Community-Based Healthcare for Migrants and Refugees: A Scoping Literature Review of Best Practices

Abstract

1. Introduction

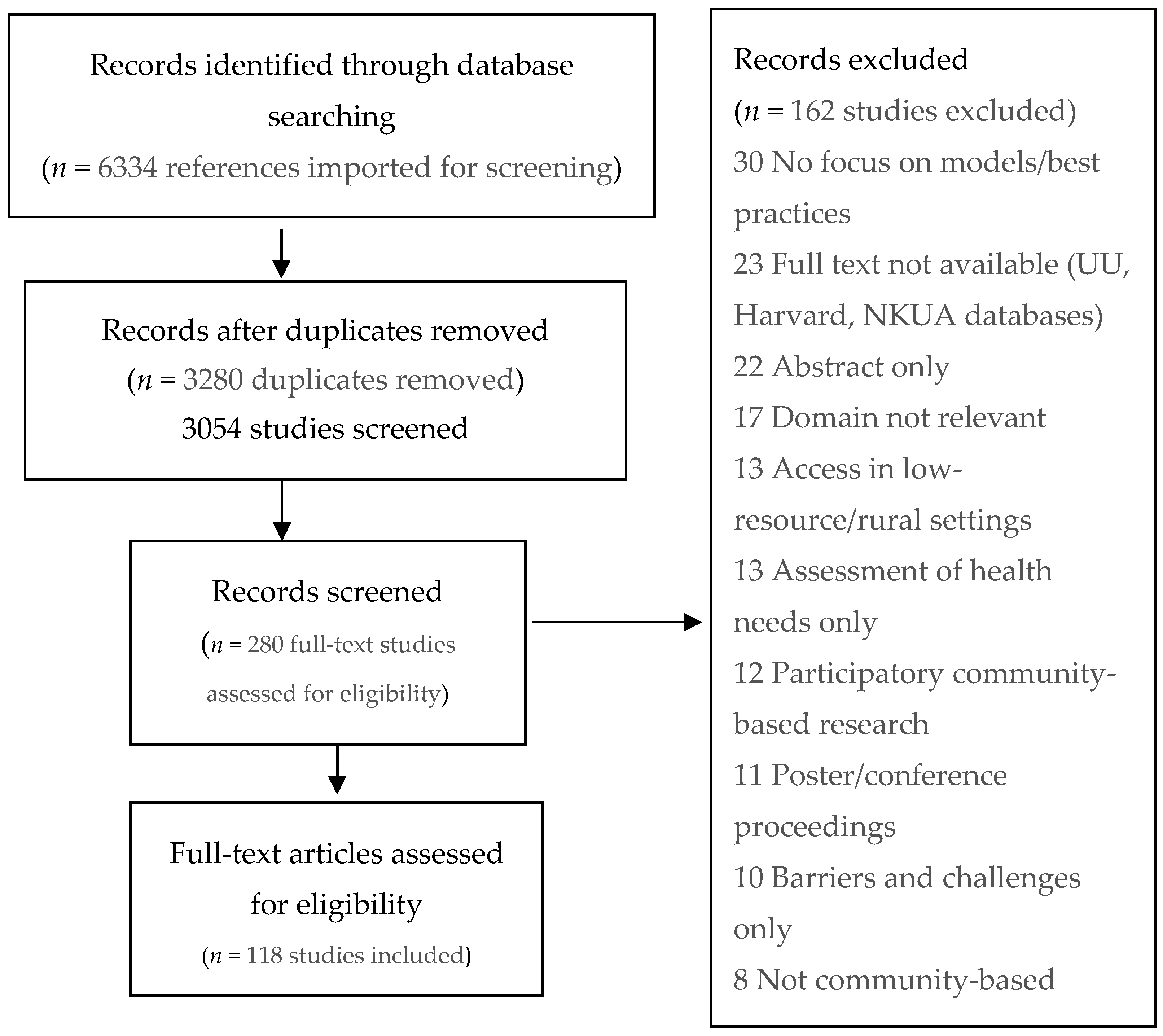

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Selection

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Data Extraction

2.3. Critical Assessment for Best Practices

3. Results

3.1. Overall Study Characteristics

3.2. Identified Best Practices According to Thematic Area of the Reviewed Records

3.2.1. Mental Health

3.2.2. Health Services

3.2.3. Noncommunicable Diseases

3.2.4. Primary Healthcare

3.2.5. Maternal, Women’s and Child Health

3.3. Promising Best Practices at the Community Level

4. Discussion

Challenges-Limitations

- This review is a comprehensive effort to identify community-based best practices at the primary healthcare level, addressing refugees and migrants in the peer-reviewed literature with the aim to provide information and guidance to the health professionals working at the primary healthcare level primarily in the EU Member States. This effort encountered several challenges/limitations. There is an abundance of publications regarding interventions for migrant/refugee healthcare in the peer-reviewed literature. A huge variation in the meaning of the terms community, community health or healthcare, and best practice was identified, along with an interchangeable use of the terms migrants and refugees, as well as immigrants, minorities, and asylum-seekers.

