Bridging the Knowledge Gap: A National Survey on MASLD Awareness and Management Barriers in the Saudi Population

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Setting

2.2. Study Tool

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

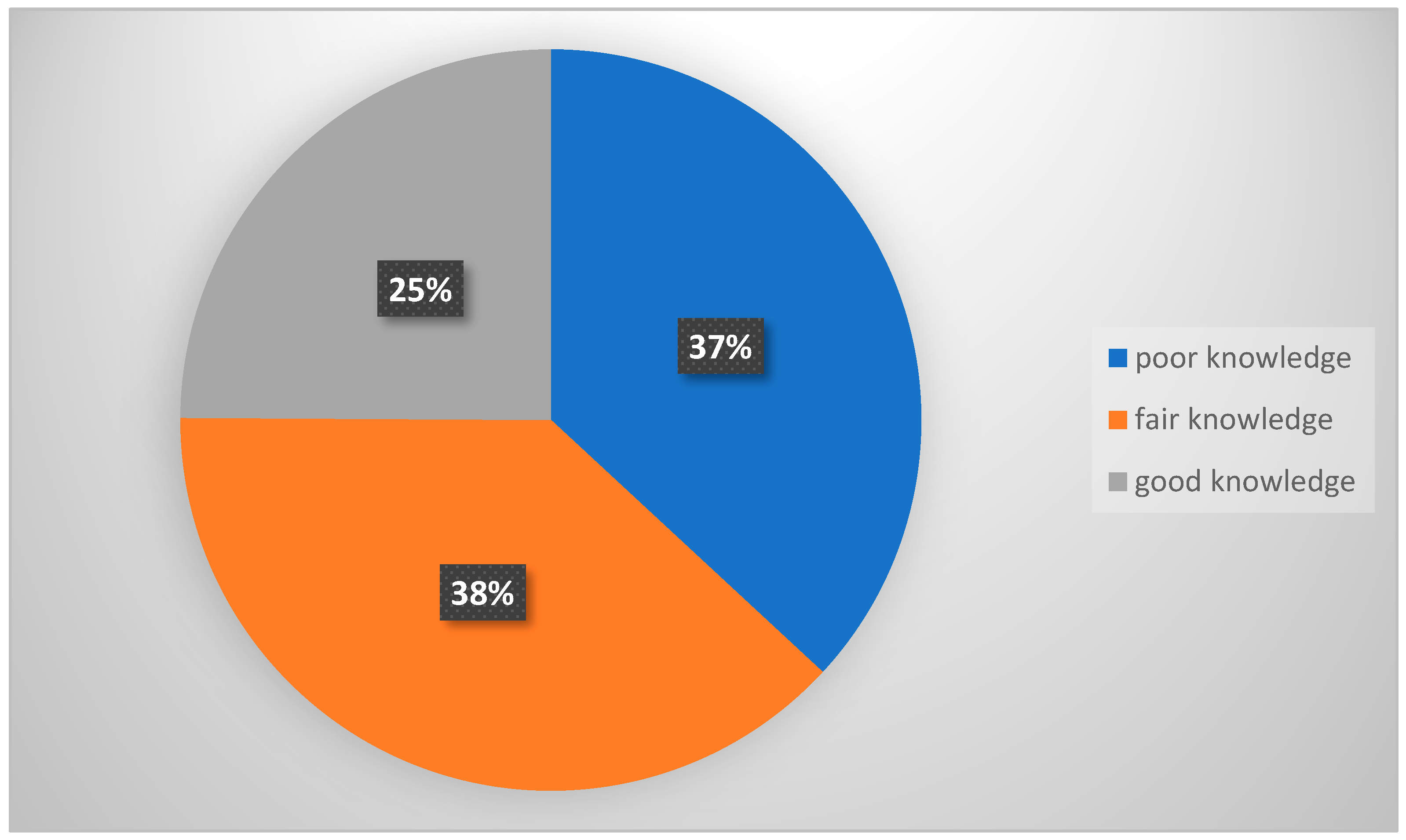

3.1. Knowledge of Participants About NAFLD

3.2. Attitude of Participants About NAFLD

3.3. Current NAFLD Management Status and Barriers

3.4. Perceptions on Long-Term Management and Program Participation

4. Discussion

5. Recommendations

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, J.-H.; Jung, J.H.; Park, H.; Oh, J.H.; Ahn, S.B.; Yoon, E.L.; Jun, D.W. A survey on the awareness, current management, and barriers for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease among the general Korean population. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinella, M.E.; Sookoian, S. From NAFLD to MASLD: Updated naming and diagnosis criteria for fatty liver disease. J. Lipid Res. 2023, 65, 100485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Priyadarshi, R.N.; Anand, U. Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Growing Burden, Adverse Outcomes and Associations. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2020, 8, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenezi, Y.M.; Harris, R.; Morling, J.; Card, T. Prevalence of Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) in Saudi Arabia: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Cureus 2023, 15, e40308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhong, G.-C.; Tan, H.-Y.; Hao, F.-B.; Hu, J.-J. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: A meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanwal, F.; Kramer, J.R.; Mapakshi, S.; Natarajan, Y.; Chayanupatkul, M.; Richardson, P.A.; Li, L.; Desiderio, R.; Thrift, A.P.; Asch, S.M.; et al. Risk of Hepatocellular Cancer in Patients with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 1828–1837.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wójcik-Cichy, K.; Koślińska-Berkan, E.; Piekarska, A. The influence of NAFLD on the risk of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular diseases. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 2018, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alon, L.; Corica, B.; Raparelli, V.; Cangemi, R.; Basili, S.; Proietti, M.; Romiti, G.F. Risk of cardiovascular events in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2021, 29, 938–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantovani, A.; Byrne, C.D.; Bonora, E.; Targher, G. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Risk of Incident Type 2 Diabetes: A Meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musso, G.; Gambino, R.; Tabibian, J.H.; Ekstedt, M.; Kechagias, S.; Hamaguchi, M.; Hultcrantz, R.; Hagström, H.; Yoon, S.K.; Charatcharoenwitthaya, P.; et al. Association of Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease with Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2014, 11, e1001680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, S.H.; Walker, J.J.; Morling, J.R.; McAllister, D.A.; Colhoun, H.M.; Farran, B.; McGurnaghan, S.; McCrimmon, R.; Read, S.H.; Sattar, N.; et al. Cardiovascular Disease, Cancer, and Mortality Among People with Type 2 Diabetes and Alcoholic or Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Hospital Admission. Diabetes Care 2017, 41, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, A.M.; Therneau, T.M.; Larson, J.J.; Coward, A.; Somers, V.K.; Kamath, P.S. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease incidence and impact on metabolic burden and death: A 20 year-community study. Hepatology 2017, 67, 1726–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Dhaliwal, A.S.; Singh, S.; Kumar, A.; Lopez, R.; Gupta, M.; Noureddin, M.; Carey, W.; McCullough, A.; Alkhouri, N. Awareness of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Is Increasing but Remains Very Low in a Representative US Cohort. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2019, 65, 978–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieland, A.C.; Mettler, P.B.; McDermott, M.T.; Crane, L.A.; Cicutto, L.C.P.; Bambha, K.M.M. Low Awareness of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Among Patients at High Metabolic Risk. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2015, 49, e6–e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Someili, A.M.; Mohrag, M.; Rajab, B.S.; A Daghreeri, A.; Hakami, F.M.; A Jahlan, R.; A Otaif, A.; A Otaif, A.; Hakami, H.T.; Daghriri, B.F.; et al. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Determinants of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Among Adults in Jazan Province: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus 2024, 16, e66837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.J.; Banh, X.; Horsfall, L.U.; Hayward, K.L.; Hossain, F.; Johnson, T.; Stuart, K.A.; Brown, N.N.; Saad, N.; Clouston, A.; et al. Underappreciation of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by primary care clinicians: Limited awareness of surrogate markers of fibrosis. Intern. Med. J. 2017, 48, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blais, P.; Husain, N.; Kramer, J.R.; Kowalkowski, M.; El-Serag, H.; Kanwal, F. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease is Underrecognized in the Primary Care Setting. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 110, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Tincopa, M.; Wong, J.; Fetters, M.; Lok, A.S. Patient disease knowledge, attitudes and behaviours related to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A qualitative study. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2021, 8, e000634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. Approves First Treatment for Patients with Liver Scarring Due to Fatty Liver Disease. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-treatment-patients-liver-scarring-due-fatty-liver-disease#:~:text=In%20this%20section-,Press%20Announcements,pressure%20and%20type%202%20diabetes (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Shen, K.; Singh, A.D.; Esfeh, J.M.; Wakim-Fleming, J. Therapies for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A 2022 update. World J. Hepatol. 2022, 14, 1718–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadden, T.A.; Tronieri, J.S.; Butryn, M.L. Lifestyle modification approaches for the treatment of obesity in adults. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayedi, A.; Soltani, S.; Emadi, A.; Zargar, M.-S.; Najafi, A. Aerobic Exercise and Weight Loss in Adults. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2452185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sample Size Calculator. Available online: http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html (accessed on 27 February 2024).

