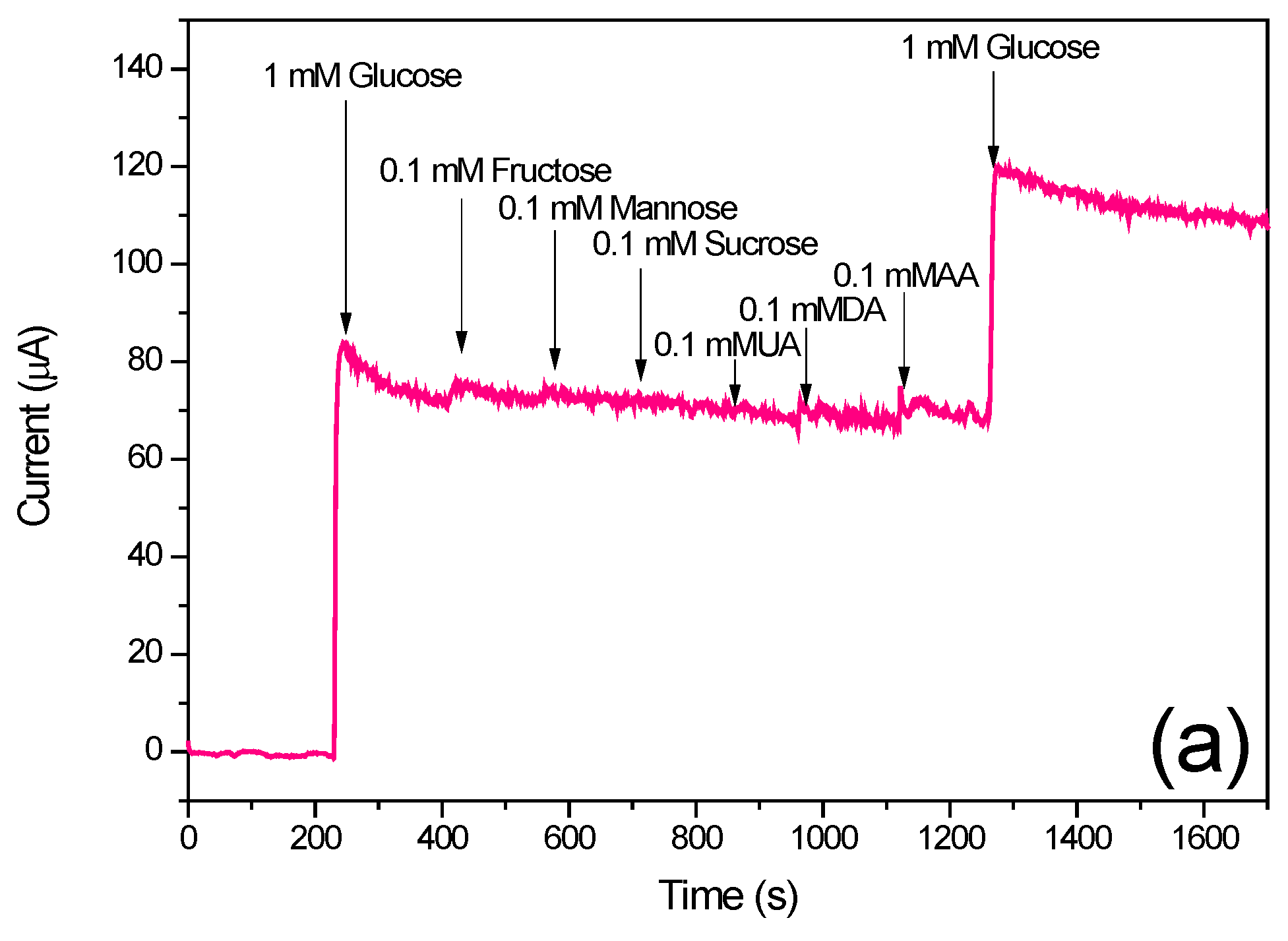

3.4. Amperometric Response of the N-CS/SPCE Towards Glucose

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Z.; Hu, Y.; Yang, W.; Zhou, M.; Hu, X. Facile One-Step Microwave-Assisted Route towards Ni Nanospheres/Reduced Graphene Oxide Hybrids for Non-Enzymatic Glucose Sensing. Sensors 2012, 12, 4860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Xie, Q.; Yang, D.; Xiao, H.; Fu, Y.; Tan, Y.; Yao, S. Recent advances in electrochemical glucose biosensors: A review. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 4473–4491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Su, L.; Manuzzi, D.; de los Monteros, H.V.E.; Jia, W.; Huo, D.; Hou, C.; Lei, Y. Ultrasensitive and selective non-enzymatic glucose detection using copper nanowires. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2012, 31, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.X.; Zheng, X.T.; Lu, Z.S.; Lou, X.W.; Li, C.M. Biointerface by Cell Growth on Layered Graphene–Artificial Peroxidase–Protein Nanostructure for In Situ Quantitative Molecular Detection. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 5164–5167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, Y.; Yan, X.; Zhao, J.; Liu, X.; Song, Y.; Luo, N.; Zhang, Y. Improved glucose electrochemical biosensor by appropriate immobilization of nano-ZnO. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces 2011, 82, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Liao, Q.; Liu, S.; Kang, Z.; Zhang, Y. Nonenzymatic Glucose Sensor Based on In Situ Reduction of Ni/NiO-Graphene Nanocomposite. Sensors 2016, 16, 1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espro, C.; Donato, N.; Galvagno, S.; Aloisio, D.; Leonardi, S.G.; Neri, G. CuO nanowires-based electrodes for glucose sensors. Chem. Eng. 2014, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Lu, Y.; Liu, M.; He, S.; Chen, W. Sub-nanometer sized Cu6(GSH)3 clusters: One-step synthesis and electrochemical detection of glucose. J. Mater. Chem. C 2015, 3, 4050–4056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, S.G.; Marini, S.; Espro, C.; Bonavita, A.; Galvagno, S.; Neri, G. In-situ grown flower-likenanostructured CuO on screen printed carbon electrodes for non-enzymatic amperometric sensing of glucose. Microchim. Acta 2017, 184, 2375–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Wen, Z.; Li, Z. Graphene–Pt nanocomposite for nonenzymatic detection of hydrogen peroxide with enhanced sensitivity. Electrochem. Commun. 2011, 13, 1131–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.-M.; Li, H.-B.; Qu, F.; Zhang, X.-B.; Shen, G.-L.; Yu, R.-Q. In situ synthesis of palladium nanoparticle–graphene nanohybrids and their application in nonenzymatic glucose biosensors. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2011, 26, 3500–3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, J.; Liu, X. A novel non-enzymatic glucose sensor based on Cu nanoparticle modified graphene sheets electrode. Anal. Chim. Acta 2012, 709, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Jiang, J.; Liu, J.; Ding, R.; Li, Y.; Ding, H.; Feng, Y.; Wei, G.; Huang, X. CNT-network modified Ni nanostructured arrays for high performance non-enzymatic glucose sensors. RSC Adv. 2011, 1, 1020–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; Jia, D.; He, Y.; Miao, Y.; Wu, H.-L. Nano nickel oxide modified non-enzymatic glucose sensors with enhanced sensitivity through an electrochemical process strategy at high potential. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2011, 26, 2948–2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.-M.; Zhang, L.; Qu, F.-L.; Lu, H.-X.; Zhang, X.-B.; Wu, Z.-S.; Huan, S.-Y.; Wang, Q.-A.; Shen, G.-L.; Yu, R.-Q. A nano-Ni based ultrasensitive nonenzymatic electrochemical sensor for glucose: Enhancing sensitivity through a nanowire array strategy. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2009, 25, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ci, S.; Huang, T.; Wen, Z.; Cui, S.; Mao, S.; Steeber, D.A.; Chen, J. Nickel oxide hollow microsphere for non-enzyme glucose detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2014, 54, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, F.; Sun, Y.; Shi, Y.; Wen, Z.; Li, Z. Assembly of Ni(OH)2 nanoplates on reduced graphene oxide: A two dimensional nanocomposite for enzyme-free glucose sensing. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 16949–16954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; He, X.; Wang, L.; Gu, A.; Huang, Y.; Fang, B.; Geng, B.; Zhang, X. Non-Enzymatic Electrochemical Sensing of Glucose. Microchim. Acta 2013, 180, 161–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Liu, D.; Zhang, X.; Li, L.; Hou, H.; Niwa, O.; You, T. Pd–Ni Alloy Nanoparticle/Carbon Nanofiber Composites: Preparation, Structure, and Superior Electrocatalytic Properties for Sugar Analysis. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 5898–5905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.; Peng, X.; Cao, G.; Zhou, M.; Qiao, L.; Yao, J.; He, H. Ni nanoparticles decorated titania nanotube arrays as efficient nonenzymatic glucose sensor. Electrochim. Acta 2012, 76, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Teng, H.; Hou, H.; You, T. Nonenzymatic glucose sensor based on renewable electrospun Ni nanoparticle-loaded carbon nanofiber paste electrode. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2009, 24, 3329–3334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Yu, J.-H.; Rudi Strickler, J.; Chang, W.-J.; Gunasekaran, S. Nickel nanoparticle–chitosan-reduced graphene oxide-modified screen-printed electrodes for enzyme-free glucose sensing in portable microfluidic devices. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2013, 47, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Li, F.; Zhao, C.; Qian, X. One-step construction of hierarchical Ni(OH)2/RGO/Cu2O on Cu foil for ultra- sensitive non-enzymatic glucose and hydrogen peroxide detection. Sens. Actuators B 2018, 274, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, M.; Konno, H.; Tanaike, O. Carbon materials for electrochemical capacitors. J. Power Sources 2010, 195, 7880–7903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Dou, Y.; Zhao, D.; Fulvio, P.F.; Mayes, R.T.; Dai, S. Carbon materials for chemical capacitive energy storage. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 4828–4850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Zhu, S.; Luque, R.; Han, S.; Hu, L.; Xu, G. Recent development of carbon electrode materials and their bioanalytical and environmental applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 715–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marini, S.; Ben Mansour, N.; Hjiri, M.; Dhahri, R.; El Mir, L.; Espro, C.; Bonavita, A.; Galvagno, S.; Neri, G.; Leonardi, S.G. Non-enzymatic Glucose Sensor Based on Nickel/Carbon Composite. Electroanalysis 2018, 30, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Hao, P.; Sun, W.; Shi, R.; Liu, S. Ordered mesoporous silica-carbon-supported copper catalyst as an efficient and stable catalyst for catalytic oxidative carbonylation. