Physical Activity Patterns and Behavioral Resilience Among Foggia University Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Public Health Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

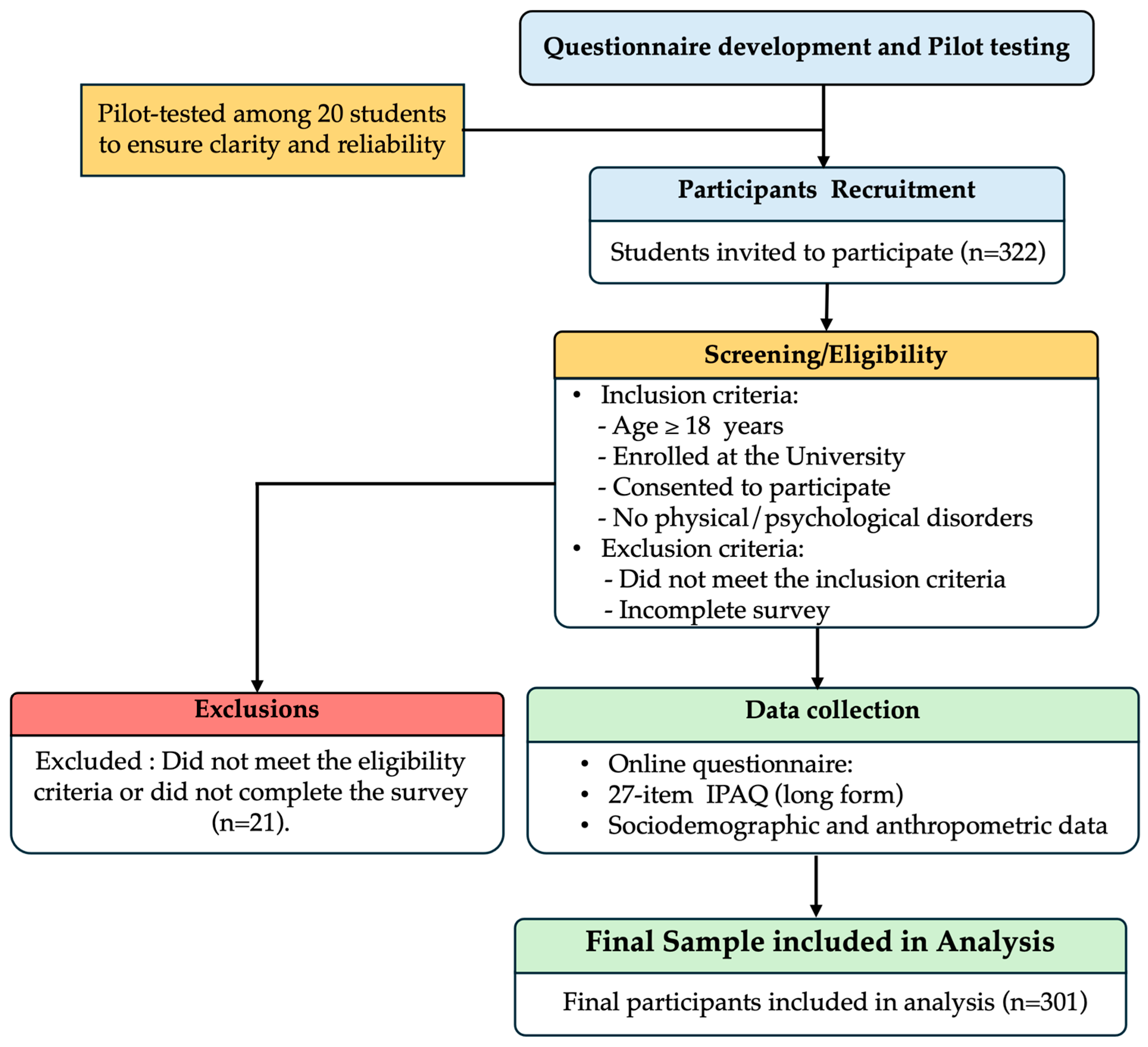

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Settings

2.2. Participants

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria for the Participants

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria for the Participants

2.3. Study Instrument

2.4. Outcome Measure and Data Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Study Population

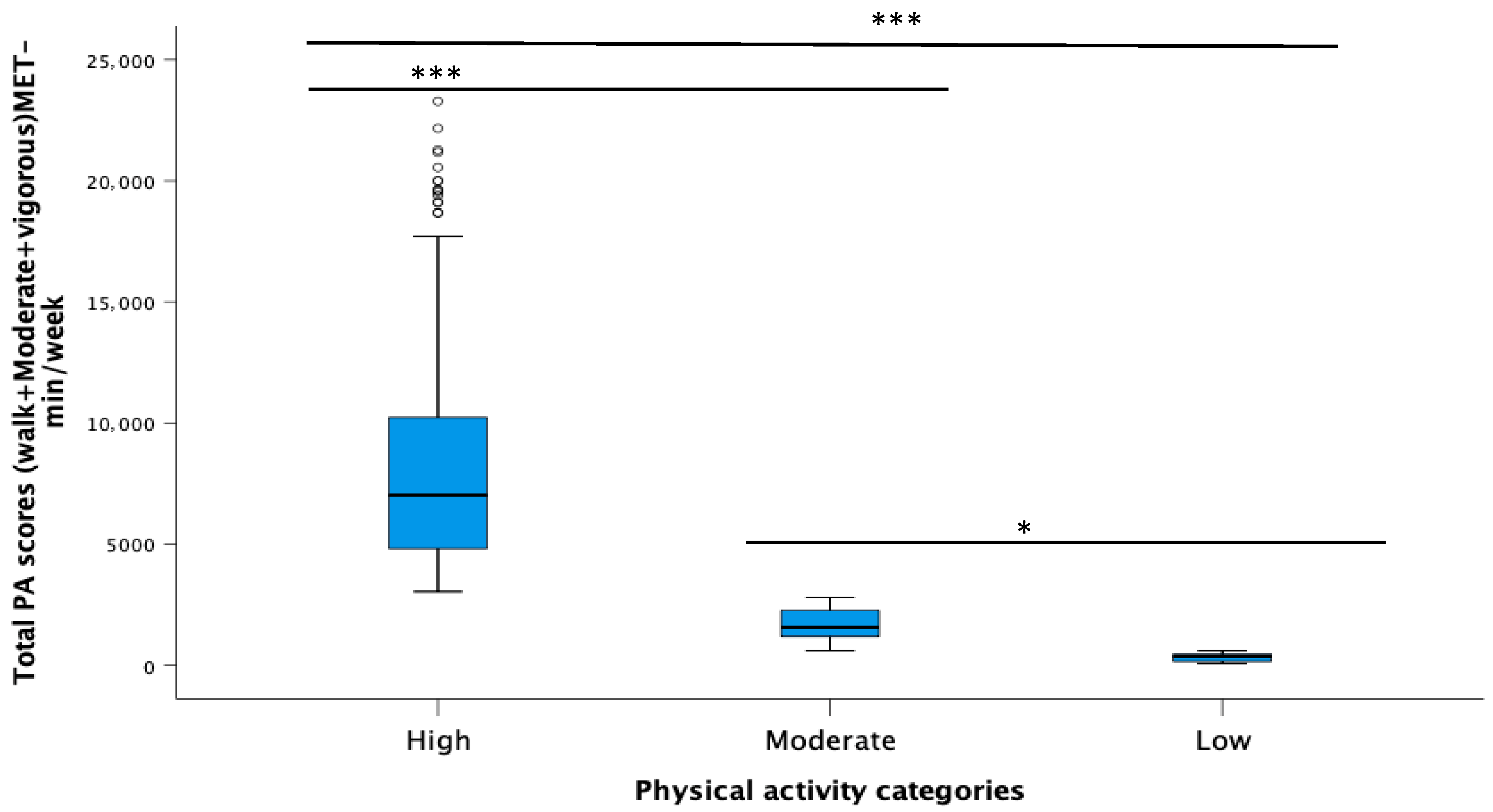

3.2. Total Weekly Physical Activity Among the Participants

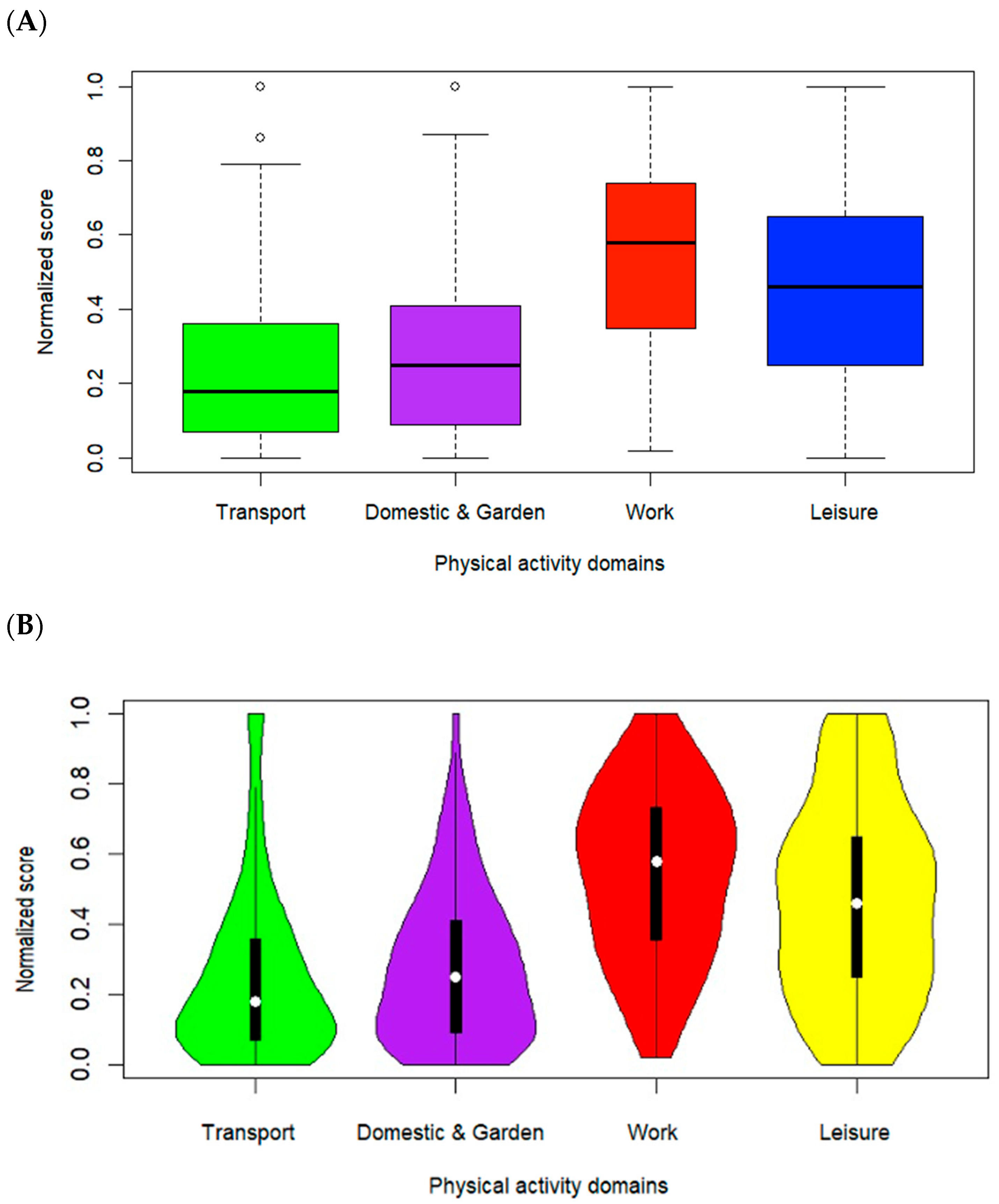

3.3. Gender Differences in Physical Activity Across IPAQ Domains

3.4. Total Physical Activity Stratified by Sociodemographic Characteristics

4. Discussion

5. Study Advantages and Limitations

5.1. Advantages

5.2. Study Limitations

6. Study Practical Implications

7. Conclusions

8. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bavel, J.J.; Baicker, K.; Boggio, P.S.; Capraro, V.; Cichocka, A.; Cikara, M.; Crockett, M.J.; Crum, A.J.; Douglas, K.M.; Druckman, J.N. Using Social and Behavioural Science to Support COVID-19 Pandemic Response. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constandt, B.; Thibaut, E.; Bosscher, V.; Scheerder, J.; Ricour, M.; Willem, A. Exercising in Times of Lockdown: An Analysis of the Impact of COVID-19 on Levels and Patterns of Exercise among Adults in Belgium. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzetta Ufficialee. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/Eli/Id/2020/03/11/20A01605/Sg (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Kaur, H.; Singh, T.; Arya, Y.K.; Mittal, S. Physical Fitness and Exercise during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Enquiry. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 590172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chtourou, H.; Trabelsi, K.; H’mida, C.; Boukhris, O.; Glenn, J.M.; Brach, M.; Bentlage, E.; Bott, N.; Shephard, R.J.; Ammar, A. Staying Physically Active during the Quarantine and Self-Isolation Period for Controlling and Mitigating the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Overview of the Literature. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coakley, K.E.; Lardier, D.T.; Holladay, K.R.; Amorim, F.T.; Zuhl, M.N. Physical Activity Behavior and Mental Health among University Students during COVID-19 Lockdown. Front. Sports Act. Living 2021, 3, 682175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ma, X.; Di, Q. Mental Health Problems during the COVID-19 Pandemics and the Mitigation Effects of Exercise: A Longitudinal Study of College Students in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Pavón, D.; Carbonell-Baeza, A.; Lavie, C.J. Physical Exercise as Therapy to Fight against the Mental and Physical Consequences of COVID-19 Quarantine: Special Focus in Older People. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020, 63, 386–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The Psychological Impact of Quarantine and How to Reduce It: Rapid Review of the Evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidetti, M.; Averna, A.; Castellini, G.; Dini, M.; Marino, D.; Bocci, T.; Ferrucci, R.; Priori, A. Physical Activity during COVID-19 Lockdown: Data from an Italian Survey. Healthcare 2021, 9, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkowski, S.; Buekers, J.; Rutkowska, A.; Cieślik, B.; Szczegielniak, J. Monitoring Physical Activity with a Wearable Sensor in Patients with COPD during In-Hospital Pulmonary Rehabilitation Program: A Pilot Study. Sensors 2021, 21, 2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemmler, W.; Stengel, S.; Kohl, M.; Bauer, J. Impact of Exercise Changes on Body Composition during the College Years—A Five Year Randomized Controlled Study. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racette, S.B.; Deusinger, S.S.; Strube, M.J.; Highstein, G.R.; Deusinger, R.H. Weight Changes, Exercise, and Dietary Patterns during Freshman and Sophomore Years of College. J. Am. Coll. Health 2005, 53, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, D.R.; Coster, D.C.; Paige, S.R. Physiological Health Parameters among College Students to Promote Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Prev. Med. Rep. 2017, 7, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bersia, M.; Charrier, L.; Zanaga, G.; Gaspar, T.; Moreno-Maldonado, C.; Grimaldi, P.; Koumantakis, E.; Dalmasso, P.; Comoretto, R.I. Well-being among university students in the post-COVID-19 era: A cross-country survey. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaccagni, L.; Toselli, S.; Gualdi-Russo, E. Recalling perceptions, emotions, behaviours, and changes in weight status among university students after the pandemic experience. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Z.; Lee, J.E. Promoting physical activity and reducing sedentary behavior to prevent chronic diseases during the COVID pandemic and beyond. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPherson, A.; Mackay, L.; Kunkel, J.; Duncan, S. Physical Activity, Cognition and Academic Performance: An Analysis of Mediating and Confounding Relationships in Primary School Children. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Liu, S.; Hu, S.; Feng, L.; Wang, H.; Gong, X.; Xuan, W.; Lu, T. The Effect of Inspiratory Muscle Training on Health-Related Fitness in College Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Booth, F.W.; Roberts, C.K.; Laye, M.J. Lack of Exercise Is a Major Cause of Chronic Diseases. Compr. Physiol. 2012, 2, 1143–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhateeb, S.A.; Alkhameesi, N.F.; Lamfon, G.N.; Khawandanh, S.Z.; Kurdi, L.K.; Faran, M.Y.; Khoja, A.A.; Bukhari, L.M.; Aljahdali, H.R.; Ashour, N.A. Pattern of Physical Exercise Practice among University Students in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (Before Beginning and During College): A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egli, T.; Bland, H.W.; Melton, B.F.; Czech, D.R. Influence of Age, Sex, and Race on College Students’ Exercise Motivation of Physical Activity. J. Am. Coll. Health 2011, 59, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.-P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R. World Health Organization 2020 Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latifi, A.; Flegr, J. Persistent Health and Cognitive Impairments up to Four Years Post-COVID-19 in Young Students: The Impact of Virus Variants and Vaccination Timing. Biomedicines 2024, 13, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maugeri, G.; Castrogiovanni, P.; Battaglia, G.; Pippi, R.; D’Agata, V.; Palma, A.; Di Rosa, M.; Musumeci, G. The Impact of Physical Activity on Psychological Health during Covid-19 Pandemic in Italy. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPAQ. Available online: https://sites.google.com/View/Ipaq/Home (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Boriani, G.; Guerra, F.; Ponti, R.; D’Onofrio, A.; Accogli, M.; Bertini, M.; Bisignani, G.; Forleo, G.B.; Landolina, M.; Lavalle, C. Five Waves of COVID-19 Pandemic in Italy: Results of a National Survey Evaluating the Impact on Activities Related to Arrhythmias, Pacing, and Electrophysiology Promoted by AIAC (Italian Association of Arrhythmology and Cardiac Pacing). Intern. Emerg. Med. 2023, 18, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, C.L.; Marshall, A.L.; Sjöström, M.; Bauman, A.E.; Booth, M.L.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Pratt, M.; Ekelund, U.; Yngve, A.; Sallis, J.F.; et al. International Physical Activity Questionnaire: 12-Country Reliability and Validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35, 1381–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallè, F.; Sabella, E.A.; Ferracuti, S.; Giglio, O.; Caggiano, G.; Protano, C.; Valeriani, F.; Parisi, E.A.; Valerio, G.; Liguori, G. Sedentary Behaviors and Physical Activity of Italian Undergraduate Students during Lockdown at the Time of CoViD-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghrir, M.H.; Borazjani, R.; Shiraly, R. COVID-19 and Iranian Medical Students; A Survey on Their Related-Knowledge, Preventive Behaviors and Risk Perception. Arch. Iran. Med. 2020, 23, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, G.; Laddu, D.R.; Phillips, S.A.; Lavie, C.J.; Arena, R. A Tale of Two Pandemics: How Will COVID-19 and Global Trends in Physical Inactivity and Sedentary Behavior Affect One Another? Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2021, 64, 108–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, F.; Song, Y.; Nassis, G.P.; Zhao, L.; Dong, Y.; Zhao, C.; Feng, Y.; Zhao, J. Physical Activity, Screen Time, and Emotional Well-Being during the 2019 Novel Coronavirus Outbreak in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bourdas, D.I.; Zacharakis, E.D. Impact of COVID-19 Lockdown on Physical Activity in a Sample of Greek Adults. Sports 2020, 8, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Sánchez, G.F.; Sánchez-Castillo, S.; López-Bueno, R.; Pardhan, S.; Zauder, R.; Skalska, M.; Jastrzębska, J.; Jastrzębski, Z.; Smith, L. Comparison of Physical Activity Levels in Spanish People with Diabetes with and without Cataracts. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 30, 1201–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giustino, V.; Parroco, A.M.; Gennaro, A.; Musumeci, G.; Palma, A.; Battaglia, G. Physical Activity Levels and Related Energy Expenditure during COVID-19 Quarantine among the Sicilian Active Population: A Cross-Sectional Online Survey Study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, L.A.; Gallo, T.F.; Young, S.L.; Moritz, K.M.; Akison, L.K. The Impact of Isolation Measures Due to COVID-19 on Energy Intake and Physical Activity Levels in Australian University Students. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate Daga, F.; Agostino, S.; Peretti, S.; Beratto, L. COVID-19 Nationwide Lockdown and Physical Activity Profiles among North-Western Italian Population Using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ). Sport Sci. Health 2021, 17, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunton, G.F.; Wang, S.D.; Do, B.; Courtney, J. Early Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Physical Activity Locations and Behaviors in Adults Living in the United States. Prev. Med. Rep. 2020, 20, 101241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand, R.; Timme, S.; Nosrat, S. When Pandemic Hits: Exercise Frequency and Subjective Well-Being during COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 570567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheval, B.; Sivaramakrishnan, H.; Maltagliati, S.; Fessler, L.; Forestier, C.; Sarrazin, P.; Orsholits, D.; Chalabaev, A.; Sander, D.; Ntoumanis, N.; et al. Relationships between changes in self-reported physical activity, sedentary behaviour and health during the COVID-19 pandemic in France and Switzerland. J. Sports Sci. 2020, 39, 699–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockwell, S.; Trott, M.; Tully, M.; Shin, J.; Barnett, Y.; Butler, L.; McDermott, D.; Schuch, F.; Smith, L. Changes in physical activity and sedentary behaviours from before to during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown: A systematic review. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2021, 7, e000960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awijen, H.; Ben Zaied, Y.; Nguyen, D.K. COVID-19 Vaccination, Fear and Anxiety: Evidence from Google Search Trends. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 297, 114820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallon, K. Exercise in the Time of COVID-19. Aust. J. Gen. Pr. 2020, 49, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, D.; del Pozo Cruz, B.; Green, M.A.; Bauman, A.E. Is the COVID-19 lockdown nudging people to be more active: A big data analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2021, 54, 1183–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-García, J.; Mañas, A.; González-Gross, M.; Espin, A.; Ara, I.; Ruiz, J.R.; Ortega, F.B.; Casajús, J.A.; Rodriguez-Larrad, A.; Irazusta, J. Physical Activity, Sleep, and Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A One-Year Longitudinal Study of Spanish University Students. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, D.; Walker, R.; Salway, R.; Emm-Collison, L.; Breheny, K.; Sansum, K.; Churchward, S.; Williams, J.G.; Vocht, F.; Jago, R. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Physical Activity Environment in English Primary Schools: A Multi-Perspective Qualitative Analysis. Public Health Res. 2024, 12, 59–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, F.; Bone, J.K.; Mitchell, J.J.; Steptoe, A.; Fancourt, D. Longitudinal Changes in Physical Activity during and after the First National Lockdown Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic in England. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 17723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yu, W.; Wu, X.; Wan, H.; Wang, Y.; Lu, G. Psychological Resilience and Positive Coping Styles among Chinese Undergraduate Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Psychol. 