Evaluating the Effectiveness of a School-Based Mental Health Training Programme: The Transformative, Resilient, Youth-Led (TRY) Gym

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. How Schools, Family, and Characteristics of Adolescent Developmental Stage Influence Academic Stress in Secondary School Students

1.1.1. Familial Factors and Academic Stress

1.1.2. School Factors and Academic Stress

1.1.3. Characteristics of Adolescent Developmental Stage

1.2. Response from Government—Three-Tier School-Based Emergency Mechanism

1.3. Preventive School-Based Mental Health Programmes

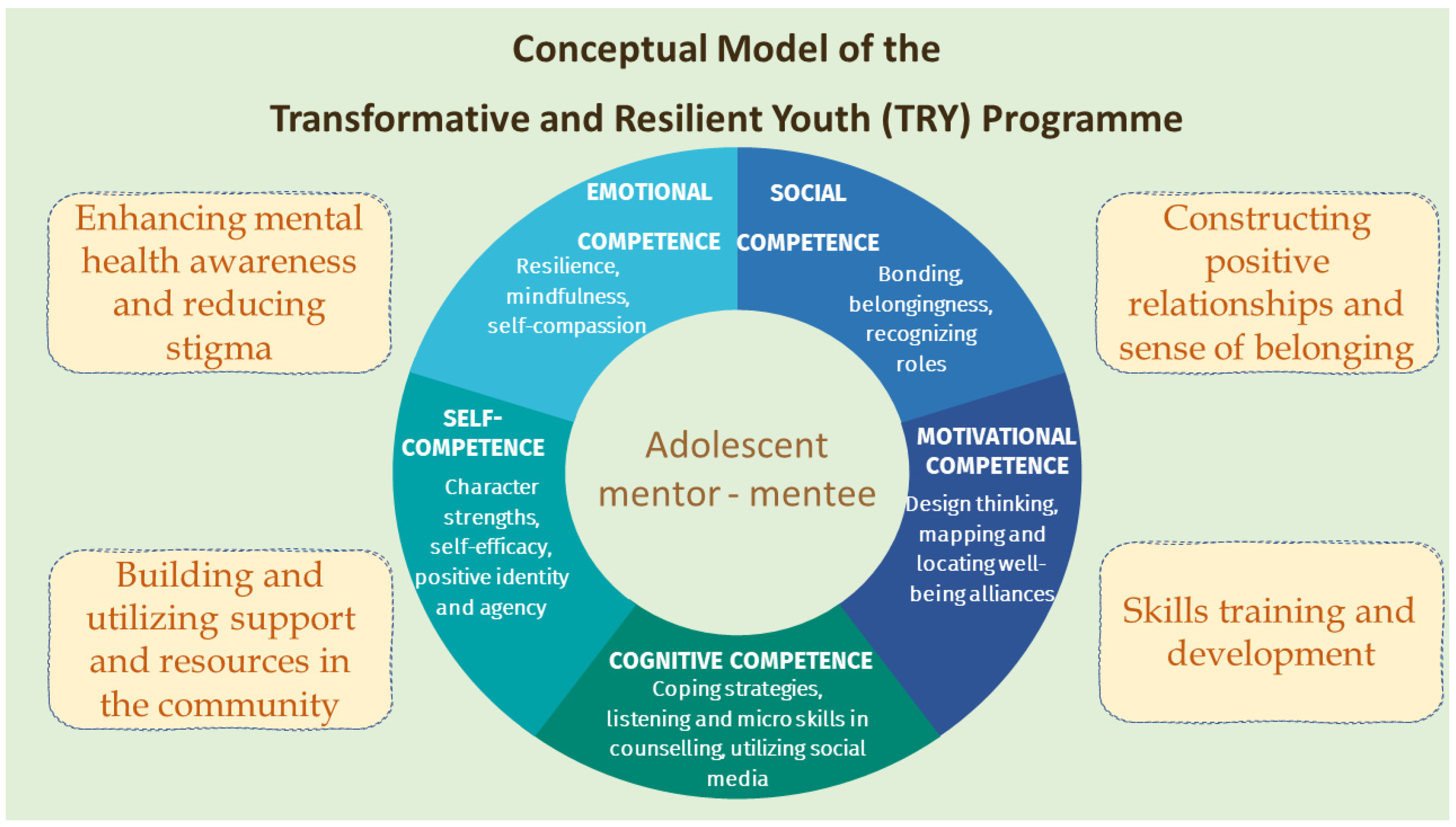

1.4. The Theoretical Framework Underlying the TRY Gym Programme

1.5. Project Objectives and Research Hypothesis

- To train a group of secondary students aged between 15 and 18 to be the youth mentors (trainees) with coping strategies, self-compassion, counselling, and empathic listening skills to increase their awareness of their own resilience and emotional competence. Trainees are expected to hang out with their peers/mentees with these skills.

- To construct positive relationships and a sense of belonging among adolescents. The programme will enhance the strengths of trainees to co-create timely, relevant, youth-driven online and/or onsite multimedia mental health educational projects for their peers/mentees in schools (aged 12–18) and people in the communities.

- To create a stigma-free and strengths-building platform to increase mental health literacy amongst trainees and their peers/mentees through online and onsite multimedia mental health educational projects.

- To develop the capability of trainees to identify their strengths and utilize support and resources in the community to build reciprocal support networks among trainees, their mentees, and the community.

- To promote positive youth development and the mental well-being of trainees and participating adolescents.

2. Materials and Methods

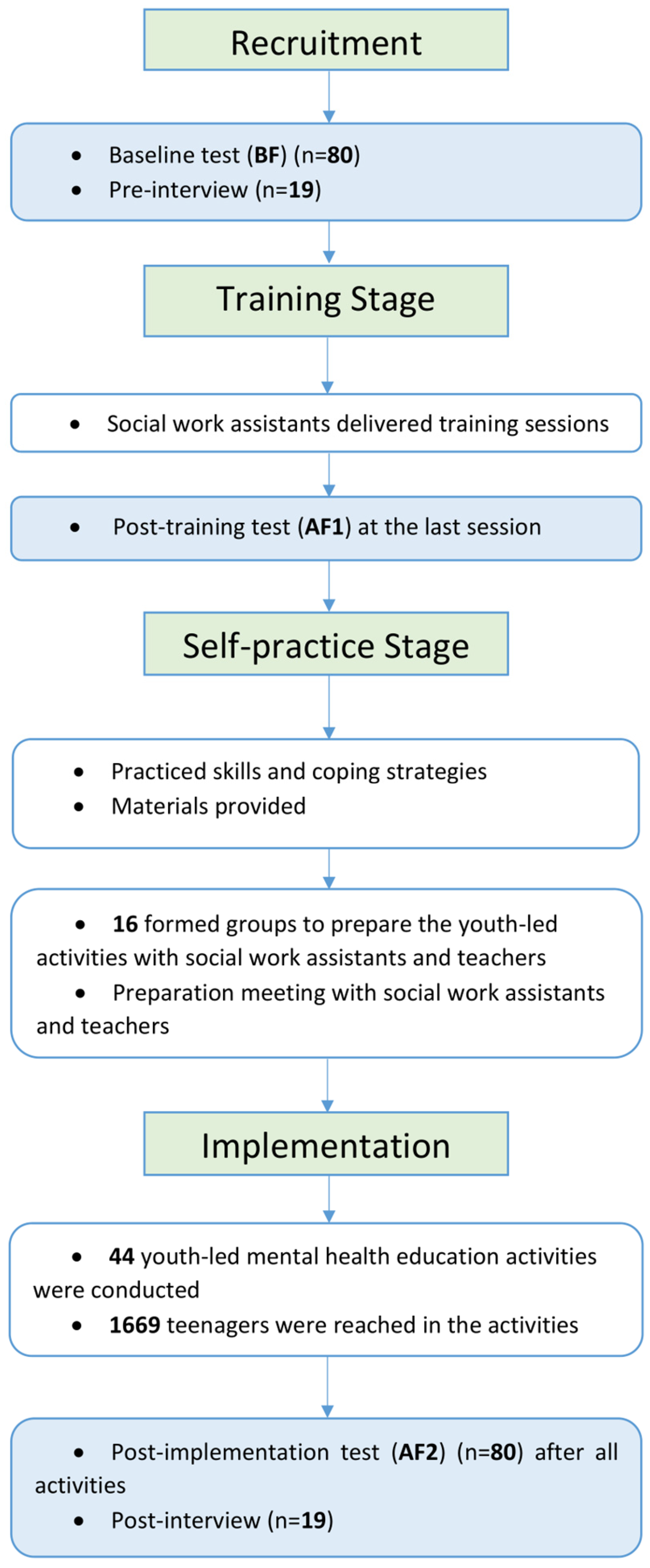

2.1. Participants and Recruitment

2.2. Programme Outline

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Assessment of Positive Youth Development

