Economic Analyses of COVID-19 Interventions: A Narrative Review of Global Evidence

Highlights

- Vaccination—especially with mRNA vaccines—is consistently the most cost-effective COVID-19 intervention, often cost-saving in high-risk populations.

- Combined strategies integrating vaccination, testing, and targeted social distancing yield superior health and economic outcomes compared with single-measure approaches.

- Early, targeted, and layered implementation should guide future pandemic response and preparedness strategies to maximize economic and societal value.

- Incorporating equity, indirect effects (e.g., productivity, education), and standardized methodological frameworks will strengthen decision-making and resource prioritization in future public health emergencies.

Abstract

1. Introduction

State of the Art

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Setting: Conducted in healthcare, community, or educational environments (e.g., hospitals, long-term care facilities, schools).

- Interventions: Addressed one or more of the following—vaccination (including booster programs); testing and screening strategies (PCR, antigen, or hybrid approaches); non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) such as social distancing and school closures; or combined multicomponent strategies.

- Perspective: Economic analyses conducted from a healthcare payer/provider or societal perspective.

- Outcomes: Reported incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs), net monetary benefit (NMB), or other quantifiable cost-effectiveness metrics (e.g., cases, hospitalizations, or deaths averted).

- Publication characteristics: English-language, peer-reviewed journal articles published between January 2020 and September 2025.

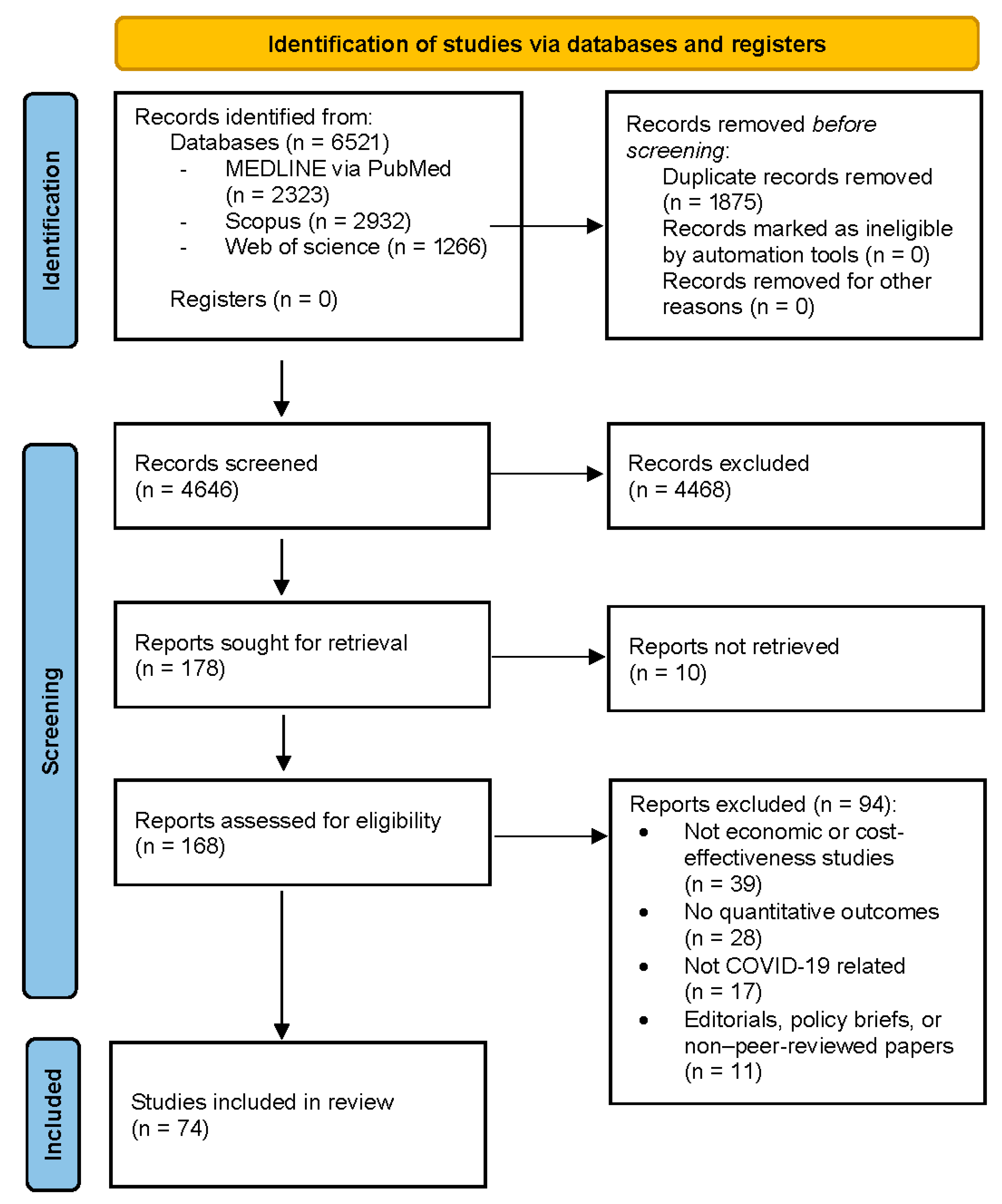

2.3. Screening and Data Extraction

2.4. Appraisal of Included Studies

- Study perspective and comparators—whether the chosen perspective (healthcare, societal) and comparator were clearly justified.

