Metformin-Enhanced Digital Therapeutics for the Affordable Primary Prevention of Diabetes and Cardiovascular Diseases: Advancing Low-Cost Solutions for Lifestyle-Related Chronic Disorders

Abstract

1. Introduction

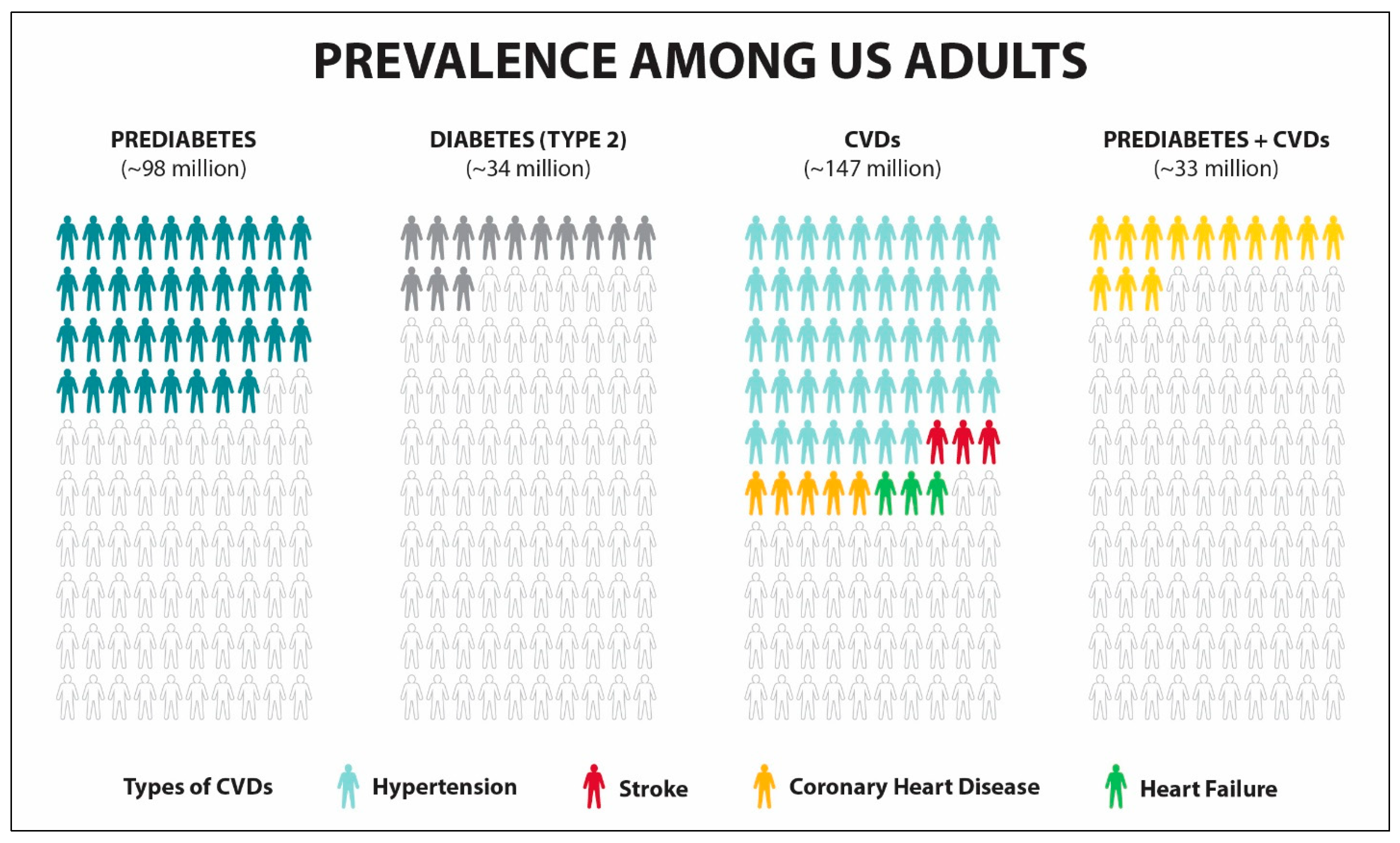

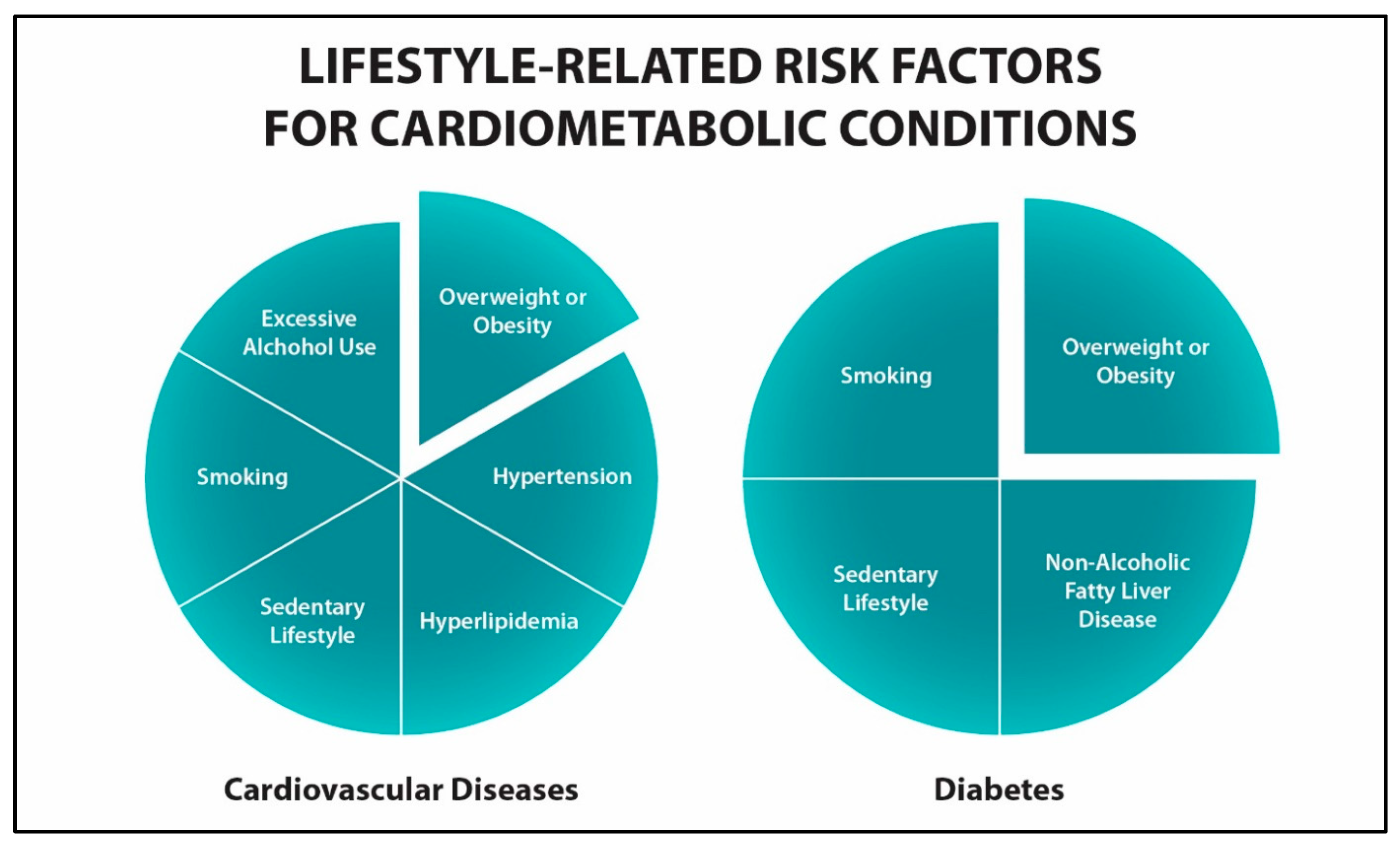

2. Chronic Disease Prevention

