Perspectives on Physician-Assisted Suicide Among German Hospice Professionals: Findings from a Diagnostic Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Data Collection Procedure

2.3. Survey Instrument

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PAS | Physician-Assisted Suicide |

| LCA | Latent Class Analysis |

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| CAIC | Consistent Akaike Information Criterion |

| BIC | Bayesian Information Criterion |

| SABIC | Sample-Size Adjusted BIC |

| AIC3 | AIC With a Third Penalty Term |

| χ2 | Chi-Square |

| G2 | G-Squared |

References

- Mroz, S.; Dierickx, S.; Deliens, L.; Cohen, J.; Chambaere, K. Assisted Dying around the World: A Status Quaestionis. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2021, 10, 3540–3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujioka, J.K.; Mirza, R.M.; McDonald, P.L.; Klinger, C.A. Implementation of Medical Assistance in Dying: A Scoping Review of Health Care Providers’ Perspectives. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2018, 55, 1564–1576.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitta, A.; Ecker, F.; Zeilinger, E.L.; Kum, L.; Adamidis, F.; Masel, E.K. Statements of Austrian Hospices and Palliative Care Units after the Implementation of the Law on Assisted Suicide. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2024, 136, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Bruchem-van de Scheur, G.G.; Van Der Arend, A.J.G.; Spreeuwenberg, C.; Huijer Abu-Saad, H.; Ter Meulen, R.H.J. Euthanasia and Physician-assisted Suicide in the Dutch Homecare Sector: The Role of the District Nurse. J. Adv. Nurs. 2007, 58, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, L.; Spieß, L.; Wagner, B. What Do Suicide Loss Survivors Think of Physician-Assisted Suicide: A Comparative Analysis of Suicide Loss Survivors and the General Population in Germany. BMC Med. Ethics 2024, 25, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutscher Bundestag. Bundestag lehnt Gesetzentwürfe zur Reform der Sterbehilfe ab. Bundestag.de. 2023. Available online: https://www.bundestag.de/dokumente/textarchiv/2023/kw27-de-suiziddebatte-954918 (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Tagesschau. Interview zur Regelung der Sterbehilfe: “An vielen Stellen kann Menschen Geholfen Werden”. Tagesschau.de. 2023. Available online: https://www.tagesschau.de/wissen/gesundheit/sterbehilfe-debatte-bundestag-ethikrat-buyx-100.html (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Schwabe, S.; Herbst, F.A.; Stiel, S.; Schneider, N. Suicide Assistance in Germany: A Protocol for a Multi-Perspective Qualitative Study to Explore the Current Practice. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0311880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahaddour, C.; Van den Branden, S.; Broeckaert, B. “God Is the Giver and Taker of Life”: Muslim Beliefs and Attitudes Regarding Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia. AJOB Empir. Bioeth. 2018, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magelssen, M.; Supphellen, M.; Nortvedt, P.; Materstvedt, L.J. Attitudes towards Assisted Dying Are Influenced by Question Wording and Order: A Survey Experiment. BMC Med. Ethics 2016, 17, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonacci, R.; Baxter, S.; Henderson, J.D.; Mirza, R.M.; Klinger, C.A. Hospice Palliative Care (HPC) and Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD): Results from a Canada-Wide Survey. J. Palliat. Care 2021, 36, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavoie, M.; Godin, G.; Vézina-Im, L.-A.; Blondeau, D.; Martineau, I.; Roy, L. Psychosocial Determinants of Physicians’ Intention to Practice Euthanasia in Palliative Care. BMC Med. Ethics 2015, 16, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganzini, L.; Harvath, T.A.; Jackson, A.; Goy, E.R.; Miller, L.L.; Delorit, M.A. Experiences of Oregon Nurses and Social Workers with Hospice Patients Who Requested Assistance with Suicide. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 347, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, M.; Ostroff, C.; Wilson, M.E.; Wiechula, R.; Cusack, L. Profiles of Intended Responses to Requests for Assisted Dying: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 124, 104069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeilinger, E.L.; Petersen, A.; Brunevskaya, N.; Fuchs, A.; Wagner, T.; Pietschnig, J.; Kitta, A.; Ecker, F.; Kum, L.; Adamidis, F.; et al. Experiences and Attitudes of Nurses with the Legislation on Assisted Suicide in Austria. Palliat. Support. Care 2024, 22, 2022–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unseld, M.; Meyer, A.L.; Vielgrader, T.-L.; Wagner, T.; König, D.; Popinger, C.; Sturtzel, B.; Kreye, G.; Zeilinger, E.L. Assisted Suicide in Austria: Nurses’ Understanding of Patients’ Requests and the Role of Patient Symptoms. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerson, S.M.; Bingley, A.; Preston, N.; Grinyer, A. When Is Hastened Death Considered Suicide? A Systematically Conducted Literature Review about Palliative Care Professionals’ Experiences Where Assisted Dying Is Legal. BMC Palliat. Care 2019, 18, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorsuch, N. The Future of Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.Y.H.; De Vries, R.G.; Peteet, J.R. Euthanasia and Assisted Suicide of Patients with Psychiatric Disorders in the Netherlands 2011 to 2014. JAMA Psychiatry 2016, 73, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orentlicher, D. The Legal and Ethical Basis for Physician-Assisted Death. Indiana Health Law Rev. 2017, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Dubus, N. Who Cares for the Caregivers? Why Medical Social Workers Belong on End-of-Life Care Teams. Soc. Work Health Care 2010, 49, 603–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babbie, E. The Practice of Social Research, 14th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Brodziak, A.; Sigorski, D.; Osmola, M.; Wilk, M.; Gawlik-Urban, A.; Kiszka, J.; Machulska-Ciuraj, K.; Sobczuk, P. Attitudes of Patients with Cancer towards Vaccinations—Results of Online Survey with Special Focus on the Vaccination against COVID-19. Vaccines 2021, 9, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Collins, L.M.; Lanza, S.T. Latent Class and Latent Transition Analysis: With Applications in the Social, Behavioral, and Health Sciences; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gothe, H.; Brinkmann, C.; Schmedt, N.; Walker, J.; Ohlmeier, C. Is There an Unmet Medical Need for Palliative Care Services in Germany? Incidence, Prevalence, and 1-Year All-Cause Mortality of Palliative Care Sensitive Conditions: Real-World Evidence Based on German Claims Data. J. Public Health 2022, 30, 711–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thönnes, M.; Jakoby, N. Development of Hospice and Palliative Care Services in Germany. A Case Study. Palliat. Med. Care 2016, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nassehi, A.; Saake, I.; Breitsameter, C.; Bauer, A.; Barth, N.; Reis, I. Adding Spontaneity to Organizations—What Hospice Volunteers Contribute to Everyday Life in German Inpatient Hospice and Palliative Care Units: A Qualitative Study. BMC Palliat. Care 2024, 23, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, P.; Calfee, C.S.; Delucchi, K.L. Practitioner’s Guide to Latent Class Analysis: Methodological Considerations and Common Pitfalls. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 49, e63–e79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Percentage (%) or Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 64.2 |

