The Relationship Between Korean Adolescents’ Happiness and Depression: The Mediating Effect of Teacher Relationships and Moderated Mediation of Peer and Parental Relationships and Parental Attitudes

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What are the relationships between happiness, teacher relationships, depression, peer relationships, and parental attitudes as perceived by adolescents before and after entering high school?

- Do teacher relationships mediate the relationship between happiness and depression as perceived by adolescents before and after entering high school?

- Do peer relationships and parental attitudes exhibit moderated mediation effects on the relationship between happiness and teacher relationships as perceived by adolescents before and after entering high school?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Data Collection

2.2. Measurement Instruments

2.2.1. Happiness

2.2.2. Teacher Relationships

2.2.3. Depression

2.2.4. Peer Relationships

2.2.5. Parental Attitudes

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

3.2. Mediating Effect of Teacher Relationships on the Relationship Between Happiness and Depression

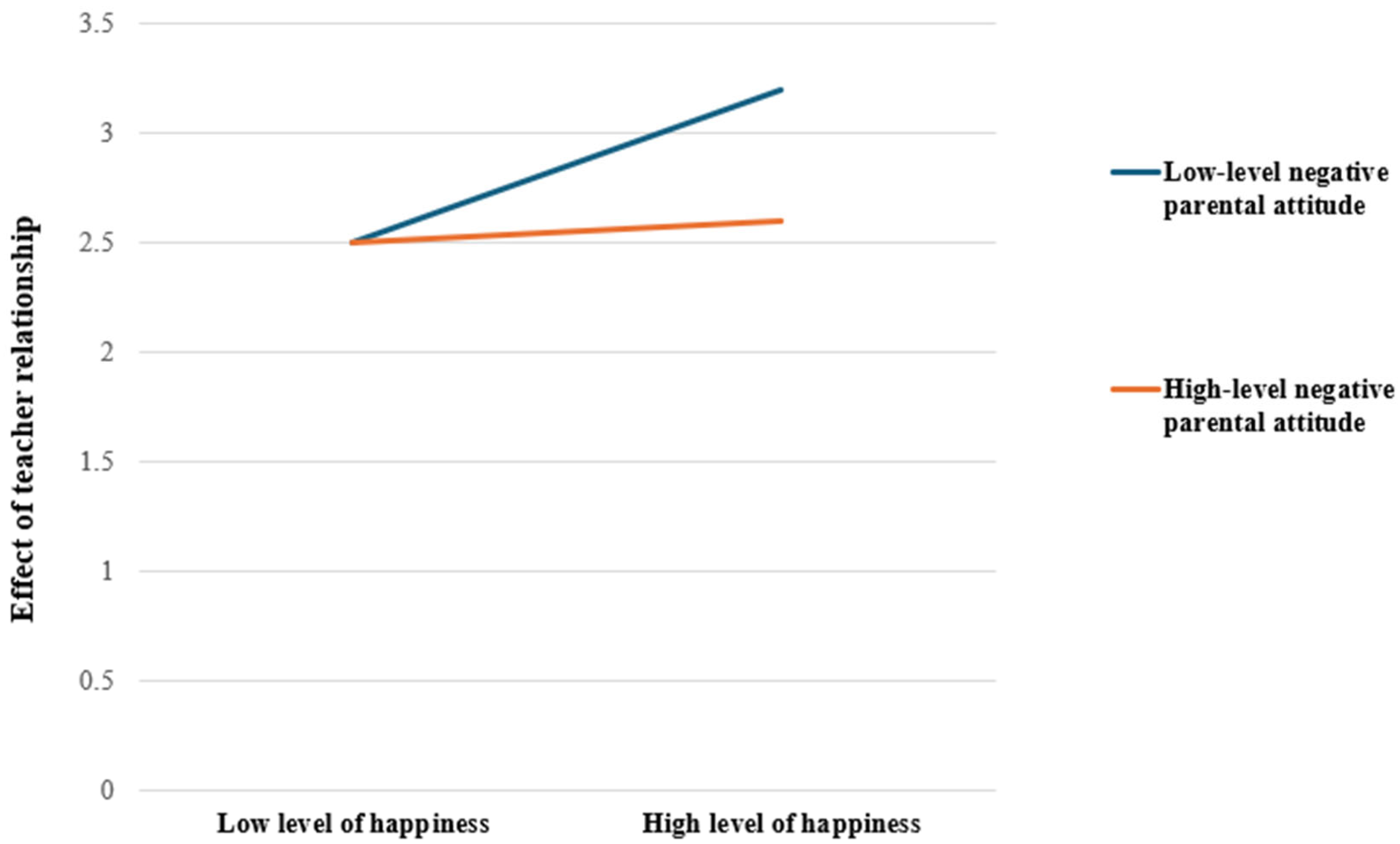

3.3. Moderating Effect of Peer Relationships (Positive/Negative) and Parental Attitudes (Positive/Negative) on Happiness and Teacher Relationships

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kyriazos, T.; Poga, M. Redefining parental dynamics: Exploring mental health, happiness, and positive parenting practices. Fam. Process 2025, 64, e70003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yonsei University Institute for Social Development. The 12th International Comparative Study on Children’s and Adolescents’ Happiness Index; Yonsei University Institute for Social Development: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Heo, J.; Lin, S.F.; Kondo, N.; Hwang, J.; Lee, J.K.; Oh, J. Values and happiness among Asian adolescents: A cross-national study. J. Youth Stud. 2019, 22, 420–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Research Institute. Korean Social Trends 2023. Statistics Korea. 2023. Available online: https://kostat.go.kr/menu.es?mid=a90104010100 (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Lee, R.; Oh, C.; Chae, H. The moderating effect of happiness on the influence of daily stress on mental health among adolescents in multicultural families. Inst. Humanit. Soonchunhyang Univ. 2019, 38, 123–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Park, J.; Heo, N. Latent profile classification of depression and self-esteem during adolescence and differences in subjective well-being. J. Future Youth Stud. 2023, 20, 77–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Kim, J.; Noh, S. Factors affecting adolescents’ subjective well-being: Analysis of data from the 10th Youth Health Behavior Online Survey, 2014. J. Korean Soc. Ind. Acad. Res. 2015, 16, 7656–7666. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, B. The analysis on structural relationships with stress, self-esteem, depression, and happiness in adolescents. J. Korean Soc. Wellness 2021, 16, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.S.; Bae, S.W.; Park, K.J.; Seo, M.K.; Kim, H.J. A structural analysis of the relationship between peer attachment, social withdrawal, depression, and school adjustment. Health Soc. Welf. Rev. 2017, 37, 72–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretherton, I. The Origins of Attachment Theory: John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth. Dev. Psychol. 1992, 28, 759–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.J.; Collie, R.J. Teacher–student relationships and students’ engagement in high school: Does the number of negative and positive relationships with teachers matter? J. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 111, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, J.E.; Kochendorfer, L.B.; Stuart-Parrigon, K.L.; Koehn, A.J.; Kerns, K.A. Parent–child attachment and children’s experience and regulation of emotion: A meta-analytic review. Emotion 2019, 19, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Call to Broaden and Build Mikulincer and Shaver’s Work on the Benefits of Priming Attachment Security. Psychol. Inq. 2007, 18, 168–172. [CrossRef]

- Nazish, A.; Kang, M.A.; Fatima, S.R. Exploring the Positive Teacher-Student Relationship on Students’ Motivation and Academic Performance in Secondary Schools in Karachi. Acad. Educ. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2024, 4, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Xia, Y. A study of interpersonal relationships and mental health in adolescence. Lect. Notes Educ. Psychol. Public Media 2024, 60, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Lim, S. The relationship between parental psychological control and relational aggression of adolescents: Moderated mediation effects of moral disengagement and peer pressure. J. Educ. Ther. 2020, 12, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traylor, A.C.; Williams, J.D.; Kenney, J.L.; Hopson, L.M. Relationships between adolescent well-being and friend support and behavior. Child. Sch. 2016, 38, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çıkrıkçı, Ö.; Erzen, E. Academic procrastination, school attachment, and life satisfaction: A mediation model. J. Ration. Emot. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2020, 38, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Park, C. Social support and psychological well-being in younger and older adults: The mediating effects of basic psychological need satisfaction. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1051968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamat, K. Parenting styles and their effect on child development. Int. J. Artif. Intell. 2024, 4, 410–413. [Google Scholar]

