Bolstering General Practitioner Palliative Care: A Critical Review of Support Provided by Australian Guidelines for Life-Limiting Chronic Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

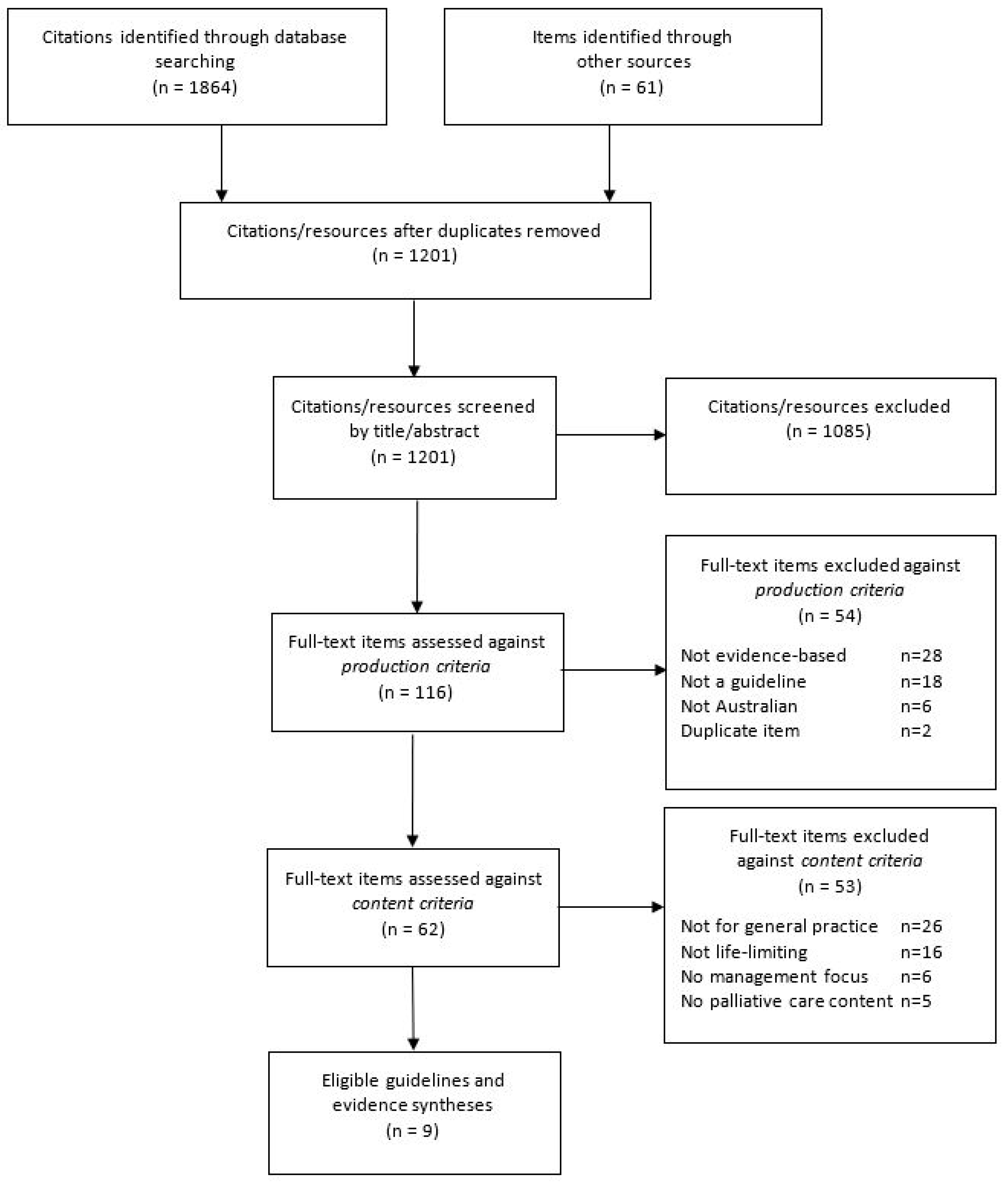

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search for Guidelines

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- Production criteria: Australian guidelines or evidence summaries, published since 2011, and reporting their methodology in full, including how the search for evidence was conducted and the basis used to formulate recommendations (e.g., consensus or evidence). The reporting criterion was important in ensuring all included guidelines were comparable in terms of their methodological and reporting quality.

