Training Nurses for Disasters: A Systematic Review on Self-Efficacy and Preparedness

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategies

2.3. Study Selection Process

2.4. Data Collection Process

2.5. Data Items

2.6. Studies’ Risk of Bias Assessment

2.7. Effect Measures

2.8. Synthesis Methods

2.9. Reporting Bias Assessment

3. Results

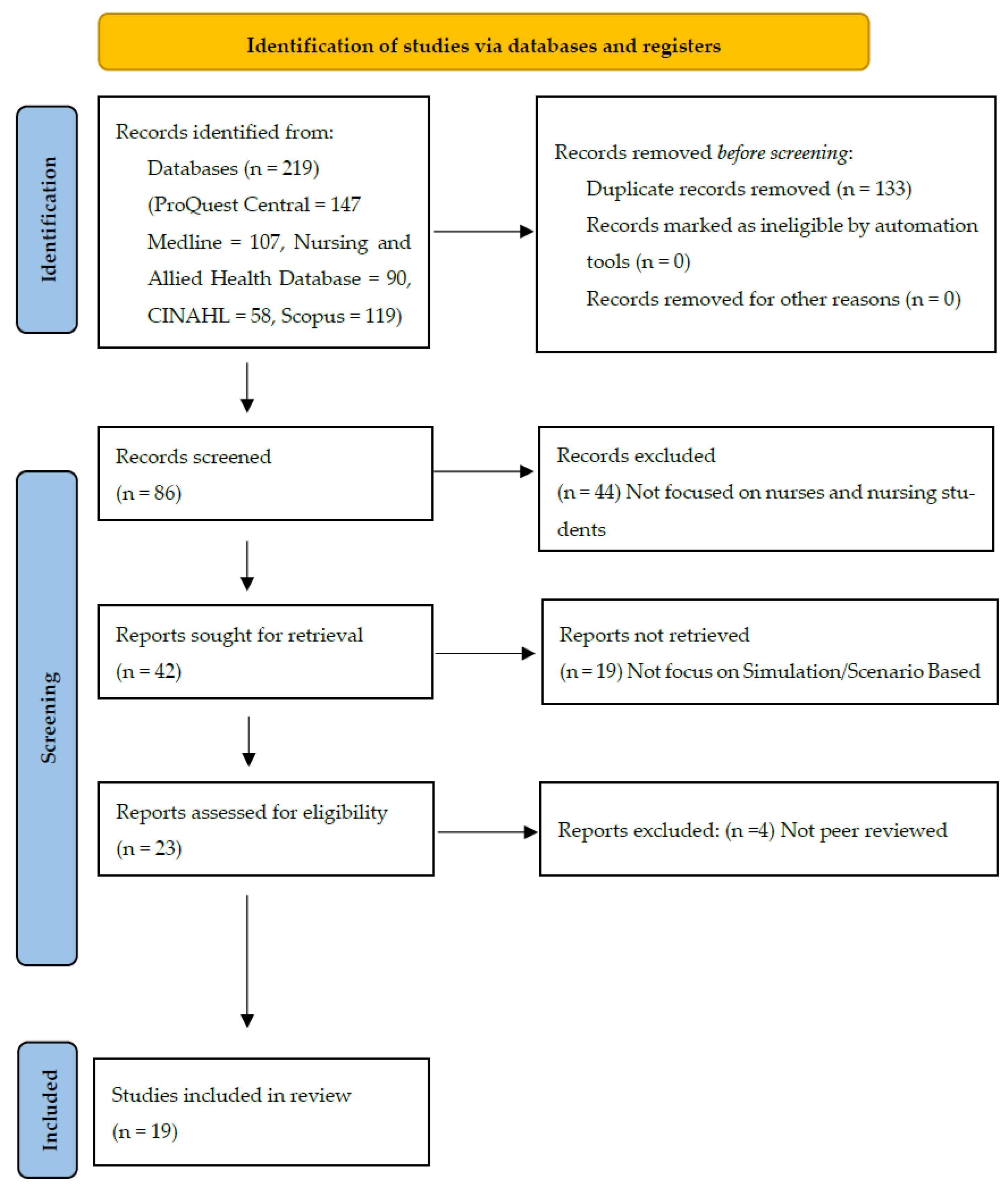

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Risk of Bias in Studies

4. Findings

4.1. Effectiveness of Structured Disaster Training Programs

4.2. Simulation- and Scenario-Based Approaches to Disaster Training

4.3. Competency-Based Disaster Nursing Education

4.4. Factors Influencing Disaster Preparedness and Response Willingness

4.5. Certainty of Evidence

5. Discussion

Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Authors/Date | Aim | Methodology | Sample | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emaliyawati, et al. (2025) [15] | To explore the effectiveness of the ISEL-DN model in enhancing knowledge, attitudes, satisfaction, and self-confidence among undergraduate nursing students. | A quasi-experimental study with a control group | 94 undergraduate nursing students (Intervention group: 47 and control group: 47) | The intervention group demonstrated significant improvements in knowledge, attitudes, satisfaction, and self-confidence from pretest to posttest (all p < 0.05), while the control group showed smaller gains, particularly limited in post-disaster knowledge and attitudes. |

| Phan, Q. T. et al. (2025) [21] | To implement and evaluate an innovative escape room and unfolding disaster preparedness simulation in a pre-licensure nursing program | Descriptive pilot evaluation design | 29 pre-licensure nursing students | The escape room and unfolding disaster simulation improved nursing students’ knowledge (100%), confidence (93–100%), and teamwork (96.6%), though fewer students reported clarity in their roles during the disaster scenario (45–55%). |

| Hsiao et al. (2024) [16] | To develop and evaluate the effectiveness of an immersive cinematic escape room (ICER) instructional approach in disaster preparedness and self-efficacy in nurses. | Quasi-experimental research design | 115 Nurses | The experimental group, lacking prior disaster preparedness education experiences, demonstrated a statistically significant improvement (p < 0.01) compared to the control group with more such experiences. At week four, both groups showed improvement in the self-efficacy scores, but the improvement did not achieve statistical significance (p > 0.05). |

| Hill, P. P. et al. (2025) [17] | To evaluate the effects of participating in a large-scale community disaster simulation on nursing students’ disaster preparedness and management competency, | Quasi experimental exploratory study, | senior nursing students (n = 44) | Students’ perceived competency dropped significantly after the simulation highlights educational gaps and the need for structured, ongoing disaster curricula. It shows how disaster simulations not only build technical skills but also reveal the emotional challenges of patient care in crises. |

