What Are the Determinants of the Sex/Gender Difference in Duration of Work Absence for Musculoskeletal Disorders? A Mixed-Studies Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Methodologic Quality Appraisal of Selected Individual Studies

2.4. Data Extraction and Analysis

2.5. Synthesis of Quantitative Studies

2.6. Synthesis of Qualitative Studies

2.7. Mixed Synthesis

3. Results

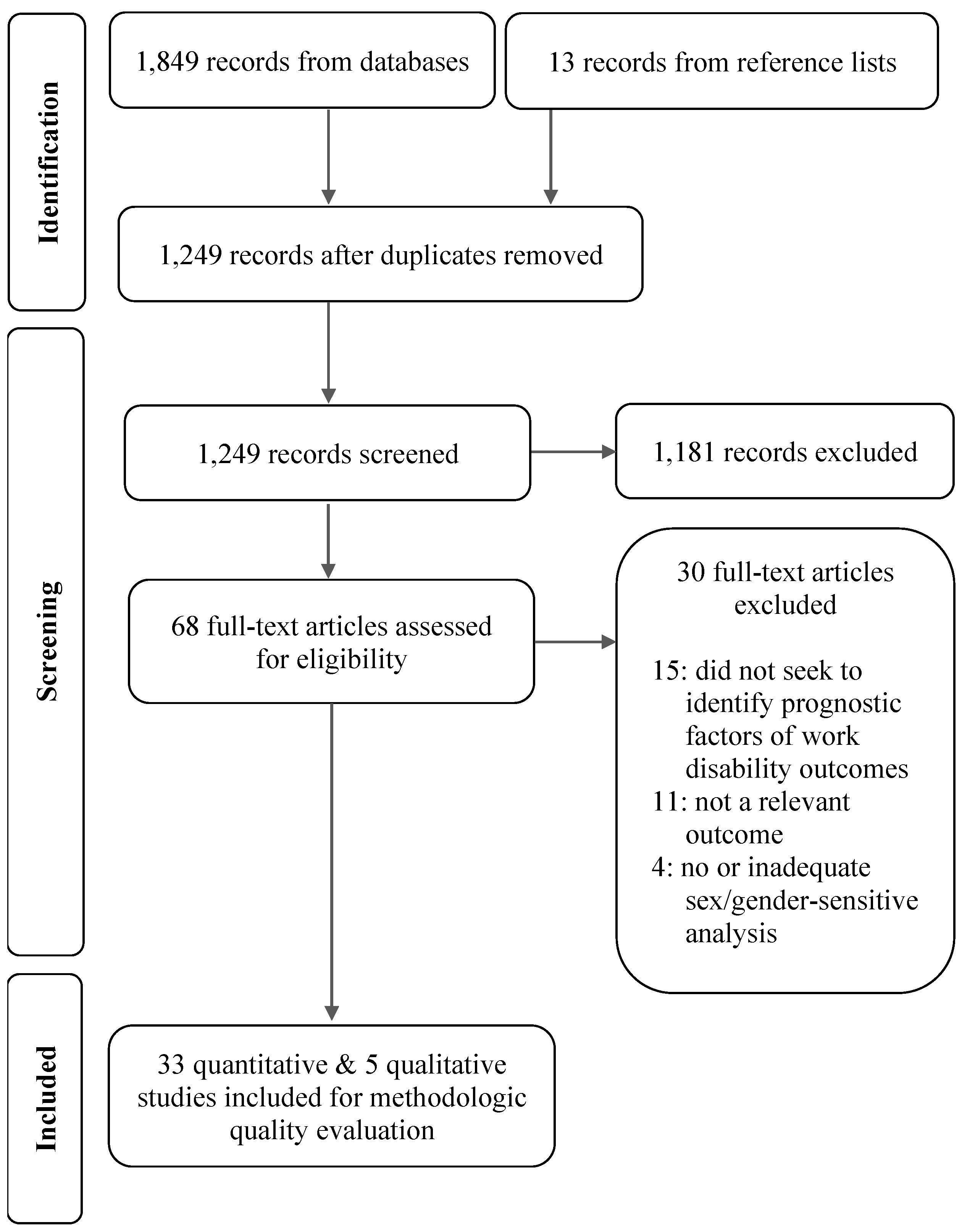

3.1. Results of Bibliographic Search

3.2. Results of Methodologic Quality Appraisal

3.3. Findings from the Quantitative Literature

3.3.1. MSD Disability Outcomes Examined

3.3.2. Sex/Gender Differences in Burden of MSD Work Disability

3.3.3. Studies Addressing the MSD Disability Sex/Gender Gap Directly

3.3.4. Quality of the Evidence for Explanatory Factors of Increased Duration of MSD Work Absence

3.3.5. Quality of the Evidence for Explanatory Factors of the Incidence or Number of Episodes of Prolonged MSD Work Absence