- The majority of publications (64.3%) originated from the US, Canada, and Australia, addressing, by large, refugees and migrants at a much-progressed social integration stage compared to Europe and from very different ethnic backgrounds.

- Many publications did not specify ethnicity; country of origin; or specific characteristics (i.e., age or social determinants) of the target population.

- Despite the richness of published information, it should be noted that multiple other interventions exist that have not (and may never) been published through a peer-review process, due to numerous reasons spanning from lower prioritization of the health issue to lack of resources to cover publications fees. Certainly, there can be areas of migrant/refugee health that could not be retrieved in the literature prior to March 2018, as no relevant publications were available. However, after reviewing some abstracts and conference proceedings, we have strong reasons to believe that many interventions delivered as pilot studies have not been published as full-text papers, despite the fact that they provide valuable insights into potentially effective community-based interventions.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR). Operational Data Portal. Available online: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/mediterranean (accessed on 17 April 2020).

- Matlin, S.A.; Depoux, A.; Schütte, S.; Flahaust, A.; Saso, L. Migrants’ and refugees’ health: Towards an agenda of solutions. Public Health Rev. 2018, 39, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Regional Office for Europe Report on the Health of Refugees and Migrants in the WHO European Region. No PUBLIC HEALTH without REFUGEE and MIGRANT HEALTH—Summary. 2018. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/311348/9789289053785-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 17 April 2020).

- WHO Regional Office for Europe. Health Promotion for Improved Refugee and Migrant Health. Copenhagen; (Technical Guidance on Refugee and Migrant Health). 2018. Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/388363/tc-health-promotion-eng.pdf?ua=1&ua=1 (accessed on 14 February 2020).

- MigHelthCare Minimize Health Inequalities and Improve the Integration of Vulnerable Migrants and Refugees into Local Communities. Available online: https://www.mighealthcare.eu/ (accessed on 26 April 2020).

- Green, L.W.; Ottoson, J.M. Community and Population Health, 8th ed.; WCB/McGraw-Hill: Boston, MA, USA, 1999; Volume 4, pp. 41–42. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, J.F.; Pinger, R.R.; Kotecki, J.E. An Introduction to Community Health; Jones and Bartlett Publishers: Boston, MA, USA, 2005; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR). Refugees and Migrants. Available online: https://refugeesmigrants.un.org/definitions (accessed on 26 April 2020).