- Content criteria: Explicitly relevant to primary care, focused on the management of a chronic life-limiting condition in adults (≥18 years), and including content on palliative or end-of-life care.

2.3. Quality Appraisal

2.4. Data Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Included Guidelines

3.2. Quality Appraisal

3.3. Mapping of Content to PEPSI-COLA Domains

3.3.1. Physical Needs

3.3.2. Emotional Needs

3.3.3. Personal Needs

3.3.4. Social Support Needs

3.3.5. Information and Communication

3.3.6. Control and Autonomy

3.3.7. Out of Hours

3.3.8. Late (Terminal) Care

3.3.9. After Care

3.4. Palliative Care Considerations Not Accommodated by PEPSI-COLA

3.4.1. Defining Palliative Care

3.4.2. The GP Role

3.4.3. Role of the Multidisciplinary Team

3.4.4. Prognostication Challenges

3.4.5. Timing the Initiation of a Palliative Care Approach

3.4.6. Benefits of Palliative Care

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Declaration of Astana. In Proceedings of the Global Conference on Primary Health Care, Astana, Kazakhstan, 25–26 October 2018; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Standards for General Practices, 5th ed.; RACGP: Melbourne, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann, A.; Carey, M.L.; Zucca, A.C.; Boyd, L.A.P.; Roberts, B.J. Australian GPs’ perceptions of barriers and enablers to best practice palliative care: A qualitative study. BMC Palliat. Care 2019, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, G.K.; Senior, H.E.; Johnson, C.E.; Fallon-Ferguson, J.; Williams, B.; Monterosso, L.; Rhee, J.J.; McVey, P.; Grant, M.P.; Aubin, M.; et al. Systematic review of general practice end-of-life symptom control. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2018, 8, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etkind, S.N.; Bone, A.E.; Gomes, B.; Lovell, N.; Evans, C.J.; Higginson, I.J.; Murtagh, F.E.M. How many people will need palliative care in 2040? Past trends, future projections and implications for services. BMC Med. 2017, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, C.E. The potential for a structured approach to palliative and end of life care in the community in Australia? Australas. Med. J. 2010, 3, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, G.K. Rapidly increasing end-of-life care needs: A timely warning. BMC Med. 2017, 15, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.; Manolova, G.; Daskalopoulou, C.; Vitoratou, S.; Prince, M.; Prina, A.M. Prevalence of multimorbidity in community settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J. Comorbidity 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palliative Care Australia. National Palliative Care Standards, 5th ed.; Palliative Care Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Green, E.; Knight, S.; Gott, M.; Barclay, S.I.; White, P. Patients’ and carers’ perspectives of palliative care in general practice: A systematic review with narrative synthesis. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 838–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.E.; McVey, P.; Rhee, J.J.-O.; Senior, H.; Monterosso, L.; Williams, B.; Fallon-Ferguson, J.; Grant, M.; Nwachukwu, H.; Aubin, M.; et al. General practice palliative care: Patient and carer expectations, advance care plans and place of death—A systematic review. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2018, 1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.E.; Senior, H.; McVey, P.; Team, V.; Mitchell, G. End-of-life care in rural and regional Australia: Patients’, carers’ and general practitioners’ expectations of the role of general practice, and the degree to which they were met. Health Soc. Care Community 2020, 28, 2160–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Health (Australia). Annual Medicare Statistics: Financial Year 1984–85 to 2017–18; DoH: Canberra, Australia, 2018.