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 328, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhao, Q.; Klingstedt, M.; Terasaki, O.; Zhao, D. Ordered Mesoporous Pd/Silica−Carbon as a Highly Active Heterogeneous Catalyst for Coupling Reaction of Chlorobenzene in Aqueous Media. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 4541–4550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ru, Y.; Evans, D.G.; Zhu, H.; Yang, W. Facile fabrication of yolk–shell structured porous Si–C microspheres as effective anode materials for Li-ion batteries. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pissinis, D.E.; Sereno, L.n.E.; Marioli, J.M. Utilization of Special Potential Scan Programs for Cyclic Voltammetric Development of Different Nickel Oxide-Hydroxide Species on Ni Based Electrodes. Open J. Phys. Chem. 2012, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuković, M. Voltammetry and anodic stability of a hydrous oxide film on a nickel electrode in alkaline solution. J. Appl. Electrochem. 1994, 24, 878–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seghiouer, A.; Chevalet, J.; Barhoun, A.; Lantelme, F. Electrochemical oxidation of nickel in alkaline solutions: A voltammetric study and modelling. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1998, 442, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medway, S.L.; Lucas, C.A.; Kowal, A.; Nichols, R.J.; Johnson, D. In situ studies of the oxidation of nickel electrodes in alkaline solution. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2006, 587, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marioli, J.M.; Sereno, L.E. Electrochemical Detection of Underivatized Amino Acids with a Ni-Cr Alloy Electrode. J. Liquid Chromatogr. Related Technol. 1996, 19, 2505–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, H.; Dehmelt, K.; Witte, J. Zur kenntnis der nickelhydroxidelektrode—I. Über das nickel (II)-hydroxidhydrat. Electrochim. Acta 1966, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiao, X.; Sun, Y.; Shi, Y.; Dai, H.; Ni, P.; Hu, J.; Li, Z.; Song, Y.; Wang, L. Electrochemical Deposition of Nickel Nanoparticles on Reduced Graphene Oxide Film for Nonenzymatic Glucose Sensing. Electroanalysis 2013, 25, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toghill, K.E.; Compton, R.G. Electrochemical non-enzymatic glucose sensors: A perspective and an evaluation. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci 2010, 5, 1246–1301. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Omair, M.A.; Touny, A.H.; Al-Odail, F.A.; Saleh, M.M. Electrocatalytic Oxidation of Glucose at Nickel Phosphate Nano/Micro Particles Modified Electrode. Electrocatalysis 2017, 8, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lu, X.; Wen, C.; Xie, Y.; Miao, L.; Chen, S.; Li, H.; Li, P.; Song, Y. One-step synthesis of Pt–NiO nanoplate array/reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites for nonenzymatic glucose sensing. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Electrode | Sensitivity (µA·mM−1·cm−2) | Linear Range (mM) | Detection Limit (µM) | Applied Voltage (V) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N-CS | 585 | 0.05–1.5 | 30 | 0.6 | This work |

