Social Media Addiction and Procrastination in Peruvian University Students: Exploring the Role of Emotional Regulation and Age Moderation

Abstract

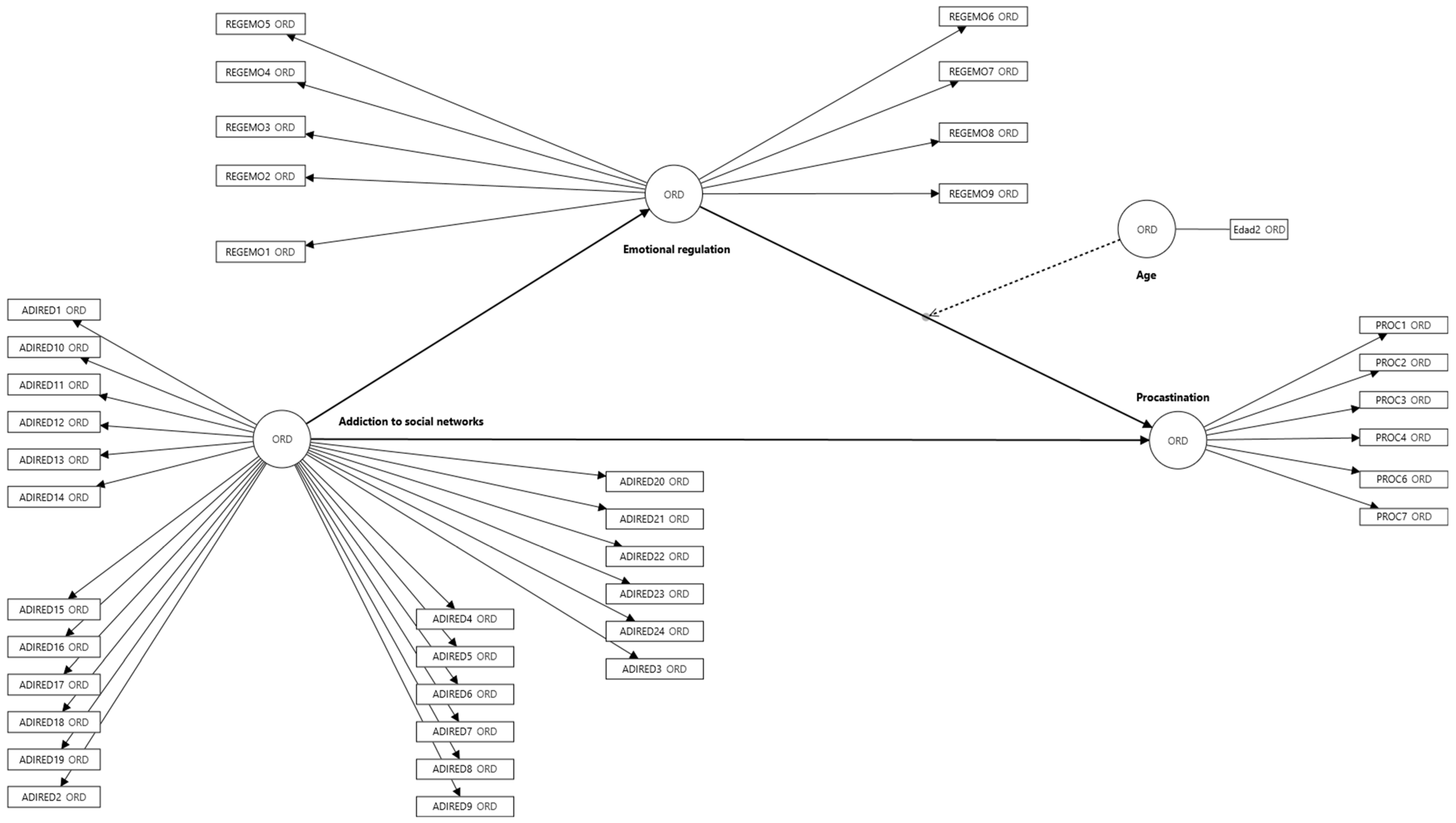

1. Introduction

1.1. Relationship Between Social Media Addiction and Irrational Procrastination

1.2. The Mediating Role of Emotional Regulation

1.3. The Moderating Role of Age

1.4. Research Objectives and Hypotheses

1.5. Importance of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Approach and Design

2.2. Population and Sample

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Instruments

2.5. Procedure and Statistical Analysis

2.6. Construct Quality Tests

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. The Relationship Between Social Media Addiction and Procrastination

4.2. The Role of Emotional Regulation in Procrastination

4.3. The Impact of Age on Procrastination

4.4. Emotional Regulation and Procrastination

4.5. The Moderating Influence of Age on Emotional Regulation and Procrastination

4.6. Social Media Addiction as a Key Mediator

4.7. The Role of Contextual Variables

4.8. The Impact of Social Media Content

4.9. Heterogeneity of Internet Users Based on Personality Traits

5. Conclusions

