The Impact of Dance-Based Physical Activity on Sensorimotor and Psychological Function in Parkinson’s Disease: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Search Strategy and Evidence Selection

3. Results

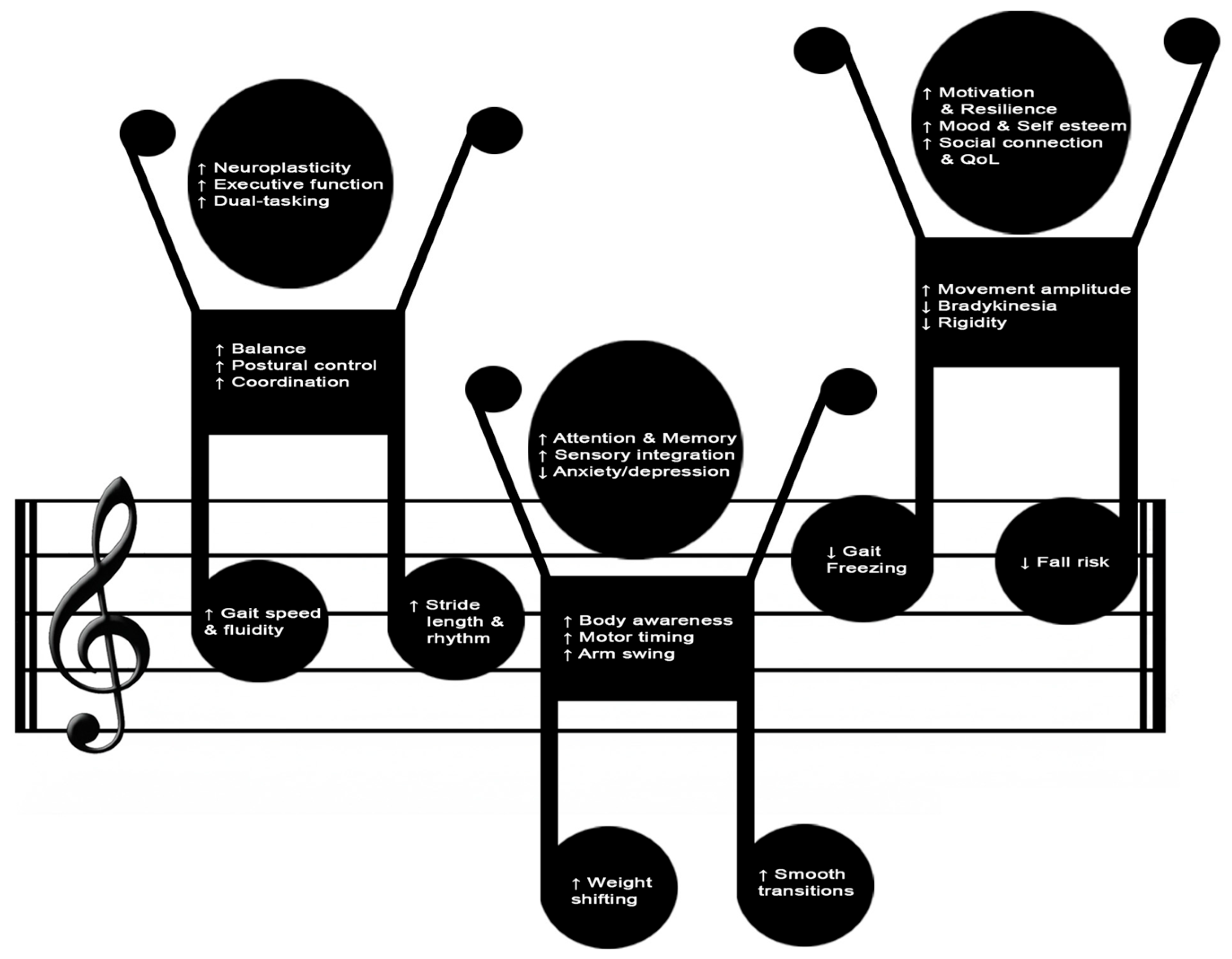

3.1. Psychophysical Benefits of Dance-Based Interventions in Parkinson’s Disease

3.2. Main Applied Dance Styles and Methodologies

3.2.1. Common Cross-Style Therapeutic Mechanisms

3.2.2. Argentine Tango

3.2.3. Ballroom Dance

3.2.4. Classical Ballet and Ballet Techniques

3.2.5. Contemporary Dance

3.2.6. Folk and Traditional Dance

3.2.7. Urban Dance

3.2.8. Comparative Synthesis of Evidence

4. Discussion and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

References

- Feigin, V.L.; Vos, T.; Nichols, E.; Owolabi, M.O.; Carroll, W.M.; Dichgans, M.; Deuschl, G.; Parmar, P.; Brainin, M.; Murray, C. The Global Burden of Neurological Disorders: Translating Evidence into Policy. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronek, P.; Haas, A.N.; Czarny, W.; Podstawski, R.; do Santos Delabary, M.; Clark, C.C.; Boraczyński, M.; Tarnas, M.; Wycichowska, P.; Pawlaczyk, M.; et al. The Mechanism of Physical Activity-Induced Amelioration of Parkinson’s Disease: A Narrative Review. Aging Dis. 2021, 12, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savica, R.; Grossardt, B.R.; Rocca, W.A.; Bower, J.H. Parkinson Disease with and without Dementia: A Prevalence Study and Future Projections. Mov. Disord. 2018, 33, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, F.; Farooqui, S.; Khan, I.A.; Hassan, B.; Afridi, Z.K. Effects of Exercise-Based Management on Motor Symptoms in Parkinson’s Disease—A Meta-Analysis. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2023, 33, 919–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorsey, E.R.; Sherer, T.; Okun, M.S.; Bloem, B.R. The Emerging Evidence of the Parkinson Pandemic. J. Parkinson’s Dis. 2018, 8, S3–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reich, S.G.; Savitt, J.M. Parkinson’s Disease. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 103, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, M.J.; Okun, M.S. Diagnosis and Treatment of Parkinson Disease: A Review. JAMA 2020, 323, 548–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, M.T. Parkinson’s Disease and Parkinsonism. Am. J. Med. 2019, 132, 802–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Agudo, R.D.; Lucena-Anton, D.; Luque-Moreno, C.; Heredia-Rizo, A.M.; Moral-Munoz, J.A. Additional Physical Interventions to Conventional Physical Therapy in Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-García, P.; Núñez de Arenas-Arroyo, S.; Cavero-Redondo, I.; Guzmán-Pavón, M.J.; Priego-Jiménez, S.; Álvarez-Bueno, C. Physical Exercise Interventions on Quality of Life in Parkinson Disease: A Network Meta-Analysis. J. Neurol. Phys. Ther. 2023, 47, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Balbuena, L.; Ungvari, G.S.; Zang, Y.-F.; Xiang, Y.-T. Quality of Life in Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Comparative Studies. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2021, 27, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Munster, E.P.J.; van der Aa, H.P.A.; Verstraten, P.; Heymans, M.W.; van Nispen, R.M.A. Improved Intention, Self-Efficacy and Social Influence in the Workspace May Help Low Vision Service Workers to Discuss Depression and Anxiety with Visually Impaired and Blind Adults. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carapellotti, A.M.; Meijerink, H.J.E.M.; Gravemaker-Scott, C.; Thielman, L.; Kool, R.; Lewin, N.; Abma, T.A. Escape, Expand, Embrace: The Transformational Lived Experience of Rediscovering the Self and the Other While Dancing with Parkinson’s or Multiple Sclerosis. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-being 2023, 18, 2143611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, A.A.; Chakravarthy, S.; Phillips, J.R.; Gupta, A.; Keri, S.; Polner, B.; Frank, M.J.; Jahanshahi, M. Motor Symptoms in Parkinson’s Disease: A Unified Framework. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 68, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- di Biase, L.; Summa, S.; Tosi, J.; Taffoni, F.; Marano, M.; Cascio Rizzo, A.; Vecchio, F.; Formica, D.; Di Lazzaro, V.; Di Pino, G.; et al. Quantitative Analysis of Bradykinesia and Rigidity in Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirakawa, Y.; Sakurai, H.; Takeda, K.; Koyama, S.; Iwai, M.; Motoya, I.; Kanada, Y.; Kawamura, N.; Kawamura, M.; Tanabe, S. Relationship Between Each of the Four Major Motor Symptoms and At-Home Physical Activity in Individuals with Parkinson’s Disease: A Cross-Sectional Study. Neurol. Int. 2025, 17, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieruccini-Faria, F.; Jones, J.A.; Almeida, Q.J. Insight into Dopamine-Dependent Planning Deficits in Parkinson’s Disease: A Sharing of Cognitive & Sensory Resources. Neuroscience 2016, 318, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamilselvam, Y.K.; Jog, M.; Patel, R.V. Robot-Assisted Investigation of Sensorimotor Control in Parkinson’s Disease. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falletti, M.; Asci, F.; Zampogna, A.; Patera, M.; Suppa, A. Cogwheel Rigidity in Parkinson’s Disease: Clinical, Biomechanical and Neurophysiological Features. Neurobiol. Dis. 2025, 212, 106980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viseux, F.J.F.; Delval, A.; Defebvre, L.; Simoneau, M. Postural Instability in Parkinson’s Disease: Review and Bottom-up Rehabilitative Approaches. Neurophysiol. Clin. 2020, 50, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abusrair, A.H.; Elsekaily, W.; Bohlega, S. Tremor in Parkinson’s Disease: From Pathophysiology to Advanced Therapies. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov. 2022, 12, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonstra, T.A.; van der Kooij, H.; Munneke, M.; Bloem, B.R. Gait Disorders and Balance Disturbances in Parkinson’s Disease: Clinical Update and Pathophysiology. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2008, 21, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirelman, A.; Bonato, P.; Camicioli, R.; Ellis, T.D.; Giladi, N.; Hamilton, J.L.; Hass, C.J.; Hausdorff, J.M.; Pelosin, E.; Almeida, Q.J. Gait Impairments in Parkinson’s Disease. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloem, B.R.; Hausdorff, J.M.; Visser, J.E.; Giladi, N. Falls and Freezing of Gait in Parkinson’s Disease: A Review of Two Interconnected, Episodic Phenomena. Mov. Disord. 2004, 19, 871–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite Silva, A.B.R.; Gonçalves de Oliveira, R.W.; Diógenes, G.P.; de Castro Aguiar, M.F.; Sallem, C.C.; Lima, M.P.P.; de Albuquerque Filho, L.B.; Peixoto de Medeiros, S.D.; Penido de Mendonça, L.L.; de Santiago Filho, P.C.; et al. Premotor, Nonmotor and Motor Symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease: A New Clinical State of the Art. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 84, 101834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opara, J.A.; Brola, W.; Leonardi, M.; Błaszczyk, B. Quality of Life in Parkinson’s Disease. J. Med. Life 2012, 5, 375–381. [Google Scholar]

