Mixed Methods Studies on Breastfeeding: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Research Strategy

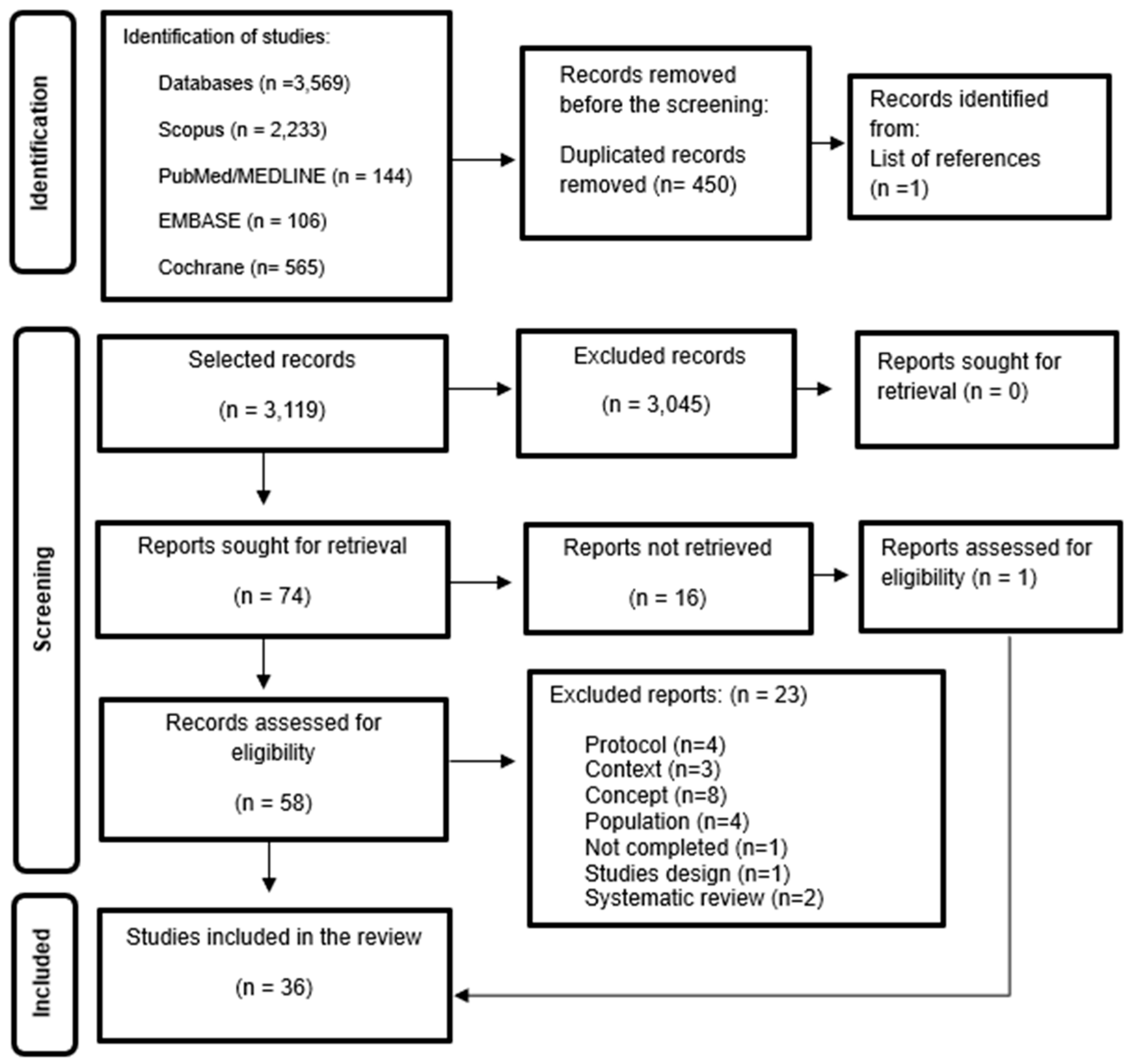

2.4. Studies’ Selection

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Summarizing and Reporting the Results