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norris, S.L.; Rehfuess, E.A.; Smith, H.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Grimshaw, J.M.; Ford, N.P.; Portela, A. Complex health interventions in complex systems: Improving the process and methods for evidence-informed health decisions. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4, e000963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baarnhielm, S.; Edlund, A.S.; Ioannou, M.; Dahlin, M. Approaching the vulnerability of refugees: Evaluation of cross-cultural psychiatric training of staff in mental health care and refugee reception in Sweden. BMC Med. Educ. 2014, 14, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, T.; Connolly, A.M.; Klynman, N.; Majeed, A. Addressing mental health needs of asylum seekers and refugees in a London Borough: Developing a service model. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2006, 7, 249–256. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, D.E.; Overstreet, K.M.; Like, R.C.; Kristofco, R.E. Improving Depression Care for Ethnic and Racial Minorities: A Concept for an Intervention that Integrates CME Planning with Improvement Strategies. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2007, 27, S65–S74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fondacaro, K.M.; Harder, V.S. Connecting cultures: A training model promoting evidence-based psychological services for refugees. Train. Educ. Prof. Psychol. 2014, 8, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, J.M.; Isakson, B.; Githinji, A.; Roche, N.; Vadnais, K.; Parker, D.P.; Goodkind, J.R. Reducing mental health disparities through transformative learning: A social change model with refugees and students. Psychol. Serv. 2014, 11, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brar-Josan, N.; Yohani, S.C. Cultural brokers’ role in facilitating informal and formal mental health supports for refugee youth in school and community context: A Canadian case study. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2017, 47, 512–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnia, B. Refugees’ Convoy of Social Support: Community Peer Groups and Mental Health Services. Int. J. Ment. Health 2004, 32, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, H.; Rosenberg, R. Building Social Capital Through a Peer-Led Community Health Workshop: A Pilot with the Bhutanese Refugee Community. J. Community Health 2016, 41, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kieft, B.; Jordans, M.J.; de Jong, J.T.; Kamperman, A.M. Paraprofessional counselling within asylum seekers’ groups in the Netherlands: Transferring an approach for a non-western context to a European setting. Transcult. Psychiatry 2008, 45, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llosa, A.E.; Van Ommeren, M.; Kolappa, K.; Ghantous, Z.; Souza, R.; Bastin, P.; Slavuckij, A.; Grais, R.F. A two-phase approach for the identification of refugees with priority need for mental health care in Lebanon: A validation study. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, A.N.; Ornelas, I.J.; Kim, M.; Perez, G.; Green, M.; Lyn, M.J.; Corbie-Smith, G. Results from a pilot promotora program to reduce depression and stress among immigrant Latinas. Health Promot. Psychol. 2014, 15, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.-J. Effects of a Program to Improve Mental Health Literacy for Married Immigrant Women in Korea. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2017, 31, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knipscheer, J.W.; Kleber, R.J. A need for ethnic similarity in the therapist-patient interaction? Mediterranean migrants in Dutch mental-health care. J. Clin. Psychol. 2004, 60, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snowden, L.; Masland, M.; Ma, Y.; Ciemens, E. Strategies to improve minority access to public mental health services in California: Description and preliminary evaluation. J. Community Psychol. 2006, 34, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beehler, S.; Birman, D.; Campbell, R. The Effectiveness of Cultural Adjustment and Trauma Services (CATS): Generating practice-based evidence on a comprehensive, school-based mental health intervention for immigrant youth. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2012, 50, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiumento, A.; Nelki, J.; Dutton, C.; Hughes, G. School-based mental health service for refugee and asylum seeking children: Multi-agency working, lessons for good practice.Emerald Insight. J. Public Ment. Health 2011, 10, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, B.H.; Miller, A.B.; Abdi, S.; Barrett, C.; Blood, E.A.; Betancourt, T.S. Multi-tier mental health program for refugee youth. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 81, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, B.D.; Kataoka, S.; Jaycox, L.H.; Wong, M.; Fink, A.; Escudero, P.; Zaragoza, C. Theoretical basis and program design of a school-based mental health intervention for traumatized immigrant children: A collaborative research partnership. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2002, 29, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyrer, R.A.; Fazel, M. School and community-based interventions for refugee and asylum seeking children: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, L.E.; Rousseau, C. Ethnographic case study of a community day center for asylum seekers as early stage mental health intervention. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2018, 88, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gionakis, N.; Stylianidis, S. Community mental healthcare for migrants. In Social and Community Psychiatry: Towards a Critical, Patient-Oriented Approach; Stylianidis, S., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 309–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arean, P.A.; Ayalon, L.; Jin, C.; McCulloch, C.E.; Linkins, K.; Chen, H.; McDonnell-Herr, B.; Levkoff, S.; Estes, C. Integrated specialty mental health care among older minorities improves access but not outcomes: Results of the PRISMe study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2008, 23, 1086–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehn, S.D.; Jarvis, P.; Sandhra, S.K.; Bains, S.K.; Addison, M. Promoting mental health of immigrant seniors in community. Ethn. Inequalities Health Soc. Care 2014, 7, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birman, D.; Beehler, S.; Harris, E.M.; Everson, M.L.; Batia, K.; Liautaud, J.; Frazier, S.; Atkins, M.; Blanton, S.; Buwalda, J.; et al. International Family, Adult, and Child Enhancement Services (FACES): A community-based comprehensive services model for refugee children in resettlement. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2008, 78, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dura-Vila, G.; Klasen, H.; Makatini, Z.; Rahimi, Z.; Hodes, M. Mental health problems of young refugees: Duration of settlement, risk factors and community-based interventions. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2013, 18, 604–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaltman, S.; Hurtado de Mendoza, A.; Serrano, A.; Gonzales, F.A. A mental health intervention strategy for low-income, trauma-exposed Latina immigrants in primary care: A preliminary study. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2016, 86, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaltman, S.; Pauk, J.; Alter, C.L. Meeting the mental health needs of low-income immigrants in primary care: A community adaptation of an evidence-based model. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2011, 81, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, E.; Kim, Y.K.; Praetorius, R.T.; Mitschke, D.B. Mental health treatment for resettled refugees: A comparison of three approaches. Soc. Work Ment. Health 2016, 14, 342–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, S.; Divis, M.; Li, Y.B. Match or mismatch: Use of the strengths model with chinese migrants experiencing mental illness: Service user and practitioner perspectives. Am. J. Psychiatr. Rehabil. 2010, 13, 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.E.; Thompson, S.C. The use of community-based interventions in reducing morbidity from the psychological impact of conflict-related trauma among refugee populations: A systematic review of the literature. J. Immigr. Minority Health 2011, 13, 780–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, H.; Bailey, R.; Jiang, W.; Aronson, R.; Strack, R. A pilot intervention for promoting multiethnic adult refugee groups’ mental health: A descriptive article. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 2011, 9, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Shakya, Y.B.; Li, J.; Khoaja, K.; Norman, C.; Lou, W.; Abuelaish, I.; Ahmadzi, H.M. A pilot with computer-assisted psychosocial risk-assessment for refugees. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2012, 12, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polcher, K.; Calloway, S. Addressing the Need for Mental Health Screening of Newly Resettled Refugees: A Pilot Project. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2016, 7, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S.; Benbow, S.M. Mental health services for black and minority ethnic elders in the United Kingdom: A systematic review of innovative practice with service provision and policy implications. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2013, 25, 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, J.; Begley, C.; Culler, R. Evaluation of partner collaboration to improve community-based mental health services for low-income minority children and their families. Eval. Program Plan. 2014, 45, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, K.; Maxwell, C. A needs assessment in a refugee mental health project in north-east London: Extending the counselling model to community support. Med. Confl. Surviv. 2000, 16, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weine, S.M. Developing preventive mental health interventions for refugee families in resettlement. Fam. Process 2011, 50, 410–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, S. Multicultural mental health services: Projects for minority ethnic communities in England. Transcult. Psychiatry 2005, 42, 420–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khawaja, N.G.; Stein, G. Psychological Services for Asylum Seekers in the Community: Challenges and Solutions. Aust. Psychol. 2016, 51, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lee, H.B.; Hanner, J.A.; Cho, S.-J.; Han, H.-R.; Kim, M.T. Improving Access to Mental Health Services for Korean American Immigrants: Moving Toward a Community Partnership Between Religious and Mental Health Services. Psychiatry Investig. 2008, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazzal, K.H.; Forghany, M.; Geevarughese, M.C.; Mahmoodi, V.; Wong, J. An innovative community-oriented approach to prevention and early intervention with refugees in the United States. Psychol. Serv. 2014, 11, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, O.A.; Ellis, B.H.; Escudero, P.V.; Huffman-Gottschling, K.; Sander, M.A.; Birman, D. Implementing trauma interventions in schools: Addressing the immigrant and refugee experience. Adv. Educ. Divers. Communities Res. Policy Prax. 2012, 9, 95–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, G.; Guerraoui, Z.; Bonnet, S.; Gouzvinski, F.; Raynaud, J.P. Adapting services to the needs of children and families with complex migration experiences: The Toulouse University Hospital’s intercultural consultation. Transcult. Psychiatry 2017, 54, 445–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeau, L.; Measham, T. Immigrants and mental health services: Increasing collaboration with other service providers. Can. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Rev. 2005, 14, 73–76. [Google Scholar]