3.3.6. Quality of the Evidence for Explanatory Factors of Failure to RTW

3.3.7. Quality of the Evidence for Explanatory Factors of Receiving an MSD Disability Pension

3.4. Findings from the Qualitative Literature

3.4.1. Work Role and Identity

3.4.2. Domestic Responsibilities

3.4.3. Social Support

3.4.4. Working Conditions

3.4.5. Transportation to Work

3.4.6. Gender-Biased Attitudes and Behaviors of Gatekeepers

3.4.7. Gender Differences in Injured Workers’ Expectations, Attitudes or Beliefs

3.4.8. Line of Argument: Synthesis of Second-Order Concepts

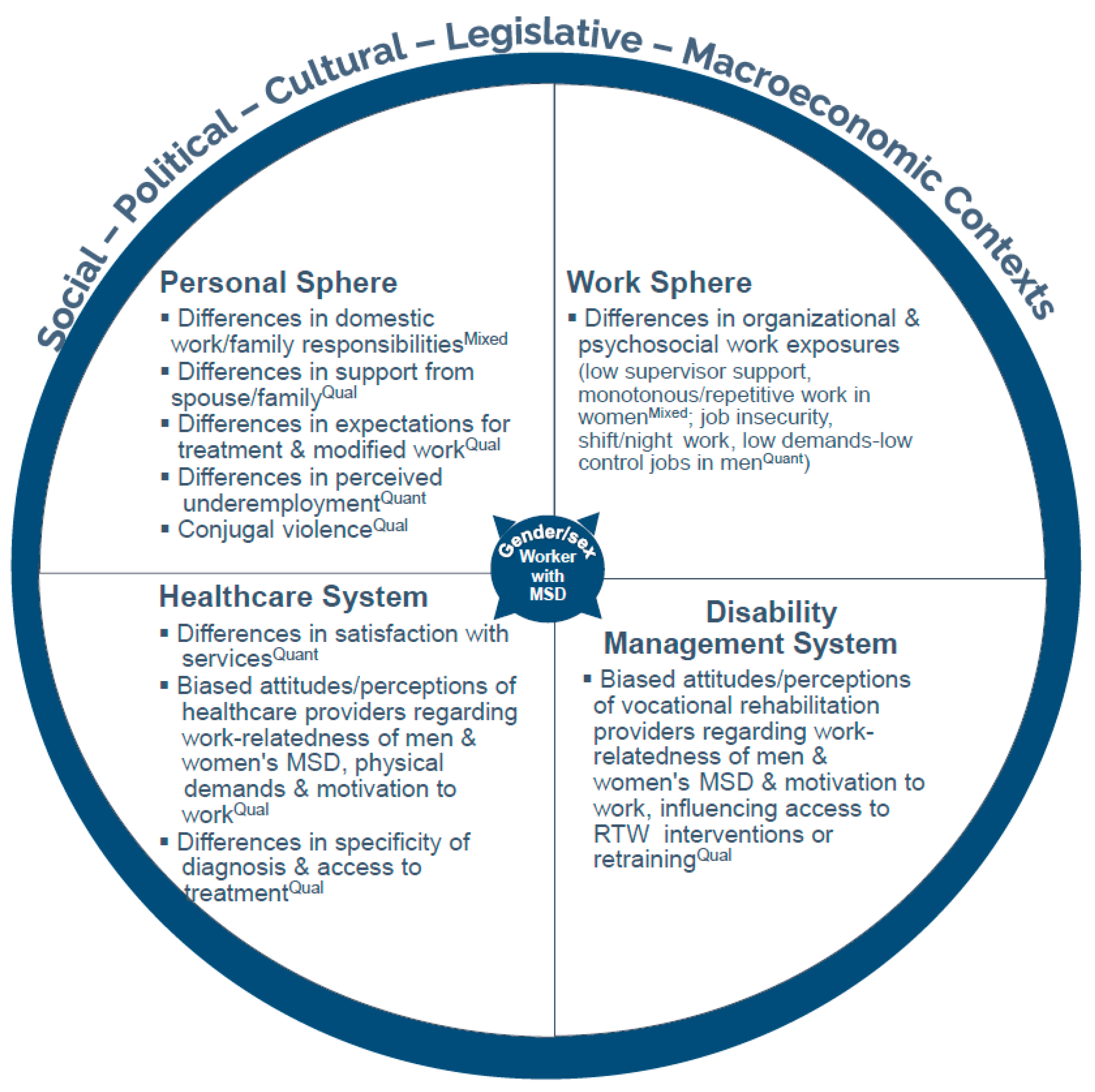

3.5. Mixed Synthesis Results

3.5.1. Hypothesized Determinants in the Personal Sphere

3.5.2. Hypothesized Determinants in the Work Sphere

3.5.3. Hypothesized Determinants in the Healthcare and Disability Management System Spheres

4. Discussion

4.1. Highlights of Main Findings

4.2. Comparison to Other Studies

4.3. Implications of Findings

- In many countries it is primary care professionals and medical specialists in the community who are the first to evaluate and treat workers in their practices, and they need to be trained to better diagnose and treat WMSDs.

- In relation to employers and relevant occupational health, workers’ compensation and rehabilitation organizations and authorities need to work with healthcare professionals to develop effective communication strategies between healthcare providers and workplaces regarding modified work options that reduce exposure to workplace factors that contribute to duration of work disability.

- Those in the workplace, including employers, supervisors, other managers and worker representatives responsible for health and safety and for the RTW of injured workers, and the occupational health personnel providing services within the workplace, should be trained to recognize MSD risk factors that may be specific to men or women, as well as differences between men and women in factors that influence rehabilitation and RTW, and to develop sex- and gender-sensitive approaches to MSD prevention and rehabilitation in collaboration with all relevant stakeholders.

