Feasibility and Preliminary Response of a Novel Training Program on Mobility Parameters in Adolescents with Movement Disorders

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

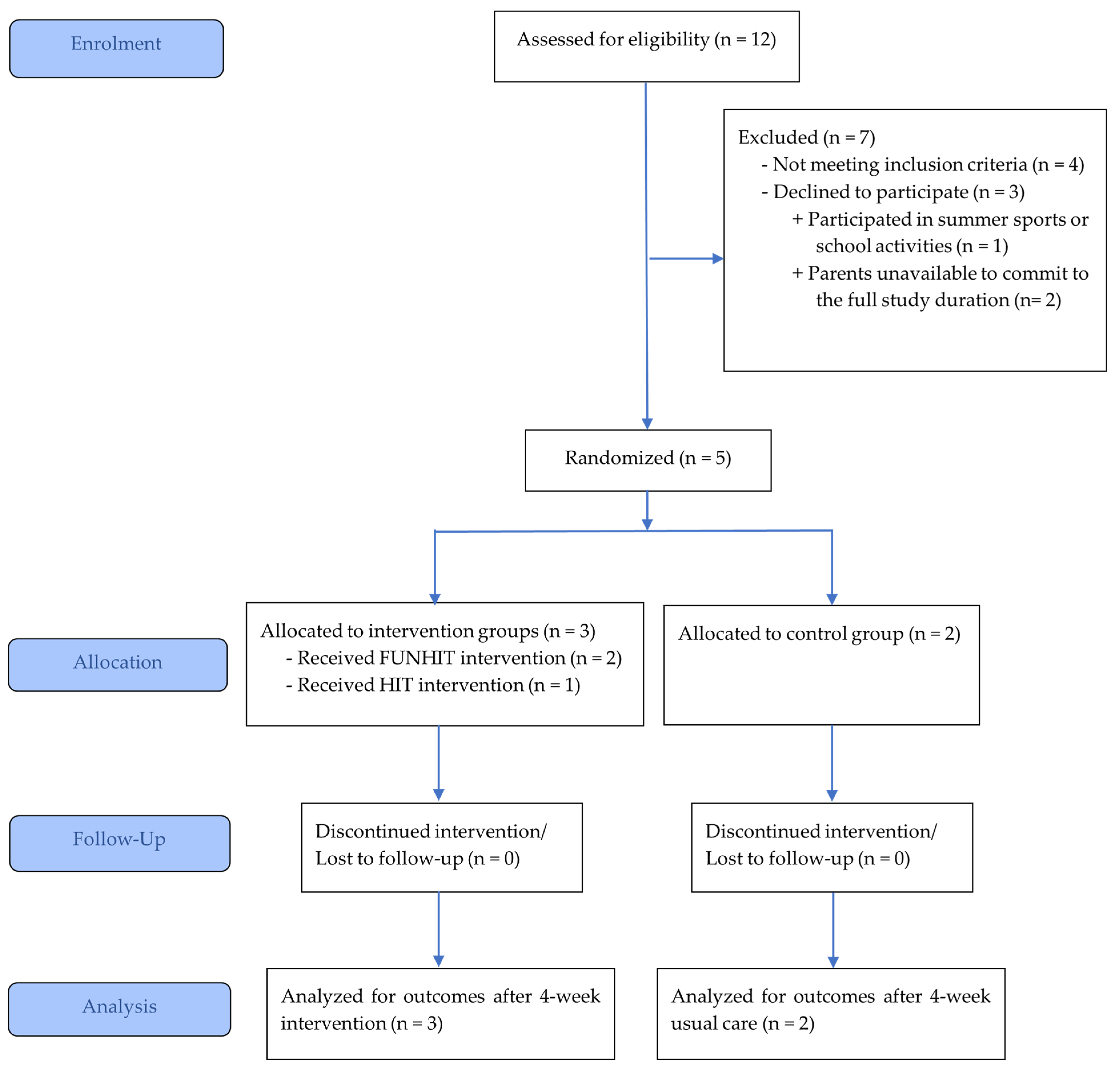

2.1. Study Design and Participant Recruitment

2.2. Participant Characteristics

2.3. Exercise Dose Determination

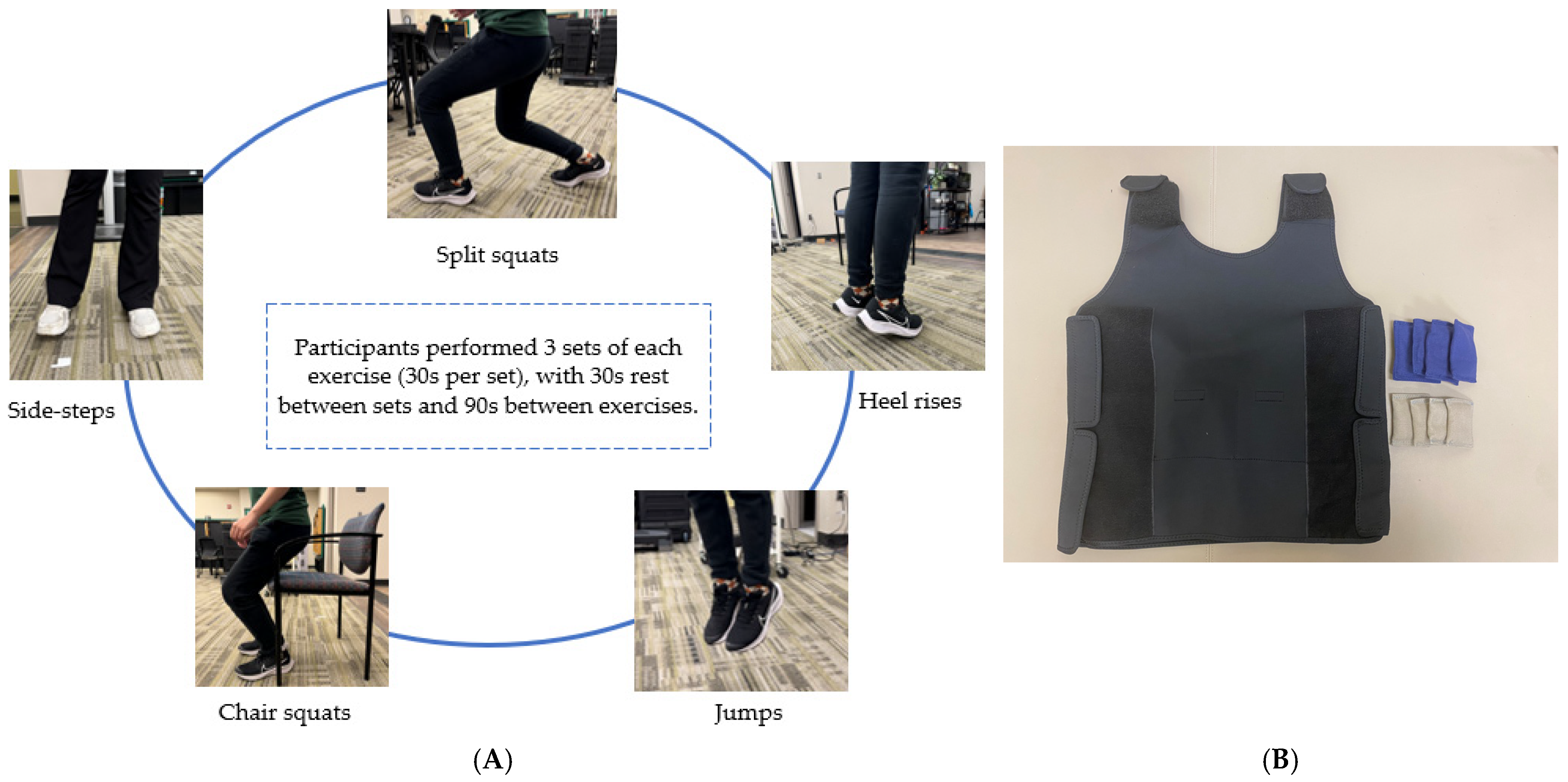

2.4. Exercise Intervention

2.5. Feasibility Metrics

2.6. Assessments

- The Four Square Step Test (FSST) utilized four canes arranged in a cross on the floor, forming four squares, where participants were instructed to step forward, sideways, and backward in a specific sequence as quickly as possible without touching the canes, with the time recorded in seconds using a stopwatch to assess dynamic balance and coordination [43].

- The Lateral Step-Up Test (LSUT) required participants to stand beside an adjustable step (height set at low level (~17 cm) and high level (~37 cm)) and step laterally onto it with one leg, fully extending the knee, then return to the starting position, repeating this for 20 s, with the number of completed steps counted to measure lower limb strength [44].

- The Timed Up and Go Test (TUG) involved participants rising from a standard chair, walking 3 m to a marked cone, turning 180 degrees, and returning to sit, with time recorded in seconds using a stopwatch to evaluate functional mobility [45].

- The TUG with counting backward required participants to count aloud by subtracting 3 from a random number between 20–80 while performing the standard TUG [46].

