Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms Following Childbirth: A Contribution to the Psychometric Evaluation of the Greek Version of the Traumatic Event Scale (TES) (Version B)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Traumatic Event Scale Version B (TES-B)—Translation Stage

2.2. Traumatic Event Scale Version B (TES-B)—Pilot Testing Stage

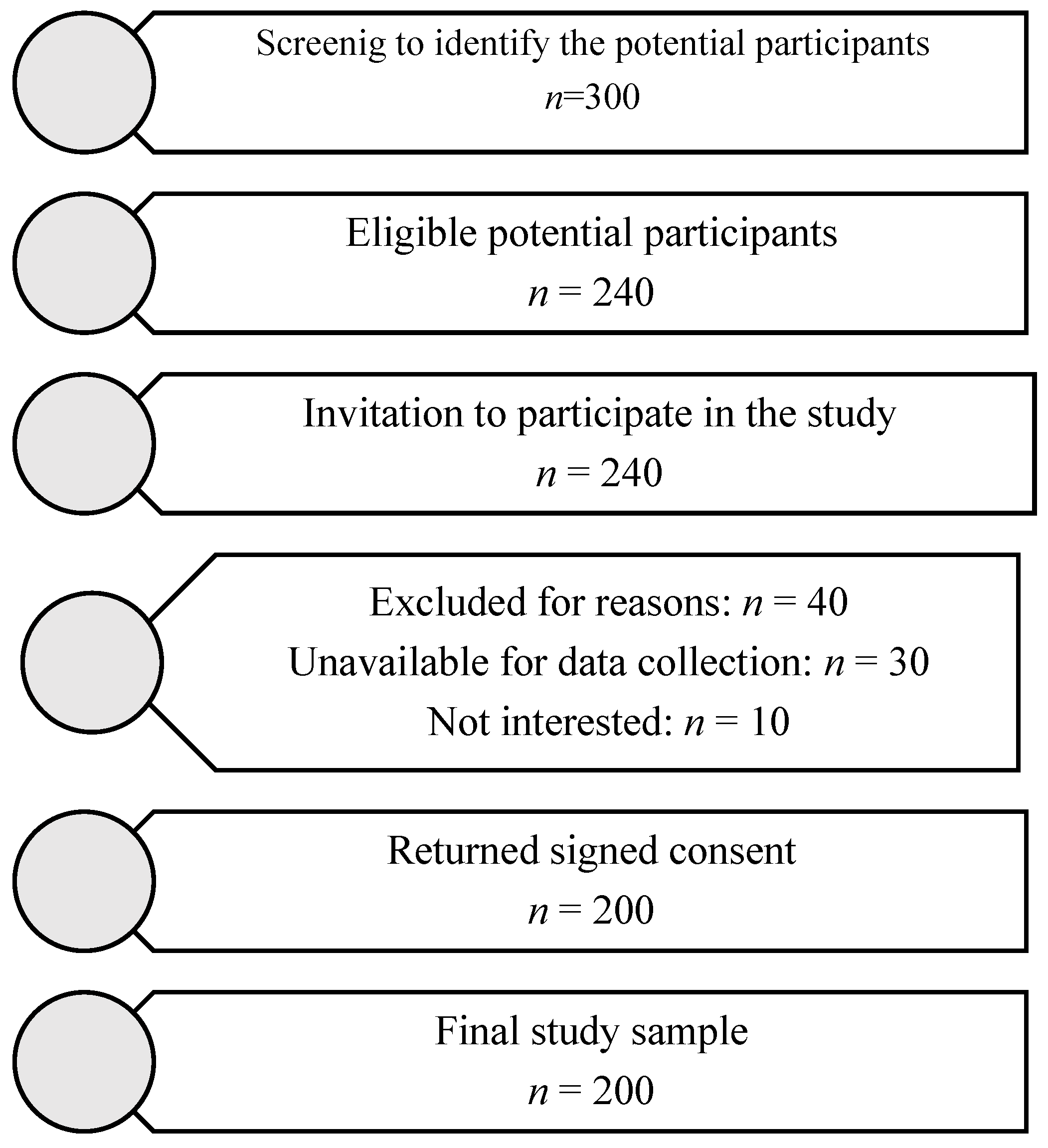

2.3. Study Sample

2.4. Study Procedure

2.5. Measures

2.5.1. Traumatic Event Scale Version B (TES-B)

2.5.2. Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS)

