Silver Nanowires with Efficient Peroxidase-Emulating Activity for Colorimetric Detection of Hydroquinone in Various Matrices

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Chemicals, Reagents, and Materials

2.2. Instrumentation

2.3. Synthesis of Silver Nanowires

2.4. Analytical Procedures for the Determination of Hydroquinone

2.5. Application to Water Samples

2.6. Determination of HQN in Pharmaceutical Cream

3. Results and Discussion

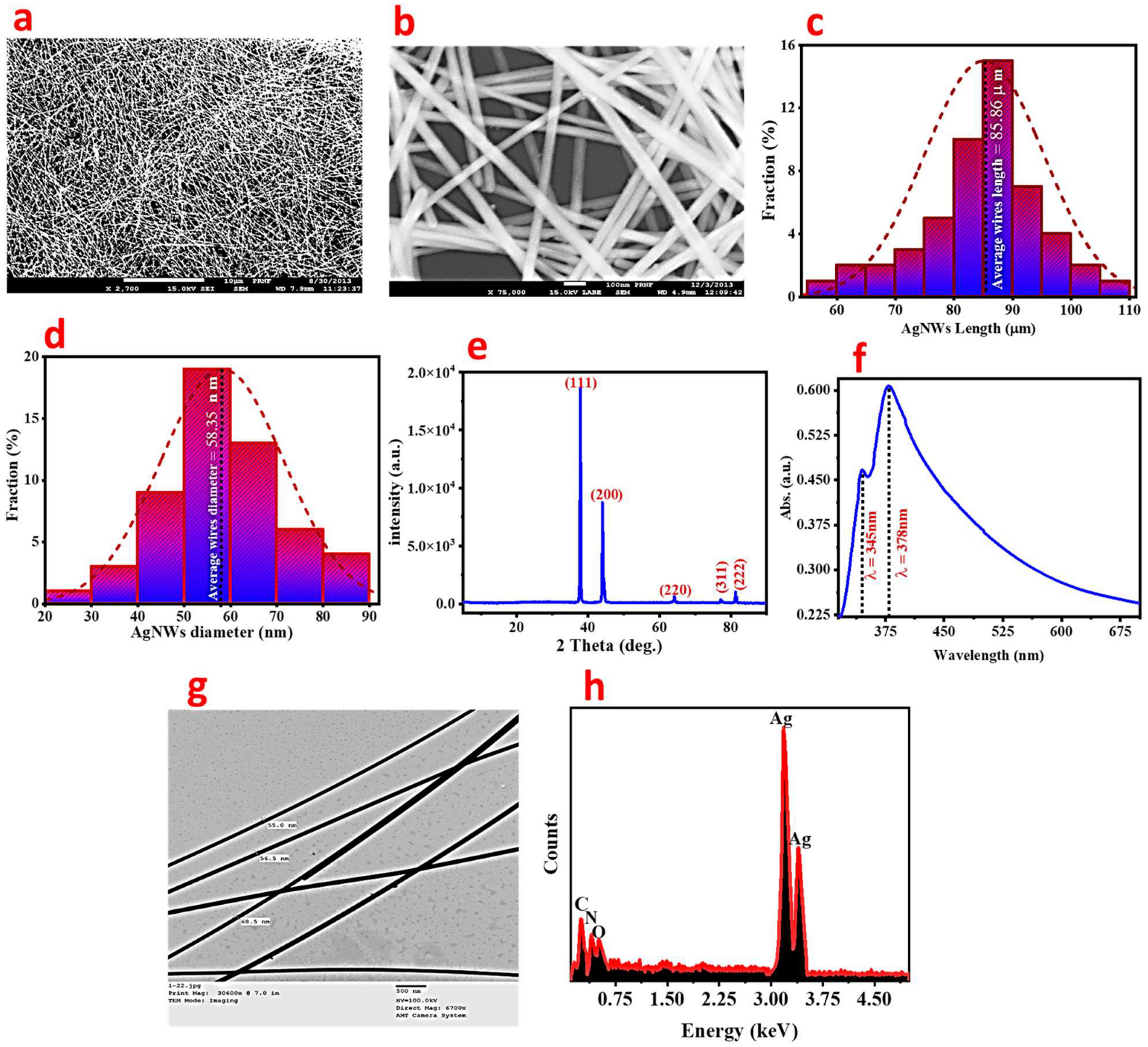

3.1. Characterization of Ag-NWs

3.1.1. SEM Analysis

3.1.2. XRD Analysis

3.1.3. UV-Spectroscopy Analysis

3.1.4. TEM Analysis

3.1.5. EDX Spectroscopy

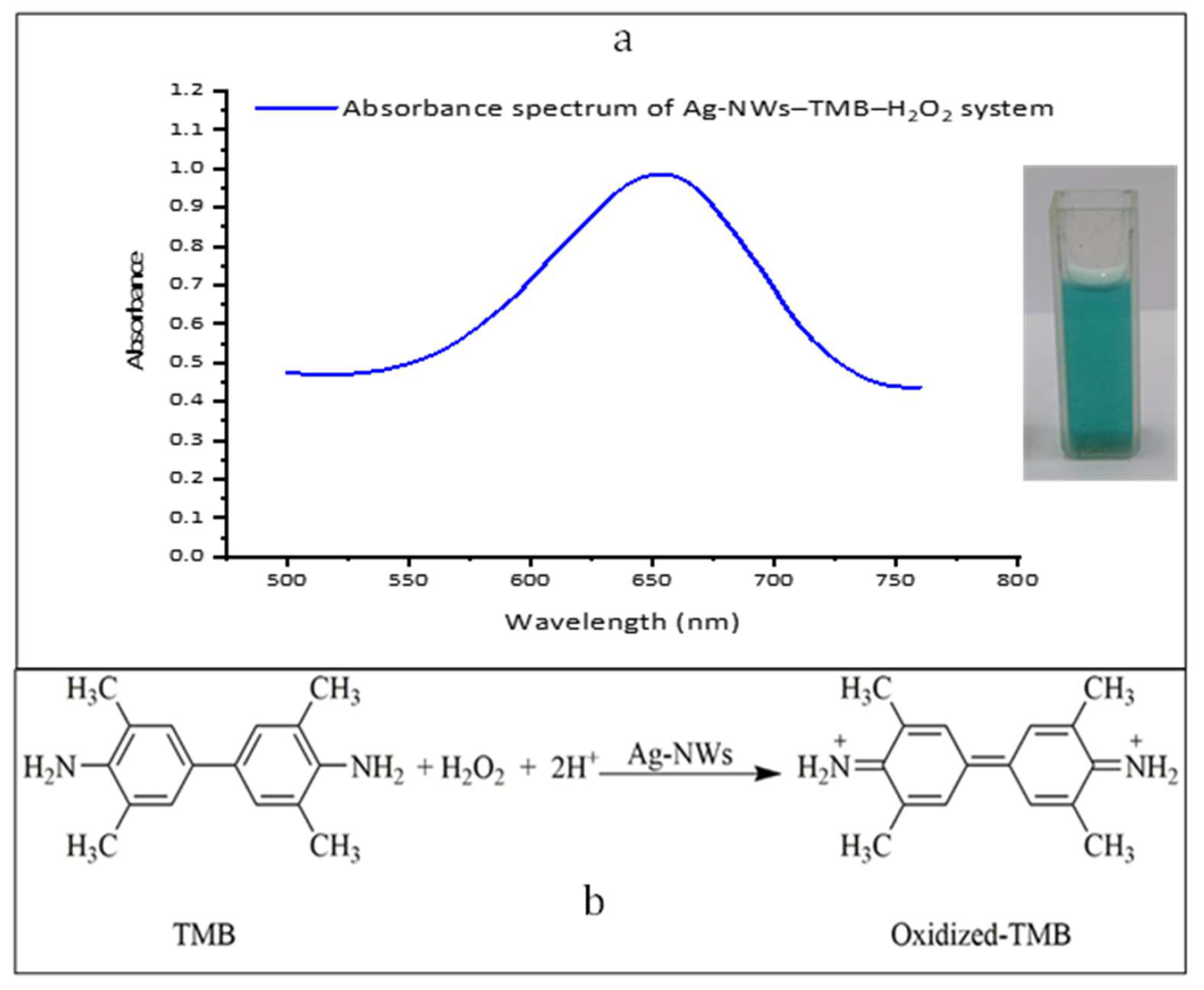

3.2. Peroxidase-Emulating Activity of the Prepared Ag-NWs

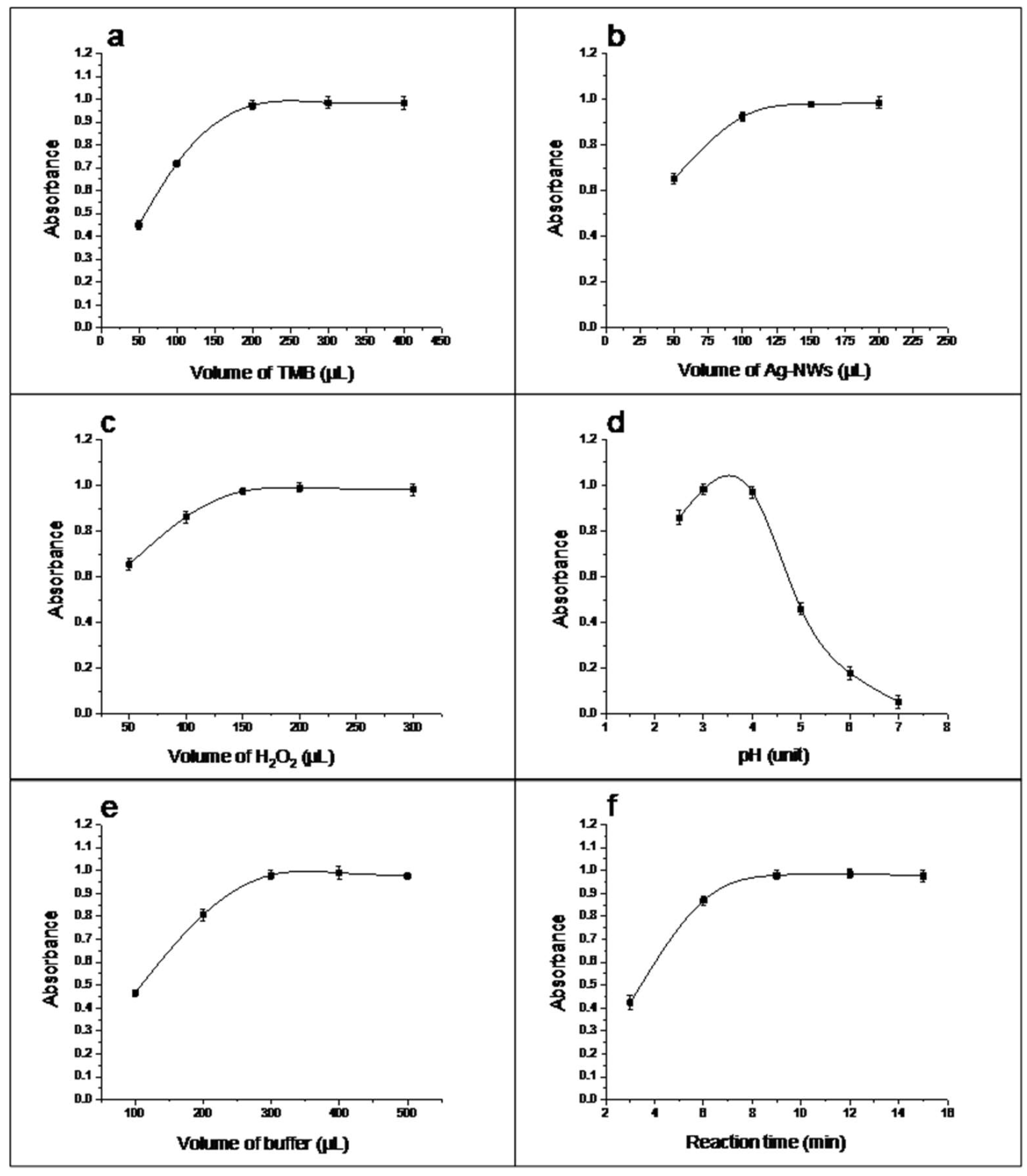

3.3. Optimization of the Catalytic Conditions

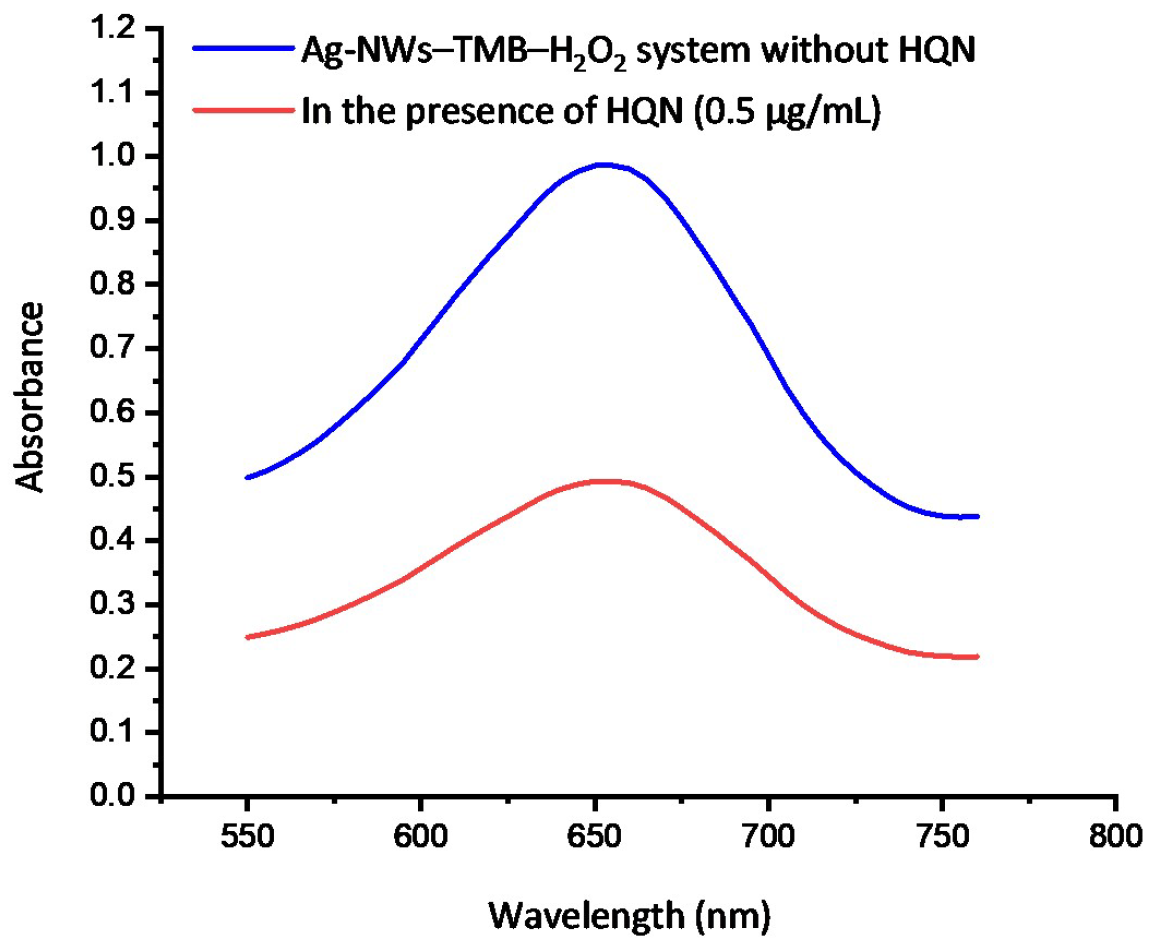

3.4. Principle of the Detection and Method Validation

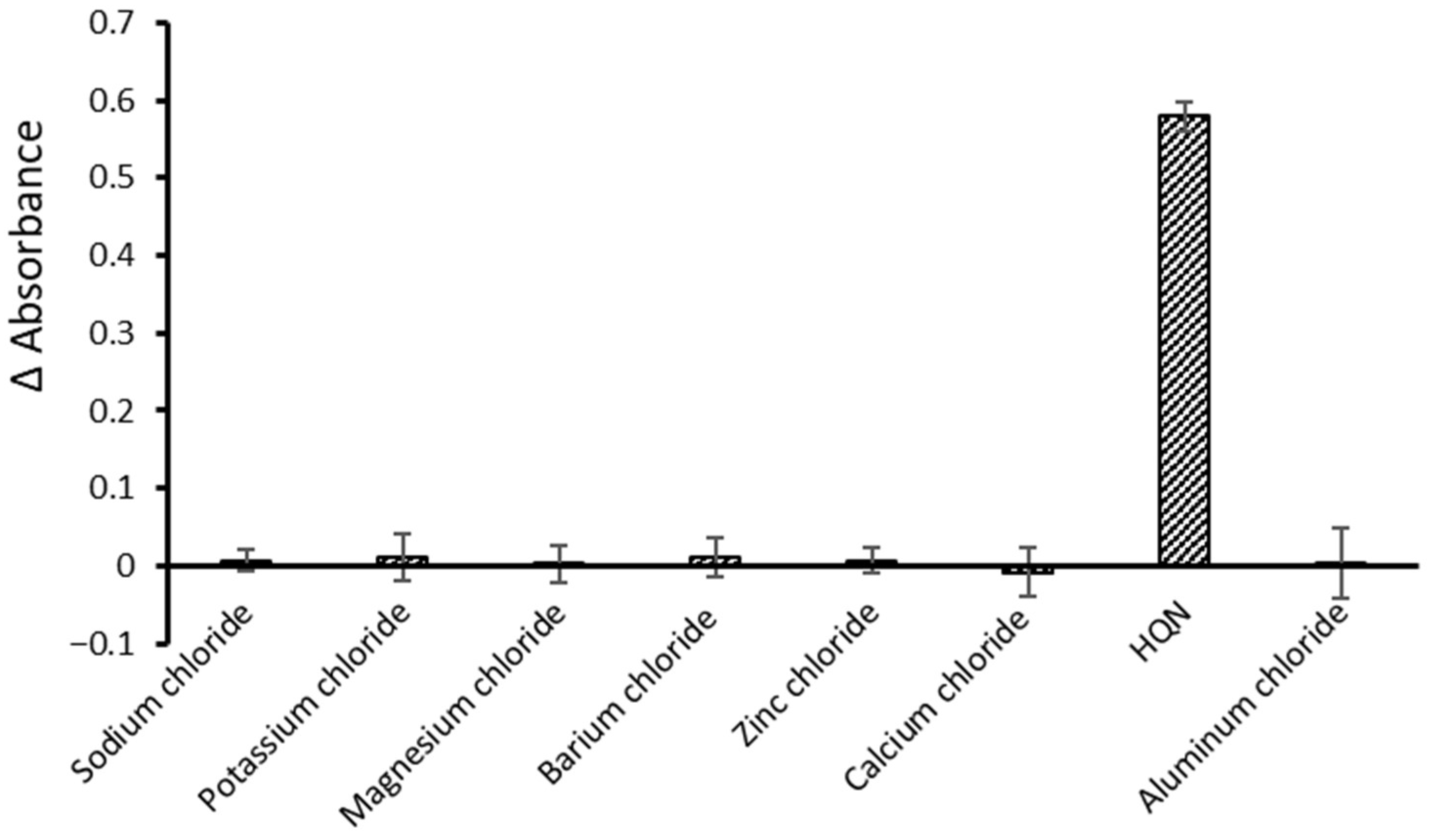

3.5. Selectivity Study

3.6. Application to Water and Pharmaceutical Samples

3.7. Advantages of Ag-NWs as a Hydroquinone Detector

3.8. Limitations

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pu, H.; Sun, Q.; Tang, P.; Zhao, L.; Li, Q.; Liu, Y.; Li, H. Characterization and antioxidant activity of the complexes of tertiary butylhydroquinone with β-cyclodextrin and its derivatives. Food Chem. 2018, 260, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cheng, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Tammina, S.K.; Yang, Y. A double carbon dot system composed of N, Cl-doped carbon dots and N, Cu-doped carbon dots as peroxidase mimics and as fluorescent probes for the determination of hydroquinone by fluorescence. Microchim. Acta 2020, 187, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Guo, S.; Jia, P.; Shui, Y.; Yao, S.; Huang, C.; Zhang, M.; Wang, L. Highly selective and sensitive fluorescence detection of hydroquinone using novel silicon quantum dots. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 275, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Wang, X.; Meng, X.; Zheng, H.; Suye, S.-i. Amperometric determination of hydroquinone and catechol on gold electrode modified by direct electrodeposition of poly (3, 4-ethylenedioxythiophene). Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2014, 193, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, V.M.; Pandya, A.G. Melasma: A comprehensive update: Part II. