Music Connects Us: Development of a Music-Based Group Activity Intervention to Engage People Living with Dementia and Address Loneliness

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Approach to Adaptation of Music for Life to Design Music Connects Us

2.1. Planning Meetings

2.1.1. Research and Program Presentations

2.1.2. Brainstorming and Discussion Sessions

2.1.3. Site Visits

2.2. Consultation with Musician Team Members

3. Products of the Adaptation Process

3.1. Description of Our Adapted Program: Music Connects Us

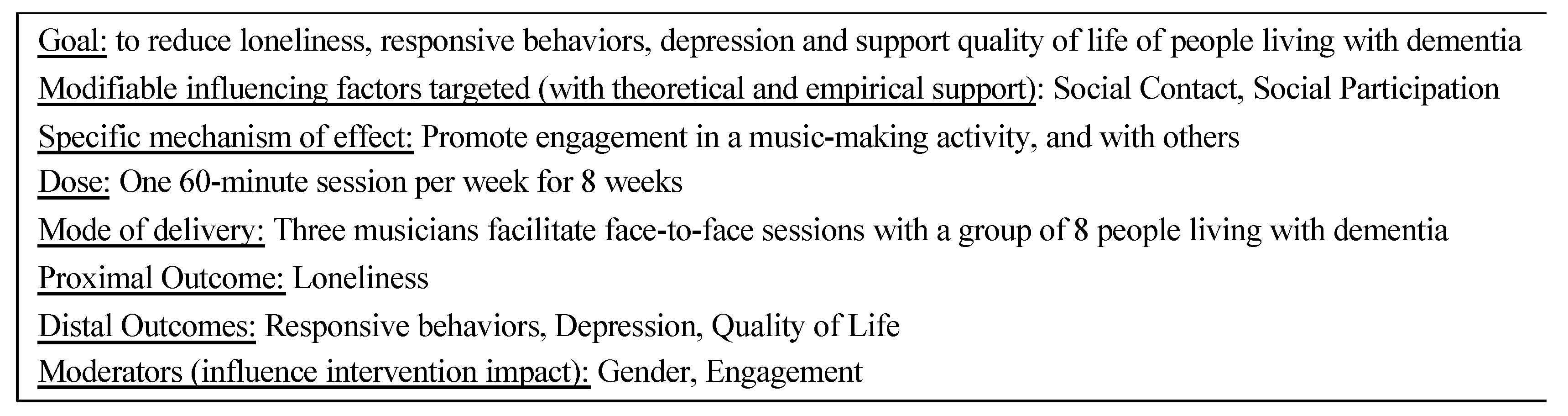

3.1.1. Goal and Components

3.1.2. Who Delivers Each Project?

3.1.3. Session Participants and Activities

3.1.4. Characteristics of the Facilitator

3.1.5. Musician Characteristics

3.1.6. Selecting Instruments for Residents

3.1.7. Activities to Support Sustainability

3.2. Summary of Adaptations Applied to Create Music Connects Us

3.2.1. Program Conceptualization and Framing

3.2.2. Reflective De-Brief Participants

3.2.3. Program Offerings per Care Home

3.2.4. Composition of Musician Group

3.2.5. Development of Training Program

4. Discussion

- What is the extent and nature of engagement behaviors and mood displayed during Music Connects Us sessions by men and women living with moderate to severe dementia in care homes?

- How do engagement behaviors change over the course of a 1-h session?

- What are the effects of musical engagement on people living with dementia? For example, can participating in a weekly session improve feelings of loneliness, and related outcomes like responsive behaviors, depression, and quality of life?

