Spectrofluorometric and Colorimetric Determination of Gliquidone: Validation and Sustainability Assessments

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Apparatuses

2.2. Materials

- (a)

- Pure standard

- (b)

- Pharmaceutical formulation

- (c)

- Chemicals and reagents

- Methanol, acetonitrile, and acetone were of HPLC grade.

- TCNQ (0.35% W/V, 1.7 × 10−2 M). It is prepared by weighing the desired amount of TCNQ (CHROMASOLV®®, Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Seeze, Germany), dissolving in acetone, and diluting to the final volume. The solution should be newly prepared each day.

- Double-distilled water (Otsoka Pharmaceuticals, Cairo, Egypt).

- Sodium Hydroxide (0.1 M aqueous solution), sulfuric acid (0.1 M aqueous solution), sodium lauryl sulphate, tween 20, tween 80, potassium di-hydrogen orthophosphate, chloroform, acetone, ethanol and ethyl acetate (El-Nasr Pharmaceutical Chemicals Co., Cairo, Egypt).

- β-cycloextrin (Sigma-Aldrich Chemie Gmbh, Seeze, Germany).

- Human plasma was acquired from VACSERA (Giza, Egypt) as a gift.

2.3. Primary and Secondary Standard Solutions

- (a)

- 1 mg·mL−1 in methanol, GLI standard stock solution

- (b)

- 10 μg·mL−1 in methanol, GLI standard working solution

- (c)

- Stock standard solution of GLI (1.7 × 10−2 M) for the assessment of stoichiometry of the reaction