- The TUG with a full cup of water required participants to carry a full plastic cup of water (around 250 mL) while performing the standard TUG and not spilling the water [47].

- The Unrestrained Maximum Walking Speed Test employed a 6-m-long pressure-sensitive mat (ProtoKinetics Zeno™ Walkway Gait Analysis System; ProtoKinetics LLC, Havertown, PA, USA), where participants started two steps before and walked past the mat at their fastest safe speed, with the mat capturing spatiotemporal gait measures (such as speed (m/s), step length (cm), and cadence (steps/min)) to measure their functional mobility [48].

- The Restrained Maximum Walking Speed Test, on the same Zeno™ walkway system, required participants to start by standing on the mat and then walking at their fastest safe speed and stopping at a marked position on the mat near its endpoint [48].

- The PROMIS Physical Activity (PA) Questionnaire consists of 10 questions assessing the participant’s physical activity over the past 7 days. Responses are scored on a scale from 1 to 5 (1 = no days, 2 = 1 day, 3 = 2–3 days, 4 = 4–5 days, 5 = 6–7 days), with higher total scores indicating greater levels of physical activity during the previous week [49].

- The Pediatric Fear-of-Falling (FoF) Questionnaire includes 34 questions evaluating the participant’s fear of falling during various daily activities. Responses are rated on a scale from 0 to 2 (0 = never, 1 = sometimes, 2 = always) or marked as N/A (not applicable), with higher total scores indicating greater fear of falling [50].