Limitations of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yana-Salluca, M.; Adco-Valeriano, D.Y.; Alanoca-Gutierrez, R.; Casa-Coila, M.D. Adicción a las redes sociales y la procrastinación académica en adolescentes peruanos en tiempos de coronavirus COVID-19. Rev. Electrón. Interuniv. Form. Profr. 2022, 25, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Arocha, A.; Camellón Curbelo, L.; Echemendía González, N. Redes Sociales: Imprescindible Herramienta En La Comunicación Universitaria. Pedagog. Soc. 2020, 23, 382–401. [Google Scholar]

- Escurra Mayaute, M.; Salas Blas, E. Construcción y Validación Del Cuestionario de Adicción a Redes Sociales (ARS). Liberabit 2014, 20, 73–91. [Google Scholar]

- Steel, P. The Nature of Procrastination: A Meta-Analytic and Theoretical Review of Quintessential Self-Regulatory Failure. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 133, 65–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Wang, H.; Ye, L.; Hao, G. Associations between Social Media Use and Sleep Quality in China: Exploring the Mediating Role of Social Media Addiction. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. 2024, 26, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual Jimeno, A.; Conejero López, S. Regulación Emocional y Afrontamiento: Aproximación Conceptual y Estrategias. [Emotional Regulation and Coping: Conceptual Approach and Strategies]. Rev. Mex. Psicol. 2019, 36, 74–83. [Google Scholar]

