Piloting an In Situ Training Program in Video Consultations in a Gynaecological Outpatient Clinic at a University Hospital: A Qualitative Study of the Healthcare Professionals’ Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

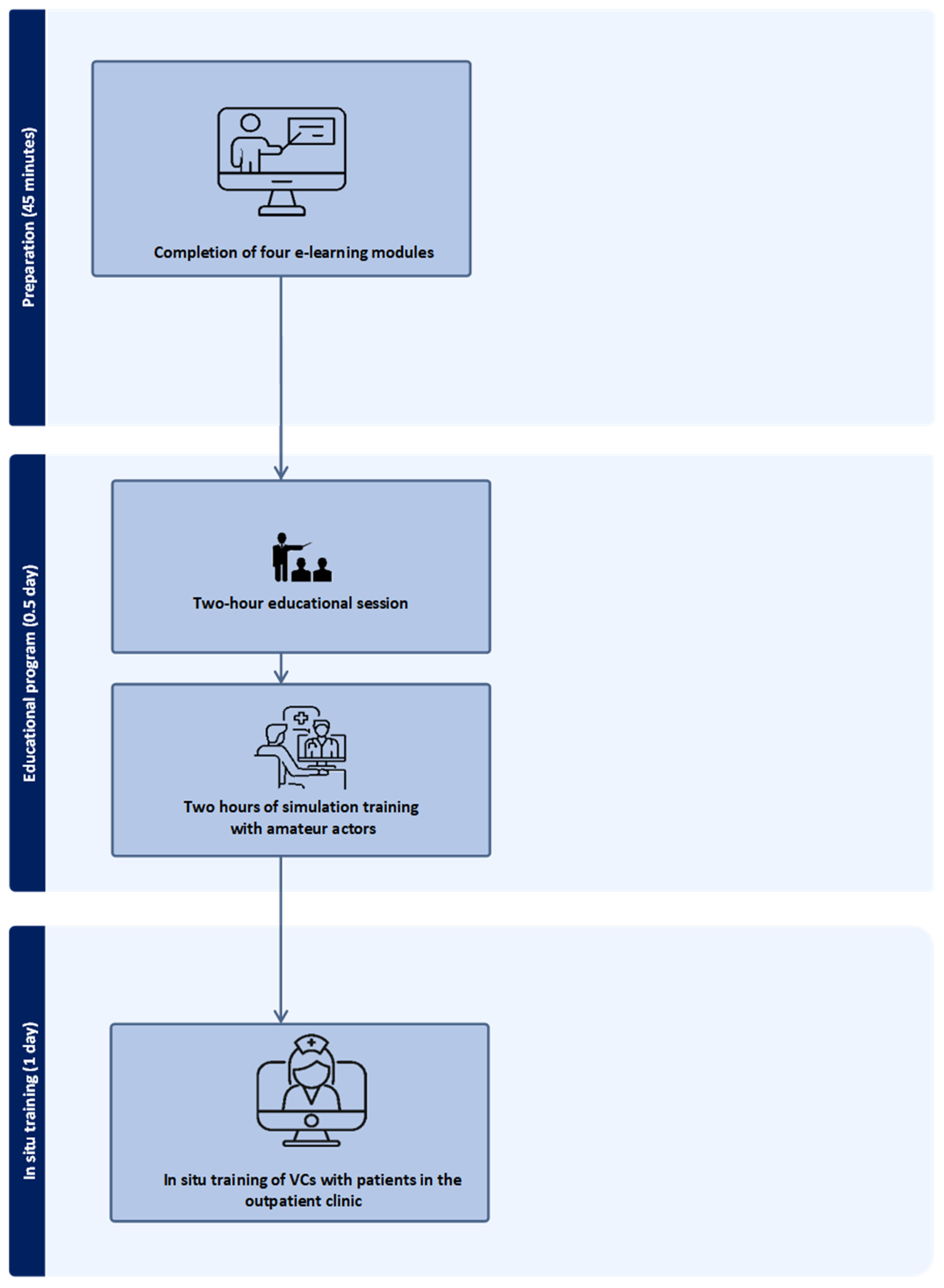

2.1. Setting and Intervention

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethics

3. Results

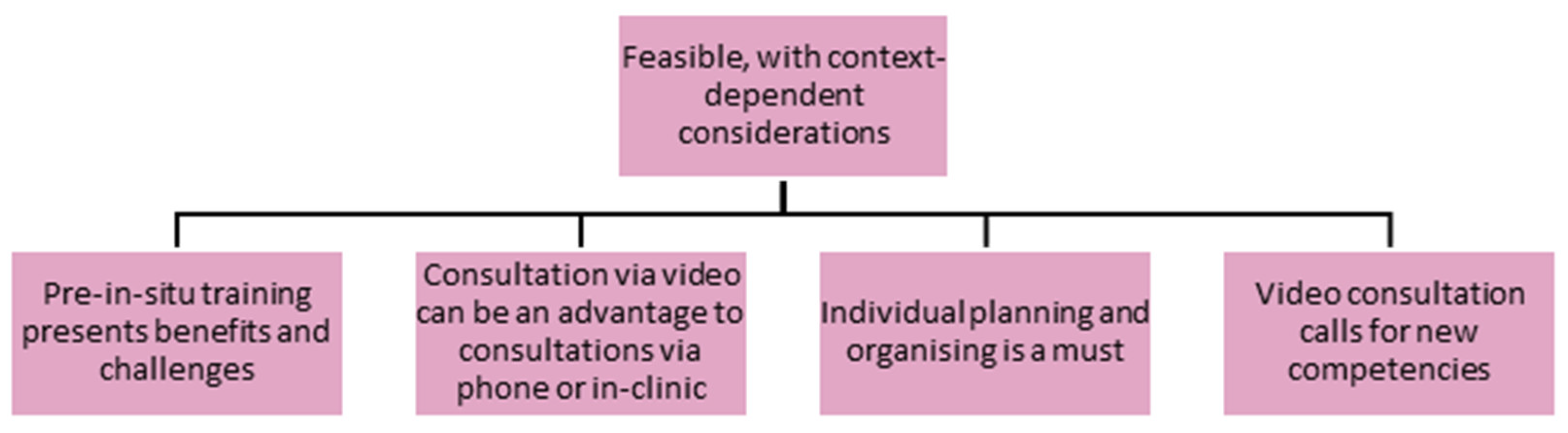

3.1. Overall Theme: Feasible, with Context-Dependent Considerations

It is essential to let the clinicians at the outpatient clinics assess when and where they would like to implement video consultation. They are close to the patients and have a feel for who among the patients could benefit. We listen to the patients and will not just implement it everywhere.(Participant 1, doctor)

Video consultation must be seen from the patient’s perspective and needs. We [HCPs] must be careful not to introduce it too early and thus influence the patients to accept participation.(Participant 2, doctor)

3.2. Theme 1: Pre-In Situ Training Presents Benefits and Challenges

The interaction between lecturing and practical exercises was significant(Participant 5, nurse)

It is essential to have the training program before one starts on the technical and communicative part of video consultation, not only using bedside training by peers.(Participant 4, nurse)

Feedback was a gift. During the two days, there could have been even more focus on feedback on the in situ training with the patients. The feedback is where one develops oneself and learns. The combination of technical, practical training and communication, including exercises, overstepped boundaries, and one learned a lot.(Participant 3, doctor)

We need the other colleagues in the team to be in (to take the course as well). We are only a few [HCPs] in this training so far. The risk is that we forget how we did it before adequately implementing it.(Participant 5, nurse)

3.3. Theme 2: Consultation via Video Can Be Advantageous over Consultations via Phone or In-Clinic

Video [consultation] is a handy tool for face-to-face communication. I can see the benefits that they (patients) are at home—in their safe environment, and at the same time, do not have the inconvenience of coming in [to the hospital].(Participant 2, doctor)

An advantage is that when there is an infection risk, the vulnerable patients may have a good conversation in their homes without exposure.(Participant 4, doctor)

[At video consultations], the family can be present as well.(Participant 1, doctor)

They [patients] have not met me before, so [compared to a phone consultation], it gives a much more intimate conversation when you can see each other.(Participant 1, doctor)

[It gives] more to see a face and make eye contact (rather than only phone consultation). One (HCPs) can watch the atmosphere and see how they are. Further, the patient can get a feel for me as a person, and it brings “safety” into the conversation.(Participant 3, doctor)