| Male | 35.8 |

| Age | |

| Years | 46.3 (9.7) |

| Marital Status | |

| Married/Partnership | 63.5 |

| Single | 24.8 |

| Divorced/Widowed | 11.7 |

| Educational Background | |

| Nursing/Healthcare | 68.1 |

| Advanced Degrees | 18.4 |

| Other Training | 13.5 |

| Work Experience (years) | 12.7 (6.4) |

| Religious Affiliation | |

| Christian | 56.3 |

| No Affiliation | 32.9 |

| Other Religions/Spiritual | 10.8 |

| Exposure to Assisted Suicide Discussions | |

| Rarely | 54.3 |

| Occasionally | 31.2 |

| Never | 8 |

| Often | 6.5 |

| Question | Never (1) | Rarely (2) | Neutral (3) | Often (4) | Very Often (5) |

| 1. How often have patients approached you to discuss assisted suicide? | 33.9 | 54.3 | 4.5 | 6.5 | 0.8 |

| Question | Strongly disagree (1) | Somewhat disagree (2) | Neutral (3) | Somewhat agree (4) | Strongly agree (5) |

| 2. Assisted suicide aligns with my personal values. | 12.7 | 24.6 | 14.7 | 28.9 | 19.1 |

| 3. Assisted suicide is not compatible with my faith, spirituality, or religion. | 40.7 | 19.7 | 11.3 | 16.5 | 11.8 |

| 4. I would accompany a patient during the process of assisted suicide. | 27.2 | 16.8 | 9.3 | 27.8 | 18.9 |

| 5. Assisted suicide can be prematurely viewed as a potential solution rather than the absolute last resort in a hopeless situation. | 6.5 | 14.5 | 7.9 | 39.2 | 31.9 |

| 6. Patients’ and relatives’ trust in the quality of care may decrease after the implementation of assisted suicide. | 17.6 | 27.2 | 19.7 | 21.7 | 13.8 |

| 7. Assisted suicide may lead to new demanding tasks that will further increase my workload. | 7.2 | 14.5 | 22.8 | 32.6 | 22.9 |

| 8. In the new work situation shaped by assisted suicide, I may quickly become mentally burdened. | 8.2 | 23.5 | 13.3 | 34.1 | 20.9 |