- Priebe, S.; Matanov, A.; Schor, R.; Straßmayr, C.; Barros, H.; Barry, M.; Díaz–Olalla, J.M.; Gabor, E.; Greacen, T.; Holcnerová, P.; et al. Good practice in mental health care for socially marginalised groups in Europe: A qualitative study of expert views in 14 countries. BMC Public Health 2012, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodkind, J.R.; Hess, J.M.; Isakson, B.; LaNoue, M.; Githinji, A.; Roche, N.; Vadnais, K.; Parker, D.P. Reducing refugee mental health disparities: A community-based intervention to address postmigration stressors with African adults. Psychol. Serv. 2014, 11, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, S. The role of a clinical director in developing an innovative assertive community treatment team targeting ethno-racial minority patients. Psychiatr. Q. 2007, 78, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeau, L.; Jaimes, A.; Johnson-Lafleur, J.; Rousseau, C. Perspectives of Migrant Youth, Parents and Clinicians on Community-Based Mental Health Services: Negotiating Safe Pathways. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2017, 26, 1936–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijbrandij, M.; Acartürk, C.; Bird, M.; Bryant, R.A.; Burchert, S.; Carswell, K.; De Jong, J.; Dinesen, C.; Dawson, K.S.; El Chammay, R.; et al. Strengthening mental health care systems for Syrian refugees in Europe and the Middle East: Integrating scalable psychological interventions in eight countries. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2017, 8, 1388102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, K.E.; Davidson, G.R.; Schweitzer, R.D. Review of refugee mental health interventions following resettlement: Best practices and recommendations. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2010, 80, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.Y.B.; Li, A.T.; Fung, K.P.; Wong, J.P. Improving Access to Mental Health Services for Racialized Immigrants, Refugees, and Non-Status People Living with HIV/AIDS. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2015, 26, 505–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, K.B.; McGregor, B.; Thandi, P.; Fresh, E.; Sheats, K.; Belton, A.; Mattox, G.; Satcher, D. Toward culturally centered integrative care for addressing mental health disparities among ethnic minorities. Psychol. Serv. 2014, 11, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, J.; Russo, A.; Block, A. The Refugee Health Nurse Liaison: A nurse led initiative to improve healthcare for asylum seekers and refugees. Contemp. Nurse 2016, 52, 710–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortinois, A.A.; Glazier, R.H.; Caidi, N.; Andrews, G.; Herbert-Copley, M.; Jadad, A.R. Toronto’s 2-1-1 healthcare services for immigrant populations. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012, 43, S475–S482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutcher, G.A.; Scott, J.C.; Arnesen, S.J. The refugee health information network: A source of multilingual and multicultural health information. J. Consum. Health Internet 2008, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, T.R.W. “Community ambassadors” for South Asian elder immigrants: Late-life acculturation and the roles of community health workers. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 1769–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, T.; Wills, J. Engaging with marginalized communities: The experiences of London health trainers. Perspect. Public Health 2011, 132, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesselink, A.E.; Verhoeff, A.P.; Stronks, K. Ethnic Health Care Advisors: A Good Strategy to Improve the Access to Health Care and Social Welfare Services for Ethnic Minorities? J. Community Health 2009, 34, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pejic, V.; Hess, R.S.; Miller, G.E.; Wille, A. Family first: Community-based supports for refugees. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2016, 86, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shommu, N.S.; Ahmed, S.; Rumana, N.; Barron, G.R.S.; McBrien, K.A.; Turin, T.C. What is the scope of improving immigrant and ethnic minority healthcare using community navigators: A systematic scoping review. Int. J. Equity Health 2016, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhagen, I.; Ros, W.J.; Steunenberg, B.; de Wit, N.J. Culturally sensitive care for elderly immigrants through ethnic community health workers: Design and development of a community based intervention programme in the Netherlands. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhagen, I.; Steunenberg, B.; de Wit, N.J.; Ros, W.J. Community health worker interventions to improve access to health care services for older adults from ethnic minorities: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ansari, W.; Newbigging, K.; Roth, C.; Malik, F. The role of advocacy and interpretation services in the delivery of quality healthcare to diverse minority communities in London, United Kingdom. Health Soc. Care Community 2009, 17, 636–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.S.; Kagawa-Singer, M. Increasing access to care for cultural and linguistic minorities: Ethnicity-specific health care organizations and infrastructure. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2007, 18, 532–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggert, L.K.; Blood-Siegfried, J.; Champagne, M.; Al-Jumaily, M.; Biederman, D.J. Coalition Building for Health: A Community Garden Pilot Project with Apartment Dwelling Refugees. J. Community Health Nurs. 2015, 32, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N.J.; Barton, J.A. A collaborative effort between a state migrant health program and a baccalaureate nursing program. J. Community Health Nurs. 1992, 9, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, A.; Rainer, L.P.; Simcox, J.B.; Thomisee, K. Increasing the delivery of health care services to migrant farm worker families through a community partnership model. Public Health Nurs. 2007, 24, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodkind, J.R.; Githinji, A.; Isakson, B. Reducing Health Disparities Experienced by Refugees Resettled in Urban Areas: A Community-Based Transdisciplinary Intervention Model. In Converging Disciplines; Kirst, M., Schaefer-McDaniel, N., Hwang, S., O’Campo, P., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, D.M.; Becker, D.M.; Bone, L.R.; Hill, M.N.; Tuggle, M.B.; Zeger, S.L. Community-academic health center partnerships for underserved minority populations. One Solut. A Natl. Crisis. JAMA 1994, 272, 309–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque, J.S.; Castañeda, H. Delivery of mobile clinic services to migrant and seasonal farmworkers: A review of practice models for community-academic partnerships. J. Community Health 2013, 38, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weissman, G.E.; Morris, R.J.; Ng, C.; Pozzessere, A.S.; Scott, K.C.; Altshuler, M.J. Global health at home: A student-run community health initiative for refugees. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2012, 23, 942–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, D.M. Caring for the Unseen: Using Linking Social Capital to Improve Healthcare Access to Irregular Migrants in Spain. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2016, 48, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner, S.M.; Liebel, D.; Wilde, M.H.; Carroll, J.K.; Zicari, E.; Chalupa, S. Meeting the Needs of Older Adult Refugee Populations With Home Health Services. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2016, 28, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afifi, R.A.; Makhoul, J.; El Hajj, T.; Nakkash, R.T. Developing a logic model for youth mental health: Participatory research with a refugee community in Beirut. Health Policy Plan. 2011, 26, 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priebe, S.; Sandhu, S.; Dias, S.F.; Gaddini, A.; Greacen, T.; Ioannidis, E.; Kluge, U.; Krasnik, A.; Lamkaddem, M.; Lorant, V.; et al. Good practice in health care for migrants: Views and experiences of care professionals in 16 European countries. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aluko, Y. Carolinas Association for Community Health Equity-CACHE: A community coalition to address health disparities in racial and ethnic minorities in Mecklenburg County North Carolina. In Eliminating Healthcare Disparities in America; Williams, R.A., Williams, R.A., Eds.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw-Taylor, Y. Culturally and linguistically appropriate health care for racial or ethnic minorities: Analysis of the US Office of Minority Health’s recommended standards. Health Policy 2002, 62, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mladovsky, P.; Ingleby, D.; McKee, M.; Rechel, B. Good practices in migrant health: The European experience. Clin. Med. 2012, 12, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tumiel-Berhalter, L.M.; Kahn, L.; Watkins, R.; Goehle, M.; Meyer, C. The implementation of Good For The Neighborhood: A participatory community health program model in four minority underserved communities. J. Community Health 2011, 36, 669–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawde, N.C.; Sivakami, M.; Babu, B.V. Building Partnership to Improve Migrants’ Access to Healthcare in Mumbai. Front. Public Health 2015, 3, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, G. Devising, implementing, and evaluating interventions to eliminate health care disparities in minority children. Pediatrics 2009, 124, S214–S223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pottie, K.; Hui, C.; Rahman, P.; Ingleby, D.; Akl, E.A.; Russell, G.; Ling, L.; Wickramage, K.; Mosca, D.; Brindis, C.D. Building Responsive Health Systems to Help Communities Affected by Migration: An International Delphi Consensus. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barenfeld, E.; Gustafsson, S.; Wallin, L.; Dahlin-Ivanoff, S. Understanding the “black box” of a health-promotion program: Keys to enable health among older persons aging in the context of migration. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2015, 10, 29013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devillé, W.; Greacen, T.; Bogić, M.; Dauvrin, M.; Dias, S.F.; Gaddini, A.; Jensen, N.K.; Karamanidou, C.; Kluge, U.; Mertaniemi, R.; et al. Health care for immigrants in Europe: Is there still consensus among country experts about principles of good practice? A Delphi study. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barenfeld, E.; Gustafsson, S.; Wallin, L.; Dahlin-Ivanoff, S. Supporting decision-making by a health promotion programme: Experiences of persons ageing in the context of migration. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2017, 12, 1337459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrera, M.J. Integrating Principles of Positive Minority Youth Development with Health Promotion to Empower the Immigrant Community: A Case Study in Chicago. J. Community Pract. 2017, 25, 504–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paoli, L. Access to health services for the refugee community in Greece: Lessons learned. Public Health 2018, 157, 104–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Health and Human Services. Refugee and Asylum Seeker Health Services- Guidelines for the Community Health Program. 2015. Available online: https://refugeehealthnetwork.org.au/refugee-and-asylum-seeker-health-services-guidelines-for-the-community-health-program (accessed on 14 February 2020).