- Faiyaz, S.S.M.; Zafar, M.; Jameel, S.A.M.; Alharbi, F.M.G.; Alameen, A.A.S.; Alam Shahid, S.M. Assessing Knowledge, Attitudes, and Factors Influencing Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease among Adults in Saudi Arabia. Asian J. Pharm. Res. Health Care 2025, 17, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulfattah, A.A.; Elmakki, E.E.; Maashi, B.I.; Alfaifi, B.A.; Almalki, A.S.; Alhadi, N.A.; Majrabi, H.; Kulaybi, A.; Salami, A.; Hakami, F.I. Awareness of Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Its Determinants in Jazan, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus 2024, 16, e53111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamri, A.S.; Alhomrani, M.; Alsanie, W.F.; O AlMerdas, M.; A AlGhamdi, W.; AlTwairqi, W.F.; Alotaibi, N.M.; AlOsaimi, S.S.; Asdaq, S.M.B.; Sreeharsha, N.; et al. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Taif Populations’ Perspective Based on Knowledge and Attitude Determinants. Indian J. Pharm. Educ. Res. 2021, 55, 924–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, M.L.; Ng, C.H.; Huang, D.Q.; Chan, K.E.; Tan, D.J.; Lim, W.H.; Yang, J.D.; Tan, E.; Muthiah, M.D. Global incidence and prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2023, 29, S32–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.M.; Lai, L.S.W.; Wong, W.H.; Chan, K.H.; Luk, Y.W.; Lai, J.Y.; Yeung, Y.W.; Hui, W.M. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: An expanding problem with low levels of awareness in Hong Kong. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2009, 24, 1786–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghevariya, V.; Sandar, N.; Patel, K.; Ghevariya, N.; Shah, R.; Aron, J.; Anand, S. Knowing What’s Out There: Awareness of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Front. Med. 2014, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.; Tacke, F.; Arrese, M.; Sharma, B.C.; Mostafa, I.; Bugianesi, E.; Wong, V.W.-S.; Yilmaz, Y.; George, J.; Fan, J.; et al. Global Perspectives on Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Hepatology 2019, 69, 2672–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.J.; Kim, B.-H.; Seo, H.S.; Lee, Y.J.; Kim, H.H.; Son, H.-H.; Choi, M.H. Cholesterol-Induced Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Atherosclerosis Aggravated by Systemic Inflammation. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsulami, S.; Baig, M.; Ahmad, T.; Althagafi, N.; Hazzazi, E.; Alsayed, R.; Alghamdi, M.; Almohammadi, T. Obesity prevalence, physical activity, and dietary practices among adults in Saudi Arabia. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1124051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radu, F.; Potcovaru, C.-G.; Salmen, T.; Filip, P.V.; Pop, C.; Fierbințeanu-Braticievici, C. The Link between NAFLD and Metabolic Syndrome. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmanizadeh, F.; Sabzevari, S.; Shafieipour, S.; Zahedi, M.J.; Sarafinejad, A. Challenges and needs in the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease from the perspective of gastroenterology and hepatology specialists: A qualitative study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2025, 25, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.; Ko, K.S.; Rhee, B.D. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) Management in the Community. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, Y.; Kim, B.H.; Park, J.-W. Preventive strategy for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2023, 29, S220–S227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, J.P.; Henry, Z.H.; Argo, C.K.; Northup, P.G. Relationship of Physician Counseling to Weight Loss Among Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: An Observational Cohort Study Using National Health and Education Survey Data. Clin. Liver Dis. 2019, 14, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, V.W.; Zelber-Sagi, S.; Cusi, K.; Carrieri, P.; Wright, E.; Crespo, J.; Lazarus, J.V. Management of NAFLD in primary care settings. Liver Int. 2022, 42, 2377–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, K.T.; Henneberg, C.J.; Wilechansky, R.M.; Long, M.T. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Obesity Treatment. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2019, 8, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, L.; Exley, C.; McPherson, S.; Trenell, M.I.; Anstee, Q.M.; Hallsworth, K. Lifestyle Behavior Change in Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Qualitative Study of Clinical Practice. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 15, 1968–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moolla, A.; Motohashi, K.; Marjot, T.; Shard, A.; Ainsworth, M.; Gray, A.; Holman, R.; Pavlides, M.; Ryan, J.D.; Tomlinson, J.W.; et al. A multidisciplinary approach to the management of NAFLD is associated with improvement in markers of liver and cardio-metabolic health. Front. Gastroenterol. 2019, 10, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 231 (46) |

