The Path from Depressive Symptoms to Subjective Well-Being Among Korean Young Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Mediating Roles of Housing Satisfaction, Social Capital, Future Achievement Readiness, and Occupational Hazards

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Global and National Context

1.2. Literature Review

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Measurements

2.2.1. Dependent Variable

2.2.2. Independent Variable

2.2.3. Mediating Variables

2.2.4. Control Variables

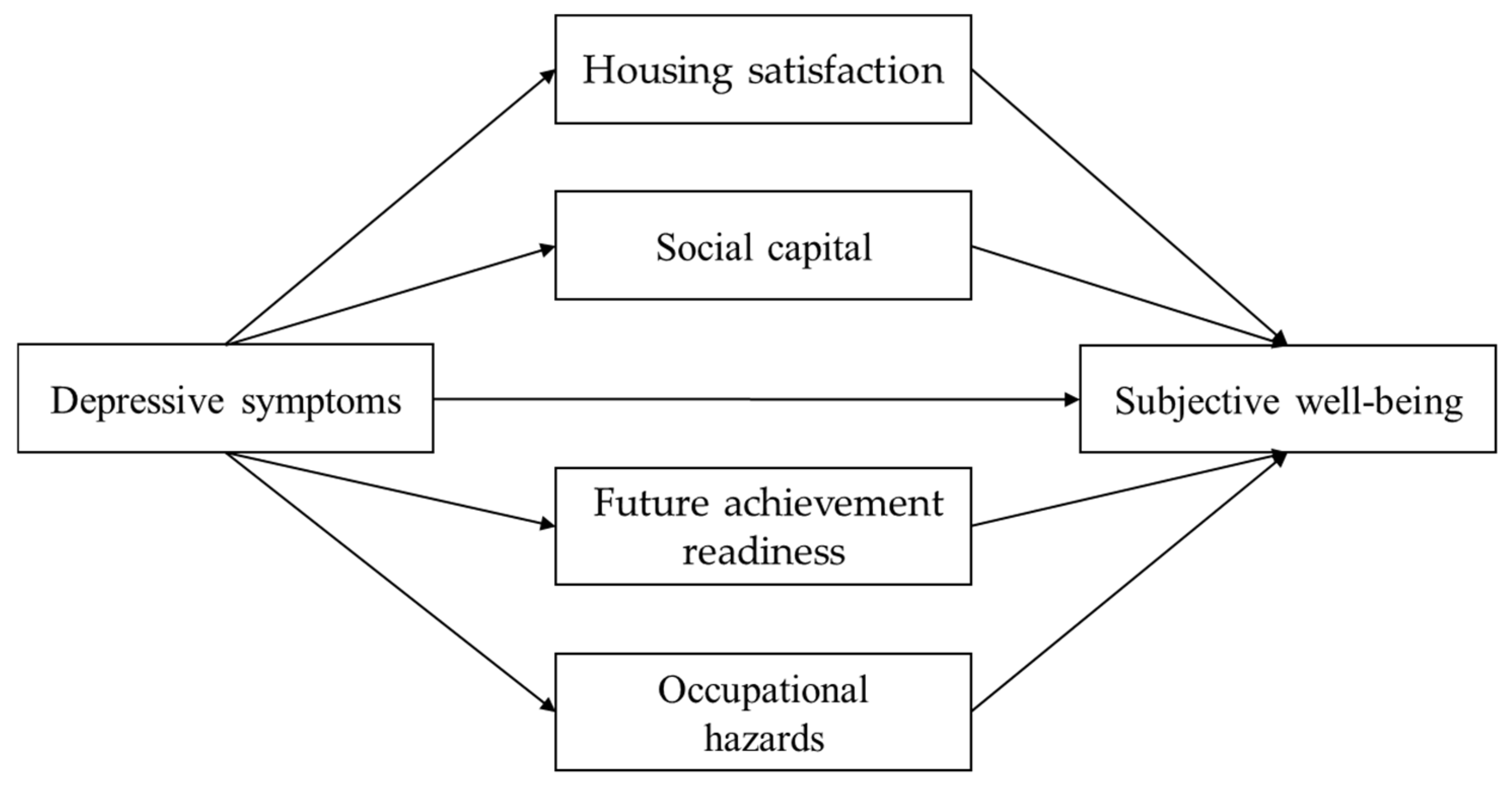

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Factors Affecting Subjective Well-Being