- Lucktong, A.; Salisbury, T.T.; Chamratrithirong, A. The impact of parental, peer and school attachment on the psychological well-being of early adolescents in Thailand. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2018, 23, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izzo, F.; Baiocco, R.; Pistella, J. Children’s and adolescents’ happiness and family functioning: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, S.T.; Baharudin, R. The relationship between adolescents’ perceived parental involvement, self-efficacy beliefs, and subjective well-being: A multiple mediator model. Soc. Indic. Res. 2016, 126, 257–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y. The relationships of adolescent academic stress, school violence and subjective happiness: Focusing on the mediating pathway of friend, family and teacher’s support. J. Soc. Sci. 2017, 43, 263–289. [Google Scholar]

- Noh, J.U.; Choi, J.Y. The influence of excessive smart phone use on happiness among elementary school children in higher grade: Mediating effects of social relationship. J. Learn.-Cent. Curric. Instr. 2019, 19, 1265–1286. [Google Scholar]

- National Youth Policy Institute. Korea Children and Youth Panel Survey 2018 (KCYPS 2018-). Available online: https://www.nypi.re.kr/archive/board?menuId=MENU00329 (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Lee, J.R.; Kim, G.S.; Song, S.Y.; Yi, Y.; Kim, J.M.; Kim, S.A.; Kim, S.K. Panel Study on Korean Children 2015; Korea Institute of Child Care and Education: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.B.; Kim, N.H. Validation of student-teacher attachment relationship scale (STARS) as a basis for evaluating teachers’ educational competencies. Korean J. Educ. Psychol. 2009, 23, 697–714. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.K.; Back, H.J.; Lim, H.J.; Lee, G.O. Korean Children & Youth Panel Survey 2010; National Youth Policy Institute: Sejong City, Republic of Korea, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, S.M.; Hong, J.Y.; Hyun, M.H. A validation study of the peer relationship quality scale for adolescents. Korean J. Youth Stud. 2015, 22, 325–344. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T.; Lee, E. Validation of the Korean version of parents as social context questionnaire for adolescents: PSCQ_KA. Korean J. Youth Stud. 2017, 24, 313–333. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Curran, P.J.; West, S.G.; Finch, J.F. The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychol. Methods 1996, 1, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, G.R.; Mueller, R.O. (Eds.) Structural Equation Modeling: A Second Course, 2nd ed.; IAP Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Furman, W.; Buhrmester, D. Age and sex differences in perceptions of networks of personal relationships. Child. Dev. 1992, 63, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Wills, T.A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 98, 310–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garmezy, N.; Masten, A.S.; Tellegen, A. The study of stress and competence in children: A building block for developmental psychopathology. Child. Dev. 1984, 55, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. A Secure Base: Parent-Child Attachment and Healthy Human Development; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Xie, Y. The influence of family background on educational expectations: A comparative study. Chin. Sociol. Rev. 2020, 52, 269–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.H.; Kwak, T.H. The impact of academic stress on depression among Korean and Chinese adolescents: Focusing on the parallel mediating effects of cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression. Korean J. Youth Stud. 2024, 35, 5–33. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.S.; Yoon, W.S. A study on changes in parenting attitudes through parent education workshops. Enneagr. Res. 2013, 10, 61–77. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, T.H.; Han, C.S.; Kim, B.Y. The impact of parental neglect and abuse on adolescents’ emotional problems: Focusing on the mediating effects of self-esteem and teacher relationships. Korean J. Sch. Psychol. 2019, 16, 382–400. [Google Scholar]

- Eryilmaz, A. Perceived personality traits and types of teachers and their relationship to the subjective well-being and academic achievements of adolescents. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 2014, 14, 2049–2062. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1050487.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Sointu, E.T.; Savolainen, H.; Lappalainen, K.; Lambert, M.C. Longitudinal associations of student–teacher relationships and behavioural and emotional strengths on academic achievement. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 37, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.M. Structural relationships among parents’ positive and negative parenting attitudes, teacher attachment, and academic enthusiasm. J. Korean Assoc. Learn.-Cent. Curric. Instr. 2020, 20, 915–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porumbu, D.; Necşoi, D.V. Relationship between parental involvement/attitude and children’s school achievements. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 76, 706–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toumbourou, J.W.; Gregg, M.E. Impact of an empowerment-based parent education program on the reduction of youth suicide risk factors. J. Adolesc. Health 2002, 31, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Li, X.; Stanton, B. Perceptions of parent–adolescent communication within families: It is a matter of perspective. Psych. Health Med. 2011, 16, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roach, A. Supportive peer relationships and mental health in adolescence: An integrative review. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2018, 39, 723–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uslu, F.; Gizir, S. School belonging of adolescents: The role of teacher–student relationships, peer relationships and family involvement. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 2017, 17, 63–82. [Google Scholar]

