Ageing and Quality of Life in Older Adults: Updates and Perspectives of Psychosocial and Advanced Technological Interventions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Rationale and Objectives

3. Ageing, Older Adults, and Multimorbidity

4. Older Adults, Health/Welfare Services, and Institutionalisation

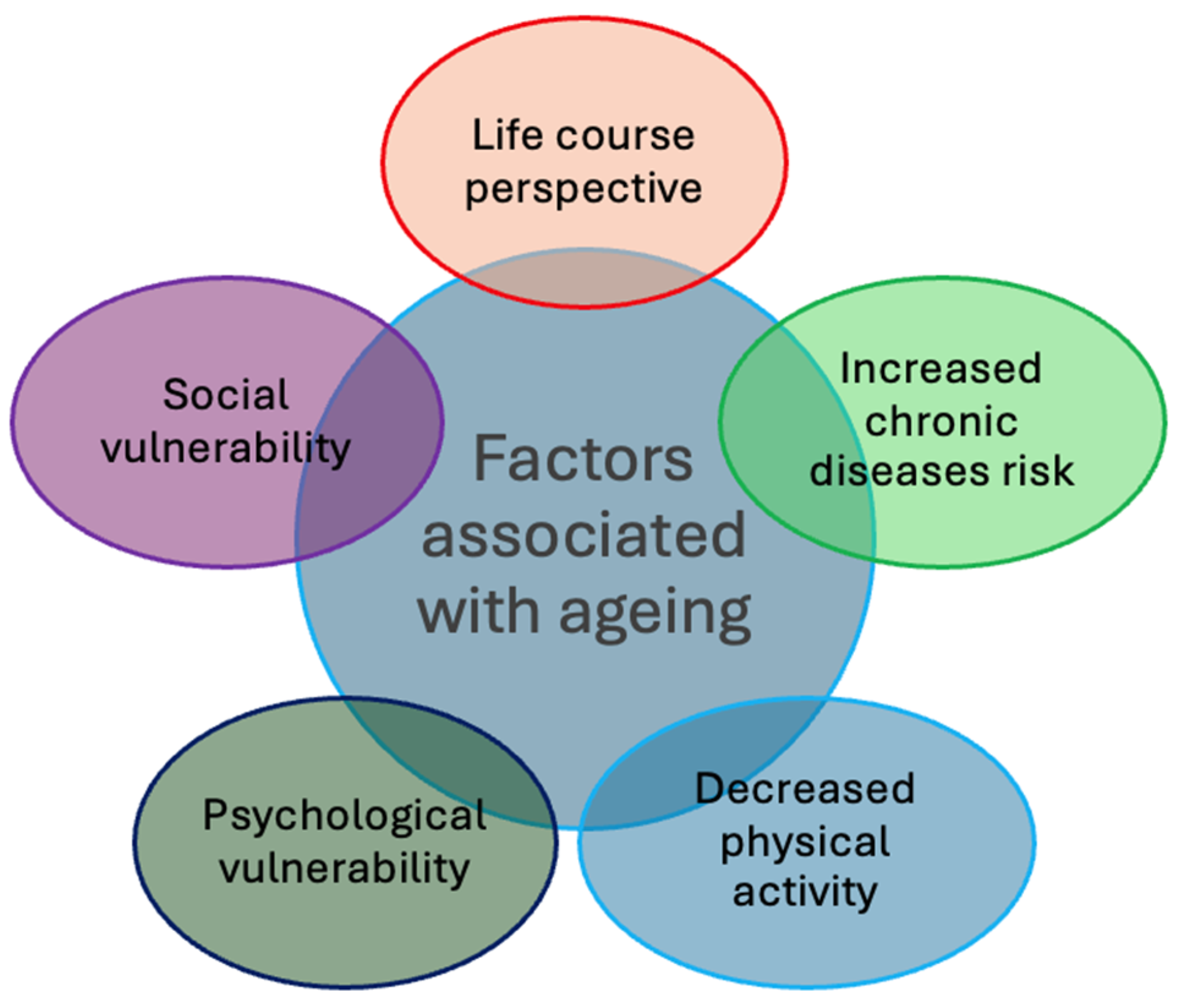

5. Bio-Psycho-Social Determinants of Ageing

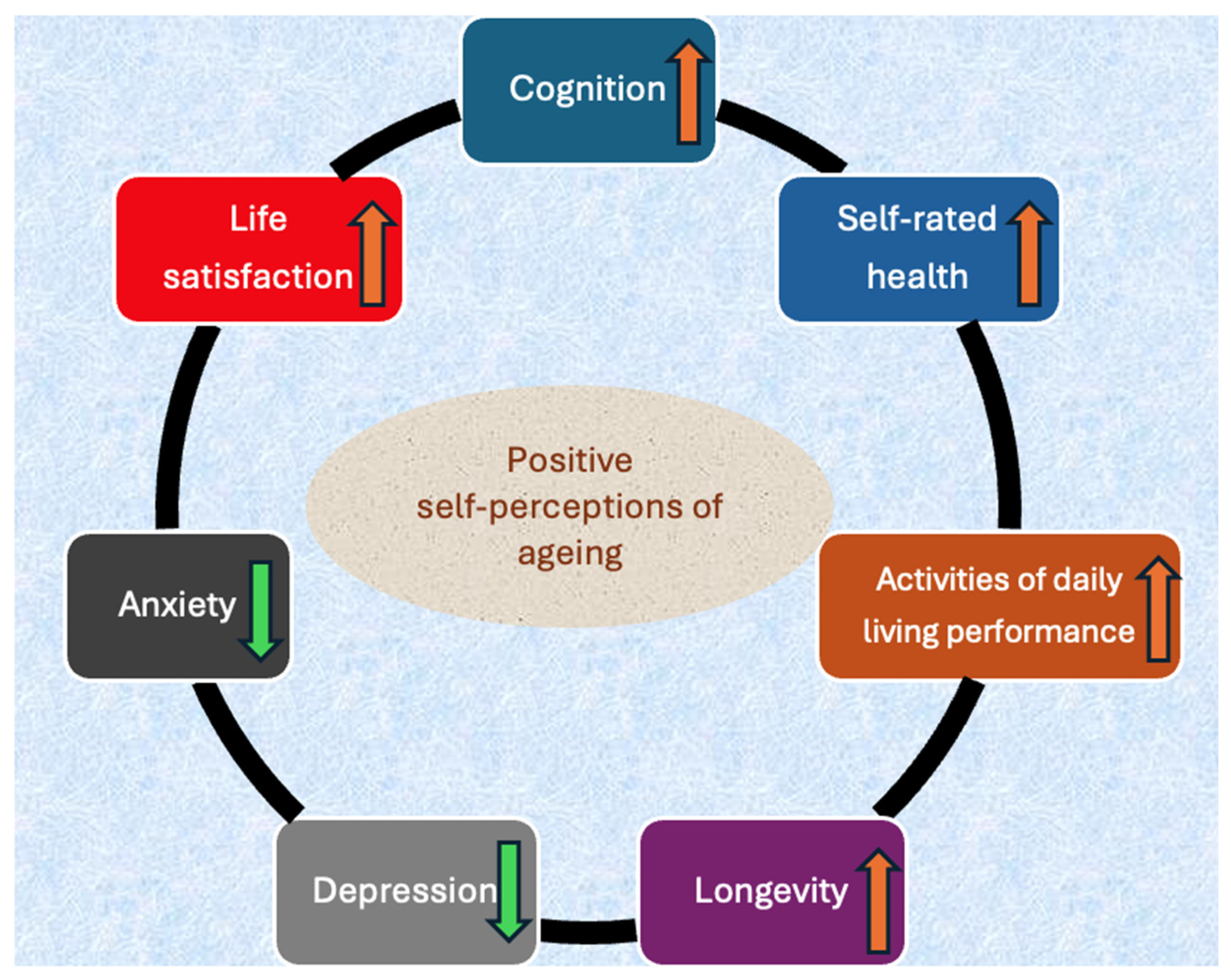

6. Active Ageing, Successful Ageing, and Cognitive Ageing

7. Older Population and COVID-19

8. Quality of Life Among Older Adults

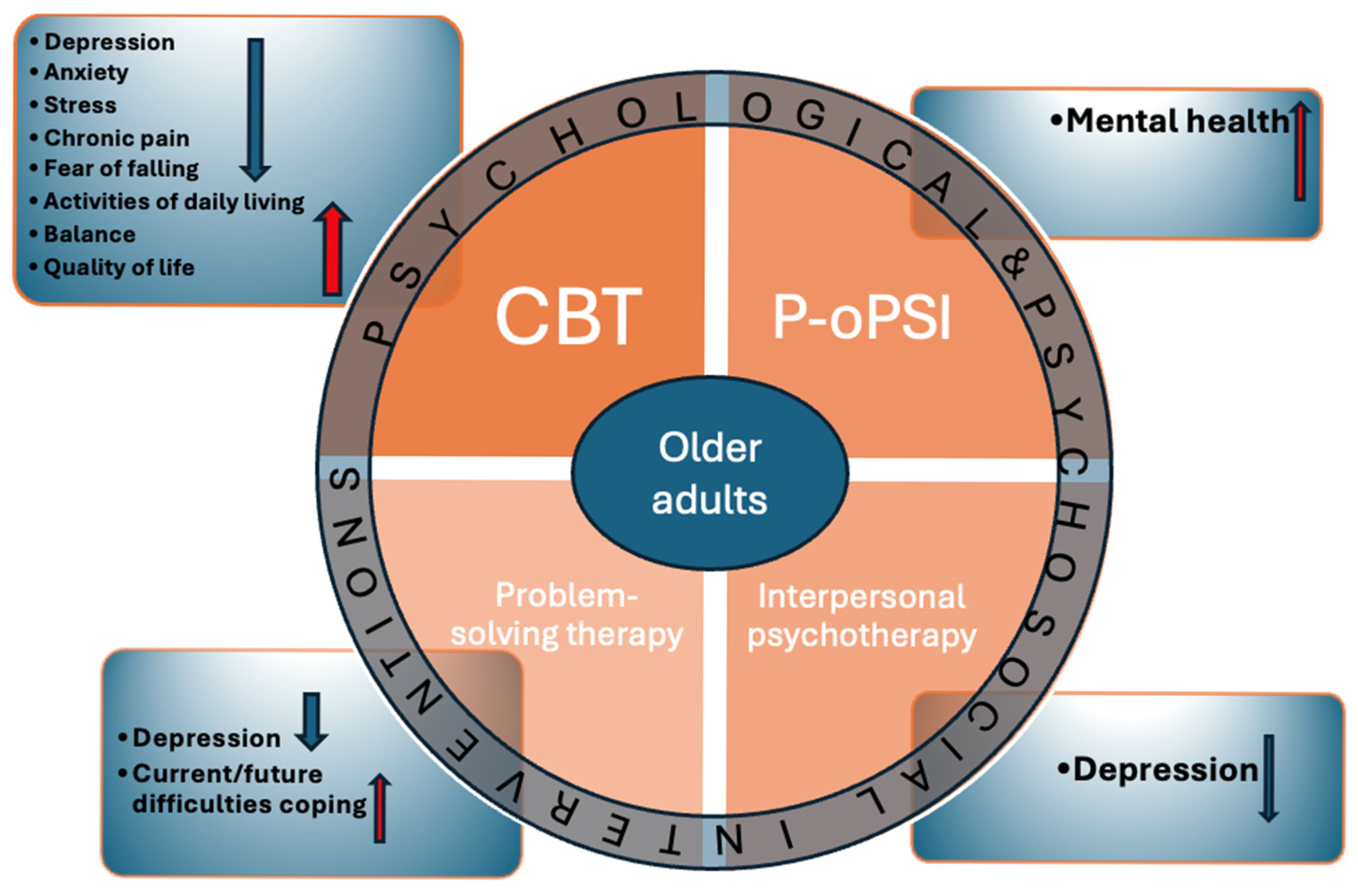

9. Psychosocial Interventions

10. The Role of Advanced Technology

11. Conclusions, Challenges, and Future Considerations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- de Medeiros, M.M.D.; Carletti, T.M.; Magno, M.B.; Maia, L.C.; Cavalcanti, Y.W.; Rodrigues-Garcia, R.C.M. Does the institutionalization influence elderly’s quality of life? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2019 Ageing Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of diseases and injuries for adults 70 years and older: Systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease 2019 Study. BMJ 2022, 376, e068208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Ageing and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Ferrucci, L.; Giallauria, F.; Guralnik, J.M. Epidemiology of ageing. Radiol. Clin. N. Am. 2008, 46, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asian Development Bank. Adapting to Ageing Asia and the Pacific. Available online: https://www.adb.org/what-we-do/topics/social-development/aging-asia (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Population Reference Bureau. Fact Sheet: Ageing in the United States. Available online: www.prb.org/resources/fact-sheet-aging-in-the-united-states (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- United Nations. Political Declaration and Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing. In Proceedings of the Second World Assembly on Ageing, Madrid, Spain, 8–12 April 2002; Available online: https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/documents/ageing/MIPAA/political-declaration-en.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Pruchno, R. Technology and Ageing: An Evolving Partnership. Gerontologist 2019, 59, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czaja, S.J. Current Findings and Issues in Technology and Aging. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2021, 40, 463–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengoni, A.; Angleman, S.; Melis, R.; Mangialasche, F.; Karp, A.; Garmen, A.; Meinow, B.; Fratiglioni, L. Ageing with multimorbidity: A systematic review of the literature. Ageing Res. Rev. 2011, 10, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, E.; Zoli, M.; Gonzalez-Freire, M.; Salive, M.E.; Studenski, S.A.; Ferrucci, L. Ageing and Multimorbidity: New Tasks, Priorities, and Frontiers for Integrated Gerontological and Clinical Research. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2015, 16, 640–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drazen, J.M.; Fabbri, L.M. Ageing and multimorbidity. Eur. Respir. J. 2014, 44, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makovski, T.T.; Schmitz, S.; Zeegers, M.P.; Stranges, S.; van