- Analytical framework—appropriateness of model type or trial design and transparency of assumptions.

- Time horizon and discounting—consistency with the intervention’s expected duration of benefit.

- Cost and outcome data sources—transparency and local relevance.

- Handling of uncertainty—inclusion of deterministic or probabilistic sensitivity analyses.

- Equity and distributional analysis—whether subgroup or DCEA/ECEA frameworks were applied.

- Validation and calibration (for models)—evidence of internal or external validation.

- Reporting quality—explicit alignment with CHEERS 2022 items.

3. Results

3.1. Cost-Effectiveness Variations Across Different Healthcare Settings

3.2. Cost-Effectiveness Implications of Different Vaccine Types and Dosing Strategies (Primary Series, Boosters) in High-Risk Versus Low-Risk Populations Within Each Setting

3.3. The Impact of Intervention Timing (Early vs. Late Implementation) on Cost-Effectiveness, Especially for Social Distancing and Testing Strategies

3.4. The Phase of the Epidemic (e.g., Surge vs. Low Transmission) and the Relative Cost-Effectiveness Alteration of Routine Testing and Social Distancing in Schools and Long-Term Care Facilities

3.5. Comparative Cost-Effectiveness of Vaccine Platforms and Dosing Strategies by Population Risk and Setting

3.5.1. Overview of Cost-Effectiveness in Adult Vaccination

3.5.2. Vaccine Types and Dosing Strategies

3.5.3. High-Risk vs. Low-Risk Populations

3.5.4. Healthcare Setting Considerations

3.5.5. Sensitivity Analyses and Key Drivers

3.5.6. Gaps and Limitations

3.5.7. Lessons from Adult Immunization Economics

3.6. Compliance Rates and Population Heterogeneity (Age, Comorbidities, Socioeconomic Status) Effect on the Cost-Effectiveness of Interventions

3.7. The Role of Combined Interventions (e.g., Vaccination Plus Targeted Testing and Partial Social Distancing) Compared to Single Strategies in Maximizing Cost-Effectiveness

3.8. The Impact of Non-Health Impacts and Distributional Effects (e.g., Equity, Access Disparities) in Modifying the Assessment of Cost-Effectiveness for These Interventions

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACIP | Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices |

| CEAs | Cost-Effectiveness Analyses |

| CHEERS | Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| DCEA | Distributional Cost-Effectiveness Analysis |

| ECEA | Extended Cost-Effectiveness Analysis |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| ICER | Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratio |

| HTA | Health Technology Assessment |

| HTCI | Hospital-based Treatment and Care Improvements |

| LMICs | Low- and Middle-Income Countries |

| mRNA | Messenger RNA |

| NMB | Net Monetary Benefit |

| NMIs | Non-Medical Interventions |

| NPIs | Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions |

| NNV | Number Needed to Vaccinate |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| QALY | Quality-Adjusted Life Year |

| RWE | Real-World Evidence |

| VE | Vaccine Effectiveness |

Appendix A. Database Search Strategies

| Database | Search String (Simplified) | Limits Applied | Records Retrieved |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed (MEDLINE) | ((COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV-2 OR coronavirus) AND (“cost-effectiveness” OR “economic evaluation” OR “budget impact”) AND (vaccination OR testing OR “non-pharmaceutical interventions” OR “social distancing”)) | English language; humans; journal articles; 2020–2025 | 2323 |

| Scopus (Elsevier) | TITLE-ABS-KEY((COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV-2 OR coronavirus) AND (“cost-effectiveness” OR “economic evaluation” OR “budget impact”) AND (vaccination OR testing OR “non-pharmaceutical interventions” OR “social distancing”)) AND PUBYEAR > 2019 AND PUBYEAR < 2026 AND (LIMIT-TO(LANGUAGE,”English”)) | Article/Review; English; 2020–2025 | 2932 |

| Web of Science (Core Collection) | TS = ((COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV-2 OR coronavirus) AND (“cost-effectiveness” OR “economic evaluation” OR “budget impact”) AND (vaccination OR testing OR “non-pharmaceutical interventions” OR “social distancing”))) Refined by: DOCUMENT TYPES (ARTICLE OR REVIEW) AND LANGUAGES (ENGLISH) Timespan: 2020–2025 Indexes: SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, ESCI | Article/Review; English; 2020–2025 | 1266 |