- Due to the pilot and feasibility design of our study, we report our results of feasibility and treatment response metrics as absolute numbers. Mean and SD (Standard deviation) are reported for exercise dosage determination and progression. Treatment responses for the pre-post changes are reported as percentages.

3. Results

3.1. Feasibility Study

3.1.1. Process Metrics

3.1.2. Operational Feasibility

3.1.3. Scientific Evidence

3.2. Exercise Repetitions

3.3. Preliminary Data

4. Discussion

4.1. Feasibility

4.2. Preliminary Findings

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

Abbreviations

| CP | Cerebral palsy |

| SB | Spina bifida |

| HIT | High-Intensity Circuit Training |

| FUNHIT | Functionally Loaded High-Intensity Circuit Training |

| RPE FSST | Rating of perceived exertion Four Square Step Test |

| TUG | Timed Up and Go |

| LSUT | Lateral Step-Up Test |

| PA | Physical activity |

| FoF | Fear of Falling |

| GMFCS | Gross Motor Function Classification System |

| UAB | University of Alabama at Brimingham |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| N/A | Not applicable |

Appendix A

| Exercises | Descriptions |

|---|---|

Split squats | Participants begin in a split stance with one leg in front and the other behind hip width apart. Participants lower their hips until the back knee is almost touching the floor, then stand back up and switch legs. |

Countermovement jumps | Participants will stand upright with feet on the floor and hands on hips. They will bend their knees to a comfortable height quickly and then immediately take off vertically and get back to upright posture on landing back on the floor. |

Heel raise | Participants will raise their heels off the floor as high as possible while keeping their knees straight. Then, they will lower their heels slightly to touch the floor and raise the heel again. |

Chair squats | Participants will stand just in front of their chair, facing away from it. They will ensure their feet are shoulder-width apart and keep their spine neutral, with their head and chest raised. When they bend their knees and hips to lower their center of gravity down and up, they will engage their core. Participants will gently tap the chair with their buttocks without sitting down. Finally, they will drive their hips forward and up, returning to the starting position. |

Side steps | Participants will start off with their feet shoulder width-apart. They will be instructed to shuffle their feet out by taking their leg out sideways, one at a time, without moving the other leg. The other leg will start the movement only when the initiating leg has returned to the starting position. |

