Factors beyond Workplace Matter: The Effect of Family Support and Religious Attendance on Sustaining Well-Being of High-Technology Employees

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Family Support, Work Engagement, and Subjective Well-Being

1.1.1. Family Support

1.1.2. Work Engagement

1.1.3. Subjective Well-Being

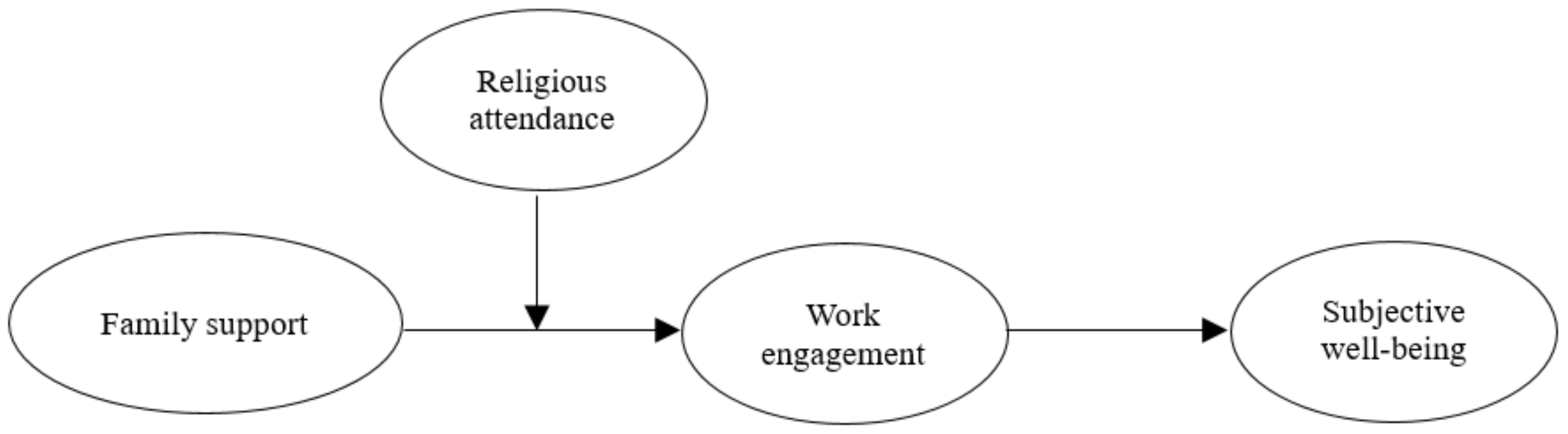

1.1.4. The Mediation Relationship

1.2. Moderating Effect of Religious Attendance

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measurements

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Assessment of Common Method Variance