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2011, 65, 699–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqarni, M.H.; Alam, P.; Shakeel, F.; Foudah, A.I.; Alshehri, S. Highly sensitive and ecologically sustainable reversed-phase hptlc method for the determination of hydroquinone in commercial whitening creams. Processes 2021, 9, 1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachmin, I.; Ostrowski, S.M.; Weng, Q.Y.; Fisher, D.E. Topical treatment strategies to manipulate human skin pigmentation. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2020, 153, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordin, F.N.; Aziz, A.; Zakaria, Z.; Wan Mohamed Radzi, C.W.J. A systematic review on the skin whitening products and their ingredients for safety, health risk, and the halal status. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2021, 20, 1050–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MC, S.; Becker Jr, S. A hydroquinone effect. Clin. Med. 1963, 70, 1111–1114. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M.; Jones, T.W.; Monks, T.J.; Lau, S.S. Cytotoxicity and cell-proliferation induced by the nephrocarcinogen hydroquinone and its nephrotoxic metabolite 2, 3, 5-(tris-glutathion-S-yl) hydroquinone. Carcinogenesis 1997, 18, 2393–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Katsambas, A.; Antoniou, C. Melasma. Classification and treatment. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 1995, 4, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, M.; Metwalli, M. Topical hydroquinone in the treatment of some hyperpigmentary disorders. Int. J. Dermatol. 1998, 37, 449–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, N.; Yang, L.; Wang, L.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Sun, X.; Zhao, M.; Tan, W.; Yang, J. Cu/Mn synergy catalysis-based colorimetric sensor for visual detection of hydroquinone. Coatings 2024, 14, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Shi, Z.; Chen, M.; Xi, F. Highly active nanozyme based on nitrogen-doped graphene quantum dots and iron ion nanocomposite for selective colorimetric detection of hydroquinone. Talanta 2025, 281, 126817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, D.; Wang, Y.; Wen, S.; Kang, Y.; Cui, X.; Tang, R.; Yang, X. Metal-organic framework composite Mn/Fe-MOF@ Pd with peroxidase-like activities for sensitive colorimetric detection of hydroquinone. Anal. Chim. Acta 2023, 1279, 341797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wang, Z.; Wei, T.; Liu, Z.; Li, J. Bimetallic FeMn-N nanoparticles as nanocatalyst with dual enzyme-mimic activities for simultaneous colorimetric detection and degradation of hydroquinone. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 110186. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, N.; Ge, X.; Zhao, Y.; Xia, L.; Song, Z.-L.; Kong, R.-M.; Qu, F. Promoting sensitive colorimetric detection of hydroquinone and Hg2+ via ZIF-8 dispersion enhanced oxidase-mimicking activity of MnO2 nanozyme. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 454, 131455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Xue, Y.; Hou, S.; Song, P.; Wu, T.; Zhao, H.; Osman, N.A.; Alanazi, A.K.; Gao, Y.; Abo-Dief, H.M. Highly selective colorimetric platinum nanoparticle-modified core-shell molybdenum disulfide/silica platform for selectively detecting hydroquinone. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2023, 6, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, B.; Li, J.; Liu, Z. Water-induced CsPbBr3@ PbBr (OH) semiconductor for highly sensitive colorimetric detection of hydroquinone. Mater. Lett. 2023, 338, 134014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, B.; Wei, T.; Liu, Z.; Li, J. Self-propelled Janus magnetic micromotors as peroxidase-like nanozyme for colorimetric detection and removal of hydroquinone. Environ. Sci. Nano 2023, 10, 476–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Liu, K.; Ji, X.; Cui, Y.; Li, R.; Ma, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L. Biocompatible palladium nanoparticles prepared using vancomycin for colorimetric detection of hydroquinone. Polymers 2023, 15, 3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Feng, M.; Zhang, X.; Huang, Y. Metal-organic framework (MOF)-derived flower-like Ni-MOF@ NiV-layered double hydroxides as peroxidase mimetics for colorimetric detection of hydroquinone. Anal. Chim. Acta 2023, 1283, 341959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaka, M.N.; Borah, N.; Baruah, D.; Phukan, A.; Tamuly, C. Ag-nanozyme as peroxidase mimetic for colorimetric detection of dihydroxybenzene isomers and hydroquinone estimation in real samples. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2024, 166, 112580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, J.; Pang, H.; Khan, S.U.; Wu, Q.; Jin, Z.; Yu, X.; Ma, H.; Wang, X.; Yang, G.; Tan, L. Polyoxometalate-based metal–organic frameworks directed fabrication of defective-1 T/2H-MoS2/ZnS heterostructured nanozyme for colorimetric determination of hydroquinone. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 619, 156713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzinger, M.; Le Goff, A.; Cosnier, S. Nanomaterials for biosensing applications: A review. Front. Chem. 2014, 2, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Lateef, M.A. Utilization of the peroxidase-like activity of silver nanoparticles nanozyme on O-phenylenediamine/H2O2 system for fluorescence detection of mercury (II) ions. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Onazi, W.A.; Abdel-Lateef, M.A. Catalytic oxidation of O-phenylenediamine by silver nanoparticles for resonance Rayleigh scattering detection of mercury (II) in water samples. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2022, 264, 120258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlSalem, H.S.; Binkadem, M.S.; Al-Goul, S.T.; Abdel-Lateef, M.A. Synthesis of green emitted carbon dots from Vachellia nilotica and utilizing its extract as a red emitted fluorescence reagent: Applying for visual and spectroscopic detection of iron (III). Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2023, 295, 122616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Lateef, M.A.; Alzahrani, E.; Pashameah, R.A.; Almahri, A.; Abu-Hassan, A.A.; El Hamd, M.A.; Mohammad, B.S. A specific turn-on fluorescence probe for determination of nitazoxanide based on feasible oxidation reaction with hypochlorite: Applying cobalt ferrite nanoparticles for pre-concentration and extraction of its metabolite from real urine samples. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2022, 219, 114941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Z.X.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Lu, J.Y.; Huang, W.T. Multifunctional Antimonene-Silver Nanocomposites for Ultra-Multi-Mode and Multi-Analyte Sensing, Parallel and Batch Logic Computing, Long-Text Information Protection. Small 2024, 20, 2401510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Long, Z.; Li, Y.; Qiu, H. Colorimetric Detection of Acid Phosphatase and Malathion Using NiCo2O4 Nanosheets as Peroxidase-Mimicking Activity. J. Anal. Test. 2024, 8, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatsyayan, P.; Iffelsberger, C.; Mayorga-Martinez, C.C.; Matysik, F.-M. Imaging of localized enzymatic peroxidase activity over unbiased individual gold nanowires by scanning electrochemical microscopy. Anal. Methods 2016, 8, 6847–6855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-Y.; Rheima, A.M.; sabri Abbas, Z.; Faryad, M.U.; Kadhim, M.M.; Altimari, U.S.; Dawood, A.H.; Abed, Z.T.; Radhi, R.S.; Jaber, A.S. Nanowires properties and applications: A review study. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2023, 46, 286–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kumar, M.; Goyat, M.; Avasthi, D. A review of the latest developments in the production and applications of Ag-nanowires as transparent electrodes. