What Nurses’ Work–Life Balance in a Clinical Environment Would Be

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

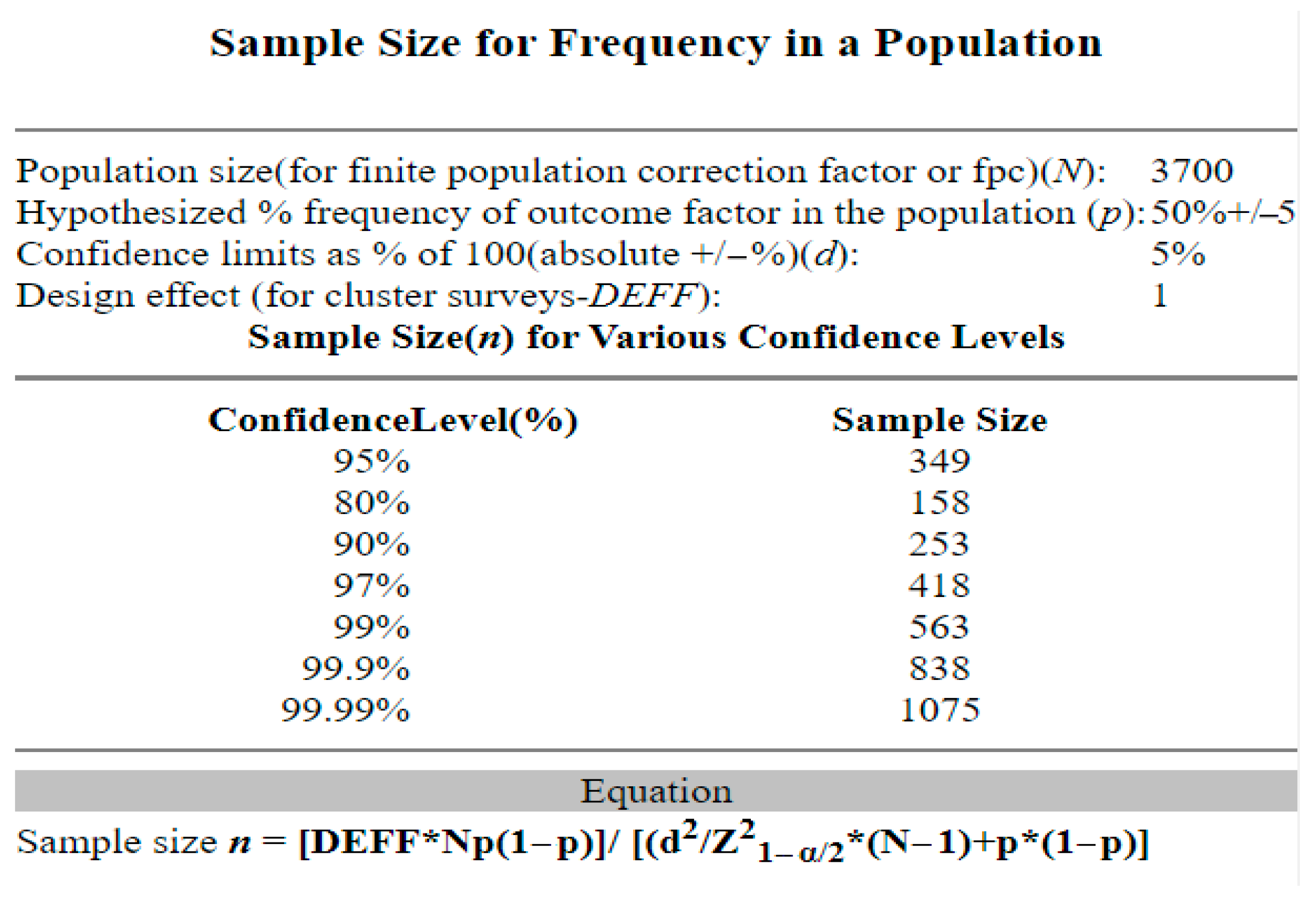

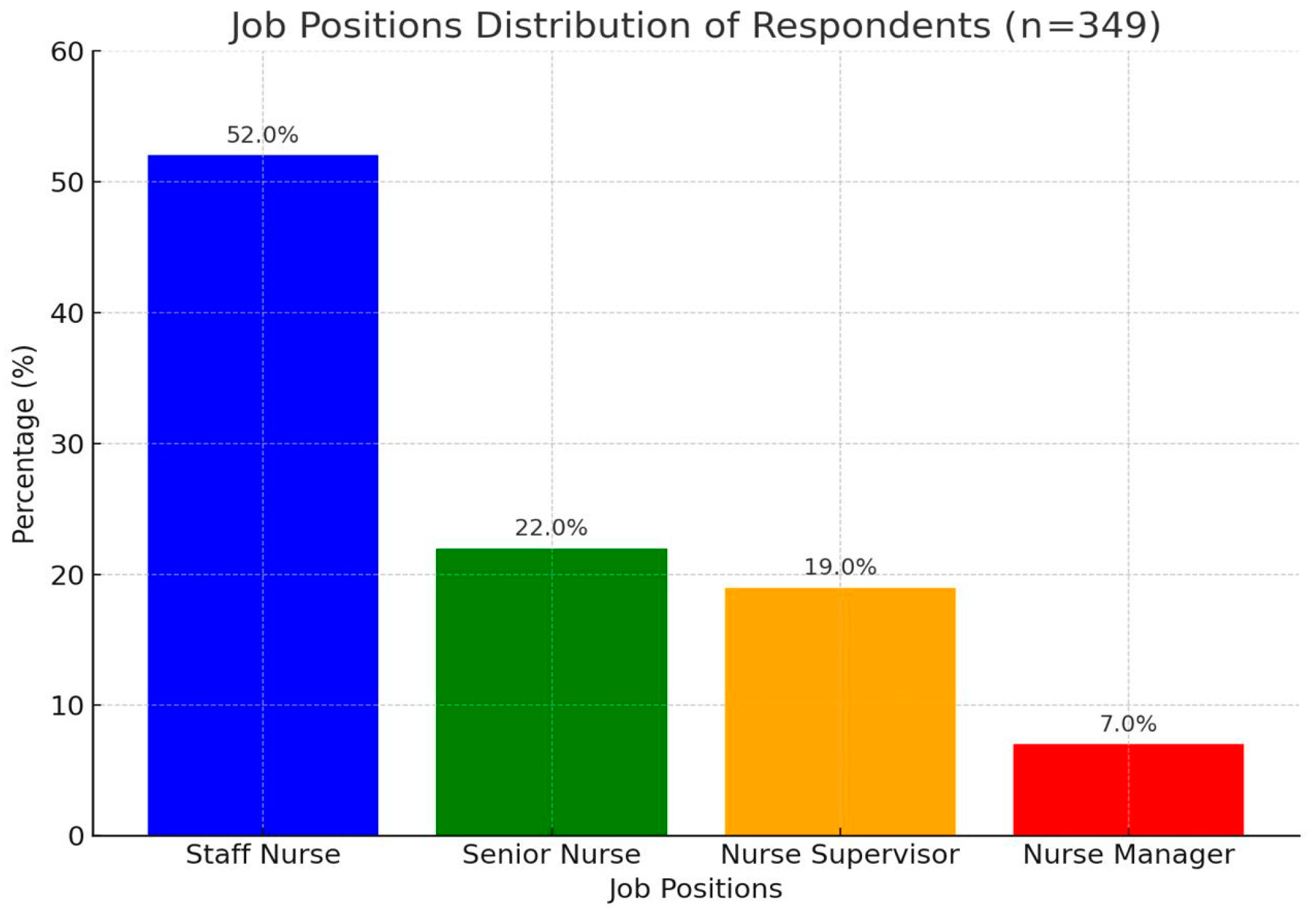

2.1. Sample and Settings

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

Reliability Analysis

4. Discussion

Avenues for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Implication of Research Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. The Study Questionnaire