- Marinus, J.; Ramaker, C.; van Hilten, J.J.; Stiggelbout, A.M. Health Related Quality of Life in Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review of Disease Specific Instruments. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2002, 72, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, H.-W.; Hong, S.-W.; Youn, Y.C. Clinical Aspects of the Differential Diagnosis of Parkinson’s Disease and Parkinsonism. J. Clin. Neurol. 2022, 18, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intzandt, B.; Beck, E.N.; Silveira, C.R.A. The Effects of Exercise on Cognition and Gait in Parkinson’s Disease: A Scoping Review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2018, 95, 136–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeWitt, P.A. Levodopa Therapy for Parkinson’s Disease: Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics. Mov. Disord. 2015, 30, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, X.; Li, F.; Li, Q.; Jin, Y. Efficacy of Non-Pharmacological Interventions for Depression in Individuals with Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 1050715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnish, M.S.; Reynolds, S.E.; Nelson-Horne, R.V. Active Group-Based Performing Arts Interventions in Parkinson’s Disease: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e089920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kola, S.; Subramanian, I. Updates in Parkinson’s Disease Integrative Therapies: An Evidence-Based Review. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2023, 23, 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šumec, R.; Filip, P.; Sheardová, K.; Bareš, M. Psychological Benefits of Nonpharmacological Methods Aimed for Improving Balance in Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review. Behav. Neurol. 2015, 2015, 620674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloem, B.R.; de Vries, N.M.; Ebersbach, G. Nonpharmacological Treatments for Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. 2015, 30, 1504–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinazzi, M.; Abbruzzese, G.; Antonini, A.; Ceravolo, R.; Fabbrini, G.; Lessi, P.; Barone, P.; REASON Study Group. Reasons Driving Treatment Modification in Parkinson’s Disease: Results from the Cross-Sectional Phase of the REASON Study. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2013, 19, 1130–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, L.D.; Frank, L.L.; Foster-Schubert, K.; Green, P.S.; Wilkinson, C.W.; McTiernan, A.; Plymate, S.R.; Fishel, M.A.; Watson, G.S.; Cholerton, B.A.; et al. Effects of Aerobic Exercise on Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Controlled Trial. Arch. Neurol. 2010, 67, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-García, P.; Cavero-Redondo, I.; Núñez de Arenas-Arroyo, S.; Guzmán-Pavón, M.J.; Priego-Jiménez, S.; Álvarez-Bueno, C. Effects of Physical Exercise Interventions on Balance, Postural Stability and General Mobility in Parkinson’s Disease: A Network Meta-Analysis. J. Rehabil. Med. 2024, 56, jrm10329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberts, J.L.; Rosenfeldt, A.B. The Universal Prescription for Parkinson’s Disease: Exercise. J. Parkinson’s Dis. 2020, 10, S21–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguh, O.; Eisenstein, A.; Kwasny, M.; Simuni, T. Back to the Basics: Regular Exercise Matters in Parkinson’s Disease: Results from the National Parkinson Foundation QII Registry Study. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2014, 20, 1221–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalsing, K.S.; Abbas, M.M.; Tan, L.C.S. Role of Physical Activity in Parkinson’s Disease. Ann. Indian Acad. Neurol. 2018, 21, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, M.K.; Wong-Yu, I.S.; Shen, X.; Chung, C.L. Long-Term Effects of Exercise and Physical Therapy in People with Parkinson Disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2017, 13, 689–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabino-Carvalho, J.L.; Fisher, J.P.; Vianna, L.C. Autonomic Function in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: From Rest to Exercise. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 626640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaagman, D.G.M.; van Wegen, E.E.H.; Cignetti, N.; Rothermel, E.; Vanbellingen, T.; Hirsch, M.A. Effects and Mechanisms of Exercise on Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) Levels and Clinical Outcomes in People with Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahalakshmi, B.; Maurya, N.; Lee, S.-D.; Bharath Kumar, V. Possible Neuroprotective Mechanisms of Physical Exercise in Neurodegeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia Ruiz, P.J.; Luquin Piudo, R.; Martinez Castrillo, J.C. On Disease Modifying and Neuroprotective Treatments for Parkinson’s Disease: Physical Exercise. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 938686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshari, M.; Yang, A.; Bega, D. Motivators and Barriers to Exercise in Parkinson’s Disease. J. Parkinson’s Dis. 2017, 7, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schootemeijer, S.; van der Kolk, N.M.; Ellis, T.; Mirelman, A.; Nieuwboer, A.; Nieuwhof, F.; Schwarzschild, M.A.; de Vries, N.M.; Bloem, B.R. Barriers and Motivators to Engage in Exercise for Persons with Parkinson’s Disease. J. Parkinson’s Dis. 2020, 10, 1293–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Li, D.; Yue, L.; Xie, J. The Effects of Exercise Dose on Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Neurol. 2023, 270, 5327–5343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Lai, B.; Mehta, T.; Thirumalai, M.; Padalabalanarayanan, S.; Rimmer, J.H.; Motl, R.W. Exercise Training Guidelines for Multiple Sclerosis, Stroke, and Parkinson Disease: Rapid Review and Synthesis. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2019, 98, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carapellotti, A.M.; Stevenson, R.; Doumas, M. The Efficacy of Dance for Improving Motor Impairments, Non-Motor Symptoms, and Quality of Life in Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, B.; Rigby, A.; Gnerre, M.; Biassoni, F. The Effects of a Dance and Music-Based Intervention on Parkinson’s Patients’ Well-Being: An Interview Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, L.; Youmans-Jones, J. Dance Is a Healing Art. Curr. Treat. Options Allergy 2023, 10, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earhart, G.M. Dance as Therapy for Individuals with Parkinson Disease. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2009, 45, 231–238. [Google Scholar]

