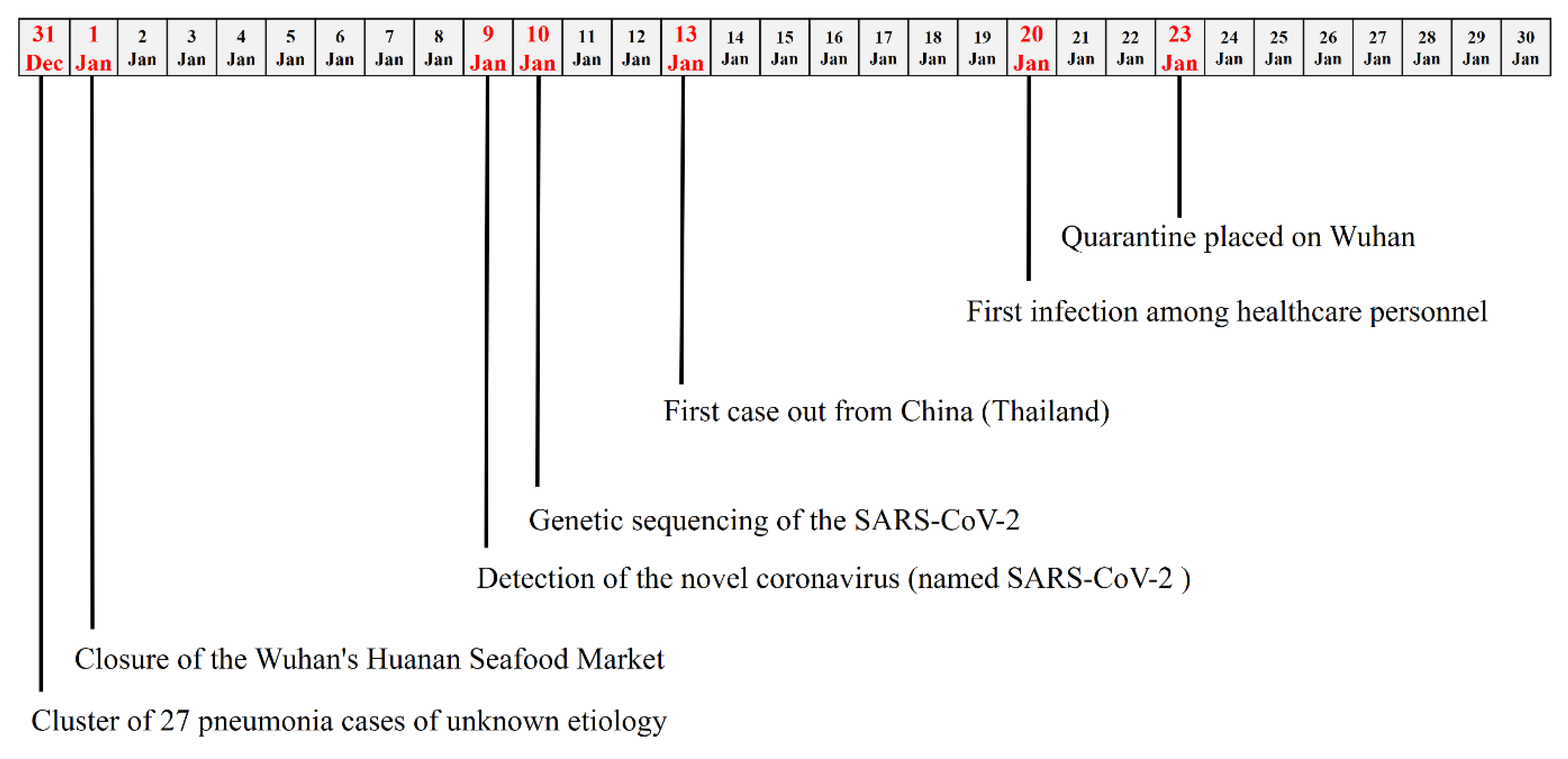

On 31 December, 2019, a cluster of 27 pneumonia cases of unknown etiology was reported by Chinese health authorities in Wuhan City (China). In particular, for almost all cases, an exposition to the Wuhan’s Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market was found and, thus, the market was considered the most probable source of the virus outbreak [1]. Chinese health authorities have taken prompt public health measures, including intensive surveillance, epidemiological investigations, and closure of the market on 1 January, 2020 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Timeline of the key events observed in the first month of the 2019 severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) outbreak.