3. Results

3.1. Breastfeeding Rates and Duration

3.2. Barriers to Breastfeeding

3.2.1. Biological and Physical Barriers

3.2.2. Lack of Support from Family and Friends

3.2.3. Lack of Support from Healthcare Professionals

3.2.4. Skepticism About the Benefits of Breastfeeding

3.2.5. Unfavorable Social and Hospital Environments

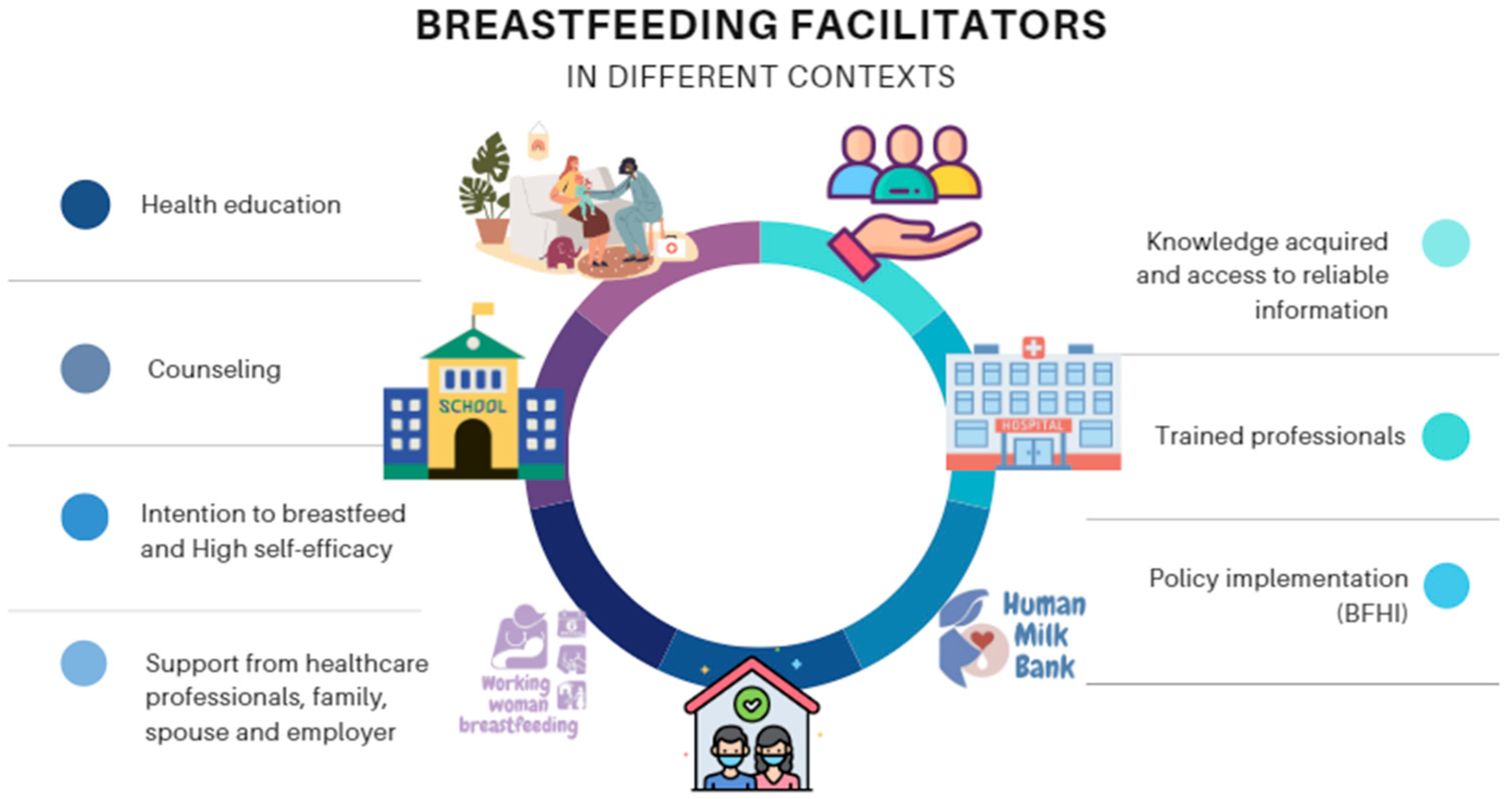

3.3. Facilitators of Breastfeeding

4. Discussion

4.1. Design

4.2. Breastfeeding Rates Across Countries

4.3. Barriers and Facilitators to Breastfeeding

4.4. Limitations of the Studies Included in the Review

5. Limitations of the Review and Scope of Mixed Methods Research

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Froón, A.; Orczyk-Pawiłowicz, M. Breastfeeding Beyond Six Months: Evidence of Child Health Benefits. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, H.; Fatimatasari, F.; Irwanti, W.; Kusuma, C.; Alfiana, R.D.; Asshiddiqi, M.I.N.; Nugroho, S.; Lewis, E.C.; Gittelsohn, J. Exclusive Breastfeeding Protects Young Children from Stunting in a Low-Income Population: A Study from Eastern Indonesia. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajamaa, A.; Mattick, K.; de la Croix, A. How to do mixed-methods research. Clin. Teach. 2020, 17, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohan, S.; Keshvari, M.; Mohammadi, F.; Heidari, Z. Designing and evaluating an empowering program for breastfeeding: A mixed-methods studies. Arch. Iran. Med. 2019, 22, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kwan, J.; Jia, J.; Yip, K.M.; So, H.K.; Leung, S.S.; Ip, P.; Wong, W.H. A mixed-methods studies on the association of six-month predominant breastfeeding with socioecological factors and COVID-19 among experienced breastfeeding women in Hong Kong. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2022, 17, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubuga, C.K.; Tindana, J. Breastfeeding environment and experiences at the workplace among health workers in the Upper East Region of Ghana. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2023, 18, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shobo, O.G.; Umar, N.; Gana, A.; Longtoe, P.; Idogho, O.; Anyanti, J. Factors influencing the early initiation of breast feeding in public primary healthcare facilities in Northeast Nigeria: A mixed-method studies. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e032835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Primo, C.C.; Brandão, M.A.G. Interactive Theory of Breastfeeding: Creation and application of a middle-range theory. Reben—Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2017, 70, 1191–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco van der Sand, I.C.; Silveira, A.D.; Cabral, F.B.; Das Chagas, C.D. A influência da autoeficácia sobre os desfechos do aleitamento materno: Estudo de revisão integrativa. Rev. Contexto Saude 2022, 22, e11677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, V.; Trevisan, I.; Cicolella, D.D.; Waterkemper, R. Systematic review of mixed methods: Method of research for the incorporation of evidence in nursing. Texto Contexto-Enferm. 2019, 28, e20170279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Projeto de Pesquisa: Métodos Qualitativo, Quantitativo e Misto, 5th ed.; Penso: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Aromataris, E.; Munn, Z. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2024; Available online: https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020; Available online: https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL (accessed on 14 January 2020).