- Haputhanthirige, N.K.H.; Sullivan, K.; Moyle, G.; Brauer, S.; Jeffrey, E.R.; Kerr, G. Effects of Dance on Gait and Dual-Task Gait in Parkinson’s Disease. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0280635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeely, M.E.; Duncan, R.P.; Earhart, G.M. Impacts of Dance on Non-Motor Symptoms, Participation, and Quality of Life in Parkinson Disease and Healthy Older Adults. Maturitas 2015, 82, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong Yan, A.; Cobley, S.; Chan, C.; Pappas, E.; Nicholson, L.L.; Ward, R.E.; Murdoch, R.E.; Gu, Y.; Trevor, B.L.; Vassallo, A.J.; et al. The Effectiveness of Dance Interventions on Physical Health Outcomes Compared to Other Forms of Physical Activity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 933–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raje, P.; Ning, S.; Branson, C.; Saint-Hilaire, M.; de Leon, M.P.; DePold Hohler, A. Self-Reported Exercise Trends in Parkinson’s Disease Patients. Complement. Ther. Med. 2019, 42, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmanouilidis, S.; Hackney, M.E.; Slade, S.C.; Heng, H.; Jazayeri, D.; Morris, M.E. Dance Is an Accessible Physical Activity for People with Parkinson’s Disease. Parkinson’s Dis. 2021, 2021, 7516504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnish, M.S.; Barran, S.M. A Systematic Review of Active Group-Based Dance, Singing, Music Therapy and Theatrical Interventions for Quality of Life, Functional Communication, Speech, Motor Function and Cognitive Status in People with Parkinson’s Disease. BMC Neurol. 2020, 20, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, J.D.S.; Alcantara, W.A.; Brito, J.S.; Barbosa, L.C.S.; Machado, I.P.R.; Furtado, V.K.T.; Santos-Lobato, B.L.D.; Pinto, D.S.; Krejcová, L.V.; Bahia, C.P. Physical Activity Based on Dance Movements as Complementary Therapy for Parkinson’s Disease: Effects on Movement, Executive Functions, Depressive Symptoms, and Quality of Life. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0281204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, S.R.; Lee, S.W.H.; Merom, D.; Megat Kamaruddin, P.S.N.; Chong, M.S.; Ong, T.; Lai, N.M. Evidence of Disease Severity, Cognitive and Physical Outcomes of Dance Interventions for Persons with Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bearss, K.A.; Barnstaple, R.E.; Bar, R.J.; DeSouza, J.F.X. Impact of Weekly Community-Based Dance Training Over 8 Months on Depression and Blood Oxygen Level-Dependent Signals in the Subcallosal Cingulate Gyrus for People with Parkinson Disease: Observational Study. JMIRx Med. 2024, 5, e44426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bearss, K.A.; DeSouza, J.F.X. Parkinson’s Disease Motor Symptom Progression Slowed with Multisensory Dance Learning over 3-Years: A Preliminary Longitudinal Investigation. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carapellotti, A.M.; Rodger, M.; Doumas, M. Evaluating the Effects of Dance on Motor Outcomes, Non-Motor Outcomes, and Quality of Life in People Living with Parkinson’s: A Feasibility Study. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2022, 8, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bognar, S.; DeFaria, A.M.; O’Dwyer, C.; Pankiw, E.; Simic Bogler, J.; Teixeira, S.; Nyhof-Young, J.; Evans, C. More than Just Dancing: Experiences of People with Parkinson’s Disease in a Therapeutic Dance Program. Disabil. Rehabil. 2017, 39, 1073–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bek, J.; Arakaki, A.I.; Derbyshire-Fox, F.; Ganapathy, G.; Sullivan, M.; Poliakoff, E. More Than Movement: Exploring Motor Simulation, Creativity, and Function in Co-Developed Dance for Parkinson’s. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 731264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bek, J.; Arakaki, A.I.; Lawrence, A.; Sullivan, M.; Ganapathy, G.; Poliakoff, E. Dance and Parkinson’s: A Review and Exploration of the Role of Cognitive Representations of Action. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 109, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, K.; Alshaikh, J.T.; Pantelyat, A. Music Therapy and Music-Based Interventions for Movement Disorders. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2019, 19, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeely, M.E.; Mai, M.M.; Duncan, R.P.; Earhart, G.M. Differential Effects of Tango Versus Dance for PD in Parkinson Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2015, 7, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moratelli, J.A.; Alexandre, K.H.; Boing, L.; Swarowsky, A.; Corrêa, C.L.; de Guimarães, A.C.A. Dance Rhythms Improve Motor Symptoms in Individuals with Parkinson’s Disease: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Dance Med. Sci. 2022, 26, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackney, M.E.; Earhart, G.M. Effects of Dance on Gait and Balance in Parkinson’s Disease: A Comparison of Partnered and Nonpartnered Dance Movement. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2010, 24, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos Delabary, M.; Komeroski, I.G.; Monteiro, E.P.; Costa, R.R.; Haas, A.N. Effects of Dance Practice on Functional Mobility, Motor Symptoms and Quality of Life in People with Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2018, 30, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, P.R.; Moratelli, J.A.; Fausto, D.Y.; Alexandre, K.H.; Garcia Meliani, A.A.; Lima, A.G.; Guimarães, A.C.d.A. The Importance of Dance for the Cognitive Function of People with Parkinson’s: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2024, 40, 2091–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, S.M.; Alshafie, S.; Hasabo, E.A.; Saleh, M.; Elnaiem, W.; Qasem, A.; Alzu’bi, Y.O.; Khaled, A.; Zaazouee, M.S.; Ragab, K.M.; et al. Efficacy of Dance for Parkinson’s Disease: A Pooled Analysis of 372 Patients. J. Neurol. 2022, 269, 1195–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiberger, L.; Maurer, C.; Amtage, F.; Mendez-Balbuena, I.; Schulte-Mönting, J.; Hepp-Reymond, M.-C.; Kristeva, R. Impact of a Weekly Dance Class on the Functional Mobility and on the Quality of Life of Individuals with Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2011, 3, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGill, A.; Houston, S.; Lee, R.Y.W. Dance for Parkinson’s: A New Framework for Research on Its Physical, Mental, Emotional, and Social Benefits. Complement. Ther. Med. 2014, 22, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carretti, G.; Mirandola, D.; Sgambati, E.; Manetti, M.; Marini, M. Survey on Psychological Well-Being and Quality of Life in Visually Impaired Individuals: Dancesport vs. Other Sound Input-Based Sports. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackney, M.E.; McKee, K. Community-Based Adapted Tango Dancing for Individuals with Parkinson’s Disease and Older Adults. J. Vis. Exp. 2014, e52066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios Romenets, S.; Anang, J.; Fereshtehnejad, S.-M.; Pelletier, A.; Postuma, R. Tango for Treatment of Motor and Non-Motor Manifestations in Parkinson’s Disease: A Randomized Control Study. Complement. Ther. Med. 2015, 23, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, F.; Platano, D.; Berti, L.; Donati, D.; Tedeschi, R. Dancing Towards Stability: The Therapeutic Potential of Argentine Tango for Balance and Mobility in Parkinson’s Disease. Diseases 2025, 13, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blandy, L.M.; Beevers, W.A.; Fitzmaurice, K.; Morris, M.E. Therapeutic Argentine Tango Dancing for People with Mild Parkinson’s Disease: A Feasibility Study. Front. Neurol. 2015, 6, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, W.M.; Hackney, M.E. Adapted Tango for Adults with Parkinson’s Disease: A Qualitative Study. Adapt. Phys. Activ. Q. 2017, 34, 256–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lötzke, D.; Ostermann, T.; Büssing, A. Argentine Tango in Parkinson Disease--a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Neurol. 2015, 15, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashburn, A.; Roberts, L.; Pickering, R.; Roberts, H.C.; Wiles, R.; Kunkel, D.; Hulbert, S.; Robison, J.; Fitton, C. A Design to Investigate the Feasibility and Effects of Partnered Ballroom Dancing on People with Parkinson Disease: Randomized Controlled Trial Protocol. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2014, 3, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunkel, D.; Fitton, C.; Roberts, L.; Pickering, R.M.; Roberts, H.C.; Wiles, R.; Hulbert, S.; Robison, J.; Ashburn, A. A Randomized Controlled Feasibility Trial Exploring Partnered Ballroom Dancing for People with Parkinson’s Disease. Clin. Rehabil. 2017, 31, 1340–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackney, M.E.; Earhart, G.M. Effects of Dance on Movement Control in Parkinson’s Disease: A Comparison of Argentine Tango and American Ballroom. J. Rehabil. Med. 2009, 41, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, S.; McGill, A. A Mixed-Methods Study into Ballet for People Living with Parkinson’s. Arts Health 2013, 5, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haussler, A.M.; Tueth, L.E.; Earhart, G.M. Feasibility of a Barre Exercise Intervention for Individuals with Mild to Moderate Parkinson Disease. J. Dance Med. Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podlewska, A.M.; Batzu, L.; Soukup, T.; Sevdalis, N.; Bakolis, I.; Derbyshire-Fox, F.; Hartley, A.; Healey, A.; Woods, A.; Crane, N.; et al. The PD-Ballet Study: Study Protocol for a Randomised Controlled Single-Blind Hybrid Type 2 Clinical Trial Evaluating the Effects of Ballet Dancing on Motor and Non-Motor Symptoms in Parkinson’s Disease. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2024, 24, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde-Guijarro, E.; Alguacil-Diego, I.M.; Vela-Desojo, L.; Cano-de-la-Cuerda, R. Effects of Contemporary Dance and Physiotherapy Intervention on Balance and Postural Control in Parkinson’s Disease. Disabil. Rehabil. 2022, 44, 2632–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar, A.; Czamanski-Cohen, J.; Federman, J.D. I Feel Like I Am Flying and Full of Life: Contemporary Dance for Parkinson’s Patients. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 623721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, E.C.; Earhart, G.M.; Leventhal, D.; Quinn, L.; Mazzoni, P. A Walking Dance to Improve Gait Speed for People with Parkinson Disease: A Pilot Study. Neurodegener. Dis. Manag. 2020, 10, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solla, P.; Cugusi, L.; Bertoli, M.; Cereatti, A.; Della Croce, U.; Pani, D.; Fadda, L.; Cannas, A.; Marrosu, F.; Defazio, G.; et al. Sardinian Folk Dance for Individuals with Parkinson’s Disease: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Trial. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2019, 25, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, J.; Bhriain, O.N.; Morris, M.E.; Volpe, D.; Clifford, A.M. Irish Set Dancing Classes for People with Parkinson’s Disease: The Needs of Participants and Dance Teachers. Complement. Ther. Med. 2016, 27, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanahan, J.; Morris, M.E.; Bhriain, O.N.; Volpe, D.; Lynch, T.; Clifford, A.M. Dancing for Parkinson Disease: A Randomized Trial of Irish Set Dancing Compared with Usual Care. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2017, 98, 1744–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volpe, D.; Signorini, M.; Marchetto, A.; Lynch, T.; Morris, M.E. A Comparison of Irish Set Dancing and Exercises for People with Parkinson’s Disease: A Phase II Feasibility Study. BMC Geriatr. 2013, 13, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sistarelli, S.; Annett, L.E.; Lovatt, P.J. Effects of Popping for Parkinson’s Dance Class on the Mood of People with Parkinson’s Disease. Int. J. Ther. Rehabil. 2023, 30, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, K.; Hewitt, J. Dance as an Intervention for People with Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2014, 47, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, P.A.; Slade, S.C.; McClelland, J.; Morris, M.E. Dance Is More than Therapy: Qualitative Analysis on Therapeutic Dancing Classes for Parkinson’s. Complement. Ther. Med. 2017, 34, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, R.P.; Earhart, G.M. Randomized Controlled Trial of Community-Based Dancing to Modify Disease Progression in Parkinson Disease. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2012, 26, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, P.; Discenzo, F.M.; Kim, J.H.; Lemke, Z.; Meggitt, J.; Ridgel, A.L. Analysis of Movement Entropy during Community Dance Programs for People with Parkinson’s Disease and Older Adults: A Cohort Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, J.R.; Bek, J.; Ghanai, K.; Bearss, K.A.; Barnstaple, R.E.; Bar, R.J.; DeSouza, J.F.X. Neural Effects of Multisensory Dance Training in Parkinson’s Disease: Evidence from a Longitudinal Neuroimaging Single Case Study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2024, 16, 1398871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaut, M.H.; Kenyon, G.P.; Schauer, M.L.; McIntosh, G.C. The Connection between Rhythmicity and Brain Function. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Mag. 1999, 18, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volpe, D.; Baldassarre, M.G.; Bakdounes, L.; Campo, M.C.; Ferrazzoli, D.; Ortelli, P. “Dance Well”-A Multisensory Artistic Dance Intervention for People with Parkinson’s Disease: A Pilot Study. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, J.L.; McKay, J.L.; Sawers, A.; Hackney, M.E.; Ting, L.H. Increased Neuromuscular Consistency in Gait and Balance after Partnered, Dance-Based Rehabilitation in Parkinson’s Disease. J. Neurophysiol. 2017, 118, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.P.S.; Marinho, V.; Gupta, D.; Magalhães, F.; Ayres, C.; Teixeira, S. Music Therapy and Dance as Gait Rehabilitation in Patients with Parkinson Disease: A Review of Evidence. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2019, 32, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, H.; Takabatake, S.; Miyaguchi, H.; Nakanishi, H.; Naitou, Y. Effects of Dance on Motor Functions, Cognitive Functions, and Mental Symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease: A Quasi-Randomized Pilot Trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 2015, 23, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, M.I.; Barnes, D.E.; Ross, J.M.; Lanni, K.E.; Sigvardt, K.A.; Disbrow, E.A. A Pilot Study to Evaluate Multi-Dimensional Effects of Dance for People with Parkinson’s Disease. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2016, 51, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashoori, A.; Eagleman, D.M.; Jankovic, J. Effects of Auditory Rhythm and Music on Gait Disturbances in Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Neurol. 2015, 6, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulbert, S.; Ashburn, A.; Roberts, L.; Verheyden, G. Dance for Parkinson’s-The Effects on Whole Body Co-Ordination during Turning Around. Complement. Ther. Med. 2017, 32, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, H.M.; Al-Turkistani, Z.I.; Alayat, M.S.; Abd El-Kafy, E.M.; El Fiky, A.A.R. Effect of Dancing on Freezing of Gait in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. NeuroRehabilitation 2023, 53, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krotinger, A.; Loui, P. Rhythm and Groove as Cognitive Mechanisms of Dance Intervention in Parkinson’s Disease. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalyani, H.H.N.; Sullivan, K.; Moyle, G.; Brauer, S.; Jeffrey, E.R.; Roeder, L.; Berndt, S.; Kerr, G. Effects of Dance on Gait, Cognition, and Dual-Tasking in Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Parkinson’s Dis. 2019, 9, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camicioli, R.; Morris, M.E.; Pieruccini-Faria, F.; Montero-Odasso, M.; Son, S.; Buzaglo, D.; Hausdorff, J.M.; Nieuwboer, A. Prevention of Falls in Parkinson’s Disease: Guidelines and Gaps. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 2023, 10, 1459–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreasson, I.; Björkdahl, A.; Fristedt, S.; Bergman, P.; Filipowicz, K.; Johansson, I.-K.; Santos Tavares Silva, I. Dance for Parkinson, Multifaceted Experiences of Persons Living with Parkinson’s Disease. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2024, 31, 2411206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGill, A.; Houston, S.; Lee, R.Y.W. Effects of a Ballet-Based Dance Intervention on Gait Variability and Balance Confidence of People with Parkinson’s. Arts Health 2019, 11, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, S.C.; Mergheim, K.; Raeke, J.; Machado, C.B.; Riegner, E.; Nolden, J.; Diermayr, G.; von Moreau, D.; Hillecke, T.K. The Embodied Self in Parkinson’s Disease: Feasibility of a Single Tango Intervention for Assessing Changes in Psychological Health Outcomes and Aesthetic Experience. Front. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, J.; Morris, M.E.; Bhriain, O.N.; Saunders, J.; Clifford, A.M. Dance for People with Parkinson Disease: What Is the Evidence Telling Us? Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2015, 96, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezzarobba, S.; Bonassi, G.; Avanzino, L.; Pelosin, E. Action Observation and Motor Imagery as a Treatment in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. J. Parkinson’s Dis. 2024, 14, S53–S64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Hu, J.; Wei, L.; Jia, Y.; Jin, Y. Effects of Dance Therapy on Cognitive and Mood Symptoms in People with Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2019, 36, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, C.; Annett, L.E.; Davenport, S.; Hall, A.A.; Lovatt, P. Mood Changes Following Social Dance Sessions in People with Parkinson’s Disease. J. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magrath, J.; Kenny, S.J.; Ingstrup, M.S.; Morrison, L.; Paglione, V.; McDonough, M.H.; Din, C. “We’re All Here to Be Dancers Together”: Perspectives on Facilitating Dance Classes for Individuals with Parkinson’s. Adapt. Phys. Activ. Q. 2025, 42, 343–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupacher, J.; Matthews, T.E.; Pando-Naude, V.; Foster Vander Elst, O.; Vuust, P. The Sweet Spot between Predictability and Surprise: Musical Groove in Brain, Body, and Social Interactions. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 906190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundström, M.; Jola, C. “I’m Never Going to Be in Phantom of the Opera”: Relational and Emotional Wellbeing of Parkinson’s Carers and Their Partners in and Beyond Dancing. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 636135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westheimer, O.; McRae, C.; Henchcliffe, C.; Fesharaki, A.; Glazman, S.; Ene, H.; Bodis-Wollner, I. Dance for PD: A Preliminary Investigation of Effects on Motor Function and Quality of Life among Persons with Parkinson’s Disease (PD). J. Neural Transm. 2015, 122, 1263–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, S.J.; Dale, M.J.; Bail, K. “Out and Proud…. in All Your Shaking Glory” the Wellbeing Impact of a Dance Program with Public Dance Performance for People with Parkinson’s Disease: A Qualitative Study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2023, 45, 3272–3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, W.-H.; Quan, Y.; Thompson, W.F. The Effect of Dance on Mental Health and Quality of Life of People with Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Three-Level Meta-Analysis. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2024, 120, 105326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, R.; Robichaud, S. Evaluating Dancing with Parkinson’s: Reflections from the Perspective of a Community Organization. Eval. Program. Plann. 2020, 80, 101449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaseinasrabadi, R.; DeSouza, J. Dancing through the Darkness: A Systematic Review of Dance as a Multidimensional Therapy for Parkinson’s Disease. Neurodegener. Dis. Manag. 2025. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, E.R.; Golden, L.; Duncan, R.P.; Earhart, G.M. Community-Based Argentine Tango Dance Program Is Associated with Increased Activity Participation among Individuals with Parkinson’s Disease. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2013, 94, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, L.; Norris, M.L.; Columna, L. “Keep Moving”: Experiences of People with Parkinson’s and Their Care Partners in a Dance Class. Adapt. Phys. Activ. Q. 2021, 38, 307–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senter, M.; Ni Bhriain, O.; Clifford, A.M. “You Need to Know That You Are Not Alone”: The Sustainability of Community-Based Dance Programs for People Living with Parkinson’s Disease. Disabil. Rehabil. 2025, 47, 5871–5884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitch, W.T.; Barnstaple, R. Dance as Mindful Movement: A Perspective from Motor Learning and Predictive Coding. BMC Neurosci. 2024, 25, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharpure, V.; Parab, S.; Ryain, A.; Ghosh, A. Therapeutic Potential of Recreation on Non-Motor Symptoms in Parkinson’s Disease: A Literature Review. Adv. Mind Body Med. 2024, 38, 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel, D.; Robison, J.; Fitton, C.; Hulbert, S.; Roberts, L.; Wiles, R.; Pickering, R.; Roberts, H.; Ashburn, A. It Takes Two: The Influence of Dance Partners on the Perceived Enjoyment and Benefits during Participation in Partnered Ballroom Dance Classes for People with Parkinson’s. Disabil. Rehabil. 2018, 40, 1933–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyrling, T.; Ljunggren, M.; Karlsson, S. The Impact of Dance Activities on the Health of Persons with Parkinson’s Disease in Sweden. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-being 2021, 16, 1992842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nombela, C.; Hughes, L.E.; Owen, A.M.; Grahn, J.A. Into the Groove: Can Rhythm Influence Parkinson’s Disease? Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2013, 37, 2564–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackney, M.E.; Kantorovich, S.; Levin, R.; Earhart, G.M. Effects of Tango on Functional Mobility in Parkinson’s Disease: A Preliminary Study. J. Neurol. Phys. Ther. 2007, 31, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Dreu, M.J.; Kwakkel, G.; van Wegen, E.E.H. Partnered Dancing to Improve Mobility for People with Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Docu Axelerad, A.; Stroe, A.Z.; Muja, L.F.; Docu Axelerad, S.; Chita, D.S.; Frecus, C.E.; Mihai, C.M. Benefits of Tango Therapy in Alleviating the Motor and Non-Motor Symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease Patients—A Narrative Review. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, S.; Crock, N.D.; Billings, B.J.; Wu, R.; Sterling, S.; Koul, S.; Taber, W.F.; Pique, K.; Golan, R.; Maitland, G. Argentine Tango Reduces Fall Risk in Parkinson’s Patients. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 291–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawson, K.S.; McNeely, M.E.; Duncan, R.P.; Pickett, K.A.; Perlmutter, J.S.; Earhart, G.M. Exercise and Parkinson Disease: Comparing Tango, Treadmill, and Stretching. J. Neurol. Phys. Ther. 2019, 43, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Natale, E.R.; Paulus, K.S.; Aiello, E.; Sanna, B.; Manca, A.; Sotgiu, G.; Leali, P.T.; Deriu, F. Dance Therapy Improves Motor and Cognitive Functions in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. NeuroRehabilitation 2017, 40, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabini, G.; Meli, C.; Prodomi, G.; Speranza, C.; Anzini, F.; Funghi, G.; Pierotti, E.; Saviola, F.; Fumagalli, G.G.; Di Giacopo, R.; et al. Tango and Physiotherapy Interventions in Parkinson’s Disease: A Pilot Study on Efficacy Outcomes on Motor and Cognitive Skills. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poier, D.; Rodrigues Recchia, D.; Ostermann, T.; Büssing, A. A Randomized Controlled Trial to Investigate the Impact of Tango Argentino versus Tai Chi on Quality of Life in Patients with Parkinson Disease: A Short Report. Complement. Med. Res. 2019, 26, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinovich, D.B.; Garretto, N.S.; Arakaki, T.; DeSouza, J.F. A High Dose Tango Intervention for People with Parkinson’s Disease (PwPD). Adv. Integr. Med. 2021, 8, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyani, H.H.; Sullivan, K.A.; Moyle, G.M.; Brauer, S.G.; Jeffrey, E.R.; Kerr, G.K. Dance Improves Symptoms, Functional Mobility and Fine Manual Dexterity in People with Parkinson Disease: A Quasi-Experimental Controlled Efficacy Study. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2020, 56, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.-C.; Xiong, H.-Y.; Zheng, J.-J.; Wang, X.-Q. Dance Movement Therapy for Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Systematic Review. