A Critical Advantage of Hypnobirthing to Ameliorate Antenatal Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Question

| P | Population | Pregnant women |

| I | Intervention | Hypnobirthing or hypnosis for birth |

| C | Comparison | Usual care |

| O | Outcome | Depression |

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Protocol Registration

2.4. Sources and Search Strategy

2.5. Study Selection

2.6. Procedures for Data Extraction, Appraisal, Analysis, and Synthesis

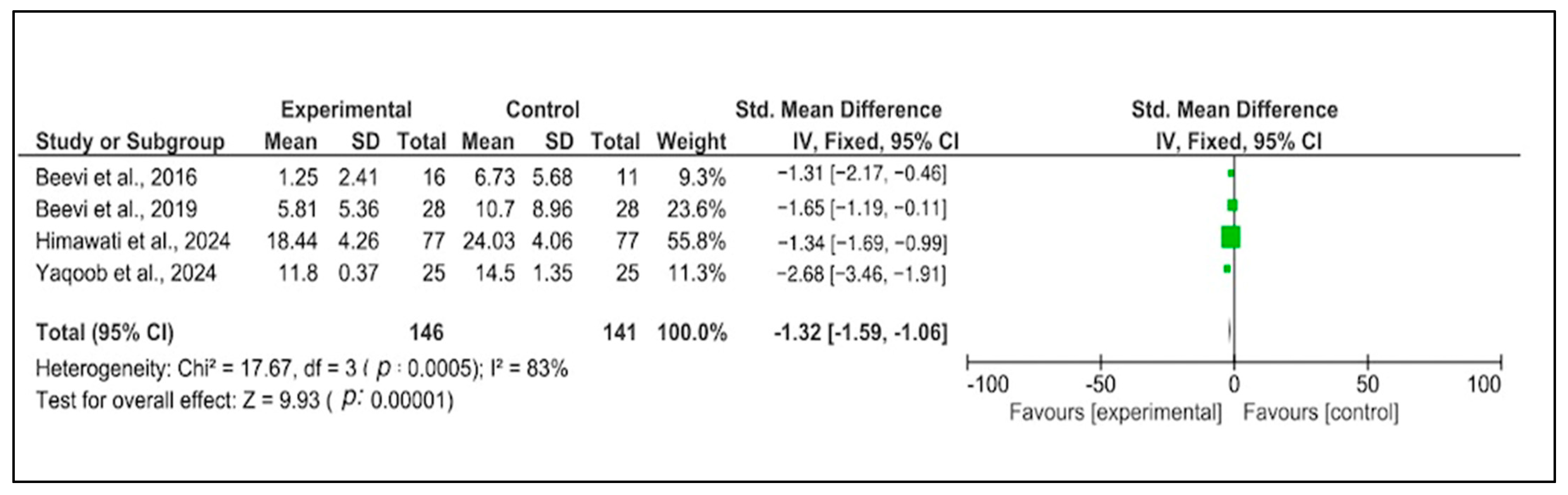

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Included Studies

| No. | Authors, Year | Study Design | Participants | Country | Main Study Description | JBI Scores |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Beevi et al., 2019 [22] | Quasi-experimental design | Pregnant women N = 28 (Experimental group) N = 28 (Control group) | Malaysia |

| 9/9 |

| 2. | Beevi et al., 2016 [21] | Quasi-experimental design | Pregnant women in their second trimester N = 28 (Experimental group) N = 28 (Control group) | Malaysia |

| 9/9 |

| 3. | Catsaros and Wendland, 2023 [16] | Systematic review | N = 7 studies | Not specified |

| 10/11 |

| 4. | Himawati et al., 2024 [23] | Randomized control trial | Pregnant women (N = 154) | Indonesia |

| 7/13 |

| 5. | Uldal et al., 2023 [26] | Descriptive phenomenological study | Pregnant women (N = 9) | Norway |

| 10/10 |

| 6. | Uludag et al., 2023 [27] | Phenomenological design | Hypnobirthing stories obtained from four blogs N = 13 | Not specified |

| 8/10 |

| 7. | Yaqoob et al., 2024 [15] | Randomized control trial | Pregnant women N = 25 (Experimental group N = 25 (Control group) | Pakistan |

| 11/13 |

| 8. | Finlayson et al., 2015 [24] | Qualitative interviews | N = 19 16 first-time mothers and 3 birth companions | England |

| 9/10 |

| 9. | Tabib et al., 2024 [25] | Descriptive qualitative study | N = 26 17 women and 9 partners | Scotland |