- Rozgonjuk, D.; Kattago, M.; Täht, K. Social Media Use in Lectures Mediates the Relationship between Procrastination and Problematic Smartphone Use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 89, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuckman, B.W. The Development and Concurrent Validity of the Procrastination Scale. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1991, 51, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirois, F.; Pychyl, T. Procrastination and the Priority of Short-Term Mood Regulation: Consequences for Future Self. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2013, 7, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.; Mou, Q.; Zheng, T.; Gao, F.; Zhong, Y.; Lu, Q.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, M. A Serial Mediation Model of Social Media Addiction and College Students’ Academic Engagement: The Role of Sleep Quality and Fatigue. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suárez-Perdomo, A.; Ruiz-Alfonso, Z.; Garcés-Delgado, Y. Profiles of Undergraduates’ Networks Addiction: Difference in Academic Procrastination and Performance. Comput. Educ. 2022, 181, 104459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Gao, H.; Xu, Y. The Mediating and Buffering Effect of Academic Self-Efficacy on the Relationship between Smartphone Addiction and Academic Procrastination. Comput. Educ. 2020, 159, 104001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J. Emotion Regulation: Affective, Cognitive, and Social Consequences. Psychophysiology 2002, 39, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, J.J.; John, O.P. Individual Differences in Two Emotion Regulation Processes: Implications for Affect, Relationships, and Well-Being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J.; Barrett, L.F. Emotion Generation and Emotion Regulation: One or Two Depends on Your Point of View. Emot. Rev. 2011, 3, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J. Emotion Regulation: Current Status and Future Prospects. Psychol. Inq. 2015, 26, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuss, D.J.; Griffiths, M.D. Social Networking Sites and Addiction: Ten Lessons Learned. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M.D. Disorders due to addictive behaviors: Further issues, debates, and controversies. J. Behav. Addict. 2022, 11, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, O.P.; Gross, J.J. Healthy and Unhealthy Emotion Regulation: Personality Processes, Individual Differences, and Life Span Development. J. Personal. 2004, 72, 1301–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, A.; Buiza, L. Adicción al Internet y Las Redes Sociales En Estudiantes de Primaria, Secundaria y Superior. Horiz. Rev. Investig. Cienc. Educ. 2024, 8, 449–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekpazar, A.; Kaya Aydın, G.; Aydın, U.; Beyhan, H.; Arı, E. Role of Instagram Addiction on Academic Performance among Turkish University Students: Mediating Effect of Procrastination. Comput. Educ. Open 2021, 2, 100049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, A.; Kaur, P.; Dhir, A.; Mäntymäki, M. Sleepless Due to Social Media? Investigating Problematic Sleep Due to Social Media and Social Media Sleep Hygiene. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 113, 106487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szawloga, T.; Soroka, K.; Siliwińska, M. Relationship between fear of missing-out and adolescents mental health. Med. Srod. 2024, 27, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yam, F.C.; Yıldırım, O.; Köksal, B. The Mediating and Buffering Effect of Resilience on the Relationship between Loneliness and Social Media Addiction among Adolescent. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 24080–24090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pychyl, T.A.; Sirois, F.M. Procrastination, Emotion Regulation, and Well-Being. In Procrastination, Health, and Well-Being; Elsevier Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2016; pp. 163–188. ISBN 978-0-12-802862-9. [Google Scholar]

- Danne, V.; Gers, B.; Altgassen, M. Is the Association of Procrastination and Age Mediated by Fear of Failure? J. Ration. Emotive Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2024, 42, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirois, F.M. Procrastination and Stress: A Conceptual Review of Why Context Matters. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, B.; Zhang, X. What Research Has Been Conducted on Procrastination? Evidence From a Systematical Bibliometric Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 809044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L.L. The Influence of a Sense of Time on Human Development. Science 2006, 312, 1913–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Vohs, K.D. Handbook of Self-Regulation: Research, Theory, and Applications; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-1-57230-991-3. [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen, L.L. Social and Emotional Patterns in Adulthood: Support for Socioemotional Selectivity Theory. Psychol. Aging 1992, 7, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Deursen, A.J.A.M.; Bolle, C.L.; Hegner, S.M.; Kommers, P.A.M. Modeling Habitual and Addictive Smartphone Behavior: The Role of Smartphone Usage Types, Emotional Intelligence, Social Stress, Self-Regulation, Age, and Gender. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 45, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedón Cando, J.C.; Flores Hernández, V.F. Procrastinación académica y riesgo de adicción a las redes sociales e internet en estudiantes de bachillerato: Academic procrastination and risk of addiction to social networks and internet in high school students. LATAM Rev. Latinoam. Cienc. Soc. Humanid. 2023, 4, 598–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalaya Laureano, C.; García Ampudia, L. Procrastinación: Revisión Teórica. Rev. Investig. Psicol. 2019, 22, 363–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Guzmán, R.L.; Cisneros-Chavez, B.C. Adicción a Redes Sociales y Procrastinación Académica En Estudiantes Universitarios. Nuevas Ideas Inform. Educ. 2019, 15, 114–120. [Google Scholar]