| Female | 271 (54) |

| Age | |

| 18–24 | 257 (51.2) |

| 25–33 | 53 (10.6) |

| 34–51 | 122 (24.3) |

| 52–64 | 57 (11.4) |

| >65 | 9 (1.8) |

| Job | |

| Employer | 172 (34.3) |

| Unemployed | 45 (9.0) |

| Students | 240 (47.8) |

| Retired | 45 (9.0) |

| Education level | |

| High school | 88 (17.5) |

| University | 384 (76.3) |

| Postgraduate | 30 (6.0) |

| body index | |

| below normal | 36 (7.2) |

| Normal | 230 (45.8) |

| Overweight | 148 (29.5) |

| Obesity | 34 (6.8) |

| I don’t know | 54 (10.8) |

| Variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Do you think you can get fatty liver without drinking alcohol? | |

| Yes | 226 (45) |

| No | 69 (13.7) |

| I don’t know | 207 (41.2) |

| Have you ever heard of the term “non-alcoholic fatty liver disease” or “fatty liver” | |

| Yes | 237 (47.2) |

| No | 265 (52.8) |

| Do you think non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is a disease that requires hospital treatment? | |

| Agree | 300 (59.8) |

| Disagree | 27 (5.4) |

| I don’t know | 175 (34.9) |

| NAFLD is life-threatening | |

| Yes | 255 (50.8) |

| No | 34 (6.8) |

| I don’t know | 212 (42.2) |

| Methods for diagnosis | |

| Body mass index | 40 (8) |

| Ultra sound | 40 (8) |

| Blood test | 49 (9.8) |

| All the above | 236 (47.6) |

| I don’t know | 133 (26.5) |

| Variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Change the diet (reduce sugars, processed foods, and saturated fats) | 333 (66.3) |

| Physical activity | 326 (64.9) |

| Controlling blood sugar levels for patients with diabetes, using medications if necessary | 171 (34.3) |

| Vitamins | 155 (30.9) |

| Lowering cholesterol and triglyceride levels through diet and medication if necessary | 275 (54.8) |

| Eat a balanced diet rich in vegetables, fruits, and healthy proteins, with an emphasis on fiber and whole grains. | 305 (60.8) |

| Variables | Knowledge Levels | 95% Confidence Interval (CI) | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good n (%) | Fair n (%) | Poor n (%) | Total | |||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 61 (26.4) | 91 (39.4) | 79 (34.2) | 231 | 0.2 to 0.4 | 0.514 |

| Female | 64 (23.6) | 101 (37.3) | 106 (39.1) | 271 | 0.18 to 0.4 | |

| Age | ||||||

| 18–24 | 42 (16.3) | 108 (42.0) | 107 (41.6) | 257 | 0.1 to 0.5 | 0.002 * |

| 25–33 | 17 (29.8) | 20 (35.1) | 20 (35.1) | 57 | 0.2 to 0.5 | |

| 34–51 | 43 (35.2) | 38 (31.1) | 41 (33.6) | 122 | 0.2 to 0.4 | |

| 52–64 | 21 (36.8) | 21 (36.8) | 15 (26.3) | 57 | 0.1 to 0.6 | |

| 65 and above | 2 (22.2) | 5 (55.6) | 2 (22.2) | 9 | 0.03 to 1.3 | |

| Job | ||||||

| Employer | 58 (33.7) | 55 (32.0) | 59 (34.3) | 172 | 0.24 to 0.44 | 0.001 * |

| Unemployed | 14 (31.1) | 18 (40.0) | 13 (28.9) | 45 | 0.15 to 0.63 | |

| Students | 38 (15.8) | 99 (41.3) | 103 (42.9) | 240 | 0.11 to 0.52 | |

| Retired | 15 (33.3) | 20 (44.4) | 10 (22.2) | 45 | 0.11 to 0.69 | |

| Education level | ||||||

| High school | 23 (26.1) | 37 (42.0) | 29 (31.8) | 88 | 0.16 to 0.58 | 0.008 * |