| 8/10 |

3.2. Outcome Categories of the Included Studies

3.2.1. The Effects of the Therapy

3.2.2. Administration of the Therapy

3.2.3. The Mechanism of the Therapy

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Savory, N.A.; Hannigan, B.; John, R.M.; Sanders, J.; Garay, S.M. Prevalence and Predictors of Poor Mental Health among Pregnant Women in Wales Using a Cross-Sectional Survey. Midwifery 2021, 103, 103103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, A.; Potdar, J. Maternal Mental Health During Pregnancy: A Critical Review. Cureus 2022, 14, e30656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alturaymi, M.A.; Alsupiany, A.; Almadhi, O.F.; Alduraibi, K.M.; Alaqeel, Y.S.; Alsubayyil, M.; Bin Dayel, M.; Binghanim, S.; Aboshaiqah, B.; Allohidan, F. Prevalence and Correlates of Depression among Pregnant Women at King Abdulaziz Medical City: A Tertiary Hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2024, 16, e56180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woody, C.A.; Ferrari, A.J.; Siskind, D.J.; Whiteford, H.A.; Harris, M.G. A Systematic Review and Meta-Regression of the Prevalence and Incidence of Perinatal Depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 219, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Perinatal Mental Health; World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/mental-health-and-substance-use/promotion-prevention/maternal-mental-health (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Ghazanfarpour, M.; Bahrami, F.; Rashidi Fakari, F.; Ashrafinia, F.; Babakhanian, M.; Dordeh, M.; Abdi, F. Prevalence of Anxiety and Depression among Pregnant Women during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Meta-Analysis. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 43, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebel, C.; MacKinnon, A.; Bagshawe, M.; Tomfohr-Madsen, L.; Giesbrecht, G. Elevated Depression and Anxiety Symptoms among Pregnant Individuals during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Wu, J.; Chen, X. Risk Factors of Perinatal Depression in Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulska, J.; Juszczyk, G.; Gawrońska-Grzywacz, M.; Herbet, M. HPA Axis in the Pathomechanism of Depression and Schizophrenia: New Therapeutic Strategies Based on Its Participation. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creutzberg, K.C.; Sanson, A.; Viola, T.W.; Marchisella, F.; Begni, V.; Grassi-Oliveira, R.; Riva, M.A. Long-Lasting Effects of Prenatal Stress on HPA Axis and Inflammation: A Systematic Review and Multilevel Meta-Analysis in Rodent Studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 127, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, N.; Went, T.R.; Sultan, W.; Sapkota, A.; Khurshid, H.; Qureshi, I.A.; Alfonso, M. Untreated Depression during Pregnancy and Its Effect on Pregnancy Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2021, 13, e17251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health Service. Antenatal and Hypnobirthing Classes; National Health Service. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/start-for-life/pregnancy/preparing-for-labour-and-birth/antenatal-and-hypnobirthing-classes/ (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Atis, F.Y.; Rathfisch, G. The Effect of Hypnobirthing Training given in the Antenatal Period on Birth Pain and Fear. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2018, 33, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buran, G.; Aksu, H. Effect of Hypnobirthing Training on Fear, Pain, Satisfaction Related to Birth, and Birth Outcomes: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2022, 31, 918–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaqoob, H.; Ju, X.D.; Jamshaid, S. Hypnobirthing Training for First-Time Mothers: Pain, Anxiety and Postpartum Wellbeing. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2024, 17, 3033–3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catsaros, S.; Wendland, J. Psychological Impact of Hypnosis for Pregnancy and Childbirth: A Systematic Review. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2023, 50, 101713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Gamero, L.; Reinoso-Cobo, A.; Ruiz-González, M.D.; Cortés-Martín, J.; Muñóz Sánchez, I.; Mellado-García, E.; Piqueras-Sola, B. Impact of Hypnotherapy on Fear, Pain, and the Birth Experience: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, F.L.; Oh, I.-S.; Hayes, T.L. Fixed- versus Random-Effects Models in Meta-Analysis: Model Properties and an Empirical Comparison of Differences in Results. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 2009, 62, 97–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring Inconsistency in Meta-Analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beevi, Z.; Low, W.Y.; Hassan, J. Impact of Hypnosis Intervention in Alleviating Psychological and Physical Symptoms During Pregnancy. Am. J. Clin. Hypn. 2016, 58, 368–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beevi, Z.; Low, W.Y.; Hassan, J. The Effectiveness of Hypnosis Intervention in Alleviating Postpartum Psychological Symptoms. Am. J. Clin. Hypn. 2019, 61, 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himawati, Y.; Demartoto, A.; Murti, B. Effectiveness of Childbirth Education and Hypnobirthing Assistance in Improving Labor Outcome. J. Matern. Child Health 2024, 09, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlayson, K.; Downe, S.; Hinder, S.; Carr, H.; Spiby, H.; Whorwell, P. Unexpected Consequences: Women’s Experiences of a Self-Hypnosis Intervention to Help with Pain Relief during Labour. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015, 15, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabib, M.; Humphrey, T.; Forbes-McKay, K. The Influence of Antenatal Relaxation Classes on Perinatal Psychological Wellbeing and Childbirth Experiences: A Qualitative Study. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol 2024, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uldal, T.; Østmoen, M.S.; Dahl, B.; Røseth, I. Women’s Experiences with Hypnobirth—A Qualitative Study. Sex. Reprod. Healthc. 2023, 37, 100890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uludag, E.; Mete, S. Feelings and Experiences of Turkish Women Using Hypnobirthing in Childbirth: A Non-Traumatic Childbirth Experience. Int. J. Caring Sci. 2023, 16, 344–351. [Google Scholar]