| Part 1: Sociodemographic Profile |

|---|

| Which category below includes your age? |

| 24 > 29 years old |

| 30 > 35 years old |

| 36 > 41 years old |

| 42 > 47 years old |

| 48 or more |

| Gender |

| Female |

| Male |

| Social Status |

| Single |

| Married |

| Divorced |

| Widower |

| Your educational level |

| Diploma degree |

| Bachelor’s degree |

| Master’s degree |

| PhD |

| Part 2: Work Characteristics |

|---|

| Which of the following is your department/workplace? |

| Paediatric ward |

| Gynaecology ward |

| Medical and surgical ward |

| Outpatient clinic |

| Other |

| Years of experience |

| 1 > 6 years |

| 7 > 12 years |

| 13 > 18 years |

| 19 or more |

| Salary: |

| Less than 5000 SR |

| 5000 to 10,000 SR |

| More than 10,000 SR |

| Current position |

| Staff nurse |

| Nurse supervisor |

| Head nurse |

| Nurse manager |

| Items | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I have a clear set of goals and aims to enable me to do my job | |||||

| 2. I feel able to voice opinions and influence changes in my area of work | |||||

| 3. I have the opportunity to use my abilities at work | |||||

| 4. I feel well at the moment | |||||

| 5. My employer provides adequate facilities and flexibility for me to fit work in around my family life | |||||

| 6. My current working hours/patterns suit my personal circumstances | |||||

| 7. I often feel under pressure at work | |||||

| 8. When I have done a good job, it is acknowledged by my line manager | |||||

| 9. Recently, I have been feeling unhappy and depressed | |||||

| 10. I am satisfied with my life | |||||

| 11. I am encouraged to develop new skills | |||||

| 12. I am involved in decisions that affect me in my own area of work | |||||

| 13. My employer provides me with what I need to do my job effectively | |||||

| 14. My line manager actively promotes flexible working hours/patterns | |||||

| 15. In most ways, my life is close to ideal | |||||

| 16. I work in a safe environment | |||||

| 17. Generally things work out well for me | |||||

| 18. I am satisfied with the career opportunities available for me here | |||||

| 19. I often feel excessive levels of stress at work | |||||

| 20. I am satisfied with the training I receive in order to perform my present job | |||||

| 21. Recently, I have been feeling reasonably happy, all things considered | |||||

| 22. The working conditions are satisfactory | |||||

| 23. I am involved in decisions that affect members of the public in my own | |||||

| 24. I am satisfied with the overall quality of my working life |

| Items | Almost Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Often | Very Often | Always |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. At my work, I feel bursting with energy | ||||||

