1. Introduction

Oral health is an essential aspect of general health and well-being. It involves the state of the mouth, teeth, and orofacial structures. It facilitates individuals to perform essential functions like eating, breathing, and speaking, influencing psychosocial dimensions like self-confidence, social participation, and interactions, and the ability to work without discomfort or embarrassment [

1]. The oral cavity is the primary pathway for entering food into the body. Therefore, oral diseases can damage the oral cavity and potentially other body parts [

2].

Oral diseases are a significant global health burden, with over 3.5 billion people globally affected by oral diseases [

3]. Despite being largely preventable, it causes pain, discomfort, disfigurement, and even death throughout individuals’ lifetimes [

4]. Poor oral health and hygiene can cause non-communicable diseases, increase morbidity, decrease health-related quality of life (HRQoL), and incur higher medical and healthcare expenditures [

5]: a total of USD 380 billion is spent on treating oral diseases, according to a WHO 2019 report [

3]. Additionally, according to this report, three out of four people affected are from low and middle-income countries, indicating oral health inequality, a subject neglected in health policy discussions. This can have profound implications for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly Goal 3, which aims to ensure good health and promote well-being for all ages [

6,

7]. Although SDG 3 aims to achieve good health and well-being, it does not explicitly mention any disease or healthcare system that may have implications for global health strategies [

7,

8]. Research shows an increased focus on this otherwise obscure public health arena, with studies being reported from different locations across the globe, such as Croatia and Mexico [

9,

10,

11]. Abodunrin et al. 2023 opined that current research in the domain of oral health and hygiene aids compliance with other key SDGs along with SDG 3, such as SDG 1 (no poverty), SDG 4 (quality education), SDG 5 (gender equality), and SDG 13 (climate action) [

8,

12,

13].

Oral diseases that affect various age groups are dental caries, periodontal disease, oral cancer, oro-dental trauma, noma, and birth defects like a cleft lip and palate, along with other developmental problems such as malocclusion. Dental caries or tooth decay is a significant concern and is most prevalent along with periodontal diseases, as well as oral cancers [

14]. It is the most widespread oral disease among children and adolescents [

15,

16]. In India, 43.3% of untreated caries of deciduous teeth are prevalent in children of the one to nine age group, and 28.8% of untreated caries of permanent teeth in people above five years [

17]. Another oral disease, gingivitis, is caused by the accumulation of dental biofilm and is a site-specific inflammatory condition that, if untreated, may progress to periodontitis [

18]. Oral conditions are significantly higher in marginalized and vulnerable populations [

19]. These diseases are largely preventable through effective oral hygiene practices and regular dental care. A significant public health concern worldwide is the growing incidences of oral cancer, particularly in communities with widespread tobacco usage, leading to an increased hospital burden and negatively affecting the survival rate [

20].

Oral hygiene practices are important for good oral health. However, most people neglect oral hygiene. The use of toothpicks in place of dental floss is a common practice. Most people do not brush their teeth twice or rinse their mouths after each meal [

5]. Brushing teeth at least once or preferably twice a day, along with flossing and regular visits to the dentist, is essential for good oral health [

21,

22]. Furthermore, good oral health practices should start early so that they become a part of long-term oral health and hygiene [

23]. Understanding oral health also involves understanding the risk factors associated with it. Genetic predisposition, developmental problems, poor oral hygiene, traumatic accidents, along with modifiable risk factors such as tobacco use, alcohol consumption, stress, high sugar intake, and an unhealthy diet, which overlap with many non-communicable diseases [

24], result in oral health diseases. Oral diseases also affect the ability to eat, affecting the nutritional status, and vice versa [

15].