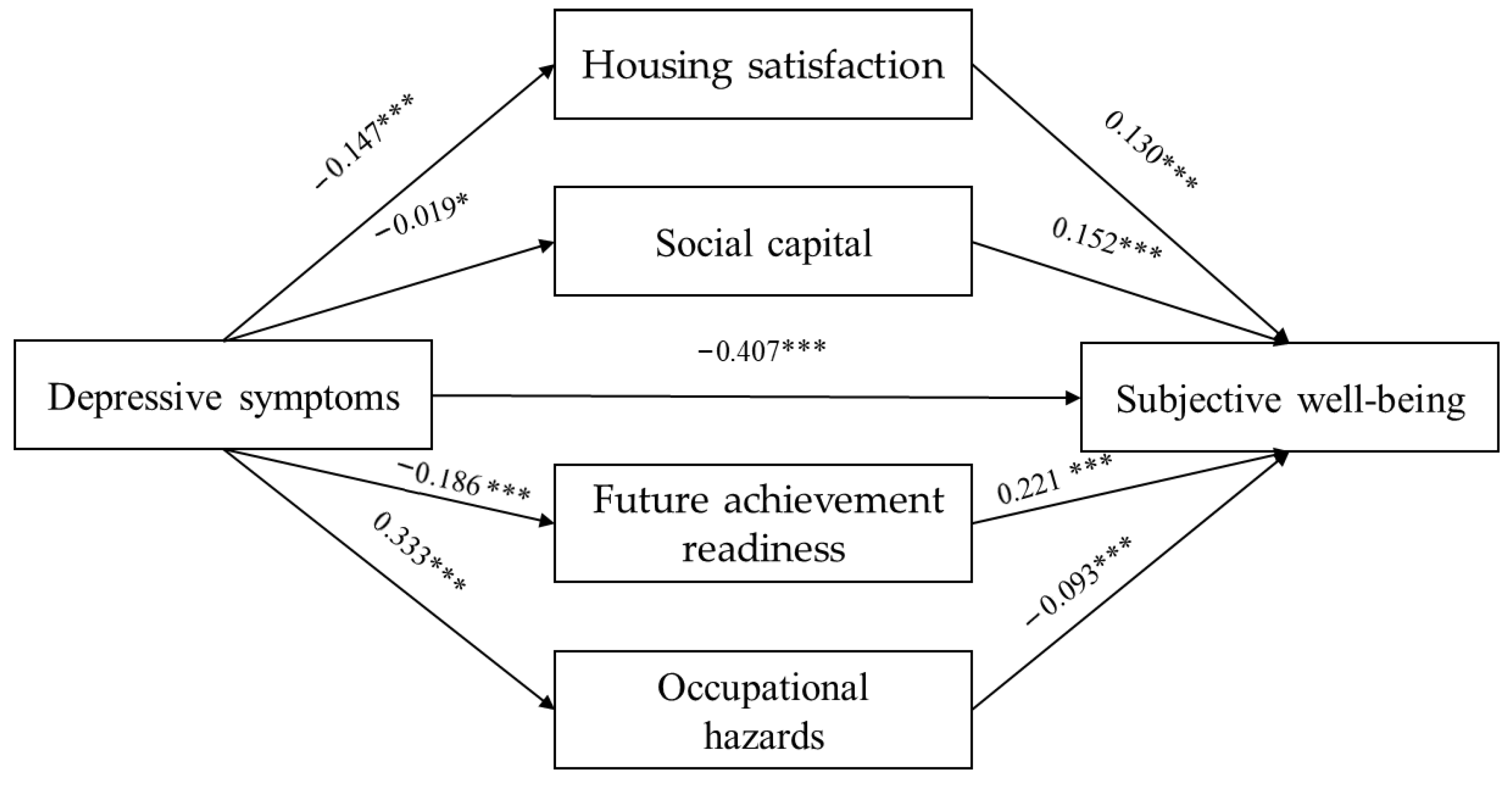

3.3. Mediation Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jensen, L.A.; Arnett, J.J. Going global: New pathways for adolescents and emerging adults in a changing world. J. Soc. Issues 2012, 68, 473–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.-J.; Kim, M.-G.; Kim, T.-A.; Kim, D.-J.; Kim, S.-A.; Lee, W.-J.; Lee, H.-J.; Lim, D.-Y.; Hap, S.-Y.; Ryu, J.-A.; et al. Study on the Future Directions for the Korean Youth Life Survey; Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs (KIHASA): Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2021. Available online: https://www.opm.go.kr/opm/info/policies.do?mode=view&articleNo=140295 (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Birditt, K.S.; Turkelson, A.; Fingerman, K.L.; Polenick, C.A.; Oya, A. Age differences in stress, life changes, and social ties during the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for psychological well-being. Gerontologist 2021, 61, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, K.V.; Jones-Harrell, C.; Fan, Y.; Ramaswami, A.; Orlove, B.; Botchwey, N. Understanding subjective well-being: Perspectives from psychology and public health. Public Health Rev. 2020, 41, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Page, A. Stability and instability of subjective well-being in the transition from adolescence to young adulthood: Longitudinal evidence from 20991 young Australians. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, I.M.; Seland, I. Conceptualizing well-being in youth: The potential of youth clubs. YOUNG 2021, 29, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathentamo, Q.; Lawana, N.; Hlafa, B. Interrelationship between subjective wellbeing and health. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forum, E.Y. The Universal Recognition of the Rights of Young People; European Youth Forum: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Government Legislation. Framework Act on Youth; Ministry of Government Legislation: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2022. Available online: https://elaw.klri.re.kr/eng_service/lawView.do?hseq=32480&lang=ENG (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs. A Study on the Lives of Young Adults and Policy Support Measures; Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2020.

- Brito, A.D.; Soares, A.B. Well-being, character strengths, and depression in emerging adults. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1238105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ya, Z.; Xiang-Ping, L.; Yang, S.; Li-Wen, R. Negative biases or positivity lacks? The explanation of positive psychology on depression. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 18, 590–597. [Google Scholar]

- Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service. Analysis of Treatment Trends for Depression and Anxiety Disorders over the Past Five Years (2017–2021); Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service: Wonju, Republic of Korea, 2022. Available online: https://www.hira.or.kr/bbsDummy.do?pgmid=HIRAA020041000100&brdScnBltNo=4&brdBltNo=10627 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Slimmen, S.; Timmermans, O.; Lechner, L.; Oenema, A. The direct and indirect effects of social environmental factors on student mental wellbeing at different socio-ecological levels: A longitudinal perspective. Wellbeing Space Soc. 2025, 9, 100294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.I.; Jeon, S.B.; Goh, T.K. Integrated indices of the quality of life for the young adult generation in Korea. Soc. Sci. Stud. 2019, 27, 88–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. The recent rise in youth unemployment rate in Korea: A flow decomposition Analysis. Korean Econ. Rev. 2022, 38, 445–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, J.A.; Schutte, N.S. The relationships between the hope dimensions of agency thinking and pathways thinking with depression and anxiety: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Appl. Posit. Psychol. 2023, 8, 211–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.; Lee, H.S. A Study on the effects of life satisfaction on social capital: An analysis of mediating effect of settlement consciousness and self-efficacy. Korean J. Public Manag. 2019, 33, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R.J.; Samek, D.R.; Wilson, S.; Iacono, W.G.; McGue, M. Close relationships and depression: A developmental cascade approach. Dev. Psychopathol. 2019, 31, 1451–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, D.; Jeong, K.H.; Kim, Y.; Li, R. The impact of housing satisfaction on subjective well-being in young adult single-person households—The mediating effect of depression-. J. Korea Acad.-Ind. Coop. Soc. 2025, 26, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Jung, S.; Jun, H.-J. The change in the influence of environmental factors on depression by the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Korean Reg. Sci. Assoc. 2024, 40, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beevers, C.G.; Mullarkey, M.C.; Dainer-Best, J.; Stewart, R.A.; Labrada, J.; Allen, J.J.; McGeary, J.E.; Shumake, J. Association between negative cognitive bias and depression: A symptom-level approach. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2019, 128, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sønderlund, A.L.; Morton, T.A.; Ryan, M.K. Multiple Group membership and well-Being: Is there always strength in numbers? Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer-Gembeck, M.J.; Skinner, E.A.; Scott, R.A.; Ryan, K.M.; Hawes, T.; Gardner, A.A.; Duffy, A.L. Parental support and adolescents’ coping with academic stressors: A longitudinal study of parents’ influence beyond academic pressure and achievement. J. Youth Adolesc. 2023, 52, 2464–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Yim, D.; Kang, M. Precariousness and happiness of South Korean young adults: The mediating effects of uncertainty and disempowerment. Korea Soc. Policy Rev. 2017, 24, 87–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, N.; Liu, Y.; Yu, S.; Xia, B.; Cong, W. Examining the role of psychological symptoms and safety climate in shaping safety behaviors among construction workers. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T. Depression: Clinical, Experimental, and Theoretical Aspects; Haper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Alloy, L.B.; Abramson, L.Y. Judgment of contingency in depressed and nondepressed students: Sadder but wiser? J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 1979, 108, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs. 2022 Korean Youth Well-Being Survey; KIHASA: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2023. Available online: https://www.opm.go.kr/opm/info/policies.do?mode=view&articleNo=153207 (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Yi, Y.-S. A multifaceted perspective exploratory study of affecting factors on subjective well-being—Focused on level of housing income and community. J. Korean Off. Stat. 2019, 26–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.