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 975711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeely, M.E.; Duncan, R.P.; Earhart, G.M. A Comparison of Dance Interventions in People with Parkinson Disease and Older Adults. Maturitas 2015, 81, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haussler, A.M.; Earhart, G.M. The Effectiveness of Classical Ballet as a Therapeutic Intervention: A Narrative Review. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2023, 29, 102–109. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, A.; Hart, A.; Bozzorg, A.; Pothineni, S.; Wolf, S.L.; Schuh, K.; Caughlan, M.; Parker, J.; Blackwell, A.; Tharp Cianflona, M.; et al. Comparison of Externally and Internally Guided Dance Movement to Address Mobility, Cognition, and Psychosocial Function in People with Parkinson’s Disease and Freezing of Gait: A Case Series. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2024, 16, 1372894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jochum, E.; Egholm, D.; Oliveira, A.S.; Jacobsen, S.L. The Effects of Folk-Dance in Schools on Physical and Mental Health for at-Risk Adolescents: A Pilot Intervention Study. Front. Sports Act. Living 2024, 6, 1434661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delabary, M.D.S.; Loch Sbeghen, I.; Teixeira da Silva, E.C.; Guzzo Júnior, C.C.E.; Nogueira Haas, A. Brazilian Dance Self-Perceived Impacts on Quality of Life of People with Parkinson’s. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1356553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elpidoforou, M.; Bakalidou, D.; Drakopoulou, M.; Kavga, A.; Chrysovitsanou, C.; Stefanis, L. Effects of a Structured Dance Program in Parkinson’s Disease. A Greek Pilot Study. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2022, 46, 101528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, A.; Dugani, P.; Mahale, R.; Nandakumar; Haskar Dhanyamraju, K.; Pradeep, R.; Javali, M.; Acharya, P.; Srinivasa, R. Garba Dance Is Effective in Parkinson’s Disease Patients: A Pilot Study. Parkinson’s Dis. 2024, 2024, 5580653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillmann, A.C.; Andrade, A.; Swarowsky, A.; Guimarães, A.C.D.A. Brazilian Samba Protocol for Individuals with Parkinson’s Disease: A Clinical Non-Randomized Study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2017, 6, e129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bocchi Martins, J.B.; Amaral da Rocha, A.R.; Fausto, D.Y.; da Silva, E.; da Silva, G.; Pinheiro, G.P.; de Azevedo Guimarães, A.C. Comparing Urban Dance and Functional Fitness for Postmenopausal Women: A Randomized Clinical Trial Protocol. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2025, 310, 113936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, Y.; Noh, G. Tango Therapy for Parkinson’s Disease: Effects of Rush Elemental Tango Therapy. Clin. Case Rep. 2020, 8, 970–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Quiroga, S.A.; Rey, R.D.; Arakaki, T.; Garretto, N.S. Dramatic Improvement of Parkinsonism While Dancing Tango. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 2014, 1, 388–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, G.; Hugenschmidt, C.E.; Soriano, C.T. Verbal Auditory Cueing of Improvisational Dance: A Proposed Method for Training Agency in Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Neurol. 2016, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carapellotti, A.M.; Rodger, M.; Doumas, M. Evaluating the Short-Term Effects of Dance on Motor and Non-Motor Outcomes in People Living with Parkinson’s: A Crossover Study. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0328293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hackney, M.E.; Earhart, G.M. Health-Related Quality of Life and Alternative Forms of Exercise in Parkinson Disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2009, 15, 644–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Wang, X.; Lu, S.; Ying, X. A Study of Bidirectional Control of Parkinson’s Beta Oscillations by Basal Ganglia. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2025, 195, 116267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westheimer, O. Why Dance for Parkinson’s Disease. Top. Geriatr. Rehabil. 2008, 24, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moratelli, J.; Alexandre, K.H.; Boing, L.; Swarowsky, A.; Corrêa, C.L.; Guimarães, A.C.d.A. Binary Dance Rhythm or Quaternary Dance Rhythm Which Has the Greatest Effect on Non-Motor Symptoms of Individuals with Parkinson’s Disease? Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2021, 43, 101348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunet, J.; Saunders, S.; Gifford, W.; Thomas, R.; Hamilton, R. An Exploratory Qualitative Study of the Meaning and Value of a Running/Walking Program for Women after a Diagnosis of Breast Cancer. Disabil. Rehabil. 2018, 40, 1041–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannery, M. Self-Determination Theory: Intrinsic Motivation and Behavioral Change. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2017, 44, 155–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahon, J.; Chazot, P. Dance and Parkinson’s: Biological Perspective and Rationale. Lifestyle Med. 2020, 1, e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saluja, A.; Goyal, V.; Dhamija, R.K. Multi-Modal Rehabilitation Therapy in Parkinson’s Disease and Related Disorders. Ann. Indian Acad. Neurol. 2023, 26, S15–S25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, R.; Maranesi, E.; Benadduci, M.; Cortellessa, G.; Umbrico, A.; Fracasso, F.; Melone, G.; Margaritini, A.; La Forgia, A.; Di Bitonto, P.; et al. Exploring Dance as a Therapeutic Approach for Parkinson Disease Through the Social Robotics for Active and Healthy Ageing (SI-Robotics): Results from a Technical Feasibility Study. JMIR Aging 2025, 8, e62930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, R.; Benadduci, M.; Bonfigli, A.R.; Riccardi, G.R.; Melone, G.; La Forgia, A.; Macchiarulo, N.; Rossetti, L.; Marzorati, M.; Rizzo, G.; et al. Dancing With Parkinson’s Disease: The SI-ROBOTICS Study Protocol. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 780098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goka, K.A.; Agormedah, E.K.; Achina, S.; Segbenya, M. How Dimensions of Participatory Decision Making Influence Employee Performance in the Health Sector: A Developing Economy Perspective. J. Chin. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2024, 15, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez-Llort, L.; Castillo-Mariqueo, L. PasoDoble, a Proposed Dance/Music for People with Parkinson’s Disease and Their Caregivers. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 567891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croft, S.; Fraser, S. A Scoping Review of Barriers and Facilitators Affecting the Lives of People with Disabilities During COVID-19. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 2021, 2, 784450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carretti, G.; Tognaccini, A.; Baldini, G.; Manetti, M.; Marini, M. Kinesiological Insights into Exercise Prescription within Oncological Prehabilitation: Current Knowledge and Future Perspectives. Front. Sports Act. Living 2025, 7, 1715484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonardi, F. The Definition of Health: Towards New Perspectives. Int. J. Health Serv. 2018, 48, 735–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dance Style | Primary Investigated Outcomes | Main Reported Effects | Evidence-Based Interpretation | Main References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentine Tango | Motor function: gait, stride length, balance, turning, postural stability, and PD-specific motor scales. Cognitive outcomes: spatial cognition, executive function, and attention. Psychosocial outcomes: mood, quality of life, and fatigue. Feasibility, safety, and adherence. | Consistent improvements in gait dynamics/parameters, rhythmic coordination, balance, postural stability, and functional mobility. Reduced fall risk. Cognitive-motor benefits (visuospatial cognition, motor planning, and executive function). Enhanced mood and quality of life. High feasibility, adherence, and enjoyment. | Moderate-strong evidence for improving motor and non-motor domains. Benefits due to combination of rhythmic cueing, partner interaction, cognitive engagement, and dynamic balance challenges. Highly promising and feasible movement-based therapy for PD. | [79,80,81,82,83,87,114,118,131,139,141,142,143,145,146,147,159,160] |

