Effect of Diabetes Self-Efficacy on Coping Strategy: Self-Stigma’s Mediating Effect

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Independent Variable: Self-Efficacy

2.3.2. Dependent Variable: Coping Strategy

2.3.3. Mediating Variable: Self-Stigma

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Ethical Consideration

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics and Degree of Study Variables

3.2. Difference Between Self-Stigma, Self-Efficacy, and Coping Strategy According to General Characteristics

3.3. Correlation Between Self-Stigma, Self-Efficacy, and Coping Strategy

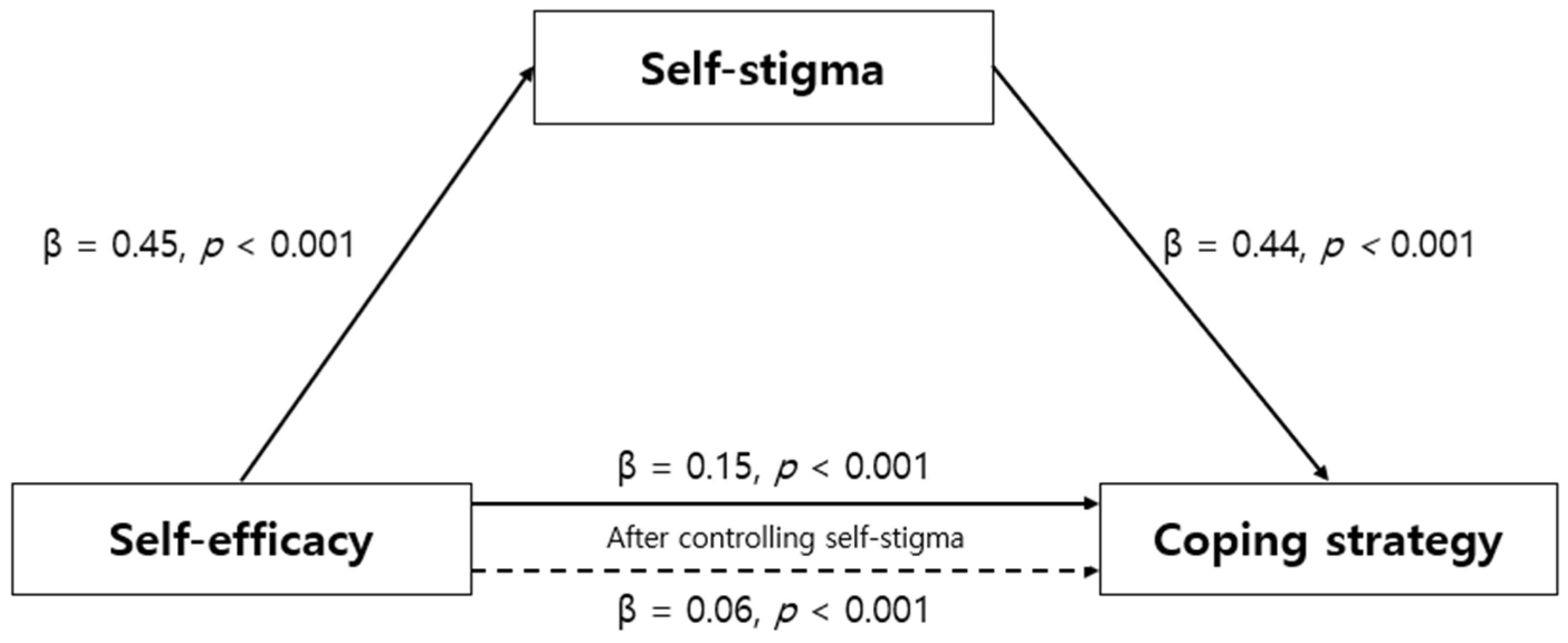

3.4. Mediating Effect of Self-Stigma on Relationship Between Self-Efficacy and Coping Strategy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Diabetes Federation, IDF. Available online: https://idf.org/about-diabetes/diabetes-facts-figures/ (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Korean Diabetes Association. Diabetes Fact Sheet in Korea 2024; Korean Diabetes Association: Seoul, The Republic of Korea, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency, KDCA. Available online: https://health.kdca.go.kr/healthinfo/biz/health/gnrlzHealthInfo/gnrlzHealthInfo/gnrlzHealthInfoView.do?cnnts_sn=2351 (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Papatheodorou, K.; Banach, M.; Bekiari, E.; Rizzo, M.; Edmonds, M. Complications of diabetes 2017. J. Diabetes Res. 2018, 2018, 3086167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, P.; Khullar, S.; Singh, M.; Kaur, G.; Mastana, S. Diabetes to cardiovascular disease: Is depression the potential missing link? Med. Hypotheses 2015, 84, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1986, 4, 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Amer, R.; Ramjan, L.; Glew, P.; Randall, S.; Salamonson, Y. Self-efficacy, depression, and self-care activities in adult Jordanians with type 2 diabetes: The role of illness perception. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2016, 37, 744–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, P.; Maki, A.; Montanaro, E.; Avishai-Yitshak, A.; Bryan, A.; Klein, W.M.; Miles, E.; Rothman, A.J. The impact of changing attitudes, norms, and self-efficacy on health-related intentions and behavior: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2016, 35, 1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukarno, A.; Bahtiar, B. The effectiveness of cognitive behavior therapy on psychological stress, physical health, and self-care behavior among diabetes patients: A systematic review. Health Educ. Health Promot. 2022, 10, 531–537. [Google Scholar]