- Similarly, those working in clinical and vocational rehabilitation settings and in workers’ compensation or other work insurance agencies or social welfare pension programs should be trained to recognize potential differences between men and women in terms of MSD risk factors or factors that influence rehabilitation and RTW following an MSD.For all these stakeholders, this training could include how to recognize the health risks associated with the work demands experienced by women, including the effects of highly repetitive work with less obvious physical exertion, and the effects of cognitive and emotional demands, especially in service industries where work involves interactions with patients, clients, students and others, such as healthcare and education, for example [105]. This training could also draw attention to the importance of promoting work–life balance necessary for rest and recovery from injury through workplace practices and policies, and the importance of offering more accommodation and greater flexibility with respect to vocational rehabilitation choices for women with MSDs, as well as men.

- Inequities in the division of domestic work highlighted in this review suggest that healthcare providers and vocational rehabilitation professionals should be attentive to the need to provide support for women with respect to these issues and ensure that they receive resources to address and reduce their domestic burdens to promote recovery and RTW.

4.4. Strengths and Limitations of the Review

4.5. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Association of Workers’ Compensation Boards of Canada. Annual Key Statistical Measures Standard Report. 2012. Available online: https://awcbc.org/data-and-statistics/key-statistical-measures/detailed-key-statistical-measures-report (accessed on 22 June 2015).

- Baldwin, M.L. Reducing the Costs of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders: Targeting Strategies to Chronic Disability Cases. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2004, 14, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagenais, S.; Caro, J.; Haldeman, S. A Systematic Review of Low Back Pain Cost of Illness Studies in the United States and Internationally. Spine J. 2008, 8, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.L.; de Luca, K.; Haile, L.M.; Steinmetz, J.D.; Culbreth, G.T.; Cross, M.; Kopec, J.A.; Ferreira, P.H.; Blyth, F.M.; Buchbinder, R.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Low Back Pain, 1990–2020, Its Attributable Risk Factors, and Projections to 2050: A Systematic Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023, 5, e316–e329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Research Council; Institute of Medicine. Musculoskeletal Disorders and the Workplace: Low Back and Upper Extremities; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001.

- Chénard, C.; Mantha-Bélisle, M.-M.; Vézina, M. Risques Psychosociaux du Travail: Des Risques à la Santé Mesurables et Modifiables. 2022. Available online: https://www.inspq.qc.ca/sites/default/files/publications/2894-risques-psychosociaux-travail-risques-sante-mesurables.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Roquelaure, Y. Musculoskeletal Disorders and Psychosocial Factors at Work; ETUI Aisbl: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stock, S.; Botan, S.; Lazreg, F.; Vézina, N.; Imbeau, D.; Gilbert, L.; Poirier-Lavallée, M.; Vézina-Nadon, L.; Selmi, S.; Cardinal, N.; et al. Contraintes de Travail Associées Aux Troubles Musculo-Squelettiques–Guide D’Utilisation Pour Une Évaluation Rapide; Institut National de santé Publique du Québec: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2021.

- Bongers, P.M.; Ijmker, S.; van den Heuvel, S.; Blatter, B.M. Epidemiology of Work Related Neck and Upper Limb Problems: Psychosocial and Personal Risk Factors (Part I) and Effective Interventions from a Bio Behavioural Perspective (Part II). J. Occup. Rehabil. 2006, 16, 272–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, B.R.; Vieira, E.R. Risk Factors for Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders: A Systematic Review of Recent Longitudinal Studies. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2010, 53, 285–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauke, A.; Flintrop, J.; Brun, E.; Rugulies, R. The Impact of Work-Related Psychosocial Stressors on the Onset of Musculoskeletal Disorders in Specific Body Regions: A Review and Meta-Analysis of 54 Longitudinal Studies. Work Stress 2011, 25, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, J.; Ochsmann, E.; Kraus, T.; Lang, J.W.B. Psychosocial Work Stressors as Antecedents of Musculoskeletal Problems: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Stability-Adjusted Longitudinal Studies. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 1163–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macfarlane, G.J.; Pallewatte, N.; Paudyal, P.; Blyth, F.M.; Coggon, D.; Crombez, G.; Linton, S.; Leino-Arjas, P.; Silman, A.J.; Smeets, R.J.; et al. Evaluation of Work-Related Psychosocial Factors and Regional Musculoskeletal Pain: Results from a EULAR Task Force. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2009, 68, 885–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedhammer, I.; Bertrais, S.; Witt, K. Psychosocial Work Exposures and Health Outcomes: A Meta-Review of 72 Literature Reviews with Meta-Analysis. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2021, 47, 489–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K.; Gouin, J.-P.; Hantsoo, L. Close Relationships, Inflammation, and Health. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2010, 35, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.D.; Sauter, S.L. (Eds.) Beyond Biomechanics: Psychosocial Aspects of Musculoskeletal Disorders in Office Work; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Finestone, H.M.; Alfeeli, A.; Fisher, W.A. Stress-Induced Physiologic Changes as a Basis for the Biopsychosocial Model of Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain: A New Theory? Clin. J. Pain 2008, 24, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexanderson, K.A.E.; Borg, K.E.; Hensing, G.K.E. Sickness Absence with Low-Back, Shoulder, or Neck Diagnoses: An 11-Year Follow-up Regarding Gender Differences in Sickness Absence and Disability Pension. Work 2005, 25, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leijon, M.; Hensing, G.; Alexanderson, K. Sickness Absence Due to Musculoskeletal Diagnoses: Association with Occupational Gender Segregation. Scand. J. Public Health 2004, 32, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koehoorn, M.; Fan, J.; McLeod, C. Gender, Sex & Differences in Disability Duration for Work-Related Injury and Illness (Presentation). 2012. Available online: https://pwhr.sites.olt.ubc.ca/files/2012/06/Gender-presentation-CARWH-2012.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Stock, S.; Funes, A.; Delisle, A.; St-Vincent, M.; Turcot, A.; Messing, K. Troubles musculo-squelettiques [Chapter 9: Musculoskeletal disorders]. In Enquête Québécoise sur des Conditions de Travail, D’emploi, de Santé et de Sécurité du Travail (EQCOTESST) [Quebec Survey on Working and Employment Conditions and Occupational Health and Safety]; Vézina, M., Cloutier, E., Stock, S., Lippel, K., Fortin, E., Delisle, A., St-Vincent, M., Funes, A., Duguay, P., Vézina, S., et al., Eds.; R-691; Institut de Recherche Robert-Sauvé en Santé et Sécurité du Travail, Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec, Institut de la Statistique du Québec: Québec, QC, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Stock, S.; Nicolakakis, N. Gender Differences in the Duration of Work Absence for Non-Traumatic Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders (Presentation). In Proceedings of the Workers’ Compensation Research Group Meeting, Liberty Mutual Research Institute for Safety, Hopkinton, MA, USA, 3–4 March 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nastasia, I.; Coutu, M.-F.; Cibotaru, A. Prévention de L’Incapacité Prolongée chez les Travailleurs Indemnisés pour Troubles Musculo-Squelettiques: Une Revue Systématique de la Littérature. Mise à Jour 2008–2013 [Prevention of Prolonged Disability in Workers Compensated for Musculoskeletal Disorders: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Updated 2008–2013]; R-841; Institut de Recherche Robert-Sauvé en Santé et en Sécurité du Travail: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2014; p. 77.