| Ballroom Dance | Motor function: balance, gait speed, stride length, mobility, and PD-specific motor scales. Cognitive outcomes: executive function and visuospatial skills. Psychosocial outcomes: quality of life, mood, and emotional regulation. | Consistent improvements in balance with moderate-strong gains in gait and functional mobility. Enhanced quality of life and positive effects on mood and emotional wellbeing. Cognitive benefits (executive function and visuospatial cognition). | Reliable benefits in balance, gait, and quality of life for individuals with PD. Motor and psychosocial benefits due to variegated rhythm/styles engagement, coordinative/cognitive demands, and motor–cognitive integration. Feasible and clinically valuable movement-based therapy for PD. | [85,86,87,100,136,148,149] |

| Classical Ballet and Ballet Techniques | Motor function: gait/gait variability, balance, postural control, mobility, freezing of gait, and strength. Cognitive outcomes: attention, executive function, and cue-responsiveness. Psychosocial outcomes: psychological and emotional wellbeing. Feasibility and acceptability. | Motor benefits, reduced gait variability, improved balance confidence, postural alignment, and weight-shift control. Improved mobility in individuals experiencing freezing of gait. Psychosocial benefits, enhanced confidence, wellbeing, and social connection. High adherence, enjoyment, and feasibility. | External cues and rhythmic guidance help bypass impaired internal motor generation, especially freezing of gait. Emphasis on postural alignment and controlled weight transfer improve gait consistency and perceived stability. Feasible and clinically valuable movement-based therapy for PD. | [88,90,117,151,152] |