3. Digital Health Technologies for Diabetes and CVDs

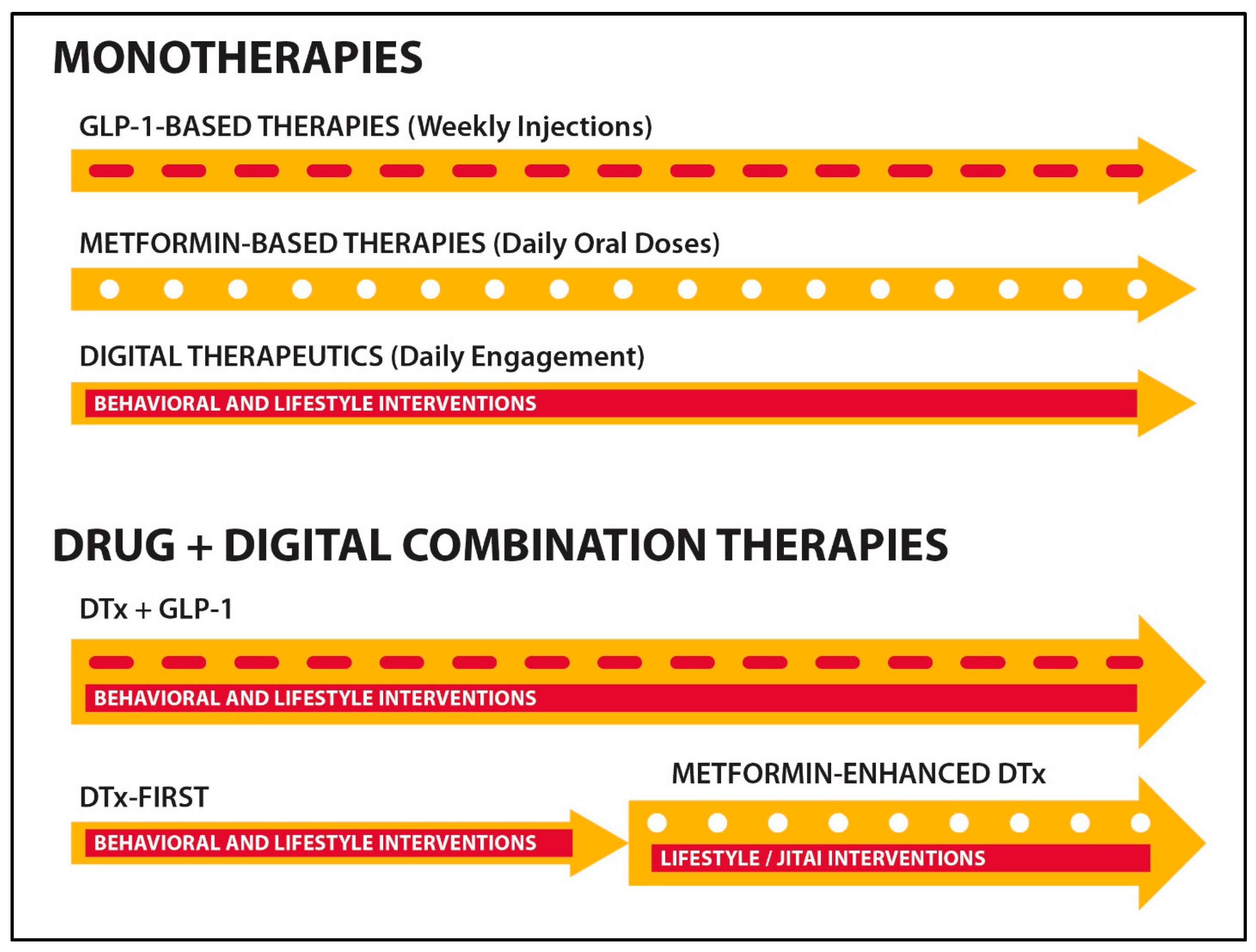

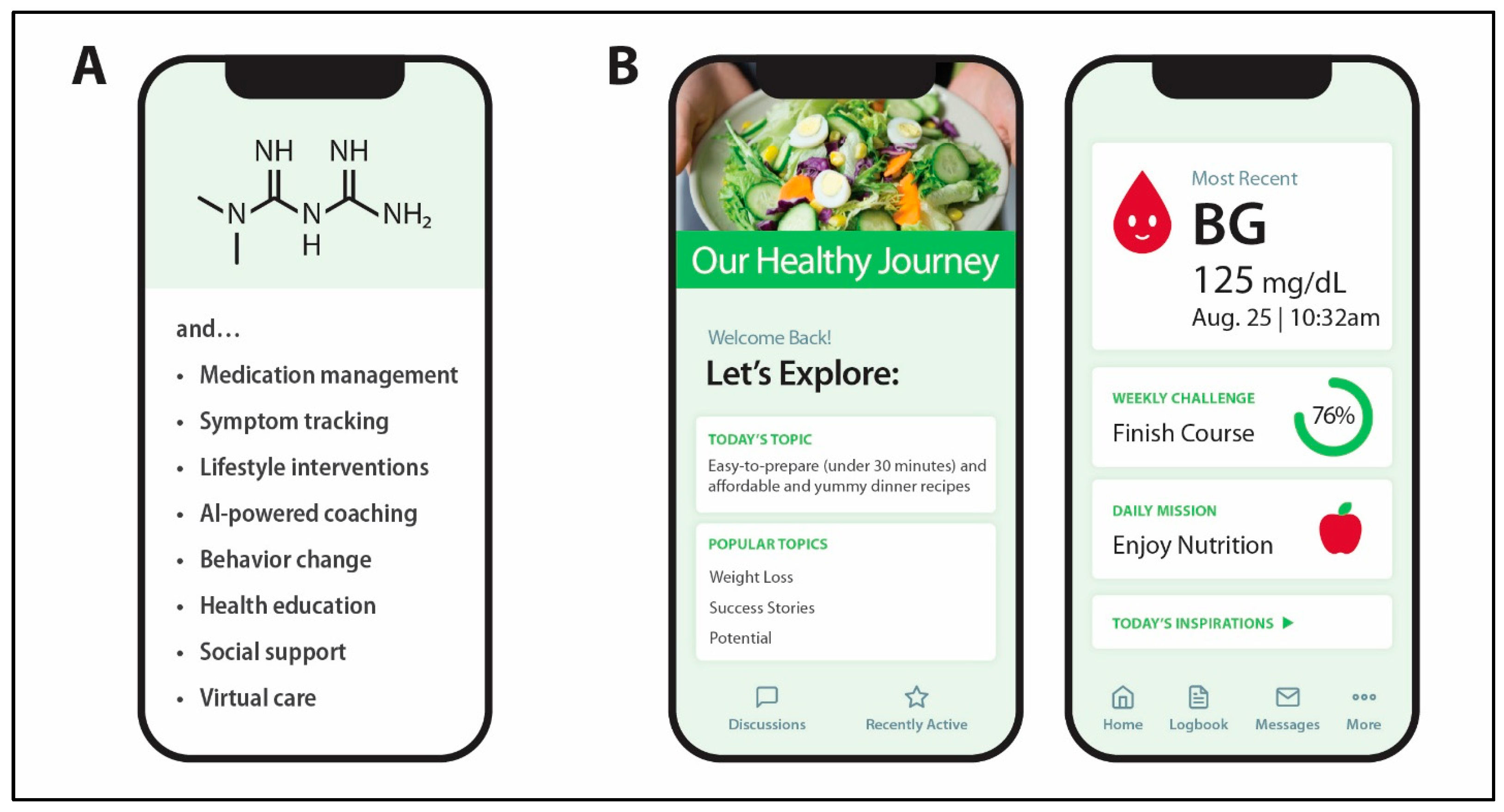

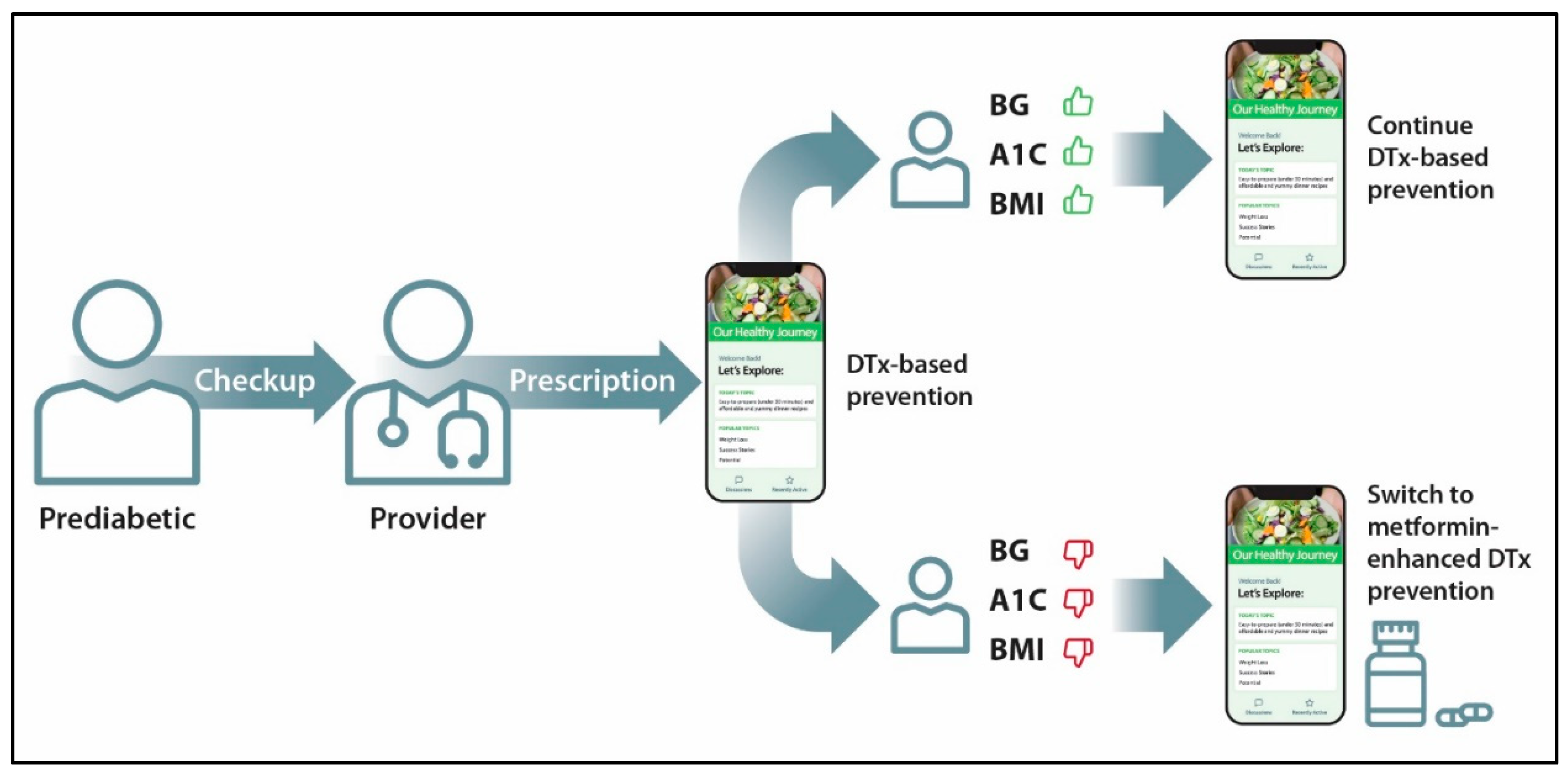

4. Integrating Digital Health and Pharmaceutical Drugs

- Does the PDURS provide a function that is essential to the safe and effective use of the product?

- Is there evidence that supports the clinical benefits of the PDURS?

- Does the PDURS rely on data directly transferred from the device constituent part of a combination product?