- Çuhadar, A.; Er, Y.; Demirel, M. Relación del uso de redes sociales y gestión del ocio en estudiantes universitarios. Apunt. Univ. 2022, 12, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadkarni, A.; Hofmann, S.G. Why Do People Use Facebook? Personal. Individ. Differ. 2012, 52, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, E.C.; Williams, I.R.; Tomyn, A.J.; Sanci, L. Social Media Use among Australian University Students: Understanding Links with Stress and Mental Health. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2024, 14, 100398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.-H.; Cui, Y.; Wang, L.; Ye, J.-N. The Relationships between the Short Video Addiction, Self-Regulated Learning, and Learning Well-Being of Chinese Undergraduate Students. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. 2024, 26, 805–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ato, M.; López, J.J.; Benavente, A. Un Sistema de Clasificación de Los Diseños de Investigación En Psicología. An. Psicol. 2013, 29, 1038–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandín, B.; Chorot, P.; Valiente, R. Transdiagnóstico: Nueva frontera en psicología clínica. Rev. Psicopatol. Psicol. Clín. 2012, 17, 185–203. [Google Scholar]

- Padrós Blázquez, F.; Guzmán, M.E. Estructura Factorial y Fiabilidad de La “Escala de Procrastinación Irracional” (IPS) En México. [Factorial Structure and Reliability of the Irrational Procrastination Scale (IPS) in Mexico]. Behav. Psychol. 2022, 30, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Méndez, C.A.; Romero-Méndez, D.L. Procrastinación académica, adicción a redes sociales y funciones ejecutivas: Un estudio de autorreporte en adolescentes. Rev. Panam. Pedagog. 2024, 38, 110–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyngs, U.; Lukoff, K.; Slovak, P.; Seymour, W.; Webb, H.; Jirotka, M.; Zhao, J.; Kleek, M.V.; Shadbolt, N. “I Just Want to Hack Myself to Not Get Distracted”: Evaluating Design Interventions for Self-Control on Facebook. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 April 2020; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Klibert, J.; LeLeux-LaBarge, K.; Tarantino, N.; Yancey, T.; Lamis, D.A. Procrastination and Suicide Proneness: A Moderated-Mediation Model for Cognitive Schemas and Gender. Death Stud. 2016, 40, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orco León, E.; Huamán Saldívar, D.; Torres Torreblanca, J.; Mejía, C.; Corrales Reyes, I.E. Asociación Entre Procrastinación y Estrés Académico En Estudiantes Peruanos de Segundo Año de Medicina. Horiz. Rev. Investig. Cienc. Educ. 2022, 41, e704. [Google Scholar]