- Lippel, K. Preserving Workers’ Dignity in Workers’ Compensation Systems: An International Perspective. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2012, 55, 519–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenstra, I.; Irvin, E.; Heymans, M.; Mahood, Q.; Hogg-Johnson, S. Systematic Review of Prognostic Factors for Workers’ Time Away from Work Due to Acute Low-Back Pain: An Update of a Systematic Review. Final Report to Workers’ Compensation Board of Manitoba; Institute for Work & Health: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, W.S.; van der Windt, D.A.; Main, C.J.; Loisel, P.; Linton, S.J.; “Decade of the Flags” Working Group. Early Patient Screening and Intervention to Address Individual-Level Occupational Factors (“Blue Flags”) in Back Disability. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2009, 19, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research. What Is Gender? What Is Sex? 2023. Available online: http://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/48642.html (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Clow, B.; Pederson, A.; Haworth-Brockman, M.; Bernier, J. Rising to the Challenge: Sex- and Gender-Based Analysis for Health Planning, Policy and Research in Canada; Atlantic Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health: Halifax, NS, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Milan, A.; Keown, L.-A.; Urquijo Covadonga, R. Women in Canada: A Gender-Based Statistical Report: Families, Living Arrangements and Unpaid Work; 89-503–X; Minister of Industry, Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2011.

- Minister of Industry. General Social Survey—2010 Overview of the Time Use of Canadians; 89-647–X; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2011.

- Krieger, N. Genders, Sexes, and Health: What Are the Connections—And Why Does It Matter? Int. J. Epidemiol. 2003, 32, 652–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messing, K. 2021. Chapter 5: Same, different or understudied? In Bent Out of Shape: Shame, Solidarity, and Women’s Bodies at Work; Between the Lines Books: Toronto, ON, Canada; 276p, ISBN 9781771135412.

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, J.A.; Côté, P.; Bombardier, C. Evaluation of the Quality of Prognosis Studies in Systematic Reviews. Ann. Intern. Med. 2006, 144, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayden, J.A.; van der Windt, D.A.; Cartwright, J.L.; Côté, P.; Bombardier, C. Assessing Bias in Studies of Prognostic Factors. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013, 158, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Methodology Checklist: Qualitative Studies. 2009. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg6/resources/the-guidelines-manual-appendices-bi-2549703709/chapter/appendix-h-methodology-checklist-qualitative-studies (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- MacDermid, J.C. Sex and Gender Methods Review Tool. 2017; Unpublished Work. [Google Scholar]

- Doull, M.; Runnels, V.; Tudiver, S.; Boscoe, M. Sex and Gender in Systematic Reviews: Planning Tool. 2011. Available online: https://methods.cochrane.org/equity/sites/methods.cochrane.org.equity/files/uploads/SRTool_PlanningVersionSHORTFINAL.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2016).