- de Oliveira, J.L.C.; de Magalhães, A.M.M.; Matsuda, L.M.; dos Santos, J.L.G.; Souto, R.Q.; Riboldi, C.d.O.; Ross, R. Mixed methods appraisal tool: Strengthening the methodological rigor of mixed methods research studies in nursing. Texto Contexto-Enferm. 2021, 30, e20200603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiravisitkul, P.; Thonginnetra, S.; Kasemlawan, N.; Suntharayuth, T. Supporting factors and structural barriers in the continuity of breastfeeding in the hospital workplace. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2022, 17, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkrumah, J.; Abuosi, A.A.; Nkrumah, R.B. Towards a comprehensive breastfeeding-friendly workplace environment: Insight from selected healthcare facilities in the central region of Ghana. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, M.M.; Sebastian, R.A.; Sebesta, E.; McConnell, A.E.; McKinney, C.R. Missed Opportunities in the Outpatient Pediatric Setting to Support Breastfeeding: Results from a Mixed-Methods Studies. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2019, 33, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, J. The Attitude of UAE Mothers towards Breastfeeding in Abu Dhabi. Texila Int. J. Public Health 2020, 8, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuampa, S.; Ratinthorn, A.; Patil, C.L.; Kuesakul, K.; Prasong, S.; Sudphet, M. Impact of personal and environmental factors affecting exclusive breastfeeding practices in the first six months during the COVID-19 pandemic in Thailand: A mixed-methods approach. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2022, 17, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucker, C.M.; Wilson, E.K.; Samandari, G. Infant feeding experiences among teen mothers in North Carolina: Findings from a mixed-methods studies. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2011, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadakia, A.; Joyner, B.; Tender, J.; Oden, R.; Moon, R.Y. Breastfeeding in African Americans May Not Depend on Sleep Arrangement. Clin. Pediatr. 2014, 54, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, J. A mixed methods evaluation of peer support in Bristol, UK: Mothers’, midwives’ and peer supporters’ views and the effects on breastfeeding. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013, 13, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, L.; Anggrahini, S.M.; Woda, R.R.; Ayton, J.E.; Beggs, S. Exclusive Breastfeeding and the Acceptability of Donor Breast Milk for Sick, Hospitalized Infants in Kupang, Nusa Tenggara Timur, Indonesia. J. Hum. Lact. 2016, 32, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witten, C.; Claasen, N.; Kruger, H.S.; Coutsoudis, A.; Grobler, H. Psychosocial barriers and enablers of exclusive breastfeeding: Lived experiences of mothers in low-income townships, North West Province, South Africa. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2020, 15, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felder, T.M.; Cayir, E.; Nkwonta, C.A.; Tucker, C.M.; Harris, E.H.; Jackson, J.R. A Mixed-Method Feasibility Studies of Breastfeeding Attitudes among Southern African Americans. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2021, 44, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, A.L.; Carrara, V.I.; Paw, M.K.; Malika Dahbu, C.; Gross, M.M.; Stuetz, W.; Nosten, F.H.; McGready, R. High initiation and long duration of breastfeeding despite absence of early skin-to-skin contact in Karen refugees on the Thai-Myanmar border: A mixed methods studies. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2012, 7, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agunbiade, O.M.; Ogunleye, O.V. Constraints to exclusive breastfeeding practice among breastfeeding mothers in Southwest Nigeria: Implications for scaling up. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2012, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörnemann, J.; Kelly, A.H. “It is me who eats, to nourish him”: A mixed-method studies of breastfeeding in post-earthquake Haiti. Matern. Child Nutr. 2012, 9, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maonga, A.R.; Mahande, M.J.; Damian, D.J.; Msuya, S.E. Factors Affecting Exclusive Breastfeeding among Women in Muheza District Tanga Northeastern Tanzania: A Mixed Method Community Based Studies. Matern. Child Health J. 2015, 20, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamoun, C.; Spatz, D. Influence of Islamic Traditions on Breastfeeding Beliefs and Practices Among African American Muslims in West Philadelphia: A Mixed-Methods Studies. J. Hum. Lact. 2017, 34, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feenstra, M.M.; Jørgine Kirkeby, M.; Thygesen, M.; Danbjørg, D.B.; Kronborg, H. Early breastfeeding problems: A mixed method studies of mothers’ experiences. Sex. Reprod. Healthc. 2018, 16, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xin, T.; Gaoshan, J.; Li, Q.; Zou, K.; Tan, S.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, H.; et al. The association between work related factors and breastfeeding practices among Chinese working mothers: A mixed-method approach. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2019, 14, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, H.; McLelland, G.; Gilmour, C.; Cant, R. ‘It’s those first few weeks’: Women’s views about breastfeeding support in an Australian outer metropolitan region. Women Birth 2014, 27, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hookway, L.; Brown, A. Barriers to optimal breastfeeding of medically complex children in the UK paediatric setting: A mixed methods survey of healthcare professionals. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2023, 36, 1857–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irmawati, I.; Nugraheni, S.A.; Sulistiyani, S.; Sriatmi, A. Finding the Needs of Breastfeeding Mother Accompaniment for Successful Exclusive Breastfeeding Until 6 Months in Semarang City: A Mixed Method. BIO Web Conf. 2022, 54, 00004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsdottir, R.B.; Flacking, R.; Jonsdottir, H. Breastfeeding initiation, duration, and experiences of mothers of late preterm twins: A mixed-methods studies. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2022, 17, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saade, S.; Flacking, R.; Ericson, J. Parental experiences and breastfeeding outcomes of early support to new parents from family health care centres—A mixed method studies. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Breevoort, D.; Tognon, F.; Beguin, A.; Ngegbai, A.S.; Putoto, G.; van den Broek, A. Determinants of breastfeeding practice in Pujehun district, southern Sierra Leone: A mixed-method studies. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2021, 16, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, L.K.; Mason, K.A.; Mepham, E.; Sharkey, K.M. A mixed methods studies of perinatal sleep and breastfeeding outcomes in women at risk for postpartum depression. Sleep Health 2021, 7, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papautsky, E.L.; Koenig, M.D. A mixed-methods examination of inpatient breastfeeding education using a human factors perspective. Breastfeed. Med. 2021, 16, 947–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Fiese, B.H.; Donovan, S.M. Breastfeeding is natural but not the cultural norm: A mixed-methods studies of first-time breastfeeding, african american mothers participating in WIC. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2017, 49, S151–S161.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Cordero, S.; Lozada-Tequeanes, A.L.; Fernández-Gaxiola, A.C.; Shamah-Levy, T.; Sachse, M.; Veliz, P.; Cosío-Barroso, I. Barriers and facilitators to breastfeeding during the immediate and one month postpartum periods, among Mexican women: A mixed methods approach. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2020, 15, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericson, J.; Palmér, L. Cessation of breastfeeding in mothers of preterm infants—A mixed method studies. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Younger, K.M.; Cassidy, T.M.; Wang, W.; Kearney, J.M. Breastfeeding practices 2008–2009 among Chinese mothers living in Ireland: A mixed methods studies. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juntereal, N.A.; Spatz, D.L. Breastfeeding experiences of same-sex mothers. Birth 2019, 47, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, J. The Effect of Knowledge on Breastfeeding among Mothers’ in Abu Dhabi. Texila Int. J. Public Health 2020, 8, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnow, B.S.; Pandey, S.K.; Luo, Q.E. Como a pesquisa de métodos mistos pode melhorar a relevância política das avaliações de impacto. Eval. Rev. 2024, 48, 495–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, S.; Nowell, L.; Moules, N.J. Interpretive description in applied mixed methods research: Exploring issues of fit, purpose, process, context, and design. Nurs. Inq. 2023, 30, e12542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluye, P.; Hong, Q.N. Combining the Power of Stories and the Power of Numbers: Mixed Methods Research and Mixed Studies Reviews. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojgan, J.; Shirin, O.; Kazemi, A. Development of an exclusive breastfeeding intervention based on the theory of planned behavior for mothers with preterm infants: Studies protocol for a mixed methods studies. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2023, 12, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomori, C. Overcoming Barriers to Breastfeeding. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2022, 83, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleason, S.; Wilkin, M.K.; Sallack, L.; Whaley, S.E.; Martinez, C.; Paolicelli, C. A duração da amamentação está associada às práticas de apoio à amamentação no nível do WIC no nível do site. J. Educ. Nutr. Comport. 2020, 52, 680–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neifert, M.; Bunik, M. Overcoming Clinical Barriers to Exclusive Breastfeeding. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2013, 60, 115–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | N° (Cases) | % (Approximate Value) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 2011 | 1 | 2.8% |