3. Descriptions of Procedures and Methods

3.1. Spectrofluorometric Method

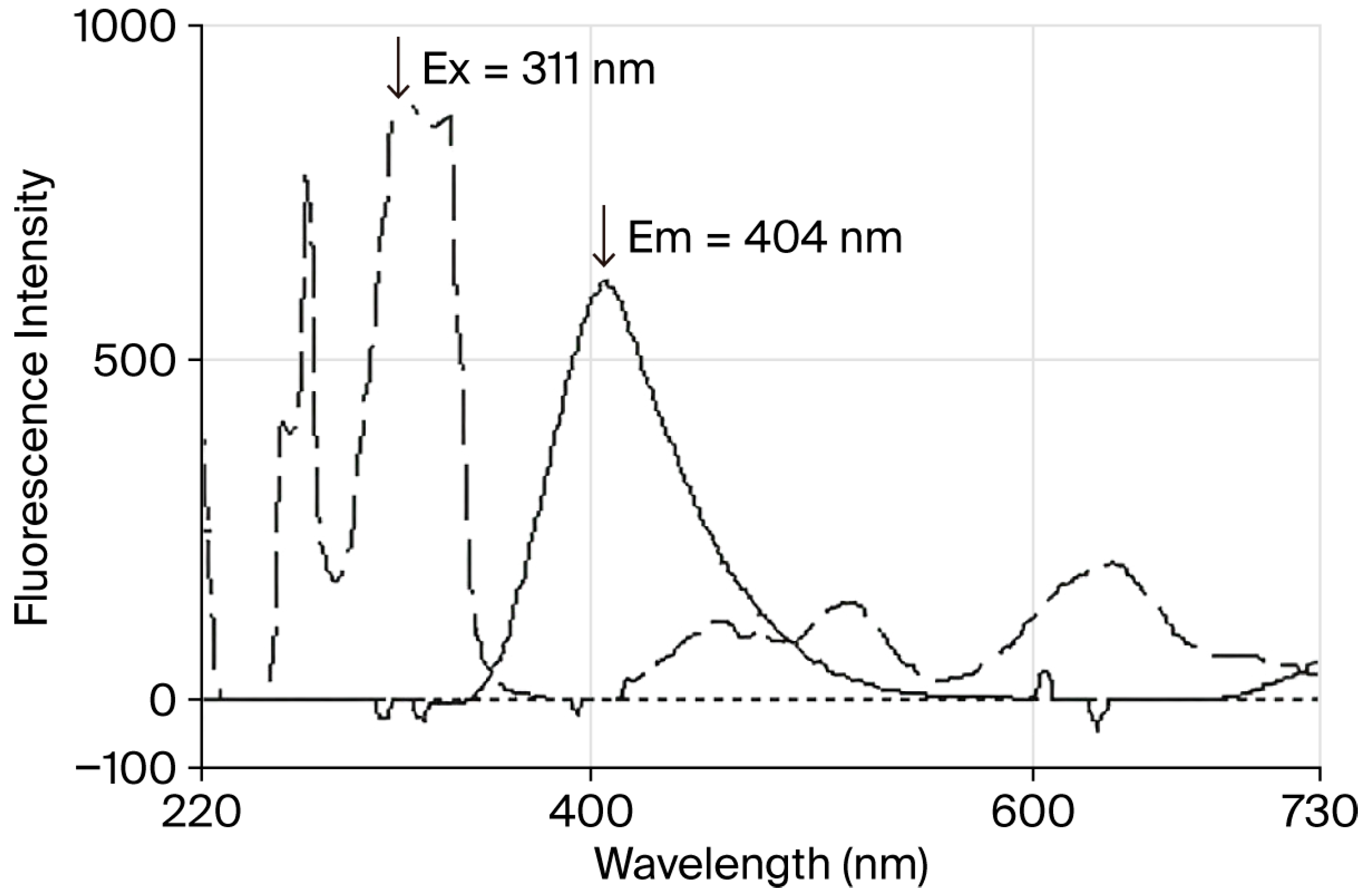

3.1.1. Optimization of Factors Affecting the Spectrofluorometric Method

- i.

- Solvent Selection

- ii.

- Optimization of Excitation Wavelength

- iii.

- Effect of pH

- iv.

- Effect of Surfactants (Micellar Media)

- v.

- Effect of β-Cyclodextrin

3.1.2. Application of the Spectrofluorometric Approach to Assess GLI in Human Plasma

3.2. The Spectrophotometric TCNQ Method

3.2.1. Spectral Characteristics of Gliquidone/TCNQ Reaction Products

3.2.2. Investigation of Various Items to Optimize Sensitivity and the Reaction Conditions

- (i)

- Effect of TCNQ concentration

- (ii)

- Effect of temperature on the development of green color products

- (iii)

- Investigation of heating time factor

- (iv)

- Investigation of various diluting solvent types on the absorbance intensity

- (v)