2.3.2. The Revised Motivation Scale, the Student Opinion Scale (SOS)

2.3.3. The Perceived Devaluation-Discrimination Scale

2.3.4. The Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS)

2.3.5. Self-Compassion Scale for Youth

2.3.6. Strengths Use and Current Knowledge Scale

2.3.7. Mental Help-Seeking Attitudes Scale (MHSAS)

2.3.8. Qualitative Interviews

2.4. Procedures

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Demographics Information

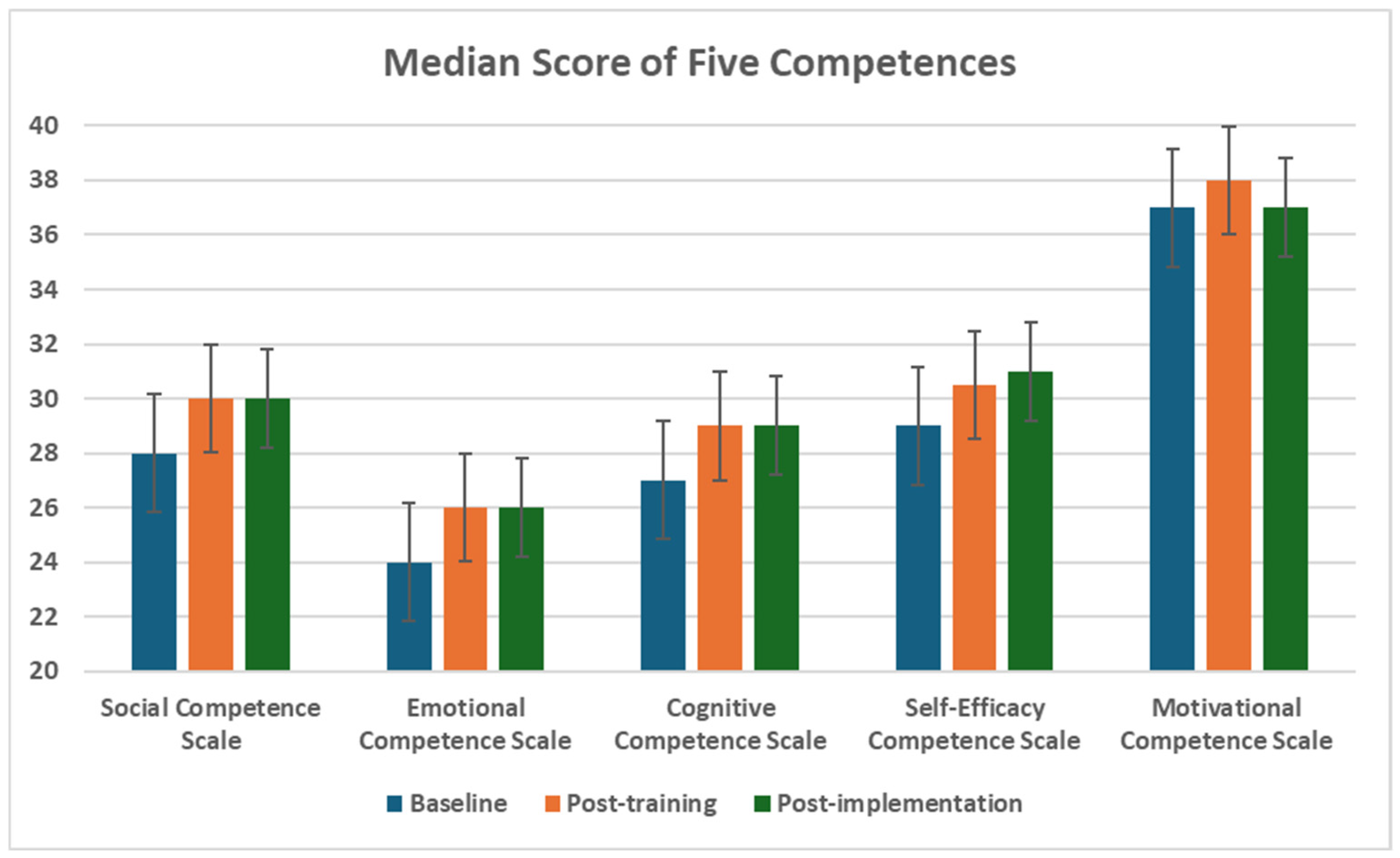

3.2. Quantitative Results

3.2.1. Survey Results

Social Competence

Cognitive Competence

Emotional Competence

Self-Efficacy Competence

Motivational Competence

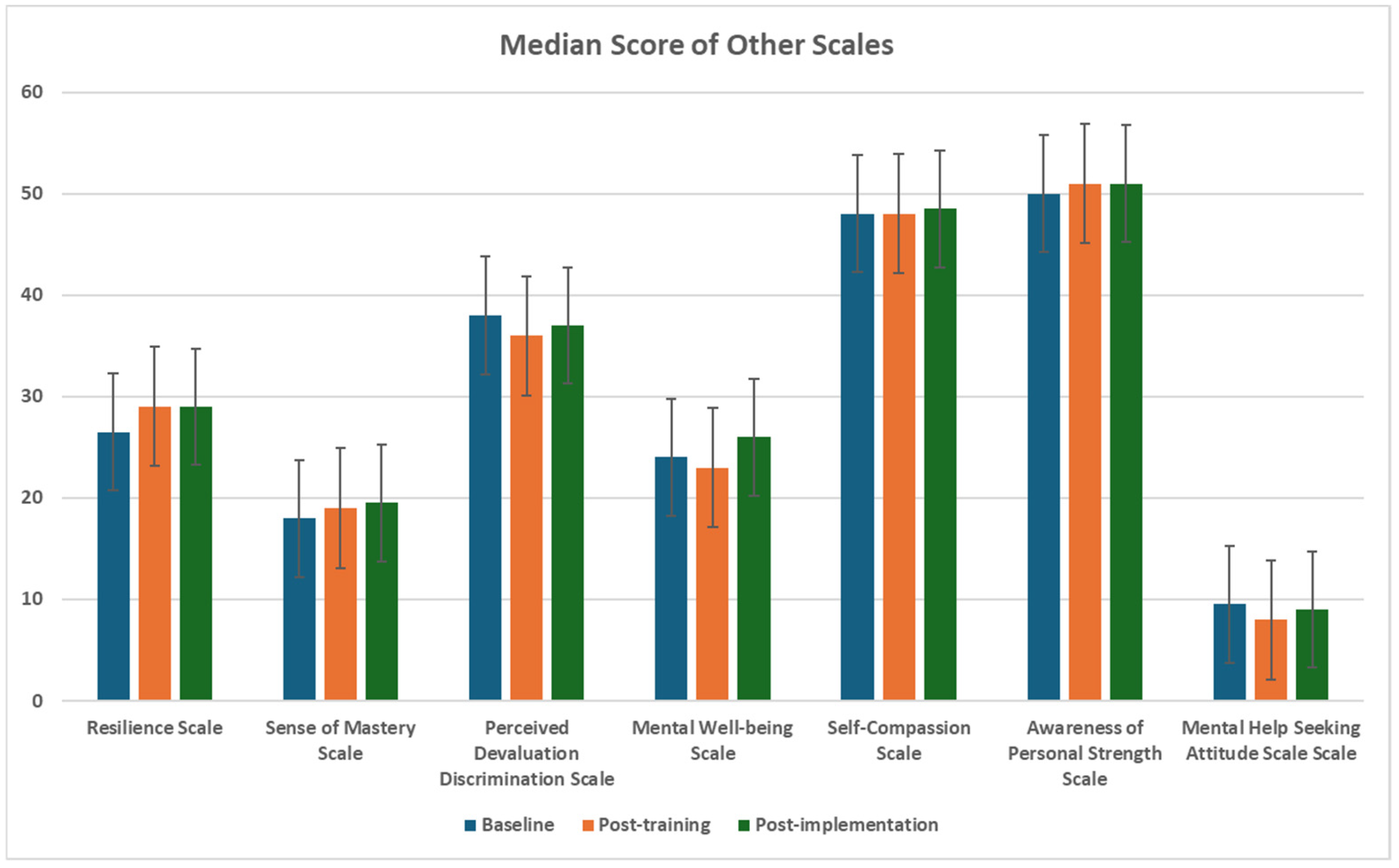

Misconceptions and Negative Attitudes Toward Mental Disorders

Well-Being

Opinions About TRY Gym

3.3. Group Interview Results

3.3.1. Emotional Competence

I was easy to lose temper, but now I figure out how to control it.(Trainee no. 3-2-4. Male, 17 y/o, family income: HKD 10,001–20,000, housing type: HOS, Cantonese speaker.)

It has made my mood swings smaller than before, and my emotions are more stable.(Trainee no. 4-2-9. Female, 15 y/o, family income: not sure, housing type: private, Cantonese speaker.)

Except for being judgmental, I also need to care for myself. I think I learnt how to change my mentality on this.(Trainee no. 4-1-3. Female, 15 y/o, family income: not sure, housing type: private, Cantonese speaker.)

I think I am much better in mental health than before. I don’t overthink the negative stuff. Before if I got a bad score in a quiz, I would feel so screwed. Now I feel more confident.(Trainee no. 3-2-4. Male, 17 y/o, family income: HKD 10,001–20,000, housing type: HOS, Cantonese speaker.)

3.3.2. Social Competence

Because, you know, like high school gossip, some people have difficulties in their mental health. So, yeah, whenever I encounter those people that I’ve heard that they’re struggling mentally, I just become more careful and act normal.(Trainee no. 2-2-15. Female, 15 y/o, family income: not sure, housing type: private, English speaker.)

However, I pay attention to other people’s emotions. I have noticed that if someone around me is unhappy, I will quickly try to understand or meet them face-to-face. In the past, I would constantly say comforting words to them and try to instil my own ideas. But now I have learned to support them and be there for them with genuine companionship.(Trainee no. 3-2-2. Male, 17 y/o, family income: HKD 10,001–20,000, housing type: monthly rental, Cantonese speaker.)

I seldom talk to strangers. But after this programme, for example, when I was at the food court, and I shared a table with a stranger. If I felt he wanted to talk to me, then I could start conversations, just being more extroverted.(Trainee no. 1-2-8. Male, 16 y/o, family income: not sure, housing type: public, Cantonese speaker.)

I am in the higher form, so I am older than the other participants in the events. After getting to know them, I am more willing to meet new people and make friends. I am open to chatting with them and expanding my own social circle.(Trainee no. 1-2-4. Male, 16 y/o, family income: HKD 30,001–40,000, housing type: private, Cantonese speaker.)

3.3.3. Motivational Competence

When we were preparing activities, what gave me the deepest impression was that we needed to design games and props for the games. And we Care Ambassadors also prepared and packed more than 20 gifts. Most of us had been preparing for hours, and that’s a long time.(Trainee no. 1-2-8. Male, 16 y/o, family income: not sure, housing type: public, Cantonese speaker.)

I learned about team spirit and how to express my emotions. In the past, when forced to do something, I would choose to remain silent, but now I actively express my thoughts.(Trainee no. 4-2-2, Female, 14 y/o, family income: not sure, housing type: HOS, Cantonese speaker.)

