The Participation of Older People in the Concept and Design Phases of Housing in The Netherlands: A Theoretical Overview

Abstract

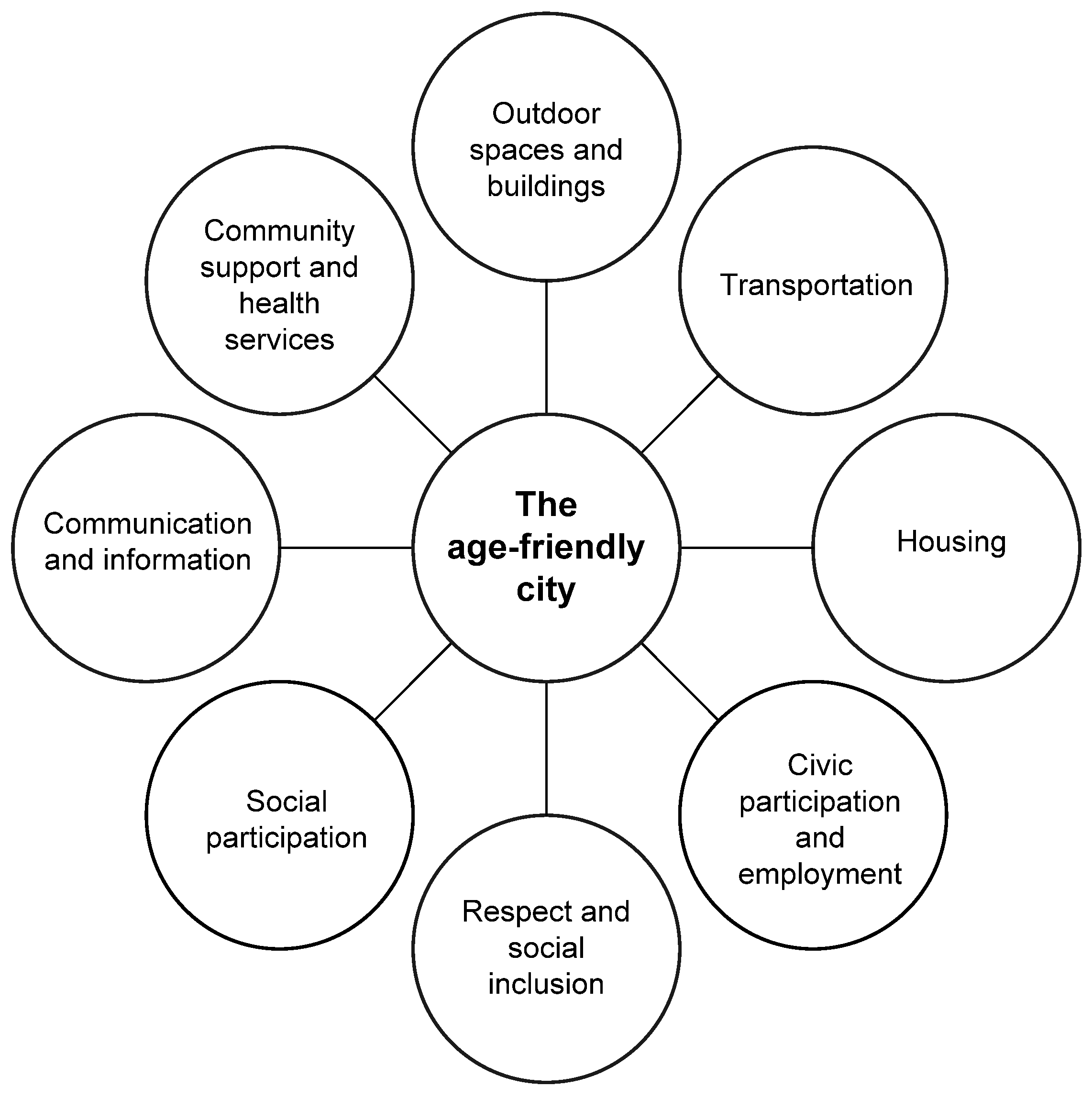

1. Introduction

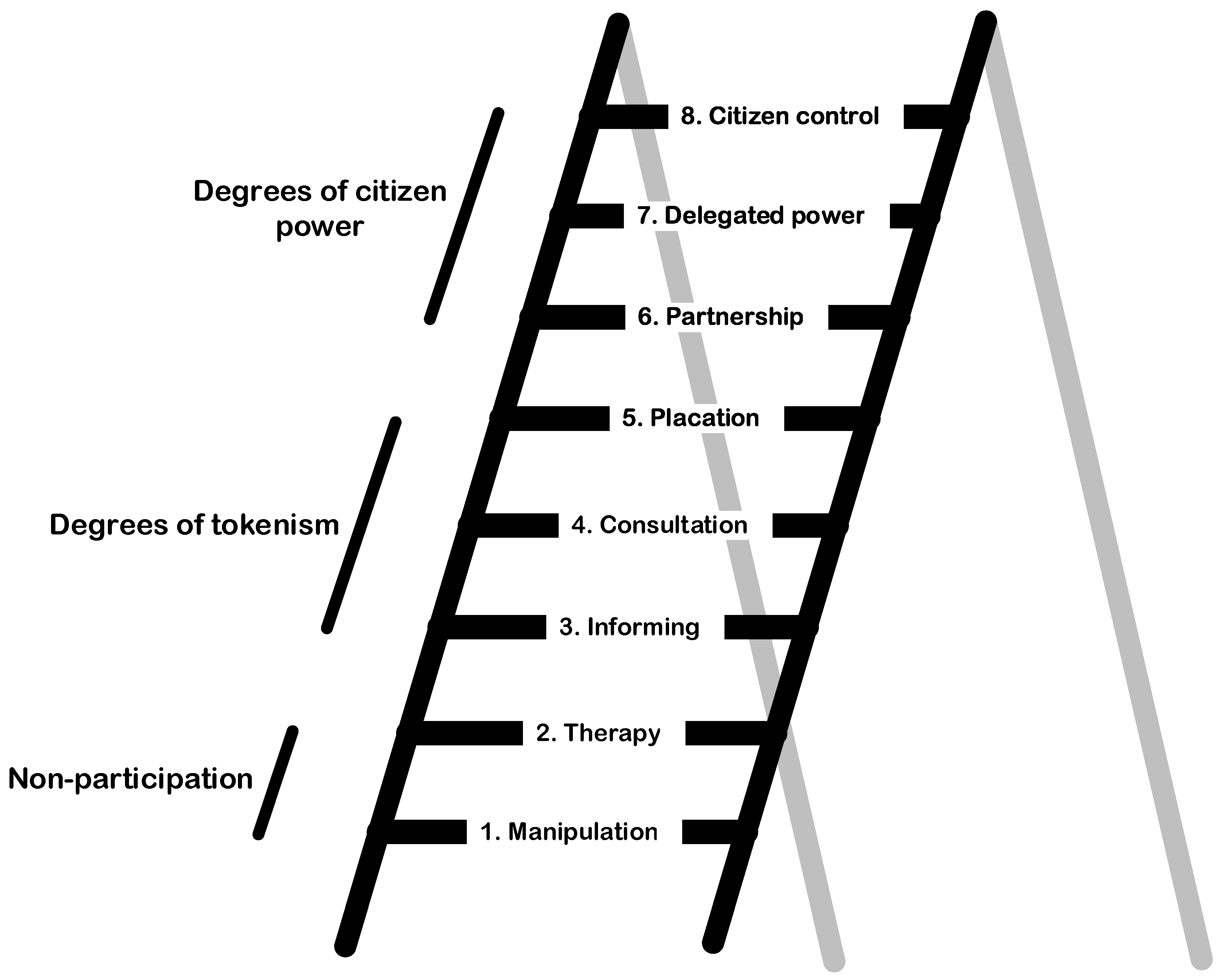

2. Levels of Participation

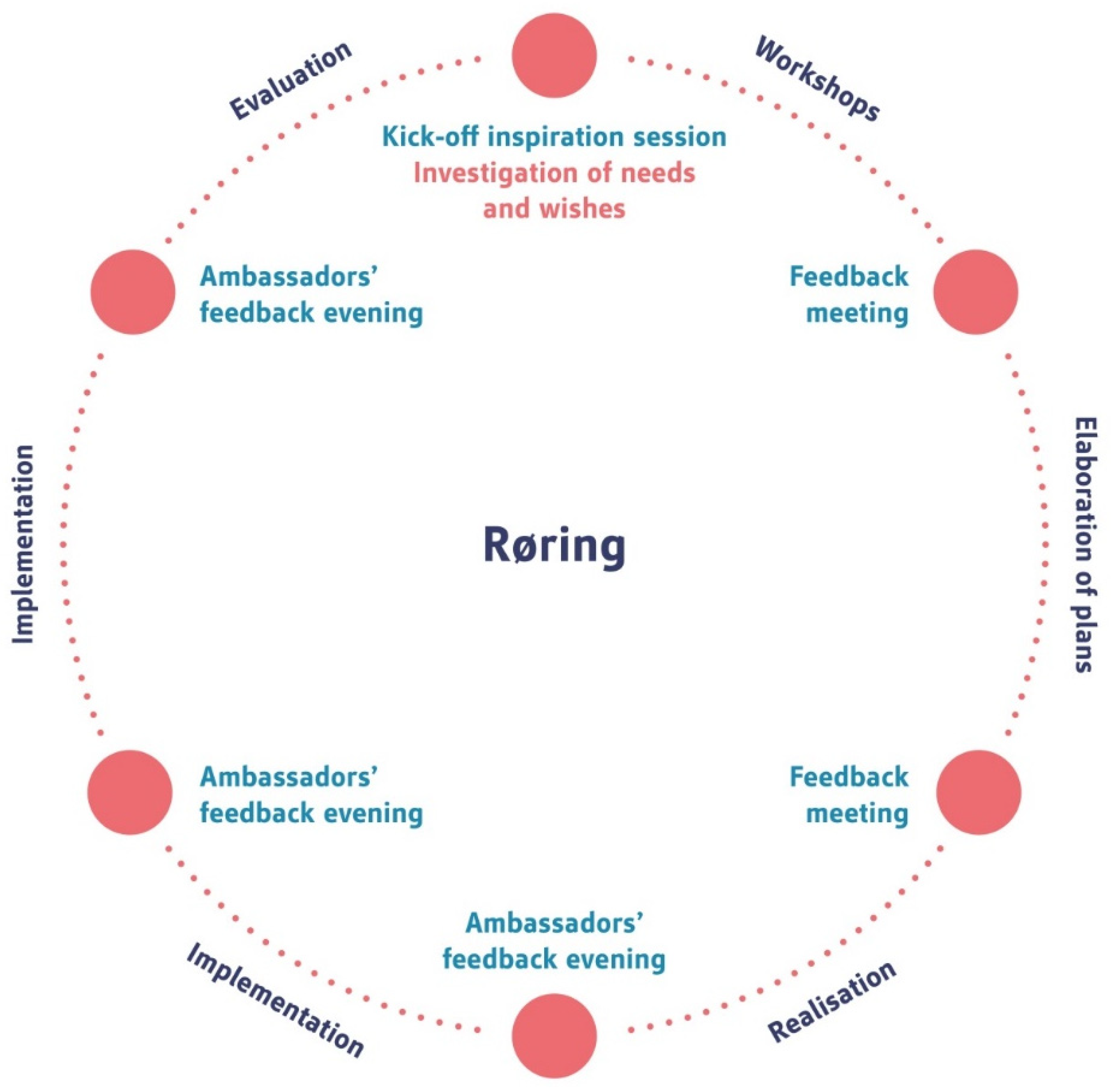

3. Examples of Participation in the Concept and Design Phases

4. What Do Older People Expect from Participation?

5. Factors That Impact the Participation of Older People

- Ensure staff provide supportive and facilitative leadership to citizens based on transparency;

- Foster a safe and trusting environment enabling citizens to provide input;

- Ensure citizens’ early involvement;

- Share decision-making and governance control with citizens;

- Acknowledge and address citizens’ experiences of power imbalances between citizens and professionals;

- Invest in citizens who feel they lack the skills and confidence to engage;

- Create quick and tangible wins;

- Take into account both citizens’ and organisations’ motivations.

- Recognition of the participation of older people, right from the start, as a prerequisite;

- Clear agreements about objectives, tasks, responsibilities and decision-making powers and evaluation of these agreements over time;

- Reservation of time and necessary resources to shape participation;

- Taking account of specific needs, ranging from the availability and accessibility of information to physical limitations or organisational capacity;

- Provision of necessary organisational, substantive and strategic support.