| Hugh et al. (2019) [18] | To evaluate the impact of a disaster nursing educational program on disaster nursing competencies among Korean nursing students. | A quasi-experimental design was employed, with the experimental group receiving disaster nursing training on prevention, preparedness, response, and recovery stages, measuring knowledge, triage skills, and readiness. | −60 junior nursing students from two nursing colleges in Korea | Results showed significant improvements in the experimental group: knowledge (t = 14.37, p < 0.001), triage skills (t = 7.90, p = 0.002), and readiness (t = 10.82, p < 0.001). The program was effective in enhancing disaster nursing competency and is recommended for nursing education. |

| Lin, C. et al., (2024) [12] | To assess how well a structured DMTP (disaster management training program) affected nurses’ preparedness for disaster response. | The study divided into experimental and control groups evaluated disaster readiness across emergency response, clinical management, self-protection, and personal preparation at baseline and 12 weeks post-intervention. | 100 nurses in Taiwan | The study suggests structured DMTP with diverse teaching methods as an essential part of ongoing nursing education to enhance disaster preparedness across all four domains. |

| Hung et al. (2021) [3] | To evaluate the effectiveness of a disaster management training course in improving Hong Kong nursing students’ disaster knowledge, willingness, and perceived ability to respond to public health emergencies or disasters. | The study employed a mixed-method design, involving pre- and post-intervention comparisons and qualitative focus group interviews, to evaluate the effectiveness of a 45 h disaster management training course. | A total of 157 nursing students participated and completed the pre- and post-intervention questionnaires. | Concerns were divided into three categories: organizational support, personal risk perceptions, and catastrophe contextual variables. However, there were notable advancements in disaster knowledge and perceived capacity. |

| Koca, B. et al. (2020) [13] | To examine the impact of a six-module training program, utilizing the Jennings Disaster Nursing Management Model and a learning management system, on nursing students’ disaster preparedness perceptions. | A randomized controlled trial using a two-group comparison design, including an experimental group (EG) and a control group (CG). | Third-year nursing students from a city in western Turkey, with 127 in the experimental group and 108 in the control group. | The training program significantly improved disaster preparedness perceptions and response self-efficacy in the experimental group, while moderately affecting their knowledge and self-efficacy. |