- Corso, M.J.; Bundick, M.J.; Quaglia, R.; Haywood, D.E. Where student, teacher, and content meet: Student engagement in the secondary school classroom. Am. Second. Educ. 2013, 41, 50–61. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Y.; Kim, U. Interpersonal relationship and delinquent behavior among adolescents: With specific focus on parent-child relationship, teacher-student relationship, and relationship with friends. Korean J. Psychol. Soc. Issues 2004, 10, 87–115. [Google Scholar]

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Happiness of Middle School Third-Year Students | 1 | ||||||

| 2. Teacher Relationships in High School Freshman year | 0.1979 *** | 1 | |||||

| 3. Depression in High School Freshman year | −0.3166 *** | −0.1986 *** | 1 | ||||

| 4. Peer Relationship in High School Freshman year (Positive) | 0.1738 *** | 0.3446 *** | −0.2594 *** | 1 | |||

| 5. Peer Relationship in High School Freshman year (Negative) | −0.1418 *** | −0.1538 *** | 0.4227 *** | −0.2778 *** | 1 | ||

| 6. Parental Attitude in High School Freshman year (Positive) | 0.2826 *** | 0.4592 *** | −0.3345 *** | 0.3877 *** | −0.2657 *** | 1 | |

| 7. Parental Attitude in High School Freshman year (Negative) | −0.2302 *** | −0.1885 *** | 0.4125 *** | −0.1797 *** | 0.4502 *** | −0.4462 *** | 1 |

| Mean (M) | 3.0509 | 2.7418 | 1.7846 | 3.0682 | 1.7918 | 3.1171 | 1.9634 |

| Standard Deviation (SD) | 0.4583 | 0.4534 | 0.5550 | 0.4726 | 0.8745 | 0.453 | 0.490 |

| Skewness | −0.1214 | −0.2689 | 0.4404 | −0.1779 | 0.5207 | −0.2746 | 0.3510 |

| Kurtosis | 1.0255 | 1.1595 | −0.1982 | 0.6423 | 0.2201 | 0.6755 | 0.2432 |

| Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) | 1.1683 | 1.3306 | 1.4337 | 1.2941 | 1.4180 | 1.6675 | 1.5466 |

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | β | SE | t | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teacher Relationship in High School Freshman year | Constant | 2.1453 | 0.0987 | 24.4646 *** | 2.2217 | 2.6089 |

| Happiness of Middle School Third-Year Student | 0.1470 | 0.0249 | 5.9149 *** | 0.0983 | 0.1957 | |

| Depression in High School Freshman year | Constant | 1.7481 | 0.1220 | 14.3227 *** | 1.5087 | 1.9874 |

| Happiness of Middle School Third-Year Student | −0.0849 | 0.0274 | −3.1019 *** | −0.1387 | −0.0312 | |

| Teacher Relationship in High School Freshman year | −0.1394 | 0.0236 | −5.9050 *** | −0.1857 | −0.0931 |

| Path | β | Standard Error (SE) | 95% Confidence Interval (CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLCI | ULCI | |||

| Total Effect | −0.1054 | 0.0274 | −0.1591 | −0.0517 |

| Direct Effect | −0.0849 | 0.0274 | −0.1387 | −0.0312 |

| Total Indirect Effect | −0.0205 | 0.0053 | −0.0322 | −0.0110 |

| Moderating Variable | Variable | β | SE | t | p | 95% Confidence Interval (CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLCI | ULCI | ||||||

| Peer Relationship in High School Freshman Year (Positive) | Constant | 2.7407 | 0.0092 | 297.6522 | 0.0000 | 2.7226 | 2.7587 |

| Happiness of Middle School Third-Year Students | 0.1404 | 0.0201 | 6.9714 | 0.0000 | 0.1009 | 0.1800 | |