- Zaheri, H.; Najar, S.; Abbaspoor, Z. Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral stress management on psychological stress and glycemic control in gestational diabetes: A randomized controlled trial. J. Matern. -Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017, 30, 1378–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, M.A.; Theeke, L.A. A systematic review of the relationships among psychosocial factors and coping in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int. J. Nurs Sci. 2019, 6, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hapunda, G. Coping strategies and their association with diabetes specific distress, depression and diabetes self-care among people living with diabetes in Zambia. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2022, 22, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenmakers, E.C.; Van Tilburg, T.G.; Fokkema, T. Problem-focused and emotion-focused coping options and loneliness: How are they related? Eur. J. Ageing. 2015, 12, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, M.H.; Lipsky, L.M.; Dempster, K.W.; Liu, A.; Nansel, T.R. I should but I can’t: Controlled motivation and self-efficacy are related to disordered eating behaviors in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 59, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Novitasari, E.; Hamid, A.Y.S. The relationships between body image, self-efficacy, and coping strategy among Indonesian adolescents who experienced body shaming. Enfermería Clínica. 2021, 31, S185–S189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, K.; Song, Y. Self-stigma among Korean patients with diabetes: A concept analysis. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 1794–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, E.; Scior, K.; Avramides, K.; Crane, L. A systematic review on autistic people’s experiences of stigma and coping strategies. Autism Res. 2022, 15, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorig, K.; Stewart, A.; Ritter, P.; Gonzalez, V.; Laurent, D.; Lynch, J. Outcome Measures for Health Education and Other Health Care Interventions; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, S.J.; Song, M.; Im, E.O. Psychometric evaluation of the Korean version of the Diabetes Self-efficacy S ale among South Korean older adults with type 2 diabetes. J. Clin. Nurs. 2014, 23, 2121–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, G. The Diabetes Coping Measure: A measure of cognitive and behavioral coping specific to diabetes. In Handbook Psychology and Diabetes: A Guide to Psychological Measurement in Diabetes Research and Practice; Harwood: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Byun, S.H. Structural Equation Modeling for Quality of Life with Diabetes: Associated with Diabetes Locus of Control, Social Support, Self-Efficacy, and Coping Strategy. Unpublished. Ph.D. Thesis, Inje University, Busan, Republic of Korea, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, K.; Song, Y. Development and validation of the self-stigma scale in people with diabetes. Nurs. Open. 2021, 8, 1089–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banu, B.; Khan, M.M.H.; Ali, L.; Barnighausen, T.; Sauerborn, R.; Souares, A. Pattern and predictors of non-adherence to diabetes self-management recommendations among patients in peripheral district of Bangladesh. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2024, 29, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J.H.; Jin, H.; Park, J.U. Association between socioeconomic position and diabetic foot ulcer outcomes: A population-based cohort study in South Korea. BMC Public. Health 2021, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.H. 2024 Policy Revision for Support of Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus Patients. J. Korean Diabetes 2024, 25, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Deng, H.; Hu, N.; Huang, W.; Wang, H.; Liu, L.; Chai, J.; Li, Y. The relationship between self-stigma and quality of life in long-term hospitalized patients with schizophrenia: A cross-sectional study. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1366030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aktu, Y.; Aras, E. Adaptation and validation of the Parents’ Self-stigma Scale into Turkish and its association with parenting stress and parental self-efficacy. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakan, G.; Inci, F.H. Predictor of self-efficacy in individuals with chronic disease: Stress-coping strategies. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021, 30, 874–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.H.; Lin, C.C.; Chen, S.Y.; Hsu, H.C.; Huang, C.L. The impact of self-stigma, role strain, and diabetes distress on quality of life and glycemic control in women with diabetes: A 6-month prospective study. Biol Res Nurs. 2021, 23, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Na, H. The relationship between internalized stigma and treatment adherence in community-dwelling individuals with mental illness: The mediating effect of self-efficacy. J. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2016, 25, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, A.; Fujimaki, Y.; Fujimori, S.; Isogawa, A.; Onishi, Y.; Suzuki, R.; Yamauchi, T.; Ueki, K.; Kadowaki, T.; Hashimoto, H. Association between self-stigma and self-care behaviors in patients with type 2 diabetes: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care. 2016, 4, e000156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keum, H.; Suh, S.; Han, S. The Influence of Self-management Knowledge and Distress on Diabetes Management Self-efficacy in Type 2 Diabetes Patients. J. Korea Acad. -Ind. Coop. Soc. 2020, 21, 498–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataya, J.; Soqia, J.; Albani, N.; Tahhan, N.K.; Alfawal, M.; Elmolla, O.; Albaldi, A.; Alsheikh, R.A.; Kabalan, Y. The role of self-efficacy in managing type 2 diabetes and emotional well-being: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babazadeh, T.; Lotfi, Y.; Ranjbaran, S. Predictors of self-care behaviors and glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Front. Public. Health 2023, 10, 1031655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong-Artborirak, P.; Seangpraw, K.; Boonyathee, S.; Auttama, N.; Winaiprasert, P. Health literacy, self-efficacy, self-care behaviors, and glycemic control among older adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A cross-sectional study in Thai communities. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, B.; Jiang, X. The mediating role of diabetes stigma and self-efficacy in relieving diabetes distress among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A multicenter cross-sectional study. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1147101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Categories | M ± SD or n (%) | Min–Max |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 100 (52.9) | |