- Philis-Tsimikas, A.; Gallo, L.C. Implementing Community-Based Diabetes Programs: The Scripps Whittier Diabetes Institute Experience. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2014, 14, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornelas, I.J.; Ho, K.; Jackson, J.C.; Moo-Young, J.; Le, A.; Do, H.H.; Lor, B.; Magarati, M.; Zhang, Y.; Taylor, V.M. Results From a Pilot Video Intervention to Increase Cervical Cancer Screening in Refugee Women. Health Educ. Behav. Off. Publ. Soc. Public Health Educ. 2018, 45, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Jandu, B.; Albagli, A.; Angus, J.E.; Ginsburg, O. Exploring ways to overcome barriers to mammography uptake and retention among South Asian immigrant women. Health Soc. Care Community 2013, 21, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J. Development and pilot test of pictograph-enhanced breast health-care instructions for community-residing immigrant women. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2012, 18, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escribà-Agüir, V.; Rodríguez-Gómez, M.; Ruiz-Pérez, I. Effectiveness of patient-targeted interventions to promote cancer screening among ethnic minorities: A systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol. 2016, 44, 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirazi, M.; Shirazi, A.; Bloom, J. Developing a culturally competent faith-based framework to promote breast cancer screening among Afghan immigrant women. J. Relig. Health 2015, 54, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzubaidi, H.; Mc Namara, K.; Browning, C. Time to question diabetes self-management support for Arabic-speaking migrants: Exploring a new model of care. Diabet. Med. A J. Br. Diabet. Assoc. 2017, 34, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, K.N.; Mclean, Y.; Byers, S.; Taylor, H.; Braizat, O.M. Combined Diabetes Prevention and Disease Self-Management Intervention for Nicaraguan Ethnic Minorities: A Pilot Study. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. Res. Educ. Action 2017, 11, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wieland, M.L.; Njeru, J.W.; Hanza, M.M.; Boehm, D.; Singh, D.; Yawn, B.P.; Patten, C.A.; Clark, M.M.; Weis, J.A.; Osman, A.; et al. Stories for change: Pilot feasibility project of a diabetes digital storytelling intervention for refugee and immigrant adults with type 2 diabetes. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2017, 32, S319. [Google Scholar]