- Rosenwax, L.K.; Spilsbury, K.; McNamara, B.A.; Semmens, J.B. A retrospective population based cohort study of access to specialist palliative care in the last year of life: Who is still missing out a decade on? BMC Palliat. Care 2016, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.K.J.; Rayson, D. The Coordination of Primary and Oncology Specialty Care at the End of Life. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2010, 2010, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, G.K.; Zhang, J.; Burridge, L.H.; Senior, H.E.; Miller, E.; Young, S.; Donald, M.; Jackson, C. Case conferences between general practitioners and specialist teams to plan end of life care of people with end stage heart failure and lung disease: An exploratory pilot study. BMC Palliat. Care 2014, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapsfield, J.; Hall, C.; Lunan, C.; McCutcheon, H.; McLoughlin, P.; Rhee, J.; Leiva, A.; Spiller, J.; Finucane, A.; Murray, S.A. Many people in Scotland now benefit from anticipatory care before they die: An after death analysis and interviews with general practitioners. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2016, 9, e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmont, S.-A.; Mitchell, G.; Senior, H.; Foster, M. Systematic review of the effectiveness, barriers and facilitators to general practitioner engagement with specialist secondary services in integrated palliative care. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2017, 8, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, G.K.; Del Mar, C.B.; O’Rourke, P.K.; Clavarino, A.M. Do case conferences between general practitioners and specialist palliative care services improve quality of life? A randomised controlled trial (ISRCTN 52269003). Palliat. Med. 2008, 22, 904–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.L.; Tarn, D.M. Effect of Primary Care Involvement on End-of-Life Care Outcomes: A Systematic Review. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2016, 64, 1968–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoonsen, B.; Vissers, K.C.; Verhagen, S.C.A.H.H.V.M.; Prins, J.B.; Bor, H.; Van Weel, C.; De Groot, M.C.H.; Engels, Y. Training general practitioners in early identification and anticipatory palliative care planning: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Fam. Pr. 2015, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, B.; Falster, M.O.; Girosi, F.; Jorm, L. Relationship between use of general practice and healthcare costs at the end of life: A data linkage study in New South Wales, Australia. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e009410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Palliative Care Services in Australia; AIHW: Canberra, Australia, 2020.

- Palliative Care Australia. Palliative Care Service Development Guidelines; Palliative Care Australia: Griffith, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Productivity Commission. Introducing Competition and Informed User Choice into Human Services: Reforms to Human Services; Report No. 85; Productivity Commission: Canberra, Australia, 2017.

- Coulton, C.; Boekel, C. Research into Awareness, Attitudes and Provision of Best Practice Advance Care Planning, Palliative Care and End of Life Care within General Practice; Department of Health (Australia): Canberra, Australia, 2017.

- Le, B.; Eastman, P.; Vij, S.; McCormack, F.; Duong, C.; Philip, J. Palliative care in general practice: GP integration in caring for patients with advanced cancer. Aust. Fam. Physician 2017, 46, 51–55. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, J.; Saunders, C.; Cook, A.; Johnson, C.E. End-of-life care in rural general practice: How best to support commitment and meet challenges? BMC Palliat. Care 2019, 18, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, J.; Zwar, N.; Vagholkar, S.; Dennis, S.; Broadbent, A.M.; Mitchell, G.K. Attitudes and Barriers to Involvement in Palliative Care by Australian Urban General Practitioners. J. Palliat. Med. 2008, 11, 980–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhee, J.; Grant, M.; Senior, H.; Monterosso, L.; McVey, P.; Johnson, C.E.; Aubin, M.; Nwachukwu, H.; Bailey, C.; Fallon-Ferguson, J.; et al. Facilitators and barriers to general practitioner and general practice nurse participation in end-of-life care: Systematic review. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2020, 2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royal Australian College of General Practitioners National Rural Faculty. Preliminary Results: RACGP National Rural Faculty (NRF) Palliative Care Survey; RACGP: East Melbourne, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Senior, H.; Grant, M.; Rhee, J.; Aubin, M.; McVey, P.; Johnson, C.; Monterosso, L.; Nwachukwu, H.; Fallon-Ferguson, J.; Yates, P.; et al. General practice physicians’ and nurses’ self-reported multidisciplinary end-of-life care: A systematic review. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2019, 1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, G.K. End-of-life care for patients with cancer. Aust. Fam. Physician 2014, 43, 514–519. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, G.K.; Burridge, L.H.; Colquist, S.P.; Love, A. General Practitioners’ perceptions of their role in cancer care and factors which influence this role. Health Soc. Care Community 2012, 20, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flierman, I.; Van Seben, R.; Van Rijn, M.; Poels, M.; Buurman, B.M.; Willems, D.L. Health Care Providers’ Views on the Transition Between Hospital and Primary Care in Patients in the Palliative Phase: A Qualitative Description Study. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2020, 60, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carduff, E.; Johnston, S.; Winstanley, C.; Morrish, J.; Murray, S.A.; Spiller, J.; Finucane, A.M. What does ‘complex’ mean in palliative care? Triangulating qualitative findings from 3 settings. BMC Palliat. Care 2018, 17, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, M.; Herrmann, A.; Freund, M.A.; Bryant, J.; Herrmann, A.; Roberts, B.J. Systematic review of barriers and enablers to the delivery of palliative care by primary care practitioners. Palliat. Med. 2019, 33, 1131–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crimmins, R.M.; Elliott, L.; Absher, D.T. Palliative Care in a Death-Denying Culture: Exploring Barriers to Timely Palliative Efforts for Heart Failure Patients in the Primary Care Setting. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2021, 38, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reymond, L.; Cooper, K.; Parker, D.; Chapman, M. End-of-life care: Proactive clinical management of older Australians in the community. Aust. Fam. Physician 2016, 45, 76–78. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Definition of Palliative Care. Available online: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/ (accessed on 21 December 2012).