| Female | 89 (47.1) | ||

| Age (yr) | 67.42 ± 12.51 | 32.00–94.00 | |

| <55 | 31 (14.4) | ||

| 55~64 | 42 (22.2) | ||

| 65~74 | 59 (31.2) | ||

| ≥75 | 57 (30.2) | ||

| Educational level | Elementary school or lower | 48 (25.4) | |

| Middle school | 37 (19.6) | ||

| High school | 63 (33.3) | ||

| ≥University or higher | 41 (21.7) | ||

| Living type | Alone | 33 (17.5) | |

| With family | 156 (82.5) | ||

| Perceived economic status | Satisfied | 35 (18.5) | |

| Moderate | 123 (65.1) | ||

| Unsatisfied | 31 (16.4) | ||

| Duration of diabetes (yrs) | 12.40 ± 9.95 | 1.00–43.00 | |

| ≤10 | 96 (50.8) | ||

| 11~20 | 53 (28.0) | ||

| ≥21 | 40 (21.2) | ||

| Type of hospital used for treatment | Public health center | 45 (23.8) | |

| Hospital | 116 (61.4) | ||

| Clinic | 28 (14.8) | ||

| Type of medication | PO | 166 (87.8) | |

| Insulin | 7 (3.7) | ||

| PO + Insulin | 16 (8.5) | ||

| Having complications | Yes | 28 (14.8) | |

| No | 161 (85.2) | ||

| Having received education on diabetes | Yes | 148 (78.3) | |

| No | 41 (21.7) | ||

| Self-efficacy | 6.29 ± 10.80 | 1.88–10.00 | |

| Coping strategy | 2.72 ± 0.82 | 1.00–5.00 | |

| Self-stigma | 2.84 ± 0.54 | 1.38–4.14 | |

| Characteristics | Categories | Self-Efficacy | Coping Strategy | Self-Stigma | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SD | t or F | p Scheffe | M ± SD | t or F | p Scheffe | M ± SD | t or F | p Scheffe | ||

| Gender | Male | 6.26 ± 1.95 | −0.24 | 0.812 | 2.83 ± 0.55 | −0.45 | 0.656 | 2.65 ± 0.80 | −1.27 | 0.207 |

| Female | 6.32 ± 1.61 | 2.86 ± 0.53 | 2.80 ± 0.85 | |||||||

| Age (yr) | <55 a | 6.03 ± 1.70 | 1.08 | 0.358 | 2.77 ± 0.57 | 1.96 | 0.122 | 2.57 ± 0.86 | 2.48 | 0.063 |

| 55~64 b | 6.45 ± 1.78 | 2.71 ± 0.56 | 2.48 ± 0.89 | |||||||

| 65~74 c | 6.55 ± 1.76 | 2.95 ± 0.52 | 2.85 ± 0.75 | |||||||

| ≥75 d | 6.05 ± 1.88 | 2.87 ± 0.52 | 2.84 ± 0.79 | |||||||

| Educational level | Elementary school a | 5.94 ± 1.80 | 2.45 | 0.065 | 2.94 ± 0.42 | 5.14 | 0.002 a, b, c > d | 2.88 ± 0.69 | 7.78 | <0.001 a, b, c > d |

| Middle school b | 6.16 ± 1.87 | 2.94 ± 0.52 | 2.96 ± 0.78 | |||||||

| High school c | 6.22 ± 1.74 | 2.89 ± 0.58 | 2.80 ± 0.83 | |||||||

| ≥University d | 6.92 ± 1.71 | 2.56 ± 0.54 | 2.21 ± 0.82 | |||||||

| Living type | Yes | 6.01 ± 1.84 | 0.94 | 0.352 | 2.90 ± 0.59 | 0.62 | 0.539 | 2.81 ± 0.89 | 0.65 | 0.521 |

| No | 6.35 ± 1.79 | 2.83 ± 0.53 | 2.70 ± 0.81 | |||||||

| Perceived Economic status | Satisfied a | 7.36 ± 1.62 | 11.17 | <0.001 a > b,c | 2.47 ± 0.60 | 13.51 | <0.001 a < b, c | 2.13 ± 0.73 | 14.47 | <0.001 a < b < c |

| Moderate b | 6.21 ± 7.78 | 2.88 ± 0.50 | 2.80 ± 0.81 | |||||||

| Unsatisfied c | 5.41 ± 1.46 | 3.10 ± 0.42 | 3.08 ± 0.62 | |||||||

| Duration of diabetes (yr) | ≤10 a | 6.41 ± 1.67 | 0.43 | 0.648 | 2.82 ± 0.56 | 0.45 | 0.638 | 2.68 ± 0.83 | 1.73 | 0.181 |