2020, 8, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ickes, M.J.; Dugan, A.; Bollinger, L.M. Changes in Physical Activity during the Initial Stages of the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Sports Sci. 2022, 40, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noonan, A.; Kennedy, S.; Norton, C.; Tierney, A.; Ng, K.; Woods, C. 152 the Role of Physical Activity and Strength Training on the Mental Health Outcomes of University Students across the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Repeated Cross-Sectional Study. Eur. J. Public Health 2024, 34, ckae114-191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tison, G.H.; Avram, R.; Kuhar, P.; Abreau, S.; Marcus, G.M.; Pletcher, M.J.; Olgin, J.E. Worldwide effect of COVID-19 on physical activity: A descriptive study. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e1327–e1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renzo, L.; Gualtieri, P.; Pivari, F.; Soldati, L.; Attinà, A.; Cinelli, G.; Leggeri, C.; Caparello, G.; Barrea, L.; Scerbo, F. Eating Habits and Lifestyle Changes during COVID-19 Lockdown: An Italian Survey. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniels, B.T.; Robinson, S.; Vargas, I.; Baum, J.I.; Howie, E.K. Changes in Physical Activity and Sleep Following the COVID-19 Pandemic on a University Campus: Perception versus Reality. Sports Med. Health Sci. 2024, 6, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albini, A.; Vecchia, C.; Magnoni, F.; Garrone, O.; Morelli, D.; Janssens, J.P.; Maskens, A.; Rennert, G.; Galimberti, V.; Corso, G. Physical Activity and Exercise Health Benefits: Cancer Prevention, Interception, and Survival. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2024, 34, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sañudo, B.; Fennell, C.; Sánchez-Oliver, A.J. Objectively-Assessed Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior, Smartphone Use, and Sleep Patterns Pre- and during-COVID-19 Quarantine in Young Adults from Spain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renati, R.; Bonfiglio, N.S.; Rollo, D. Italian University Students’ Resilience during the COVID-19 Lockdown-A Structural Equation Model about the Relationship between Resilience, Emotion Regulation and Well-Being. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2023, 13, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amornsriwatanakul, A.; Rahman, H.A.; Wattanapisit, A.; Nurmala, I.; Car, J.; Chia, M. University Students’ Overall and Domain-Specific Physical Activity during COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Study in Seven ASEAN Countries. Heliyon 2022, 8, e12466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagno, A.; Buonsenso, A.; Baralla, F.; Grazioli, E.; Martino, G.; Lecce, E.; Calcagno, G.; Fiorilli, G. Psychological Impact of the Quarantine-Induced Stress during the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Outbreak among Italian Athletes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consiglio, M.; Merola, S.; Pascucci, T.; Violani, C.; Couyoumdjian, A. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Italian University Students’ Mental Health: Changes across the Waves. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burtscher, M.; Burtscher, J.; Millet, G.P. (Indoor) isolation, stress, and physical inactivity: Vicious circles accelerated by COVID-19? Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2020, 30, 1544–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczak, B.B.; Kosendiak, A.A.; Kuźnik, Z.; Makles, S.; Hariasz, W. Gender Differences in Physical Activity Levels Among Overweight and Obese Medical Students During and After the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Single-Center Cross-Sectional Study. Obesities 2025, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matteucci, I.; Corsi, M.; Hurdiel, R.; Pezé, T.; Masson, P.; Porrovecchio, A. Health-Related Behavioral Changes during the COVID-19 Pandemic. A Comparison between Cohorts of French and Italian University Students. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2023, 3, e0002298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sembawa, S.N.; Jabr, A.S.; Banjar, A.A.; Alkuhayli, H.S.; Alotibi, M.S.; AlHawsawi, R.B.; Nasif, Y.A.; AlSaggaf, A.U. Physical Activity and Psychological Wellbeing among Healthcare Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Cureus 2024, 16, e55577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maté-Muñoz, J.L.; Hernández-Lougedo, J.; Ruiz-Tovar, J.; Olivares-Llorente, R.; García-Fernández, P.; Zapata, I. Physical Activity Levels, Eating Habits, and Well-Being Measures in Students of Healthcare Degrees in the Second Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertocchi, L.; Vecchio, R.; Sorbello, S.; Correale, L.; Gentile, L.; Buzzachera, C.; Gaeta, M.; Odone, A. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Physical Activity among University Students in Pavia, Northern Italy. Acta Biomed. 2021, 92, e2021443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Larrad, A.; Mañas, A.; Labayen, I.; González-Gross, M.; Espin, A.; Aznar, S.; Serrano-Sánchez, J.A.; Vera-Garcia, F.J.; González-Lamuño, D.; Ara, I. Impact of COVID-19 Confinement on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour in Spanish University Students: Role of Gender. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlandi, M.; Rosselli, M.; Pellegrino, A.; Boddi, M.; Stefani, L.; Toncelli, L.; Modesti, P.A. Gender Differences in the Impact on Physical Activity and Lifestyle in Italy during the Lockdown, Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2021, 31, 2173–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luciano, F.; Cenacchi, V.; Vegro, V.; Pavei, G. COVID-19 Lockdown: Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour and Sleep in Italian Medicine Students. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2021, 21, 1459–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roggio, F.; Trovato, B.; Ravalli, S.; Rosa, M.; Maugeri, G.; Bianco, A.; Palma, A.; Musumeci, G. One Year of COVID-19 Pandemic in Italy: Effect of Sedentary Behavior on Physical Activity Levels and Musculoskeletal Pain among University Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Blanco, C.; Rodríguez-Almagro, J.; Onieva-Zafra, M.D.; Parra-Fernández, M.L.; Prado-Laguna, M.D.C.; Hernández-Martínez, A. Physical Activity and Sedentary Lifestyle in University Students: Changes during Confinement Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celia, G.; Serio, G.; Trotta, E.; Tessitore, F.; Cozzolino, M. Psychological Wellbeing of Italian Students and Clinical Assessment Tools at University Counseling Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1388419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutz, M.; Gerke, M. Sport and Exercise in Times of Self-Quarantine: How Germans Changed Their Behaviour at the Beginning of the Covid-19 Pandemic. Leis. Stud. 2021, 56, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Characteristics | Frequency (N) | Percentage (%) | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age categories | 18–20 | 148 | 49.2 | 22.03 ± 4.9 |