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

3.2. Mediation Hypothesis Testing

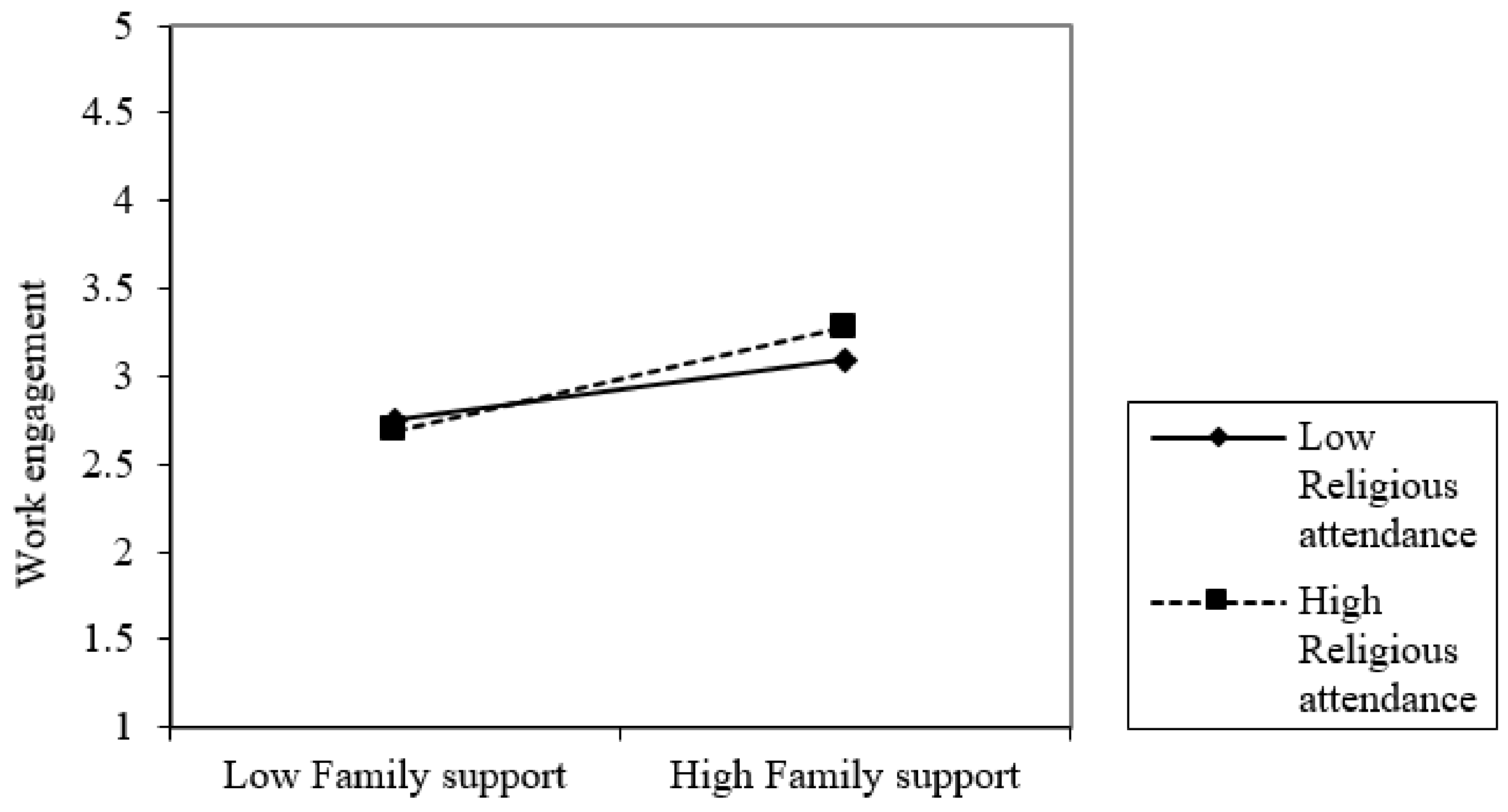

3.3. Moderated Mediation Hypothesis Testing

4. Discussion

4.1. Emphasizing the Driving Effect of Family Support on High-Technology Employee Well-Being

4.2. Emphasizing the Moderating Effect of Religious Attendance as a Situational Strength

5. Theoretical Implications

6. Practical Implications

7. Limitations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khoreva, V.; Wechtler, H. HR practices and employee performance: The mediating role of well-being. Empl. Relat. 2018, 40, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Yu, E. Follower strengths-based leadership and follower innovative behavior: The roles of core self-evaluations and psychological well-being. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2020, 36, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, T.A.; Cropanzano, R. Psychological well-being and job satisfaction as predictors of job performance. J. Occup. Health 2000, 5, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelenski, J.M.; Murphy, S.A.; Jenkins, D.A. The Happy-Productive Worker Thesis Revisited. J. Happiness Stud. 2008, 521–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lin, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, D.M. How do human resource management practices affect employee well-being? A mediated moderation model. Empl. Relat. 2020, 42, 903–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; González-Romá, V.; Bakker, A.B. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. Reciprocal relationships between job resources, personal resources and work engagement. J Vocat. Behav. 2009, 74, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. The impact of job crafting on job demands, job resources, and well-being. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2013, 18, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnettler, B.; Denegri, M.; Miranda, H.; Sepu’lveda, J.; Orellana, L.; Paiva, G.; Grunert, K.G. Family support and subjective well-being: An exploratory of university students in southern chile. Soc. Indic. Res. 2015, 122, 833–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toplu-Demirtas, E.; Kemer, G.; Pope, A.L.; Moe, J.L. Self-compassion matters: The relationships between perceived social support, self-compassion, and subjective well-being among LGB individuals in Turkey. J. Couns. Psychol. 2018, 65, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culbertson, S.S.; Mills, M.J.; Fullagar, C.J. Work engagement and work-family facilitation: Making Homes happier through positive affective spillover. Hum. Relat. 2012, 65, 1155–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, R.A.; Mills, M.; Trout, R.C.; English, L. Family-supportive supervisor behaviors, work engagement, and subjective well-being: A contextually dependent mediated process. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2014, 19, 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Verbeke, W. Using the job demands-resources model to predict brunout and performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2004, 43, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.M.; Zhang, R.P.; Cui, Q.; Hsu, S.-C. The antecedents of safety leadership: The job demands-resources model. Saf. Sci. 2021, 133, 104979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, Y.; Asakura, K.; Sugiyama, S.; Takada, N.; Ito, Y.; Nihei, Y. Nurses working in nursing homes: A mediation model for work engagement based on job demands-resources theory. Healthcare 2021, 9, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Chang, Y.K.; Kim, S. Are your vitals ok? Revitalizing vitality of nurses through relational caring for patients. Healthcare 2021, 9, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Aveni, R.A.; Dagnino, G.B.; Smith, K.G. The age of temporary advantage. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 1371–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Hernández, P.; Ramos, J.; Zornoza, A.; Lira, E.M.; Peiró, J.M. Mindfulness and job control as moderators of the relationship between demands and innovative work behaviours. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2020, 36, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döckel, A.; Basson, J.; Coetzee, M. The effect of retention factors on organizational commitment: An investigation of high technology employees. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2006, 4, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernyak-Hai, L.; Tziner, A. The “I believe” and the “I invest” of work-family balance: The indirect indirect influences of personal values and work engagement via perceived organizational climate and workplace burnout. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2016, 32, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, R.M.; Constantine, M.G. Multiple role balance, job satisfaction, and life satisfaction in woman school counselors. Prof. Sch. Couns. 2006, 9, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snir, R.; Harpaz, I.; Ben-Baruch, D. Centrality of and investment in work and family among Israeli high-tech workers: A bicultural perspective. Cross Cult. Res. 2009, 43, 366–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Hur, W.-M.; Choi, W.-H. Coworker support as a double-edged sword: A moderated mediation model of job crafting, work engagement, and job performance. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 31, 1417–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tews, M.J.; Michel, J.W.; Ellingson, J.E. The impact of coworker support on employee turnover in the hospitality industry. Group Organ. Manag. 2013, 38, 630–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poortvliet, P.M.; Janssen, O.; Van Yperen, N.W.; Van de Vliert, E. Low ranks make the difference: How achievement goals and ranking information affect cooperation intentions. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 45, 1144–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, S.M.; Wayne, S.J.; Liden, R.C.; Erdogan, B. Understanding social loafing: The role of justice perceptions and exchange relationships. Hum Relat. 2003, 56, 61–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Powell, G.N. When work and family are allies: A theory of work-family enrichment. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 72–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prazeres, F.; Passos, L.; Simões, J.A.; Simões, P.; Martins, C.; Teixeira, A. COVID-19-Related fear and anxiety: Spiritual-religious coping in healthcare workers in Portugal. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, L.G. A working model of health: Spirituality and religiousness as resources: Applications to persons with disability. J. Relig. Disabil. Health 2000, 3, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, K.C.; Gary, G.R. A framework for accommodating religion and spirituality in the workplace. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2000, 14, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, C.G. Religious involvement and subjective Well-Being. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1991, 32, 80–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo, G.A.; Ellison, C.G.; Xu, X. Is it really religion? Comparing the main and stress-buffering effects of religious and secular civic engagement on psychological distress. Soc. Ment. Health 2014, 4, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W. Religious attendance and subjective well-being in an eastern-culture country: Empirical evidence from Taiwan. Marbgurg J. Relig. 2009, 14, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappellen, P.V.; Toth-Gauthier, M.; Saroglou, V.; Fredrickson, B.L. Religion and well-being: The mediating role of positve emotions. J. Happiness Stud. 2016, 485–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, W.B.; Chaves, M.; Franz, D. Focused on the family? Religious traditions, family discourse, and pastoral practice. J. Sci. Stud. Relig. 2004, 43, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, G. The essntial impact of context on organizational behavior. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 386–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Hakanen, J.J.; Demerouti, E.; Xanthopoulou, D. Job resources boost work engagement particularly when job demands are high. J. Educ. Psychol. 