| Peer Relationship in High School Freshman Year (Positive) | 0.3064 | 0.0195 | 15.6798 | 0.0000 | 0.2681 | 0.3447 | |

| Interaction | 0.0296 | 0.0393 | 0.7519 | 0.4522 | −0.0475 | 0.1067 | |

| Increase in R2 due to Interaction | R2 | F | p | ||||

| 0.0002 | 0.5654 | 0.4522 | |||||

| Peer Relationship in High School Freshman Year (Negative) | Constant | 2.7393 | 0.0096 | 285.0916 | 0.0000 | 2.7205 | 2.7581 |

| Happiness of Middle School Third-Year Students | 0.1754 | 0.0210 | 8.3493 | 0.0000 | 0.1342 | 0.2166 | |

| Peer Relationship in High School Freshman Year (Negative) | −0.0996 | 0.0167 | −5.9475 | 0.0000 | −0.1325 | −0.0668 | |

| Interaction | −0.0660 | 0.0367 | −1.7951 | 0.0728 | −0.1380 | 0.0061 | |

| Increase in R2 due to Interaction | R2 | F | p | ||||

| 0.0014 | 3.2224 | 0.0728 | |||||

| Parental Attitude in High School Freshman Year (Positive) | Constant | 2.7432 | 0.0090 | 305.9132 | 0.0000 | 2.7256 | 2.7608 |

| Happiness of Middle School Third-Year Students | 0.0749 | 0.0199 | 3.7632 | 0.0002 | 0.0359 | 0.1139 | |

| Parental Attitude in High School Freshman Year (Positive) | 0.4387 | 0.0199 | 21.9901 | 0.0000 | 0.3995 | 0.4778 | |

| Interaction | −0.0239 | 0.0390 | −0.6121 | 0.5405 | −0.1004 | 0.0527 | |

| Increase in R2 due to Interaction | R2 | F | p | ||||

| 0.0001 | 0.3747 | 0.5405 | |||||

| Parental Attitude in High School Freshman Year (Negative) | Constant | 2.7364 | 0.0097 | 282.0791 | 0.0000 | 2.7173 | 2.7554 |

| Happiness of Middle School Third-Year Students | 0.1567 | 0.0213 | 7.3443 | 0.0000 | 0.1148 | 0.1985 | |

| Parental Attitude in High School Freshman Year (Negative) | −0.1389 | 0.0198 | −6.9998 | 0.0000 | −0.1778 | −0.1000 | |

| Interaction | −0.1045 | 0.0402 | −2.5993 | 0.0094 | −0.1833 | −0.0257 | |

| Increase in R2 due to Interaction | R2 | F | p | ||||

| 0.0030 | 6.7564 | 0.0094 ** | |||||

| Baseline | Effect | Standard Error (SE) | 95% Confidence Interval (CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLCI | ULCI | ||||

| Parental Attitude (Negative) | −1SD (−0.4910) | −0.0360 | 0.0078 | −0.0522 | −0.0218 |

| M (0) | −0.0271 | 0.0058 | −0.0394 | −0.0164 | |

| +1SD (0.4910) | −0.0182 | 0.0063 | −0.0313 | −0.0068 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jeong, S.; Lim, S.-I. The Relationship Between Korean Adolescents’ Happiness and Depression: The Mediating Effect of Teacher Relationships and Moderated Mediation of Peer and Parental Relationships and Parental Attitudes. Healthcare 2025, 13, 730. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070730

Jeong S, Lim S-I. The Relationship Between Korean Adolescents’ Happiness and Depression: The Mediating Effect of Teacher Relationships and Moderated Mediation of Peer and Parental Relationships and Parental Attitudes. Healthcare. 2025; 13(7):730. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070730

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeong, Sookyung, and Shin-Il Lim. 2025. "The Relationship Between Korean Adolescents’ Happiness and Depression: The Mediating Effect of Teacher Relationships and Moderated Mediation of Peer and Parental Relationships and Parental Attitudes" Healthcare 13, no. 7: 730. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070730

APA StyleJeong, S., & Lim, S.-I. (2025). The Relationship Between Korean Adolescents’ Happiness and Depression: The Mediating Effect of Teacher Relationships and Moderated Mediation of Peer and Parental Relationships and Parental Attitudes. Healthcare, 13(7), 730. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070730