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 33, 104433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wong, S.S. Ultrathin metallic nanowire-based architectures as high-performing electrocatalysts. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 3294–3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvo-Comino, C.; Martin-Pedrosa, F.; Garcia-Cabezon, C.; Rodriguez-Mendez, M.L. Silver nanowires as electron transfer mediators in electrochemical catechol biosensors. Sensors 2021, 21, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Jiang, L.; He, Y.; Liu, J.; Cao, K.; Wang, J.; He, Y.; Ni, H.; Chi, H.; Ji, Z. Carbon supported silver nanowires with enhanced catalytic activity and stability used as a cathode in a direct borohydride fuel cell. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 15323–15328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenigsmann, C.; Wong, S.S. One-dimensional noble metal electrocatalysts: A promising structural paradigm for direct methanol fuel cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 1161–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfenden, R.; Snider, M.J. The depth of chemical time and the power of enzymes as catalysts. Acc. Chem. Res. 2001, 34, 938–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Viloca, M.; Gao, J.; Karplus, M.; Truhlar, D.G. How enzymes work: Analysis by modern rate theory and computer simulations. Science 2004, 303, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. Catalytically active nanomaterials: A promising candidate for artificial enzymes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Zheng, H.; Huang, Y.; Xie, J. Analytical and environmental applications of nanoparticles as enzyme mimetics. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2012, 39, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, Y.; Kikuchi, J.-i.; Hisaeda, Y.; Hayashida, O. Artificial enzymes. Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 721–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breslow, R. Biomimetic chemistry and artificial enzymes: Catalysis by design. Acc. Chem. Res. 1995, 28, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotov, N.A. Inorganic nanoparticles as protein mimics. Science 2010, 330, 188–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotelnikova, P.A.; Iureva, A.M.; Nikitin, M.P.; Zvyagin, A.V.; Deyev, S.M.; Shipunova, V.O. Peroxidase-like activity of silver nanowires and its application for colorimetric detection of the antibiotic chloramphenicol. Talanta