Exploring Factors Associated with Health Status and Dietary Supplement Use Among Portuguese Adults: A Cross-Sectional Online Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

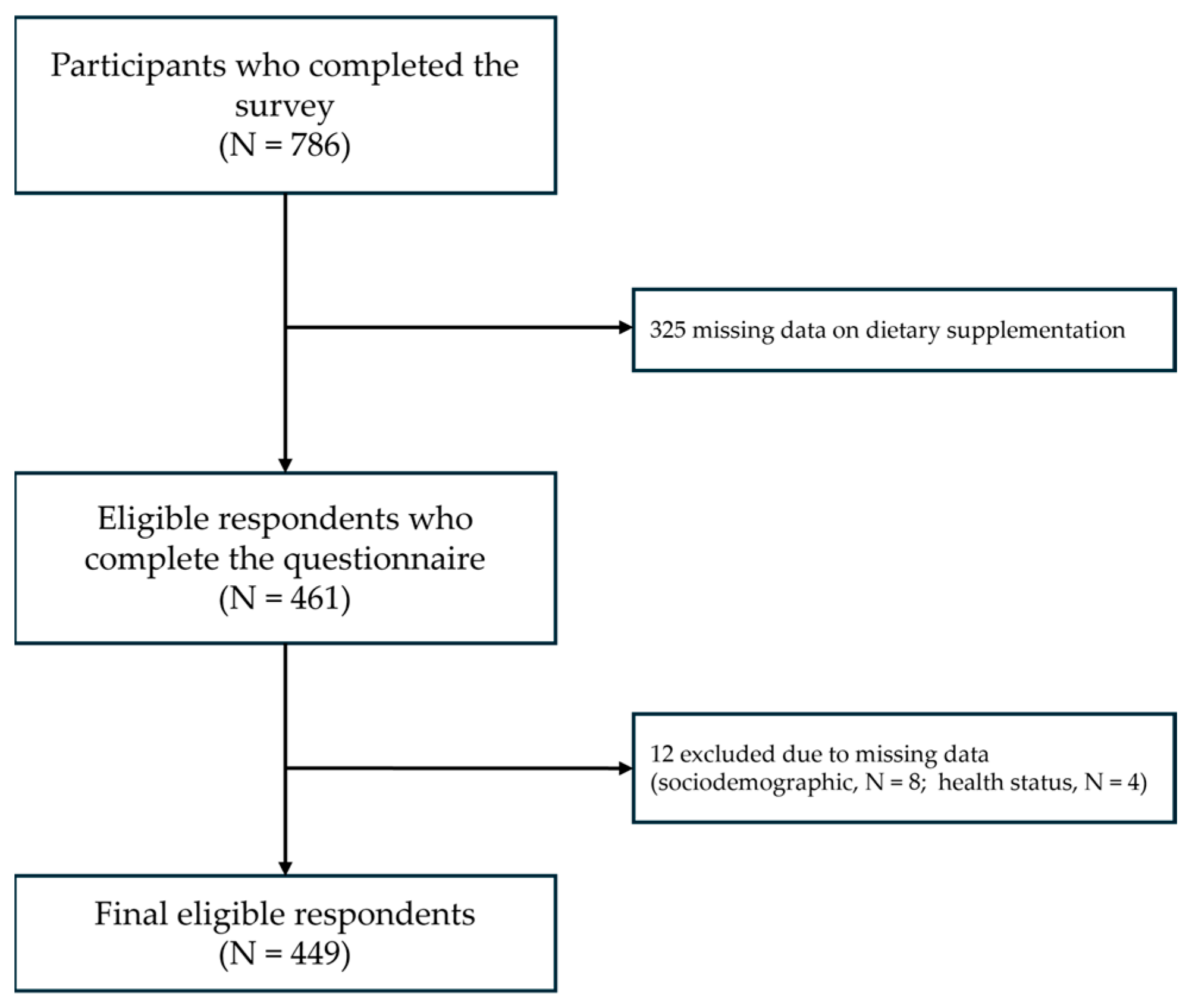

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Variables

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

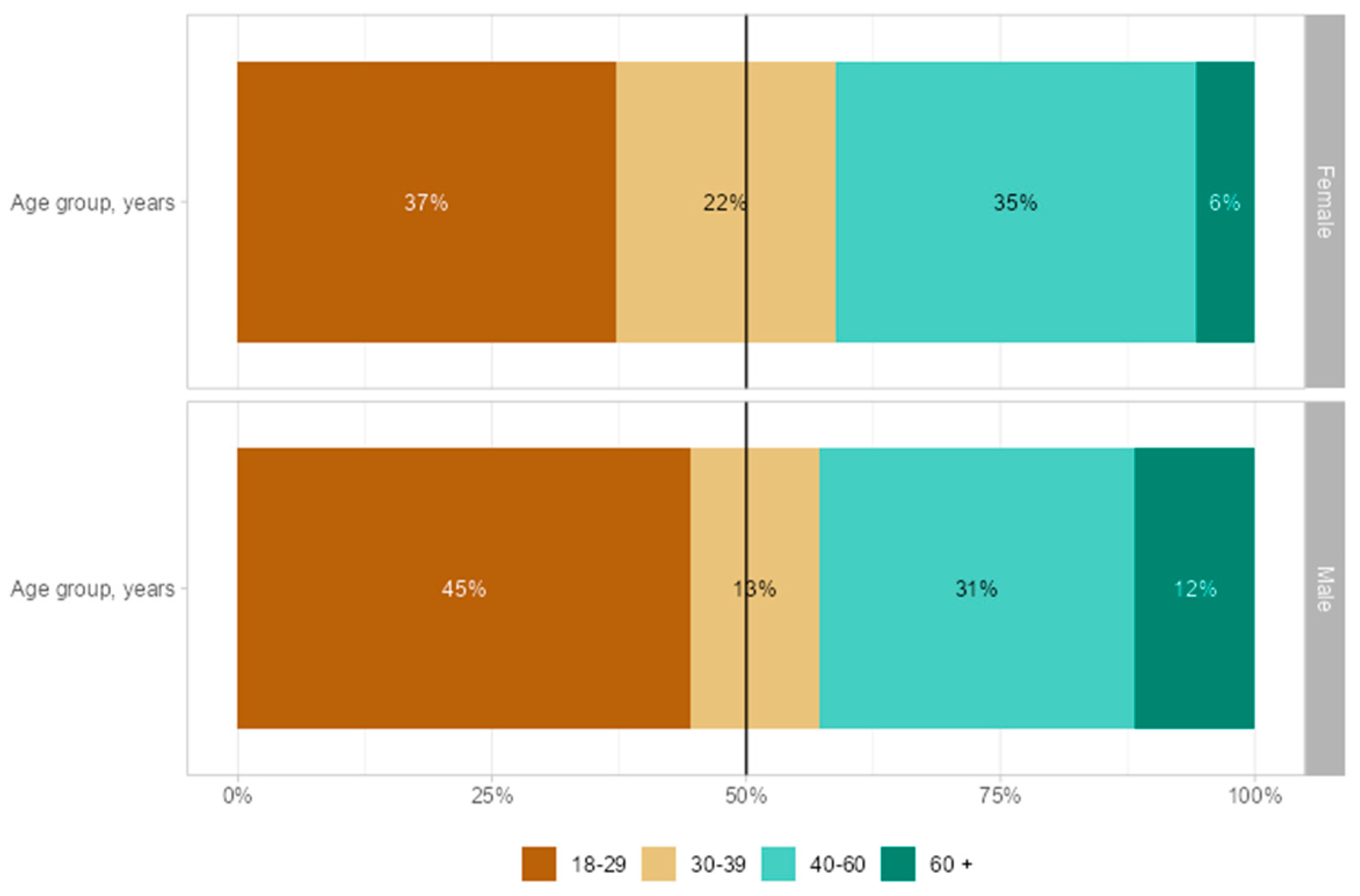

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

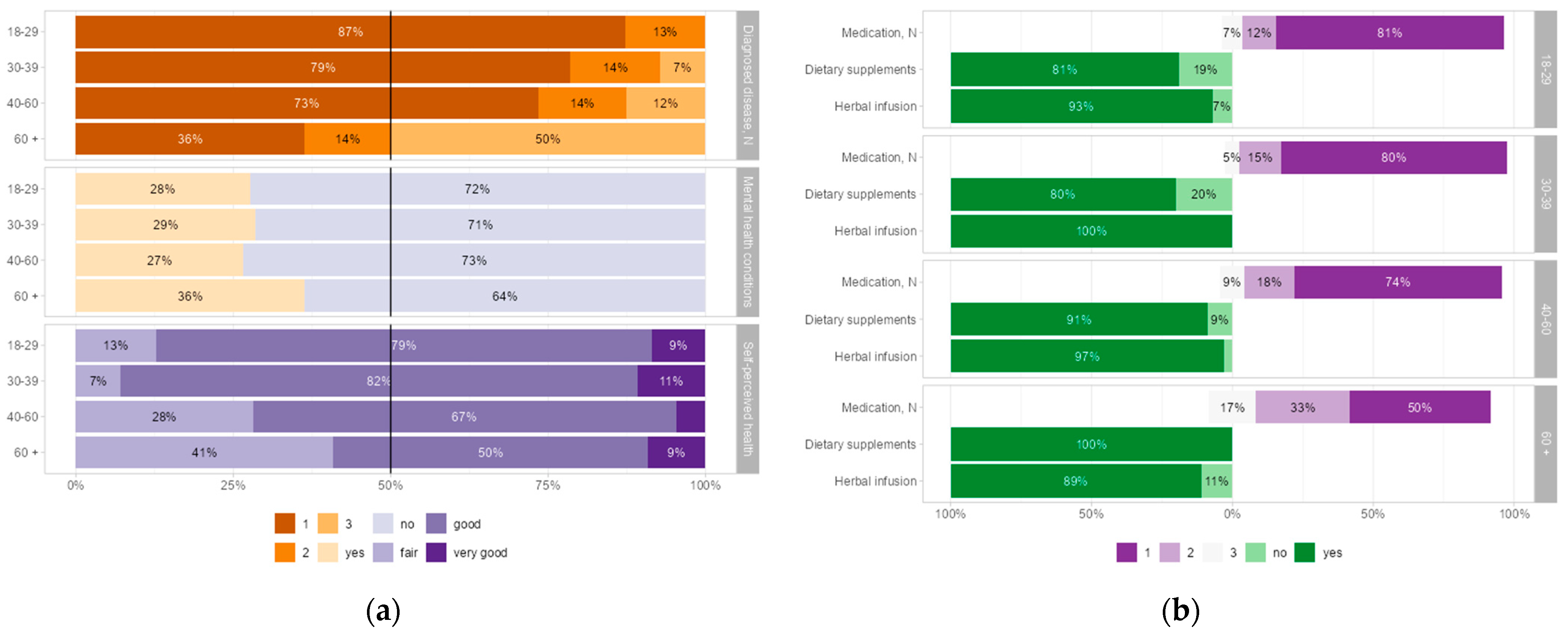

3.2. Health Status and Self-Care Practices Stratified by Sex

3.3. Health Status and Self-Care Practices Stratified by Age Group