den Akker, M. Multimorbidity and quality of life: Systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2019, 53, 100903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salive, M.E. Multimorbidity in older adults. Epidemiol. Rev. 2013, 35, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, K.; Liu, W.; Fitzpatrick, D.; Hardacre, K.A.; Roberts, S.; Salerno, J.; Stranges, S.; Fortin, M.; Mangin, D. Prevalence of multimorbidity and polypharmacy among adults and older adults: A systematic review. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2024, 5, e287–e296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, K.H.; Hsu, C.C.; Yu, P.C.; Liu, H.Y.; Chen, Z.J.; Chen, Y.W.; Peng, L.N.; Lin, M.H.; Chen, L.K. Determinants of improved quality of life among older adults with multimorbidity receiving integrated outpatient services: A hospital-based retrospective cohort study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2021, 97, 104475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, Y.T.; Chen, M.H.; Lu, T.H.; Yang, Y.P.; Chang, C.M.; Yang, Y.C. Effects of an integrated ambulatory care program on healthcare utilization and costs in older patients with multimorbidity: A propensity score-matched cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xi, J.Y.; Liang, B.H.; Zhang, W.J.; Yan, B.; Dong, H.; Chen, Y.Y.; Lin, X.; Gu, J.; Hao, Y.T. Effects of population ageing on quality of life and disease burden: A population-based study. Glob. Health Res. Policy 2025, 10, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, L.P.; Vissoci, J.R.N.; França, D.G.; Caruzzo, N.M.; Batista, S.R.R.; de Oliveira, C.; Nunes, B.P.; Silveira, E.A. Multimorbidity patterns and hospitalisation occurrence in adults and older adults aged 50 years or over. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, L.P.; de Oliveira Rezende, A.T.; Delpino, F.M.; Mendonça, C.R.; Noll, M.; Nunes, B.P.; de Oliviera, C.; Silveira, E.A. Association between multimorbidity and hospitalization in older adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 2022, 51, afac155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.X.; Walsh, E.I.; Sutarsa, I.N. Provision of health services for elderly populations in rural and remote areas in Australia: A systematic scoping review. Aust. J. Rural Health 2023, 31, 805–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luppa, M.; Luck, T.; Weyerer, S.; König, H.H.; Brähler, E.; Riedel-Heller, S.G. Prediction of institutionalization in the elderly. A systematic review. Age Ageing 2010, 39, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fealy, S.; McLaren, S.; Nott, M.; Seaman, C.E.; Cash, B.; Rose, L. Psychological interventions designed to reduce relocation stress for older people transitioning into permanent residential aged care: A systematic scoping review. Aging Ment. Health 2024, 28, 1197–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaosar, G.M.A.A.; Hoque, M.R.; Bao, Y. Investigating Factors Affecting Elderly’s Intention to Use m-Health Services: An Empirical Study. Telemed. J. E Health 2018, 24, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Kalun, O.C. Acceptance of mHealth by Elderly Adults: A Path Analysis. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, Virtual, 5–9 October 2020; Volume 64, pp. 755–759. [Google Scholar]