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.3. Descriptive Statistics on the Distribution of Responses and the Mean Scores on the GrTES-B and the Internal Consistency of the GrTES-B

3.4. Convergent and Divergent Validity

3.5. Correlation Coefficients Between the GrTES-A and the GrTES-B

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CFA | Confirmatory factor analysis |

| CFI | Comparative fit index |

| DSM | Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders |

| EPDS | Edinburgh postpartum depression scale |

| ETISR-SF | Early Trauma Inventory-Self Report-Short Form |

| GrTES | Greek version of the TES |

| IES-R | Impact of Event Scale—Revised |

| PCL-5 | Posttraumatic Check List-5 |

| PCL-C | PTSD Checklist—civilian scale |

| PTSD | Post-traumatic stress disorder |

| PTS | Post-traumatic stress |

| r | Spearman’s correlation coefficient |

| RMSEA | Root mean square error of approximation |

| TES | Traumatic event scale |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewis index |

References

- Zaers, S.; Waschke, M.; Ehlert, U. Depressive symptoms and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder in women after childbirth. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2008, 29, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, L.M.; Molyneaux, E.; Dennis, C.L.; Rochat, T.; Stein, A.; Milgrom, J. Non-psychotic mental disorders in the perinatal period. Lancet 2014, 384, 1775–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, M.H.; Furuta, M.; Small, R.; McKenzie-McHarg, K.; Bick, D. Debriefing interventions for the prevention of psychological trauma in women following childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 10, CD007194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, T.M.; Marshall, A.D.; Taft, C.T. Posttraumatic stress disorder: Etiology, epidemiology, and treatment outcome. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 2, 161–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; pp. 271–280. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, X.R.; Chen, Q.B.; Wei, K.; Tao, K.M.; Lu, Z.J. Posttraumatic stress disorder: From diagnosis to prevention. Mil. Med. Res. 2018, 5, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinhoven, P.; Penninx, B.W.; van Hemert, A.M.; de Rooij, M.; Elzinga, B.M. Comorbidity of PTSD in anxiety and depressive disorders: Prevalence and shared risk factors. Child Abuse Negl. 2014, 38, 1320–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, J.; Diao, H.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, C.; Chen, Y.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Y. Post-traumatic stress disorder: A psychiatric disorder requiring urgent attention. Med. Rev. 2022, 2, 219–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, R.A.; Creamer, M.; O’Donnell, M.; Forbes, D.; McFarlane, A.C.; Silove, D.; Hadzi-Pavlovic, D. Acute and chronic posttraumatic stress symptoms in the emergence of posttraumatic stress disorder: A network analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, R.A. Post-traumatic stress disorder: A state-of-the-art review of evidence and challenges. World Psychiatry 2019, 18, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsella, A.J. Ethnocultural aspects of PTSD: An overview of concepts, issues, and treatments. Traumatology 2010, 16, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J.; Zaretsky, A. Assessment and Management of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Continuum 2018, 24, 873–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaton, D.E.; Bombardier, C.; Guillemin, F.; Ferraz, M.B. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine 2000, 25, 3186–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolaitis, G.; Olff, M. Psychotraumatology in Greece. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2017, 8, 135175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannopoulou, I.; Strouthos, M.; Smith, P.; Dikaiakou, A.; Galanopoulou, V.; Yule, W. Post-traumatic stress reactions of children and adolescents exposed to the Athens 1999 earthquake. Eur. Psychiatry 2006, 21, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonopoulou, Z.; Konstantakopoulos, G.; Τzinieri-Coccosis, M.; Sinodinou, C. Rates of childhood trauma in a sample of university students in Greece: The Greek version of the Early Trauma Inventory-Self Report. Psychiatrike 2017, 28, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Andreou, E.; Tsermentseli, S.; Anastasiou, O.; Kouklari, E.C. Retrospective Accounts of Bullying Victimization at School: Associations with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms and Post-Traumatic Growth among University Students. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2020, 14, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafoori, B.; Triliva, S.; Chrysikopoulou, P.; Vavvos, A. Resilience, Coping Self-Efficacy, and Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms among Healthcare Workers Who Work with Refugees and Asylum Seekers in Greece. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalaitzaki, A. Posttraumatic symptoms, posttraumatic growth, and internal resources among the general population in Greece: A nation-wide survey amid the first COVID-19 lockdown. Int. J. Psychol. 2021, 56, 766–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappa, S.; Barmparessou, Z.; Athanasiou, N.; Sakka, E.; Eleftheriou, K.; Patrinos, S.; Sakkas, N.; Pappas, A.; Kalomenidis, I.; Katsaounou, P. Depression, Insomnia and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in COVID-19 Survivors: Role of Gender and Impact on Quality of Life. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilias, I.; Mantziou, V.; Vamvakas, E.; Kampisiouli, E.; Theodorakopoulou, M.; Vrettou, C.; Douka, E.; Vassiliou, A.G.; Orfanos, S.; Kotanidou, A.; et al. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Burnout in Healthcare Professionals During the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 7, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinweber, J.; Fontein-Kuipers, Y.; Thomson, G.; Karlsdottir, S.I.; Nilsson, C.; Ekström-Bergström, A.; Olza, I.; Hadjigeorgiou, E.; Stramrood, C. Developing a woman-centered, inclusive definition of traumatic childbirth experiences: A discussion paper. Birth 2022, 49, 687–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olde, E.; van der Hart, O.; Kleber, R.; van Son, M. Posttraumatic stress following childbirth: A review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 26, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halvorsen, L.; Nerum, H.; Oian, P.; Sørlie, T. Giving birth with rape in one’s past: A qualitative study. Birth 2013, 40, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bydlowski, M.; Raoul-Duval, A. Un avatar psychique meconnu de la puerpralite: La nervosa traumatique post obstetricale. Perspect. Psychiatr. 1978, 4, 321–328. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, C.T. Birth trauma: In the eye of the beholder. Nurs. Res. 2004, 53, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soet, J.E.; Brack, G.A.; DiIorio, C. Prevalence and predictors of women’s experience of psychological trauma during childbirth. Birth 2003, 30, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcorn, K.L.; O’Donovan, A.; Patrick, J.C.; Creedy, D.; Devilly, G.J. A prospective longitudinal study of the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder resulting from childbirth events. Psychol. Med. 2010, 40, 1849–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stramrood, C.A.; Paarlberg, K.M.; Huis In ’t Veld, E.M.; Berger, L.W.; Vingerhoets, A.J.; Schultz, W.C.; van Pampus, M.G. Posttraumatic stress following childbirth in homelike- and hospital settings. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2011, 32, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boorman, R.J.; Devilly, G.J.; Gamble, J.; Creedy, D.K.; Fenwick, J. Childbirth and criteria for traumatic events. Midwifery 2014, 30, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekel, S.; Stuebe, C.; Dishy, G. Childbirth Induced Posttraumatic Stress Syndrome: A Systematic Review of Prevalence and Risk Factors. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkmen, H.; Yalniz Dilcen, H.; Akin, B. The Effect of Labor Comfort on Traumatic Childbirth Perception, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, and Breastfeeding. Breastfeed. Med. 2020, 15, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommerlad, S.; Schermelleh-Engel, K.; La Rosa, V.L.; Louwen, F.; Oddo-Sommerfeld, S. Trait anxiety and unplanned delivery mode enhance the risk for childbirth-related post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in women with and without risk of preterm birth: A multi sample path analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyne, C.S.; Kazmierczak, M.; Souday, R.; Horesh, D.; Lambregtse-van den Berg, M.; Weigl, T.; Horsch, A.; Oosterman, M.; Dikmen-Yildiz, P.; Garthus-Niegel, S. Prevalence and risk factors of birth-related posttraumatic stress among parents: A comparative systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 94, 102157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, P.D.; Ayers, S.; Phillips, L. The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in pregnancy and after birth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 208, 634–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekel, S.; Ein-Dor, T.; Berman, Z.; Barsoumian, I.S.; Agarwal, S.; Pitman, R.K. Delivery mode is associated with maternal mental health following childbirth. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2019, 22, 817–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiel, F.; Dekel, S. Peritraumatic dissociation in childbirth-evoked posttraumatic stress and postpartum mental health. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2020, 23, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grekin, R.; O’Hara, M.W. Prevalence and risk factors of postpartum posttraumatic stress disorder: A meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2014, 34, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, L.B.; Melvaer, L.B.; Videbech, P.; Lamont, R.F.; Joergensen, J.S. Risk factors for developing post-traumatic stress disorder following childbirth: A systematic review. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2012, 91, 1261–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson-Hollands, J.; Jun, J.J.; Sloan, D.M. The association between peritraumatic dissociation and PTSD symptoms: The mediating role of negative beliefs about the self. J. Trauma. Stress 2017, 30, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, S. Women’s experiences of symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after traumatic childbirth: A review and critical appraisal. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2015, 18, 761–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, F.; Ein-Dor, T.; Dishy, G.; King, A.; Dekel, S. Examining symptom clusters of childbirth-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2018, 20, 18m02322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Sieleghem, S.; Danckaerts, M.; Rieken, R.; Okkerse, J.M.E.; de Jonge, E.; Bramer, W.M.; Lambregtse-van den Berg, M.P. Childbirth related PTSD and its association with infant outcome: A systematic review. Early Hum. Dev. 2022, 174, 105667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garthus-Niegel, S.; Horsch, A.; Ayers, S.; Junge-Hoffmeister, J.; Weidner, K.; Eberhard-Gran, M. The influence of postpartum PTSD on breastfeeding: A longitudinal population-based study. Birth 2018, 45, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dekel, S.; Thiel, F.; Dishy, G.; Ashenfarb, A.L. Is childbirth-induced PTSD associated with low maternal attachment? Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2019, 22, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayopoulos, G.A.; Ein-Dor, T.; Dishy, G.A.; Nandru, R.; Chan, S.J.; Hanley, L.E.; Kaimal, A.J.; Dekel, S. COVID-19 is associated with traumatic childbirth and subsequent mother-infant bonding problems. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 282, 122–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garthus-Niegel, S.; Horsch, A.; Bickle Graz, M.; Martini, J.; von Soest, T.; Weidner, K.; Eberhard-Gran, M. The prospective relationship between postpartum PTSD and child sleep: A 2-year follow-up study. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 241, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollander, M.; de Miranda, E.; van Dillen, J.; de Graaf, I.; Vandenbussche, F.; Holten, L. Women’s motivations for choosing a high risk birth setting against medical advice in the Netherlands: A qualitative analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottvall, K.; Waldenström, U. Does a traumatic birth experience have an impact on future reproduction? BJOG 2002, 109, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delicate, A.; Ayers, S.; McMullen, S. Health care practitioners’ views of the support women, partners, and the couple relationship require for birth trauma: Current practice and potential improvements. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2020, 21, e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delicate, A.; Ayers, S.; McMullen, S. Health-care practitioners’ assessment and observations of birth trauma in mothers and partners. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2022, 40, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermetten, E.; Zhohar, J.; Krugers, H.J. Pharmacotherapy in the aftermath of trauma; opportunities in the ‘golden hours’. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2014, 16, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmi, L.; Fostick, L.; Burshtein, S.; Cwikel-Hamzany, S.; Zohar, J. PTSD treatment in light of DSM-5 and the “golden hours” concept. CNS Spectr. 2016, 21, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Gevonden, M.; Shalev, A. Prevention of post-traumatic stress disorder after trauma: Current evidence and future directions. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2016, 18, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice. Screening for Perinatal Depression. Committee Opinion Number 757, November 2018. Available online: https://www.acog.org/programs/perinatal-mental-health/implementing-perinatal-mental-health-screening (accessed on 20 November 2018).