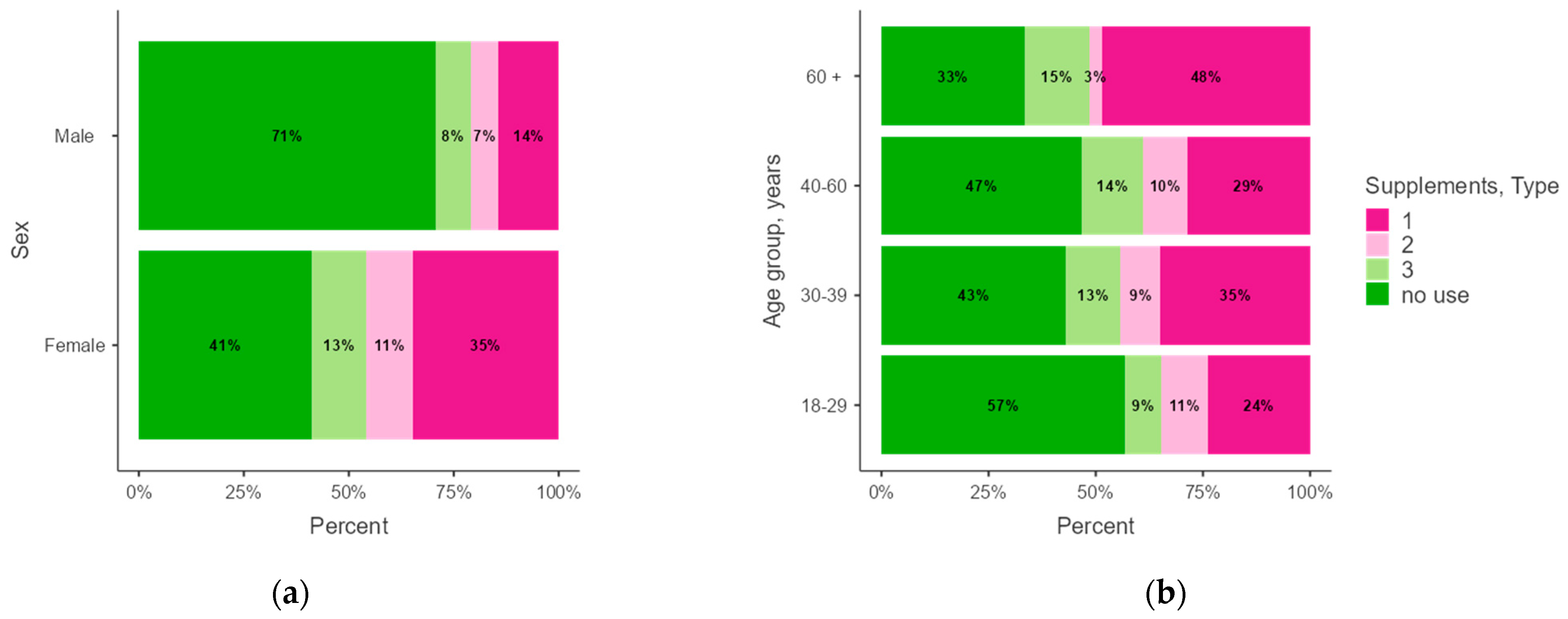

3.4. Medication and Dietary Supplement Use by Type, Sex, and Age Group

3.5. Factors Associated with Health Status and the Type of Dietary Supplements Used

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

- Accurate and informative labeling: Enforce the use of informative labels regarding ingredients and potential medication interactions.

- Adverse effects reporting: Establish a platform for reporting adverse events related to dietary supplements.

- Monitoring by healthcare professionals: Encourage professionals to monitor their patients’ use of dietary supplements.

- Prospective epidemiological and interventional studies examining dietary supplementation in older adults and individuals with multiple health conditions are encouraged;

- Studies should assess healthcare professionals’ knowledge and practices regarding dietary supplements, as well as identifying gaps and barriers in healthcare–patient communication about dietary supplementation.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CAM | Complementary and alternative medicine |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| OR | Odds ratio |