Despite advancements in dental technology and a better understanding of oral diseases, significant disparities in dental health and access to care persist across various demographics. These disparities are influenced by income, race or ethnicity, geographic location, and education. Implementing good oral health and hygiene policies involves understanding the desired population’s knowledge, behavior, attitudes, and practices. There is sufficient literature on oral health from various parts of the country [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29], but, to the best of our knowledge, there are very few articles from Jammu and Kashmir [

30,

31,

32] and none from the Baramulla district. Baramulla is the fourth most populous town in Jammu and Kashmir, with a population of 1,008,039 residents (Census of India, 2011) of which 53.03% are males and 46.95% are females. It is known for its geographical significance and historical legacy [

33,

34]. It is a remote area in the northwest direction located on the banks of the Jhelum River. It is an Aspirational District, 1 of the 112 districts from the entire country, chosen by the Government of India under the Aspirational Districts Program to quickly transform the most under-developed districts of the country through cooperative and competitive federalism by focusing on five socio-economic themes such as health and nutrition, education, agriculture and water resources, financial inclusion, and skill development [

35]. In recent years, it has seen improvements in infrastructure, including enhanced road networks and the establishment of new educational institutions that aim to improve the quality of life for its residents [

36]. A systematic literature search with keywords, (“oral health” OR “oral hygiene” OR “oral hygiene practices” OR “oral hygiene behavior”) AND (“knowledge”) AND (“attitude”) and (“practices”) showed few research articles from the Kashmir region and none from Baramulla. According to the Dental Council of India, Jammu and Kashmir report, more than 85% of the children and 95–100% of the adult population of Jammu and Kashmir suffer from periodontal diseases [