On 9 January, 2020, the Chinese Government reported that the cause of the outbreak was a novel coronavirus, recently named SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2) [2], and was responsible for a disease defined COVID-19 (novel coronavirus disease 2019). This virus has been detected as the causative agent for 15 of the 59 pneumonia cases [3].

From that date, an increasing number of studies have been published and several international institutions (World Health Organization, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, European Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) have provided findings supporting a rapid increase in the general knowledge. However, despite these significant improved data, many questions about the new coronavirus remain, and answers could be strategic for programming and designing public health interventions.

SARS-CoV-2 was found to be a β-Coronavirus of group 2B with at least 70% similarity in genetic sequence to SARS-CoV-1, but sufficiently divergent to be considered a new human-infecting betacoronavirus (Table 1) [4]. It is highly probable that genome differences between SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 could be responsible for the different functionality and pathogenesis; thus, further studies could significantly help to solve this gap. The genetic sequence of the SARS-CoV-2 has been shared on 10 January, 2020, in order to allow the production of specific diagnostic PCR tests in different countries for detecting the novel infection [5].

Table 1.

Summary of the scientific evidences, suggestions, and pending questions on the 2019 SARS-CoV-2 outbreak.

The evident convergence between SARS-CoV-2 and bat coronavirus (at least 96% identical at the whole-genome level) seems to suggest that bats could be the original host [6]. A possible role of civets, snakes, and pangolins is not excluded as potential intermediate hosts, and it is clear that tracking the path of the virus could be crucial for preventing further exposure and outbreaks in the future.

The SARS-CoV-2 RNA sequences have been found to have limited variability and the estimated mutation rates in coronavirus, which SARS-CoV-2 phylogenetically links to, are moderate to high, compared to the others in the category of single-stranded RNA viruses [7]. However, an accurate measure of the mutation rate for SARS-CoV-2 has not been calculated and the evaluation of its genetic evolution over time could have important implications for strategic planning in the prevention, as well as in the development of vaccines and antibodies-based therapies.

Another important key point is the role of humoral immunity that, as for other coronavirus, might not be strong or long-lasting enough to keep patients safe from contracting the disease again.

After infection occurred, incubation has been estimated to vary from 5 to 6 days, with a range of up to 14 days [8]. However, the knowledge of the true incubation time could improve the estimates of the rates of asymptomatic and subclinical infections among immunocompetent individuals; thus, increasing the specificity in detecting COVID-19 cases. Additionally, it could significantly change the forecasting projection models on the worldwide outbreak evolution.

In this sense, recently published studies have estimated a basic reproductive number of 3.28, exceeding the initial World Health Organization (WHO) estimates of 1.4 to 2.5 [9]. The basic reproductive number is an indication of viral transmissibility, representing the average number of new infections generated by a single infectious person in a totally naïve population; thus, when it decreases below 1, the outbreak can be considered under control. Moreover, there are evidences that SARS-CoV-2 appears to have been transmitted during the incubation period of patients in whom the illness was brief and nonspecific, whereas the detection of SARS-CoV-2 with a high viral load in the sputum of convalescent patients arouse concern about prolonged shedding of the virus after recovery [10].

In symptomatic COVID-19 patients, illness may evolve over the course of a week or longer, beginning with mild symptoms that progress (in some cases) to the point of dyspnea and shock [11]. Most common complaints are fever (almost universal), cough, which may or may not be productive, whereas myalgia and fatigue are relatively common conditions [12].

The updated case fatality rate of diagnosed cases is 2.3%, with an increasing risk in subjects aged 60 and older (3.6% in subjects 60–69 years old; 8% in subjects 70–79 years old; and 14.8% in subjects aged 80 and older), and those with comorbidities (case fatality rate in healthy subjects was 0.9%) [13]. Moreover, fatality rates seem to be decreasing over time (15.6%, 1–10 January, 2020; 5.7%, 11–20 January, 2020; 1.9%, 21–31 January, 2020; 0.8% after 1 February, 2020) although this finding could be due to the increasing detection of “mild” cases in the general population or to a better management of the disease [14].

Unfortunately, to date, there are no vaccines against SARS-CoV-2, and there is the awareness that several months may be required to undergo extensive testing, and determine vaccine safety and efficacy before a potential wide use. Similarly, there is no single specific antiviral therapy; COVID-19 and the main treatments are supportive care (e.g., supportive therapy and monitoring—oxygen therapy and fluid management). In the last days, recombinant interferon (IFN) with ribavirin and infusions of blood plasma from people who have recovered from the COVID-19 are under evaluation, to treat infected subjects with encouraging results [14].