- Bambeni, N. Perspective Chapter: Social Ageing Challenges Faced by Older Adults Exposed to Conditions of Underdevelopment and Extreme Poverty; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2024; Available online: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/84565 (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- Illario, M.; De Luca, V.; Onorato, G.; Tramontano, G.; Carriazo, A.M.; Roller-Wirnsberger, R.E.; Apostolo, J.; Eklund, P.; Goswami, N.; Iaccarino, G.; et al. Interactions Between EIP on AHA Reference Sites and Action Groups to Foster Digital Innovation of Health and Care in European Regions. Clin. Interv. Aging 2022, 17, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dziechciaż, M.; Filip, R. Biological psychological and social determinants of old age: Bio-psycho-social aspects of human aging. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2014, 21, 835–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutledge, J.; Oh, H.; Wyss-Coray, T. Measuring biological age using omics data. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2022, 23, 715–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gellert, P.; Alonso-Perez, E. Psychosocial and biological pathways to ageing: The role(s) of the behavioral and social sciences in geroscience. Z. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2024, 57, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, S.T.; Carstensen, L.L. Social and emotional aging. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2010, 61, 383–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steptoe, A.; Deaton, A.; Stone, A.A. Subjective wellbeing, health, and ageing. Lancet 2015, 385, 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, H.; Kim, H. Ageism and Psychological Wellbeing Among Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2022, 8, 23337214221087023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wernher, I.; Lipsky, M.S. Psychological theories of aging. Dis. Mon. 2015, 61, 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, B. Stereotype Embodiment: A Psychosocial Approach to Ageing. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 18, 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Active Ageing: A Policy Framework. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/67215/WHO_NMH_NPH_02.8.pdf?sequence=1andisAllowe (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Ayoubi-Mahani, S.; Eghbali-Babadi, M.; Farajzadegan, Z.; Keshvari, M.; Farokhzadian, J. Active aging needs from the perspectives of older adults and geriatric experts: A qualitative study. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1121761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, J.W.; Kahn, R.L. Successful aging. Gerontologist 1997, 37, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; D’Arcy, C. Successful aging in Canada: Prevalence and predictors from a population-based sample of older adults. Gerontology 2014, 60, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.N.; Choi, Y.J.; Kim, D.H. Association of socioeconomic status with successful ageing: Differences in the components of successful ageing. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2009, 41, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, C.N.; Natelson Love, M.C.; Triebel, K.L. Normal cognitive aging. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2013, 29, 737–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depp, C.; Vahia, I.V.; Jeste, D. Successful aging: Focus on cognitive and emotional health. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 6, 527–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitina, M.; Young, S.; Zhavoronkov, A. Psychological aging, depression, and wellbeing. Aging 2020, 12, 18765–18777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Ballbé, Ó.; Martin-Moratinos, M.; Saiz, J.; Gallardo-Peralta, L.; Barrón López de Roda, A. The Relationship between Subjective Ageing and Cognition in Elderly People: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 3115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tully-Wilson, C.; Bojack, R.; Millear, P.M.; Stallman, H.M.; Allen, A.; Mason, J. Self-perceptions of ageing: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Psychol. Aging 2021, 36, 773–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velaithan, V.; Tan, M.M.; Yu, T.F.; Liem, A.; The, P.L.; Su, T.T. The Association of Self-Perception of Ageing and Quality of Life in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Gerontologist 2024, 64, gnad041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Center for Social Welfare Policy and Research. The End of “Active Ageing”. Available online: https://www.euro.centre.org/publications/detail/4727 (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Mitchell, D.M.; Henry, A.J.; Ager, R.D. COVID-19 impacts and interventions for older adults: Implications for future disasters. J. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2023, 71, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, N.R.; Neumann, J.T.; McNeil, J.J.; Cheng, A.C. Implications of COVID-19 for an ageing population. Med. J. Aust. 2020, 213, 342–344.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, A.; Khan, M.A. Social isolation, loneliness, and mental health among older adults during COVID-19: A scoping review. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2024, 67, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briere, J.; Wang, S.H.; Khanam, U.A.; Lawson, J.; Goodridge, D. Quality of life and wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic: Associations with loneliness and social isolation in a cross-sectional, online survey of 2,207 community-dwelling older Canadians. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrer-Merk, E.; Reyes-Rodriguez, M.F.; Soulsby, L.K.; Roper, L.; Bennett, K.M. Older adults’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative systematic literature review. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izekenova, A.; Izekenova, A.; Sukenova, D.; Nikolic, D.; Chen, Y.; Rakhmatullina, A.; Nurbakyt, A. Factors Associated with Loneliness and Psychological Distress in Older Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Kazakhstan: A Cross-Sectional Study. Medicina 2025, 61, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins Van Jaarsveld, G. The Effects of COVID-19 Among the Elderly Population: A Case for Closing the Digital Divide. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 577427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adhikari, R.; Shah, R.; Ghimire, K.; Khanal, B.; Baral, S.; Adhikari, A.; Malla, D.K.; Khanal, V. The Quality of Life and Associated Factors Among Older Adults in Central Nepal: A Cross-Sectional Study Using the WHOQOL-OLD Tool. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzo, R.R.; Khanal, P.; Shrestha, S.; Mohan, D.; Myint, P.K.; Su, T.T. Determinants of active aging and quality of life among older adults: Systematic review. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1193789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çiftci, N.; Yıldız, M.; Yıldırım, Ö. The effect of health literacy and health empowerment on quality of life in the elderly. Psychogeriatrics 2023, 23, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Healthy Ageing and Functional Ability. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/healthy-ageing-and-functional-ability (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Siqeca, F.; Yip, O.; Mendieta, M.J.; Schwenkglenks, M.; Zeller, A.; De Geest, S.; Zúñiga, F.; Stenz, S.; Briel, M.; Quinto, C.; et al. Factors associated with health-related quality of life among home-dwelling older adults aged 75 or older in Switzerland: A cross-sectional study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2022, 20, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geigl, C.; Loss, J.; Leitzmann, M.; Janssen, C. Social factors of health-related quality of life in older adults: A multivariable analysis. Qual. Life Res. 2023, 32, 3257–3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Wei, H.; Mo, H.; Yang, G.; Wan, L.; Dong, H.; He, Y. Impacts of chronic diseases and multimorbidity on health-related quality of life among community-dwelling elderly individuals in economically developed China: Evidence from cross-sectional survey across three urban centers. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2024, 22, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwano, S.; Kambara, K.; Aoki, S. Psychological Interventions for Wellbeing in Healthy Older Adults: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Happiness Stud. 2022, 23, 2389–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, G.J.; Tanenbaum, S. Psychotherapy with older adults. Am. J. Psychother. 2000, 54, 386–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsman, A.K.; Schierenbeck, I.; Wahlbeck, K. Psychosocial interventions for the prevention of depression in older adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Aging Health 2011, 23, 387–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, L.; Moyle, W.; Jones, C.; Todorovic, M. Psychosocial interventions for pain management in older adults with dementia: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J. Adv. Nurs. 2019, 75, 1608–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lucia, A.; Perlini, C.; Chiarotto, A.; Pachera, S.; Pasini, I.; Del Piccolo, L.; Donisi, V. eHealth-Integrated Psychosocial and Physical Interventions for Chronic Pain in Older Adults: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e55366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keefe, F.J.; Porter, L.; Somers, T.; Shelby, R.; Wren, A.V. Psychosocial interventions for manageing pain in older adults: Outcomes and clinical implications. Br. J. Anaesth. 2013, 111, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.A.; Choi, S.H.; Lee, W.J.; Jang, J.H.; Moon, J.Y.; Kim, Y.C.; Kang, D.H. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with chronic pain: Implications of gender differences in empathy. Medicine 2018, 97, e10867. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.W.; Ng, G.Y.F.; Chung, R.C.K.; Ng, S.S.M. Cognitive behavioural therapy for fear of falling and balance among older people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 2018, 47, 520–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, P. Cognitive behavioural therapy with older people. Maturitas 2013, 76, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.N.; Tao, H.; Wang, M.; Yu, H.W.; Su, H.; Wu, B. Efficacy of path-oriented psychological self-help interventions to improve mental health of empty-nest older adults in the Community of China. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Rao, W.; Su, Y.; Sul, Y.; Caron, G.; D’Arcy, C.; Fleury, M.J.; Meng, X. Psychological interventions for loneliness and social isolation among older adults during medical pandemics: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 2023, 52, afad076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klausner, E.J.; Alexopoulos, G.S. The future of psychosocial treatments for elderly patients. Psychiatr. Serv. 1999, 50, 1198–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilotto, A.; Boi, R.; Petermans, J. Technology in geriatrics. Age Ageing 2018, 47, 771–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit-Dubé, L.; Jean, E.K.; Aguilar, M.A.; Zuniga, A.M.; Bier, N.; Couture, M.; Lussier, M.; Lajoie, X.; Belchior, P. What facilitates the acceptance of technology to promote social participation in later life? A systematic review. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2023, 18, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, T.; Dodds, L.; Georgiou, A.; Gewald, H.; Siette, J. Older Adults and New Technology: Mapping Review of the Factors Associated With Older Adults’ Intention to Adopt Digital Technologies. JMIR Aging 2023, 6, e44564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Weina, H.; Yan, D. Digital literacy impacts quality of life among older adults through hierarchical mediating mechanisms. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaja, S.J.; Charness, N.; Rogers, W.A.; Sharit, J.; Moxley, J.H.; Boot, W.R. The Benefits of Technology for Engaging Aging Adults: Findings From the PRISM 2.0 Trial. Innov. Aging 2024, 8, igae042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yunus, M.M.; Hussain, R.B.B.M.; Lin, W. Cultural adaptation to aging: A study on digital cultural adaptation needs of Chinese older adults based on KANO model. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1554552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siette, J.; Dodds, L.; Seaman, K.; Wuthrich, V.; Johnco, C.; Earl, J.; Dawes, P.; Westbrook, J.I. The impact of COVID-19 on the quality of life of older adults receiving community-based aged care. Australas. J. Ageing 2021, 40, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haase, K.R.; Cosco, T.; Kervin, L.; Riadi, I.; O’Connell, M.E. Older Adults’ Experiences with Using Technology for Socialization During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Cross-sectional Survey Study. JMIR Aging 2021, 4, e28010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, B.; Yang, J.; Wong, F.K.Y.; Wong, A.K.C.; Ma, T.; Meng, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Q. Artificial intelligence in elderly healthcare: A scoping review. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 83, 101808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDaniel, L.; Essien, I.; Lefcourt, S.; Zelleke, E.; Sinha, A.; Chellappa, R.; Abadir, P.M. Aging With Artificial Intelligence: How Technology Enhances Older Adults’ Health and Independence. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2025, 80, glaf086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Allen, J. Bridging the Gap: The Role of AI in Enhancing Psychological Wellbeing Among Older Adults. Psychol. Int. 2025, 7, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Y.; Li, J.; Zhu, N.L.; Luo, L.; Zhang, S.Y.; Cheng, W.W.; Li, J.X.; Yu, C.; Lu, S.H.; Zhu, L. When “Aging” meets “Intelligence”: Smart health cognition and intentions of older adults in rural Western China. Front. Psychiatry 2025, 15, 1493376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budak, K.B.; Atefi, G.; Hoel, V.; Uribe, F.L.; Meiland, F.; Teupen, S.; Felding, S.A.; Roes, M. Can technology impact loneliness in dementia? A scoping review on the role of assistive technologies in delivering psychosocial interventions in long-term care. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2023, 18, 1107–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, S.I.; Van Citters, A.D.; Mueser, K.T.; Bartels, S.J. Psychosocial rehabilitation on older adults with serious mental illness: A review of the research literature and recommendations for development of rehabilitative approaches. Am. J. Psychiatr. Rehabil. 2008, 11, 7–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leff, B.; Ritchie, C.S.; Rising, K.L.; Cannon, K.; Wardlow, L. Addressing barriers to equitable telehealth for older adults. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1483366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M. Older people’s attitudes towards emerging technologies: A systematic literature review. Public Underst. Sci. 2023, 32, 948–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.H.; Damnée, S.; Kerhervé, H.; Ware, C.; Rigaud, A.S. Bridging the digital divide in older adults: A study from an initiative to inform older adults about new technologies. Clin. Interv. Aging 2015, 10, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepburn, J.; Williams, L.; McCann, L. Barriers to and Facilitators of Digital Health Technology Adoption Among Older Adults With Chronic Diseases: Updated Systematic Review. JMIR Aging 2025, 8, e80000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Cheng, X.; Li, D.; Meng, X. The Digital Divide of Older People in Communities: Urban-Rural, Gender, and Health Disparities and Inequities. Health Soc. Care Community 2025, 2025, 1361214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olatunji, S.A.; Shim, J.S.; Syed, A.; Tsai, Y.L.; Pereira, A.E.; Mahajan, H.P.; Mudar, R.A.; Rogers, W.A. Robotic support for older adults with cognitive and mobility impairments. Front. Robot. AI 2025, 12, 1545733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Kim, J.S.; Yu, S. The impact of care robots on older adults: A systematic review. Geriatr. Nurs. 2025, 65, 103507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zguda, P.; Radosz-Knawa, Z.; Kukier, T.; Radosz, M.; Kamińska, A.; Indurkhya, B. How Do Older Adults Perceive Technology and Robots? A Participatory Study in a Care Center in Poland. Electronics 2025, 14, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggar, C.; Sorwar, G.; Seton, C.; Penman, O.; Ward, A. Smart home technology to support older people’s quality of life: A longitudinal pilot study. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2023, 18, e12489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Li, G.; Jiang, S.; Liu, Y.; Leng, M.; Zhao, J.; Wang, S.; Meng, X.; Shang, B.; Chen, L.; et al. The effect of smart homes on older adults with chronic conditions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Geriatr. Nurs. 2019, 40, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadowaki, L.; Wister, A. Older Adults and Social Isolation and Loneliness During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Integrated Review of Patterns, Effects, and Interventions. Can. J. Aging 2023, 42, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Barriers | References | |