| 2. I find the work that I do full of meaning and purpose | ||||||

| 3. Time flies when I’m working | ||||||

| 4. At my job, I feel strong and vigorous | ||||||

| 5. I am enthusiastic about my job | ||||||

| 6. When I am working, I forget everything else around me | ||||||

| 7. My job inspires me | ||||||

| 8. When I get up in the morning, I feel like going to work | ||||||

| 9. I feel happy when I am working intensely | ||||||

| 10. I am proud on the work that I do | ||||||

| 11. I am immersed in my work | ||||||

| 12. I can continue working for very long periods at a time | ||||||

| 13. To me, my job is challenging | ||||||

| 14. I get carried away when I’m working | ||||||

| 15. At my job, I am very resilient mentally | ||||||

| 16. It is difficult to detach myself from my job | ||||||

| 17. At my work, I always persevere, even when things do not go well |

References

- Afsar, B.; Rehman, Z.U. Relationship between work-family conflict, job embeddedness, workplace flexibility, and turnover intentions. Makara Hum. Behav. Stud. Asia 2017, 21, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.H.; Sloane, D.M.; Clarke, S.; Poghosyan, L.; Cho, E.; You, L.; Finlayson, M.; Kanai-Pak, M.; Aungsuroch, Y. Importance of work environments on hospital outcomes in nine countries. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2011, 23, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Sabei, S.D.; Labrague, L.J.; Miner Ross, A.; Karkada, S.; Albashayreh, A.; Al Masroori, F.; Al Hashmi, N. Nursing work environment, turnover intention, job burnout, and quality of care: The moderating role of job satisfaction. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2020, 52, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dossary, R.N. The Relationship Between Nurses’ Quality of Work-Life on Organizational Loyalty and Job Performance in Saudi Arabian Hospitals: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 918492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albaalharith, M.; Alanezi, F.; Althumairi, A.; Aljaffary, A.; Alfayez, A.; Alsalman, D.; Alhodaib, H.; AlShammari, M.M.; Aldossary, R.; Alanzi, T.M. Opinions of healthcare leaders on the barriers and challenges of using social media in Saudi Arabian healthcare settings. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2021, 23, 100543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almalki, M.J.; FitzGerald, G.; Clark, M. The relationship between quality of work life and turnover intention of primary health care nurses in Saudi Arabia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Nurses Association. Healthy Work Environment. 2021. Available online: https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/work-environment/health-safety/ (accessed on 23 September 2022).

- Brešan, M.; Erčulj, V.; Lajovic, J.; Ravljen, M.; Sermeus, W.; Grosek, Š. The relationship between the nurses’ work environment and the quality and safe nursing care: Slovenian study using the RN4CAST questionnaire. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0261466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab, G.M.; Elnagar, M. Work Engagement of staff nurses and its Relation to Psychological Work Stress. J. Nurs. Health Sci. 2019, 8, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easton, S.; Van Laar, D. Work-Related Quality of Life (WRQoL) Scale—A Measure of Quality of Working Life, 1st ed.; University of Portsmouth: Portsmouth, UK, 2013; Available online: http://www.qowl.co.uk/docs/WRQoL%20individual%20booklet%20Dec2013.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2022).

- Esaki, N. Trauma-responsive organizational cultures: How safe and supported do employees feel? Hum. Serv. Organ. Manag. Leadersh. Gov. 2020, 44, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fradelos, E.; Papathanasiou, I.; Alikari, V. Assessment of Work-Related Quality of Life Among Nurses in Greece. Int. J. Biomed. Healthc. 2020, 8, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sierra, R.; Fernández-Castro, J.; Martínez-Zaragoza, F. Work engagement in nursing: An integrative review of the literature. J. Nurs. Manag. 2016, 24, E101–E111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzaro, G.; Clari, M.; Donato, F.; Dimonte, V.; Mucci, N.; Easton, S.; Van Laar, D.; Gatti, P.; Pira, E. A contribution to the validation of the Italian version of the work-related quality of life scale. Med. Lav. 2020, 111, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokhale, M. Work-related quality of life and work engagement of college teachers. Annamalai Int. J. Bus. Stud. Res. 2015, 1, 60–63. [Google Scholar]