2007, 99, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Towards a model of work engagement. Career Dev. Int. 2008, 13, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Näwall, K.; Sverke, M.; Göransson, S. Is work affecting my health? Appraisals of how work affects health as a mediator in the relationship between working conditions and work-related attitudes. Work Stress 2014, 28, 342–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Islam, T.; Usman, A. Predicting entrepreneurial intentions through self-efficacy, family support, and regret: A moderated mediation explanation. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2020, 13, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, Y.K.; Mukerjee, J.; Thurik, R. The role of family support in work-family balance and subjective well-being of SME owners. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2020, 58, 130–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decuypere, A.; Schaufeli, W. Leadership and work engagement: Exploring explanatory mechanisms. Ger. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 34, 69–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.-S.; Fellenz, M.R. Personal resources and personal demands for work engagement: Evidence from employees in the service industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 90, 102600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Lucas, R.E.; Oishi, S. Subjective Well-Being: The Science of Happiness and Life Satisfaction; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being. Psychol. Bull. 1984, 95, 542–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvishmotevali, M.; Ali, F. Job insecurity, subjective well-being and job performance: The moderating role of psychological capital. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 87, 102462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S. Recovery, work engagement, and proactive behavior: A new look at the interface between nonwork and work. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, J.H.; Randel, A.E.; Stevens, J. The role of identity and work-family support in work-family enrichment and its work-related consequences. J. Vocat. Behav. 2006, 69, 445–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William, K.J.; Alliger, G.M. Role stressors, mood spillover, and perceptions of work-family conflict in employed parents. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 837–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, K.Y.; Weng, C. Gratefulness and subjective well-being: Social connectedness and presence of meaning as mediators. J. Couns. Psychol. 2018, 65, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Levesque-Bristol, C.; Maeda, Y. General need for autonomy and subjective well-being: A meta-analysis of studies in the US and East Asia. J. Happiness Stud. 2018, 19, 1863–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L. “Culture fit”: Individual and societal discrepancies in values, beliefs, and subjective well-being. J. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 146, 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siedlecki, K.L.; Salthouse, T.A.; Oishi, S.; Jeswani, S. The relationship between social support and subjective well-being accross age. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 117, 561–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, P.P.; Colomeischi, A.A. Positivity ratio and well-being among teachers. The mediating role of work engagement. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, J.S.; Markides, K. Religious attendance and psychological well-being in middle-aged and older Mexican Americans. Sociol. Anal. 1988, 49, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, L.K.; Ellison, C.G.; Larson, D.B. Explaining the relationship between religious involvement and health. Psychol. Inq. 2002, 13, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, C.G.; Burdette, A.M.; Wilcox, W.B. The couple that prays together: Race, ethnicity, religion, and relationship quality among working-age adults. J. Marriage Fam. 2010, 72, 963–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.-Y.; Lin, J.-H.; Liu, S.-H. Coping with work-nonwork conflict and promoting life quality of frontline employees via social support. J. Manag. Syst. 2008, 15, 355–376. [Google Scholar]