| Jacobs-Wingo et al., (2016) [6] | To improve emergency preparedness among nurses for chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and explosive (CBRNE) events by addressing training and confidence gaps. | The CBRNE curriculum was developed through surveys, focus groups, and training sessions, identifying gaps in emergency preparedness among nursing staff in 20 NYC hospitals. | A study involving 7177 NYC nursing staff, 22 nurse educators, and 11 nurses conducted surveys, focus groups, and pilot training sessions. | The CBRNE curriculum, including six modules, just-in-time training, and an online refresher course, significantly enhanced nurses’ knowledge of CBRNE events, from 54% to 89% post-training. |

| Bilge Kalanlar (2018) [14] | To assessed the influence of disaster nursing education on undergraduate nursing students’ disaster preparedness and suggested enhancements in disaster preparedness education. | A quasi-experimental study compared knowledge and preparedness of final-year nursing students in a disaster nursing and management module with a control group, achieving a 90% success rate. | The study involved final-year undergraduate nursing students who chose the disaster nursing and management module as their treatment group. | The treatment group demonstrated a significant enhancement in disaster knowledge, preparedness, and management, indicating that the disaster nursing module effectively prepared students for disaster response and recovery. |

| Park and Kim (2017) [24] | To identify factors influencing the disaster nursing core competencies of emergency nurses. | A survey-based study was conducted using a questionnaire to collect data on disaster-related experience, attitude, knowledge, and disaster nursing core competencies. | The study included 231 emergency nurses working in 12 hospitals in South Korea. | Multiple regression analysis showed that disaster-related experience had the strongest influence on disaster nursing core competencies, followed by disaster-related knowledge. These factors explained 25.6% of the variance in disaster nursing core competencies, with statistical significance (F = 12.189, p < 0.001). The study highlighted the importance of education and training programs to improve nurses’ disaster preparedness. |

| Xia et al., (2020) [19] | To develop and evaluate a disaster nursing preparedness training program to improve nursing students’ knowledge, skills, and family preparedness in disaster situations. | An experimental pretest–posttest control group design was used. Participants were randomly assigned to either the experimental or control group. | 63 nursing students (31 in the experimental group, 32 in the control group). | Students in the training program showed greater improvements in knowledge and skills than those in the control group. These improvements remained one month after the intervention. However, there were no significant changes in attitude over time. |

| Ghahremani et al., (2022) [20] | To compare the effectiveness of simulation and workshop methods in improving nursing students’ knowledge and practice regarding bioterrorism. | An experimental study with pretest and posttest design. Data were collected using a demographic questionnaire, bioterrorism knowledge scale, and OSCE checklist. | 40 final-year nursing students, randomly assigned to two groups (20 in simulation, 20 in workshop). | Both groups showed significant improvements in knowledge and performance (p < 0.001). However, the simulation group outperformed the workshop group in knowledge and most performance domains. |

| Nilsson et al., (2016) [9] | To compare self-reported disaster nursing competence (DNC) between nursing students (NSs) and registered nurses (RNs) and explore associations between DNC and background factors. | A cross-sectional study using the 88-item Nurse Professional Competence Scale, including three DNC-related items. | 569 nursing students (NSs) and 227 registered nurses (RNs). | Registered nurses (RNs) had higher disaster nursing competence (DNC) than nursing students (NSs), especially in handling violence and applying disaster medicine. RNs in emergency care scored higher than those in other fields. Working night shifts and emergency care experience were linked to better DNC. Exposure to serious events improved nurses’ ability to manage disasters and follow safety rules. |

| Azizpour, Mehri and Soola, (2022) [23] | To assess disaster preparedness knowledge among hospital and pre-hospital emergency nurses and identify its predictors | A descriptive cross-sectional study conducted on 472 emergency nurses in Ardabil, Iran, using self-reported questionnaires (EPIQ and TDMI). Data were analyzed with SPSS. | 472 hospital and pre-hospital emergency nurses, selected through convenience sampling. | Emergency nurses had low disaster preparedness knowledge. Key predictors included triage decision-making, age, residence, prior training, disaster experience, and training organization (p < 0.05). Higher knowledge correlated with better triage skills. Improved training is recommended. |