References

- Lee, E.L.; Richards, N.; Harrison, J.; Barnes, J. Prevalence of Use of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicine by the General Population: A Systematic Review of National Studies Published from 2010 to 2019. Drug Saf. 2022, 45, 713–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soukiasian, P.-D.; Kyrana, Z.; Gerothanasi, K.; Kiranas, E.; Kokokiris, L.E. Prevalence, Determinants, and Consumer Stance towards Dietary Supplements According to Sex in a Large Greek Sample: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakkar, S.; Anklam, E.; Xu, A.; Ulberth, F.; Li, J.; Li, B.; Hugas, M.; Sarma, N.; Crerar, S.; Swift, S.; et al. Regulatory Landscape of Dietary Supplements and Herbal Medicines from a Global Perspective. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2020, 114, 104647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Gahche, J.J.; Ogden, C.L.; Dimeler, M.; Potischman, N.; Ahluwalia, N. Dietary Supplement Use in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2017–March 2020; National Center for Health Statistics (U.S.): Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Directive 2002/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 10 June 2002 on the Approximation of the Laws of the Member States Relating to Food Supplements (Text with EEA Relevance). 2002, Volume 183. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2002/46/oj/eng (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Zhang, F.F.; Barr, S.I.; McNulty, H.; Li, D.; Blumberg, J.B. Health Effects of Vitamin and Mineral Supplements. BMJ 2020, 369, m2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirico, F.; Miressi, S.; Castaldo, C.; Spera, R.; Montagnani, S.; Meglio, F.D.; Nurzynska, D. Habits and Beliefs Related to Food Supplements: Results of a Survey among Italian Students of Different Education Fields and Levels. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjær, E.L.; Landet, E.R.; McNamara, C.L.; Eikemo, T.A. The Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) in Europe. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.; Sanwal, N.; Bareen, M.A.; Barua, S.; Sharma, N.; Joshua Olatunji, O.; Prakash Nirmal, N.; Sahu, J.K. Trends in Functional Beverages: Functional Ingredients, Processing Technologies, Stability, Health Benefits, and Consumer Perspective. Food Res. Int. 2023, 170, 113046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlak, C.D.R.; Drehmer, M.; Mengue, S.S. Dietary Intake of Micronutrients and Use of Vitamin and/or Mineral Supplements: Brazilian National Food Survey. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Tao, H.; Xu, J.; Liu, L.; Nahata, M.C. Quantity, Duration, Adherence, and Reasons for Dietary Supplement Use among Adults: Results from NHANES 2011–2018. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofoed, C.L.F.; Christensen, J.; Dragsted, L.O.; Tjønneland, A.; Roswall, N. Determinants of Dietary Supplement Use—Healthy Individuals Use Dietary Supplements. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, 1993–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoś, K.; Woźniak, A.; Rychlik, E.; Ziółkowska, I.; Głowala, A.; Ołtarzewski, M. Assessment of Food Supplement Consumption in Polish Population of Adults. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 733951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantor, E.D.; Rehm, C.D.; Du, M.; White, E.; Giovannucci, E.L. Trends in Dietary Supplement Use Among US Adults From 1999-2012. JAMA 2016, 316, 1464–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowe, S.; Adams, J.; Lui, C.-W.; Sibbritt, D. A Longitudinal Analysis of Self-Prescribed Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use by a Nationally Representative Sample of 19,783 Australian Women, 2006–2010. Complement. Ther. Med. 2015, 23, 699–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rautiainen, S.; Manson, J.E.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; Sesso, H.D. Dietary Supplements and Disease Prevention—A Global Overview. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2016, 12, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wierzejska, R.E. Dietary Supplements—For Whom? The Current State of Knowledge about the Health Effects of Selected Supplement Use. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petroczi, A.; Taylor, G.; Naughton, D.P. Mission Impossible? Regulatory and Enforcement Issues to Ensure Safety of Dietary Supplements. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2011, 49, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftfield, E.; O’Connell, C.P.; Abnet, C.C.; Graubard, B.I.; Liao, L.M.; Beane Freeman, L.E.; Hofmann, J.N.; Freedman, N.D.; Sinha, R. Multivitamin Use and Mortality Risk in 3 Prospective US Cohorts. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2418729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R.L.; Gahche, J.J.; Miller, P.E.; Thomas, P.R.; Dwyer, J.T. Why US Adults Use Dietary Supplements. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013, 173, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philips, C.A.; Theruvath, A.H.; Ravindran, R.; Augustine, P. Complementary and Alternative Medicines and Liver Disease. Hepatol. Commun. 2024, 8, e0417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, L.; Lambert, K. Use of Complementary and Alternative Therapies in People with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H.-H.; Lin, H.-W.; Simon Pickard, A.; Tsai, H.-Y.; Mahady, G.B. Evaluation of Documented Drug Interactions and Contraindications Associated with Herbs and Dietary Supplements: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2012, 66, 1056–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, I.; Attias, S.; Ben-Arye, E.; Goldstein, L.; Schiff, E. Adverse Events Associated with Interactions with Dietary and Herbal Supplements among Inpatients. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017, 83, 836–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babos, M.; Heinan, M.; Redmond, L.; Moiz, F.; Souza-Peres, J.; Samuels, V.; Masimukku, T.; Hamilton, D.; Khalid, M.; Herscu, P. Herb–Drug Interactions: Worlds Intersect with the Patient at the Center. Medicines 2021, 8, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bays, H.E. Safety Considerations with Omega-3 Fatty Acid Therapy. Am. J. Cardiol. 2007, 99, S35–S43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sile, I.; Teterovska, R.; Onzevs, O.; Ardava, E. Safety Concerns Related to the Simultaneous Use of Prescription or Over-the-Counter Medications and Herbal Medicinal Products: Survey Results among Latvian Citizens. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, P.M.; Martins, M.A.P.; Carvalho, M.D.G.; Castilho, R.O. Mechanisms and Interactions in Concomitant Use of Herbs and Warfarin Therapy: An Updated Review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 143, 112103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qato, D.M.; Wilder, J.; Schumm, L.P.; Gillet, V.; Alexander, G.C. Changes in Prescription and Over-the-Counter Medication and Dietary Supplement Use Among Older Adults in the United States, 2005 vs. 2011. JAMA Intern. Med. 2016, 176, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qato, D.M.; Alexander, G.C.; Conti, R.M.; Johnson, M.; Schumm, P.; Lindau, S.T. Use of Prescription and Over-the-Counter Medications and Dietary Supplements Among Older Adults in the United States. JAMA 2008, 300, 2867–2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villaescusa, L.; Zaragozá, C.; Zaragozá, F.; Tamargo, J. Herbal Medicines for the Treatment of Cardiovascular Diseases: Benefits and Risks—A Narrative Review. Int. J. Cardiol. 2023, 385, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassen, G.; Belete, G.; Carrera, K.G.; Iriowen, R.O.; Araya, H.; Alemu, T.; Solomon, N.; Bam, D.S.; Nicola, S.M.; Araya, M.E.; et al. Clinical Implications of Herbal Supplements in Conventional Medical Practice: A US Perspective. Cureus 2022, 14, e26893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frawley, J.; Adams, J.; Steel, A.; Broom, A.; Gallois, C.; Sibbritt, D. Women’s Use and Self-Prescription of Herbal Medicine during Pregnancy: An Examination of 1,835 Pregnant Women. Womens Health Issues 2015, 25, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soukiasian, P.