- Appleby, A.; Wilson, P.; Swinton, J. Spiritual Care in General Practice: Rushing in or Fearing to Tread? An Integrative Review of Qualitative Literature. J. Relig. Health 2018, 57, 1108–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, B.; Varghese, F.T.; Burnett, P.; Turner, J.; Robertson, M.; Kelly, P.; Mitchell, G.K.; Treston, P. General practitioners’ experiences of the psychological aspects in the care of a dying patient. Palliat. Support. Care 2008, 6, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Murray, S.A.; Firth, A.; Schneider, N.; Eynden, B.V.D.; Gomez-Batiste, X.; Brogaard, T.; Villanueva, T.; Abela, J.; Eychmuller, S.; Mitchell, G.; et al. Promoting palliative care in the community: Production of the primary palliative care toolkit by the European Association of Palliative Care Taskforce in primary palliative care. Palliat. Med. 2015, 29, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deckx, L.; Mitchell, G.K.; Rosenberg, J.; Kelly, M.; Carmont, S.-A.; Yates, P. General practitioners’ engagement in end-of-life care: A semi-structured interview study. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2019, 1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battista, R.N.; Hodge, M.J. Clinical practice guidelines: Between science and art. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1993, 148, 385–389. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust; Graham, R., Mancher, M., Miller, W.D., Greenfield, S., Steinberg, E., Eds.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, G.K.; Aubin, M.; Senior, H.; Johnson, C.E.; Fallon-Ferguson, J.; Williams, B.; Monterosso, L.; Rhee, J.; McVey, P.; Grant, M.; et al. General practice nurses and physicians and end of life: A systematic review of models of care. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Highet, G.; Crawford, D.; A Murray, S.; Boyd, K. Development and evaluation of the Supportive and Palliative Care Indicators Tool (SPICT): A mixed-methods study. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2013, 4, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwers, M.C.; Kho, M.E.; Browman, G.P.; Burgers, J.S.; Cluzeau, F.; Feder, G.; Fervers, B.; Graham, I.D.; Grimshaw, J.; Hanna, S.E.; et al. AGREE II: Advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2010, 182, E839–E842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K. Holistic Patient Assessment: PEPSI COLA Aide Memoire. Available online: https://goldstandardsframework.org.uk/cd-content/uploads/files/Library%2C%20Tools%20%26%20resources/Pepsi%20cola%20aide%20memoire.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2020).

- Australian Adult Cancer Pain Management Guideline Working Party, Cancer Council Australia. Cancer Pain Management in Adults: Evidence-based Clinical Practice Guidelines Adapted for Use in Australia. Available online: https://wiki.cancer.org.au/australia/Guidelines:Cancer_pain_management (accessed on 31 October 2020).

- Guideline Adaptation Committee. Clinical Practice Guidelines and Principles of Care for People with Dementia; Guideline Adaptation Committee: Sydney, Australia, 2016; Available online: https://cdpc.sydney.edu.au/research/clinical-guidelines-for-dementia/ (accessed on 31 October 2020).

- Atherton, J.J.; Sindone, A.; De Pasquale, C.G.; Driscoll, A.; Macdonald, P.S.; Hopper, I.; Kistler, P.M.; Briffa, T.; Wong, J.; Abhayaratna, W.; et al. National Heart Foundation of Australia and Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand: Guidelines for the Prevention, Detection, and Management of Heart Failure in Australia 2018. Hear. Lung Circ. 2018, 27, 1123–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, E.; Farrell, B.; Thompson, W.; Herrmann, N.; Sketris, I.; Magin, P. Evidence-based Clinical Practice Guideline for Deprescribing Cholinesterase Inhibitors and Memantine. Available online: https://cdpc.sydney.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/deprescribing-guideline.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2020).

- Yang, I.; Dabscheck, E.; George, J.; Jenkins, S.; McDonald, C.; McDonald, V. The COPD-X Plan: Australian and New Zealand Guidelines for the Management of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2016. Available online: https://copdx.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/COPDX-V2-54-June-2018.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2020).