| 21–30 | 136 | 45.2 | ||

| 31 and above | 17 | 5.6 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 132 | 43.9 | ||

| Female | 169 | 56.1 | ||

| Educational level | ||||

| Undergraduate | 272 | 90.4 | ||

| Graduate/Postgraduate | 17 | 5.6 | ||

| Other | 12 | 4 | ||

| Living status | ||||

| Living with families/others | 285 | 94.7 | ||

| Living alone | 16 | 5.3 | ||

| Monthly income | ||||

| <500 € | 193 | 64.1 | ||

| 500–1000 € | 42 | 14 | ||

| >1000 € | 66 | 21.9 | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.42 ± 3.77 | |||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 28 | 9.3 | ||

| Normal weight (18.5–24.9) | 222 | 73.8 | ||

| Preobese (25–29.9) | 46 | 15.3 | ||

| Obese (Class I, II and III) | 5 | 1.7 | ||

| Indicate the number in square meters (m2) in which you live in this period (COVID-19 pandemic): | ||||

| 10–100 | 145 | 48.2 | ||

| 101–200 | 125 | 41.5 | ||

| 201–400 | 31 | 10.3 | ||

| Indicate the type of house where you live in this period (COVID-19 pandemic): | ||||

| Urban residency | 234 | 77.7 | ||

| Suburban residency | 63 | 20.9 | ||

| Rural residency | 4 | 1.3 | ||

| Which sport/sport discipline do you practice? (Indicate only the main sport) | ||||