| Ni/NiO-rGO | 1997 | -- | 1.8 | 0.55 | [6] |

| PF/Ni30 | 670 | 0.05–0.5 | 8 | 0.6 | [27] |

| Ni nanoparticles/CF | 420.4 | 0.002–2.5 | 1 | 0.6 | [21] |

| Ni(OH)2 nanosheet | 0.65 (µA·mM−1) | 0.25–39.26 | 23 | 0.55 | [1] |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zahmouli, N.; Marini, S.; Guediri, M.; Ben Mansour, N.; Hjiri, M.; El Mir, L.; Espro, C.; Neri, G.; Leonardi, S.G. Nanostructured Nickel on Porous Carbon-Silica Matrix as an Efficient Electrocatalytic Material for a Non-Enzymatic Glucose Sensor. Chemosensors 2018, 6, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors6040054

Zahmouli N, Marini S, Guediri M, Ben Mansour N, Hjiri M, El Mir L, Espro C, Neri G, Leonardi SG. Nanostructured Nickel on Porous Carbon-Silica Matrix as an Efficient Electrocatalytic Material for a Non-Enzymatic Glucose Sensor. Chemosensors. 2018; 6(4):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors6040054

Chicago/Turabian StyleZahmouli, Nassim, Silvia Marini, Mouna Guediri, Nabil Ben Mansour, Mokhtar Hjiri, Lassaad El Mir, Claudia Espro, Giovanni Neri, and Salvatore Gianluca Leonardi. 2018. "Nanostructured Nickel on Porous Carbon-Silica Matrix as an Efficient Electrocatalytic Material for a Non-Enzymatic Glucose Sensor" Chemosensors 6, no. 4: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors6040054

APA StyleZahmouli, N., Marini, S., Guediri, M., Ben Mansour, N., Hjiri, M., El Mir, L., Espro, C., Neri, G., & Leonardi, S. G. (2018). Nanostructured Nickel on Porous Carbon-Silica Matrix as an Efficient Electrocatalytic Material for a Non-Enzymatic Glucose Sensor. Chemosensors, 6(4), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors6040054