- Studying the effect of time on the stability of the Gliquidone/TCNQ complex

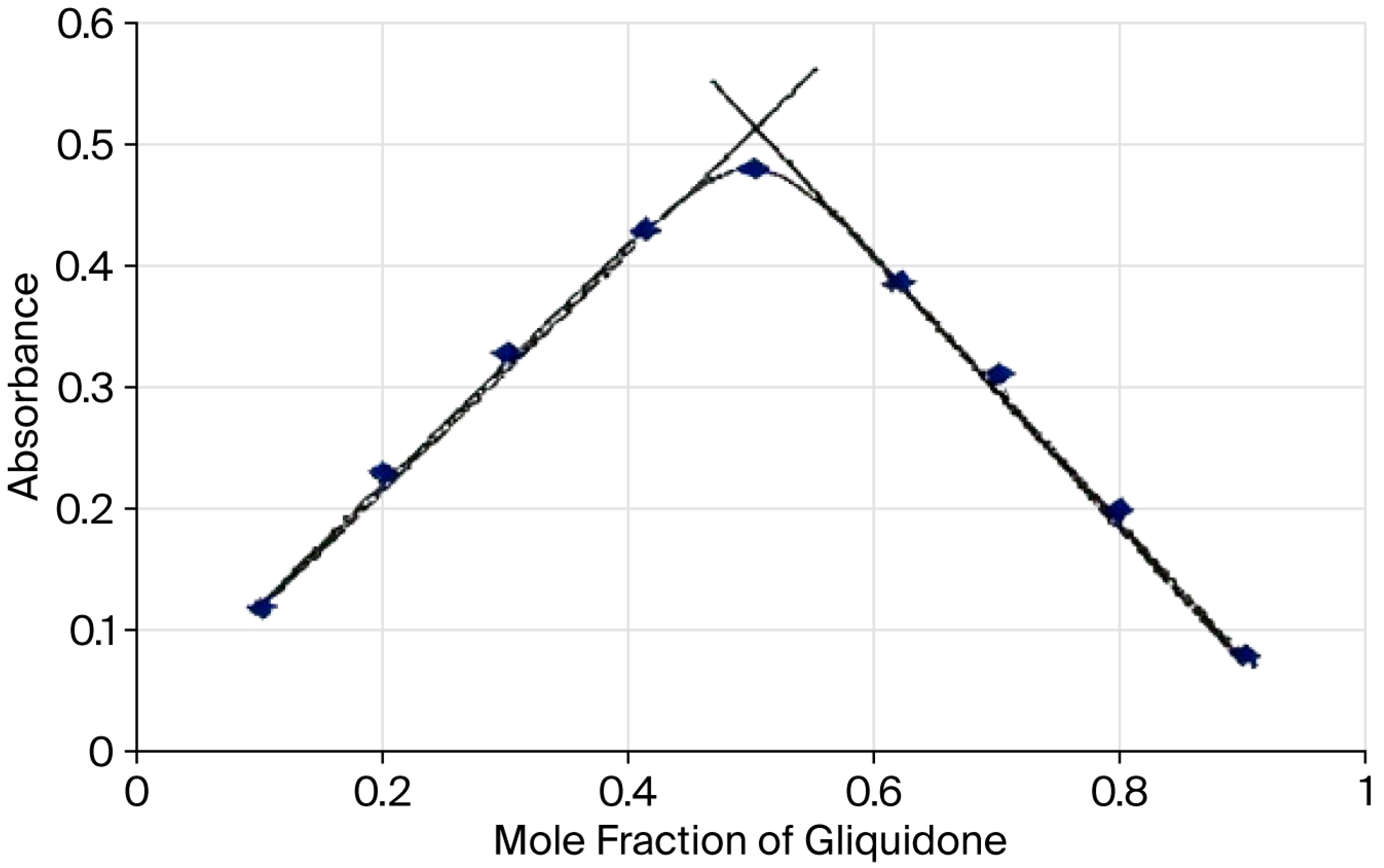

3.2.3. Evaluation of the Stoichiometry of the Gliquidone/TCNQ Reaction

3.2.4. Establishing the TCNQ Colorimetric Method’s Measurement Curve

3.2.5. Application to Pharmaceutical Formulation (Glurenor®® Tablets)

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Spectrofluorometric Approach