- Alarcón Allaín, G.; Salas Blas, E. Adicción a redes sociales e inteligencia emocional en estudiantes de educación superior técnica. Health Addict. Salud Drog. 2022, 22, 152–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán Brand, V.A.; Gélvez García, L.E. Adicción o uso problemático de las redes sociales online en la población adolescente. Una revisión sistemática. Psicoespacios 2023, 17, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.; Pedras, S.; Inman, R.A.; Ramalho, S.M. Latent Profiles of Emotion Regulation among University Students: Links to Repetitive Negative Thinking, Internet Addiction, and Subjective Wellbeing. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1272643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, A.; Clariana, M. Procrastinación en Estudiantes Universitarios: Su Relación con la Edad y el Curso Académico. Rev. Colomb. Psicol. 2017, 26, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Morales, J. Procrastination: A Review of Scales and Correlates. Rev. Iberoam. Diag. Eval. Psicol. 2018, 51, 43–60. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, S.M.; Wegmann, E.; Stolze, D.; Brand, M. Maximizing Social Outcomes? Social Zapping and Fear of Missing out Mediate the Effects of Maximization and Procrastination on Problematic Social Networks Use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 107, 106296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovan, A.; Yıldırım, M.; Gülbahçe, A. The Relationship between Fear of Missing out and Social Media Addiction among Turkish Muslim Students: A Serial Mediation Model through Self-Control and Responsibility. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2024, 10, 101084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J.; Jazaieri, H. Emotion, Emotion Regulation, and Psychopathology: An Affective Science Perspective. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 2, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wypych, M.; Matuszewski, J.; Dragan, W.Ł. Roles of Impulsivity, Motivation, and Emotion Regulation in Procrastination—Path Analysis and Comparison Between Students and Non-Students. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ros, R.; Pérez-González, F.; Tomás, J.M.; Sancho, P. Effects of Self-Regulated Learning and Procrastination on Academic Stress, Subjective Well-Being, and Academic Achievement in Secondary Education. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 26602–26616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Olivares, R.; Lucena, V.; Pino, M.J.; Herruzo, J. Análisis de comportamientos relacionados con el uso/abuso de Internet, teléfono móvil, compras y juego en estudiantes universitarios. Adicciones 2010, 22, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olhaberry, M.; Sieverson, C. Desarrollo Socio-Emocional Temprano y Regulación Emocional. Rev. Méd. Clín. Condes 2022, 33, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Vilugron, G.; Saavedra, E.; Rojas-Mora, J.; Riquelme, E. Incidencia de Los Espacios Escolares Sobre La Regulación Emocional y El Aprendizaje En Contextos de Diversidad Social y Cultural. Rev. Estud. Exp. Educ. 2024, 22, 142–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, M.; Ebert, D.D.; Lehr, D.; Sieland, B.; Berking, M. Overcome Procrastination: Enhancing Emotion Regulation Skills Reduce Procrastination. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2016, 52, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreta-Herrera, R.; Durán Rodríguez, T.; Villegas Villacrés, N. Regulación Emocional y Rendimiento Como Predictores de La Procrastinación Académica En Estudiantes Universitarios. Rev. Psicol. Educ. 2024, 13, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Tenorio, A.L.; Oyanguren-Casas, N.A.; Reyes-González, A.A.I.; Zegarra, Á.C.; Cueva, M.E. El rol moderador de la procrastinación sobre la relación entre el estrés académico y bienestar psicológico en estudiantes de pregrado. Propós. Represent. 2021, 9, e1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wartberg, L.; Thomasius, R.; Paschke, K. The Relevance of Emotion Regulation, Procrastination, and Perceived Stress for Problematic Social Media Use in a Representative Sample of Children and Adolescents. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 121, 106788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, L. Adicción a las redes sociales, procrastinación académica y cansancio emocional en estudiantes de una universidad privada de Lima, Perú. RIEE Rev. Int. Estud. Educ. 2022, 22, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García del Castillo, J.A.; del Castillo-López, Á.G.; Dias, P.C.; García-Castillo, F. Conceptualización del comportamiento emocional y la adicción a las redes sociales virtuales. Health Addict. Salud Drog. 2019, 19, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi Liu, Q.; Kui Zhou, Z.; Juan Yang, X.; Feng Niu, G. Upward social comparison on social network sites and depressive symptoms: A moderated mediation model of self-esteem and optimism. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2018, 113, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellana Rosell, M.; Sánchez-Carbonell, X.; Graner Jordana, C.; Beranuy Fargues, M. El adolescente ante las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación: Internet, móvil y videojuegos. Papeles Psicol. 2007, 28, 196–204. [Google Scholar]

- Echeburúa, E.; Del Corral, P. Adicción a las nuevas tecnologías y a las redes sociales en jóvenes: Un nuevo reto. Adicciones 2010, 22, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rial, A.; Gómez, P.; Braña, T.; Varela, J. Actitudes, Percepciones y Uso de Internet y Las Redes Sociales Entre Los Adolescentes de La Comunidad Gallega (España). An. Psicol. 2014, 30, 642–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreiro, S.G.; Folgar, M.I.; Salgado, P.G.; Boubeta, A.R. Uso problemático de Internet y adolescentes: El deporte sí importa (Problematic Internet use and adolescents: Sport does matter). Retos 2017, 31, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llamas Salguero, F.; Pagador Otero, I. Estudio sobre las redes sociales y su implicación en la adolescencia. Enseñanza Teach. Rev. Interuniv. Didáctica 2014, 1, 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Subrahmanyam, K.; Šmahel, D. Digital Youth: The Role of Media in Development; Springer Science + Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4419-6277-5. [Google Scholar]