- King, L.A.; Mattimore, L.K.; King, D.W.; Adams, G.A. Family support inventory for workers: A new measure of perceived social support from family member. J. Organ. Behav. 1995, 16, 235–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien, C.-L. The relationships between presidents’ authentic leadership and teachers’ organizational commitment in higher education: The mediation effect of teachers’ work engagement. Serv. Ind. Manag. Rev. 2012, 10, 67–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Hwang, M.-T.; Kao, S.-F. The Bi-directional conflict of work and family: Antecedents, consequences and moderators. Res. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 27, 133–166. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, L.; Gilmour, R.; Kao, S.; Huang, M. A cross-cultural study of work/family demands, work/family conflict and wellbeing: The Taiwanese vs. British. Career Dev. Int. 2006, 11, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presser, S.; Stinson, L. Estimating the bias in survey reports of religious attendance. In Survey Research Methods; American Statistical Association: Alexandria, VA, USA, 1996; pp. 932–938. [Google Scholar]

- Presser, S.; Stinson, L. Data collection mode and social desirability bias in self-reported religious attendance. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1998, 63, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuña, E.; Rodriguez, C. The treatment of missing values and its effect in the classifier accuracy. In Classification, Clustering and Data Mining Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbard, N.P. Enriching or Depleting? The dynamics of engagement in work and family roles. Adm. Sci. Q. 2001, 46, 655–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.; Yammarino, F.J.; Bass, B.M. Identifying common methods variance with data colleted from a single source: An unresolved sticky issue. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 571–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, N. Method Bias: The importance of theory and measurement. J. Organ. Behav. 1994, 15, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-reports in orgaizational research: Problems and prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, C.M.; Simmering, M.J.; Atinc, G.; Atinc, Y.; Babin, B.J. Common methods variance detection in business research. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3192–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nooney, J.G. Stress, and mental health in adolescence: Findings from Add Health. Rev. Relig. Res. 2005, 46, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauniar, R.; Rawski, G.; Yang, J.; Johnson, B. Technology acceptance model (TAM) and social media usage: An empirical study on Facebook. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2014, 27, 6–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, D.L.; Novak, T. Why do People Use Social Media? Empirical Findings and a New Theoretical Framework for Social Media Goal Pursuit. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1989586 (accessed on 23 January 2012).

- Avgoustaki, A.; Bessa, I. Examining the link between flexible working arrangement bundles and employee work effort. Hum. Res. Manag. 2019, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Kreiner, G.E.; Fugate, M. All in a day’s work: Boundaries and micro role transitions. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 472–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreiner, G.E. Consequences of work-home segmentation or integration: A person-environment fit perspective. J. Organ. Behav. 2006, 27, 485–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D.; Johnson, R.C.; Kiburz, K.M.; Shockley, K.M. Work–family conflict and flexible work arrangements: Deconstructing flexibility. Pers. Psychol. 2013, 66, 345–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugh, S.D.; Groth, M.; Hennig-Thurau, T. Willing and able to fake emotions: A closer examination of the link between emotional dissonance and employee well-Being. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 33.360 | 9.507 | — | ||||||

| 2. Gender | 0.577 | 0.494 | 0.215 ** | — | |||||

| 3. Tenure | 6.810 | 6.900 | 0.772 ** | 0.229 ** | — | ||||

| 4. Family support | 4.027 | 0.672 | 0.069 | 0.010 | 0.038 | — | |||

| 5. Work engagement | 3.348 | 0.655 | 0.149 ** | −0.040 | 0.055 | 0.368 ** | — | ||

| 6. Subjective well-being | 2.240 | 0.528 | 0.075 | −0.048 | 0.047 | 0.291 ** | 0.549 ** | — | |

| 7. Religious attendance | 0.272 | 0.445 | 0.163 ** | 0.108 ** | 0.125 ** | 0.087 * | 0.099 * | 0.114 ** | — |