Appendix B

References

- Rosenbaum, P.; Paneth, N.; Leviton, A.; Goldstein, M.; Bax, M.; Damiano, D.; Dan, B.; Jacobsson, B. A report: The definition and classification of cerebral palsy April 2006. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. Suppl. 2007, 109, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Javed, K.; Daly, D.T. Neuroanatomy, Lower Motor Neuron Lesion. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, E.S.; Hu, D.A.; Zhang, L.; Qi, R.; Xu, C.; Mei, O.; Shen, G.; You, W.; Luo, C.; He, T.C.; et al. Spina bifida as a multifactorial birth defect: Risk factors and genetic underpinnings. Pediatr. Discov. 2025, 3, e2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opheim, A.; Jahnsen, R.; Olsson, E.; Stanghelle, J.K. Walking function, pain, and fatigue in adults with cerebral palsy: A 7-year follow-up study. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2009, 51, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, P.; McGinley, J. Gait function and decline in adults with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2014, 36, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendt, M.; Forslund, E.B.; Hagman, G.; Hultling, C.; Seiger, Å.; Franzén, E. Gait and dynamic balance in adults with spina bifida. Gait Posture 2022, 96, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bent, M.A.; Ciccodicola, E.M.; Rethlefsen, S.A.; Wren, T.A.L. Increased Asymmetry of Trunk, Pelvis, and Hip Motion during Gait in Ambulatory Children with Spina Bifida. Symmetry 2021, 13, 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, M.J.; Arpin, D.J.; Corr, B. Differences in the dynamic gait stability of children with cerebral palsy and typically developing children. Gait Posture 2012, 36, 600–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barja, S.; Le Roy, C.; Sepúlveda, C.; Guzmán, M.L.; Olivarez, M.; Figueroa, M.J. Obesity and cardio-metabolic risk factors among children and adolescents with cerebral palsy. Nutr. Hosp. 2020, 37, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortuna, R.J.; Holub, A.; Turk, M.A.; Meccarello, J.; Davidson, P.W. Health conditions, functional status and health care utilization in adults with cerebral palsy. Fam. Pract. 2018, 35, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurković, J.S.; Petković, P.; Tiosavljević, D.; Vojinović, R. Measurement of Bone Mineral Density in Children with Cerebral Palsy from an Ethical Issue to a Diagnostic Necessity. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 7282946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, I.; McIntyre, S.; Morgan, C.; Campbell, L.; Dark, L.; Morton, N.; Stumbles, E.; Wilson, S.A.; Goldsmith, S. A systematic review of interventions for children with cerebral palsy: State of the evidence. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2013, 55, 885–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, N.A.; Sanivarapu, R.R.; Osman, U.; Latha Kumar, A.; Sadagopan, A.; Mahmoud, A.; Begg, M.; Tarhuni, M.; Fotso, M.N.; Khan, S. Physical Therapy Interventions in Children with Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e43846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewar, R.; Love, S.; Johnston, L.M. Exercise interventions improve postural control in children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2015, 57, 504–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jefferies, M.; Peart, T.; Perrier, L.; Lauzon, A.; Munce, S. Psychological interventions for individuals with acquired brain injury, cerebral palsy, and spina bifida: A scoping review. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 782104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starowicz, J.; Cassidy, C.; Brunton, L. Health concerns of adolescents and adults with spina bifida. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 745814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Committee on the Neurobiological and Socio-behavioral Science of Adolescent Development and Its Applications. Adolescent Development. In The Promise of Adolescence: Realizing Opportunity for All Youth; Backes, E.B., Ed.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- INSERM Collective Expertise Centre. INSERM Collective Expert Reports. In Growth and Puberty Secular Trends, Environmental and Genetic Factors; Institut National de la Danté et de la Recherche Médicale: Paris, France, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- El Shemy, S.A. Effect of Treadmill Training with Eyes Open and Closed on Knee Proprioception, Functional Balance and Mobility in Children with Spastic Diplegia. Ann. Rehabil. Med. 2018, 42, 854–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnaggar, R.K.; Alhowimel, A.; Alotaibi, M.; Abdrabo, M.S.; Elfakharany, M.S. Exploring Temporospatial Gait Asymmetry, Dynamic Balance, and Locomotor Capacity After a 12-Week Split-Belt Treadmill Training in Adolescents with Unilateral Cerebral Palsy: A Randomized Clinical Study. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2023, 43, 660–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Song, S.; Lee, D.; Lee, K.; Lee, G. Effects of Kinect Video Game Training on Lower Extremity Motor Function, Balance, and Gait in Adolescents with Spastic Diplegia Cerebral Palsy: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Dev. Neurorehabilit. 2021, 24, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groot, J.F.d.; Takken, T.; Brussel, M.v.; Gooskens, R.; Schoenmakers, M.; Versteeg, C.; Vanhees, L.; Helders, P. Randomized controlled study of home-based treadmill training for ambulatory children with spina bifida. Neurorehabilit. Neural Repair. 2011, 25, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, I.; Pinto, S.M.; Virgens Chagas, D.d.; Dos Santos, J.L.P.; Sousa Oliveira, T.d.; Batista, L.A. Robotic gait training for individuals with cerebral palsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2017, 98, 2332–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funderburg, S.E.; Josephson, H.E.; Price, A.A.; Russo, M.A.; Case, L.E. Interventions for Gait Training in Children With Spinal Cord Impairments: A Scoping Review. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2017, 9, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowersock, C.D.; Tagoe, E.A.; Hopkins, S.; Fang, S.; Lerner, Z.F. Differential and Adjustable Stiffness Leaf Spring Ankle Foot Orthoses Enhance Gait Propulsion and Task Versatility in Cerebral Palsy. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2025, 53, 2459–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Shen, Q.; Huang, M.; Zhou, H. Factors associated with caregiver burden among family caregivers of children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e065215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadighian, M.J.; Allen, I.E.; Quanstrom, K.; Breyer, B.N.; Suskind, A.M.; Baradaran, N.; Copp, H.L.; Hampson, L.A. Caregiver burden among those caring for patients with spina bifida. Urology 2021, 153, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barros, A.L.O.; de Gutierrez, G.M.; Barros, A.O.; Santos, M. Quality of life and burden of caregivers of children and adolescents with disabilities. Spec. Care Dent. 2019, 39, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schranz, C.; Kruse, A.; Belohlavek, T.; Steinwender, G.; Tilp, M.; Pieber, T.; Svehlik, M. Does Home-Based Progressive Resistance or High-Intensity Circuit Training Improve Strength, Function, Activity or Participation in Children with Cerebral Palsy? Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2018, 99, 2457–2464.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauglo, R.; Vik, T.; Lamvik, T.; Stensvold, D.; Finbråten, A.-K.; Moholdt, T. High-intensity interval training to improve fitness in children with cerebral palsy. BMJ Open Sport. Exerc. Med. 2016, 2, e000111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnaggar, R.K.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Azab, A.R.; Alrawaili, S.M.; Alghadier, M.; Alotaibi, M.A.; Alhowimel, A.S.; Abdrabo, M.S.; Elbanna, M.F.; Aboeleneen, A.M.; et al. Optimization of Postural Control, Balance, and Mobility in Children with Cerebral Palsy: A Randomized Comparative Analysis of Independent and Integrated Effects of Pilates and Plyometrics. Children 2024, 11, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchheit, M.; Laursen, P.B. High-intensity interval training, solutions to the programming puzzle. Part II: Anaerobic energy, neuromuscular load and practical applications. Sports Med. 2013, 43, 927–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, N.F.; Dodd, K.J.; Damiano, D.L. Progressive Resistance Exercise in Physical Therapy: A Summary of Systematic Reviews. Phys. Ther. 2005, 85, 1208–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholtes, V.A.; Becher, J.G.; Comuth, A.; Dekkers, H.; Van Dijk, L.; Dallmeijer, A.J. Effectiveness of functional progressive resistance exercise strength training on muscle strength and mobility in children with cerebral palsy: A randomized controlled trial. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2010, 52, e107–e113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanssen, B.; Peeters, N.; De Beukelaer, N.; Vannerom, A.; Peeters, L.; Molenaers, G.; Van Campenhout, A.; Deschepper, E.; Van den Broeck, C.; Desloovere, K. Progressive resistance training for children with cerebral palsy: A randomized controlled trial evaluating the effects on muscle strength and morphology. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 911162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillett, J.G.; Lichtwark, G.A.; Boyd, R.N.; Barber, L.A. Functional Anaerobic and Strength Training in Young Adults with Cerebral Palsy. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2018, 50, 1549–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, H.F.; Liu, Y.C.; Liu, W.Y.; Lin, Y.T. Effectiveness of loaded sit-to-stand resistance exercise for children with mild spastic diplegia: A randomized clinical trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2007, 88, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallmeijer, A.J.; Rameckers, E.A.; Houdijk, H.; de Groot, S.; Scholtes, V.A.; Becher, J.G. Isometric muscle strength and mobility capacity in children with cerebral palsy. Disabil. Rehabil. 2017, 39, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Ma, M.; Liu, H.; Wei, X.; Chen, X. Effects of step lengths on biomechanical characteristics of lower extremity during split squat movement. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1277493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, M.; Higuchi, Y.; Yonetsu, R.; Kitajima, H. Plantarflexor training affects propulsive force generation during gait in children with spastic hemiplegic cerebral palsy: A pilot study. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2015, 27, 1283–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.A.; Engsberg, J.R. Relationships between spasticity, strength, gait, and the GMFM-66 in persons with spastic diplegia cerebral palsy. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2007, 88, 1114–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Carrillo, E.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Izquierdo, M.; Elnaggar, R.K.; Afonso, J.; Penailillo, L.; Araneda, R.; Ebner-Karestinos, D.; Granacher, U. Effects of Therapies Involving Plyometric-Jump Training on Physical Fitness of Youth with Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Sports 2024, 12, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandong, A.N.; Madriaga, G.O.; Gorgon, E.J. Reliability and validity of the Four Square Step Test in children with cerebral palsy and Down syndrome. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2015, 47, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysagis, N.; Skordilis, E.K.; Tsiganos, G.; Koutsouki, D. Validity evidence of the Lateral Step Up (LSU) test for adolescents with spastic cerebral palsy. Disabil. Rehabil. 2013, 35, 875–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, H.; Martin, K.; Combs-Miller, S.; Heathcock, J.C. Reliability and Responsiveness of the Timed Up and Go Test in Children with Cerebral Palsy. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2016, 28, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cekok, K.; Kahraman, T.; Duran, G.; Donmez Colakoglu, B.; Yener, G.; Yerlikaya, D.; Genc, A. Timed Up and Go Test with a Cognitive Task: Correlations with Neuropsychological Measures in People with Parkinson’s Disease. Cureus 2020, 12, e10604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shumway-Cook, A.; Brauer, S.; Woollacott, M. Predicting the probability for falls in community-dwelling older adults using the Timed Up & Go Test. Phys. Ther. 2000, 80, 896–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorgensen, A.; McManigal, M.; Post, A.; Werner, D.; Wichman, C.; Tao, M.; Wellsandt, E. Reliability of an Instrumented Pressure Walkway for Measuring Walking and Running Characteristics in Young, Athletic Individuals. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2024, 19, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, C.A.; Bevans, K.B.; Becker, B.D.; Teneralli, R.; Forrest, C.B. Development of the PROMIS Pediatric Physical Activity Item Banks. Phys. Ther. 2020, 100, 1393–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipek, C.; Yilmaz, O.; Karaduman, A.; Alemdaroglu-Gurbuz, I. Development of a questionnaire to assess fear of falling in children with neuromuscular diseases. J. Pediatr. Orthop. B 2021, 30, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, C.P.; Nápoles, A.M.; Dohan, D.; Shelley Hwang, E.; Melisko, M.; Nickleach, D.; Quinn, J.A.; Haas, J. Clinical trial discussion, referral, and recruitment: Physician, patient, and system factors. Cancer Causes Control 2013, 24, 979–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, B.; Vogtle, L.; Young, R.; Craig, M.; Kim, Y.; Gowey, M.; Swanson-Kimani, E.; Davis, D.; Rimmer, J.H. Telehealth Movement-to-Music to Increase Physical Activity Participation Among Adolescents with Cerebral Palsy: Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Form. Res. 2022, 6, e36049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niyonsenga, J.; Uwingeneye, L.; Musabyemariya, I.; Sagahutu, J.B.; Cavallini, F.; Caricati, L.; Eugene, R.; Mutabaruka, J.; Jansen, S.; Monacelli, N. The psychosocial determinants of adherence to home-based rehabilitation strategies in parents of children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0305432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.W.; Williams, S.A.; Gucciardi, D.F.; Bear, N.; Gibson, N. Can an online exercise prescription tool improve adherence to home exercise programmes in children with cerebral palsy and other neurodevelopmental disabilities? A randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e040108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannocci, A.; D’Egidio, V.; Backhaus, I.; Federici, A.; Sinopoli, A.; Ramirez Varela, A.; Villari, P.; La Torre, G. Are There Effective Interventions to Increase Physical Activity in Children and Young People? An Umbrella Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leahy, A.A.; Robinson, K.; Eather, N.; Smith, J.J.; Hillman, C.H.; Beacroft, S.; Mazzoli, E.; Lubans, D.R. School Physical Activity Interventions for Children and Adolescents with Disability: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Effects on Academic, Cognitive, and Mental Health Outcomes. J. Phys. Act. Health 2025, 22, 1064–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minghetti, A.; Widmer, M.; Viehweger, E.; Roth, R.; Gysin, R.; Keller, M. Translating scientific recommendations into reality: A feasibility study using group-based high-intensity functional exercise training in adolescents with cerebral palsy. Disabil. Rehabil. 2024, 46, 4787–4796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mduluza, T.; Midzi, N.; Duruza, D.; Ndebele, P. Study participants incentives, compensation and reimbursement in resource-constrained settings. BMC Med. Ethics 2013, 14, S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J.M.; Lavelle, G.; Theis, N.; Noorkoiv, M.; Kilbride, C.; Korff, T.; Baltzopoulos, V.; Shortland, A.; Levin, W.; Team, T.S.T. Progressive resistance training for adolescents with cerebral palsy: The STAR randomized controlled trial. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2020, 62, 1283–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am. Psychol. 1982, 37, 122–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, B.; Lee, E.; Wagatsuma, M.; Frey, G.; Stanish, H.; Jung, T.; Rimmer, J.H. Research Trends and Recommendations for Physical Activity Interventions Among Children and Youth with Disabilities: A Review of Reviews. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 2020, 37, 211–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, T.J.; Riek, S.; Carson, R.G. Neural adaptations to resistance training: Implications for movement control. Sports Med. 2001, 31, 829–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.J.; Lee, B.H. Effect of Functional Progressive Resistance Exercise on Lower Extremity Structure, Muscle Tone, Dynamic Balance and Functional Ability in Children with Spastic Cerebral Palsy. Children 2020, 7, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, A.M.; Powell, L.E.; Maki, B.E.; Holliday, P.J.; Brawley, L.R.; Sherk, W. Psychological indicators of balance confidence: Relationship to actual and perceived abilities. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 1996, 51, M37–M43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, F.; Engel, F.A.; Reimers, A.K. Compensation or Displacement of Physical Activity in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Empirical Studies. Children 2022, 9, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ID | Age (y) | Diagnosis | Group | Sex |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P01 | 20.2 | CP | FUNHIT | Male |