5. Low-Cost Primary Prevention of Diabetes and CVDs

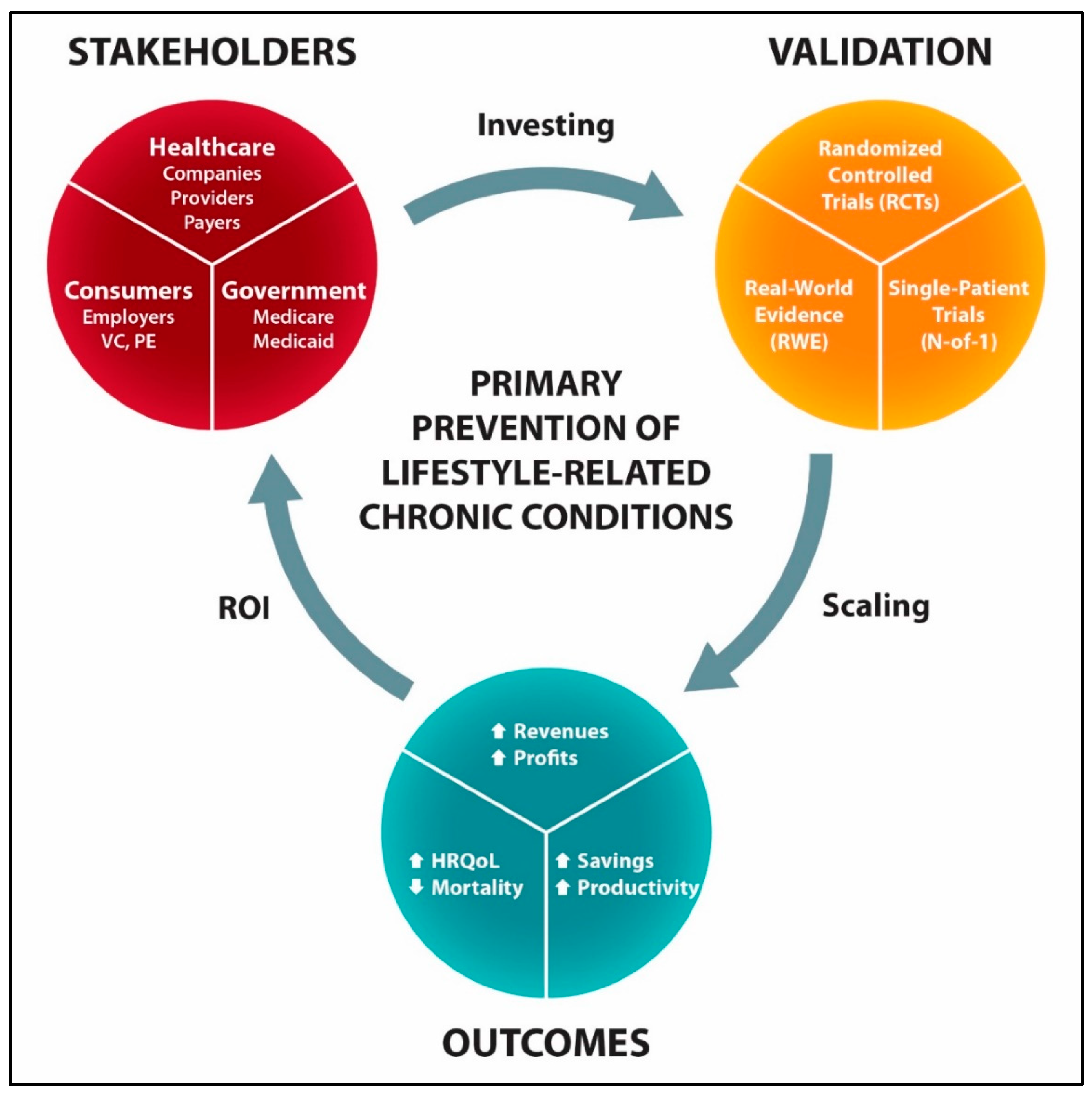

6. Incentives for Innovating the Primary Prevention of Lifestyle-Related Chronic Diseases

- Reduced development risk, since the relevant existing health technologies (digital health platforms and metformin) are backed by real-world evidence regarding their effectiveness and safety.