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Weiss, R.S. Loneliness: The Experience of Emotional and Social Isolation; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Victor, C.R. Loneliness in care homes: A neglected area of research? Aging Health 2012, 8, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackett, R.A.; Steptoe, A.; Cadar, D.; Fancourt, D. Social engagement before and after dementia diagnosis in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ericsson, I.; Hellström, I.; Kjellström, S. Sliding interactions: An ethnography about how persons with dementia interact in housing with care for the elderly. Dementia 2011, 10, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sadr, C.B.; Noureddine, S.; Kelley, J. Concept analysis of loneliness with implications for nursing diagnosis. Int. J. Nurs. Terminol. Classif. 2009, 20, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brownie, S.; Horstmanshof, L. The management of loneliness in aged care residents: An important therapeutic target for gerontological nursing. Geriatr. Nurs. 2011, 32, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyle, W.; Kellett, U.; Ballantyne, A.; Gracia, N. Dementia and loneliness: An Australian perspective. J. Clin. Nurs. 2011, 20, 1445–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Orden, K.A.; Stone, D.M.; Rowe, J.; McIntosh, W.L.; Podgorski, C.; Conwell, Y. The Senior Connection: Design and rationale of a randomized trial of peer companionship to reduce suicide risk in later life. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2013, 35, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, G. Predictors Associated with Late-Life Depressive Symptoms among Older Black Americans; ProQuest LLC: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Parpura-Gill, A. Loneliness in older persons: A theoretical model and empirical findings. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2007, 19, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, A.D.; Allaire, J.C. Cardiovascular intraindividual variability in later life: The influence of social connectedness and positive emotions. Psychol. Aging 2005, 20, 476–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, I.H.; Conwell, Y.; Bowen, C.; van Orden, K.A. Pet ownership may attenuate loneliness among older adult primary care patients who live alone. Aging Ment. Health 2014, 18, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerejeira, J.; Lagarto, L.; Mukaetova-Ladinska, E.B. Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Front. Neurol. 2012, 3, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, H.M.; Duggleby, W.; Fraser, K.D.; Jerke, L. Factors that affect quality of life from the perspective of people with dementia: A metasynthesis. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2015, 63, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, G.; Schaalma, H.; Ruiter, R.A.; van Empelen, P.; Brug, J. Intervention mapping: Protocol for applying health psychology theory to prevention programmes. J. Health Psychol. 2004, 9, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, D.; Cutrona, C.E.; Rose, J.; Yurko, K. Social and emotional loneliness: An examination of Weiss’s typology of loneliness. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 46, 1313–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perlman, D.; Peplau, L. Theoretical Approaches to Loneliness. In Loneliness: A Sourcebook of Current Theory, Research and Therapy; Perlman, D., Peplau, L., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1982; pp. 123–134. [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke, H.M.; Sidani, S. Definition, determinants and outcomes of social connectedness for older adults: A scoping review. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2017, 43, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornwell, B.; Laumann, E.; Schumm, L. The social connectedness of older adults: A national profile. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2008, 73, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warner, D.F.; Kelley-Moore, J. The social context of disablement among older adults: Does marital quality matter for loneliness? J. Health Soc. Behav. 2012, 53, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokach, A. The effect of gender and culture on loneliness: A mini review. Emerg. Sci. J. 2018, 2, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, H.; Collins, L.; Sidani, S. Interventions to address social connectedness and loneliness for older adults: A scoping review. BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitkala, K.H.; Routasalo, P.; Kautiainen, H.; Tilvis, R.S. Effects of psychosocial group rehabilitation on health, use of health care services, and mortality of older persons suffering from loneliness: A randomized, controlled trial. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2009, 64A, 792–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routasalo, P.E.; Tilvis, R.S.; Kautiainen, H.; Pitkala, K.H. Effects of psychosocial group rehabilitation on social functioning, loneliness and well-being of lonely, older people: Randomized controlled trial. J. Adv. Nurs. 2009, 65, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savikko, N.; Routasalo, P.; Tilvis, R.; Pitkälä, K. Psychosocial group rehabilitation for lonely older people: Favourable processes and mediating factors of the intervention leading to alleviated loneliness. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2010, 5, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winstead, V.; Yost, E.A.; Cotten, S.R.; Berkowsky, R.W.; Anderson, W.A. The impact of activity interventions on the well-being of older adults in continuing care communities. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2014, 33, 888–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Parpura-Gill, A.; Kotler, M.; Vass, J.; MacLennan, B.; Rosenberg, F. Shared interest groups (SHIGs) in low-income independent living facilities. Clin. Gerontol. 2007, 31, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, L. Intervention against loneliness in a group of elderly women: A process evaluation. Hum. Relat. 1984, 37, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, L. Intervention against loneliness in a group of elderly women: An impact evaluation. Soc. Sci. Med. 1985, 20, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, F.A.; Ballantyne, J. “You’ve got to accentuate the positive”: Group songwriting to promote a life of enjoyment, engagement and meaning in aging Australians. Nord. J. Music Ther. 2013, 22, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B.G.D. Research on creativity and aging: The positive impact of the arts on health and illness. Generations 2006, 30, 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, G.D.; Perlstein, S.; Chapline, J.; Kelly, J.; Firth, K.M.; Simmens, S. The impact of professionally conducted cultural programs on the physical health, mental health, and social functioning of older adults. Gerontologist 2006, 46, 726–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, V.M.; Allen, A.C.; Dwozan, M.; Mercer, I.; Warren, K. Indoor gardening and older adults: Effects on socialization, activities of daily living, and loneliness. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2004, 30, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queen, T.; Tawski, R.; Ryan, L.; Smith, J. Loneliness in a day: Activity engagement, time alone, and experienced emotions. Psychol. Aging 2014, 29, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clare, A.; Camic, P.M. Live and recorded group music interventions with active participation for people with dementias: A systematic review. Arts Health 2019, 12, 197–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozbe, D.; Graessel, E.; Donath, C.; Pendergrass, A.; Rouch, I. Immediate intervention effects of standardized multicomponent group interventions on people with cognitive impairment: A systematic review. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2019, 67, 653–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smilde, R.; Page, K.; Alheit, P. While the Music Lasts: On Music and Dementia; Eburon Academic Publishers: Groningen, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Baird, A.; Samson, S. Music and dementia. Prog. Brain Res. 2015, 217, 207–235. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Siegel, D.; Hartzell, M. Parenting from the Inside Out, 10th ed.; Penguin Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ueda, T.; Suzukamo, Y.; Sato, M.; Izumi, S.I. Effects of music therapy on behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2013, 12, 628–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, A.M.; Radanovic, M.; de Mello, P.C.; Buchain, P.C.; Vizzotto, A.D.; Celestino, D.L.; Stella, F.; Piersol, C.V.; Forlenza, O.V. Nonpharmacological interventions to reduce behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: A systematic review. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 218980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyer, S.M.; Harrison, S.L.; Laver, K.; Whitehead, C.; Crotty, M. An overview of systematic reviews of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for the treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2018, 30, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kverno, K.S.; Black, B.S.; Nolan, M.T.; Rabins, P.V. Research on treating neuropsychiatric symptoms of advanced dementia with non-pharmacological strategies, 19982008: A systematic literature review. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2009, 21, 825–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoi, K.K.F.; Chan, J.Y.C.; Ng, Y.M.; Lee, M.M.Y.; Kwok, T.C.Y.; Wong, S.Y.S. Receptive music therapy Is more effective than interactive music therapy to relieve behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2018, 19, 568–576.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, D.; Ames, D.; Gardner, B.; King, M. Psychosocial treatments of behavior symptoms in dementia: A systematic review of reports meeting quality standards. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2009, 21, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman-Evans, B. Beyond the basics: Effects of the Eden Alternative Model on quality of life issues. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2004, 30, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wigmore Hall Music for Life Programme Report: April 2015–July 2016. Available online: https://www.wigmore-hall.org.uk/learning/255-music-for-life-1516/file. (accessed on 11 May 2021).