-D.; Kyrana, Z.; Gerothanasi, K.; Kiranas, E.; Kokokiris, L.E. Fish Oil Users of Greece: Predictors, Knowledge and Habits Regarding Dietary Supplement Use. AIMS Public Health 2023, 10, 896–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simões, P.A.; Santiago, L.M.; Maurício, K.; Simões, J.A. Prevalence Of Potentially Inappropriate Medication In The Older Adult Population Within Primary Care In Portugal: A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2019, 13, 1569–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iłowiecka, K.; Maślej, M.; Czajka, M.; Pawłowski, A.; Więckowski, P.; Styk, T.; Gołkiewicz, M.; Kuzdraliński, A.; Koch, W. Lifestyle, Eating Habits, and Health Behaviors Among Dietary Supplement Users in Three European Countries. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 892233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, C.; Torres, D.; Oliveira, A.; Severo, M.; Alarcão, V.; Guiomar, S.; Mota, J.; Teixeira, P.; Rodrigues, S.; Lobato, L.; et al. Inquérito Alimentar Nacional e de Atividade Física, IAN-AF 2015–2016: Relatório de Resultados. 2017. Available online: www.ian-af.up.pt (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Kemppainen, L.M.; Kemppainen, T.T.; Reippainen, J.A.; Salmenniemi, S.T.; Vuolanto, P.H. Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine in Europe: Health-Related and Sociodemographic Determinants. Scand. J. Public Health 2018, 46, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portela, F.; Dias, C.C.; Caldeira, P.; Cravo, M.; Deus, J.; Gonçalves, R.; Lago, P.; Morna, H.; Peixe, P.; Ramos, J.; et al. The Who-When-Why Triangle of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use among Portuguese IBD Patients. Dig. Liver Dis. 2017, 49, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, M.J.; Garbacz, A.; Czlapka-Klapinska, N.; Czlapka-Matyasik, M.; Pena, A. Key Factors Driving Portuguese Individuals to Use Food Supplements—Findings from a Cross-Sectional Study. Foods 2025, 14, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, A.C.; Pádua, I.; Gonçalves, V.M.F.; Ribeiro, C.; Leal, S. Exploring Tea and Herbal Infusions Consumption Patterns and Behaviours: The Case of Portuguese Consumers. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavaddat, N.; Valderas, J.M.; van der Linde, R.; Khaw, K.T.; Kinmonth, A.L. Association of Self-Rated Health with Multimorbidity, Chronic Disease and Psychosocial Factors in a Large Middle-Aged and Older Cohort from General Practice: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Fam. Pract. 2014, 15, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaaban, A.N.; Martins, M.R.O.; Peleteiro, B. Factors Associated with Self-Perceived Health Status in Portugal: Results from the National Health Survey 2014. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 879432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautiainen, S.; Wang, L.; Gaziano, J.M.; Sesso, H.D. Who Uses Multivitamins? A Cross-Sectional Study in the Physicians’ Health Study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2014, 53, 1065–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snyder, C.F.; Watson, M.E.; Jackson, J.D.; Cella, D.; Halyard, M.Y.; Mayo/FDA Patient-Reported Outcomes Consensus Meeting Group. Patient-Reported Outcome Instrument Selection: Designing a Measurement Strategy. Value Health 2007, 10, S76–S85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heymsfield, S.B.; Sorkin, J.D.; Thomas, D.M.; Yang, S.; Heo, M.; McCarthy, C.; Brown, J.; Pietrobelli, A. Weight/Height2: Mathematical Overview of the World’s Most Widely Used Adiposity Index. Obes. Rev. 2025, 26, e13842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pursey, K.; Burrows, T.L.; Stanwell, P.; Collins, C.E. How Accurate Is Web-Based Self-Reported Height, Weight, and Body Mass Index in Young Adults? J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Physical Status: The Use of and Interpretation of Anthropometry, Report of a WHO Expert Committee; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1995; ISBN 978-92-4-120854-3. [Google Scholar]