- Welch, V.; Puil, L.; Shea, B.; Runnels, V.; Doull, M.; Tudiver, S.; Boscoe, M.; For the Sex/Gender Methods Group. Addressing Sex/Gender in Systematic Reviews: Cochrane Musculoskeletal Group Briefing Note. 2014. Available online: https://methods.cochrane.org/equity/sites/methods.cochrane.org.equity/files/uploads/KTBriefingNote_MSKFINAL.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Boscoe, M.; Tudiver, S.; Doull, M.; Runnels, V.E. Sex and Gender in Systematic Reviews. In Rising to the Challenge: Sex- and Gender-Based Analysis for Health Planning, Policy and Research in Canada; Clow, B., Pederson, A., Haworth-Brockman, M., Bernier, J., Eds.; Atlantic Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health: Halifax, NS, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tudiver, S.; Boscoe, M.; Runnels, V.; Doull, M. Challenging “Dis-Ease”: Sex, Gender and Systematic Reviews in Health. In What a Difference Sex and Gender Make: A Gender, Sex and Health Research Casebook; Coen, S., Banister, E., Eds.; Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Institute of Gender & Health: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Messing, K.; Stock, S.R.; Tissot, F. Should Studies of Risk Factors for Musculoskeletal Disorders Be Stratified by Gender? Lessons from the 1998 Québec Health and Social Survey. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2009, 35, 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Kunz, R.; Brozek, J.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Rind, D.; Devereaux, P.J.; Montori, V.M.; Freyschuss, B.; Vist, G.; et al. GRADE Guidelines 6. Rating the Quality of Evidence—Imprecision. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 1283–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Kunz, R.; Woodcock, J.; Brozek, J.; Helfand, M.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Glasziou, P.; Jaeschke, R.; Akl, E.A.; et al. GRADE Guidelines: 7. Rating the Quality of Evidence—Inconsistency. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 1294–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Kunz, R.; Woodcock, J.; Brozek, J.; Helfand, M.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Jaeschke, R.; Vist, G.; et al. GRADE Guidelines: 8. Rating the Quality of Evidence—Indirectness. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 1303–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Montori, V.; Vist, G.; Kunz, R.; Brozek, J.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Djulbegovic, B.; Atkins, D.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; et al. GRADE Guidelines: 5. Rating the Quality of Evidence—Publication Bias. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 1277–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Sultan, S.; Glasziou, P.; Akl, E.A.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Atkins, D.; Kunz, R.; Brozek, J.; Montori, V.; et al. GRADE Guidelines: 9. Rating up the Quality of Evidence. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 1311–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Vist, G.; Kunz, R.; Brozek, J.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Montori, V.; Akl, E.A.; Djulbegovic, B.; Falck-Ytter, Y. GRADE Guidelines: 4. Rating the Quality of Evidence—Study Limitations (Risk of Bias). J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schünemann, H.; Brożek, J.; Guyatt, G.; Oxman, A. Handbook for Grading the Quality of Evidence and the Strength of Recommendations Using the GRADE Approach. 2013. Available online: https://gdt.gradepro.org/app/handbook/handbook.html (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Huguet, A.; Hayden, J.A.; Stinson, J.; McGrath, P.J.; Chambers, C.T.; Tougas, M.E.; Wozney, L. Judging the Quality of Evidence in Reviews of Prognostic Factor Research: Adapting the GRADE Framework. Syst. Rev. 2013, 2, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, J.A.; Côté, P.; Steenstra, I.A.; Bombardier, C. Identifying Phases of Investigation Helps Planning, Appraising, and Applying the Results of Explanatory Prognosis Studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 552–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noblit, G.W.; Hare, R.D. Meta-Ethnography: Synthesising Qualitative Studies; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Britten, N.; Campbell, R.; Pope, C.; Donovan, J.; Morgan, M.; Pill, R. Using Meta Ethnography to Synthesise Qualitative Research: A Worked Example. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2002, 7, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, R.; Pound, P.; Morgan, M.; Daker-White, G.; Britten, N.; Pill, R.; Yardley, L.; Pope, C.; Donovan, J. Evaluating Meta-Ethnography: Systematic Analysis and Synthesis of Qualitative Research. Health Technol. Assess. 2011, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacEachen, E.; Clarke, J.; Franche, R.-L.; Irvin, E.; Workplace-Based Return to Work Literature Review Group. Systematic Review of the Qualitative Literature on Return to Work after Injury. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2006, 32, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandelowski, M.; Voils, C.I.; Barroso, J. Defining and Designing Mixed Research Synthesis Studies. Res. Sch. 2006, 13, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski, M.; Voils, C.I.; Leeman, J.; Crandell, J.L. Mapping the Mixed Methods–Mixed Research Synthesis Terrain. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2012, 6, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Joanna Briggs Institute. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual: Methodology for JBI Mixed Methods Systematic Reviews—2014 Edition/Supplement. 2014. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Annette-Bourgault/post/Integrative_review_VS_systematic_review/attachment/6247240119eb97629d40581b/AS%3A1140087463124994%401648829441830/download/Joanna+Briggs+ReviewersManual_Mixed-Methods-Review-Methods-2014-ch1%281%29.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Pluye, P.; Hong, Q.N. Combining the Power of Stories and the Power of Numbers: Mixed Methods Research and Mixed Studies Reviews. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.M.; Koehoorn, M.; Bültmann, U.; McLeod, C.B. Impact of Anxiety and Depression Disorders on Sustained Return to Work after Work-Related Musculoskeletal Strain or Sprain: A Gender Stratified Cohort Study. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2021, 47, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, A.M.; Koehoorn, M.; Bültmann, U.; McLeod, C.B. Pre-Existing Anxiety and Depression Disorders and Return to Work after Musculoskeletal Strain or Sprain: A Phased-Based Approach. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2023, 33, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laaksonen, M.; Mastekaasa, A.; Martikainen, P.; Rahkonen, O.; Piha, K.; Lahelma, E. Gender Differences in Sickness Absence–the Contribution of Occupation and Workplace. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2010, 36, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pekkala, J.; Rahkonen, O.; Pietiläinen, O.; Lahelma, E.; Blomgren, J. Sickness Absence Due to Different Musculoskeletal Diagnoses by Occupational Class: A Register-Based Study among 1.2 Million Finnish Employees. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018, 75, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirén, M.; Viikari-Juntura, E.; Arokoski, J.; Solovieva, S. Work Participation and Working Life Expectancy after a Disabling Shoulder Lesion. Occup. Environ. Med. 2019, 76, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirén, M.; Viikari-Juntura, E.; Arokoski, J.; Solovieva, S. Physical and Psychosocial Work Exposures as Risk Factors for Disability Retirement Due to a Shoulder Lesion. Occup. Environ. Med. 2019, 76, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirén, M.; Viikari-Juntura, E.; Arokoski, J.; Solovieva, S. Occupational Differences in Disability Retirement Due to a Shoulder Lesion: Do Work-Related Factors Matter? Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2020, 93, 983–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionne, C.E.; Bourbonnais, R.; Frémont, P.; Rossignol, M.; Stock, S.R.; Nouwen, A.; Larocque, I.; Demers, E. Determinants of “Return to Work in Good Health” among Workers with Back Pain Who Consult in Primary Care Settings: A 2-Year Prospective Study. Eur. Spine J. 2007, 16, 641–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foss, L.; Gravseth, H.M.; Kristensen, P.; Claussen, B.; Mehlum, I.S.; Knardahl, S.; Skyberg, K. The Impact of Workplace Risk Factors on Long-Term Musculoskeletal Sickness Absence: A Registry-Based 5-Year Follow-up from the Oslo Health Study. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2011, 53, 1478–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjesdal, S.; Ringdal, P.R.; Haug, K.; Mæland, J.G. Predictors of Disability Pension in Long-Term Sickness Absence: Results from a Population-Based and Prospective Study in Norway 1994-1999. Eur. J. Public Health 2004, 14, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjesdal, S.; Bratberg, E.; Mæland, J.G. Gender Differences in Disability after Sickness Absence with Musculoskeletal Disorders: Five-Year Prospective Study of 37,942 Women and 26,307 Men. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2011, 12, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, K.B.; Holte, H.H.; Tambs, K.; Bjerkedal, T. Socioeconomic Factors and Disability Retirement from Back Pain: A 1983–1993 Population-Based Prospective Study in Norway. Spine 2000, 25, 2480–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagen, K.B.; Tambs, K.; Bjerkedal, T. What Mediates the Inverse Association between Education and Occupational Disability from Back Pain?—A Prospective Cohort Study from the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study in Norway. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 63, 1267–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kjellberg, K.; Lundin, A.; Falkstedt, D.; Allebeck, P.; Hemmingsson, T. Long-Term Physical Workload in Middle Age and Disability Pension in Men and Women: A Follow-up Study of Swedish Cohorts. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2016, 89, 1239–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, P.; Bjerkedal, T.; Irgens, L.M. Early Life Determinants of Musculoskeletal Sickness Absence in a Cohort of Norwegians Born in 1967–1976. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 64, 646–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lallukka, T.; Mauramo, E.; Lahelma, E.; Rahkonen, O. Economic Difficulties and Subsequent Disability Retirement. Scand. J. Public Health 2015, 43, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lederer, V.; Rivard, M.; Mechakra-Tahiri, S.D. Gender Differences in Personal and Work-Related Determinants of Return-to-Work Following Long-Term Disability: A 5-Year Cohort Study. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2012, 22, 522–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lederer, V.; Rivard, M. Compensation Benefits in a Population-Based Cohort of Men and Women on Long-Term Disability after Musculoskeletal Injuries: Costs, Course, Predictors. Occup. Environ. Med. 2014, 71, 772–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maas, E.T.; Koehoorn, M.; McLeod, C.B. Return-to-Work for Multiple Jobholders with a Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorder: A Population-Based, Matched Cohort in British Columbia. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäntyniemi, A.; Oksanen, T.; Salo, P.; Virtanen, M.; Sjösten, N.; Pentti, J.; Kivimäki, M.; Vahtera, J. Job Strain and the Risk of Disability Pension Due to Musculoskeletal Disorders, Depression or Coronary Heart Disease: A Prospective Cohort Study of 69 842 Employees. Occup. Environ. Med 2012, 69, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opsahl, J.; Eriksen, H.R.; Tveito, T.H. Do Expectancies of Return to Work and Job Satisfaction Predict Actual Return to Work in Workers with Long Lasting LBP? BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2016, 17, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salonen, L.; Blomgren, J.; Laaksonen, M. From Long-Term Sickness Absence to Disability Retirement: Diagnostic and Occupational Class Differences within the Working-Age Finnish Population. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.; Bielecky, A.; Ibrahim, S.; Mustard, C.; Saunders, R.; Beaton, D.; Koehoorn, M.; McLeod, C.; Scott-Marshall, H.; Hogg-Johnson, S. Impact of Pre-Existing Chronic Conditions on Age Differences in Sickness Absence after a Musculoskeletal Work Injury: A Path Analysis Approach. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2014, 40, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svärd, A.; Pipping, H.; Lahti, J.; Mänty, M.; Rahkonen, O.; Lahelma, E.; Lallukka, T. Joint Association of Overweight and Common Mental Disorders with Diagnosis-Specific Disability Retirement: A Follow-Up Study Among Female and Male Employees. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018, 60, 979–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svärd, A.; Lahti, J.; Mänty, M.; Roos, E.; Rahkonen, O.; Lahelma, E.; Lallukka, T. Weight Change among Normal Weight, Overweight and Obese Employees and Subsequent Diagnosis-Specific Sickness Absence: A Register-Linked Follow-up Study. Scand. J. Public Health 2020, 48, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahtera, J.; Laine, S.; Virtanen, M.; Oksanen, T.; Koskinen, A.; Pentti, J.; Kivimaki, M. Employee Control over Working Times and Risk of Cause-Specific Disability Pension: The Finnish Public Sector Study. Occup. Environ. Med. 2010, 67, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borg, K.; Hensing, G.; Alexanderson, K. Predictive Factors for Disability Pension—An 11-Year Follow up of Young Persons on Sick Leave Due to Neck, Shoulder, or Back Diagnoses. Scand. J. Public Health 2001, 29, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatchel, R.J.; Mayer, T.G.; Kidner, C.L.; McGeary, D.D. Are Gender, Marital Status or Parenthood Risk Factors for Outcome of Treatment for Chronic Disabling Spinal Disorders? J. Occup. Rehabil. 2005, 15, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gjesdal, S.; Holmaas, T.H.; Monstad, K.; Hetlevik, Ø. New Episodes of Musculoskeletal Conditions among Employed People in Norway, Sickness Certification and Return to Work: A Multiregister-Based Cohort Study from Primary Care. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e017543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holte, H.H.; Tambs, K.; Bjerkedal, T. Manual Work as Predictor for Disability Pensioning with Osteoarthritis among the Employed in Norway 1971–1990. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2000, 29, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, P.-O.; Mattsson, B.; Marklund, S.; Wimo, A. Health and Disability Pension—An Intersection of Disease, Psychosocial Stress and Gender. Long Term Follow up of Persons with Impairment of the Locomotor System. Work 2008, 31, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahelma, E.; Laaksonen, M.; Lallukka, T.; Martikainen, P.; Pietiläinen, O.; Saastamoinen, P.; Gould, R.; Rahkonen, O. Working Conditions as Risk Factors for Disability Retirement: A Longitudinal Register Linkage Study. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliv, S.; Gustafsson, E.; Baloch, A.N.; Hagberg, M.; Sandén, H. Important Work Demands for Reducing Sickness Absence among Workers with Neck or Upper Back Pain: A Prospective Cohort Study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2019, 20, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlgren, C.; Hammarström, A. Back to Work? Gendered Experiences of Rehabilitation. Scand. J. Public Health 2000, 28, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liedberg, G.M.; Henriksson, C.M. Factors of Importance for Work Disability in Women with Fibromyalgia: An Interview Study. Arthritis Rheum. 2002, 47, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvam, L.; Eide, A.H.; Vik, K. Understanding Experiences of Participation among Men and Women with Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain in Vocational Rehabilitation. Work 2013, 45, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Östlund, G.; Cedersund, E.; Hensing, G.; Alexanderson, K. Domestic Strain: A Hindrance in Rehabilitation? Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2004, 18, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooftman, W.E.; Westerman, M.J.; van der Beek, A.J.; Bongers, P.M.; van Mechelen, W. What Makes Men and Women with Musculoskeletal Complaints Decide They Are Too Sick to Work? Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2008, 34, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loisel, P.; Anema, J.R. (Eds.) Handbook of Work Disability: Prevention and Management; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loisel, P.; Buchbinder, R.; Hazard, R.; Keller, R.; Scheel, I.; van Tulder, M.; Webster, B. Prevention of Work Disability Due to Musculoskeletal Disorders: The Challenge of Implementing Evidence. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2005, 15, 507–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkhoff, C.M.; Hawker, G.A.; Kreder, H.J.; Glazier, R.H.; Mahomed, N.N.; Wright, J.G. The Effect of Patients’ Sex on Physicians’ Recommendations for Total Knee Arthroplasty. CMAJ 2008, 178, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, D.E.; Tarzian, A.J. The Girl Who Cried Pain: A Bias against Women in the Treatment of Pain. J. Law. Med. Ethics 2001, 29, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, J.A.; Patel, V.; Varela, N.A. Gender Disparities in Health Care. Mt. Sinai J. Med. A J. Transl. Pers. Med. 2012, 79, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippel, K.; Bienvenu, C. Les Dommages Fantômes: L’indemnisation Des Victimes de Lésions Professionnelles Pour l’incapacité d’effectuer Le Travail Domestique. Les Cah. Droit 2005, 36, 161–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté, D.; Coutu, M.-F. A Critical Review of Gender Issues in Understanding Prolonged Disability Related to Musculoskeletal Pain: How Are They Relevant to Rehabilitation? Disabil. Rehabil. 2010, 32, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauvin, N.; Freeman, A.; Côté, N.; Biron, C.; Duchesne, A.; Allaire, É. Une Démarche Paritaire de Prévention pour Contrer les Effets du Travail Émotionnellement Exigeant dans les Centres Jeunesse; Institut de recherche Robert-Sauvé en santé et en sécurité du travail: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ziebart, C.; Dabbagh, A.; Reischl, S.; Furtado, R.; MacDermid, J.C. Reporting of Sex and Gender in Randomized Controlled Trials of Rehabilitation Treated Distal Radius Fractures: A Systematic Review. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2025, 106, 1402–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, G.; Bobos, P.; Walton, D.M.; Miller, J.; Pedlar, D.; MacDermid, J.C. Reporting of Sex and Gender in Clinical Trials of Opioids and Rehabilitation in Military and Veterans with Chronic Pain. J. Mil. Veteran Fam. Health 2023, 9, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research Question/Conceptual Framework | Yes | Partially | No | N/A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The study clearly articulates sex or gender differences/issues that are relevant to the research question or context, e.g., epidemiology, risk factors and differential outcomes. | ||||