-J.; Choi, H.-R.; Choi, J.-H.; Kim, K.-W.; Hong, J.-P. Reliability and validity of the Korean version of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Anxiety Mood 2010, 6, 119–124. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K. The impact of extended unemployment on subjective well-being among youth: Mediating effects of earnings, social capital, and depression. Health Soc. Welf. Rev. 2024, 44, 164–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazziotta, M.; Pareto, A. Use and misuse of PCA for measuring well-being. Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 142, 451–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliem, S.; Sachser, C.; Lohmann, A.; Baier, D.; Brähler, E.; Gündel, H.; Fegert, J.M. Psychometric evaluation and community norms of the PHQ-9, based on a representative German sample. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1483782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani Wigley, I.C.; Nazzari, S.; Pastore, M.; Provenzi, L.; Barello, S. The contribution of environmental sensitivity and connectedness to nature to mental health: Does nature view count? J. Environ. Psychol. 2025, 102, 102541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Kim, K. Is public rental housing a stepping stone for young adults’ housing: Effect of rental housing type on the intention to achieve homeownership and the mediation effect of residential satisfaction. Korean Assoc. Hous. Policy Stud. 2023, 31, 43–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, C.; Park, S.; Lee, Y.; Lee, H. Young single-person households’ housing situation and housing expectation according to subjectively assessed income levels of themselves and their parents. Korean J. Hum. Ecol. 2020, 29, 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, Z. Community participation and subjective wellbeing: Mediating roles of basic psychological needs among Chinese retirees. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 743897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Zhang, L.; Shi, W. Trait depression and subjective well-being: The chain mediating role of community feeling and self-compassion. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, C.; Davis, K.; Charmaraman, L.; Konrath, S.; Slovak, P.; Weinstein, E.; Yarosh, L. Digital life and youth well-being, social connectedness, empathy, and narcissism. Pediatrics 2017, 140, S71–S75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.Y.; Park, M.; Choi, G. Society with Class Barriers, Characteristics and Problems of the Youth and Inequalities; The Seoul Institute: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, T.; Lee, J. Being born with a wooden spoon cannot guarantee a golden future? Korean J. Econ. Stud. 2022, 70, 27–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thielen, K.; Nygaard, E.; Andersen, I.; Diderichsen, F. Employment consequences of depressive symptoms and work demands individually and combined. Eur. J. Public Health 2013, 24, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGorry, P.D.; Mei, C.; Chanen, A.; Hodges, C.; Alvarez-Jimenez, M.; Killackey, E. Designing and scaling up integrated youth mental health care. World Psychiatry 2022, 21, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Categories | N (%) or M ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 7171 (47.90%) |

| Female | 7795 (52.10%) | |

| Age | 19–24 years | 7195 (48.08%) |

| 25–29 years | 4549 (30.40%) | |

| 30–34 years | 3222 (21.53%) | |

| Employment status | Unemployed | 5317 (35.53%) |

| Employed | 9649 (64.47%) | |

| Education level | High school or below | 2084 (13.92%) |

| Attending or on leave from university/college | 4734 (31.63%) | |

| Graduate or above | 8148 (54.44%) | |

| Depressive symptoms | Normal | 11,848 (79.2%) |

| Mild depressive symptoms | 2253 (15.1%) | |

| Moderate depressive symptoms | 748 (5.0%) | |

| Severe depressive symptoms | 117 (0.8%) | |

| Annual income (KRW 0–35,000) | 1917.26 ± 1784.01 | |

| Perceived health (1–5) | 3.6 ± 0.79 | |

| Housing satisfaction (0–48) | 24.04 ± 4.61 | |

| Social capital (0–1) | 0.38 ± 0.2 | |

| Future achievement readiness (6–24) | 16.06 ± 2.36 | |

| Occupational hazards (6–30) | 10.11 ± 4.71 | |

| Subjective well-being (0–10) | 6.85 ± 1.74 | |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B | SE (B) | β | t | B | SE (B) | β | t |