|---|---|---|

| Access and digital divide |

| [88,89,90] |

| Personal factors |

| [89,91] |

| Factors affecting the digital divide | ||

| Access divide (AD) |

| [92] |

| Use divide (UD) |

| |

| Knowledge divide (KD) |

| |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sukenova, D.; Nikolic, D.; Izekenova, A.; Nurbakyt, A.; Izekenova, A.; Macijauskiene, J. Ageing and Quality of Life in Older Adults: Updates and Perspectives of Psychosocial and Advanced Technological Interventions. Healthcare 2026, 14, 217. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14020217

Sukenova D, Nikolic D, Izekenova A, Nurbakyt A, Izekenova A, Macijauskiene J. Ageing and Quality of Life in Older Adults: Updates and Perspectives of Psychosocial and Advanced Technological Interventions. Healthcare. 2026; 14(2):217. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14020217

Chicago/Turabian StyleSukenova, Dinara, Dejan Nikolic, Aigulsum Izekenova, Ardak Nurbakyt, Assel Izekenova, and Jurate Macijauskiene. 2026. "Ageing and Quality of Life in Older Adults: Updates and Perspectives of Psychosocial and Advanced Technological Interventions" Healthcare 14, no. 2: 217. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14020217

APA StyleSukenova, D., Nikolic, D., Izekenova, A., Nurbakyt, A., Izekenova, A., & Macijauskiene, J. (2026). Ageing and Quality of Life in Older Adults: Updates and Perspectives of Psychosocial and Advanced Technological Interventions. Healthcare, 14(2), 217. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14020217