3.3.4. Cognitive Competence

So, I feel like that was also very meaningful and like ways to talk to people and like counselling and like yeah, just talking to people with. It’s a little bit more sensitive in general.(Trainee no. 2-2-17. Female, 16 y/o, family income: not sure, housing type: private, English speaker.)

I have now learned how to better communicate with others, understand their feelings, and practice empathy. I used to be someone who was centred on my own feelings. Now, when I talk or argue with others, I try to put myself in their shoes and consider their thoughts or feelings.(Trainee no. 1-1-1. Female, 15 y/o, family income: not sure, housing type: private, Putonghua speaker.)

I learnt to do the meditation. Now, when I feel stressed, I will meditate to relieve stress. I think the skill can help me a lot.(Trainee no. 1-1-11. Female, 15 y/o, family income: HKD 40,001–50,000, housing type: public, Cantonese speaker.)

I felt like before the programme, I was often suspicious and worried, sometimes being anxious over things that didn’t need concern, or just experiencing fear for no reason. But after participating in the programme I realized that there are many ways to help relieve stress. I also learned that many things aren’t as tense or difficult as I imagined, and I don’t need to be so fixated on them. Some issues can be solved quite easily. Perhaps by actively seeking help from friends, reaching out to those around you, or doing something very simple.(Trainee no. 2-1-4. Male, 15 y/o, family income: not sure, housing type: private, Cantonese speaker.)

3.3.5. Self-Competence

And then there were things like, what was really like impactful towards me in that session was that writing my weaknesses was really easy, but then writing my strengths, I couldn’t really think of anything. So, I mean, reflect on myself a lot.(Trainee no. 2-2-15. Female, 15 y/o, family income: not sure, housing type: private, English speaker.)

I feel that my perspective on myself has changed. I used to think that others were living well and that my own existence seemed useless. Now I feel that my sense of self-worth has improved.(Trainee no. 4-2-2. Female, 14 y/o, family income: not sure, housing type: HOS, Cantonese speaker.)

I feel my attitude towards life has been changed. I am more optimistic and complain less than before.(Trainee no. 4-2-2. Female, 14 y/o, family income: not sure, housing type: HOS, Cantonese speaker.)

I feel that I have become more optimistic. I was originally quite a pessimistic person, so I feel more optimistic now. In the past, when I was more pessimistic and didn’t really believe in myself, I felt that things were pretty bad.(Trainee no. 3-2-3. Male, 16 y/o, family income: HKD 10,001–20,000, housing type: public, Cantonese speaker.)

3.3.6. Unique Features of TRY Gym

Human Library Sharing from Persons in Mental Recovery

Relaxing and Inclusive Space for Trainees

Hands-On Experiences of Organizing Youth-Led Activities

4. Discussion and Summary

4.1. Programme Outcome

4.2. Hypothesis Set 1: 5 Core Competencies

4.2.1. Social Competence

4.2.2. Emotional Competence

4.2.3. Cognitive Competence

4.2.4. Self-Competence

4.2.5. Motivational Competence

4.3. Hypothesis Set 2: Misconceptions, Negative Attitudes, and Stigma Toward Mental Disorders

4.4. Hypothesis Set 3: Overall Mental Well-Being

4.5. Limitations

4.6. Future Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Mental Health of Adolescents. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China. Youth Development Blueprint: Inspire Our Youths Brighten Our Future; The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China: Hong Kong, China, (n.d.). [Google Scholar]