| Sex (male) | 0.16 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 4.82 *** | 0.19 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 6.32 *** |

| Age | −0.11 | 0.02 | −0.05 | −4.63 *** | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.01 | −1.04 |

| Employment status | 0.19 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 3.19 *** | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 2.90 * |

| Education level | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 4.94 *** | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.01 | −1.25 |

| Income | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 7.50 *** | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 6.59 *** |

| Perceived health | 0.34 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 16.97 *** | ||||

| Depressive symptoms | −0.12 | 0.00 | −0.27 | −28.77 *** | ||||

| Future achievement readiness | 0.15 | 0.01 | 0.21 | 23.95 *** | ||||

| Social capital | 1.23 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 16.68 *** | ||||

| Housing satisfaction | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 14.30 *** | ||||

| Occupational hazards | −0.03 | 0.00 | −0.09 | −10.30 *** | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.12 | 0.31 | ||||||

| F | 238.37 *** | 106.04 *** | ||||||

| Durbin-Watson | 1.91 | 1.94 | ||||||

| B | SE (B) | t | β | F(R2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Housing satisfaction | Depressive symptoms | −0.175 | 0.010 | −15.210 | −0.150 | 231.29 *** (0.02) |

| Social capital | Depressive symptoms | 0.001 | 0.001 | 1.974 | 0.020 | 3.9 * (0. 01) |

| Future achievement readiness | Depressive symptoms | −0.114 | 0.006 | −19.608 | −0.190 | 384.49 *** (0.04) |

| Occupational hazards | Depressive symptoms | 0.404 | 0.011 | 36.323 | 0.333 | 1319.37 *** (0.11) |

| Subjective well-being | Depressive symptoms | −0.144 | 0.004 | −35.798 | −0.318 | 845.84 *** (0.29) |

| Housing satisfaction | 0.049 | 0.003 | 15.393 | 0.130 | ||

| Social capital | 1.347 | 0.075 | 18.032 | 0.152 | ||

| Future achievement readiness | 0.165 | 0.006 | 25.567 | 0.221 | ||

| Occupational hazards | −0.035 | 0.003 | −10.592 | −0.093 | ||

| Subjective well-being | Depressive symptoms | −0.184 | 0.004 | −45.700 | −0.407 | 2088.46 *** (0.17) |

| Path | Coeff | SE | LLCI | ULCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | −0.184 | 0.004 | −0.192 | −0.176 | |

| Direct effect | −0.144 | 0.004 | −0.152 | −0.136 | |

| Indirect effect | Total | −0.040 | 0.003 | −0.045 | −0.035 |

| X→M1→Y | −0.009 | 0.001 | −0.010 | −0.007 | |

| X→M2→Y | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.003 | |

| X→M3→Y | −0.019 | 0.001 | −0.022 | −0.016 | |

| X→M4→Y | −0.014 | 0.002 | −0.017 | −0.011 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kwon, M.; Cho, M. The Path from Depressive Symptoms to Subjective Well-Being Among Korean Young Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Mediating Roles of Housing Satisfaction, Social Capital, Future Achievement Readiness, and Occupational Hazards. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3189. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243189

Kwon M, Cho M. The Path from Depressive Symptoms to Subjective Well-Being Among Korean Young Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Mediating Roles of Housing Satisfaction, Social Capital, Future Achievement Readiness, and Occupational Hazards. Healthcare. 2025; 13(24):3189. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243189

Chicago/Turabian StyleKwon, Miyoung, and Myongsun Cho. 2025. "The Path from Depressive Symptoms to Subjective Well-Being Among Korean Young Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Mediating Roles of Housing Satisfaction, Social Capital, Future Achievement Readiness, and Occupational Hazards" Healthcare 13, no. 24: 3189. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243189

APA StyleKwon, M., & Cho, M. (2025). The Path from Depressive Symptoms to Subjective Well-Being Among Korean Young Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Mediating Roles of Housing Satisfaction, Social Capital, Future Achievement Readiness, and Occupational Hazards. Healthcare, 13(24), 3189. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243189