- Zeh, P.; Sandhu, H.K.; Cannaby, A.M.; Sturt, J.A. The impact of culturally competent diabetes care interventions for improving diabetes-related outcomes in ethnic minority groups: A systematic review. Diabet. Med. A J. Br. Diabet. Assoc. 2012, 29, 1237–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, A.; Musshauser, D.; Sahin, F.; Bezirkan, H.; Hochleitner, M. The Mosque Campaign: A cardiovascular prevention program for female Turkish immigrants. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2006, 118, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Vijver, S.; Oti, S.O.; Van Charante, E.P.M.; Allender, S.; Foster, C.; Lange, J.; Oldenburg, B.; Kyobutungi, C.; Agyemang, C. Cardiovascular prevention model from Kenyan slums to migrants in the Netherlands. Glob. Health 2015, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, S.; Jonsson, R.; Skaff, R.; Tyler, F. Community-Based Noncommunicable Disease Care for Syrian Refugees in Lebanon. Glob. Health Sci. Pract. 2017, 5, 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddaiah, R.; Roberts, J.E.; Graham, L.; Little, A.; Feuerman, M.; Cataletto, M.B. Community health screenings can complement public health outreach to minority immigrant communities. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. Res. Educ. Action 2014, 8, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, I.-H.; Wahidi, S.; Vasi, S.; Samuel, S. Importance of community engagement in primary health care: The case of Afghan refugees. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2015, 21, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin-Zamir, D.; Keret, S.; Yaakovson, O.; Lev, B.; Kay, C.; Verber, G.; Lieberman, N. Refuah Shlema: A cross-cultural programme for promoting communication and health among Ethiopian immigrants in the primary health care setting in Israel: Evidence and lessons learned from over a decade of implementation. Glob. Health Promot. 2011, 18, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, R. Primary health care for refugees and asylum seekers: A review of the literature and a framework for services. Public Health 2006, 120, 809–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMurray, J.; Breward, K.; Breward, M.; Alder, R.; Arya, N. Integrated primary care improves access to healthcare for newly arrived refugees in Canada. J. Immigr. Minority Health 2014, 16, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, C.; Hall, S.; Elmitt, N.; Bookallil, M.; Douglas, K. People-centred integration in a refugee primary care service: A complex adaptive systems perspective. J. Ournal Integr. Care 2017, 25, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottie, K.; Batista, R.; Mayhew, M.; Mota, L.; Grant, K. Improving delivery of primary care for vulnerable migrants: Delphi consensus to prioritize innovative practice strategies. Can. Fam. Physician 2014, 60, e32–e40. [Google Scholar]