- Legislative Council Secretariat, Research and Information Division. Mental Health of Local Students (No. ISSH22/2024). 2024. Available online: https://app7.legco.gov.hk/rpdb/en/uploads/2024/ISSH/ISSH22_2024_20241028_en.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Yiu, W. Over 90% of Student Suicides in Hong Kong Were Aged 12 and Above. South China Morning Post. 2 April 2025. Available online: https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/education/article/3304957/over-90-student-suicides-hong-kong-were-youngsters-aged-12-and-above?module=perpetual_scroll_0&pgtype=article (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Department of Health, Student Health Service. Student Health Service Annual Health Report for 2023/24 School Year. 2025. Available online: https://www.studenthealth.gov.hk/english/annual_health/files/student_health_service_annual_health_report_for_2023_24_school_year.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Yeong, B. Hong Kong Suicide Press Database [Data Set]. 2024. Available online: http://hkspd.siuyeong.com (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong. CUHK Announces Survey Results on the Mental Health of Local Child, Adolescent and Elderly Populations. 29 November 2023. Available online: https://www.med.cuhk.edu.hk/press-releases/cuhk-announces-survey-results-on-the-mental-health-of-local-child-adolescent-and-elderly-populations (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Kim, C.; Seockhoon, C.; Suyeon, L.; Soyoun, Y.; Boram, P. Perfectionism is related with academic stress in medical student. Eur. Psychiatry 2017, 41, S690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Lee, M. The reciprocal longitudinal relationship between the parent-adolescent relationship and academic stress in Korea. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2013, 41, 1519–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-F.; Heppner, P.P. Assessing the impact of parental expectations and psychological distress on Taiwanese college students. Couns. Psychol. 2002, 30, 582–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandewater, E.A.; Lansford, J.E. A family process model of problem behaviors in adolescents. J. Marriage Fam. 2005, 67, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conger, R.D.; Conger, K.J.; Martin, M.J. Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. J. Marriage Fam. 2010, 72, 685–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prior, V.; Glaser, D. Understanding Attachment and Attachment Disorders: Theory, Evidence and Practice; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mercer, J. Understanding Attachment: Parenting, Child Care, and Emotional Development; Bloomsbury Publishing USA: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. A Secure Base: Clinical Applications of Attachment Theory; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, G.S.; Yeung, K.C.; Wong, D.F. Academic stressors and anxiety in children: The role of paternal support. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2010, 19, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.B.; Yates, S. Academic expectations as sources of stress in Asian students. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2011, 14, 389–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazel, N.A.; Oppenheimer, C.W.; Technow, J.R.; Young, J.F.; Hankin, B.L. Parent relationship quality buffers against the effect of peer stressors on depressive symptoms from middle childhood to adolescence. Dev. Psychol. 2014, 50, 2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, S.N.; McGee, R.; Stanton, W.R. Perceived attachments to parents and peers and psychological well-being in adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 1992, 21, 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, R.P.; Huan, V.S. Relationship between academic stress and suicidal ideation: Testing for depression as a mediator using multiple regression. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2006, 37, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sue, S.; Okazaki, S. Asian-American educational achievements: A phenomenon in search of an explanation. Am. Psychol. 1990, 45, 913–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, M.H. The Psychology of the Chinese People; Chinese University Press: Hong Kong, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, D.Y. Continuity and variation in Chinese patterns of socialization. J. Marriage Fam. 1989, 51, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kwak, K.; Lee, S. Does Optimism Moderate Parental Achievement Pressure and Academic Stress in Korean Children? Curr. Psychol. 2016, 35, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleg, O.; Deutch, C.; Dan, O. Test anxiety among female college students and its relation to perceived parental academic expectations and differentiation of self. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2016, 49, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadach, E.; Ganor-Miller, O. The role of perceived parental over-involvement in student test anxiety. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2013, 28, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.; Salili, F.; Ho, S.Y.; Mak, K.H.; Lai, M.K.; Lam, T.H. The Perceptions of Adolescents, Parents and Teachers on the Same Adolescent Health Issues. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2005, 26, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landstedt, E.; Gådin, K.G. Seventeen and stressed—Do gender and class matter? Health Sociol. Rev. 2012, 21, 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderman, E.M. School effects on psychological outcomes during adolescence. J. Educ. Psychol. 2002, 94, 795–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Dunne, M.P.; Hou, X.; Xu, A. Educational stress among Chinese adolescents: Individual, family, school and peer influences. Educ. Rev. 2013, 65, 284–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, V.; Seidman, E. A systems framework for understanding social settings. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2007, 39, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J.S.; Midgley, C.; Wigfield, A.; Buchanan, C.M.; Reuman, D.; Flanagan, C.; Mac Iver, D. Development during adolescence: The impact of stage-environment fit on young adolescents’ experiences in schools and in families. Am. Psychol. 1993, 48, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eccles, J.S.; Roeser, R.W. Schools as Developmental Contexts During Adolescence. J. Res. Adolesc. 2011, 21, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.-T.; Eccles, J.S. School context, achievement motivation, and academic engagement: A longitudinal study of school engagement using a multidimensional perspective. Learn. Instr. 2013, 28, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, A.; Cohen, J.; Guffey, S.; Higgins-D’Alessandro, A. A Review of School Climate Research. Rev. Educ. Res. 2013, 83, 357–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.-T.; Degol, J.L. School Climate: A Review of the Construct, Measurement, and Impact on Student Outcomes. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 28, 315–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadyaya, K.; Salmela-Aro, K. Development of School Engagement in Association with Academic Success and Well-Being in Varying Social Contexts: A Review of Empirical Research. Eur. Psychol. 2013, 18, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chyu, E.P.Y.; Chen, J.-K. The Correlates of Academic Stress in Hong Kong. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christophersen, K.-A.; Elstad, E.; Turmo, A. The Nature of Social Practice Among School Professionals: Consequences of the Academic Pressure Exerted by Teachers in Their Teaching. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2011, 55, 639–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, V.E.; Smith, J.B. Social Support and Achievement for Young Adolescents in Chicago: The Role of School Academic Press. Am. Educ. Res. J. 1999, 36, 907–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lu, Z. Chinese High School Students’ Academic Stress and Depressive Symptoms: Gender and School Climate as Moderators. Stress Health 2012, 28, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shochet, I.M.; Dadds, M.R.; Ham, D.; Montague, R. School Connectedness Is an Underemphasized Parameter in Adolescent Mental Health: Results of a Community Prediction Study. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2006, 35, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaworska, N.; MacQueen, G. Adolescence as a unique developmental period. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2015, 40, 291–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sisk, L.M.; Gee, D.G. Stress and adolescence: Vulnerability and opportunity during a sensitive window of development. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 44, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engel, M.L.; Gunnar, M.R. The development of stress reactivity and regulation during human development. In International Review of Neurobiology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Volume 150, pp. 41–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, B.J.; Figueredo, A.J.; Brumbach, B.H.; Schlomer, G.L. Fundamental Dimensions of Environmental Risk: The Impact of Harsh versus Unpredictable Environments on the Evolution and Development of Life History Strategies. Hum. Nat. 2009, 20, 204–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankenhuis, W.E.; Walasek, N. Modeling the evolution of sensitive periods. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2020, 41, 100715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePasquale, C.E.; Donzella, B.; Gunnar, M.R. Pubertal recalibration of cortisol reactivity following early life stress: A cross-sectional analysis. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2019, 60, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnar, M.R.; DePasquale, C.E.; Reid, B.M.; Donzella, B.; Miller, B.S. Pubertal stress recalibration reverses the effects of early life stress in postinstitutionalized children. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 23984–23988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luby, J.L.; Baram, T.Z.; Rogers, C.E.; Barch, D.M. Neurodevelopmental Optimization after Early-Life Adversity: Cross-Species Studies to Elucidate Sensitive Periods and Brain Mechanisms to Inform Early Intervention. Trends Neurosci. 2020, 43, 744–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, B.; Luna, B. Adolescence as a neurobiological critical period for the development of higher-order cognition. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2018, 94, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Harmelen, A.-L.; Kievit, R.A.; Ioannidis, K.; Neufeld, S.; Jones, P.B.; Bullmore, E.; Dolan, R.; The NSPNConsortium; Fonagy, P.; Goodyer, I. Adolescent friendships predict later resilient functioning across psychosocial domains in a healthy community cohort. Psychol. Med. 2017, 47, 2312–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roach, A. Supportive Peer Relationships and Mental Health in Adolescence: An Integrative Review. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2018, 39, 723–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahi, R.S.; Ninova, E.; Silvers, J.A. With a little help from my friends: Selective social potentiation of emotion regulation. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2021, 150, 1237–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979; Volume 352. [Google Scholar]