A closing conversation may be done more quickly on video as the patient is not in the room.(Participant 2, doctor)

I experience that it [the full consultation] takes more time with video. Thus, attention must be paid to the planning of our programs.(Participant 8, nurse)

The patient can be [if called on the telephone] [out] playing golf or driving [or] be out for a walk or in Foetex [a supermarket].(Participant 1, doctor)

My experience was that the patients were more engaged and ready for the (video) conversation than for face-to-face meetings in the clinic. They appeared more severe and alert than in face-to-face meetings.(Participant 7, Nurse)

3.4. Theme 3: Individual Planning and Organisation Are a Must

Video consultation must be seen from the patient’s perspective and needs.(Participant 2, doctor)

If the outcome is patient satisfaction, we will do it.(Participant 4, nurse)

Video consultation will be perfect for rehabilitating conversations where physical examination is unnecessary. Conversations about where assessment is needed and where and when plans must be agreed upon may also be doable [in video consultation].(Participant 1, doctor)

It’s problematic that it [a video consultation] is so inflexible compared to a phone conversation—on an ordinary day, when I receive a cancellation, I can phone—I cannot do a video [consultation] as it must be scheduled for a specific time.(Participant 4, doctor)

3.5. Theme 4: Video Consultation Calls for New Competencies

The clinicians must evaluate where they would like to implement video (consultation). They sit with the patients, listen, and have an eye for which patients could benefit.(Participant 1, doctor)

There are differences in how fast one (HCP) picks it up (competencies in video consultation). Skills in technique and backup are necessary.(Participant 4, doctor)

Anyway, I am not equipped for this video thing [consultation]; it would make my everyday life at work difficult, and I would be sad if I were ordered [by management] to do it.(Participant 4, doctor)

I feel much more positive now. Testing it [video consultation] and evaluating it afterwards is beneficial. However, the slight advantage I experience from video consultation gets lost compared to the lack of flexibility and difficulty in handling the tool.(Participant 2, doctor)