| Al Thobaity, Williams and Plummer, (2016) [10] | To develop a valid and reliable scale to assess disaster nursing core competencies, roles, and barriers in Saudi Arabia. | A principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted using a self-report questionnaire with 93 items rated on a Likert scale. Data were collected from emergency nurses in two hospitals. | 132 emergency nurses (66% response rate) from two hospitals in Saudi Arabia. | PCA identified three key factors after removing 49 redundant items, leaving 44 items that explained 77.3% of the variance. The scale showed high reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.96 overall, and 0.98, 0.92, and 0.86 for the three factors. |

| Kang, Lee and Seo, (2022) [22] | To examine nursing students’ disaster awareness, preparedness, willingness to respond, and disaster nursing competency, and their relationships. | A descriptive study with 163 nursing students. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and Pearson’s correlation coefficients. | 163 nursing students. | Disaster awareness correlated positively with willingness to respond. Disaster preparedness and willingness to respond correlated positively with nursing competency. However, disaster awareness was not significantly linked to preparedness or competency, and preparedness did not correlate with willingness to respond. |

| Yeon Mi Park and Won Ju Hwang, (2024) [26] | This study aimed to develop and evaluate a simulation-based disaster nursing education program using standardized patients, based on the International Council of Nurses’ Framework of Disaster Nursing Competencies. | A quasi-experimental design with a pretest–posttest control group was used. The program included a 60 min lecture and two simulation scenarios. The effectiveness was measured through disaster nursing competencies, triage skills, preparedness, critical thinking, and confidence. | The study involved 140 senior nursing students from two universities | students in the simulation-based training group showed significant improvements in disaster nursing competencies, triage skills, preparedness, critical thinking, and confidence compared to the other groups (p < 0.001). This confirms the effectiveness of simulation-based training in disaster nursing education. |

| Tzeng et al., (2016) [25] | This study aimed to assess hospital nurses’ perceived readiness for disaster response and the factors influencing their willingness to work outside the hospital during disasters. | A cross-sectional research design was used. Data were collected through a 40-item self-administered questionnaire covering personal preparation, self-protection, emergency response, and clinical management. Statistical analysis included descriptive statistics, independent t-tests, and generalized linear models. | The study involved 311 registered nurses from a military hospital in Taiwan. | Most hospital nurses had poor readiness for disaster response. Their preparedness was strongly linked to disaster-related training, prior disaster response experience, and experience in emergency or intensive care settings. |

Appendix B. Search Strings for Databases

| CINAHL: (nursing students OR “student nurses” OR “undergraduate student nurses” OR nurse OR nurses OR nursing OR “nursing staff”) AND (“disaster preparedness” OR “disaster response” OR “disaster management” OR preparation OR preparedness OR readiness) AND (“simulation training” OR “simulation education” OR “simulation learning” OR “scenario based learning”) AND (self-efficacy OR “self efficacy” OR confidence OR “self esteem”) |

| ProQuest Central, Medline, Nursing and Allied Health Database (nursing students OR “student nurses” OR “undergraduate student nurses” OR nurse OR nurses OR nursing OR “nurs-ing staff”) AND (“disaster preparedness” OR “disaster response” OR “disaster management” OR preparation OR preparedness OR read-iness) AND (“simulation training” OR “simulation education” OR “simulation learning” OR “scenario based learning”) AND (self-efficacy OR “self efficacy” OR confidence OR “self esteem”) |

| Scopus: ((nursing students OR “student nurses” OR “undergraduate student nurses” OR nurse OR nurses OR nursing OR “nursing staff”) AND (“disaster preparedness” OR “disaster response” OR “disaster management” OR preparation OR preparedness OR readiness) AND (“simulation training” OR “simulation education” OR “simulation learning” OR “scenario based learning”) AND (self-efficacy OR “self efficacy” OR confidence OR “self esteem”)) |