- Government Launches Three-Tier School-Based Emergency Mechanism. Press Releases, The Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. 1 December 2023. Available online: https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/202312/01/P2023120100650.htm (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Available online: https://www.stheadline.com/society/3384991/%E5%AD%B8%E7%AB%A5%E8%87%AA%E6%AE%BA%E8%91%89%E5%85%86%E8%BC%9D%E4%B8%89%E5%B1%A4%E6%A9%9F%E5%88%B6%E4%B8%8B%E5%AD%B8%E7%94%9F%E6%88%96%E6%88%90%E4%BA%BA%E7%90%83-%E9%98%B2%E7%A6%A6%E5%B7%A5%E4%BD%9C%E4%B8%8D%E8%B6%B3%E6%B0%B8%E9%81%A0%E9%83%BD%E5%9C%A8%E8%BF%BD%E8%90%BD%E5%BE%8C (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Sum, M.Y.; Chan, S.K.W.; Tsui, H.K.H.; Wong, G.H.Y. Stigma towards mental illness, resilience, and help-seeking behaviours in undergraduate students in Hong Kong. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2024, 18, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, C.C.; Bronstein, J. Easing the path for improving help-seeking behaviour in youth. eClinicalMedicine 2020, 18, 100256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.; Chan, C. Promotion of Adolescent Mental Health in Hong Kong—The Role of a Comprehensive Child Health Policy. J. Adolesc. Health 2019, 64, S14–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China. LCQ21: Promoting Student Mental Health. Press Releases, The Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. 16 April 2025. Available online: https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/202504/16/P2025041600320.htm?fontSize=1 (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Singh, V.; Kumar, A.; Gupta, S. Mental Health Prevention and Promotion—A Narrative Review. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 898009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockings, E.A.; Degenhardt, L.; Dobbins, T.; Lee, Y.Y.; Erskine, H.E.; Whiteford, H.A.; Patton, G. Preventing depression and anxiety in young people: A review of the joint efficacy of universal, selective and indicated prevention. Psychol. Med. 2016, 46, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, K.Y.C.; Hung, S.-F.; Lee, H.W.S.; Leung, P.W.L. School-Based Mental Health Initiative: Potentials and Challenges for Child and Adolescent Mental Health. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 866323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazel, M.; Hoagwood, K.; Stephan, S.; Ford, T. Mental health interventions in schools in high-income countries. Lancet Psychiatry 2014, 1, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostaszewski, K. The importance of resilience in adolescent mental health promotion and risk behaviour prevention. Int. J. Public Health 2020, 65, 1221–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, E.S.Y.; Kwok, C.-L.; Wong, P.W.C.; Fu, K.-W.; Law, Y.-W.; Yip, P.S.F. The Effectiveness and Sustainability of a Universal School-Based Programme for Preventing Depression in Chinese Adolescents: A Follow-Up Study Using Quasi-Experimental Design. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kallio, J.; Honkatukia, P. Everyday Resistance in Making Oneself Visible: Young Adults’ Negotiations with Institutional Social Control in Youth Services. Int. J. Child Youth Fam. Stud. 2022, 13, 98–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.B.; Weavers, B.; Lomax, T.; Meilak, E.; Eyre, O.; Powell, V.; Mars, B.; Rice, F. Formal and informal mental health support in young adults with recurrently depressed parents. medRXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurenzi, C.A.; Du Toit, S.; Mawoyo, T.; Luitel, N.P.; Jordans, M.J.D.; Pradhan, I.; Van Der Westhuizen, C.; Melendez-Torres, G.J.; Hawkins, J.; Moore, G.; et al. Development of a school-based programme for mental health promotion and prevention among adolescents in Nepal and South Africa. SSM—Ment. Health 2024, 5, 100289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, W.W.; Chui, R.C.; Chan, C.K.; Cheung, A.; Chiu, C.Y. Youth-Led Co-Creative Mental Health Training Programme for Improving Mental Wellbeing and Reducing Stigma among Adolescents in Hong Kong: Insights from A Pilot Study. Ment. Health 2024, 50, 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Weissberg, R.P.; O’Brien, M.U. What Works in School-Based Social and Emotional Learning Programs for Positive Youth Development. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2004, 591, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, R.F.; Berglund, M.L.; Ryan, J.A.M.; Lonczak, H.S.; Hawkins, J.D. Positive Youth Development in the United States: Research Findings on Evaluations of Positive Youth Development Programs. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2004, 591, 98–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gestsdóttir, S.; Lerner, R.M. Intentional self-regulation and positive youth development in early adolescence: Findings from the 4-h study of positive youth development. Dev. Psychol. 2007, 43, 508–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, P.L.; Scales, P.C.; Hamilton, S.F.; Sesma, A. Positive Youth Development: Theory, Research, and Applications. In Handbook of Child Psychology, 1st ed.; Damon, W., Lerner, R.M., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziano, F.; Mastrokoukou, S.; Monchietto, A.; Marchisio, C.; Calandri, E. The moderating role of emotional self-efficacy and gender in teacher empathy and inclusive education. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.T.P. Positive psychology 2.0: Towards a balanced interactive model of the good life. Can. Psychol./Psychol. Can. 2011, 52, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.T.P.; Arslan, G.; Bowers, V.L.; Peacock, E.J.; Kjell, O.N.E.; Ivtzan, I.; Lomas, T. Self-Transcendence as a Buffer Against COVID-19 Suffering: The Development and Validation of the Self-Transcendence Measure-B. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 648549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerner, R.M.; Alberts, A.E.; Jelicic, H.; Smith, L.M. Young People Are Resources to Be Developed: Promoting Positive Youth Development through Adult-Youth Relations and Community Assets. In Mobilizing Adults for Positive Youth Development; Clary, E.G., Rhodes, J.E., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; Volume 4, pp. 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shek, D.T. EDITORIAL: Construction of a positive youth development project in Hong Kong. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2006, 18, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shek, D.T.L.; Siu, A.M.H. “UNHAPPY” Environment for Adolescent Development in Hong Kong. J. Adolesc. Health 2019, 64, S1–S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shankar, P.; Sievers, D.; Sharma, R. Evaluating the Impact of a School-Based Youth-Led Health Education Program for Adolescent Females in Mumbai, India. Ann. Glob. Health 2020, 86, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovskaya, I. A shift towards self-transcendence: Can service learning make a difference? Horizon 2019, 27, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, P.W. Dealing with stigma through personal disclosure. In On the Stigma of Mental Illness: Practical Strategies for Research and Social Change; Corrigan, P.W., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; pp. 257–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allport, G.W. The Nature of Prejudice; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, I. A Japan–US cross-cultural study of relationships among team autonomy, organizational social capital, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2013, 37, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shek, D.T.L.; Siu, A.M.H.; Lee, T.Y. The Chinese Positive Youth Development Scale: A Validation Study. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2007, 17, 380–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, B.G. Understanding Labeling Effects in the Area of Mental Disorders: An Assessment of the Effects of Expectations of Rejection. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1987, 52, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K.D.; Bluth, K.; Tóth-Király, I.; Davidson, O.; Knox, M.C.; Williamson, Z.; Costigan, A. Development and Validation of the Self-Compassion Scale for Youth. J. Personal. Assess. 2021, 103, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennant, R.; Hiller, L.; Fishwick, R.; Platt, S.; Joseph, S.; Weich, S.; Parkinson, J.; Secker, J.; Stewart-Brown, S. The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2007, 5, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaron, J. Strengths Use and Current Knowledge Scale. In Positive Psychological Assessment: A Practical Introduction to Empirically Validated Research Tools for Measuring Wellbeing; Mental Health Commission of NSW: Sydney, Australia, 2011; pp. 25–26. Available online: https://www.nswmentalhealthcommission.com.au/sites/default/files/inline-files/workshop_4_-_dr_aaron_jarden_-_positive_psychological_assessment_workbook.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Hammer, J.H.; Parent, M.C.; Spiker, D.A. Mental Help Seeking Attitudes Scale (MHSAS): Development, reliability, validity, and comparison with the ATSPPH-SF and IASMHS-PO. J. Couns. Psychol. 