- Mohd Ashri, M.H.; Abu Saad, H.; Adznam, S.N.Ά. Socio-Demographic Characteristics, Body Weight Status and Energy Intake among Users and Non-Users of Dietary Supplements among Government Employees in Putrajaya, Malaysia. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, S.C.; Holroyd-Leduc, J.M.; Poulin, M.J.; Hogan, D.B. Effect of Nutrients, Dietary Supplements and Vitamins on Cognition: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Can. Geriatr. J. 2015, 18, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, Y.; Omura, T.; Toyoshima, K.; Araki, A. Nutrition Management in Older Adults with Diabetes: A Review on the Importance of Shifting Prevention Strategies from Metabolic Syndrome to Frailty. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutor, A.; O’Keefe, E.L.; Lavie, C.J.; Elagizi, A.; Milani, R.; O’Keefe, J. Omega-3 Fatty Acids in Primary and Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular Diseases. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2024, 84, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, S.J.; Lincoff, A.M.; Garcia, M.; Bash, D.; Ballantyne, C.M.; Barter, P.J.; Davidson, M.H.; Kastelein, J.J.P.; Koenig, W.; McGuire, D.K.; et al. Effect of High-Dose Omega-3 Fatty Acids vs Corn Oil on Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Patients at High Cardiovascular Risk: The STRENGTH Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2020, 324, 2268–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumà-Lao, J.; Arpino, B. A Machine Learning Approach to Determine the Influence of Specific Health Conditions on Self-Rated Health across Education Groups. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caramenti, M.; Castiglioni, I. Determinants of Self-Perceived Health: The Importance of Physical Well-Being but Also of Mental Health and Cognitive Functioning. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crimmins, E.M.; Kim, J.K.; Solé-Auró, A. Gender Differences in Health: Results from SHARE, ELSA and HRS. Eur. J. Public Health 2011, 21, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumà, J. What Influences Individual Perception of Health? Using Machine Learning to Disentangle Self-Perceived Health. SSM Popul. Health 2021, 16, 100996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laffin, L.J.; Bruemmer, D.; Garcia, M.; Brennan, D.M.; McErlean, E.; Jacoby, D.S.; Michos, E.D.; Ridker, P.M.; Wang, T.Y.; Watson, K.E.; et al. Comparative Effects of Low-Dose Rosuvastatin, Placebo, and Dietary Supplements on Lipids and Inflammatory Biomarkers. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 81, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gohar, F.; Greenfield, S.M.; Beevers, D.G.; Lip, G.Y.; Jolly, K. Self-Care and Adherence to Medication: A Survey in the Hypertension Outpatient Clinic. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2008, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, A.J.; Santomauro, D.F.; Aali, A.; Abate, Y.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd ElHafeez, S.; Abdelmasseh, M.; Abd-Elsalam, S.; Abdollahi, A.; et al. Global Incidence, Prevalence, Years Lived with Disability (YLDs), Disability-Adjusted Life-Years (DALYs), and Healthy Life Expectancy (HALE) for 371 Diseases and Injuries in 204 Countries and Territories and 811 Subnational Locations, 1990–2021: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 403, 2133–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halli-Tierney, A.D.; Scarbrough, C.; Carroll, D. Polypharmacy: Evaluating Risks and Deprescribing. Am. Fam. Physician 2019, 100, 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Tamargo, J.; Kjeldsen, K.P.; Delpón, E.; Semb, A.G.; Cerbai, E.; Dobrev, D.; Savarese, G.; Sulzgruber, P.; Rosano, G.; Borghi, C.; et al. Facing the Challenge of Polypharmacy When Prescribing for Older People with Cardiovascular Disease. A Review by the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy. Eur. Heart J.—Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 2022, 8, 406–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krska, J.; Corlett, S.A.; Katusiime, B. Complexity of Medicine Regimens and Patient Perception of Medicine Burden. Pharmacy 2019, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, C.; Zang, E.; Shi, R.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, K.; Li, M. Review on Herbal Tea as a Functional Food: Classification, Active Compounds, Biological Activity, and Industrial Status. J. Future Foods 2023, 3, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, P.; Buettner, C.; Davis, R.B.; Phillips, R.S.; Kemper, K.J. Factors and Common Conditions Associated with Adolescent Dietary Supplement Use: An Analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2008, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messerer, M.; Wolk, A. Sensitivity and Specificity of Self-Reported Use of Dietary Supplements. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 58, 1669–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