Open 2022, 6, 100164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Rahim, R.D.; Emran, M.Y.; Nagiub, A.M.; Farghaly, O.A.; Taher, M.A. Silver nanowire size-dependent effect on the catalytic activity and potential sensing of H2O2. Electrochem. Sci. Adv. 2021, 1, e2000031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlSalem, H.S.; Alharbi, S.N.; Abdel-Lateef, M.A.; Abdel-Rahim, R.D.; El-Koussi, W.M. Nanozyme activity of silver nanowires for colorimetric detection of bisphenol A following salting-out assisted liquid-liquid extraction. Talanta Open 2025, 12, 100587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharshan, G.A.; Uosif, M.A.; Abdel-Rahim, R.D.; Yousef, E.S.; Shaaban, E.R.; Nagiub, A.M. Developing a simple, effective, and quick process to make silver nanowires with a high aspect ratio. Materials 2023, 16, 5501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Feng, J.; Ma, X.; Wu, C.; Zhao, X. One-dimensional silver nanowires synthesized by self-seeding polyol process. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2012, 14, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johan, M.R.; Aznan, N.A.K.; Yee, S.T.; Ho, I.H.; Ooi, S.W.; Darman Singho, N.; Aplop, F. Synthesis and growth mechanism of silver nanowires through different mediated agents (CuCl2 and NaCl) polyol process. J. Nanomater. 2014, 2014, 105454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korte, K.E.; Skrabalak, S.E.; Xia, Y. Rapid synthesis of silver nanowires through a CuCl-or CuCl2-mediated polyol process. J. Mater. Chem. 2008, 18, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Rahim, R.D.; Nagiub, A.M.; Taher, M.A. Electrical and Optical Properties of Flexible Transparent Silver Nanowires electrodes. Int. J. Thin. Film. Sci. Technol 2022, 11, 123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Yin, Y.; Mayers, B.T.; Herricks, T.; Xia, Y. Uniform silver nanowires synthesis by reducing AgNO3 with ethylene glycol in the presence of seeds and poly (vinyl pyrrolidone). Chem. Mater. 2002, 14, 4736–4745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coskun, S.; Aksoy, B.; Unalan, H.E. Polyol synthesis of silver nanowires: An extensive parametric study. Cryst. Growth Des. 2011, 11, 4963–4969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.-S.; Lin, P.; Qi, X.; Yang, L. Finnis–Sinclair potentials for fcc Au–Pd and Ag–Pt alloys. Int. J. Mater. Res. 2011, 102, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Rahim, R.D.; Nagiub, A.M.; Pharghaly, O.A.; Taher, M.A. Optical properties for flexible and transparent silver nanowires electrodes with different diameters. Opt. Mater. 