References

- Faramarzi, A.; Norouzi, S.; Dehdarirad, H.; Aghlmand, S.; Yusefzadeh, H.; Javan-Noughabi, J. The Global Economic Burden of COVID-19 Disease: A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Syst. Rev. 2024, 13, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Wang, H.; Li, X.; Zheng, W.; Ye, S.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, J.; Pennington, M. Economic Burden of COVID-19, China, January–March 2020: A Cost-of-Illness Study. Bull. World Health Organ. 2021, 99, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha-Filho, C.R.; Martins, J.W.L.; Lucchetta, R.C.; Ramalho, G.S.; Trevisani, G.F.M.; da Rocha, A.P.; Pinto, A.C.P.N.; Reis, F.S.A.; Ferla, L.J.; Mastroianni, P.C.; et al. Hospitalization Costs of Coronaviruses Diseases in Upper-Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanerva, M.; Rautava, K.; Kurvinen, T.; Marttila, H.; Finnilä, T.; Rantakokko-Jalava, K.; Pietilä, M.; Mustonen, P.; Kortelainen, M. Economic Impact and Disease Burden of COVID-19 in a Tertiary Care Hospital: A Three-Year Analysis. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0323200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, M.K.; Kronborg, C.; Fasterholdt, I.; Kidholm, K. Economic Evaluations of Interventions Against Viral Pandemics: A Scoping Review. Public Health 2022, 208, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandepitte, S.; Alleman, T.; Nopens, I.; Baetens, J.; Coenen, S.; De Smedt, D. Cost-Effectiveness of COVID-19 Policy Measures: A Systematic Review. Value Health 2021, 24, 1551–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezapour, A.; Souresrafil, A.; Peighambari, M.M.; Heidarali, M.; Tashakori-Miyanroudi, M. Economic Evaluation of Programs Against COVID-19: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 85, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podolsky, M.I.; Present, I.; Neumann, P.J.; Kim, D.D. A Systematic Review of Economic Evaluations of COVID-19 Interventions: Considerations of Non-Health Impacts and Distributional Issues. Value Health 2022, 25, 1298–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgenstern, C.; Laydon, D.J.; Whittaker, C.; Mishra, S.; Haw, D.; Bhatt, S.; Ferguson, N.M. The Interaction of Disease Transmission, Mortality, and Economic Output Over the First Two Years of the COVID-19 Pandemic. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0301785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Vullikanti, A.; Santos, J.; Venkatramanan, S.; Hoops, S.; Mortveit, H.; Lewis, B.; You, W.; Eubank, S.; Marathe, M.; et al. Epidemiological and Economic Impact of COVID-19 in the U.S. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gros, C.; Valenti, R.; Schneider, L.; Valenti, K.; Gros, D. Containment Efficiency and Control Strategies for the Corona Pandemic Costs. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Porritt, K.; Pilla, B.; Jordan, Z. (Eds.) JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Husereau, D.; Drummond, M.; Augustovski, F.; de Bekker-Grob, E.; Briggs, A.H.; Carswell, C.; Caulley, L.; Chaiyakunapruk, N.; Greenberg, D.; Loder, E.; et al. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards 2022 (CHEERS 2022) Statement: Updated Reporting Guidance for Health Economic Evaluations. BMJ 2022, 376, e067975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philips, Z.; Ginnelly, L.; Sculpher, M.; Claxton, K.; Golder, S.; Riemsma, R.; Woolacoot, N.; Glanville, J. Review of Guidelines for Good Practice in Decision-Analytic Modelling in Health Technology Assessment. Health Technol. Assess. 2004, 8, iii–iv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotakopoulos, L.; Moulia, D.L.; Godfrey, M.; Link-Gelles, R.; Roper, L.; Havers, F.P.; Taylor, C.A.; Stokley, S.; Talbot, H.K.; Schechter, R.; et al. Use of COVID-19 Vaccines for Persons Aged ≥6 Months: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2024–2025. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2024, 73, 819–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemaitelly, H.; Ayoub, H.H.; Coyle, P.; Tang, P.; Hasan, M.R.; Yassine, H.M.; Al Thani, A.A.; Al-Kanaani, Z.; Al-Kuwari, E.; Jeremijenko, A.; et al. Evaluating the Cost-Effectiveness of COVID-19 mRNA Primary-Series Vaccination in Qatar: An Integrated Epidemiological and Economic Analysis. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0331654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosser, L.A.; Perroud, J.; Chung, G.S.; Gebremariam, A.; Janusz, C.B.; Mercon, K.; Rose, A.M.; Avanceña, A.L.V.; Kim DeLuca, E.; Hutton, D.W. The Cost-Effectiveness of Vaccination Against COVID-19 Illness During the Initial Year of Vaccination. Vaccine 2025, 48, 126725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoli, G.; Nurchis, M.C.; Calabrò, G.E.; Damiani, G. Incremental Net Benefit and Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratio of COVID-19 Vaccination Campaigns: Systematic Review of Cost-Effectiveness Evidence. Vaccines 2023, 11, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.S.; Postma, M.; Fisman, D.; Mould-Quevedo, J. Cost-Effectiveness Models Assessing COVID-19 Booster Vaccines Across Eight Countries: A Review of Methods and Data Inputs. Vaccine 2025, 51, 126879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neilan, A.M.; Losina, E.; Bangs, A.C.; Flanagan, C.; Panella, C.; Eskibozkurt, G.E.; Mohareb, A.; Hyle, E.P.; Scott, J.A.; Weinstein, M.C.; et al. Clinical Impact, Costs, and Cost-Effectiveness of Expanded Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Testing in Massachusetts. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, e2908–e2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmanzadeh, F.; Malekpour, N.; Faramarzi, A.; Yusefzadeh, H. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Diagnostic Strategies for COVID-19 in Iran. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maya, S.; McCorvie, R.; Jacobson, K.; Shete, P.B.; Bardach, N.; Kahn, J.G. COVID-19 Testing Strategies for K–12 Schools in California: A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atherly, A.J.; van den Broek-Altenburg, E.M. The Effect of Medical Innovation on the Cost-Effectiveness of COVID-19–Related Policies in the United States Using a SIR Model. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardavas, C.; Zisis, K.; Nikitara, K.; Lagou, I.; Marou, V.; Aslanoglou, K.; Athanasakis, K.; Phalkey, R.; Leonardi-Bee, J.; Fernandez, E.; et al. Cost of the COVID-19 Pandemic Versus the Cost-Effectiveness of Mitigation Strategies in EU/UK/OECD: A Systematic Review. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e077602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandmann, F.G.; Davies, N.G.; Vassall, A.; Edmunds, W.J.; Jit, M. The Potential Health and Economic Value of SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination Alongside Physical Distancing in the UK: A Transmission Model-Based Future Scenario Analysis and Economic Evaluation. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 962–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.E.; Choi, H.; Choi, Y.; Lee, C.H. The Economic Impact of COVID-19 Interventions: A Mathematical Modeling Approach. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 993745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartsch, S.M.; Weatherwax, C.; Martinez, M.F.; Chin, K.L.; Wasserman, M.R.; Singh, R.D.; Heneghan, J.L.; Gussin, G.M.; Scannell, S.A.; White, C.; et al. Cost-Effectiveness of Severe Acute Respiratory Coronavirus Virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Testing and Isolation Strategies in Nursing Homes. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2024, 45, 754–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juneau, C.E.; Pueyo, T.; Bell, M.; Gee, G.; Collazzo, P.; Potvin, L. Lessons from Past Pandemics: A Systematic Review of Evidence-Based, Cost-Effective Interventions to Suppress COVID-19. Syst. Rev. 2022, 11, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbold, S.C.; Ashworth, M.; Finnoff, D.; Shogren, J.F.; Thunström, L. Physical Distancing Versus Testing with Self-Isolation for Controlling an Emerging Epidemic. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vardavas, C.; Nikitara, K.; Zisis, K.; Athanasakis, K.; Phalkey, R.; Leonardi-Bee, J.; Johnson, H.; Tsolova, S.; Ciotti, M.; Suk, J.E. Cost-Effectiveness of Emergency Preparedness Measures in Response to Infectious Respiratory Disease Outbreaks: A Systematic Review and Econometric Analysis. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e045113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, K.L.; Miller, G.F.; Coronado, F.; Meltzer, M.I. Estimated Resource Costs for Implementation of CDC’s Recommended COVID-19 Mitigation Strategies in Pre-Kindergarten Through Grade 12 Public Schools—United States, 2020–21 School Year. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 1917–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandjour, A. Health-Economic Evaluation of the Outpatient, Inpatient, and Public Health Sector in Germany: Insights from the First Three COVID-19 Waves. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0314164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratil, J.M.; Biallas, R.L.; Burns, J.; Arnold, L.; Geffert, K.; Kunzler, A.M.; Monsef, I.; Stadelmaier, J.; Wabnitz, K.; Litwin, T.; et al. Non-Pharmacological Measures Implemented in the Setting of Long-Term Care Facilities to Prevent SARS-CoV-2 Infections and Their Consequences: A Rapid Review. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 9, CD015085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, N.; Griffin, D.O.; Jarvis, M.S.; Cohen, K. Comparative Effectiveness of the SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines During Delta Dominance. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naranbhai, V.; Garcia-Beltran, W.F.; Chang, C.C.; Berrios Mairena, C.; Thierauf, J.C.; Kirkpatrick, G.; Onozato, M.L.; Cheng, J.; St Denis, K.J.; Lam, E.C.; et al. Comparative Immunogenicity and Effectiveness of mRNA-1273, BNT162b2, and Ad26.COV2.S COVID-19 Vaccines. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 225, 1141–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korang, S.K.; von Rohden, E.; Veroniki, A.A.; Ong, G.; Ngalamika, O.; Siddiqui, F.; Juul, S.; Nielsen, E.E.; Feinberg, J.B.; Petersen, J.J.; et al. Vaccines to Prevent COVID-19: A Living Systematic Review with Trial Sequential Analysis and Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0260733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graña, C.; Ghosn, L.; Evrenoglou, T.; Jarde, A.; Minozzi, S.; Bergman, H.; Buckley, B.S.; Probyn, K.; Villanueva, G.; Henschke, N.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of COVID-19 Vaccines. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 12, CD015477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotshild, V.; Hirsh-Raccah, B.; Miskin, I.; Muszkat, M.; Matok, I. Comparing the Clinical Efficacy of COVID-19 Vaccines: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosser, L.A.; Wallace, M.; Rose, A.M.; Mercon, K.; Janusz, C.B.; Gebremariam, A.; Hutton, D.W.; Leidner, A.J.; Zhou, F.; Ortega-Sanchez, I.R.; et al. Cost-Effectiveness of 2023–2024 COVID-19 Vaccination in U.S. Adults. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e2523688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiolet, T.; Kherabi, Y.; MacDonald, C.J.; Ghosn, J.; Peiffer-Smadja, N. Comparing COVID-19 Vaccines for Their Characteristics, Efficacy and Effectiveness Against SARS-CoV-2 and Variants of Concern: A Narrative Review. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2022, 28, 202–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, W.; Huang, F.; Zhang, K. Effectiveness of mRNA and Viral-Vector Vaccines in Epidemic Period Led by Different SARS-CoV-2 Variants: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e28623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, R.N.; Simmons, A.E.; Li, M.W.Z.; Gebretekle, G.B.; Xi, M.; Salvadori, M.I.; Warshawsky, B.; Wong, E.; Ximenes, R.; Andrew, M.K.; et al. Cost-Utility Analysis of COVID-19 Vaccination Strategies for Endemic SARS-CoV-2. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e2515534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Gonsalves, G.S.; Tan, S.T.; Kelly, J.D.; Rutherford, G.W.; Wachter, R.M.; Schechter, R.; Paltiel, A.D.; Lo, N.C. Comparing Frequency of Booster Vaccination to Prevent Severe COVID-19 by Risk Group in the United States. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, A.B.; Wu, S.L.; Toor, J.; Olivera Mesa, D.; Doohan, P.; Watson, O.J.; Winskill, P.; Charles, G.; Barnsley, G.; Riley, E.M.; et al. Long-Term Vaccination Strategies to Mitigate the Impact of SARS-CoV-2 Transmission: A Modelling Study. PLoS Med. 2023, 20, e1004195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, K.; Rhoads, J.P.; Surie, D.; Gaglani, M.; Ginde, A.A.; McNeal, T.; Talbot, H.K.; Casey, J.D.; Zepeski, A.; Shapiro, N.I.; et al. Vaccine Effectiveness of Primary Series and Booster Doses Against COVID-19–Associated Hospital Admissions in the United States: Living Test-Negative Design Study. BMJ 2022, 379, e072065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matrajt, L.; Leung, T. Evaluating the Effectiveness of Social Distancing Interventions to Delay or Flatten the Epidemic Curve of Coronavirus Disease. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 1740–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, N.; Sharp, S.J.; Chowell, G.; Shabnam, S.; Kawachi, I.; Lacey, B.; Massaro, J.M.; D’Agostino, R.B., Sr.; White, M. Physical Distancing Interventions and Incidence of Coronavirus Disease 2019: Natural Experiment in 149 Countries. BMJ 2020, 370, m2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huberts, N.F.D.; Thijssen, J.J.J. Optimal Timing of Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions During an Epidemic. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 305, 1366–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilinski, A.; Ciaranello, A.; Fitzpatrick, M.C.; Giardina, J.; Shah, M.; Salomon, J.A.; Kendall, E.A. Estimated Transmission Outcomes and Costs of SARS-CoV-2 Diagnostic Testing, Screening, and Surveillance Strategies Among a Simulated Population of Primary School Students. JAMA Pediatr. 2022, 176, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chevalier, J.M.; Han, A.X.; Hansen, M.A.; Klock, E.; Pandithakoralage, H.; Ockhuisen, T.; Girdwood, S.J.; Lekodeba, N.A.; de Nooy, A.; Khan, S.; et al. Impact and Cost-Effectiveness of SARS-CoV-2 Self-Testing Strategies in Schools: A Multicountry Modelling Analysis. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e078674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragonnet, R.; Hughes, A.E.; Shipman, D.S.; Meehan, M.T.; Henderson, A.S.; Briffoteaux, G.; Melab, N.; Tuyttens, D.; McBryde, E.S.; Trauer, J.M. Estimating the Impact of School Closures on the COVID-19 Dynamics in 74 Countries: A Modelling Analysis. PLoS Med. 2025, 22, e1004512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littlecott, H.; Krishnaratne, S.; Burns, J.; Rehfuess, E.; Sell, K.; Klinger, C.; Strahwald, B.; Movsisyan, A.; Metzendorf, M.I.; Schoenweger, P.; et al. Measures Implemented in the School Setting to Contain the COVID-19 Pandemic. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2024, 5, CD015029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See, I.; Paul, P.; Slayton, R.B.; Steele, M.K.; Stuckey, M.J.; Duca, L.; Srinivasan, A.; Stone, N.; Jernigan, J.A.; Reddy, S.C. Modeling Effectiveness of Testing Strategies to Prevent Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Nursing Homes—United States, 2020. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, e792–e798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarry, B.E.; Gandhi, A.D.; Barnett, M.L. COVID-19 Surveillance Testing and Resident Outcomes in Nursing Homes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yu, Y.; Petrovic, M.; Pei, X.; Tian, Q.B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.H. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Corresponding Control Measures on Long-Term Care Facilities: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Age Ageing 2023, 52, afac308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leidner, A.J.; Murthy, N.; Chesson, H.W.; Biggerstaff, M.; Stoecker, C.; Harris, A.M.; Acosta, A.; Dooling, K.; Bridges, C.B. Cost-Effectiveness of Adult Vaccinations: A Systematic Review. Vaccine 2019, 37, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klimek, P. Cost Effectiveness of Vaccinations: On the Complexity of Health Economic Analyses of Influenza, SARS-CoV-2 and RSV Vaccination. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforsch. Gesundheitsschutz 2025, 68, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim DeLuca, E.; Gebremariam, A.; Rose, A.; Biggerstaff, M.; Meltzer, M.I.; Prosser, L.A. Cost-Effectiveness of Routine Annual Influenza Vaccination by Age and Risk Status. Vaccine 2023, 41, 4239–4248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, M.; Stoecker, C.; Leidner, A.J.; Cho, B.H.; Pilishvili, T.; Kobayashi, M. Cost-Effectiveness of 15-Valent or 20-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine for U.S. Adults Aged 65 Years and Older and Adults 19 Years and Older with Underlying Conditions. Vaccine 2025, 44, 126567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K.J.; Brown, H.S.; Patel, U.; Tucker, D.; Becker, K. Cost-Effectiveness of a Comprehensive Immunization Program Serving High-Risk, Uninsured Adults. Prev. Med. 2020, 130, 105860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vadlamudi, N.K.; Lin, C.J.; Wateska, A.R.; Zimmerman, R.K.; Smith, K.J. A Budget Impact Analysis of 15- or 20-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine Use in All U.S. Adults Aged 50–64 Years Compared to Those with High-Risk Conditions from a U.S. Payer Perspective. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pampati, S.; Rasberry, C.N.; Timpe, Z.; McConnell, L.; Moore, S.; Spencer, P.; Lee, S.; Murray, C.C.; Adkins, S.H.; Conklin, S.; et al. Disparities in Implementing COVID-19 Prevention Strategies in Public Schools, United States, 2021–22 School Year. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2023, 29, 937–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, M.; Bahrami, M.; Menendez, M.; Balsa-Barreiro, J. Social Behavior and COVID-19: Analysis of the Social Factors Behind Compliance with Interventions Across the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.R.; Cyr, D.D.; Wruck, L.; Stefano, T.A.; Mehri, N.; Bursac, Z.; Munoz, R.; Baum, M.K.; Fluney, E.; Bhoite, P.; et al. COVID-19 Prevention Is Shaped by Polysocial Risk: A Cross-Sectional Study of Vaccination and Testing Disparities in Underserved Populations. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0328779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerstein, S.; Romeo-Aznar, V.; Dekel, M.; Miron, O.; Davidovitch, N.; Puzis, R.; Pilosof, S. The Interplay Between Vaccination and Social Distancing Strategies Affects COVID-19 Population-Level Outcomes. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2021, 17, e1009319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colosi, E.; Bassignana, G.; Contreras, D.A.; Poirier, C.; Boëlle, P.Y.; Cauchemez, S.; Yazdanpanah, Y.; Lina, B.; Fontanet, A.; Barrat, A.; et al. Screening and Vaccination Against COVID-19 to Minimise School Closure: A Modelling Study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 977–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilches, T.N.; Nourbakhsh, S.; Zhang, K.; Juden-Kelly, L.; Cipriano, L.E.; Langley, J.M.; Sah, P.; Galvani, A.P.; Moghadas, S.M. Multifaceted Strategies for the Control of COVID-19 Outbreaks in Long-Term Care Facilities in Ontario, Canada. Prev. Med. 2021, 148, 106564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, W.; Shim, E. Optimal Strategies for Social Distancing and Testing to Control COVID-19. J. Theor. Biol. 2021, 512, 110568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howerton, E.; Ferrari, M.J.; Bjørnstad, O.N.; Bogich, T.L.; Borchering, R.K.; Jewell, C.P.; Nichols, J.D.; Probert, W.J.M.; Runge, M.C.; Tildesley, M.J.; et al. Synergistic Interventions to Control COVID-19: Mass Testing and Isolation Mitigates Reliance on Distancing. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2021, 17, e1009518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, G.D.; Neumann, P.J.; Basu, A.; Brock, D.W.; Feeny, D.; Krahn, M.; Kuntz, K.M.; Meltzer, D.O.; Owens, D.K.; Prosser, L.A.; et al. Recommendations for Conduct, Methodological Practices, and Reporting of Cost-Effectiveness Analyses: Second Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. JAMA 2016, 316, 1093–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, M.C.; Neumann, P.J.; Ma, S.; Kim, D.D.; Cohen, J.T.; Nyaku, M.; Roberts, C.; Sinha, A.; Ollendorf, D.A. Frequency and Impact of the Inclusion of Broader Measures of Value in Economic Evaluations of Vaccines. Vaccine 2021, 39, 6727–6734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patikorn, C.; Cho, J.Y.; Lambach, P.; Hutubessy, R.; Chaiyakunapruk, N. Equity-Informative Economic Evaluations of Vaccines: A Systematic Literature Review. Vaccines 2023, 11, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, S.Y.; Foo, C.; Verma, M.; Hanvoravongchai, P.; Cheh, P.L.J.; Pholpark, A.; Marthias, T.; Hafidz, F.; Prawidya Putri, L.; Mahendradhata, Y.; et al. Mitigating the Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Vulnerable Populations: Lessons for Improving Health and Social Equity. Soc. Sci. Med. 2023, 328, 116007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco-Cazeaux, I.; Ferté, T.; Bruzek, C.; Gaudart, M.; Ngabdo, K.; Wittwer, J.; Francis-Oliviero, F. Targeting Health Equity Through Complex Health Interventions: Which Evaluation Methods and Designs Are Used? A Scoping Review. Public Health 2025, 249, 105962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, T.; Mujica-Mota, R.E.; Spencer, A.E.; Medina-Lara, A. Incorporating Equity Concerns in Cost-Effectiveness Analyses: A Systematic Literature Review. Pharmacoeconomics 2022, 40, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steijger, D.; Chatterjee, C.; Groot, W.; Pavlova, M. Challenges and Limitations in Distributional Cost-Effectiveness Analysis: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meunier, A.; Longworth, L.; Kowal, S.; Ramagopalan, S.; Love-Koh, J.; Griffin, S. Distributional Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Health Technologies: Data Requirements and Challenges. Value Health 2023, 26, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Domain (Assessed Criterion) | Typical Shortcoming Observed | n (%) of 74 Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Study perspective | Perspective not explicitly stated or inconsistent with stated objectives | 18 (24.3%) |