4.2. Colorimetric TCNQ Approach

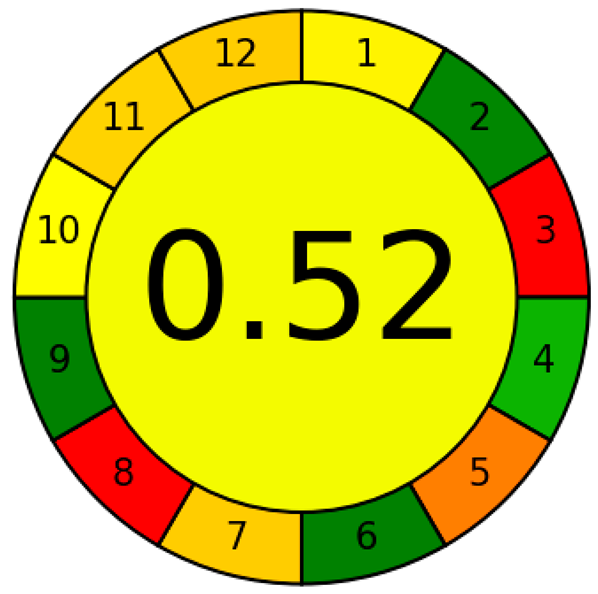

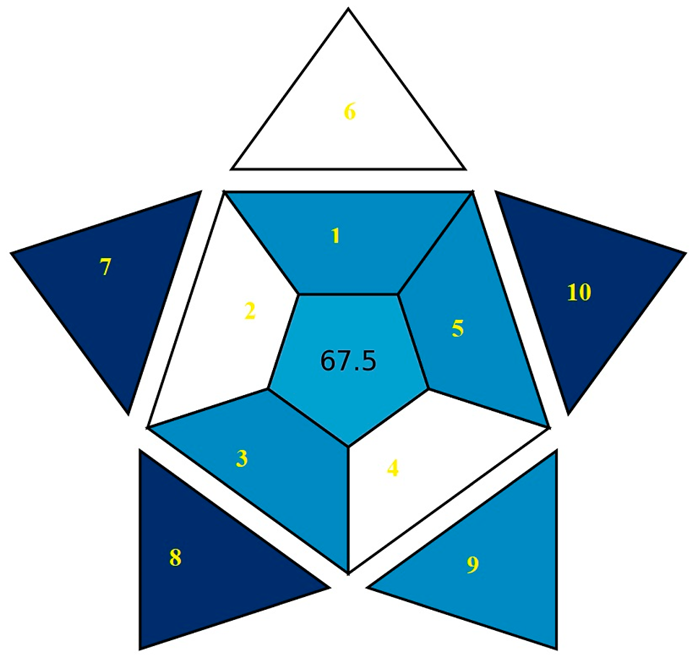

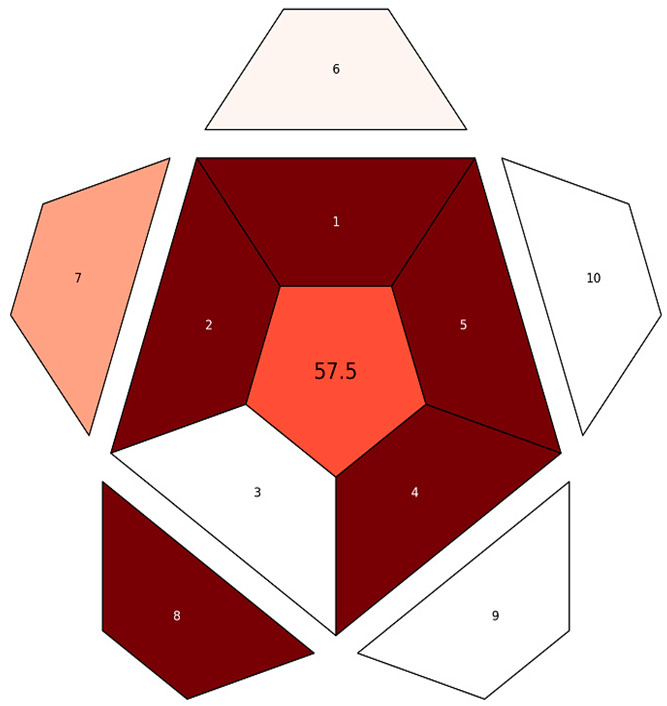

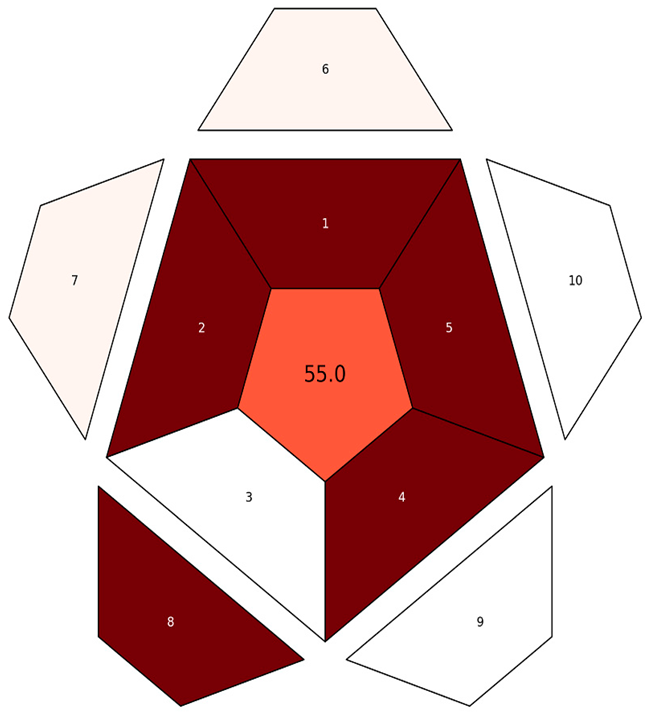

4.3. Greenness, Bluness, and Redness Assessments Using AGREE, BAGI, and RAPI Tools

4.4. Limitations and Future Plans

5. Conclusive Remarks

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- British Pharmacopoeia Commission, British Pharmacopoeia 2016; Stationery Office: London, UK, 2015.