| Participants | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | |||||

| Characteristics | Total N = 449 | Female 330 (73) | Male 119 (27) | p Value | Cramér’s V |

| Diagnosed disease | 0.017 | 0.11 | |||

| No | 288 (64) | 201 (61) | 87 (73) | ||

| Yes | 161 (36) | 129 (39) | 32 (27) | ||

| Diagnosed disease, N | 0.018 | 0.22 | |||

| 1 disease | 118 (73) | 99 (77) | 19 (59) | ||

| 2 diseases | 22 (14) | 18 (14) | 4 (13 | ||

| ≥3 diseases | 21 (13) | 12 (9) | 9 (28) | ||

| Mental health conditions | 0.62 | -- | |||

| No | 115 (71) | 91 (71) | 24 (75) | ||

| Yes | 46 (29) | 38 (29) | 8 (25) | ||

| BMI categories | <0.001 | 0.22 | |||

| Normal weight | 284 (63) | 229 (70) | 55 (46) | ||

| Overweight | 110 (25) | 65 (20) | 45 (38) | ||

| Obese | 44 (10) | 27 (8) | 17 (14) | ||

| Underweight | 10 (2) | 8 (2) | 2 (2) | ||

| Self-perceived health | 0.91 | -- | |||

| Good | 310 (69) | 228 (69) | 82 (69) | ||

| Very good | 83 (18) | 62 (19) | 21 (18) | ||

| Fair | 56 (12) | 40 (12) | 16 (13) | ||

| Medication use | <0.001 | 0.19 | |||

| No | 335 (75) | 230 (70) | 105 (88) | ||

| Yes | 114 (25) | 100 (30) | 14 (12) | ||

| Medication, N | 0.45 | -- | |||

| 1 medication | 84 (74) | 73 (73) | 11 (79) | ||

| 2 medications | 20 (18) | 19 (19) | 1 (7) | ||

| ≥3 medications | 10 (9) | 8 (8) | 2 (14) | ||

| Dietary supplement use | <0.001 | 0.26 | |||

| No | 220 (49) | 136 (41) | 84 (71) | ||

| Yes | 229 (51) | 194 (59) | 35 (29) | ||

| Dietary supplement type | <0.001 | 0.26 | |||

| (1) Multivitamin–mineral supplements | 132 (29) | 115 (35) | 17 (14) | ||

| (2) Other supplements | 44 (10) | 36 (11) | 8 (7) | ||

| (3) Both types of supplements | 53 (12) | 43 (13) | 10 (8) | ||

| Multivitamin–Mineral Supplement | Both Supplement Types | No Use | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |

| OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male (vs. Female) | 0.67 (0.27–1.67) | 0.65 (0.25–1.70) | 1.05 (0.37–2.93) | 1.00 (0.35–2.87) | 2.78 (1.23–6.27) | 2.14 (0.92–4.96) |

| Age Groups, Years | ||||||

| 30–39 (vs. 18–29) | 1.70 (0.66–4.38) | 1.81 (0.69–4.76) | 1.74 (0.56–5.42) | 1.82 (0.58–5.69) | 0.88 (0.35–2.18) | 0.91 (0.36–2.33) |

| 40–60 (vs. 18–29) | 1.24 (0.57–2.74) | 1.40 (0.62–3.14) | 1.74 (0.68–4.43) | 1.87 (0.72–4.82) | 0.85 (0.41–1.78) | 0.94 (0.44–2.02) |

| 60+ (vs. 18–29) | 7.24 (0.89–58.63) | 7.15 (0.85–60.30) | 6.33 (0.67–60.17) | 6.33 (0.64–62.64) | 2.09 (0.25–17.16) | 3.21 (0.36–28.46) |

| Diagnosed Diseases | ||||||

| Yes (vs. No) | 1.03 (0.52–2.04) | 0.70 (0.34–1.47) | 0.96 (0.43–2.14) | 0.75 (0.32–1.76) | 0.26 (0.13–0.52) | 0.34 (0.17–0.69) |

| Medication Use | ||||||

| Yes (vs. No) | 2.38 (1.15–4.96) | 2.35 (1.08–5.12) | 1.45 (0.62–3.39) | 1.50 (0.60–3.72) | 0.17 (0.08–0.40) | 0.25 (0.10–0.60) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leal, S.; Sousa, A.C.; Valdiviesso, R.; Pádua, I.; Gonçalves, V.M.F.; Ribeiro, C. Exploring Factors Associated with Health Status and Dietary Supplement Use Among Portuguese Adults: A Cross-Sectional Online Survey. Healthcare 2025, 13, 769. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070769

Leal S, Sousa AC, Valdiviesso R, Pádua I, Gonçalves VMF, Ribeiro C. Exploring Factors Associated with Health Status and Dietary Supplement Use Among Portuguese Adults: A Cross-Sectional Online Survey. Healthcare. 2025; 13(7):769. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070769

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeal, Sandra, Ana Catarina Sousa, Rui Valdiviesso, Inês Pádua, Virgínia M. F. Gonçalves, and Cláudia Ribeiro. 2025. "Exploring Factors Associated with Health Status and Dietary Supplement Use Among Portuguese Adults: A Cross-Sectional Online Survey" Healthcare 13, no. 7: 769. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070769

APA StyleLeal, S., Sousa, A. C., Valdiviesso, R., Pádua, I., Gonçalves, V. M. F., & Ribeiro, C. (2025). Exploring Factors Associated with Health Status and Dietary Supplement Use Among Portuguese Adults: A Cross-Sectional Online Survey. Healthcare, 13(7), 769. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070769