| Time horizon & discounting | Short horizons (<1 year) without justification; discount rates omitted | 22 (29.7%) |

| Model structure & transparency | Incomplete reporting of model assumptions or validation | 28 (37.8%) |

| Cost data sources | Use of aggregated or non-country-specific unit costs | 31 (41.9%) |

| Outcome measurement | Utilities derived from secondary sources without sensitivity testing | 26 (35.1%) |

| Uncertainty analysis | Absence of probabilistic sensitivity analysis | 33 (44.6%) |

| Equity or distributional analysis | No stratified or equity-adjusted analyses | 58 (78.4%) |

| CHEERS 2022 compliance | Partial adherence (<70% of items reported) | 46 (62.2%) |

| Characteristic Categories/Definitions | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Study design | |

| Modelling analyses (decision-analytic, compartmental, microsimulation) | 68 (91.9%) |

| Trial-based economic evaluations | 6 (8.1%) |

| Geographical setting | |

| USA/Canada | 46 (62.2%) |

| EU/UK | 21 (28.4%) |

| Other high-income countries | 5 (6.8%) |

| Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) | 2 (2.7%) |

| Intervention types | |

| Vaccination interventions | 41 (55.4%) |

| Testing and screening strategies | 26 (35.1%) |

| Non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) | 21 (28.4%) |

| Combined/multicomponent strategies | 32 (43.2%) |

| Economic perspective | |

| Healthcare payer/provider | 34 (45.9%) |

| Societal | 29 (39.2%) |

| Not reported | 11 (14.9%) |

| Outcome measures | |

| ICER per QALY gained | 50 (67.6%) |

| Net monetary benefit (NMB) | 16 (21.6%) |

| Cases/hospitalizations/deaths averted | 24 (32.4%) |

| Utility or life-years gained without ICER reporting | 8 (10.8%) |

| Equity considerations | |

| Subgroup/stratified analyses | 12 (16.2%) |

| Use of DCEA/ECEA frameworks | 4 (5.4%) |

| Inclusion of long-term societal outcomes | |

| “Long COVID,” productivity losses, mental health, educational disruption | 9 (12.2%) |

| Reporting quality | |

| Explicit alignment with CHEERS 2022 checklist | 28 (37.8%) |

| Vaccine Type | Healthcare Setting | Cost-Effectiveness (ICER/QALY, Cost-Saving, NNV) | Effectiveness (VE, Hospitalization/ Death Reduction) | Key Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA (BNT162b2, mRNA-1273) | Hospitals | ICER as low as $23,308/QALY in ≥65 years; NNV for hospitalization: 3130 (mRNA-1273), 15,472 (BNT162b2); cost-saving in high-risk | VE > 90% for symptomatic infection; highest reduction in hospitalization and death | Highest cost-effectiveness and VE, especially in older adults and high-risk; mRNA-1273 slightly superior to BNT162b2; cost-saving in some analyses | [16,17,35,36,37,38,39,40,41] |

| mRNA (BNT162b2, mRNA-1273) | Long-Term Care Facilities | ICER most favorable in ≥65 years and high-risk; cost-saving in targeted strategies | VE > 90% for severe disease; strong reduction in hospitalization/death | Targeted vaccination in vulnerable populations most cost-effective; mRNA vaccines preferred | [16,37,38,40,41] |

| mRNA (BNT162b2, mRNA-1273) | Schools | ICER > $200,000/QALY in children/adolescents; less favorable, highly sensitive to assumptions | VE high for infection, but lower for severe outcomes in youth | Effective, but cost-effectiveness less robust due to low risk of severe disease; benefit greatest in high-risk students | [16,38,40,41] |

| Viral Vector (Ad26.COV2.S, ChAdOx1) | Hospitals | ICER higher than mRNA; NNV for hospitalization: 26, CE.COV2.S; less cost-effective overall | VE 67–70% for symptomatic infection; strong reduction in mortality | Lower VE and cost-effectiveness than mRNA; may be more cost-effective for mortality reduction in select high-risk | [17,35,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59] |

| Viral Vector (Ad26.COV2.S, ChAdOx1) | Long-Term Care Facilities | ICER higher than mRNA; cost-effectiveness varies by variant and risk | VE 67–70% for severe disease; mortality reduction | Less cost-effective than mRNA; may be considered in resource-limited settings or for mortality reduction | [17,37,38,41,42] |

| Viral Vector (Ad26.COV2.S, ChAdOx1) | Schools | ICER not well-defined; cost-effectiveness less favorable due to low severe disease risk | VE moderate for infection; low for severe outcomes in youth | Effective, but less cost-effective than mRNA; limited data for direct comparison in schools | [17,38,41,42] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Raycheva, R.; Kostadinov, K.; Rangelova, V.; Kevorkyan, A. Economic Analyses of COVID-19 Interventions: A Narrative Review of Global Evidence. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3249. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243249

Raycheva R, Kostadinov K, Rangelova V, Kevorkyan A. Economic Analyses of COVID-19 Interventions: A Narrative Review of Global Evidence. Healthcare. 2025; 13(24):3249. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243249

Chicago/Turabian StyleRaycheva, Ralitsa, Kostadin Kostadinov, Vanya Rangelova, and Ani Kevorkyan. 2025. "Economic Analyses of COVID-19 Interventions: A Narrative Review of Global Evidence" Healthcare 13, no. 24: 3249. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243249

APA StyleRaycheva, R., Kostadinov, K., Rangelova, V., & Kevorkyan, A. (2025). Economic Analyses of COVID-19 Interventions: A Narrative Review of Global Evidence. Healthcare, 13(24), 3249. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243249