2018, 65, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shek, D.T.L.; Siu, A.M.H.; Lee, T.Y.; Cheung, C.K.; Chung, R. Effectiveness of the Tier 1 Program of Project P.A.T.H.S.: Objective Outcome Evaluation Based on a Randomized Group Trial. Sci. World J. 2008, 8, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, R.C.F.; Shek, D.T.L. Life Satisfaction, Positive Youth Development, and Problem Behaviour Among Chinese Adolescents in Hong Kong. Soc. Indic. Res. 2010, 95, 455–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, R.C.F.; Shek, D.T.L. Positive Youth Development, Life Satisfaction and Problem Behaviour Among Chinese Adolescents in Hong Kong: A Replication. Soc. Indic. Res. 2012, 105, 541–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundre, D.L. Does Examinee Motivation Moderate the Relationship between Test Consequences and Test Performance? In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Montreal, QC, Canada, 19–23 April 1999; Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED432588 (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Wolf, L.F.; Smith, J.K. The Consequence of Consequence: Motivation, Anxiety, and Test Performance. Appl. Meas. Educ. 1995, 8, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundre, D.L.; Thelk, A.D. The Student Opinion Scale (SOS). A Measure of Examinee Motivation. Test Manual; Center for Assessment and Research Studies, James Madison University: Harrisonburg, VA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, P. Handbook of Psychological Testing; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ip, W.Y.; Lui, M.H.; Chien, W.T.; Lee, I.F.; Lam, L.W.; Lee, D. Promoting self-reflection in clinical practice among Chinese nursing undergraduates in Hong Kong. Contemp. Nurse 2012, 41, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, H.K.C. Student Motivation on a Diagnostic and Tracking English Language Test in Hong Kong [Institute of Education, University of London]. 2013. Available online: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10017892 (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Mora-Ríos, J.; Ortega-Ortega, M. Perceived Devaluation and Discrimination toward mental illness Scale (PDDs): Its association with sociodemographic variables and interpersonal contact in a Mexican sample. Salud Ment. 2021, 44, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sum, M.Y.; Chan, S.K.W.; Suen, Y.N.; Cheung, C.; Hui, C.L.M.; Chang, W.C.; Lee, E.H.M.; Chen, E.Y.H. The role of education level on changes in endorsement of medication treatment and perceived public stigma towards psychosis in Hong Kong: Comparison of three population-based surveys between 2009 and 2018. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Luk, T.T.; Wang, M.P.; Shen, C.; Ho, S.Y.; Viswanath, K.; Chan, S.S.C.; Lam, T.H. The reliability and validity of the Chinese Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale in the general population of Hong Kong. Qual. Life Res. 2019, 28, 2813–2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.S.; Lo, A.W.; Leung, T.K.; Chan, F.S.; Wong, A.T.; Lam, R.W.; Tsang, D.K. Translation and validation of the Chinese version of the short Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale for patients with mental illness in Hong Kong. East Asian Arch. Psychiatry 2014, 24, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, H.N.; Ho, W.S.; Habibi Asgarabad, M.; Chan, S.W.Y.; Williams, J. A Multiple Indicator Multiple Cause (MIMIC) model of the Self-Compassion Scale Youth (SCS-Y) and investigation of differential item functioning in China, Hong Kong and UK adolescents. Mindfulness 2023, 14, 1967–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindji, R.; Linley, P.A. Strengths use, self-concordance and well-being: Implications for Strengths Coaching and Coaching Psychologists. Int. Coach. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 2, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A.M.; Linley, P.A.; Maltby, J.; Kashdan, T.B.; Hurling, R. Using personal and psychological strengths leads to increases in well-being over time: A longitudinal study and the development of the strengths use questionnaire. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2011, 50, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guitard, J.; Jarden, A.; Jarden, R.; Lajoie, D. An Evaluation of the Psychometric Properties of the Temporal Satisfaction With Life Scale. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 795478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.H.; Bao, X.; Shi, L.; Wang, D. Associations between eHealth literacy, mental health-seeking attitude, and mental wellbeing among young electronic media users in China during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1139786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, L.N. Guidelines for repeated measures statistical analysis approaches with basic science research considerations. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 133, e171058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganathan, P. An Introduction to Statistics: Choosing the Correct Statistical Test. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 25, S184–S186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics; Sage Publications Limited: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Proudfoot, K. Inductive/Deductive Hybrid Thematic Analysis in Mixed Methods Research. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2023, 17, 308–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groenwold, R.H.H.; Goeman, J.J.; Cessie, S.L.; Dekkers, O.M. Multiple testing: When is many too much? Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2021, 184, E11–E14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shek, D.T.L.; Leung, J.T.Y. Developing social competence in a subject on leadership and intrapersonal development. Int. J. Disabil. Hum. Dev. 2016, 15, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Prette, Z.A.P.; Del Prette, A. Programs and the Experiential Method. In Social Competence and Social Skills; Del Prette, Z.A.P., Del Prette, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonert-Reichl, K.A.; Lawlor, M.S. The Effects of a Mindfulness-Based Education Program on Pre- and Early Adolescents’ Well-Being and Social and Emotional Competence. Mindfulness 2010, 1, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawardena, H.; Voukelatos, A.; Nair, S.; Cross, S.; Hickie, I.B. Efficacy and Effectiveness of Universal School-Based Wellbeing Interventions in Australia: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, B.; Woodcock, S.; Dudley, D. Developing Wellbeing Through a Randomised Controlled Trial of a Martial Arts Based Intervention: An Alternative to the Anti-Bullying Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 16, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, B.; Woodcock, S.; Dudley, D. Well-being warriors: A randomized controlled trial examining the effects of martial arts training on secondary students’ resilience. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 91, 1369–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, S.; Kemp, L.; Bunde-Birouste, A.; MacKenzie, J.; Evers, C.; Shwe, T.A. “We wouldn’t of made friends if we didn’t come to Football United”: The impacts of a football program on young people’s peer, prosocial and cross-cultural relationships. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, K.M.; Middleton, T.; Kemps, E.; Chen, J. A pilot investigation of universal school-based prevention programs for anxiety and depression symptomology in children: A randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 76, 1193–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, M.; Knight, B.A.; Hasking, P.; Withyman, C.; Dawkins, J. Building resilience in regional youth: Impacts of a universal mental health promotion programme. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2018, 27, 1044–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomyn, J.D.; Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M.; Richardson, B.; Colla, L. A Comprehensive Evaluation of a Universal School-Based Depression Prevention Program for Adolescents. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2016, 44, 1621–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Midford, R.; Cahill, H.; Geng, G.; Leckning, B.; Robinson, G.; Te Ava, A. Social and emotional education with Australian Year 7 and 8 middle school students: A pilot study. Health Educ. J. 2017, 76, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, C.; Misurell, J.; Kranzler, A.; Liotta, L.; Gillham, J. Resilience Interventions for Youth. In The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Positive Psychological Interventions, 1st ed.; Parks, A.C., Schueller, S.M., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 310–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dray, J.; Bowman, J.; Freund, M.; Campbell, E.; Wolfenden, L.; Hodder, R.K.; Wiggers, J. Improving adolescent mental health and resilience through a resilience-based intervention in schools: Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2014, 15, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bluth, K.; Clepper-Faith, M. Self-Compassion in Adolescence. In Handbook of Self-Compassion; Finlay-Jones, A., Bluth, K., Neff, K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K.D. Self-Compassion: Theory, Method, Research, and Intervention. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2023, 74, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biggs, A.; Brough, P.; Drummond, S. Lazarus and Folkman’s Psychological Stress and Coping Theory. In The Handbook of Stress and Health, 1st ed.; Cooper, C.L., Quick, J.C., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dishon, N.; Oldmeadow, J.A.; Kaufman, J. Trait self-awareness predicts perceptions of choice meaningfulness in a decision-making task. BMC Res. Notes 2018, 11, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dierdorff, E.C.; Fisher, D.M.; Rubin, R.S. The Power of Percipience: Consequences of Self-Awareness in Teams on Team-Level Functioning and Performance. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 2891–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffens, N.K.; Wolyniec, N.; Okimoto, T.G.; Mols, F.; Haslam, S.A.; Kay, A.A. Knowing me, knowing us: Personal and collective self-awareness enhances authentic leadership and leader endorsement. Leadersh. Q. 2021, 32, 101498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoshani, A.; Steinmetz, S. Positive Psychology at School: A School-Based Intervention to Promote Adolescents’ Mental Health and Well-Being. J. Happiness Stud. 2014, 15, 1289–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, L.; Williams, I.R.; Olsson, C.A.; Allen, N.B. Promoting Adolescent Health and Well-Being Through Outdoor Youth Programs: Results From a Multisite Australian Study. J. Outdoor Recreat. Educ. Leadersh. 2018, 10, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gander, F.; Proyer, R.T.; Ruch, W. Positive Psychology Interventions Addressing Pleasure, Engagement, Meaning, Positive Relationships, and Accomplishment Increase Well-Being and Ameliorate Depressive Symptoms: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Online Study. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gander, F.; Proyer, R.T.; Ruch, W. The Subjective Assessment of Accomplishment and Positive Relationships: Initial Validation and Correlative and Experimental Evidence for Their Association with Well-Being. J. Happiness Stud. 2017, 18, 743–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, G. Psychological Well-Being and Mental Health in Youth: Technical Adequacy of the Comprehensive Inventory of Thriving. Children 2023, 10, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, L. Correlations Between Mindset and Participation in Everyday Activities Among Healthy Adolescents. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2023, 77, 7706205080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, R.; Brooks, S.; Goldstein, S. The Power of Mindsets: Nurturing Engagement, Motivation, and Resilience in Students. In Handbook of Research on Student Engagement; Christenson, S.L., Reschly, A.L., Wylie, C., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 541–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, E.Y.; Tse, T.T. Effect of human library intervention on mental health literacy: A multigroup pretest–posttest study. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortune, D.; Leighton, J. Mental Illness as a Valued Identity: How a Leisure Initiative Promoting Connection and Understanding Sets the Stage for Inclusion. Leis. Sci. 2024, 46, 1031–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.K.Y.; Anderson, J.K.; Burn, A. Review: School-based interventions to improve mental health literacy and reduce mental health stigma—A systematic review. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2023, 28, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.I.; Leventhal, B.L.; Nielsen, B.N.; Hinshaw, S.P. Reducing mental-illness stigma via high school clubs: A matched-pair, cluster-randomized trial. Stigma Health 2020, 5, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aseltine, R.H.; DeMartino, R. An Outcome Evaluation of the SOS Suicide Prevention Program. Am. J. Public Health 2004, 94, 446–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisholm, K.; Patterson, P.; Torgerson, C.; Turner, E.; Jenkinson, D.; Birchwood, M. Impact of contact on adolescents’ mental health literacy and stigma: The SchoolSpace cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e009435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingman, A.; Hochdorf, Z. Coping with distress and self harm: The impact of a primary prevention program among adolescents. J. Adolesc. 1993, 16, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milin, R.; Kutcher, S.; Lewis, S.P.; Walker, S.; Wei, Y.; Ferrill, N.; Armstrong, M.A. Impact of a Mental Health Curriculum on Knowledge and Stigma Among High School Students: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2016, 55, 383–391.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.J.; Dang, H.-M.; Bui, D.; Phoeun, B.; Weiss, B. Experimental Evaluation of a School-Based Mental Health Literacy Program in two Southeast Asian Nations. Sch. Ment. Health 2020, 12, 716–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.; Shryane, N.; Byrne, R.; Morrison, A.P. A mental health promotion approach to reducing discrimination about psychosis in teenagers. Psychosis 2011, 3, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, S.D. Developmental Predictors of Adolescent Mental Health Stigma and a Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial of ‘Ending the Silence’ in New York City [City University of New York]. 2020. Available online: http://academicworks.cuny.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4990&context=gc_etds (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- DeLuca, J.S.; Tang, J.; Zoubaa, S.; Dial, B.; Yanos, P.T. Reducing stigma in high school students: A cluster randomized controlled trial of the National Alliance on Mental Illness’ Ending the Silence intervention. Stigma Health 2021, 6, 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mara, L.; Akhtar-Danesh, N.; Browne, G.; Mueller, D.; Grypstra, L.; Vrkljan, C.; Powell, M. Does Youth Net Decrease Mental Illness Stigma in High School Students? Can. J. Community Ment. Health 2013, 32, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.E.; Wood, L.J. Drumming to a New Beat: A Group Therapeutic Drumming and Talking Intervention to Improve Mental Health and Behaviour of Disadvantaged Adolescent Boys. Child. Aust. 2017, 42, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, S.; Sawyer, M.; Sheffield, J.; Patton, G.; Bond, L.; Graetz, B.; Kay, D. Does the Absence of a Supportive Family Environment Influence the Outcome of a Universal Intervention for the Prevention of Depression? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 5113–5132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osborne, M.S.; McPherson, G.E.; Faulkner, R.; Davidson, J.W.; Barrett, M.S. Exploring the academic and psychosocial impact of El Sistema-inspired music programs within two low socio-economic schools. Music Educ. Res. 2016, 18, 156–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burckhardt, R.; Manicavasagar, V.; Batterham, P.J.; Hadzi-Pavlovic, D. A randomized controlled trial of strong minds: A school-based mental health program combining acceptance and commitment therapy and positive psychology. J. Sch. Psychol. 2016, 57, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colla, L.; Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M.; Tomyn, A.J.; Richardson, B.; Tomyn, J.D. Use of weekly assessment data to enhance evaluation of a subjective wellbeing intervention. Qual. Life Res. 2016, 25, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burckhardt, R.; Manicavasagar, V.; Batterham, P.J.; Hadzi-Pavlovic, D.; Shand, F. Acceptance and commitment therapy universal prevention program for adolescents: A feasibility study. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2017, 11, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, K.; Williams, C. Universal, school-based interventions to promote mental and emotional well-being: What is being done in the UK and does it work? A systematic review. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e022560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuyken, W.; Weare, K.; Ukoumunne, O.C.; Vicary, R.; Motton, N.; Burnett, R.; Cullen, C.; Hennelly, S.; Huppert, F. Effectiveness of the Mindfulness in Schools Programme: Non-randomised controlled feasibility study. Br. J. Psychiatry 2013, 203, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyman, P.A.; Brown, C.H.; LoMurray, M.; Schmeelk-Cone, K.; Petrova, M.; Yu, Q.; Walsh, E.; Tu, X.; Wang, W. An Outcome Evaluation of the Sources of Strength Suicide Prevention Program Delivered by Adolescent Peer Leaders in High Schools. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 1653–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Session | Topic | Goals | Contents |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction to Mental Health |