- van Mil, J.W.F.; Brayfield, A. (Eds.) Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference 2014; Pharmaceutical Press: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Arayne, M.S.; Sultana, N.; Mirza, A.Z. Spectrophotometric Method for Quantitative Determination of Gliquidone in Bulk Drug, Pharmaceutical Formulations and Human Serum. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2006, 19, 185–189. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed Arayne, M.; Sultana, N.; Zeeshan Mirza, A. Preparation and Spectroscopic Characterization of Metal Complexes of Gliquidone. J. Mol. Struct. 2009, 927, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, N.; Yao, J.; Zhang, Q. TLC Method for Screening Sulphonylureas in Antidiabetics Chinese Traditional Patent Medicines and Health Supplementary Foods. Chin. J. Pharm. Anal. 2007, 27, 36–39. [Google Scholar]

- El-Ghobashy, M.R.; Yehia, A.M.; Helmy, A.H.; Youssef, N.F. Forced Degradation of Gliquidone and Development of Validated Stability-Indicating HPLC and TLC Methods. Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 54, e00223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelwahab, N.S.; Elsaady, M.T.; Korany, A.G.; Hegazy, M.A. Study of Gliquidone Degradation Behavior by High-Performance Thin-Layer Chromatography and Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography Methods. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2017, 31, e4025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, A.Z. HPLC-UV Method for Simultaneous Determination of Irbesartan, Candesartan, Gliquidone and Pioglitazone in Formulations and in Human Serum. J. Chin. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 27, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, A.Z.; Arayne, M.S.; Sultana, N. RP-LC Method for the Simultaneous Determination of Gliquidone, Pioglitazone Hydrochloride, and Atorvastatin in Formulations and Human Serum. J. AOAC Int. 2013, 96, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, A.Z.; Arayne, M.S.; Sultana, N. Method Development and Validation of Amlodipine, Gliquidone and Pioglitazone: Application in the Analysis of Human Serum. Anal. Chem. Lett. 2014, 4, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridevi, S.; Diwan, P.V. Validated HPLC Method for the Determination of Gliquidone in Rat Plasma. Pharm. Pharmacol. Commun. 2000, 6, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Li, Z.W.; Chen, C.H.; Deng, S.P.; Tang, S.G. [Direct Injection of Plasma to Determine Gliquidone in Plasma Using HPLC Column Switching Technique]. Acta Pharm. Sin. 1992, 27, 452–455. [Google Scholar]

- Arayne, M.S.; Sultana, N.; Mirza, A.Z.; Siddiqui, F.A. Validated RP-HPLC Method for Quantitation of Gliquidone in Pharmaceutical Formulation and Human Serum. J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 2010, 55, 156–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Shi, Y.Q.; Li, Z.R.; Jin, S.H. Development of a RP-HPLC Method for Screening Potentially Counterfeit Anti-Diabetic Drugs. J. Chromatogr. B Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2007, 853, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arayne, M.S.; Sultana, N.; Mirza, A.Z. Simultaneous Determination of Gliquidone, Pioglitazone Hydrochloride, and Verapamil in Formulation and Human Serum by RP-HPLC. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2011, 49, 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arayne, M.S.; Sultana, N.; Mirza, A.Z.; Siddiqui, F.A. Simultaneous Determination of Gliquidone, Fexofenadine, Buclizine, and Levocetirizine in Dosage Formulation and Human Serum by RP-HPLC. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2010, 48, 382–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Du, A.; Yang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, M.; Zhang, D.; Liu, H. Determination of Gliquidone in Human Plasma by LC-MS/MS and Bioequivalence Study of Its Two Tablets. Chin. J. Pharm. Anal. 2013, 33, 250–254. [Google Scholar]