2021, 117, 111123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkir, M.; Khan, M.T.; Ashraf, I.; AlFaify, S.; El-Toni, A.M.; Aldalbahi, A.; Ghaithan, H.; Khan, A. Rapid microwave-assisted synthesis of Ag-doped PbS nanoparticles for optoelectronic applications. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 21975–21985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xia, Y. Gold and silver nanoparticles: A class of chromophores with colors tunable in the range from 400 to 750 nm. Analyst 2003, 128, 686–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Huang, Y.; Fan, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Yu, W.; Rasco, B.A.; Lai, K. Detection of prohibited fish drugs using silver nanowires as substrate for surface-enhanced Raman scattering. Nanomaterials 2016, 6, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizoń, A.; Tisończyk, J.; Gajewska, M.; Drożdż, R. Silver nanoparticles as a tool for the study of spontaneous aggregation of immunoglobulin monoclonal free light chains. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, B.; Gu, J.; Xu, C.; Zhang, S. Flexible transparent conductive films based on silver nanowires by ultrasonic spraying process. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2022, 33, 25939–25949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, X.; Hu, W.; Liao, Y.; He, Y.; Dong, B.; Zhao, M.; Ma, Y. SPR-enhanced Au@ Fe3O4 nanozyme for the detection of hydroquinone. Chemosensors 2023, 11, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Song, L.; Yin, J.-J.; He, W.; Wu, Y.; Gu, N.; Zhang, Y. Co3O4 nanoparticles with multi-enzyme activities and their application in immunohistochemical assay. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 1959–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Li, S.; Lyu, D.; Zhang, D.; Wu, X.; Xu, Q.-H. Aggregation induced emission enhancement by plasmon coupling of noble metal nanoparticles. Mater. Chem. Front. 2019, 3, 2421–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piella, J.; Bastús, N.G.; Puntes, V. Modeling the optical responses of noble metal nanoparticles subjected to physicochemical transformations in physiological environments: Aggregation, dissolution and oxidation. Z. Für Phys. Chem. 2017, 231, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Chen, C.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, J.-W.; Yu, S.-H. Structure–property relationship of assembled nanowire materials. Mater. Chem. Front. 2020, 4, 2881–2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Result |