- Bremner, J.D.; Bolus, R.; Mayer, E.A. Psychometric properties of the early trauma inventory-self report. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2007, 195, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weathers, F.W.; Litz, B.T.; Keane, T.M.; Palmieri, P.A.; Marx, B.P.; Schnurr, P.P. The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). 2014. Available online: http://www.ptsd.va.gov (accessed on 2 February 2020).

- Hyer, K.; Brown, L.M. The Impact of Event Scale-Revised: A quick measure of a patient’s response to trauma. Am. J. Nurs. 2008, 108, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mystakidou, K.; Tsilika, E.; Parpa, E.; Galanos, A.; Vlahos, L. Psychometric properties of the Impact of Event Scale in Greek cancer patients. J. Pain Symptom. Manag. 2007, 33, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weathers, F.W.; Litz, B.T.; Herman, D.; Huska, J.; Keane, T. The PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version (PCL-C); National Center for PTSD: Boston, MA, USA, 1994.

- Calbari, E.; Anagnostopoulos, F. Exploratory factor analysis of the Greek adaptation of the PTSD checklist—Civilian version. J. Loss Trauma 2010, 15, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijma, K.; Söderquist, J.; Wijma, B. Posttraumatic stress disorder after childbirth: A cross sectional study. J. Anxiety Disord. 1997, 11, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderquist, J.; Wijma, K.; Wijma, B. Traumatic stress after childbirth: The role of obstetric variables. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2002, 23, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderquist, J.; Wijma, B.; Wijma, K. The longitudinal course of post-traumatic stress after childbirth. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2006, 27, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderquist, J.; Wijma, B.; Thorbert, G.; Wijma, K. Risk factors in pregnancy for post-traumatic stress and depression after childbirth. BJOG 2009, 116, 672–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, P.; Zervas, I.; Lykeridou, A.; Deltsidou, A. Traumatic event scale: A pilot study in Greece. Int. J. Caring Sci. 2022, 15, 143. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, J.L.; Holden, J.M.; Sagovsky, R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br. J. Psychiatry 1987, 150, 782–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonardou, A.A.; Zervas, Y.M.; Papageorgiou, C.C.; Marks, M.N.; Tsartsara, E.C.; Antsaklis, A.; Christodoulou, G.N.; Soldatos, C.R. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale and prevalence of postnatal depression at two months postpartum in a sample of Greek mothers. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2009, 27, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béland, M.; Chabot, K.; Goulet Gervais, L.; Morin, A.J.; Gosselin, P. Évaluation de la peur de l’accouchement. Validation et adaptation française d’une échelle mesurant la peur de l’accouchement [French adaptation and validation of a scale measuring the fear of childbirth]. Encephale 2012, 38, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varela, P.; Lykeridou, A.; Zervas, I.; Deltsidou, A. Psychometric properties of the Greek Version of the Traumatic Event Scale (TES) (Version A) among low-risk pregnant women. BMC Psychol. 2023, 11, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, R. Basic Principles of Structural Equation Modeling: An Introduction to LISREL and EQS; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 62–127. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M. On the fit of models to covariances and methodology to the Bulletin. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 400–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenspoon, P.J.; Saklofske, D.H. Confirmatory factor analysis of the multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale. Pers. Individ. Differ. 1998, 25, 965–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.; Bernstein, R. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill Companies, Incorporated: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Stramrood, C.; Slade, P. A woman afraid of becoming pregnant again: Posttraumatic stress disorder following childbirth. In Bio-Psycho-Social Obstetrics and Gynecology: A Competency-Oriented Approach; Springer International Publishing/Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranenburg, L.; Lambregtse-van den Berg, M.; Stramrood, C. Traumatic Childbirth Experience and Childbirth-Related Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): A Contemporary Overview. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anokye, R.; Acheampong, E.; Budu-Ainooson, A.; Obeng, E.I.; Akwasi, A.G. Prevalence of postpartum depression and interventions utilized for its management. Ann. Gen. Psych. 2018, 17, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lackie, M.E.; Parrilla, J.S.; Lavery, B.M.; Kennedy, A.L.; Ryan, D.; Shulman, B.; Brotto, L.A. Digital Health Needs of Women With Postpartum Depression: Focus Group Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e18934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A. Postpartum help-seeking: The role of stigma and mental health literacy. Matern. Child Health J. 2022, 26, 1030–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attanasio, L.B.; Ranchoff, B.L.; Cooper, M.I.; Geissler, K.H. Postpartum visit attendance in the United States: A Systematic Review. Womens Health Issues 2022, 32, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, P.; Murphy, A.; Hayden, E. Identifying post-traumatic stress disorder after childbirth. BMJ 2022, 377, e067659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuta, M.; Horsch, A.; Ng, E.S.W.; Bick, D.; Spain, D.; Sin, J. Effectiveness of Trauma-Focused Psychological Therapies for Treating Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms in Women Following Childbirth: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slade, P.P.; Molyneux, D.R.; Watt, D.A. A systematic review of clinical effectiveness of psychological interventions to reduce post-traumatic stress symptoms following childbirth and a meta-synthesis of facilitators and barriers to uptake of psychological care. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 281, 678–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekel, S.; Papadakis, J.E.; Quagliarini, B.; Jagodnik, K.M.; Nandru, R. A Systematic Review of Interventions for Prevention and Treatment of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Following Childbirth. medRxiv 2023, 23294230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.J.; Ein-Dor, T.; Mayopoulos, P.A.; Mesa, M.M.; Sunda, R.M.; McCarthy, B.F.; Kaimal, A.J.; Dekel, S. Risk factors for developing posttraumatic stress disorder following childbirth. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 290, 113090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Nationality | |