References

- Lim, J.; Skidmore, M. Natural Disasters: Impacts and Recovery. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Economics and Finance; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2025; Available online: https://oxfordre.com/economics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190625979.001.0001/acrefore-9780190625979-e-973 (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Topluoglu, S.; Taylan-Ozkan, A.; Alp, E. Impact of wars and natural disasters on emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1215929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hung, M.S.Y.; Lam, S.K.K.; Chow, M.C.M.; Ng, W.W.M.; Pau, O.K. The Effectiveness of Disaster Education for Undergraduate Nursing Students’ Knowledge, Willingness, and Perceived Ability: An Evaluation Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Health Emergency and Disaster Risk Management Framework; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241516181 (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC). Types of Disasters: Definition of Hazard. 2020. Available online: https://alnap.org/help-library/resources/ifrc-types-of-disasters/ (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Jacobs-Wingo, J.L.; Schlegelmilch, J.; Berliner, M.; Airall-Simon, G.; Lang, W. Emergency Preparedness Training for Hospital Nursing Staff, New York City, 2012–2016. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2018, 51, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ličen, S.; Prosen, M. Disaster Nursing Competencies in a Time of Global Conflicts and Climate Crises: A Cross-Sectional Survey Study. Int Nurs Rev. 2025, 72, e70052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Achora, S.; Kamanyire, J.K. Disaster preparedness: Need for inclusion in undergraduate nursing education. Nurse Educ. Today 2017, 48, 74–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, J.; Johansson, E.; Carlsson, M.; Florin, J.; Leksell, J.; Lepp, M.; Lindholm, C.; Nordström, G.; Theander, K.; Wilde-Larsson, B.; et al. Disaster nursing: Self-reported competence of nursing students and registered nurses, with focus on their readiness to manage violence, serious events and disasters. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2016, 17, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Thobaity, A.; Williams, B.; Plummer, V. A new scale for disaster nursing core competencies: Development and psychometric testing. Australas. Emerg. Nurs. J. 2016, 19, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lin, C.-H.; Tzeng, W.-C.; Chiang, L.-C.; Lu, M.-C.; Lee, M.-S.; Chiang, S.-L. Effectiveness of a Structured Disaster Management Training Program on Nurses’ Disaster Readiness for Response to Emergencies and Disasters: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Nurs. Manag. 2024, 2024, 5551894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koca, B.; Arkan, G. The effect of the disaster management training program among nursing students. Public Health Nurs. 2020, 37, 769–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalanlar, B. Effects of disaster nursing education on nursing students’ knowledge and preparedness for disasters. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 28, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emaliyawati, E.; Ibrahim, K.; Trisyani, Y.; Songwathana, P. The Effect of Integrated Simulation Experiential Learning Disaster Nursing for Enhancing Learning Outcomes Among Undergraduate Nursing Students: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 2025, 16, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiao, C.-C.; Huang, C.-Y.; Lai, F.-C.; Chen, T.-L.; Cheng, S.-F. Development and Evaluation of an Immersive Cinematic Escape Room for Disaster Preparedness and Self-Efficacy Among Nurses. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2024, 91, 101541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, P.P.; Díaz, D.A.; D’Amato-Kubiet, L.A. Disaster! The Effects of a Large-Scale Simulation on Nursing Students’ Disaster Competence. J. Nurs. Educ. 2025, 64, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, S.-S.; Kang, H.-Y. Effects of an educational program on disaster nursing competency. Public Health Nurs. 2019, 36, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, R.; Li, S.; Chen, B.; Jin, Q.; Zhang, Z. Evaluating the effectiveness of a disaster preparedness nursing education program in Chengdu, China. Public Health Nurs. 2020, 37, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahremani, M.; Rooddehghan, Z.; Varaei, S.; Haghani, S. Knowledge and practice of nursing students regarding bioterrorism and emergency preparedness: Comparison of the effects of simulations and workshop. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, Q.T.; Chance-Revels, R.; Clark-Youngblood, M.; Baker, H.; Kimble, L.P. Integrating Disease Investigation Escape Room and Preparedness Simulation into Nursing Education. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2025, 19, e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.-S.; Lee, H.; Seo, J.M. Relationship Between Nursing Students’ Awareness of Disaster, Preparedness for Disaster, Willingness to Participate in Disaster Response, and Disaster Nursing Competency. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2022, 17, e220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizpour, I.; Mehri, S.; Soola, A.H. Disaster preparedness knowledge and its relationship with triage decision-making among hospital and pre-hospital emergency nurses—Ardabil, Iran. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.-Y.; Kim, J.-S. Factors influencing disaster nursing core competencies of emergency nurses. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2017, 37, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzeng, W.-C.; Feng, H.-P.; Cheng, W.-T.; Lin, C.-H.; Chiang, L.-C.; Pai, L.; Lee, C.-L. Readiness of hospital nurses for disaster responses in Taiwan: A cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ. Today 2016, 47, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.M.; Hwang, W.J. Development and Effect of a Simulation-Based Disaster Nursing Education Program for Nursing Students Using Standardized Patients. J. Nurs. Res. 2024, 32, e314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Integrating Emergency Preparedness and Response into Undergraduate Nursing Curricula: Report on a WHO Meeting; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008; Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/70069/WHO_HAC_BRO_08.7_eng.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- International Council of Nurses (ICN). ICN Framework of Disaster Nursing Competencies; ICN: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009; Available online: https://www.icn.ch/sites/default/files/inline-files/ICN_Disaster-Comp-Report_WEB.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Jose, M.M.; Dufrene, C. Educational competencies and technologies for disaster preparedness in undergraduate nursing education: An integrative review. Nurse Educ. Today 2014, 34, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genç, F.Z.; Yiğitbaş, Ç.; Uzun, Ö. Effect of structured digital-based education on disaster literacy and preparedness beliefs among nursing students: A randomized controlled study. Nurse Educ. Today 2025, 147, 106581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılınç, G.; Yıldız, E.; Harmanci, P. Bandura’s Social Learning and Role Model Theory in Nursing Education. 2018. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329814373_Bandura (accessed on 20 May 2025).