| Relation | Author | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Social Media Addiction—Irrational Procrastination | [4] | The model provides a comprehensive explanation of irrational procrastination as the search for immediate gratification and the escape from emotional discomfort, using social networks as a way to fill emotional gaps, making it difficult to complete important tasks. |

| Social media addiction: emotional regulation | [17] | The model illustrates how the relationship between social media addiction and emotional regulation is interconnected, with the compulsive use of social media to regulate emotions, reinforcing addictive behavior. |

| Age—Irrational Procrastination | [4] | The Temporal Procrastination Model explains that as people age, their perception of time and their ability to regulate motivation change, leading to a decrease in procrastination in many cases. |

| Emotional Regulation—Irrational Procrastination | [25] | The model highlights how procrastination is used as a mechanism to regulate emotions, especially in the context of anxiety and stress. |

| Age × Emotional regulation: Irrational Procrastination | [29] | The Selective Socioemotional Development Model suggests that as people age, their priorities and motivations change, which affects how they regulate emotions and how they manage procrastination. |

| Social media addiction—emotional regulation—irrational procrastination | [4,30,31] | Information Processing and Self-Regulation Model, combined with the Socio-Emotional Development Theory and the Procrastination Theory perspective. It stresses that these variables are particularly interrelated, especially in the early stages of life, when self-regulation skills are not fully developed. |

| Age—Social Media Addictionvan | [32] | Age is related to addictive smartphone behavior, including problematic social media use. |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability (rho_a) | Composite Reliability (rho_c) | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network addiction | 0.954 | 0.963 | 0.959 | 0.502 |

| Procrastination | 0.850 | 0.853 | 0.888 | 0.570 |

| Emotional regulation | 0.865 | 0.923 | 0.884 | 0.583 |

| Network Addiction | Age | Procrastination | Emotional Regulation | Age × Emotional Regulation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network addiction | |||||

| Age | 0.136 | ||||

| Procrastination | 0.259 | 0.034 | |||

| Emotional regulation | 0.322 | 0.067 | 0.159 | ||

| Age × Emotional regulation | 0.086 | 0.087 | 0.163 | 0.124 |

| Variable | Category | Absolute Frequency | Percentage |

| Sex | Female | 261 | 80.06% |

| Male | 65 | 19.94% | |

| Cycle | 10 | 85 | 26.07% |

| 9 | 45 | 13.80% | |

| 8 | 45 | 13.80% | |

| 11 | 44 | 13.50% | |

| 7 | 43 | 13.19% | |

| 6 | 27 | 8.28% | |

| 2 | 17 | 5.21% | |

| 4 | 6 | 1.84% | |

| 5 | 5 | 1.53% | |

| Age | 18–22 years old | 164 | 50.31% |

| 23–27 years old | 113 | 34.66% | |

| 28–32 years of age | 24 | 7.36% | |

| 33–37 years | 15 | 4.60% | |

| 38 years and older | 10 | 3.07% | |

| Place of origin | Trujillo | 157 | 48.16% |

| Cajamarca | 41 | 12.58% | |

| Huamachuco | 21 | 6.44% | |

| Lima | 8 | 2.45% | |

| Other | 29 | 2.15% | |

| Descriptive results | |||

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

| Cognitive Reappraisal | Low | 103 | 30.10% |

| Medium | 156 | 45.60% | |

| High | 83 | 24.30% | |

| Emotional Suppression | Low | 83 | 24.30% |

| Medium | 171 | 50.00% | |

| High | 88 | 25.70% | |

| Social Media Addiction | Low | 136 | 39.80% |

| Medium | 171 | 50.00% | |

| High | 35 | 10.20% | |

| Procrastination | Low | 95 | 27.80% |

| Medium | 171 | 50.00% | |

| High | 76 | 22.20% | |

| R Square | Adjusted R-Squared | F Square | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Procrastination | 0.095 | 0.084 | 0.137 |