|

|

| 2 | Recovery |

|

|

| |||

| 3 | Resilience |

|

|

| |||

| 4 | Self-Compassion |

|

|

| |||

| 5 | Listening |

|

|

| |||

| 6 | Personal Strength |

|

|

|

| ||

| |||

| 7 | Community Resources |

|

|

| 8 | Use Social Media to Promote Mental Health |

|

|

| |||

|

|

| Demographic | Mean | SD | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 16.05 | 0.953 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 37 | 46.3 | ||

| Female | 43 | 53.8 | ||

| Secondary | ||||

| Secondary 3 | 11 | 13.8 | ||

| Secondary 4 | 44 | 55.0 | ||

| Secondary 5 | 25 | 31.3 | ||

| Monthly Household Income | ||||

| HKD 0–10,000 | 3 | 3.8 | ||

| HKD 10,001–20,000 | 9 | 11.3 | ||

| HKD 20,001–30,000 | 5 | 6.3 | ||

| HKD 30,001–40,000 | 2 | 2.5 | ||

| HKD 40,001–50,000 | 4 | 5.0 | ||

| HKD 50,001–60,000 | 1 | 1.3 | ||

| HKD 60,001–70,000 | 1 | 1.3 | ||

| HKD 70,001–80,000 | 0 | 0 | ||

| HKD 80,001 or above | 6 | 7.5 | ||

| Not Sure | 49 | 61.3 | ||

| Residential Housing Type | ||||

| Public Housing | 24 | 30.0 | ||

| Home Ownership Scheme (HOS) | 12 | 15.0 | ||

| Private | 38 | 47.5 | ||

| Others | 6 | 7.5 | ||

| Location of School | ||||

| Hong Kong | 19 | 23.8 | ||

| Kowloon | 29 | 36.3 | ||

| New Territories | 32 | 40.0 | ||

| Organization | ||||

| CYS | 32 | 40.0 | ||

| TWGHs | 13 | 16.3 | ||

| SKHWC | 24 | 30.0 | ||

| SJS | 11 | 13.8 | ||

| Scales | Baseline | Post-Training | Implementation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | df | Sig. | Statistic | df | Sig. | Statistic | df | Sig. | |

| Social Competence Scale | 0.117 | 80 | 0.008 | 0.132 | 80 | 0.001 | 0.116 | 80 | 0.010 |

| Emotional Competence | 0.086 | 80 | 0.200 * | 0.103 | 80 | 0.035 | 0.059 | 80 | 0.200 * |

| Cognitive Competence | 0.066 | 80 | 0.200 * | 0.095 | 80 | 0.070 | 0.175 | 80 | <0.001 |

| Self-Efficacy Competence | 0.068 | 80 | 0.200 * | 0.089 | 80 | 0.177 | 0.149 | 80 | <0.001 |

| Resilience | 0.064 | 80 | 0.200 * | 0.096 | 80 | 0.068 | 0.101 | 80 | 0.043 |

| Motivational Competence | 0.125 | 80 | 0.003 | 0.108 | 80 | 0.022 | 0.160 | 80 | <0.001 |

| Sense of Mastery | 0.123 | 80 | 0.005 | 0.153 | 80 | <0.001 | 0.146 | 80 | <0.001 |

| Perceived Devaluation-Discrimination | 0.094 | 80 | 0.076 | 0.205 | 80 | <0.001 | 0.185 | 80 | <0.001 |

| Mental Well-being | 0.067 | 80 | 0.200 * | 0.109 | 80 | 0.020 | 0.104 | 80 | 0.033 |

| Self-Compassion | 0.145 | 80 | <0.001 | 0.139 | 80 | 0.001 | 0.160 | 80 | <0.001 |

| Awareness of Personal Strength | 0.117 | 80 | 0.008 | 0.111 | 80 | 0.016 | 0.115 | 80 | 0.011 |

| Positive Attitudes towards Seeking Services | 0.068 | 80 | 0.200 * | 0.167 | 80 | <0.001 | 0.114 | 80 | 0.012 |

| Scales | Baseline MDN (T1) | Post-Training MDN (T2) | Implementation MDN (T3) | Friedman Test χ2 | Benjamini–Hochberg Adjusted p | Post Hoc Pairwise Comparison * | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pairwise Comparison | r (Effect Size) | Bonferroni Correction Adjusted p | ||||||

| Social Competence | 28 | 30 | 30 | 20.216 | <0.001 | T1–T2 | 0.41 | 0.001 |

| T1–T3 | 0.38 | 0.002 | ||||||

| Cognitive Competence | 27 | 29 | 29 | 13.251 | 0.003 | T1–T2 | 0.33 | 0.009 |

| T1–T3 | 0.33 | 0.009 | ||||||

| Emotional Competence | 24 | 26 | 26 | 9.017 | 0.022 | T1–T3 | 0.30 | 0.024 |

| Resilience | 26.5 | 29 | 29 | 16.050 | 0.001 | T1–T2 | 0.41 | 0.001 |

| T1–T3 | 0.30 | 0.024 | ||||||

| Self-Compassion | 48 | 48 | 48.5 | 1.199 | 0.732 | |||

| Self-Efficacy Competence | 29 | 30.5 | 31 | 5.062 | 0.136 | |||

| Sense of Mastery | 18 | 19 | 19.5 | 16.572 | 0.002 | T1–T2 | 0.31 | 0.015 |

| T1–T3 | 0.40 | 0.001 | ||||||

| Awareness of Personal Strength | 50 | 51 | 51 | 0.164 | 0.921 | |||

| Motivational Competence | 37 | 38 | 37 | 0.433 | 0.967 | |||

| Mental Well-being | 24 | 23 | 26 | 14.676 | 0.002 | T1–T2 | 0.39 | 0.002 |

| T2–T3 | 0.30 | 0.022 | ||||||

| Positive Attitudes towards Seeking Services | 9.5 | 8 | 9 | 0.351 | 0.915 | |||

| Perceived Devaluation-Discrimination | 38 | 36 | 37 | 4.252 | 0.179 | |||

| Item | Post-Training Phase | Post-Implementation Phase | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| The programme has helped me understand the importance of recognizing and being aware of mental health. | 4.16 | 0.834 | 4.21 | 0.833 |

| The programme has helped me understand the importance of promoting community awareness of mental health. | 4.12 | 0.880 | 4.24 | 0.757 |

| The programme has helped me understand the emotional needs and feelings of those around me, making me more empathetic towards them. | 4.10 | 0.872 | 4.28 | 0.79 |

| The programme has helped me better understand how to seek suitable resources and methods to support individuals in need of mental health support, including myself. | 4.05 | 0.867 | 4.24 | 0.757 |

| Overall, I feel that the programme has been helpful to me. | 4.19 | 0.907 | 4.28 | 0.854 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chung, W.-C.; Jiang, F.; Fok, Y.L.B.; Chiu, C.Y.; Yuen, W.W.Y.; Fung, J.W.-F.; Tang, A.C.Y.; Li, P.F.J.; Chui, R.C.-F.; Chan, C.-K. Evaluating the Effectiveness of a School-Based Mental Health Training Programme: The Transformative, Resilient, Youth-Led (TRY) Gym. Healthcare 2026, 14, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010009

Chung W-C, Jiang F, Fok YLB, Chiu CY, Yuen WWY, Fung JW-F, Tang ACY, Li PFJ, Chui RC-F, Chan C-K. Evaluating the Effectiveness of a School-Based Mental Health Training Programme: The Transformative, Resilient, Youth-Led (TRY) Gym. Healthcare. 2026; 14(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleChung, Wai-Chung, Fan Jiang, Yin Ling Beryl Fok, Cheung Ying Chiu, Winnie Wing Yan Yuen, Josephine Wing-Fun Fung, Anson Chui Yan Tang, Po Fai Jonah Li, Raymond Chi-Fai Chui, and Chi-Keung Chan. 2026. "Evaluating the Effectiveness of a School-Based Mental Health Training Programme: The Transformative, Resilient, Youth-Led (TRY) Gym" Healthcare 14, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010009

APA StyleChung, W.-C., Jiang, F., Fok, Y. L. B., Chiu, C. Y., Yuen, W. W. Y., Fung, J. W.-F., Tang, A. C. Y., Li, P. F. J., Chui, R. C.-F., & Chan, C.-K. (2026). Evaluating the Effectiveness of a School-Based Mental Health Training Programme: The Transformative, Resilient, Youth-Led (TRY) Gym. Healthcare, 14(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010009