| Individual Sports | 128 | 42.5 | ||

| Collective sports | 67 | 22.3 | ||

| No main sports/other | 106 | 35.2 | ||

| Reported exercise obstacles during the COVID-19 pandemic | ||||

| Infrastructure closure and canceled sports events | 157 | 52.2 | ||

| Fear of COVID-19 and Health- Related Concerns | 30 | 10 | ||

| Personal and Motivational Factors | 114 | 37.9 | ||

| Employment status | ||||

| Employed (part-time) | 36 | 12 | ||

| Self-employed | 24 | 8 | ||

| Unemployed | 241 | 80.1 | ||

| Total PA (Walk + Moderate + Vigorous) | Frequency (N) | Percentage (%) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| High (>3000 MET-min/week) | 200 | 66.4 | |

| Moderate (600–3000 MET-min/week) | 80 | 26.6 | <0.001 |

| Low (<600 MET-min/week) | 21 | 7 | |

| Total number of respondents | 301 | 100 |

| IPAQ Domains | Gender | N | Mean ± SD | Levene’s Test (F, p Value) | t (df) | p Value | MD | 95% CI (Lower, Upper) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active Transport | Female | 151 | 0.28 ± 0.26 | 6.122 (0.014) | 2.30 (272) | 0.022 | 0.07 | (0.00962, 0.12283) |

| Male | 123 | 0.22 ± 0.21 | ||||||

| Domestic and Garden | Female | 111 | 0.32 ± 0.24 | 7.261 (0.008) | 2.76 (191) | 0.006 | 0.08 | (0.02376, 0.14233) |

| Male | 82 | 0.23 ± 0.18 | ||||||

| Work | Female | 55 | 0.52 ± 0.26 | 1.362 (0.246) | −1.12 (88) | 0.265 | −0.06 | (−0.16407, 0.04563) |

| Male | 35 | 0.58 ± 0.22 | ||||||

| Leisure | Female | 151 | 0.41 ± 0.28 | 0.624 (0.43) | −3.55 (273) | 0.000 | −0.12 | (−0.18283, −0.05247) |

| Male | 124 | 0.53 ± 0.26 | ||||||

| Group | N | Mean ± SD (MET-Min/Week) | p Value | Levene’s Test (F, p Value) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Physical activity (MET-min/Week) | Gender | Female | 169 | 5795.71 ± 5728.44 | 0.019 | |

| Male | 132 | 7490.77 ± 6697.66 | 0.092 (0.762) (t test) | |||

| Monthly Income | <500 € | 193 | 6281.18 ± 5484.19 | 0.042 | ||

| 500–1000 € | 42 | 8745.21 ± 8058.16 | ||||

| >1000 € | 66 | 5889.26 ± 6702.78 | 3.216 (ANOVA) | |||

| Age Group | 18–20 | 148 | 6912.48 ± 6289.51 | 0.577 | ||

| 21–30 | 136 | 6136.07 ± 6118.75 | ||||

| 31–45 | 17 | 6512.07 ± 6568.45 | 0.551 (ANOVA) | |||

| Surface Area (m2) | 10–100 | 145 | 6179.95 ± 5924.51 | 0.308 | ||

| 101–200 | 125 | 6576.77 ± 6366.58 | ||||

| 201–400 | 31 | 8066.68 ± 6905.58 | 1.181 (ANOVA) | |||

| Residency Type | Urban | 234 | 6201.00 ± 5682.03 | 0.001 | ||

| Suburban | 63 | 7085.64 ± 6545.47 | ||||

| Rural | 4 | 17,706.63 ± 17,118.56 | 7.336 (ANOVA) | |||

| Employment status | Employed (part-time) | 36 | 10,229.05 ± 9132.27 | 0.000 | ||

| Self-employed | 24 | 10,786.69 ± 6884.25 | ||||

| Unemployed | 241 | 5564.85 ± 5180.66 | 16.42 (ANOVA) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Benameur, T.; Saidi, N.; Panaro, M.A.; Porro, C. Physical Activity Patterns and Behavioral Resilience Among Foggia University Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Public Health Perspective. Healthcare 2026, 14, 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010087

Benameur T, Saidi N, Panaro MA, Porro C. Physical Activity Patterns and Behavioral Resilience Among Foggia University Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Public Health Perspective. Healthcare. 2026; 14(1):87. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010087

Chicago/Turabian StyleBenameur, Tarek, Neji Saidi, Maria Antonietta Panaro, and Chiara Porro. 2026. "Physical Activity Patterns and Behavioral Resilience Among Foggia University Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Public Health Perspective" Healthcare 14, no. 1: 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010087

APA StyleBenameur, T., Saidi, N., Panaro, M. A., & Porro, C. (2026). Physical Activity Patterns and Behavioral Resilience Among Foggia University Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Public Health Perspective. Healthcare, 14(1), 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010087