| P02 | 14.1 | SB | FUNHIT | Female |

| P03 | 14.8 | SB | HIT | Male |

| P04 | 15.6 | SB | Control | Male |

| P05 | 14.2 | SB | Control | Male |

| Metric | Outcome | Assessment Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Process metrics: evaluate participant recruitment, retention, and adherence | 1. Participant screening and enrollment metrics 2. Participant completion rate 3. Compliance rate | 1. Number of individuals screened, found eligible, and successfully enrolled. 2. Refusal rate and documented reasons for non-participation. 3. Completion rate for baseline/pre-intervention assessments. 4. Retention rate through the 4-week intervention period. 5. Overall study completion rate, based on the post-intervention assessment. |

| Operational metrics: evaluate the time and financial resources required for the study, as well as the data management and safety reporting procedures | 1. Time spent on recruitment, pre/post assessment, and intervention phases 2. Time and effort for participant data collection and personnel data processing. 3. Financial resources necessary to conduct the study | 1. Duration of participant recruitment (from initial contact to enrollment) (days) 2. Duration of eligibility screening (minutes) 3. Time spent on the pre-assessment phases (hours) 4. Time spent on the post-assessment phase (hours) 5. Time spent on the intervention phase (hours) 6. Time for participants to complete FoF Questionnaire (minutes) 7. Time for participants to complete PA Questionnaire (minutes) 8. Personnel time to download and process Zeno walkway path data (hours) 9. Total cost (USD) |

| Clinical metrics: evaluate safety, burden, and treatment effect | 1. Adverse events, serious adverse events, and clinical emergencies 2. Participants’ ability to adhere to the prescribed intervention dosage and repetitions throughout the study 3. Intervention effects measured via:

| 1. Number of adverse events, serious adverse events, and clinical emergencies 2. Assessment of participants’ adherence to the prescribed intervention frequency, duration, and repetitions. 3. Intervention responses were assessed and changes in dynamic balance and muscle strength outcome variables |

| Exercise | ID | Pre-Intervention | Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline 1 (Mean ± SD) | Baseline 2 (Mean ± SD) | Day 1 (Mean ± SD) | Day 2 (Mean ± SD) | Day 1 (Mean ± SD) | Day 2 (Mean ± SD) | Day 1 (Mean ± SD) | Day 2 (Mean ± SD) | Day 1 (Mean ± SD) | Day 2 (Mean ± SD) | ||

| Chair squats | P01 | 16.67 ± 0.58 | 16.00 ± 0 | 17.00 ± 1 | 18.00 ± 0 | 20.00 ± 1.73 | 20.67 ± 0.58 | 22.00 ± 0 | 22.00 ± 0 | 23.33 ± 1.15 | 26.67 ± 0.58 |

| P02 | 13.67 ± 0.58 | 14.00 ± 0 | 16.00 ± 0 | 16.00 ± 0 | 17.33 ± 1.15 | 18.00 ± 0 | 19.33 ± 1.15 | 20.00 ± 0 | 21.33 ± 1.15 | 22.00 ± 0 | |