- Commitment of the organisation(s) involved to the objectives of the initiative and the willingness to cooperate with residents and to facilitate them;

- A clear picture of the existing situation; the living environment, the structures, the needs and preferences of residents;

- Formulation of clear and realistic goals, based on a clear understanding of the current situation;

- The presence of a group of motivated residents, who are open to new ideas, willing to offer space to other residents and, if necessary, to support them; who are able to set activities in motion and to attune them to the needs and pace of other residents and, by doing so, gain support for the initiative;

- Clear communication to residents, creating clarity about the background, objectives, tasks and responsibilities;

- The availability of an open and accessible common space where residents can meet;

- The support of a facilitating professional, aimed at activating and supporting the residents’ capacity for self-organisation.

6. Afterthoughts and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- OECD. Ageing in Cities; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2015; ISBN 9789264231146. [Google Scholar]

- van Hoof, J.; Kazak, J.K.; Perek-Białas, J.M.; Peek, S.T.M. The Challenges of Urban Ageing: Making Cities Age-Friendly in Europe. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Hoof, J.; Kazak, J.K. Urban ageing. Indoor Built Environ. 2018, 27, 583–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffel, T.; Phillipson, C. Can global cities be ‘age-friendly cities’? Urban development and ageing populations. Cities 2016, 55, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rémillard-Boilard, S.; Buffel, T.; Phillipson, C. Developing Age-Friendly Cities and Communities: Eleven Case Studies from around the World. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffel, T.; Phillipson, C.; Rémillard-Boilard, S. Age-Friendly Cities and Communities: New Directions for Research and Policy. In Encyclopedia of Gerontology and Population Aging; Gu, D., Dupre, M.E., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikken, J.; van den Hoven, R.F.M.; van Staalduinen, W.; Hulsebosch-Janssen, L.M.T.; van Hoof, J. How Older People Experience the Age-Friendliness of Their City: Development of the Age-Friendly Cities and Communities Questionnaire. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Hoof, J.; Marston, H.R. Age-Friendly Cities and Communities: State of the Art and Future Perspectives. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marston, H.R.; van Hoof, J. “Who Doesn’t Think about Technology When Designing Urban Environments for Older People?” A Case Study Approach to a Proposed Extension of the WHO’s Age-Friendly Cities Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Age-Friendly Cities: A Guide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007; ISBN 9789241547307. [Google Scholar]

- Doekhie, K.D.; de Veer, A.J.E.; Rademakers, J.J.D.J.M.; Schellevis, F.G.; Francke, A.L. Ouderen van de Toekomst Verschillen in de Wensen en Mogelijkheden Voor Wonen, Welzijn en Zorg: Overzichtstudies; Nivel: Utrech, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kazak, J.K.; van Hoof, J.; Świąder, M.; Szewrański, S. Real Estate for the Ageing Society—The Perspective of a New Market. Real Estate Manag. Valuat. 2017, 25, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hoof, J.; Boerenfijn, P. Re-Inventing Existing Real Estate of Social Housing for Older People: Building a New De Benring in Voorst, The Netherlands. Buildings 2018, 8, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusinovic, K.; van Bochove, M.; van de Sande, J. Senior Co-Housing in the Netherlands: Benefits and Drawbacks for Its Residents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusinovic, K.M.; van Bochove, M.E.; Koops-Boelaars, S.; Tavy, Z.K.C.T.; van Hoof, J. Towards Responsible Rebellion: How Founders Deal with Challenges in Establishing and Governing Innovative Living Arrangements for Older People. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport 2018, Programma Langer Thuis. The Hague, The Netherlands. Available online: https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/rapporten/2018/06/15/programma-langer-thuis (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Olde Bijvank, E.; Duivenvoorden, A.; van Triest, N. Opgave Wonen en Zorg in Beeld. Resultaten Landelijke Uitvraag: ‘Woonbehoefteonderzoeken Zorgdoelgroepen’; Platform 31: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Steels, S. Key characteristics of age-friendly cities and communities: A review. Cities 2015, 47, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, H.M. Neighbourhoods for Ageing in Place, Dissertation, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Rotterdam. 2015. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1765/78306 (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- de Weger, E.; van Vooren, N.; Luijkx, K.G.; Baan, C.A.; Drewes, H.W. Achieving successful community engagement: A rapid realist review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedding, C.; Slager, M. (Eds.) De rafels van Participatie in de Gezondheidszorg: Van Participerende Patiënt Naar Participerende Omgeving; Boom Lemma Uitgevers: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- van Hoof, J.; Zwerts-Verhelst, E.L.M.; Nieboer, M.E.; Wouters, E.J.M. Innovations in multidisciplinary education in healthcare and technology. Perspect. Med Educ. 2015, 4, 146–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Schrevel, S.; Slager, M.; de Vlugt, E. “I Stood by and Watched”: An Autoethnography of Stakeholder Participation in a Living Lab. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2020, 10, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Carmen Requena, M.; Swift, H.J.; Naegele, L.; Zwamborn, M.; Metz, S.; Bosems, W.P.H.; van Hoof, J. Chapter 23. Educational methods using intergenerational interaction to fight ageism. In Contemporary Perspectives on Ageism. International Perspectives on Aging; Ayalon, L., Tesch-Roemer, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Volume 19, pp. 383–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S.R. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michels, A. 2018, Burgerparticipatie in het beleid, bewonersinitiatieven, en de rol van de gemeenteraad. In De Gemeenteraad. Ontstaan en Ontwikkeling van de Lokale Democratie; Vollaard, H., Boogaard, G., van den Berg, J., Cohen, J., Eds.; Boom Uitgevers Amsterdam: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 199–205. [Google Scholar]