- Hassona, M.; Albaqawi, H.; Laput, V. Effect of Saudi nurses’ perceived work-life quality on work engagement and organizational commitment. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2021, 8, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegazy, A.M.; Ibrahim, M.M.; Shokry, W.A.; El Shrief, H.A. Work environment factors in nursing practice. Menoufia Nurs. J. 2021, 6, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wang, L.; Dong, X.; Li, B.; Wan, Q. Effects of nursing work environment on work-related outcomes among psychiatric nurses: A mediating model. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 28, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaddourah, B.; Abu-Shaheen, A.K.; Al-Tannir, M. Quality of nursing work life and turnover intention among nurses of tertiary care hospitals in Riyadh: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Nurs. 2018, 17, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N. Factors that Influence Nurses’ Intention to Leave Adult Critical Care Areas: A Mixed-method Sequential Explanatory Study. Ph.D. Thesis, Oxford Brookes University, Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kol, E.; İlaslan, E.; Turkay, M. The effectiveness of strategies similar to the Magnet model to create positive work environments on nurse satisfaction. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2017, 23, e12557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutney-Lee, A.; Wu, E.S.; Sloane, D.M.; Aiken, L.H. Changes in hospital nurse work environments and nurse job outcomes: An analysis of panel data. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2013, 50, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lake, E.T.; Sanders, J.; Duan, R.; Riman, K.A.; Schoenauer, K.M.; Chen, Y. A meta-analysis of the associations between the nurse work environment in hospitals and 4 sets of outcomes. Med. Care 2019, 57, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zheng, J.; Liu, K.; You, L. Relationship between work environments, nurse outcomes, and quality of care in ICUs: Mediating role of nursing care left undone. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2019, 34, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenção, L. Work engagement among participants of residency and professional development programs in nursing. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2018, 71, 1487–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M.D.; Rochman, M.F.; Sloane, D.M.; Berg, R.A.; Mancini, M.E.; Nadkarni, V.M.; Merchant, R.M.; Aiken, L.H.; Investigators, A.H.A.s.G.W.T.G.-R. Better nurse staffing and nurse work environments associated with increased survival of in-hospital cardiac arrest patients. Med. Care 2016, 54, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, A.; Jesus, É. Nursing work environment and patient outcomes in a hospital context: A scoping review. JONA J. Nurs. Adm. 2020, 50, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Min, H.K. Turnover intention in the hospitality industry: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 90, 102599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennbrant, S.; Dåderman, A. Job demands, work engagement and job turnover intentions among registered nurses: Explained by work-family private life inference. Work 2021, 68, 1157–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poku, C.A.; Bayuo, J.; Agyare, V.A.; Sarkodie, N.K.; Bam, V. Work engagement, resilience and turnover intentions among nurses: A mediation analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remegio, W.; Rivera, R.R.; Griffin, M.Q.; Fitzpatrick, J.J. The Professional Quality of Life and Work Engagement of Nurse Leaders. Nurse Lead 2021, 19, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-García, M.C.; Márquez-Hernández, V.V.; Granados-Gámez, G.; Aguilera-Manrique, G.; Gutiérrez-Puertas, L. Magnet hospital attributes in nursing work environment and its relationship to nursing students’ clinical learning environment and satisfaction. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 787–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakai, M.; Naruse, T.; Watai, I.; Arimoto, A.; Murashima, S. A Literature Review on Work Engagement of Nurses. J. Jpn. Acad. Nurs. Sci. 2012, 32, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Salanova, M. Utrecht work engagement scale-9. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2003, 56, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Fu, L.; Yan, C.; Wang, Y.; Fan, L. Quality of work life and work engagement among nurses with standardised training: The mediating role of burnout and career identity. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2022, 58, 103276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tei-Tominaga, M.; Nakanishi, M. Factors related to turnover intentions and work-related injuries and accidents among professional caregivers: A cross-sectional questionnaire study. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2020, 25, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bogaert, P.; Peremans, L.; Van Heusden, D.; Verspuy, M.; Kureckova, V.; Van de Cruys, Z.; Franck, E. Predictors of burnout, work engagement and nurse reported job outcomes and quality of care: A mixed method study. BMC Nurs. 2017, 16, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, H.; Sewell, K.A.; Woody, G.; Rose, M.A. The state of the science of nurse work environments in the United States: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2018, 5, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WorldMedicalAssociation. WMA Declaration of Helsinki—Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. Available online: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/ (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- Yang, Y.; Chen, J. Related factors of turnover intention among pediatric nurses in mainland China: A structural equation modeling analysis. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2020, 53, e217–e223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, H.-Y.; Seo, H.-J.; Cho, Y.; Kim, J. Mediating role of psychological capital in relationship between occupational stress and turnover intention among nurses at veterans administration hospitals in Korea. Asian Nurs. Res. 2017, 11, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubair, M.H.; Hussain, L.R.; Williams, K.N.; Grannan, K.J. Work-related quality of life of US general surgery residents: Is it really so bad? J. Surg. Educ. 2017, 74, e138–e146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sociodemographic Data | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 29 years or less | 85 | 24.4% |