|---|---|

| λmax | 650 nm |

| Linear range (µg/mL) | 0.08–0.8 |

| Slope | 0.8359 |

| SD of slope | 0.01366 |

| Intercept | 0.0769 |

| SD of intercept | 0.00663 |

| r | 0.9994 |

| r2 | 0.9989 |

| LOQ (ng/mL) | 79.4 |

| LOD (ng/mL) | 26.1 |

| Assay | µg/mL | Recovery ± SD | RSD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inter-day | 0.25 | 99.81 ± 1.57 | 1.57 |

| 0.5 | 98.11 ± 1.10 | 1.10 | |

| 0.75 | 101.93 ± 1.46 | 1.46 | |

| Intra-day | 0.25 | 101.48 ± 2.09 | 2.09 |

| 0.5 | 99.94 ± 2.03 | 2.03 | |

| 0.75 | 99.70 ± 1.69 | 1.69 |

| Variable | % Recovery ± SD * |

|---|---|

| Volume of TMB solution (1.0 mM) | |

| 270.0 µL | 100.43 ± 0.94 |

| 330.0 µL | 101.56 ± 1.51 |

| Volume of H2O2 solution (6.0% w/v) | |

| 170.0 μL | 99.44 ± 1.88 |

| 230.0 μL | 98.77 ± 1.55 |

| Volume of Ag-NWs | |

| 130.0 μL | 99.9 ± 1.7 |

| 170.0 μL | 98.24 ± 0.81 |

| Volume of acetate buffer (0.10 M) | |

| 350.0 µL | 101.43 ± 2.02 |

| 450.0 µL | 98.31 ± 1.58 |

| pH of the reaction environment | |

| 3.0 | 101.56 ± 1.22 |

| 4.0 | 97.91 ± 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

AlSalem, H.S.; Alharbi, S.N.; Abdel-Rahim, R.D.; Nagiub, A.M.; Abdel-Lateef, M.A. Silver Nanowires with Efficient Peroxidase-Emulating Activity for Colorimetric Detection of Hydroquinone in Various Matrices. Chemosensors 2025, 13, 415. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors13120415

AlSalem HS, Alharbi SN, Abdel-Rahim RD, Nagiub AM, Abdel-Lateef MA. Silver Nanowires with Efficient Peroxidase-Emulating Activity for Colorimetric Detection of Hydroquinone in Various Matrices. Chemosensors. 2025; 13(12):415. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors13120415

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlSalem, Huda Salem, Sara Naif Alharbi, Rabeea D. Abdel-Rahim, Adham M. Nagiub, and Mohamed A. Abdel-Lateef. 2025. "Silver Nanowires with Efficient Peroxidase-Emulating Activity for Colorimetric Detection of Hydroquinone in Various Matrices" Chemosensors 13, no. 12: 415. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors13120415

APA StyleAlSalem, H. S., Alharbi, S. N., Abdel-Rahim, R. D., Nagiub, A. M., & Abdel-Lateef, M. A. (2025). Silver Nanowires with Efficient Peroxidase-Emulating Activity for Colorimetric Detection of Hydroquinone in Various Matrices. Chemosensors, 13(12), 415. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors13120415