- Atherton, J.J.; Sindone, A.; Pasquale, C.G.D.; Driscoll, A.; MacDonald, P.S.; Hopper, I. National Heart Foundation of Australia and Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand: Australian clinical guidelines for the management of heart failure 2018. Med. J. Aust. 2018, 209, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, S.M.; Laver, K.; Pond, C.D.; Cumming, R.G.; Whitehead, C.; Crotty, M. Clinical practice guidelines and principles of care for people with dementia in Australia. Aust. Fam. Physician 2016, 45, 884–889. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yang, I.A.; Brown, J.L.; George, J.; Jenkins, S.; McDonald, C.F.; McDonald, V.M.; Phillips, K.; Smith, B.J.; Zwar, N.A.; Dabscheck, E. COPD-X Australian and New Zealand guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: 2017 update. Med. J. Aust. 2017, 207, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, I.A.; Dabscheck, E.J.; George, J.; Jenkins, S.C.; McDonald, C.F.; McDonald, V.M. COPD-X Concise Guide for Primary Care. Lung Foundation Australia: Brisbane, Qld, 2017. Available online: https://lungfoundation.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Book-COPD-X-Concise-Guide-for-Primary-Care-Jul2017.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2020).

- Birrenbach, T.; Kraehenmann, S.; Perrig, M.; Berendonk, C.; Huwendiek, S. Physicians’ attitudes toward, use of, and perceived barriers to clinical guidelines: A survey among Swiss physicians. Adv. Med. Educ. Pr. 2016, 7, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, H.R.; Deckx, L.; A Sieben, N.; Foster, M.M.; Mitchell, G.K. General practitioners’ considerations when deciding whether to initiate end-of-life conversations: A qualitative study. Fam. Pr. 2019, 37, 554–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trankle, S.A.; Shanmugam, S.; Lewis, E.; Nicholson, M.; Hillman, K.; Cardona, M. Are We Making Progress on Communication with People Who Are Near the End of Life in the Australian Health System? A Thematic Analysis. Health Commun. 2020, 35, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irving, G.; Holden, J.; Edwards, J.; Reeve, J.; Dowrick, C.; Lloyd-Williams, M. Chronic heart failure guidelines: Do they adequately address patient need at the end-of-life? Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 168, 2304–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koper, I.; Pasman, R.H.R.W.; Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B.B.D. Experiences of Dutch general practitioners and district nurses with involving care services and facilities in palliative care: A mixed methods study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durepos, P.; Wickson-Griffiths, A.; Hazzan, A.A.; Kaasalainen, S.; Vastis, V.; Battistella, L.; Pappaioannou, A. Assessing Palliative Care Content in Dementia Care Guidelines: A Systematic Review. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2017, 53, 804–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, N.; Costantini, M.; Pasman, H.; Block, L.V.D.; Donker, G.A.; Miccinesi, G.; Bertolissi, S.; Gil, M.; Boffin, N.; Zurriaga, O.; et al. End-of-Life Communication: A Retrospective Survey of Representative General Practitioner Networks in Four Countries. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2014, 47, 604–619.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Johnson, C.E.; Cook, A. How We Should Assess the Delivery of End-of-Life Care in General Practice: A Systematic Review. J. Palliat. Med. 2018, 21, 1790–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, Executive Board. Strengthening of Palliative Care as a Component of Integrated Treatment Within the Continuum of Care: Report by the Secretariat. 134th Session of the World Health Assembly. Available online: https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB134/B134_28-en.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2020).

- Emanuel, L.; Alexander, C.S.; Arnold, R.M.; Bernstein, R.; Dart, R.; Dellasantina, C.; Dykstra, L.; Tulsky, J. Integrating Palliative Care into Disease Management Guidelines. J. Palliat. Med. 2004, 7, 774–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. RACGP Aged Care Clinical Guide (Silver Book), 5th ed.; RACGP: East Melbourne, Australia, 2019; Available online: https://www.racgp.org.au/silverbook (accessed on 31 October 2020).