- Maurer, H.H.; Kratzsch, C.; Kraemer, T.; Peters, F.T.; Weber, A.A. Screening, Library-Assisted Identification and Validated Quantification of Oral Antidiabetics of the Sulfonylurea-Type in Plasma by Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2002, 773, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, L.; Ling, X.; Sun, H. HPLC/MS2 Detection of Biguanides and Sulfonylurea Antidiabetics Illegally Mixed into Traditional Chinese Preparations. Chin. J. Pharm. Anal. 2008, 28, 1683–1685. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Zhang, X.; Luo, L.; Mu, H.; Li, W.; Wang, R. Effects of High-Altitude Environment on Pharmacokinetic Parameters of Gliquidone in Rats. J. Zhejiang Univ. (Med. Sci.) 2022, 51, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Xing, X.; Sun, R.; Yu, Z.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, P.; Xu, F. Gliquidone Alleviates DSS-Induced Ulcerative Colitis in Rats by Targeting Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase 1A. J. Pharm. Anal. 2025, 15, 101409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-ghobashy, M.R.; Yehia, A.M.; Helmy, A.H.; Youssef, N.F. Application of Normal Fluorescence and Stability-Indicating Derivative Synchronous Fluorescence Spectroscopy for the Determination of Gliquidone in Presence of Its Fluorescent Alkaline Degradation Product. Spectrochim. Acta—Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2018, 188, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imam, M.S.; Abdelrahman, M.M. How Environmentally Friendly Is the Analytical Process? A Paradigm Overview of Ten Greenness Assessment Metric Approaches for Analytical Methods. Trends Environ. Anal. Chem. 2023, 38, e00202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Płotka-Wasylka, J.; Mohamed, H.M.; Kurowska-Susdorf, A.; Dewani, R.; Fares, M.Y.; Andruch, V. Green Analytical Chemistry as an Integral Part of Sustainable Education Development. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2021, 31, 100508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Płotka-Wasylka, J.; Fabjanowicz, M.; Kalinowska, K.; Namieśnik, J. History and Milestones of Green Analytical Chemistry. In Green Analytical Chemistry; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Sajid, M.; Płotka-Wasylka, J. Green Analytical Chemistry Metrics: A Review. Talanta 2022, 238, 123046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelgawad, M.A.; Abdelaleem, E.A.; Gamal, M.; Abourehab, M.A.S.; Abdelhamid, N.S. A New Green Approach for the Reduction of Consumed Solvents and Simultaneous Quality Control Analysis of Several Pharmaceuticals Using a Fast and Economic RP-HPLC Method; a Case Study for a Mixture of Piracetam, Ketoprofen and Omeprazole Drugs. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 16301–16309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pena-Pereira, F.; Wojnowski, W.; Tobiszewski, M. AGREE—Analytical GREEnness Metric Approach and Software. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 10076–10082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manousi, N.; Wojnowski, W.; Płotka-Wasylka, J.; Samanidou, V. Blue Applicability Grade Index (BAGI) and Software: A New Tool for the Evaluation of Method Practicality. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 7598–7604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, P.M.; Wojnowski, W.; Manousi, N.; Samanidou, V.; Plotka-Wasylka, J. Red Analytical Performance Index (RAPI) and Software: The Missing Tool for Assessing Methods in Terms of Analytical Performance. Green Chem. 2025, 27, 5546–5553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamal, M.; Naguib, I.A.; Panda, D.S.; Abdallah, F.F. Comparative Study of Four Greenness Assessment Tools for Selection of Greenest Analytical Method for Assay of Hyoscine N -Butyl Bromide. Anal. Methods 2021, 13, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.J.; Kim, B.; Roh, E.; Kim, H.; Lee, S.H. Micellization-Induced Amplified Fluorescence Response for Highly Sensitive Detection of Heparin in Serum. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Jing, J.; Wang, D.; Tong, J.; Wang, N. Dye-Surfactant Solution of Coomassie Brilliant Blue G250 and Tween 20: Micellar and Interaction Parametric Studies. AATCC J. Res. 2019, 6, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, D.X.; Fan, L.W.; Ye, M.F.; Sun, W.Q.; Lin, R.L.; Liu, J.X. Supramolecular Inclusion Complexes of β-Cyclodextrin with Bathochromic-Shifted Photochromism and Photomodulable Fluorescence Enable Multiple Applications. Mater. Adv. 2023, 4, 5215–5223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakkialakshmi, S.; Menaka, T. Fluorescence Enhancement of Rhodamine 6G by Forming Inclusion Complexes with β-Cyclodextrin. J. Mol. Liq. 2011, 158, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nampally, V.; Palnati, M.K.; Baindla, N.; Varukolu, M.; Gangadhari, S.; Tigulla, P. Charge Transfer Complex between O-Phenylenediamine and 2, 3-Dichloro-5, 6-Dicyano-1, 4-Benzoquinone: Synthesis, Spectrophotometric, Characterization, Computational Analysis, and Its Biological Applications. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 16689–16704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.W.; Elghobashy, M.R.; Mahmoud, M.G.; Mohammed, M.A. Spectrophotometric and Spectrofluorimetric Methods for Determination of Racecadotril. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 24, 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Salem, H.; Mazen, D.Z.; Heshmat, D.; Mahmoud, M.M.; Ali, E.; Abdelaziz, A. Development and Validation of Three Colorimetric Charge Transfer Complexes for Estimation of Fingolimod as an Antineoplastic Drug in Pharmaceutical and Biological Samples. Chem. Pap. 2022, 76, 6675–6681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng-Yun, L.; Yu-Cui, H. Spectrophotometric Study of the Charge Transfer Complexation of Tranexamic Acid with 7,7,8,8-Tetracyanoquinodimethane. Bull. Chem. Soc. Ethiop. 2014, 28, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Schuster, P. The Donor-Acceptor Approach to Molecular Interactions. Fluid Phase Equilib. 1979, 3, 251–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.Y. [27] Determination of Binding Stoichiometry by the Continuous Variation Method: The Job Plot. Methods Enzymol. 1982, 87, 509–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazhin, N.M. Standard and Transformed Values of Gibbs Energy Formation for Some Radicals and Ions Involved in Biochemical Reactions. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2020, 686, 108282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Taken (µg·mL−1) | Found (µg·mL−1) | Recovery % |