| P03 | 9.67 ± 1.53 | 11.33 ± 1.15 | 12.00 ± 0 | 12.00 ± 0 | 13.33 ± 1.15 | 14.00 ± 0 | 15.33 ± 1.15 | 16.00 ± 0 | 17.33 ± 1.15 | 18.00 ± 0 | |

| Split squats | P01 | 13.67 ± 1.53 | 14.00 ± 0 | 15.67 ± 0.58 | 15.00 ± 1 | 15.00 ± 0 | 15.33 ± 0.58 | 16.33 ± 1.15 | 17.00 ± 0 | 18.33 ± 1.15 | 19.00 ± 0 |

| P02 | 14.67 ± 2.31 | 15.00 ± 1.73 | 14.33 ± 1.15 | 15.00 ± 0 | 16.33 ± 1.15 | 17.00 ± 0 | 18.33 ± 1.15 | 19.00 ± 0 | 20.33 ± 1.15 | 21.00 ± 0 | |

| P03 | 15.00 ± 4.58 | 16.00 ± 0 | 16.00 ± 0 | 16.00 ± 0 | 17.33 ± 1.15 | 18.00 ± 0 | 19.33 ± 1.15 | 20.00 ± 0 | 21.33 ± 1.15 | 22.00 ± 0 | |

| Side steps | P01 | 35.00 ± 5.57 | 36.00 ± 0 | 38.00 ± 0 | 37.67 ± 0.58 | 39.33 ± 1.15 | 36.67 ± 1.15 | 37.33 ± 0.58 | 38.67 ± 1.15 | 38.67 ± 1.15 | 40.00 ± 3.46 |

| P02 | 37.67 ± 2.31 | 34.33 ± 2.08 | 34.00 ± 0 | 34.00 ± 0 | 35.33 ± 1.15 | 36.00 ± 0 | 37.33 ± 1.15 | 38.00 ± 0 | 39.33 ± 1.15 | 40.00 ± 0 | |

| P03 | 17.00 ± 2.65 | 16.67 ± 1.53 | 17.67 ± 1.15 | 17.00 ± 0 | 18.33 ± 1.15 | 19.00 ± 0 | 20.33 ± 1.15 | 21.00 ± 0 | 22.33 ± 1.15 | 23.00 ± 0 | |

| Jumps | P01 | 11.67 ± 0.58 | 11.00 ± 0 | 12.33 ± 0.58 | 13.00 ± 0 | 13.00 ± 0 | 15.00 ± 0 | 15.00 ± 0 | 17.00 ± 0 | 15.67 ± 1.15 | 19.00 ± 0 |

| P02 | 27.33 ± 3.21 | 22.67 ± 0.58 | 25.00 ± 0 | 25.00 ± 0 | 26.33 ± 1.15 | 27.00 ± 0 | 28.33 ± 1.15 | 29.00 ± 0 | 30.33 ± 1.15 | 31.00 ± 0 | |

| P03 | 22.00 ± 5.20 | 25.00 ± 0 | 25.00 ± 0 | 25.00 ± 0 | 26.33 ± 1.15 | 27.00 ± 0 | 28.33 ± 1.15 | 29.00 ± 0 | 30.33 ± 1.15 | 31.33 ± 0.58 | |

| Heel raise | P01 | 22.00 ± 1 | 21.00 ± 0 | 22.00 ± 1 | 22.00 ± 1 | 22.33 ± 1.15 | 22.67 ± 0.58 | 23.67 ± 1.15 | 25.00 ± 0 | 25.00 ± 2 | 26.00 ± 1.73 |

| P02 | 18.67 ± 2.08 | 19.00 ± 2.65 | 19.33 ± 1.15 | 29.67 ± 0.58 | 31.33 ± 1.15 | 30.67 ± 1.53 | 33.33 ± 1.15 | 34.00 ± 0 | 35.00 ± 1.73 | 34.67 ± 1.15 | |

| P03 | 25.00 ± 2.65 | 23.67 ± 1.53 | 24.00 ± 0 | 24.00 ± 0 | 25.33 ± 1.15 | 26.00 ± 0 | 27.33 ± 1.15 | 28.00 ± 0 | 29.33 ± 1.15 | 31.00 ± 0 | |

| Exercise | ID | % Improvement from Baseline 1 to Week 4 Day 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Chair squats | P01 | 60.00% |

| P02 | 60.98% | |

| P03 | 86.21% | |

| Average: 69.06% | ||

| Split squats | P01 | 39.02% |

| P02 | 43.18% | |

| P03 | 46.67% | |

| Average: 42.96% | ||

| Side steps | P01 | 14.29% |

| P02 | 6.19% | |

| P03 | 35.29% | |

| Average: 18.59% | ||

| Jumps | P01 | 62.86% |

| P02 | 13.41% | |

| P03 | 42.42% | |

| Average: 39.57% | ||

| Heel raise | P01 | 18.18% |

| P02 | 85.71% | |

| P03 | 24.00% | |

| Average: 42.63% | ||

| ID | Group | Unrestrained Maximum Walking Speed (cm/s) | Delta | Percentage Change | Restrained Maximum Walking Speed (cm/s) | Delta | Percentage Change | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline 2 | Posttest | Baseline 2 | Posttest | ||||||