| 11~20 b | 6.22 ± 1.96 | 2.90 ± 0.53 | 2.63 ± 0.80 | |||||||

| ≥21 c | 6.11 ± 1.90 | 2.81 ± 0.52 | 2.93 ± 0.82 | |||||||

| Type of hospital | Public health center a | 5.37 ± 1.53 | 10.46 | <0.001 a < b, c | 3.18 ± 0.43 | 16.27 | <0.001 a > b,c | 3.16 ± 0.56 | 15.44 | <0.001 a > b > c |

| Hospital b | 6.44 ± 1.77 | 2.78 ± 0.51 | 2.69 ± 0.83 | |||||||

| Clinic c | 7.15 ± 1.72 | 2.54 ± 0.55 | 2.14 ± 0.78 | |||||||

| Type of medication | PO a | 6.27 ± 1.81 | 0.15 | 0.861 | 2.84 ± 0.53 | 1.41 | 0.247 | 2.68 ± 0.79 | 2.03 | 0.134 |

| Insulin b | 6.52 ± 1.98 | 3.13 ± 0.59 | 3.23 ± 0.92 | |||||||

| PO + insulin c | 6.47 ± 1.62 | 2.73 ± 0.59 | 2.92 ± 1.02 | |||||||

| Having a complications | Yes | 5.97 ± 1.66 | 1.09 | 0.285 | 2.99 ± 0.51 | −1.61 | 0.115 | 3.12 ± 0.81 | −2.81 | 0.008 |

| No | 6.35 ± 1.82 | 2.82 ± 0.54 | 2.65 ± 0.81 | |||||||

| Experience of diabetes education | Yes | 6.32 ± 1.78 | −0.46 | 0.648 | 2.86 ± 0.56 | −0.94 | 0.350 | 2.78 ± 0.86 | −1.70 | 0.091 |

| No | 6.17 ± 1.88 | 2.78 ± 0.46 | 2.53 ± 0.67 | |||||||

| 1 r (p) | 2 r (p) | 3 r (p) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Self-efficacy | 1 | ||

| 2. Coping strategy | −0.52 (<0.001) | ||

| 3. Self-stigma | −0.45 (<0.001) | 0.78 (<0.001) |

| Step | Independent Variables | Dependent Variables | B | SE | β | t (p) | Adj. R2 | F (p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Self-efficacy | Self-stigma | 0.21 | 0.03 | 0.45 | 6.95 (<0.001) | 0.201 | 45.34 (<0.001) |

| 2 | Self-efficacy | Coping strategy | 0.15 | 0.01 | 0.52 | 17.73 (<0.001) | 0.268 | 69.74 (<0.001) |

| 3 | Self-efficacy | Coping strategy | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.21 | 4.29 (<0.001) | 0.640 | 167.92 (<0.001) |

| Self-stigma | Coping strategy | 0.44 | 0.03 | 0.68 | 13.93 (<0.001) | |||

| Sobel test; Z = 12.51 (p < 0.001) | ||||||||

| Effect | Boot SE | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | ||

| 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, H.; Park, S.; Seo, K. Effect of Diabetes Self-Efficacy on Coping Strategy: Self-Stigma’s Mediating Effect. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1066. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091066

Lee H, Park S, Seo K. Effect of Diabetes Self-Efficacy on Coping Strategy: Self-Stigma’s Mediating Effect. Healthcare. 2025; 13(9):1066. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091066

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Hyunjin, Seyeon Park, and Kawoun Seo. 2025. "Effect of Diabetes Self-Efficacy on Coping Strategy: Self-Stigma’s Mediating Effect" Healthcare 13, no. 9: 1066. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091066

APA StyleLee, H., Park, S., & Seo, K. (2025). Effect of Diabetes Self-Efficacy on Coping Strategy: Self-Stigma’s Mediating Effect. Healthcare, 13(9), 1066. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091066