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Warmoth, K.; Lynch, J.; Darlington, N.; Bunn, F.; Goodman, C. Using video consultation technology between care homes and health and social care professionals: A scoping review and interview study during COVID-19 pandemic. Age Ageing 2022, 51, afab279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanderås, M.R.; Abildsnes, E.; Thygesen, E.; Martinez, S.G. Video consultation in general practice: A scoping review on use, experiences, and clinical decisions. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weigel, G.; Ramaswamy, A.; Sobel, L.; Salganicoff, A.; Cubanski, J.; Freed, M. Opportunities and Barriers for Telemedicine in the U.S. During the COVID-19 Emergency and Beyond. Available online: https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/opportunities-and-barriers-for-telemedicine-in-the-u-s-during-the-covid-19-emergency-and-beyond/ (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- Shaver, J. The State of Telehealth Before and After the COVID-19 Pandemic. Prim. Care Respir. J. J. Gen. Pract. Airw. Group 2022, 49, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, C.K.; Gillis, K. The Use of Telemedicine by Physicians: Still the Exception Rather Than the Rule. Health Aff. 2018, 37, 1923–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Region Syddanmark. Region Syddanmark Sætter Skub i Udviklingen af Virtuelle Konsultationer. [The Region of Southern Denmark Acclerates the Development of Virual Consultations]. Available online: https://regionsyddanmark.dk/om-region-syddanmark/presse-og-nyheder/nyhedsarkiv/2022/december-2022/region-syddanmark-saetter-skub-i-udviklingen-af-virtuelle-konsultationer (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Snoswell, C.L.; Taylor, M.L.; A Comans, T.; Smith, A.C.; Gray, L.C.; Caffery, L.J. Determining if Telehealth Can Reduce Health System Costs: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 19, e17298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schutz, S.; Walthall, H.; Snowball, J.; Vagner, R.; Fernandez, N.; Bartram, E.; Merriman, C. Patient and clinician experiences of remote consultation during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: A service evaluation. Digit. Health 2022, 8, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, L.F.; Moller, A.M.; Hansen, J.P.; Nielsen, C.T.; Gildberg, F.A. Patients’ and providers’ experiences with video consultations used in the treatment of older patients with unipolar depression: A systematic review. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2019, 27, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinman, R.S.; Kimp, A.J.; Campbell, P.K.; Russell, T.; Foster, N.E.; Kasza, J.; Harris, A.; Bennell, K.L. Technology versus tradition: A non-inferiority trial comparing video to face-to-face consultations with a physiotherapist for people with knee osteoarthritis. Protocol for the PEAK randomised controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2020, 21, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Region Syddanmark. Digitaliseringsstrategi 2022–2024. [Stragegy for Digitalising 2022–2024]. Available online: https://regionsyddanmark.dk/media/3srnkq4r/digitaliseringsstrategi-2022-2024_pdfversion.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Region Syddanmark. Mit Sygehus—En App til Dig, der er Patient i Region Syddanmark. [My Hospital—An app for you, who are a patient in the Region of Southern Denmark]. Available online: https://regionsyddanmark.dk/patienter-og-parorende/hjaelp-til-patienter-og-parorende/mit-sygehus (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Levine, D.M.; Ouchi, K.; Blanchfield, B.; Saenz, A.; Burke, K.; Paz, M.; Diamond, K.; Pu, C.T.; Schnipper, J.L. Hospital-Level Care at Home for Acutely Ill Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 172, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funderskov, K.F.; Raunkiær, M.; Danbjørg, D.B.; Zwisler, A.-D.; Munk, L.; Jess, M.; Dieperink, K.B. Experiences With Video Consultations in Specialized Palliative Home-Care: Qualitative Study of Patient and Relative Perspectives. J. Med Internet Res. 2019, 21, e10208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, Y.; Vseteckova, J.; Mastellos, N.; Greenfield, G.; Randhawa, G. Diagnosis and Decision-Making in Telemedicine. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2019, 12, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartori, D.J.; Hayes, R.W.; Horlick, M.; Adams, J.G.; Zabar, S.R. The TeleHealth OSCE: Preparing Trainees to Use Telemedicine as a Tool for Transitions of Care. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2020, 12, 764–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ammentorp, J.; Basset, B.; Dinesen, J.; Lau, M. Den Gode Patient Samtale. [Patient Communication], 1st ed.; Munksgaard: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz, S.; Draper, J.; Silverman, J. Teaching and Learning Communication Skills in Medicine, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: London, UK, 2017; p. 