| University | 87 (22.7) | 145 (37.8) | 152 (39.6) | 384 | 0.18 to 0.46 | |

| Postgraduate | 15 (50.0) | 10 (33.3) | 5 (16.7) | 30 | 0.05 to 0.82 | |

| Body mass index | ||||||

| Below normal | 5 (13.9) | 15 (41.7) | 16 (44.4) | 36 | 0.05 to 0.72 | 0.230 |

| Normal | 52 (22.6) | 88 (38.3) | 90 (39.1) | 230 | 0.16 to 0.48 | |

| Overweight | 45 (30.4) | 56 (37.8) | 47 (31.8) | 148 | 0.22 to 0.49 | |

| Obesity | 13 (38.2) | 11 (32.4) | 10 (29.4) | 34 | 0.14 to 0.58 | |

| I don’t know | 10 (18.5) | 22 (40.7) | 22 (40.7) | 54 | 0.09 to 0.62 | |

| Variables | Yes n (%) | No n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Do you believe that obesity causes NAFLD | 243 (48.4) | 259 (51.6) |

| Do you believe that NAFLD is caused by diabetes? | 146 (29.1) | 356 (70.9) |

| Do you believe that hypertension affects NAFLD? | 120 (23.9) | 382 (76.1) |

| Do you believe that liver cancer can be caused by NAFLD? | 215 (42.8) | 287 (57.2) |

| Do you believe that high blood cholesterol cause NAFLD? | 260 (51.8) | 242 (48.2) |

| Do you think that NAFLD can cause cardiovascular diseases | 149 (29.7) | 353 (70.3) |

| Variables | Knowledge Levels | 95% Confidence Interval (CI) | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good n (%) | Fair n (%) | Poor n (%) | Total | |||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 64 (27.7) | 83 (35.9) | 84 (36.4) | 231 | 0.23 to 0.45 | 0.520 |