| Greek | 192 (96.0) |

| Other | 8 (4) |

| Married/Living with partner | 199 (99.5) |

| Occupation | |

| Employed | 158 (79) |

| Unemployed | 28 (14.0) |

| Household | 14 (7.0) |

| Visited a specialist for psychological problems in the past | 65 (32.5) |

| Psychotherapy in the past | 45 (22.5) |

| Being abused during childhood | 49 (24.5) |

| Being abused during adulthood | 49 (24.5) |

| Stressful event during last year | 82 (41.0) |

| Primigravida | 104 (52.0) |

| Vaginal delivery | 159 (80) |

| Caesarean section | 40 (20.0) |

| Description of current childbirth experience | |

| Very positive | 66 (33.0) |

| Mainly positive | 107 (53.5) |

| Very negative | 11 (5.5) |

| Mainly negative | 16 (8.0) |

| GrTES-Β | Never/Not at All | Rarely | Sometimes | Often |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Ν (%) | Ν (%) | Ν (%) | Ν (%) |

| a | 10 (5.2) | 62 (32.5) | 69 (36.1) | 50 (26.2) |

| b | 91 (47.6) | 74 (38.7) | 19 (9.9) | 7 (3.7) |

| c | 122 (63.5) | 49 (25.5) | 14 (7.3) | 7 (3.6) |

| d | 76 (39.6) | 76 (39.6) | 25 (13) | 15 (7.8) |

| 1 | 144 (72) | 32 (16) | 19 (9.5) | 5 (2.5) |

| 2 | 195 (97.5) | 5 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 3 | 189 (94.5) | 7 (3.5) | 4 (2) | 0 (0) |

| 4 | 149 (74.5) | 29 (14.5) | 17 (8.5) | 5 (2.5) |

| 5 | 172 (86) | 21 (10.5) | 6 (3) | 1 (0.5) |

| 6 | 163 (81.5) | 25 (12.5) | 5 (2.5) | 7 (3.5) |

| 7 | 168 (84) | 22 (11) | 7 (3.5) | 3 (1.5) |

| 8 | 125 (62.5) | 49 (24.5) | 25 (12.5) | 1 (0.5) |

| 9 | 127 (63.5) | 38 (19) | 28 (14) | 7 (3.5) |

| 10 | 141 (70.5) | 24 (12) | 29 (14.5) | 6 (3) |

| 11 | 170 (85) | 22 (11) | 7 (3.5) | 1 (0.5) |

| 12 | 181 (90.5) | 14 (7) | 5 (2.5) | 0 (0) |

| 13 | 181 (90.5) | 14 (7) | 5 (2.5) | 0 (0) |

| 14 | 98 (49) | 59 (29.5) | 34 (17) | 9 (4.5) |

| 15 | 90 (45) | 65 (32.5) | 39 (19.5) | 6 (3) |

| 16 | 79 (39.5) | 52 (26) | 54 (27) | 15 (7.5) |

| 17 | 85 (42.5) | 64 (32) | 41 (20.5) | 10 (5) |

| Factor | Item | Mean (SD) | Corrected Item–Total Correlation | Cronbach’s Alpha if Item Deleted | Cronbach’s Alpha (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anticipation of trauma | a | 0.39 | 0.67 | 0.73 | |