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, S.; Tangaard, L. Qualitative Methods; Hans Reitzels Forlag: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2020; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Toward good practice in thematic analysis: Avoiding common problems and be(com)ing a knowing researcher. Int. J. Transgender Health 2023, 24, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Gareth, T. Thematic Analysis; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Råd, S. De sygeplejeetiske retningslinjer. [Nurse Ethical Guidelines]. Dansk Sygeplejeråds Kongres 2014, 26, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Mattsson, T.O.; Lindhart, C.L.; Schöley, J.; Friis-Hansen, L.; Herrstedt, J. Patient self-testing of white blood cell count and differentiation: A study of feasibility and measurement performance in a population of Danish cancer patients. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2020, 29, e13189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Albornoz, S.C.; Sia, K.-L.; Harris, A. The effectiveness of teleconsultations in primary care: Systematic review. Fam. Pract. 2022, 39, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Møller, O.M.; Vange, S.S.; Borsch, A.S.; Mandal Møller, O.; Vange, S.S.; Dam, T.N.; Jervelund, S.S. Medical specialists’ use and opinion of video consultation in Denmark: A survey study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Handbook of Self-Determination Research; University Rochester Press: Rochester, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lungeforeningen. De Digitale Løsninger er Fremtidens Stetoskop. Digital Solutionsis the Future Stetoscope. Available online: https://www.lunge.dk/behandling/viden-praktiserende-laege-de-digitale-loesninger-er-fremtidens-stetoskop (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Björndell, C.; Premberg, Å. Physicians’ experiences of video consultation with patients at a public virtual primary care clinic: A qualitative interview study. J. Prim. Health Care 2021, 39, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baluszek, J.B.; Wiig, S.; Myrnes-Hansen, K.V.; Brønnick, K.K. Specialized healthcare practitioners’ challenges in performing video consultations to patients in Nordic Countries—A systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lüchau, E.C.; Atherton, H.; Olesen, F.; Søndergaard, J.; Assing Hvidt, E. Interpreting technology: Use and non-use of doctor-patient video consultations in Danish general practice. Soc. Sci. Med. 2023, 334, 116215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Trotsenburg, M. Reproductive health in trans and gender diverse patients: Transgender medicine: Contextual trans gynecology. Reproduction 2024, 168, e240045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giudice, L.C.; Oskotsky, T.T.; Falako, S.; Opoku-Anane, J.; Sirota, M. Endometriosis in the era of precision medicine and impact on sexual and reproductive health across the lifespan and in diverse populations. FASEB J. 2023, 37, e23130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moeller, L.V.; Lindhardt, C.L.; Andersen, M.S.; Glintborg, D.; Ravn, P. Motivational interviewing in obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome—A pilot study. Gynecol. Endocrinol. Off. J. Int. Soc. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2019, 35, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, J. Det Handler om at Finde den Kloge Kombination. [It´s All About Finding the Smart Combination]. Ugeskr. Laege, July 1st 2022, 1. Available online: https://ugeskriftet.dk/nyhed/det-handler-om-finde-den-kloge-kombination (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Kulkarni, A.; Monu, N.; Ahsan, M.D.; Orakuwue, C.; Ma, X.; McDougale, A.; Frey, M.K.; Holcomb, K.; Cantillo, E.; Chapman-Davis, E. Patient and provider perspectives on telemedicine use in an outpatient gynecologic clinic serving a diverse, low-income population. J. Telemed. Telecare 2023, 31, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louise, L.C.; Kirstine, T.M. Communication Training at Medical School: A Quantitative Analysis. IgMIn Res. 2024, 2, 862–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, D.; Ostaszkiewicz, J.; Dunning, T.; Martin, P. The effectiveness of training interventions on nurses’ communication skills: A systematic review. Nurse Educ. Today 2020, 89, 104405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, E.R.; Stendal, K.; Gullslett, M.K. Implementation of eHealth Technology in Community Health Care: The complexity of stakeholder involvement. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vanstone, M.; Canfield, C.; Evans, C.; Leslie, M.; Levasseur, M.A.; MacNeil, M.; Pahwa, M.; Panday, J.; Rowland, P.; Taneja, S.; et al. Towards conceptualizing patients as partners in health systems: A systematic review and descriptive synthesis. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2023, 21, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Svendsen, M.T.; Tiedemann, S.N.; Andersen, K.E. Pros and cons of eHealth: A systematic review of the literature and observations in Denmark. SAGE Open Med. 2021, 9, 20503121211016179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Theme | Category | Subcategory |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-in situ training presents benefits and challenges | Communication | Interaction between theory and training |