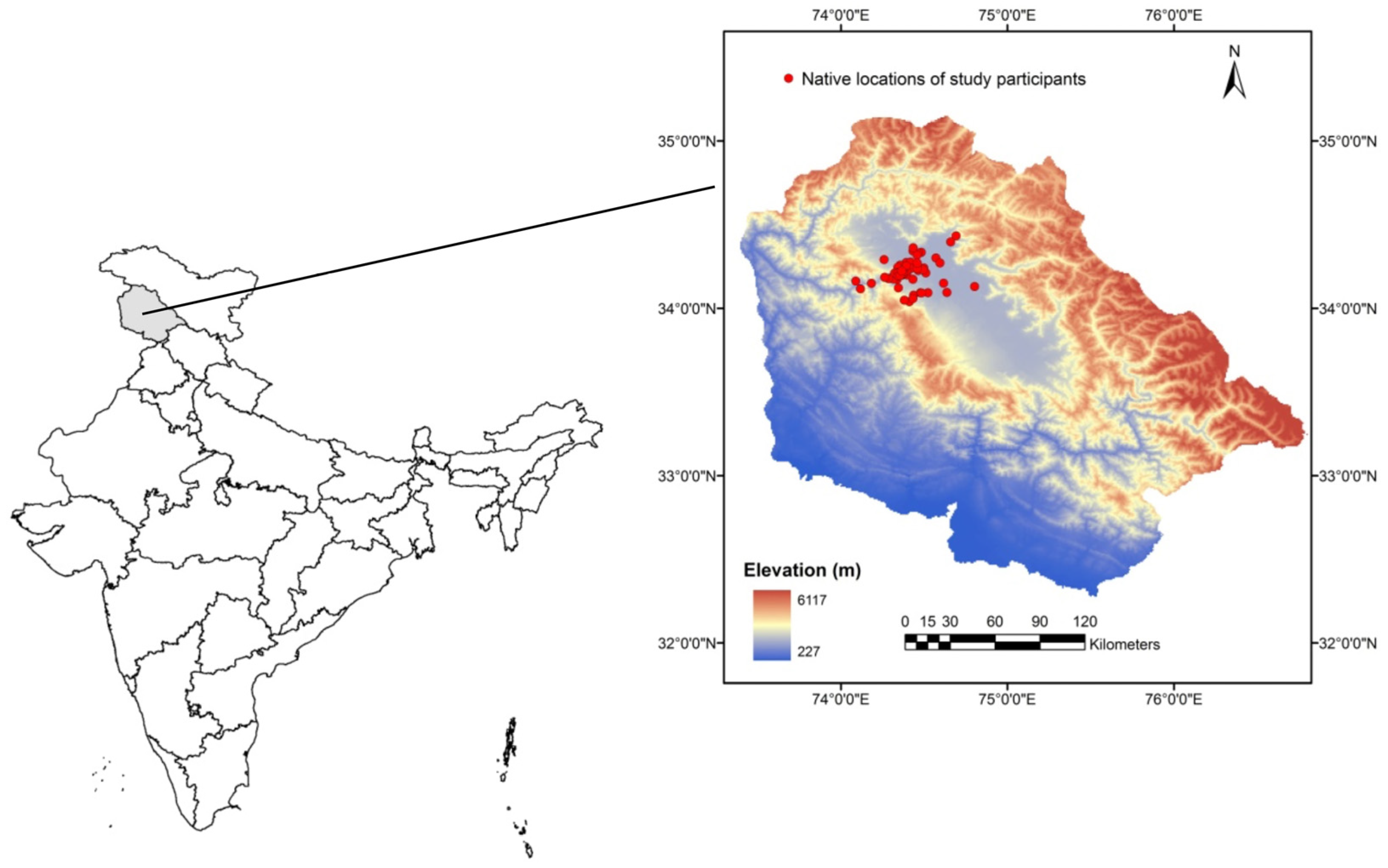

37], and there is a dire necessity for policies and manpower development. Even though Baramulla has a tertiary hospital and the availability of healthcare services, a lack of real-time data on oral and dental status is required for the strategic planning of improving oral healthcare services. This study was conducted to fill the literature gap regarding Baramulla’s oral health status and to understand the practices regarding the oral health and hygiene of its residents. This study can be used as a baseline for understanding the oral health and hygiene of people from varied socio-economic backgrounds in the Baramulla district. This kind of study can be useful for identifying risk factors leading to oral diseases and to help in strategizing oral care prevention through policy interventions.

3. Results

Socio-demographic characteristics: A total of 488 residents of Baramulla participated in the study. Of the total participants, 46.93% (229) were male and 53. 07% (259) were females. The youngest respondent was 4 years old, and the oldest was 80. We categorized them into the following age brackets: 1–10 years, 11–20, 21–30, 31–40, 41–50, 51–60, and above 60 years old. Most of our respondents were young individuals. We had 146 of the total 488, i.e., 29.92%, from the age bracket of 21–30 years, followed by 21.72% of participants from the 31–40 age group and 16.80% of 11–20 years. We had very few participants above 51 years of age: 3.89% in the 51–60 age group and 2.66% above the 61 years of age bracket (see

Table 1) as they were reluctant to participate in the survey. The Baramulla district has 10 medical blocks. The residences of the study participants were also divided into the 10 Medical Blocks and presented in

Supplementary Table S1. We had fair participation from both males and females in our study (

Table 2), except in the age group of 51–60 years, where we had 84.21% male participation and around 15.79% female participation.

Of the people interviewed, 41.39% belonged to the BPL category, 42.62% belonged to the APL, and 15.98% belonged to the PHH and AAY category, indicating that we had participation from different socio-economic strata (socio-economic status,

Table 1 and

Supplementary Table S2). Most of our respondents had attained basic education, and only 8.81% were non-literate (

Supplementary Table S3a,b).

3.1. Oral Hygiene Behaviour

The results show that most respondents brushed their teeth once a day. The chi-square test revealed that there was a significant association of tooth brushing frequency across age

p < 0.001,

Table 3a) and gender (

p = 0.02,

Table 3b). The highest percentage of the respondents in each age group brushed their teeth once a day (

Table 3a). In younger age groups, i.e., 11–20, 21–30, and 31–40, the second highest percentage of the residents brushed their teeth twice daily (26.83% in the 11–20 age bracket, 27.08% in the 21–30 age bracket, and 20.75% in the 31–40 age bracket). In the higher age group, a larger proportion of residents either brushed their teeth alternately or seldom or never (

Table 3a). 64.98% of females brushed their teeth once, compared to 58.87% of males. Additionally, 11.69% of males brushed their teeth rarely, as opposed to only 4.98% of female respondents (

Table 3b). Most of the respondents across age groups and genders brushed their teeth in the morning as opposed to brushing their teeth at night (

Table 4a,b). The chi-square test revealed an association of age

p < 0.001) but not of gender (

p = 0.25) on the timing of tooth-brushing. There was a decrease in the proportion of respondents brushing their teeth with increasing age (see

Table 4b). All the respondents reported using toothbrushes and toothpaste as oral hygiene aids.