| Emotional regulation | 0.120 | 0.117 | 0.079 |

| Variable | Range VIF | Media VIF | Critical Elements (VIF > 3.0) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internet Addiction (ADIRED) | 1.238–4.036 | 2.627 | ADIRED7 (4.036), ADIRED19 (3.195), ADIRED11 (3.107), ADIRED10 (3.085), ADIRED6 (3.000) |

| Procrastination (PROC) | 1.515–2.464 | 1.868 | None |

| Emotional regulation (REGEMO) | 1.863–3.238 | 2.41 | REGEMO4 (3.238) |

| Saturated Model | Estimated Model | |

|---|---|---|

| SRMR | 0.076 | 0.076 |

| d_ULS | 4.680 | 4.708 |

| d_G | 1.453 | 1.454 |

| Chi-squared | 2481.036 | 2482.803 |

| NFI | 0.713 | 0.712 |

| Hypothesis | Type of Hypothesis. | Original Sample (O) | Standard Deviation | Statistics t | p-Values | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social media addiction -> Procrastination | Direct | 0.289 | 0.067 | 4.275 | 0.000 | Reject the null hypothesis |

| Social media addiction -> Emotional regulation | Direct | −0.347 | 0.068 | 5.068 | 0.000 | Reject the null hypothesis |

| Age -> Procrastination | Direct | 0.006 | 0.058 | 0.111 | 0.912 | Maintain the null hypothesis |

| Emotional regulation -> Procrastination | Direct | 0.137 | 0.091 | 1.498 | 0.134 | Maintain the null hypothesis |

| Age × Emotional regulation -> Procrastination | Moderation | 0.158 | 0.074 | 2.139 | 0.033 | Reject the null hypothesis |

| Social media addiction -> emotional regulation -> procrastination | Mediation | −0.047 | 0.035 | 1.347 | 0.178 | Maintain the null hypothesis |

| Addiction to social networks -> Procastination | Total | 0.241 | 0.062 | 4.175 | 0.000 | Reject the null hypothesis |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fuentes Chavez, S.E.; Vera-Calmet, V.G.; Aguilar-Armas, H.M.; Yglesias Alva, L.A.; Arbulú Ballesteros, M.A.; Alegria Silva, C.E. Social Media Addiction and Procrastination in Peruvian University Students: Exploring the Role of Emotional Regulation and Age Moderation. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091072

Fuentes Chavez SE, Vera-Calmet VG, Aguilar-Armas HM, Yglesias Alva LA, Arbulú Ballesteros MA, Alegria Silva CE. Social Media Addiction and Procrastination in Peruvian University Students: Exploring the Role of Emotional Regulation and Age Moderation. Healthcare. 2025; 13(9):1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091072

Chicago/Turabian StyleFuentes Chavez, Sandra Elizabeth, Velia Graciela Vera-Calmet, Haydee Mercedes Aguilar-Armas, Lucy Angélica Yglesias Alva, Marco Agustín Arbulú Ballesteros, and Cristian Edgardo Alegria Silva. 2025. "Social Media Addiction and Procrastination in Peruvian University Students: Exploring the Role of Emotional Regulation and Age Moderation" Healthcare 13, no. 9: 1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091072

APA StyleFuentes Chavez, S. E., Vera-Calmet, V. G., Aguilar-Armas, H. M., Yglesias Alva, L. A., Arbulú Ballesteros, M. A., & Alegria Silva, C. E. (2025). Social Media Addiction and Procrastination in Peruvian University Students: Exploring the Role of Emotional Regulation and Age Moderation. Healthcare, 13(9), 1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091072