|---|---|---|

| 0.05 | 0.050 | 100.00 |

| 0.10 | 0.102 | 102.00 |

| 0.15 | 0.148 | 98.66 |

| 0.20 | 0.199 | 99.50 |

| 0.25 | 0.250 | 100.00 |

| 0.30 | 0.298 | 99.33 |

| 0.35 | 0.351 | 100.28 |

| 0.40 | 0.398 | 99.50 |

| 0.45 | 0.451 | 100.22 |

| Mean ± SD | 100.00 ± 0.92 | |

| Taken (µg·mL−1) | Found (µg·mL−1) | Recovery % |

|---|---|---|

| 0.10 | 0.099 | 99.00 |

| 0.15 | 0.155 | 103.33 |

| 0.20 | 0.199 | 99.50 |

| 0.25 | 0.244 | 97.60 |

| 0.30 | 0.299 | 99.66 |

| 0.35 | 0.348 | 99.42 |

| 0.40 | 0.403 | 100.75 |

| Mean ± SD | 99.5 ± 1.78 | |

| Glurenor®® tablets containing 30 mg GLI/tablet (Batch No. ALE2857) | Technique | Taken (µg·mL−1) | Found % ± SD | Standard addition procedures Mean ± SD |

| Spectrofluorometric approach | 0.20 | 100.00 ± 0.84 | 99.83 ± 1.62 | |

| TCNQ colorimetric approach | 50.00 | 101.84 ± 1.14 | 99.98 ± 0.92 |

| Criteria | Spectrofluorometric Approach | TCNQ Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Range | 0.05–0.45 µg·mL−1 | 20–200 µg·mL−1 |