| 9. Assisted suicide may lead to increased conflicts with patients. | 11.8 | 29.7 | 20.3 | 31.7 | 6.5 |

| Question | Very low (1) | Rather low (2) | Neutral (3) | Rather high (4) | Very high (5) |

| 10. How would you assess your knowledge of the procedures and the resulting requirements for hospice work about assisted suicide? | 11.3 | 21.7 | 32.3 | 26.9 | 7.8 |

| Question | Strongly disagree (1) | Somewhat disagree (2) | Neutral (3) | Somewhat agree (4) | Strongly agree (5) |

| 11. I can recognize and appropriately address the needs of patients considering assisted suicide. | 5 | 12.4 | 20.8 | 46 | 15.8 |

| 12. I can discuss a patient’s desire for assisted suicide openly and without judgment. | 2 | 2.3 | 11.8 | 41.6 | 42.3 |

| 13. There are preliminary considerations for adapting organizational structures in the hospice where I work regarding the implementation of assisted suicide. | 51.4 | 26.7 | 13.4 | 6.2 | 2.3 |

| Class | AIC | AIC3 | BIC | SABIC | CAIC | Log-Likelihood | Χ2 | G2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20,591 | 20,643 | 20,815 | 20,650 | 20,867 | –10,243 | 7.19 | 13,434 |