- PGO Support. De Participatieladder voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek. 2019. Available online: https://participatiekompas.nl/de-participatieladder-voor-wetenschappelijk-onderzoek (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Vossen, C.; Slager, M.; Wilbrink, N.; Roetman, A. Handboek Participatie Voor Ouderen in Zorg-en Welzijnsprojecten; CSO: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- van de Bovenkamp, H.; Vollaard, H.; Trappenburg, M.; Grit, K. Voice and choice by delegation. J. Health Politics Policy Law 2013, 38, 57–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hoof, J.; Verkerk, M.J. Developing an Integrated Design Model Incorporating Technology Philosophy for the Design of Healthcare Environments: A Case Analysis of Facilities for Psychogeriatric and Psychiatric Care in The Netherlands. Technol. Soc. 2013, 35, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hoof, J.; Rutten, P.G.S.; Struck, C.; Huisman, E.R.C.M.; Kort, H.S.M. The integrated and evidence-based design of healthcare environments. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2015, 11, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookfield, K.; Scott, I.; Tinker, A.; Ward Thompson, C. Perspectives on “Novel” Techniques for Designing Age-Friendly Homes and Neighborhoods with Older Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boerenfijn, P. Never waste a good crisis: How local communities successfully re-invent aged care facilities in the Netherlands. Gerontechnology 2017, 16, 239–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharra, R.; Nyssens, M. Social Innovation: An Interdisciplinary and Critical Review of the Concept; Université Catholique de Louvain: Ottignies-Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium, 2010; Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/b46a/2f4e83789220bda416fcb8ac01964156e73d.pdf?_ga=2.192641834.107980265.1579891237-472167725.1579891237 (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- von Faber, M.; Tavy, Z.; van der Pas, S. Engaging Older People in Age-Friendly Cities through Participatory Video Design. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagchus, C.; Dedding, C.; Bunders, J.F.G. ‘I’m happy that I can still walk’—Participation of the elderly in home care as a specific group with specific needs and wishes. Health Expect. 2015, 18, 2183–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groot, B.C.; Abma, T.A. Participatory Health Research with Older People in the Netherlands: Navigating Power Imbalances Towards Mutually Transforming Power. In Participatory Health Research; Wright, M.T., Kongats, K., Eds.; e-book; SpringerLink: Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, V.; Abma, T. ‘The Taste Buddies’: Participation and empowerment in a residential home for older people. Ageing Soc. 2012, 32, 1055–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montreuil, M.; Martineau, J.T.; Racine, E. Exploring Ethical Issues Related to Patient Engagement in Healthcare: Patient, Clinician and Researcher’s Perspectives. J. Bioethical Inq. 2019, 16, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CSO. Acht Keer Samenwerken. Ouderen en Onderzoekers over Participatie in Projecten. 2012. Available online: https://www.beteroud.nl/docs/beteroud/ouderenparticipatie/acht-keer-samenwerken-ouderen.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- CSO; Zorgbelang Nederland. Succesfactoren Ouderenparticipatie. 2012. Available online: https://www.beteroud.nl/docs/beteroud/ouderenparticipatie/succesfactoren-ouderenparticipatie.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- CSO; NOOM. Cliëntenparticipatie van Oudere Migranten, Factsheet. 2012. Available online: https://www.beteroud.nl/docs/beteroud/ouderenparticipatie/064_factsheet_diversiteit.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Machielse, A.; Bos, P.; Vaart, W.; van der Thoolen, E. Experiment Vitale Woongemeenschappen; Research Report; Platform 31: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Verdonschot, A.; Wagemakers, A.; den Broeder, L. Visie van professionals: Burgerparticipatie binnen Health Impact Assessment. Tijdschr. Gezondh. 2018, 96, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houwelingen, P.; Boele, A.; Dekker, P. Burgermacht op Eigen Kracht. The Netherlands Institute for Social Research. 2014. Available online: https://www.scp.nl/Publicaties/Alle_publicaties/Publicaties_2014/Burgermacht_op_eigen_kracht (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- RIVM. Available online: https://www.rivm.nl/en/about-rivm/knowledge-and-expertise/strategic-programme-rivm/2019-2022/environment-and-health (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- van Hoof, J.; Dikken, J.; Buttiġieġ, S.C.; van den Hoven, R.F.M.; Kroon, E.; Marston, H.R. Age-friendly cities in the Netherlands: An explorative study of facilitators and hindrances in the built environment and ageism in design. Indoor Built Environ. 2020, 29, 417–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.N. Age-ism: Another form of bigotry. Gerontologist 1969, 9, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, C.; Aitken, D.; Wilson, G.; Hodgson, P.; Douglas, B.; Docking, R. “What? That’s for Old People, that.” Home Adaptations, Ageing and Stigmatisation: A Qualitative Inquiry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, R.; Caulier-Grice, J.; Mulgan, G. The Open Book of Social Innovation; Social Innovator Series: Ways to Design, Develop and Grow Social Innovation; e-book; NESTA: London, UK, 2010; Available online: http://www.youngfoundation.org/files/images/Open_Book_of_Social_Innovation.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Kort, H.S.M.; Steunenberg, B.; van Hoof, J. Methods for Involving People Living with Dementia and Their Informal Carers as Co-Developers of Technological Solutions. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2019, 47, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