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Publication Years | Published between 2014–2025 | Published before 1 January 2014 and after 30 July 2025 |

| Language | Articles published in English | Non-English language articles without translation |

| Type | Peer-reviewed Research Articles | Not peer-reviewed |

| Topic Focus | Articles focused on nursing disaster preparedness, education | Studies unrelated to nursing or disaster preparedness (e.g., friendship, military, non-healthcare contexts) |

| Population (P) | Intervention (I) | Comparison (C) | Outcomes (O) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (nursing students OR “student nurses” OR “undergraduate student nurses” OR nurse OR nurses OR nursing OR “nursing staff”) | AND | (“disaster preparedness” OR “disaster response” OR “disaster management” OR preparation OR preparedness OR readiness) | AND | (“simulation training” OR “simulation education” OR “simulation learning” OR “scenario based learning”) | AND | (self-efficacy OR “self efficacy” OR confidence OR “self esteem”) |

| Author (Year) | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Q12 | Q13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lin et al. (2024) [12] | √ | √ | √ | √ | No | X | No | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Koca et al. (2020) [13] | √ | √ | √ | √ | No | √ | No | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Author (Year) | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kalanlar (2018) [14] | √ | √ | √ | No | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Hung et al. (2021) [3] | √ | √ | √ | No | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Emaliyawati et al. (2025) [15] | √ | √ | √ | No | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Hsiao et al. (2024) [16] | √ | √ | √ | No | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Hill et al. (2025) [17] | √ | √ | √ | No | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Huh S-S, Kang H-Yet al. (2019) [18] | √ | √ | √ | No | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Xia et al. (2020) [19] | √ | √ | √ | No | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Ghahremani et al. (2022) [20] | √ | √ | √ | No | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Phan et al. (2025) [21] | √ | √ | √ | No | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Ja-cobs-Wingo et al. (2016) [6] | √ | √ | √ | No | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Al Thobaity et al. (2016) [10] | √ | √ | √ | No | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nikitara, M.; Kalu, A.; Latzourakis, E.; Constantinou, C.S.; Velonaki, V.S. Training Nurses for Disasters: A Systematic Review on Self-Efficacy and Preparedness. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3323. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243323

Nikitara M, Kalu A, Latzourakis E, Constantinou CS, Velonaki VS. Training Nurses for Disasters: A Systematic Review on Self-Efficacy and Preparedness. Healthcare. 2025; 13(24):3323. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243323

Chicago/Turabian StyleNikitara, Monica, Amarachi Kalu, Evangelos Latzourakis, Costas S. Constantinou, and Venetia Sofia Velonaki. 2025. "Training Nurses for Disasters: A Systematic Review on Self-Efficacy and Preparedness" Healthcare 13, no. 24: 3323. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243323

APA StyleNikitara, M., Kalu, A., Latzourakis, E., Constantinou, C. S., & Velonaki, V. S. (2025). Training Nurses for Disasters: A Systematic Review on Self-Efficacy and Preparedness. Healthcare, 13(24), 3323. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243323