| 2 | 19,717 | 19,824 | 20,180 | 19,840 | 20,287 | –9752 | 2.39 | 12,452 |

| 3 | 19,039 | 19,201 | 20,040 | 19,326 | 20,202 | –9308 | 1.18 | 11,570 |

| 4 | 19,370 | 19,587 | 20,309 | 19,620 | 20,526 | –9468 | 1.65 | 11,951 |

| 5 | 19,148 | 19,420 | 20,324 | 19,461 | 20,596 | –9502 | 1.09 | 11,987 |

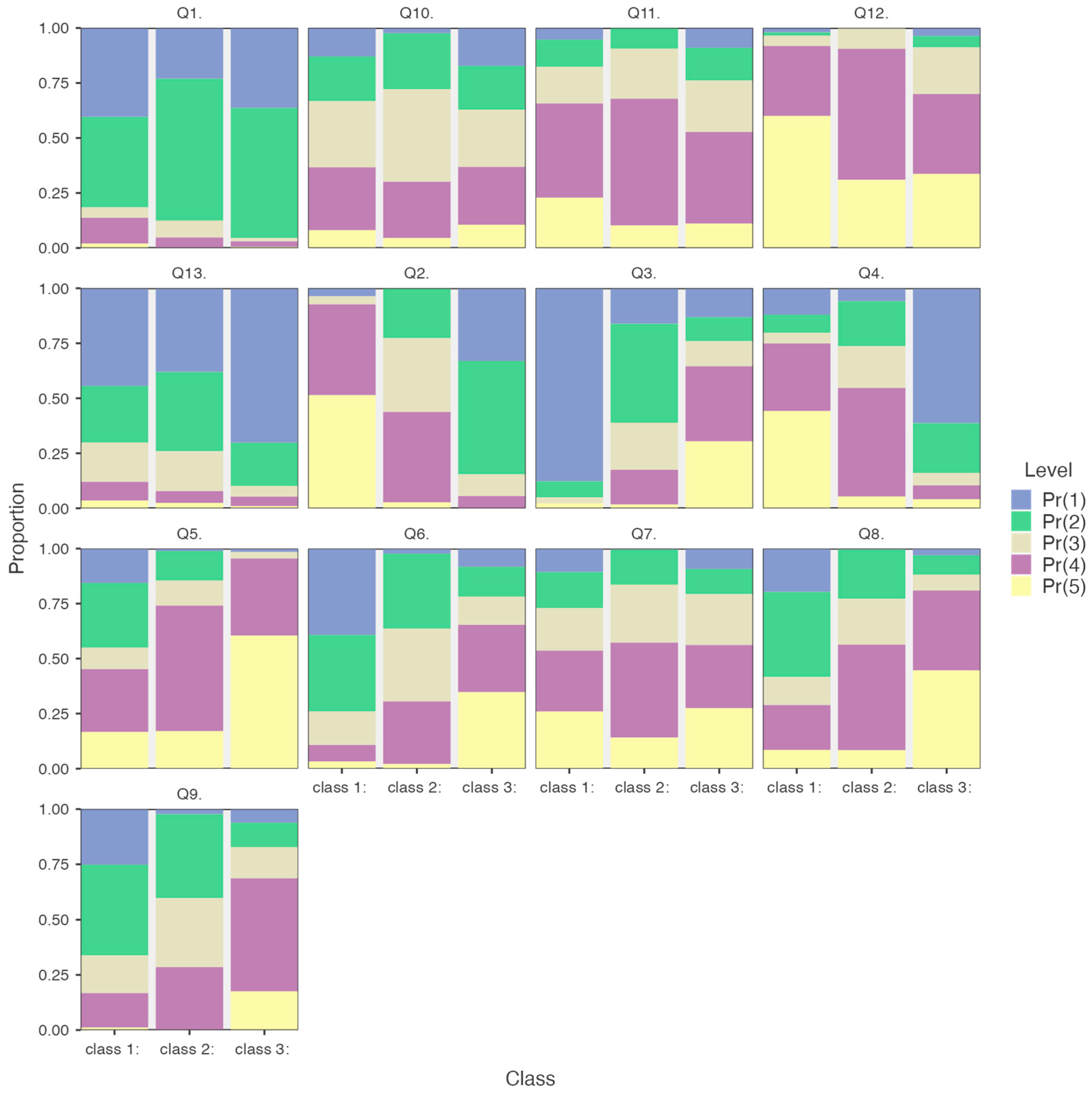

| Question | A: Class 1 (M ± SD); n = 198 | B: Class 2 (M ± SD); n = 164 | C: Class 3 (M ± SD); n = 196 | F(2,359) | Post-Hoc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 1.93 (1.05) | 1.95 (0.71) | 1.72 (0.67) | 5.42 ** | A > C *, B > C * |

| 2. | 4.4 (0.85) | 3.23 (0.8) | 1.88 (0.8) | 461.65 *** | A > B ***, A > C ***, B > C *** |

| 3. | 1.2 (0.67) | 2.43 (0.98) | 3.57 (1.37) | 273.92 *** | A < B ***, A < C ***, B < C *** |

| 4. | 3.88 (1.37) | 3.32 (0.99) | 1.68 (1.1) | 184.63 *** | A > B ***, A > C ***, B > C *** |

| 5. | 2.99 (1.36) | 3.76 (0.93) | 4.53 (0.7) | 113.39 *** | A < B ***, A < C ***, B < C *** |

| 6. | 1.98 (1.04) | 2.93 (0.9) | 3.71 (1.28) | 112.86 *** | A < B ***, A < C ***, B < C *** |

| 7. | 3.44 (1.32) | 3.54 (0.93) | 3.52 (1.27) | 0.35 | -- |

| 8. | 2.59 (1.24) | 3.39 (0.94) | 4.12 (1.07) | 86.31 *** | A < B ***, A < C ***, B < C *** |

| 9. | 2.26 (1.04) | 2.84 (0.85) | 3.63 (1.08) | 82.91 *** | A < B ***, A < C ***, B < C *** |

| 10. | 2.98 (1.16) | 3.02 (0.91) | 2.95 (1.24) | 0.23 | -- |

| 11. | 3.65 (1.12) | 3.68 (0.8) | 3.33 (1.12) | 6.59 ** | A > C **, B > C ** |

| 12. | 4.45 (0.83) | 4.23 (0.6) | 3.92 (1.04) | 15.48 *** | A > B *, A > C ***, B > C ** |

| 13. | 2.01 (1.14) | 1.99 (0.99) | 1.46 (0.86) | 21.31 *** | A > C ***, B > C *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Surzykiewicz, J.; Toussaint, L.L.; Riedl, E.; Harder, J.-P.; Loichen, T.; Büssing, A.; Maier, K.; Skalski-Bednarz, S.B. Perspectives on Physician-Assisted Suicide Among German Hospice Professionals: Findings from a Diagnostic Survey. Healthcare 2025, 13, 763. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070763

Surzykiewicz J, Toussaint LL, Riedl E, Harder J-P, Loichen T, Büssing A, Maier K, Skalski-Bednarz SB. Perspectives on Physician-Assisted Suicide Among German Hospice Professionals: Findings from a Diagnostic Survey. Healthcare. 2025; 13(7):763. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070763

Chicago/Turabian StyleSurzykiewicz, Janusz, Loren L. Toussaint, Elisabeth Riedl, Jean-Pierre Harder, Teresa Loichen, Arndt Büssing, Kathrin Maier, and Sebastian Binyamin Skalski-Bednarz. 2025. "Perspectives on Physician-Assisted Suicide Among German Hospice Professionals: Findings from a Diagnostic Survey" Healthcare 13, no. 7: 763. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070763

APA StyleSurzykiewicz, J., Toussaint, L. L., Riedl, E., Harder, J.-P., Loichen, T., Büssing, A., Maier, K., & Skalski-Bednarz, S. B. (2025). Perspectives on Physician-Assisted Suicide Among German Hospice Professionals: Findings from a Diagnostic Survey. Healthcare, 13(7), 763. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070763