| Domain of Need | Considerations |

|---|---|

| Physical | Physical needs including symptom control and prevention and/or relief from medication side effects. |

| Emotional | Emotional needs including psychological assessment, understanding patient wishes for information, mood, anxiety, coping, and fears. |

| Personal | Personal needs including cultural, language, religious, or spiritual needs. |

| Social support | Social care needs of patient and carer(s). Includes practical concerns such as managing at home and at work, financial concerns, family and close relationships, social life and recreation, and concern for dependents. |

| Information communication | Information and communication needs within the health care team: between clinicians, to and from patient, and to and from carers. |

| Control and autonomy | This includes assessing mental capacity to make decisions around choice, determining the person’s preferences for treatment options, and advance care planning. |

| Out of hours and emergency | Identifying and establishing contacts for ensuring continuity of care after-hours. This includes informing patient and family of arrangements, letting after-hours GPs/locum services know of patient’s needs, and ensuring patients and carers have access to medications and equipment for when required. |

| Late care | Care considerations at the very end of life. This might include stopping non-urgent medications, communicating stage of condition to patient and family, alerting them to what might happen (e.g., rattle and agitation), providing comfort measures, and death pronouncement. |

| After care | Bereavement needs including bereavement risk assessment and follow up with the family. |

| Condition: Specific Topic (Date) | Development Organisation | Description | Length in Pages | GP Involvement in Guideline Production |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer: pain management (2013) | Australian Adult Cancer Pain Management Guideline Working Party and Cancer Council Australia | Full guideline (adapted) | NA (Online) | No |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (2018) | Lung Foundation Australia and the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand | Full guideline (update) | 210 | Yes |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (2017a) | Lung Foundation Australia and the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand | Guideline summary | 7 | Yes |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: primary care (2017b) | Lung Foundation Australia, the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand, and The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners | Guideline summary for primary care | 40 | Yes |

| * Dementia: deprescribing cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine (2018) | University of Sydney, Cognitive Decline Partnership Centre, and Bruyère Research Institute | Full guideline (new) | 132 | Yes |

| * Dementia (2016) | Cognitive Decline Partnership Centre. Guideline Adaptation Committee | Full guideline (adapted) | 136 | Yes |

| * Dementia (2016) | Cognitive Decline Partnership Centre. Guideline Adaptation Committee | Guideline summary | 6 | Yes |

| Heart failure (2018) | National Heart Foundation of Australia and Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand | Full guideline (update) | 86 | Yes |

| Heart failure (2018) | National Heart Foundation of Australia and Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand | Guideline summary | 7 | Yes |

| Guideline | Scope and Purpose (%) | Stakeholder Involvement (%) | Rigor of Development (%) | Clarity and Presentation (%) | Applicability (%) | Editorial Independence (%) | Average Score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart failure | |||||||

| Full guideline | 86.1 | 47.2 | 72.9 | 100 | 68.8 | 50.0 | 70.8 |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) | |||||||

| Full guideline | 80.6 | 88.9 | 69.8 | 88.9 | 37.5 | 100 | 77.6 |

| Dementia | |||||||

| Full guideline | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 79.2 | 100.0 | 96.5 |

| Deprescribing cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine | 97.2 | 100.0 | 96.9 | 91.7 | 88.3 | 100.0 | 95.7 |

| Cancer | |||||||

| Cancer pain management in adults | 75.0 | 75.0 | 78.0 | 97.0 | 37.5 | 61.9 | 70.7 |

| Average standardised domain score | 88.9 | 82.4 | 85.2 | 95.8 | 64.4 | 81.9 | 83.1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Damarell, R.A.; Morgan, D.D.; Tieman, J.J.; Healey, D. Bolstering General Practitioner Palliative Care: A Critical Review of Support Provided by Australian Guidelines for Life-Limiting Chronic Conditions. Healthcare 2020, 8, 553. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8040553

Damarell RA, Morgan DD, Tieman JJ, Healey D. Bolstering General Practitioner Palliative Care: A Critical Review of Support Provided by Australian Guidelines for Life-Limiting Chronic Conditions. Healthcare. 2020; 8(4):553. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8040553

Chicago/Turabian StyleDamarell, Raechel A., Deidre D. Morgan, Jennifer J. Tieman, and David Healey. 2020. "Bolstering General Practitioner Palliative Care: A Critical Review of Support Provided by Australian Guidelines for Life-Limiting Chronic Conditions" Healthcare 8, no. 4: 553. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8040553

APA StyleDamarell, R. A., Morgan, D. D., Tieman, J. J., & Healey, D. (2020). Bolstering General Practitioner Palliative Care: A Critical Review of Support Provided by Australian Guidelines for Life-Limiting Chronic Conditions. Healthcare, 8(4), 553. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8040553