- Griswold, K.S.; Pottie, K.; Kim, I.; Kim, W.; Lin, L. Strengthening effective preventive services for refugee populations: Toward communities of solution. Public Health Rev. 2018, 39, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElmurry, B.J.; Park, C.G.; Buseh, A.G. The nurse-community health advocate team for urban immigrant primary health care. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. Off. Publ. Sigma Theta Tau Int. Honor Soc. Nurs. 2003, 35, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Cho, H.-I.; Cheon-Klessig, Y.S.; Gerace, L.M.; Camilleri, D.D. Primary health care for Korean immigrants: Sustaining a culturally sensitive model. Public Health Nurs. 2002, 19, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelland, J.; Riggs, E.; Szwarc, J.; Casey, S.; Dawson, W.; Vanpraag, D.; East, C.; Wallace, E.; Teale, G.; Harrison, B.; et al. Bridging the Gap: Using an interrupted time series design to evaluate systems reform addressing refugee maternal and child health inequalities. Implement. Sci. 2015, 10, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchins, V.; Walch, C. Meeting minority health needs through special MCH projects. Public Health Rep. 1989, 104, 621–626. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bhagat, R.; Johnson, J.; Grewal, S.; Pandher, P.; Quong, E.; Triolet, K. Mobilizing the community to address the prenatal health needs of Immigrant Punjabi women. Public Health Nurs. 2002, 19, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, S.; Camacho, D.; Freund, K.M.; Bigby, J.; Walcott-McQuigg, J.; Hughes, E.; Nunez, A.; Dillard, W.; Weiner, C.; Weitz, T.; et al. Women’s health centers and minority women: Addressing barriers to care. The National Centers of Excellence in Women’s Health. J. Women’s Health Gend. Based Med. 2001, 10, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikh, M.; MacIntyre, C.R. The impact of intensive health promotion to a targeted refugee population on utilisation of a new refugee paediatric clinic at the children’s hospital at Westmead. Ethn. Health 2009, 14, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reavy, K.; Hobbs, J.; Hereford, M.; Crosby, K. A new clinic model for refugee health care: Adaptation of cultural safety. Rural Remote Health 2012, 12, 1826. [Google Scholar]

- Krause, S.; Williams, H.A.; Onyango, M.A.; Sami, S.; Doedens, W.; Giga, N.; Stone, E.; Tomczyk, B. Reproductive health services for Syrian refugees in Zaatri Camp and Irbid City, Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan: An evaluation of the Minimum Initial Services Package. Confl. Health 2015, 9, S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E (accessed on 15 April 2020).