| Regression equation | ||

| Slope | 21.0775 | 0.0051 |

| Intercept | −0.04746 | 0.2773 |

| Correlation coefficient | 0.9999 | 0.9997 |

| Accuracy (Mean ± SD) | 100.43 ± 0.88 | 101.10 ± 1.27 |

| LOD | 0.015 | 6.05 |

| LOQ ** | 0.04 | 18 |

| Precision (RSD%) | ||

| Repeatability * | 0.74 | 0.55 |

| Intermediate precision * | 0.85 | 0.63 |

| Items | Spectrofluorometric Method | TCNQ Method | Reported Method * [3] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 100.00 | 101.10 | 100.16 |

| SD | 0.92 | 1.27 | 0.89 |

| RSD% | 0.920 | 1.256 | 0.888 |

| n | 9 | 8 | 6 |

| Variance | 0.846 | 1.613 | 0.729 |

| Student’s t-test | 0.067 (2.144) | 1.114 (2.160) ** | |

| F-value | 1.065 (4.146) | 2.017 (4.206) |

| Items | Spectrofluorometric Method | TCNQ Method | Reported Method * [3] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 100.00 | 101.84 | 100.62 |

| SD | 0.84 | 1.14 | 1.49 |

| RSD% | 0.840 | 1.119 | 1.481 |

| n | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Variance | 0.706 | 1.299 | 2.220 |

| Student’s t-test | 0.629 (2.228) | 1.904 (2.228) ** | |

| F-value | 2.660 (5.050) | 1.725 (5.050) |

| Assessment Tools | Spectrofluorometric Method | TCNQ Colorimetric Method |

|---|---|---|

| AGREE |  |  |

| AGREE subdivisions explanations | 1. Sample treatment, 2. Sample amount, 3. Device position, 4. Sample preparation steps, 5. Automation and miniaturization approaches, 6. Derivatization, 7. The chemical waste, 8. Analysis throughput, 9. The energy consumption, 10. Source of reagents, 11. Toxicity, 12. Analyst’s safety. | |

| BAGI |  |  |

| BAGI subdivisions explanations | 1. Analysis type, 2. Number of analyzed elements, 3. Number of samples, 4. Number of samples simultaneously prepared, 5. Sample preparation steps, 6. Number of samples assessed per hour, 7. The availability of reagents and chemicals, 8. The preconcentration steps, 9. The automation of analytical instrument, 10. Amount of pharmaceutical samples. | |

| RAPI |  |  |

| RAPI subdivisions explanations | 1. Repeatability, 2. Intermediate precision, 3. Reproducibility, 4. Trueness, 5. Recovery, matrix effect, 6. LOD, 7. Working range, 8. Linearity, 9. Ruggedness/robustness, 10. Selectivity | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Khateeb, L.A.; Abou El-Reash, Y.G.; Alotaibi, A.N.; Elamin, N.Y.; Ali, N.W.; Zaazaa, H.E.; Abdelkawy, M.; Magdy, M.A.; Gamal, M. Spectrofluorometric and Colorimetric Determination of Gliquidone: Validation and Sustainability Assessments. Chemosensors 2025, 13, 382. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors13110382

Al-Khateeb LA, Abou El-Reash YG, Alotaibi AN, Elamin NY, Ali NW, Zaazaa HE, Abdelkawy M, Magdy MA, Gamal M. Spectrofluorometric and Colorimetric Determination of Gliquidone: Validation and Sustainability Assessments. Chemosensors. 2025; 13(11):382. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors13110382

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Khateeb, Lateefa A., Yasmeen G. Abou El-Reash, Abdullah N. Alotaibi, Nuha Y. Elamin, Nouruddin W. Ali, Hala E. Zaazaa, Mohamed Abdelkawy, Maimana A. Magdy, and Mohammed Gamal. 2025. "Spectrofluorometric and Colorimetric Determination of Gliquidone: Validation and Sustainability Assessments" Chemosensors 13, no. 11: 382. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors13110382

APA StyleAl-Khateeb, L. A., Abou El-Reash, Y. G., Alotaibi, A. N., Elamin, N. Y., Ali, N. W., Zaazaa, H. E., Abdelkawy, M., Magdy, M. A., & Gamal, M. (2025). Spectrofluorometric and Colorimetric Determination of Gliquidone: Validation and Sustainability Assessments. Chemosensors, 13(11), 382. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors13110382