| Female | 68 (25.1) | 91 (33.6) | 112 (41.3) | 271 | 0.19 to 0.49 | |

| Age | ||||||

| 18–24 | 72 (28.0) | 82 (31.9) | 103 (40.1) | 257 | 0.22 to 0.49 | 0.614 |

| 25–33 | 12 (21.1) | 23 (40.4) | 22 (38.6) | 57 | 0.11 to 0.61 | |

| 34–51 | 26 (21.3) | 47 (38.5) | 49 (40.2) | 122 | 0.14 to 0.51 | |

| 52–64 | 19 (33.3) | 18 (31.6) | 20 (35.1) | 57 | 0.18 to 0.54 | |

| 65 and above | 3 (33.3) | 4 (44.4) | 2 (22.2) | 9 | 0.07 to 1.1 | |

| Job | ||||||

| Employer | 43 (25.0) | 62 (36.0) | 67 (39.0) | 172 | 0.18 to 0.49 | 0.725 |

| Unemployed | 9 (20.0) | 17 (37.8) | 19 (42.2) | 45 | 0.09 to 0.66 | |

| Students | 70 (29.2) | 76 (31.7) | 94 (39.2) | 240 | 0.23 to 0.47 | |

| Retired | 10 (22.2) | 19 (42.2) | 16 (35.6) | 45 | 0.11 to 0.58 | |

| Education level | ||||||

| High school | 26 (29.5) | 33 (37.5) | 29 (33.0) | 88 | 0.19 to 52 | 0.261 |

| University | 94 (24.5) | 132 (34.4) | 158 (41.1) | 384 | 0.19 to 0.48 | |

| Postgraduate | 12 (40.0) | 9 (30.0) | 9 (30.0) | 30 | 0.13 to 0.69 | |

| Body mass index | ||||||

| Under normal | 8 (22.2) | 8 (22.2) | 20 (55.6) | 36 | 0.01 to 0.85 | 0.084 |

| Normal | 62 (27.0) | 73 (31.7) | 95 (41.3) | 230 | 0.21 to 0.51 | |

| Overweight | 43 (29.1) | 57 (38.5) | 48 (32.4) | 148 | 0.21 to 0.49 | |

| Obesity | 11 (32.4) | 14 (41.2) | 9 (26.5) | 34 | 0.12 to 0.69 | |

| I don’t know | 8 (14.8) | 22 (40.7) | 24 (44.4) | 54 | 0.06 to 0.66 | |

| Variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Diagnosis with NAFLD | |

| Yes | 39 (7.8) |

| No | 453 (92.2) |

| During your hospital visit, have you been recommended to change your lifestyle? | |

| Yes | 29 (74.4) |

| No | 10 (25.6) |

| Did you visit the hospital for more tests and management of NAFLD? | |

| Yes (go to the prevention/management question) | 24 (61.5) |

| No (go to the reason question) | 15 (38.5) |

| Your reason for not following-up with another hospital visit? (Multiple answers allowed) (n = 15) | |

| Not considered fatty liver a serious disease. | 5 (33.3) |

| I believed that by changing my lifestyle on my own, I could control the illness (weight management, exercise management, etc.). | 7 (46.7) |

| Lack of time to visit the hospital. | 2 (13.3) |

| The cost of medical care. | 4 (26.7) |

| My doctor has never advised me that I require illness management. | 5 (46.7) |

| Prevention/management of NAFLD (Multiple answers allowed) (n = 24) | |

| I am not managing my NAFLD in any specific way. | 8 (33.3) |

| Supplements for hyperlipidemia and the liver are available at pharmacies or online. | 5 (20.8) |

| Hospital-prescribed drugs for hyperlipidemia and liver. | 6 (25) |

| Reduction in calorie intake. | 5 (20.8) |

| Increase in the amount of exercise. | 7 (29.2) |

| Weight loss. | 10 (41.7) |

| Variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| What do you think is the most important aspect of managing long-term non-alcoholic fatty liver disease? (Multiple answers) | |

| Make time for lifestyle changes | 320 (63.7) |

| Health with treatment costs | 221 (44) |

| Providing nutritional advice and periodic management by a nutritionist | 286 (57) |

| Providing advice on how to exercise and periodic management by a sports specialist | 232 (46.2) |

| Instructions on proper diet and exercise provided by a physician | 283 (56.4) |

| If there is a mobile app for the prevention or management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, would you be willing to participate? | |

| Strongly agree | 172 (34.3) |

| Agree | 47 (9.4) |

| Neutral | 122 (24.3) |

| Disagree | 61 (12.2) |

| Strongly disagree | 100 (19.9) |

| If there is a program to visit public health centers to prevent or manage non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, would you be willing to participate? | |

| Willing to actively participate | 172 (34.3) |

| Willing to participate | 47 (9.4) |

| Neutral | 122 (24.3) |

| Little interest in participating | 61 (12.2) |

| No interest in participating | 100 (19.9) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alwhaibi, A.; Mansy, W.; Syed, W.; Babelghaith, S.D.; N-Alarifi, M. Bridging the Knowledge Gap: A National Survey on MASLD Awareness and Management Barriers in the Saudi Population. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3322. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243322

Alwhaibi A, Mansy W, Syed W, Babelghaith SD, N-Alarifi M. Bridging the Knowledge Gap: A National Survey on MASLD Awareness and Management Barriers in the Saudi Population. Healthcare. 2025; 13(24):3322. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243322

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlwhaibi, Abdulrahman, Wael Mansy, Wajid Syed, Salmeen D. Babelghaith, and Mohamed N-Alarifi. 2025. "Bridging the Knowledge Gap: A National Survey on MASLD Awareness and Management Barriers in the Saudi Population" Healthcare 13, no. 24: 3322. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243322

APA StyleAlwhaibi, A., Mansy, W., Syed, W., Babelghaith, S. D., & N-Alarifi, M. (2025). Bridging the Knowledge Gap: A National Survey on MASLD Awareness and Management Barriers in the Saudi Population. Healthcare, 13(24), 3322. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243322