| 2012 | 2 | 5.6% | |

| 2013 | 2 | 5.6% | |

| 2015 | 2 | 5.6% | |

| 2016 | 2 | 5.6% | |

| 2017 | 1 | 2.8% | |

| 2018 | 2 | 5.6% | |

| 2019 | 3 | 8.2% | |

| 2020 | 8 | 22.2% | |

| 2021 | 4 | 11% | |

| 2022 | 7 | 19.4% | |

| 2023 | 2 | 5.6% | |

| Country | United States | 7 | 19.4% |

| United Kingdom | 2 | 5.6% | |

| Thailand | 3 | 8.2% | |

| Australia | 1 | 2.8% | |

| South Africa | 1 | 2.8% | |

| Tanzania | 1 | 2.8% | |

| Ghana | 2 | 5.6% | |

| Sierra Leone | 1 | 2.8% | |

| China | 2 | 5.6% | |

| Mexico | 2 | 5.6% | |

| Iran | 1 | 2.8% | |

| Ireland | 1 | 2.8% | |

| Iceland | 2 | 5.6% | |

| Indonesia | 2 | 5.6% | |

| Sweden | 2 | 5.6% | |

| Nigeria | 2 | 5.6% | |

| Denmark | 1 | 2.8% | |

| Haiti | 1 | 2.8% | |

| United Arab Emirates | 2 | 5.6% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Minarini, G.; Lima, E.; Figueiredo, K.; Pereira, N.; Carmona, A.P.; Bueno, M.; Primo, C. Mixed Methods Studies on Breastfeeding: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 746. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070746

Minarini G, Lima E, Figueiredo K, Pereira N, Carmona AP, Bueno M, Primo C. Mixed Methods Studies on Breastfeeding: A Scoping Review. Healthcare. 2025; 13(7):746. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070746

Chicago/Turabian StyleMinarini, Greyce, Eliane Lima, Karla Figueiredo, Nayara Pereira, Ana Paula Carmona, Mariana Bueno, and Cândida Primo. 2025. "Mixed Methods Studies on Breastfeeding: A Scoping Review" Healthcare 13, no. 7: 746. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070746

APA StyleMinarini, G., Lima, E., Figueiredo, K., Pereira, N., Carmona, A. P., Bueno, M., & Primo, C. (2025). Mixed Methods Studies on Breastfeeding: A Scoping Review. Healthcare, 13(7), 746. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070746