| 30–35 years | 130 | 37.2% | |

| 36–41 years | 72 | 20.6% | |

| 42–47 years | 45 | 12.9% | |

| 48 years or more | 17 | 4.9% | |

| Gender | Female | 221 | 63.3% |

| Male | 128 | 36.7% | |

| Social Status | Single | 102 | 29.2% |

| Married | 199 | 57.0% | |

| Divorced | 38 | 10.9% | |

| Widow | 10 | 2.9% | |

| Educational Level | Diploma degree | 107 | 30.7% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 182 | 52.1% | |

| Master’s degree | 51 | 14.6% | |

| Ph.D. degree | 9 | 2.6% | |

| Work Data | n | % | |

| Workplace/department work | Paediatric ward | 61 | 17.5% |

| Gynaecology ward | 84 | 24.1% | |

| Medical and surgical ward | 78 | 22.3% | |

| Outpatient clinics | 68 | 19.5% | |

| Others | 58 | 16.6% | |

| Years of experience | 6 years or less | 108 | 30.9% |

| 7–12 years | 141 | 40.4% | |

| 13–18 years | 60 | 17.2% | |

| 19 years or more | 40 | 11.5% | |

| Professional income | Less than 5000 SR | 48 | 13.8% |

| 5000 to 10,000 SR | 149 | 42.7% | |

| More than 10,000 SR | 152 | 43.6% | |

| Less than 5000 SR | 48 | 13.8% | |

| Work-Related Quality of Life | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree | Mean | SD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| 1 I have clear goals and objectives that help me do my job. | 28 | 8.0% | 109 | 31.2% | 60 | 17.2% | 81 | 23.2% | 71 | 20.3% | 3.17 | 1.29 |

| 2. I feel like I can say what I think and make changes in my work area. | 25 | 7.2% | 98 | 28.1% | 72 | 20.6% | 132 | 37.8% | 22 | 6.3% | 3.08 | 1.09 |

| 3. I get to use my skills at work. | 24 | 6.9% | 105 | 30.1% | 96 | 27.5% | 86 | 24.6% | 38 | 10.9% | 3.03 | 1.12 |

| 4. I’m feeling good right now. | 29 | 8.3% | 94 | 26.9% | 86 | 24.6% | 115 | 33.0% | 25 | 7.2% | 3.04 | 1.10 |

| 5. My employer gives me the tools and freedom I need to balance work with my family life. | 37 | 10.6% | 96 | 27.5% | 83 | 23.8% | 95 | 27.2% | 38 | 10.9% | 3.00 | 1.19 |

| 6. My current work schedule and hours fit my personal needs. | 52 | 14.9% | 93 | 26.6% | 87 | 24.9% | 84 | 24.1% | 33 | 9.5% | 2.87 | 1.21 |

| 7. I often feel pressure at work. | 48 | 13.8% | 93 | 26.6% | 80 | 22.9% | 95 | 27.2% | 33 | 9.5% | 2.92 | 1.21 |

| 8. When I do a good job, my line manager tells me so. | 47 | 13.5% | 87 | 24.9% | 96 | 27.5% | 87 | 24.9% | 32 | 9.2% | 2.91 | 1.18 |

| 9. I’ve been feeling sad and unhappy lately. | 55 | 15.8% | 102 | 29.2% | 77 | 22.1% | 81 | 23.2% | 34 | 9.7% | 2.82 | 1.23 |

| 10. I’m happy with my life. | 40 | 11.5% | 87 | 24.9% | 82 | 23.5% | 103 | 29.5% | 37 | 10.6% | 3.03 | 1.20 |

| 11. I’m encouraged to learn new skills. | 46 | 13.2% | 105 | 30.1% | 87 | 24.9% | 83 | 23.8% | 28 | 8.0% | 2.83 | 1.17 |

| 12. I have a say in decisions that affect me at work. | 41 | 11.7% | 95 | 27.2% | 96 | 27.5% | 92 | 26.4% | 25 | 7.2% | 2.90 | 1.13 |

| 13. My boss gives me everything I need to do my job well. | 38 | 10.9% | 109 | 31.2% | 88 | 25.2% | 86 | 24.6% | 28 | 8.0% | 2.88 | 1.14 |