| Before technical instruction | Combination of feedback and training | |

| New knowledge | Intercollegiate learning | |

| Learning skills | ||

| One learned a lot | ||

| Peer feedback is very effective |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lindhardt, C.L.; Feenstra, M.M.; Faurholt, H.; Andersen, L.R.; Thygesen, M.K. Piloting an In Situ Training Program in Video Consultations in a Gynaecological Outpatient Clinic at a University Hospital: A Qualitative Study of the Healthcare Professionals’ Perspectives. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1073. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091073

Lindhardt CL, Feenstra MM, Faurholt H, Andersen LR, Thygesen MK. Piloting an In Situ Training Program in Video Consultations in a Gynaecological Outpatient Clinic at a University Hospital: A Qualitative Study of the Healthcare Professionals’ Perspectives. Healthcare. 2025; 13(9):1073. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091073

Chicago/Turabian StyleLindhardt, Christina Louise, Maria Monberg Feenstra, Heidi Faurholt, Louise Rosenlund Andersen, and Marianne Kirstine Thygesen. 2025. "Piloting an In Situ Training Program in Video Consultations in a Gynaecological Outpatient Clinic at a University Hospital: A Qualitative Study of the Healthcare Professionals’ Perspectives" Healthcare 13, no. 9: 1073. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091073

APA StyleLindhardt, C. L., Feenstra, M. M., Faurholt, H., Andersen, L. R., & Thygesen, M. K. (2025). Piloting an In Situ Training Program in Video Consultations in a Gynaecological Outpatient Clinic at a University Hospital: A Qualitative Study of the Healthcare Professionals’ Perspectives. Healthcare, 13(9), 1073. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091073

_MD__MPH_PhD.png)