In conclusion, it is evident that in just a few weeks, the international scientific community has been involved in producing well-documented evidences in order to increase general knowledge about epidemiology, immunopathology, prevention, and treatment of COVID-19. However, many doubts about the new coronavirus remain, whereas there is the conviction that finding and sharing answers to these questions could represent a major challenge for public health control of a possible global SARS-CoV-2 outbreak.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.A., F.V. and F.T.; methodology, E.A. and A.C.; resources, E.A. and L.C.; data curation, E.A. and L.C.; writing—original draft preparation, E.A., A.C., L.C., F.V. and F.T.; writing—review and editing, E.A., A.C., L.C., F.V. and F.T.; supervision, F.V. and A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wuhan Municipal Health and Health Commission’s Briefing on the Current Pneumonia Epidemic Situation in Our City. 2019. Available online: http://wjw.wuhan.gov.cn/front/web/showDetail/2019123108989 (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Naming the Coronavirus Disease (World Health Organization). Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/naming-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-2019)-and-the-virus-that-causes-it (accessed on 24 February 2020).

- Chinese Position on Novel 2019 Coronavirus. Available online: http://www.xinhuanet.com/2020-01/09/c_1125438971.htm (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Wu, A.; Peng, Y.; Huang, B.; Ding, X.; Wang, X.; Niu, P.; Meng, J.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; et al. Genome Composition and Divergence of the Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Originating in China. Cell Host Microbe 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Event Background (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control). Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/novel-coronavirus/event-background-2019 (accessed on 18 February 2020).

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.L.; Wang, X.G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Si, H.R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.L.; et al. Pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Li, H.; Wu, X.; Zhong, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, Y.P.; Boerwinkle, E.; Fu, Y.X. Moderate mutation rate in the SARS coronavirus genome and its implications. BMC Evol Biol. 2004, 28, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Risk Assessment (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control). Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/SARS-CoV-2-risk-assessment-14-february-2020.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2020).

- Liu, Y.; Gayle, A.A.; Wilder-Smith, A.; Rocklöv, J. The reproductive number of COVID-19 is higher compared to SARS coronavirus. J. Travel Med. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothe, C.; Schunk, M.; Sothmann, P.; Bretzel, G.; Froeschl, G.; Wallrauch, C.; Zimmer, T.; Thiel, V.; Janke, C.; Guggemos, W.; et al. Transmission of 2019-nCoV Infection from an Asymptomatic Contact in Germany. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 15, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Zhou, M.; Dong, X.; Qu, J.; Gong, F.; Han, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Wei, Y.; et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A descriptive study. Lancet 2020, 15, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weekly Surveillance (Chinese Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Available online: http://weekly.chinacdc.cn/en/article/id/e53946e2-c6c4-41e9-9a9b-fea8db1a8f51 (accessed on 20 February 2020).

- Cinatl, J.; Morgenstern, B.; Bauer, G.; Chandra, P.; Rabenau, H.; Doerr, H. Treatment of SARS with human interferons. Lancet 2003, 362, 293–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Interim Guidance for Environmental Cleaning in Nonhealthcare Facilities Exposed to 2019-nCoV (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control). Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/novel-coronavirus-guidance-environmental-cleaning-non-healthcare-facilities.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2020).

- Kock, R.A.; Karesh, W.B.; Veas, F.; Velavan, T.P.; Simons, D.; Mboera, L.E.G.; Dar, O.; Arruda, L.B.; Zumla, A. 2019-nCoV in context: lessons learned? Lancet Planet Health 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampf, G.; Todt, D.; Pfaender, S.; Steinmann, E. Persistence of coronaviruses on inanimate surfaces and its inactivation with biocidal agents. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- How COVID-19 Spreads (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/about/transmission.html (accessed on 24 February 2020).

- Advice for Public (World Health Organization). Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public (accessed on 22 February 2020).

- Backer, J.A.; Klinkenberg, D.; Wallinga, J. Incubation period of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infections among travellers from Wuhan, China, 20–28 January 2020. Euro. Surveill. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, R.L.; Donaldson, E.F.; Baric, R.S. A decade after SARS: strategies for controlling emerging coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 836–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).