The residents of Baramulla showed a very poor frequency of cleaning their tongues. Over 60% of respondents in each age group did not clean their tongues, and only 30% or less cleaned their tongues daily (

Table 5a,b). There was an association of age but not of gender on the tongue cleaning behavior (

p < 0.001;

p = 0.16, respectively, chi-square test). The younger age brackets of 1–10 and 11–20 had the highest proportion of individuals not cleaning their tongue (95.16% and 82.93%, respectively), with a slight improvement in tongue-cleaning habits in higher age groups (see

Table 5a). There was an association of age but not of gender in the usage of mouthwash or other cleaning aids (

p < 0.001;

p = 0.211, respectively, chi-square test,

Table 6a,b). More than 60% of people across age groups did not use mouthwash or any other oral aid to keep their mouth clean (

Table 6a,b). The use of mouthwash and any other cleaning aid declined with age, with more than 80% of people above 50 years not using any aid to keep their mouth clean except in age group 1–10, where the percentage was above 90% (

Table 6a).

3.2. Dental Visits

All the people above 61 years of age and more than 85% of people above the age of 21 had visited the dentist at least once (

Table 7a). Most of the people primarily visited if they felt pain, sensitivity, or discomfort in their teeth. The chi-square analysis revealed an association of age (

p = 0.02) but not of gender (

p = 0.96) in the frequency of dental visits (

Table 7a,b). Apart from this, many respondents had additional oral/dental issues for which they visited the doctor, such as filling, root canal therapy (RCT), tooth extraction or multiple teeth extraction, medication, ortho, scaling, splinting, and yellow teeth (

Table 7c).

3.3. Oral Health-Related Dietary Behaviour

The chi-square analysis revealed an association with age (

p < 0.001) but not with gender (

p = 0.17) in the frequency of eating fast food (

Table 8a,b). The highest proportion of the young respondents (43.55% in 1–10, 43.90% in 11–20, and 34.25% in 21–30 age bracket) had fast food daily, whereas the highest proportion of oldest participants, i.e., above 60 years of age, rarely had fast food (see

Table 8a).

3.4. Tobacco Consumption

More than 70% of people across all age groups did not report consuming tobacco. Most of the respondents who did consume tobacco did not reveal how many cigarettes they had in a day or for how long they had been using tobacco or cigarettes. Use of tobacco had an association with age (

p < 0.001; chi-square test,

Table 9a). The percentage of respondents who reported consuming tobacco increased with increasing age brackets (see

Table 9a). There was no association of gender t

p = 0.28; chi-square test,

Table 9b).

3.5. Self-Rating of Overall Oral Health

Very few participants reported excellent or very good oral health. Chi-square analysis showed an association of gender (

p < 0.001) but not of age (

p = 0.19) on the self-reported overall oral health (

Table 10a,b). The majority of male respondents (45.88%) reported fair oral health, whereas the majority of female respondents (35.29%) reported poor overall oral health (

Table 10b).

4. Discussion

This study aimed to examine the oral health and hygiene practices of the people of the Baramulla district in the Indian Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir. This is the first account of the oral hygiene practices from the Baramulla district, a gateway to the Kashmir Valley. Between the Pir Pranjal Mountain range in the northwest and the fertile plains of the Indus and Ganges in the south, Baramulla is fast catching up with health, education, and infrastructure development [

36,

41]. Such baseline studies are important for identifying risk groups and risk factors leading to oral diseases and to help strategize oral care prevention through policy interventions.

Cleaning teeth is an essential part of oral hygiene practice. It is an established method of removing dental plaque, stains, and food deposits from the teeth, thereby preventing dental caries and periodontal diseases [

15]. Our study shows that the highest proportion of the residents in each age group brushed their teeth only once. It does not meet the oral recommendation of brushing the teeth twice daily [

42,

43]. Studies on tooth brushing frequency within the Indian population reveal similar trends. A study from Kancheepuram District, Tamil Nadu, reported that 56% of the urban population brushed once daily, while 44% brushed twice daily, whereas 86% of the rural population brushed once daily, and only 13% brushed twice daily [

44]. A study focusing on oral health awareness in Chennai found that 37.62% of participants brushed twice daily, while the remaining participants brushed only once a day [

45]. A recent report indicates that approximately 45% of Indians brush their teeth twice daily, which is notably lower than several countries [