| 14. My boss actively promotes flexible work hours and schedules. | 45 | 12.9% | 95 | 27.2% | 89 | 25.5% | 96 | 27.5% | 24 | 6.9% | 2.88 | 1.15 |

| 15. My life is pretty good in most ways. | 39 | 11.2% | 99 | 28.4% | 101 | 28.9% | 85 | 24.4% | 25 | 7.2% | 2.88 | 1.12 |

| 16. I work in a safe place. | 42 | 12.0% | 89 | 25.5% | 85 | 24.4% | 101 | 28.9% | 32 | 9.2% | 2.98 | 1.18 |

| 17. Most of the time, things go well for me. | 45 | 12.9% | 87 | 24.9% | 103 | 29.5% | 84 | 24.1% | 30 | 8.6% | 2.91 | 1.16 |

| 18. I’m happy with the job opportunities here. | 44 | 12.6% | 92 | 26.4% | 83 | 23.8% | 97 | 27.8% | 33 | 9.5% | 2.95 | 1.19 |

| 19. I often feel too much stress at work. | 47 | 13.5% | 104 | 29.8% | 87 | 24.9% | 86 | 24.6% | 25 | 7.2% | 2.82 | 1.16 |

| 20. I’m happy with the training I get to do my current job. | 37 | 10.6% | 97 | 27.8% | 93 | 26.6% | 94 | 26.9% | 28 | 8.0% | 2.94 | 1.14 |

| 21. Lately, all things considered, I’ve been feeling pretty good. | 38 | 10.9% | 97 | 27.8% | 100 | 28.7% | 82 | 23.5% | 32 | 9.2% | 2.92 | 1.15 |

| 22. The conditions of work are good. | 44 | 12.6% | 101 | 28.9% | 96 | 27.5% | 92 | 26.4% | 16 | 4.6% | 2.81 | 1.10 |

| 23. I help make decisions that affect the public in my own community. | 43 | 12.3% | 91 | 26.1% | 94 | 26.9% | 98 | 28.1% | 23 | 6.6% | 2.91 | 1.14 |

| 24. I am happy with the overall quality of my work life. | 50 | 14.3% | 87 | 24.9% | 90 | 25.8% | 101 | 28.9% | 21 | 6.0% | 2.87 | 1.16 |

| Total | 984 | 12% | 2312 | 28% | 2111 | 25% | 2236 | 27% | 733 | 9% | 2.932 | 0.919 |

| Work Engagement Scale | Almost Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Often | Very Often | Always | Mean | SD | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| 1. I am overflowing with enthusiasm at work. | 19 | 5.4% | 117 | 33.5% | 61 | 17.5% | 50 | 14.3% | 50 | 14.3% | 52 | 14.9% | 3.43 | 1.56 |

| 2. I find my work to be meaningful and purposeful. | 11 | 3.2% | 103 | 29.5% | 61 | 17.5% | 74 | 21.2% | 76 | 21.8% | 24 | 6.9% | 3.50 | 1.37 |

| 3. Time flies when I’m working. | 12 | 3.4% | 85 | 24.4% | 87 | 24.9% | 85 | 24.4% | 49 | 14.0% | 31 | 8.9% | 3.48 | 1.33 |

| 4. I feel powerful and vigorous at work. | 15 | 4.3% | 86 | 24.6% | 85 | 24.4% | 62 | 17.8% | 73 | 20.9% | 28 | 8.0% | 3.50 | 1.38 |

| 5. I am excited about my job. | 18 | 5.2% | 84 | 24.1% | 80 | 22.9% | 77 | 22.1% | 60 | 17.2% | 30 | 8.6% | 3.48 | 1.38 |

| 6. When I am working, I ignore everything else around me. | 25 | 7.2% | 74 | 21.2% | 80 | 22.9% | 75 | 21.5% | 69 | 19.8% | 26 | 7.4% | 3.48 | 1.40 |