| Contemporary Dance | Motor function: gait, postural control, balance, and functional mobility. Cognitive outcomes: attention, executive function, and cue-responsiveness. Psychosocial outcomes: psychological and emotional wellbeing, quality of life. Feasibility and acceptability. | Improved gait, balance, postural control, and mobility. Enhanced self-perception, mood, psychosocial wellbeing, and quality of life. High feasibility and engagement. | External cues and rhythmic guidance help bypass impaired internal motor generation. Psychosocial benefits due to creative, expressive, and participant-driven approaches. Self-perception, motivation, and motor–cognitive improvements due to unconventional movements. Feasible and clinically valuable movement-based therapy for PD. | [65,67,91,92,152,161,162] |

| Folk and Traditional Dance | Motor function: gait, postural control, balance, and PD-specific motor scales. Cognitive outcomes: attention, executive function, and dual-task performance. Psychosocial outcomes: psychological and emotional wellbeing, quality of life, and social engagement. Feasibility and adherence. | Improved gait, balance, postural control, and functional mobility. Enhanced mood, social engagement, psychological wellbeing, and quality of life. High feasibility, engagement, and adherence. | External cues and rhythmic guidance help bypass impaired internal motor generation. Group-based/formation patterns and repetitive/predictable step sequences improve motor–cognitive integration and movement confidence. Psychosocial benefits due to multiple styles/rhythm, social engagement, and cultural relevance/adaptability. Feasible and clinically valuable movement-based therapy for PD. | [61,94,95,96,105,154,155,156,157] |

| Urban Dance (i.e., Popping) | Mood. | Short-term improved mood, decreased depression and confusion. | Rhythmic emphasis (syncopated percussive beats) stimulates dopaminergic pathways and motor timing. Mood benefits due to proprioceptive awareness stimulation, creative self-expression, and interactive/playful context. | [98] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Carretti, G.; Guidi, L.; Manetti, M.; Marini, M. The Impact of Dance-Based Physical Activity on Sensorimotor and Psychological Function in Parkinson’s Disease: A Narrative Review. Healthcare 2026, 14, 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010105

Carretti G, Guidi L, Manetti M, Marini M. The Impact of Dance-Based Physical Activity on Sensorimotor and Psychological Function in Parkinson’s Disease: A Narrative Review. Healthcare. 2026; 14(1):105. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010105

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarretti, Giuditta, Lorenzo Guidi, Mirko Manetti, and Mirca Marini. 2026. "The Impact of Dance-Based Physical Activity on Sensorimotor and Psychological Function in Parkinson’s Disease: A Narrative Review" Healthcare 14, no. 1: 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010105

APA StyleCarretti, G., Guidi, L., Manetti, M., & Marini, M. (2026). The Impact of Dance-Based Physical Activity on Sensorimotor and Psychological Function in Parkinson’s Disease: A Narrative Review. Healthcare, 14(1), 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010105