46]. For example, the prevalence of twice-a-day tooth brushing is seen in a higher proportion of the cohorts studied: 51% in the Australian, 75% in the English and 85% in the Swedish population [

47,

48,

49]. Interestingly, in the younger cohort (from 11–40 years), the second highest proportion of people brushed their teeth twice. This indicates that the young population is possibly aware of good oral practices due to the oral health education programs being implemented in new education policies and greater awareness and heightened body image in the new digital era. These data are important in affirming the role of implementing oral education at school levels. Young children develop reflexes toward general hygiene practices and overall attitude toward health early in childhood [

22]. Therefore, oral health education should be integral to the school curriculum. Data from countries like Australia and New Zealand, which have excellent oral health education programs, show decreased dental caries among school children [

22]. Our study shows a higher proportion of elderly people either brushed their teeth alternately or never. This is similar to studies that show older populations with poor oral hygiene and health indicating oral frailty [

50,

51,

52]. The study on 45–74-year-old men from Northeast Poland found that only 53.2% of respondents brushed their teeth once a day and only 21% used additional measures to maintain oral hygiene [

50]. We found a relatively higher number of males rarely or seldom brushing their teeth as compared to females. A similar study from Japan showed that the rate of good oral behavior, including tooth brushing, was significantly higher among females than among males [

53].

Cleaning of the tongue enhances oral hygiene [

54]. However, our study population of Baramulla showed poor tongue-cleaning behavior across age groups, similar to previous studies [

55,

56] as well as less usage of mouthwash or any other oral aid to keep their mouth clean. On the contrary, a study conducted at a dental college in Jamnagar found that 67.2% of patients cleaned their tongues, with a higher prevalence among males (68.9%) compared to females (64.8%) [

57]. A dental health survey in Scotland revealed that most of the participants (38.1%) had never used mouthwash, similar to our survey result [

58]. We observed a general reluctance and hesitancy among respondents regarding personal oral hygiene questions. This may be due to unwillingness to seek oral care due to negligence, financial issues, geographic isolation, and time-consuming visit procedures [

59,

60]. The data show that most of the population has made visits to the dental hospital or the dentist, but the primary reasons for visiting have been pain and sensitivity. The common practice that the respondents conveyed was seeking medications with no intention of treatment or removal of the tooth because of financial constraints, dental anxiety, fear, length of procedures, long waiting hours, and more visits. Upon medication, if the pain subsided, most people did not follow up with a dental checkup.

Fast-food consumption patterns varied between the age groups, with the younger population having fast food either daily or several days a week as opposed to older age groups that preferred not to consume fast food. This is similar to reports indicating age as an important determinant in dietary choices [

61]. Consumption of fast food negatively affects oral health [

62]. The oral health of adolescents and young people is usually bad since they have poor dietary choices and an overconsumption of sugary drinks, snacks, and fast foods. They also tend to disregard their guardian’s advice and may not be inclined towards good hygiene [

15].

Our study reported low consumption of tobacco. Collecting data on tobacco usage is challenging owing to the sensitive personal, informal, and social stigma associated with it. The majority of male respondents reported fair oral health as opposed to females who reported poor oral health. This is contrary to several other studies where women tend to report a higher perception of their oral health status than men. They also viewed their oral health positively, prioritized oral health care, and took great interest in personal appearance [

63,

64,

65]. However, some reports indicate that women have a lower self-assessment of oral health [

66]. This might be because of lower self-esteem in women due to societal, psychological, or economic factors [

67].

The study should be treated as baseline data for investigating the oral health and hygiene behavior of the Baramulla district. The study has several limitations that we would like to address in the future. This study could not establish the knowledge and attitude of the people towards oral health. The socio-economic and educational levels impacting oral health were not examined. Furthermore, a longitudinal study tracking changes in practices concerning oral health after imparting knowledge regarding oral health would be recommended. The cause-and-effect relationship between oral hygiene practices and oral health is warranted. The present study should have ideally included a pilot study with 15–20 respondents as per the WHO recommendations, and the responses should have been validated with standard statistical measures such as Cronbach’s alpha. Additionally, an objective assessment of oral health by expert medical practitioners, along with self-reported overall oral health, would have given more confidence to the dataset.