van Hoof, J.; Rusinovic, K.M.; Tavy, Z.K.C.T.; van den Hoven, R.F.M.; Dikken, J.; van der Pas, S.; Kruize, H.; de Bruin, S.R.; van Bochove, M.E. The Participation of Older People in the Concept and Design Phases of Housing in The Netherlands: A Theoretical Overview. Healthcare 2021, 9, 301. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9030301

van Hoof J, Rusinovic KM, Tavy ZKCT, van den Hoven RFM, Dikken J, van der Pas S, Kruize H, de Bruin SR, van Bochove ME. The Participation of Older People in the Concept and Design Phases of Housing in The Netherlands: A Theoretical Overview. Healthcare. 2021; 9(3):301. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9030301

Chicago/Turabian Stylevan Hoof, Joost, Katja M. Rusinovic, Zsuzsu. K. C. T. Tavy, Rudy F. M. van den Hoven, Jeroen Dikken, Suzan van der Pas, Hanneke Kruize, Simone R. de Bruin, and Marianne E. van Bochove. 2021. "The Participation of Older People in the Concept and Design Phases of Housing in The Netherlands: A Theoretical Overview" Healthcare 9, no. 3: 301. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9030301

APA Stylevan Hoof, J., Rusinovic, K. M., Tavy, Z. K. C. T., van den Hoven, R. F. M., Dikken, J., van der Pas, S., Kruize, H., de Bruin, S. R., & van Bochove, M. E. (2021). The Participation of Older People in the Concept and Design Phases of Housing in The Netherlands: A Theoretical Overview. Healthcare, 9(3), 301. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9030301