| The study discusses a theoretical conceptualization of sex/gender. | ||||

| The study clearly articulates a sex/gender research question as a primary or secondary research question, or states that the purpose includes controlling for/measuring the effect of sex/gender in the primary research question. | ||||

| Study Design | ||||

| Sex/gender and diverse populations of men and women are considered in sampling, inclusion and exclusion criteria (e.g., including parental leave, family leave or preventive withdrawal related to pregnancy). | ||||

| The study describes the recruitment strategies to accrue the appropriate sample of men and women. | ||||

| Measures of exposure/covariates are not gender-biased. | ||||

| The study describes how sex and gender were measured, and measures were appropriate. | ||||

| Choice of outcome measures or diagnostic/validation tests is not gender-biased. | ||||

| Analysis | ||||

| A description of how sex/gender are handled is stated in the data analysis plan (sex-disaggregated or stratified analyses, pathway modeling, treatment of sex and gender variables). | ||||

| Sex and gender are considered at an individual, organizational/system and/or societal level (e.g., gender relations and socially constructed roles). | ||||

| If applicable, potential interactions/confounding between sex and gender are considered/tested. | ||||

| The validity of the results for men and women is tested. | ||||

| Interpretation | ||||

| The extent to which the conclusions are valid for men and women is stated. | ||||

| The extent to which the conclusions are valid across gender-diverse populations is stated. | ||||

| Potential confounding, interaction and/or interplay between sex and gender are considered. | ||||

| How the results may need to be applied/translated based on sex/gender is considered. | ||||

| Overall Assessment: Are sex and gender adequately addressed in the study? | ||||

| Comments |

| Concepts | Ahlgren and Hammarström, 2000 [93] | Liedberg and Henriksson, 2002 [94] (Study on Women with FM) | Östlund et al. 2004 [96] | Kvam et al. 2013 [95] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic responsibilities | x | x | x | x |

| x | x | x | x |

| x | x | x | |

| x | x | ||

| Social support | x | x | x | |

| x | x | ||

| x | |||

| x | x | ||

| x | x | ||

| x | |||

| x | |||

| Working conditions | x | x | ||

| x | x | ||

| x | |||

| x | |||

| x | |||

| Gender-biased attitudes and behaviors of gatekeepers | x | x | x | |

| x | x | ||

| x | x | ||

| Work role and identity | x | x | x | |

| x | x | x | |

| x | x | ||

| Gender differences in injured workers’ expectations, attitudes or beliefs | x | |||

| x | |||

| x | |||

| Transportation to work | x | |||

| x | |||

| x | |||

| x |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stock, S.; Nicolakakis, N.; Cullen, K.; Dionne, C.E.; Franche, R.-L.; Lederer, V.; MacDermid, J.C.; MacEachen, E.; Messing, K.; Nastasia, I. What Are the Determinants of the Sex/Gender Difference in Duration of Work Absence for Musculoskeletal Disorders? A Mixed-Studies Systematic Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3228. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243228

Stock S, Nicolakakis N, Cullen K, Dionne CE, Franche R-L, Lederer V, MacDermid JC, MacEachen E, Messing K, Nastasia I. What Are the Determinants of the Sex/Gender Difference in Duration of Work Absence for Musculoskeletal Disorders? A Mixed-Studies Systematic Review. Healthcare. 2025; 13(24):3228. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243228

Chicago/Turabian StyleStock, Susan, Nektaria Nicolakakis, Kimberley Cullen, Clermont E. Dionne, Renée-Louise Franche, Valérie Lederer, Joy C. MacDermid, Ellen MacEachen, Karen Messing, and Iuliana Nastasia. 2025. "What Are the Determinants of the Sex/Gender Difference in Duration of Work Absence for Musculoskeletal Disorders? A Mixed-Studies Systematic Review" Healthcare 13, no. 24: 3228. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243228

APA StyleStock, S., Nicolakakis, N., Cullen, K., Dionne, C. E., Franche, R.-L., Lederer, V., MacDermid, J. C., MacEachen, E., Messing, K., & Nastasia, I. (2025). What Are the Determinants of the Sex/Gender Difference in Duration of Work Absence for Musculoskeletal Disorders? A Mixed-Studies Systematic Review. Healthcare, 13(24), 3228. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243228