| Variables | Work Engagement (M) | Subjective Well-Being (Y) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | SE | LLCI | ULCI | Coeff. | SE | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Work engagement (M) | 0.414 *** | 0.030 | 0.355 | 0.473 | ||||

| Family support (X) | 0.348 *** | 0.037 | 0.276 | 0.420 | 0.082 ** | 0.029 | 0.025 | 0.138 |

| Age (U1) | 0.016 *** | 0.004 | 0.008 | 0.024 | −0.003 | 0.003 | −0.009 | 0.003 |

| Gender (U2) | −0.086 | 0.051 | −0.187 | 0.014 | −0.035 | 0.037 | −0.108 | 0.039 |

| Tenure (U3) | −0.012 * | 0.006 | −0.023 | −0.001 | 0.004 | 0.004 | −0.004 | 0.013 |

| Constant | 1.539 *** | 0.180 | 1.187 | 1.892 | 0.601 *** | 0.139 | 0.328 | 0.874 |

| R2 | 0.162 *** | 0.313 *** | ||||||

| Indirect effects of X on Y | Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | ||||

| X → M → Y | 0.144 | 0.022 | 0.101 | 0.187 | ||||

| Variables | Work Engagement (M) | Subjective Well-Being (Y) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | SE | LLCI | ULCI | Coeff. | SE | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Work engagement (M) | 0.414 *** | 0.030 | 0.355 | 0.473 | ||||

| Family support (X) | 0.293 *** | 0.042 | 0.209 | 0.376 | 0.082 ** | 0.029 | 0.025 | 0.138 |

| Religious attendance (W) | −0.740 * | 0.346 | −1.420 | −0.060 | ||||

| X × W | 0.201 * | 0.084 | 0.036 | 0.365 | ||||

| Age (U1) | 0.016 *** | 0.004 | 0.008 | 0.024 | −0.003 | 0.003 | −0.009 | 0.003 |

| Gender (U2) | −0.093 | 0.051 | −0.193 | 0.007 | −0.035 | 0.037 | −0.108 | 0.039 |

| Tenure (U3) | −0.012 * | 0.006 | −0.023 | −0.001 | 0.004 | 0.004 | −0.004 | 0.013 |

| Constant | 1.758 *** | 0.198 | 1.369 | 2.147 | 0.601 *** | 0.139 | 0.328 | 0.874 |

| R2 | 0.173 *** | 0.313 *** | ||||||

| Conditional indirect effects of X on Y | Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | ||||

| Religious attendance (No) | 0.121 | 0.024 | 0.074 | 0.169 | ||||

| Religious attendance (Yes) | 0.204 | 0.034 | 0.142 | 0.273 | ||||

| Index of moderated mediation | Index | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | ||||

| X → M → Y by W | 0.083 | 0.037 | 0.015 | 0.159 | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, I.-C.; Du, P.-L.; Lin, L.-S.; Lin, T.-F.; Kuo, S.-C. Factors beyond Workplace Matter: The Effect of Family Support and Religious Attendance on Sustaining Well-Being of High-Technology Employees. Healthcare 2021, 9, 602. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9050602

Huang I-C, Du P-L, Lin L-S, Lin T-F, Kuo S-C. Factors beyond Workplace Matter: The Effect of Family Support and Religious Attendance on Sustaining Well-Being of High-Technology Employees. Healthcare. 2021; 9(5):602. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9050602

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Ing-Chung, Pey-Lan Du, Long-Sheng Lin, Tsai-Fei Lin, and Shu-Chun Kuo. 2021. "Factors beyond Workplace Matter: The Effect of Family Support and Religious Attendance on Sustaining Well-Being of High-Technology Employees" Healthcare 9, no. 5: 602. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9050602

APA StyleHuang, I.-C., Du, P.-L., Lin, L.-S., Lin, T.-F., & Kuo, S.-C. (2021). Factors beyond Workplace Matter: The Effect of Family Support and Religious Attendance on Sustaining Well-Being of High-Technology Employees. Healthcare, 9(5), 602. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9050602