| b | 0.31 | 0.72 | (0.63–0.81) | ||

| c | 7.91 (2.31) | 0.40 | 0.66 | ||

| d | 0.52 | 0.56 | |||

| Intrusion | 1 | 0.56 | 0.58 | 0.73 | |

| 2 | 0.34 | 0.72 | (0.65–0.82) | ||

| 3 | 6.1 (1.83) | 0.48 | 0.64 | ||

| 4 | 0.70 | 0.48 | |||

| 5 | 0.43 | 0.64 | |||

| Avoidance | 6 | 0.41 | 0.68 | 0.72 | |

| 7 | 4.02 (1.43) | 0.36 | 0.68 | (0.65–0.82) | |

| 8 | 0.34 | 0.58 | |||

| Resignation | 9 | 0.32 | 0.73 | 0.71 | |

| 10 | 0.56 | 0.60 | (0.61–0.79) | ||

| 11 | 5.39 (1.86) | 0.47 | 0.52 | ||

| 12 | 0.37 | 0.59 | |||

| Hyperstimulation | 13 | 0.38 | 0.84 | 0.80 | |

| 14 | 0.68 | 0.72 | (0.75–0.84) | ||

| 15 | 7.48 (2.99) | 0.65 | 0.73 | ||

| 16 | 0.67 | 0.73 | |||

| 17 | 0.69 | 0.72 |

| Intrusion | Avoidance | Resignation | Hyperstimulation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anticipation of trauma | r | 0.48 | 0.36 | 0.21 | 0.30 |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.003 | <0.001 | |

| Intrusion | r | 1.00 | 0.51 | 0.27 | 0.26 |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Avoidance | r | 1.00 | 0.34 | 0.16 | |

| p | <0.001 | 0.021 | |||

| Resignation | r | 1.00 | 0.43 | ||

| p | <0.001 |

| EPDS | ||

|---|---|---|

| Anticipation of trauma | r | 0.37 |

| p | <0.001 | |

| Intrusion | r | 0.33 |

| p | <0.001 | |

| Avoidance | r | 0.06 |

| p | 0.440 | |

| Resignation | r | 0.33 |

| p | <0.001 | |

| Hyperstimulation | r | 0.54 |

| p | <0.001 |

| Anticipation of Trauma (A) | Intrusion (A) | Avoidance (A) | Resignation (A) | Hyperstimulation (A) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anticipation of trauma (Β) | r | 0.40 | 0.32 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.24 |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Intrusion (Β) | r | 0.34 | 0.43 | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.36 |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Avoidance (Β) | r | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.12 |

| p | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.095 | |

| Resignation (Β) | r | 0.14 | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.27 | 0.21 |

| p | 0.043 | 0.002 | 0.003 | <0.001 | 0.002 | |

| Hyperstimulation (Β) | r | 0.26 | 0.35 | 0.27 | 0.35 | 0.49 |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Varela, P.; Zervas, I.; Diamanti, A.; Nanou, C.; Lykeridou, A.; Deltsidou, A. Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms Following Childbirth: A Contribution to the Psychometric Evaluation of the Greek Version of the Traumatic Event Scale (TES) (Version B). Healthcare 2025, 13, 768. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070768

Varela P, Zervas I, Diamanti A, Nanou C, Lykeridou A, Deltsidou A. Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms Following Childbirth: A Contribution to the Psychometric Evaluation of the Greek Version of the Traumatic Event Scale (TES) (Version B). Healthcare. 2025; 13(7):768. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070768

Chicago/Turabian StyleVarela, Pinelopi, Ioannis Zervas, Athina Diamanti, Christina Nanou, Aikaterini Lykeridou, and Anna Deltsidou. 2025. "Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms Following Childbirth: A Contribution to the Psychometric Evaluation of the Greek Version of the Traumatic Event Scale (TES) (Version B)" Healthcare 13, no. 7: 768. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070768

APA StyleVarela, P., Zervas, I., Diamanti, A., Nanou, C., Lykeridou, A., & Deltsidou, A. (2025). Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms Following Childbirth: A Contribution to the Psychometric Evaluation of the Greek Version of the Traumatic Event Scale (TES) (Version B). Healthcare, 13(7), 768. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070768