| P01 | FunHIT | 130.029 | 140.53 | 10.501 | 8% | 57.952 | 75.19 | 17.238 | 30% |

| P02 | FunHIT | 120.602 | 135.522 | 14.92 | 12% | 75.294 | 65.884 | −9.41 | −12% |

| P03 | HIT | 71.397 | 72.957 | 1.56 | 2% | 41.2 | 47.121 | 5.921 | 14% |

| P04 | Control | 209.874 | 210.985 | 1.111 | 1% | 92.292 | 101.862 | 9.57 | 10% |

| P05 | Control | 217.511 | 239.697 | 22.186 | 10% | 86.453 | 83.469 | −2.984 | −3% |

| ID | Group | LSUT at Low Level (Step Counts) | Delta | Percentage Change | LSUT at High Level (Step Counts) | Delta | Percentage Change | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline 2 | Posttest | Baseline 2 | Posttest | ||||||

| P01 | FunHIT | 11 | 14 | 3 | 27% | 10 | 13 | 3 | 30% |

| P02 | FunHIT | 9 | 12 | 3 | 33% | 9 | 11 | 2 | 22% |

| P03 | HIT | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0% | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0% |

| P04 | Control | 22 | 26 | 4 | 18% | 23 | 24 | 1 | 4% |

| P05 | Control | 21 | 26 | 5 | 24% | 20 | 24 | 4 | 20% |

| ID | Group | FSST (Seconds) | Delta | Percentage Change | TUG (Seconds) | Delta | Percentage Change | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline 2 | Posttest | Baseline 2 | Posttest | ||||||

| P01 | FunHIT | 11.14 | 7.89 | −3.25 | −29% | 8.92 | 8.6 | −0.32 | −4% |

| P02 | FunHIT | 8.7 | 7.39 | −1.31 | −15% | 10.23 | 9.85 | −0.38 | −4% |

| P03 | HIT | 29.73 | 20.73 | −9 | −30% | 14.64 | 12.96 | −1.68 | −11% |

| P04 | Control | 5.56 | 5.67 | 0.11 | 2% | 9.9 | 8.92 | −0.98 | −10% |

| P05 | Control | 6.23 | 5.55 | −0.68 | −11% | 8.44 | 8.25 | −0.19 | −2% |

| ID | Group | TUG with Counting (Seconds) | Delta | Percentage Change | TUG with Holding a Cup (Seconds) | Delta | Percentage Change | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline 2 | Posttest | Baseline 2 | Posttest | ||||||

| P01 | FunHIT | 13.32 | 15.29 | 1.97 | 15% | 18.66 | 15.87 | −2.79 | −15% |

| P02 | FunHIT | 15.84 | 10.33 | −5.51 | −35% | 15.42 | 15.09 | −0.33 | −2% |

| P03 | HIT | 24.73 | 14.93 | −9.8 | −40% | 22.07 | 18.23 | −3.84 | −17% |

| P04 | Control | 10.02 | 10.03 | 0.01 | 0% | 12.55 | 11.87 | −0.68 | −5% |

| P05 | Control | 11.68 | 9.38 | −2.3 | −20% | 10.33 | 10.09 | −0.24 | −2% |

| ID | Group | FoF Questionnaire (Score) | Delta | Percentage Change | PA Questionnaire (Score) | Delta | Percentage Change | ||

| Baseline 2 | Posttest | Baseline 2 | Posttest | ||||||

| P01 | FunHIT | 19 | 11 | −8 | −42% | 33 | 30 | −3 | −9% |

| P02 | FunHIT | 9 | 14 | 5 | 56% | 22 | 31 | 9 | 41% |

| P03 | HIT | 10 | 12 | 2 | 20% | 35 | 27 | −8 | −23% |

| P04 | Control | 9 | 8 | −1 | −11% | 32 | 37 | 5 | 16% |

| P05 | Control | 22 | 22 | 0 | 0% | 34 | 36 | 2 | 6% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Quach, P.T.M.; Fisher, G.; Lai, B.; Modlesky, C.M.; Hurt, C.P.; Bowersock, C.D.; Boolani, A.; Singh, H. Feasibility and Preliminary Response of a Novel Training Program on Mobility Parameters in Adolescents with Movement Disorders. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3251. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243251

Quach PTM, Fisher G, Lai B, Modlesky CM, Hurt CP, Bowersock CD, Boolani A, Singh H. Feasibility and Preliminary Response of a Novel Training Program on Mobility Parameters in Adolescents with Movement Disorders. Healthcare. 2025; 13(24):3251. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243251

Chicago/Turabian StyleQuach, Phuong T. M., Gordon Fisher, Byron Lai, Christopher M. Modlesky, Christopher P. Hurt, Collin D. Bowersock, Ali Boolani, and Harshvardhan Singh. 2025. "Feasibility and Preliminary Response of a Novel Training Program on Mobility Parameters in Adolescents with Movement Disorders" Healthcare 13, no. 24: 3251. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243251

APA StyleQuach, P. T. M., Fisher, G., Lai, B., Modlesky, C. M., Hurt, C. P., Bowersock, C. D., Boolani, A., & Singh, H. (2025). Feasibility and Preliminary Response of a Novel Training Program on Mobility Parameters in Adolescents with Movement Disorders. Healthcare, 13(24), 3251. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243251