- Mongan, M. Hypnobirthing: The Mongan Method; Health Communications, Inc.: Deerfield Beach, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zajkowska, Z.; Gullett, N.; Walsh, A.; Zonca, V.; Pedersen, G.A.; Souza, L.; Kieling, C.; Fisher, H.L.; Kohrt, B.A.; Mondelli, V. Cortisol and Development of Depression in Adolescence and Young Adulthood—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2022, 136, 105625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, Q.; Zhong, X.; Zhang, X.; Pu, W.; Dong, D.; Jiang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Wang, X.; Detre, J.A.; Yao, S.; et al. State-Independent and Dependent Neural Responses to Psychosocial Stress in Current and Remitted Depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 2017, 174, 971–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zisopoulou, T.; Varvogli, L. Stress Management Methods in Children and Adolescents: Past, Present, and Future. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2023, 96, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, J.A.; Kelsey, C.M.; Krol, K.M.; Grossmann, T. Maternal Recognition of Positive Emotion Predicts Sensitive Parenting in Infancy. Emotion 2023, 23, 1506–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, J.L.; Garside, R.B.; Labella, M.H.; Klimes-Dougan, B. Parent Socialization of Positive and Negative Emotions: Implications for Emotional Functioning, Life Satisfaction, and Distress. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 3455–3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. Hypnosis. Available online: https://dictionary.apa.org/hypnosis (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- Le, J.; Alhusen, J.; Dreisbach, C. Screening for Partner Postpartum Depression: A Systematic Review. MCN Am. J. Matern. Nurs. 2023, 48, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, N.; Fatima, M.; Ghaffar, S.; Subhani, F.; Waheed, S. To Resuscitate or Not to Resuscitate? The Crossroads of Ethical Decision-Making in Resuscitation in the Emergency Department. Clin. Exp. Emerg. Med. 2023, 10, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No. | Summary |

|---|---|

| 1. | The therapy was provided in two to four sessions during pregnancy. |

| 2. | The earliest therapy was provided at week 16 and continued until birth. |

| 3. | Along with the main hypnosis-based techniques, the therapy sessions also include relaxation, ego strengthening, breathing techniques, writing positive affirmations, and childbirth education. |

| 4. | Apart from the official training session with the trainer, the participants were encouraged to do self-practice at home. |

| 5. | Self-practice was performed every day for 25 min or two times a week for 3 h. |

| 6. | To engage participants for self-practice, participants were followed up with a personal home visit, phone call, or text message. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Betriana, F.; Sunarno, S.; Nurwidyaningtyas, W.; Ganefianty, A. A Critical Advantage of Hypnobirthing to Ameliorate Antenatal Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2025, 13, 705. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070705

Betriana F, Sunarno S, Nurwidyaningtyas W, Ganefianty A. A Critical Advantage of Hypnobirthing to Ameliorate Antenatal Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare. 2025; 13(7):705. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070705

Chicago/Turabian StyleBetriana, Feni, Sunarno Sunarno, Wiwit Nurwidyaningtyas, and Amelia Ganefianty. 2025. "A Critical Advantage of Hypnobirthing to Ameliorate Antenatal Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Healthcare 13, no. 7: 705. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070705

APA StyleBetriana, F., Sunarno, S., Nurwidyaningtyas, W., & Ganefianty, A. (2025). A Critical Advantage of Hypnobirthing to Ameliorate Antenatal Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare, 13(7), 705. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070705