| Study Design | Sample Size (n) | Duration of Follow-Up | Middle Eastern/North African Individuals Included in Target Population | Reported Outcomes/Or Advocate Evidence-Backed Approach | Reproducible (As Mentioned in Publication) | Theoretical Underpinning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 = not specified | NA = not applicable | NA = not applicable | 1 = no | 1 = no | 1 = not mentioned | NA = not applicable |

| 1 = review/description (no data) | 1 = <10 | C = cross-sectional design | 2 = yes | 2 = yes | 2 = can be reproduced | 1 = not present in publication |

| 2 = qualitative or quantitative data | 2 = 11–50 | 1 = days | 2 = presented in publication | |||

| 3 = mixed methods | 3 = 51–100 | 2 = weeks | ||||

| 4 = experimental study (randomized, controlled, or pre-post-test design) | 4 = > 100 or ≤ 10 papers (for reviews) | 3 = months | ||||

| 5 = literature review | 5 = > 1000 or > 10 papers (for reviews) | 4 = 1–5 years | ||||

| P = pilot study | 5 = > 5 years |

| Publication | Reference Number | Area of Intervention | Intervention | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| McMurray (2014) | [116] | Primary healthcare | Partnership between a dedicated health clinic for government-assisted refugees, a local reception center, and community providers | 20 |

| Reavy (2012) | [127] | Maternal health | New clinic model for prenatal and pediatric refugee patients (in particular, the role of the Culturally Appropriate Resources and Education (C.A.R.E.) Clinic Health Advisor) | 19 |

| Small (2016) | [38] | Mental health | Comparison of three different treatment modalities: treatment as usual (TAU), home-based counseling (HBC), and a community-based psycho-educational group (CPG) | 18 |

| Bader (2006) | [109] | Noncommunicable Diseases | Linguistically and culturally sensitive cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention program | 17 |

| Sheikh & McIntyre (2002) | [126] | Maternal health | Intensive child health promotion and education campaign using ethnic media and social network | 17 |

| Williams & Thompson (2011) | [40] | Mental health | Community-based mental healthcare services | 17 |

| Kaltman (2011) | [37] | Mental health | Collaborative mental healthcare program implemented in a network of primary care clinics that serve the uninsured | 17 |

| Fondacarro (2016) | [14] | Mental health | Training program for psychology students (“Connecting Cultures”) | 16 |

| Levin-Zamir (2011) | [114] | Primary healthcare | Cross-cultural program for promoting communication and health | 15 |

| Siddaiah (2014) | [112] | Noncommunicable Diseases | Community-based, culturally competent respiratory health screening and education | 15 |

| Tumiel-Behalter (2011) | [89] | Health service provision | Community program with a participatory approach to improve the health of four underserved communities (“Good For The Neighborhood”) | 15 |

| Ferrera (2017) | [96] | Health service provision | Health promotion initiative that integrates principles of positive minority youth development | 15 |

| Tyrer & Fazel (2014) | [29] | Mental health | School and community-based interventions | 15 |

| Kaltman (2016) | [36] | Mental health | Mental health intervention for primary care clinics that serve the uninsured | 15 |

| Goodkind (2014) | [56] | Mental health | Community-based advocacy and learning intervention with refugees and undergraduate students | 15 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Riza, E.; Kalkman, S.; Coritsidis, A.; Koubardas, S.; Vassiliu, S.; Lazarou, D.; Karnaki, P.; Zota, D.; Kantzanou, M.; Psaltopoulou, T.; et al. Community-Based Healthcare for Migrants and Refugees: A Scoping Literature Review of Best Practices. Healthcare 2020, 8, 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8020115

Riza E, Kalkman S, Coritsidis A, Koubardas S, Vassiliu S, Lazarou D, Karnaki P, Zota D, Kantzanou M, Psaltopoulou T, et al. Community-Based Healthcare for Migrants and Refugees: A Scoping Literature Review of Best Practices. Healthcare. 2020; 8(2):115. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8020115

Chicago/Turabian StyleRiza, Elena, Shona Kalkman, Alexandra Coritsidis, Sotirios Koubardas, Sofia Vassiliu, Despoina Lazarou, Panagiota Karnaki, Dina Zota, Maria Kantzanou, Theodora Psaltopoulou, and et al. 2020. "Community-Based Healthcare for Migrants and Refugees: A Scoping Literature Review of Best Practices" Healthcare 8, no. 2: 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8020115

APA StyleRiza, E., Kalkman, S., Coritsidis, A., Koubardas, S., Vassiliu, S., Lazarou, D., Karnaki, P., Zota, D., Kantzanou, M., Psaltopoulou, T., & Linos, A. (2020). Community-Based Healthcare for Migrants and Refugees: A Scoping Literature Review of Best Practices. Healthcare, 8(2), 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8020115