- Clare, A.; Camic, P.M.; Crutch, S.J.; West, J.; Harding, E.; Brotherhood, E. Using music to develop a multisensory communicative environment for people with late-stage dementia. Gerontologist 2020, 60, 1115–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.; Graham, I.D.; Mrklas, K.J.; Bowen, S.; Cargo, M.; Estabrooks, C.A.; Kothari, A.; Lavis, J.; MacAulay, A.C.; MacLeod, M.; et al. How does integrated knowledge translation (IKT) compare to other collaborative research approaches to generating and translating knowledge? Learning from experts in the field. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2020, 18, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, S.J.; Graham, I.D. From knowledge translation to engaged scholarship: Promoting research relevance and utilization. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2013, 94, S3–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberta Health and Wellness Continuing Care Accommodation and Health Service Standards. Available online: http://www.health.alberta.ca/services/continuing-care-standards.html (accessed on 23 January 2018).

- Lawton, M.; van Haitsma, K.; Perkinson, M.; Ruckdeschel, K. Observed affect and quality of life in dementia: Further affirmations and problems. J. Ment. Health Aging 1999, 5, 69–81. [Google Scholar]

- Sidani, S.; Fox, M.; El-Masri, M. Guidance for the reporting of an intervention’s theory. Res. Theory Nurs. Pract. 2020, 34, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, L. Music for Life: A model for reflective practice. J. Dement. Care 2008, 16, 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Pringle, D. Making moments matter. Can. J. Nurs. Res. 2003, 35, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Foster, B.; Pearson, S.; Berends, A.; Mackinnon, C. The expanding scope, inclusivity, and integration of music in Healthcare: Recent developments, research illustration, and future direction. Healthcare 2021, 9, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, B.; Pearson, S.; Berends, A. 10 domains of Music Care: A framework for delivering music in Canadian healthcare settings (Part 3 of 3). Music Med. 2016, 8, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, L.K.; Parcel, G.S.; Kok, G. Intervention Mapping: A process for developing theory- and evidence-based health education programs. Health Educ. Behav. 1998, 25, 545–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, N.C.; Murray, E.; Darbyshire, J.; Emery, J.; Farmer, A.; Griffiths, F.; Guthrie, B.; Lester, H.; Wilson, P.; Kinmonth, A.L. Designing and evaluating complex interventions to improve health care. BMJ 2007, 334, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, P.; Dieppe, P.; Macintyre, S.; Michie, S.; Nazareth, I.; Petticrew, M. Medical Research Council Group. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new Medical Research Council guidance. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2013, 50, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidani, S.; Braden, C.J. Design, Evaluation, and Translation of Nursing Interventions; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: West Sussex, UK, 2011; ISBN 978-0-813-82032-3. [Google Scholar]

- Beulieu, M.; Breton, M.; Brouselle, A. Conceptualizing 20 years of engaged scholarship: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Technique | Description |

|---|---|

| Repetition | Repeating a sound, tone, melodic phrase or other musical material; involves improvising on a familiar musical style and genre to emphasize a feeling or idea to create rhythm. |

| Scaffolding | Adding new elements to repeated musical material to progress an improvised piece. |

| Modeling | Giving a clear example to follow, and most commonly used when introducing a new instrument. |

| Imitation | Where the musician mimics an exact copy of the resident’s presentation. |

| Mirroring | Copying the music that the resident plays and their body language. Used to encourage the resident to continue or expand upon their musical motif and promote empathetic connection. |

| Matching | Emulating the style and quality of music that a resident has played, to build upon what the resident has played in a congruous way. |

| Reflecting | Creating music that reflects the resident’s mood or underlying communication, as read by the musician; used to promote empathetic connection. |

| Translation | Playing music that validates what the resident has done, and then linking this to another type of musical contribution. |

| Hammer | A type of translation that creates a new energy and group dynamic. |

| Silence | Absence of sound and can be used before and after improvisations. It is powerful and allows time to recognize the resident’s engagement. |

| Singing | Use of the voice can be done at any time during the session in a strong voice with a good sense of pitch to engage or respond to the residents and make personal connections. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

O’Rourke, H.M.; Hopper, T.; Bartel, L.; Archibald, M.; Hoben, M.; Swindle, J.; Thibault, D.; Whynot, T. Music Connects Us: Development of a Music-Based Group Activity Intervention to Engage People Living with Dementia and Address Loneliness. Healthcare 2021, 9, 570. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9050570

O’Rourke HM, Hopper T, Bartel L, Archibald M, Hoben M, Swindle J, Thibault D, Whynot T. Music Connects Us: Development of a Music-Based Group Activity Intervention to Engage People Living with Dementia and Address Loneliness. Healthcare. 2021; 9(5):570. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9050570

Chicago/Turabian StyleO’Rourke, Hannah M., Tammy Hopper, Lee Bartel, Mandy Archibald, Matthias Hoben, Jennifer Swindle, Danielle Thibault, and Tynisha Whynot. 2021. "Music Connects Us: Development of a Music-Based Group Activity Intervention to Engage People Living with Dementia and Address Loneliness" Healthcare 9, no. 5: 570. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9050570

APA StyleO’Rourke, H. M., Hopper, T., Bartel, L., Archibald, M., Hoben, M., Swindle, J., Thibault, D., & Whynot, T. (2021). Music Connects Us: Development of a Music-Based Group Activity Intervention to Engage People Living with Dementia and Address Loneliness. Healthcare, 9(5), 570. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9050570