| 7. My job inspires me. | 26 | 7.4% | 77 | 22.1% | 74 | 21.2% | 72 | 20.6% | 63 | 18.1% | 37 | 10.6% | 3.52 | 1.46 |

| 8. When I wake up in the morning, I want to go to work. | 33 | 9.5% | 82 | 23.5% | 62 | 17.8% | 67 | 19.2% | 81 | 23.2% | 24 | 6.9% | 3.44 | 1.47 |

| 9. I am pleased when I am working intensely. | 29 | 8.3% | 79 | 22.6% | 74 | 21.2% | 90 | 25.8% | 51 | 14.6% | 26 | 7.4% | 3.38 | 1.39 |

| 10. I am proud of the work that I do. | 28 | 8.0% | 67 | 19.2% | 61 | 17.5% | 73 | 20.9% | 80 | 22.9% | 40 | 11.5% | 3.66 | 1.50 |

| 11. I am engrossed in my work. | 28 | 8.0% | 73 | 20.9% | 76 | 21.8% | 79 | 22.6% | 62 | 17.8% | 31 | 8.9% | 3.48 | 1.43 |

| 12. I can work for extended amounts of time. | 37 | 10.6% | 70 | 20.1% | 68 | 19.5% | 66 | 18.9% | 83 | 23.8% | 25 | 7.2% | 3.47 | 1.48 |

| 13. My job is tough to me. | 39 | 11.2% | 71 | 20.3% | 64 | 18.3% | 83 | 23.8% | 53 | 15.2% | 39 | 11.2% | 3.45 | 1.52 |

| 14. I get carried away when working. | 40 | 11.5% | 88 | 25.2% | 58 | 16.6% | 76 | 21.8% | 61 | 17.5% | 26 | 7.4% | 3.31 | 1.49 |

| 15. I am very resilient mentally at work. | 30 | 8.6% | 65 | 18.6% | 72 | 20.6% | 89 | 25.5% | 60 | 17.2% | 33 | 9.5% | 3.52 | 1.43 |

| 16. It is difficult to remove myself from my job. | 38 | 10.9% | 67 | 19.2% | 73 | 20.9% | 72 | 20.6% | 74 | 21.2% | 25 | 7.2% | 3.44 | 1.46 |

| 17. At work, I always continue, even when things do not go well. | 22 | 6.3% | 70 | 20.1% | 76 | 21.8% | 87 | 24.9% | 63 | 18.1% | 31 | 8.9% | 3.55 | 1.39 |

| Total | 450 | 8% | 1358 | 23% | 1212 | 20% | 1277 | 22% | 1108 | 19% | 528 | 9% | 3.475 | 1.211 |

| Correlation | Mean of Total Work-Related Quality of Life (WRQoL) Scale | Mean of Total Work Engagement Scale | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean of total Work-Related Quality of Life (WRQoL) Scale | Pearson correlation | 1 | 0.804 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | ||

| N | 349 | 349 | |

| Mean of total Work Engagement Scale | Pearson correlation | 0.804 ** | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | ||

| n | 349 | 349 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alasiry, S.M.; Alfridi, F.N.; Bahri, H.A.; HamdanAlshehri, H. What Nurses’ Work–Life Balance in a Clinical Environment Would Be. Healthcare 2025, 13, 427. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13040427

Alasiry SM, Alfridi FN, Bahri HA, HamdanAlshehri H. What Nurses’ Work–Life Balance in a Clinical Environment Would Be. Healthcare. 2025; 13(4):427. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13040427

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlasiry, Sharifa M, Fauzia Naif Alfridi, Hibah Abdulrahim Bahri, and Hanan HamdanAlshehri. 2025. "What Nurses’ Work–Life Balance in a Clinical Environment Would Be" Healthcare 13, no. 4: 427. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13040427

APA StyleAlasiry, S. M., Alfridi, F. N., Bahri, H. A., & HamdanAlshehri, H. (2025). What Nurses’ Work–Life Balance in a Clinical Environment Would Be. Healthcare, 13(4), 427. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13040427