- Speed to market, since digital health technologies offer early revenue generation as compared to traditional drug-based development.

- Early market share favors growing long-term relationships with consumers and commercial partnerships that support wellness and lifestyle medicine (e.g., wearables).

- Low-cost prevention mitigates socioeconomic barriers to care, enabling adoption through private- and government-sponsored programs at scale.

- Decreasing profit margins for payers and healthcare systems from increasing utilization of costly GLP1RA-based drugs and ultra-premium specialty treatments, e.g., CRISPR gene-editing and cell-based therapeutics.

- The cost-related barriers of GLP-1 based drugs even after the loss of exclusivity in 2032, assuming 74% discount for generic drug prices [163].

- Obstacles of the government-based diabetes prevention program including overwhelming requirements, challenges in receiving Medicare designation and reimbursements, insufficient payments for the Medicare Advantage plans, and others [164].

7. Limitations and Challenges

8. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bauer, U.E.; Briss, P.A.; Goodman, R.A.; Bowman, B.A. Prevention of chronic disease in the 21st century: Elimination of the leading preventable causes of premature death and disability in the USA. Lancet 2014, 384, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boersma, P.; Black, L.I.; Ward, B.W. Prevalence of Multiple Chronic Conditions Among US Adults, 2018. Prev. Chronic. Dis. 2020, 17, E106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.S.; Aday, A.W.; Allen, N.B.; Almarzooq, Z.I.; Anderson, C.A.M.; Arora, P.; Avery, C.L.; Baker-Smith, C.M.; Bansal, N.; Beaton, A.Z.; et al. 2025 Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics: A Report of US and Global Data from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2025, 151, e41–e660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Prediabetes: Could It Be You? Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/communication-resources/prediabetes-statistics.html (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- CDC. A Report Card: Diabetes in the United States. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/communication-resources/diabetes-statistics.html (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Neupane, S.; Florkowski, W.J.; Dhakal, C. Trends and Disparities in Diabetes Prevalence in the United States from 2012 to 2022. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2024, 67, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, W.H.; Tyndall, B.D.; Duru, O.K.; Moin, T.; McEwen, L.N.; Shao, H.; Ackermann, R.T.; Jacobs, S.R.; Neuwahl, S.; Kuo, S.; et al. Real-World Interventions for Type 2 Diabetes Prevention (REALITY): A Multisite Study to Assess the Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of the National Diabetes Prevention Program. AJPM Focus 2025, 4, 100401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ely, E.K.; Gruss, S.M.; Luman, E.T.; Gregg, E.W.; Ali, M.K.; Nhim, K.; Rolka, D.B.; Albright, A.L. A National Effort to Prevent Type 2 Diabetes: Participant-Level Evaluation of CDC’s National Diabetes Prevention Program. Diabetes Care 2017, 40, 1331–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, M.J.; Ng, B.P.; Lloyd, K.; Reynolds, J.; Ely, E.K. Delivering the National Diabetes Prevention Program: Assessment of Enrollment in In-Person and Virtual Organizations. J. Diabetes Res. 2022, 2022, 2942918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brush, J.E., Jr.; Lu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Asher, J.R.; Li, S.X.; Sawano, M.; Young, P.; Schulz, W.L.; Anderson, M.; Burrows, J.S.; et al. Hypertension Trends and Disparities Over 12 Years in a Large Health System: Leveraging the Electronic Health Records. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e033253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joynt Maddox, K.E.; Elkind, M.S.V.; Aparicio, H.J.; Commodore-Mensah, Y.; de Ferranti, S.D.; Dowd, W.N.; Hernandez, A.F.; Khavjou, O.; Michos, E.D.; Palaniappan, L.; et al. Forecasting the Burden of Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke in the United States Through 2050-Prevalence of Risk Factors and Disease: A Presidential Advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2024, 150, e65–e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAulay, V.; Deary, I.J.; Frier, B.M. Symptoms of hypoglycaemia in people with diabetes. Diabet. Med. 2001, 18, 690–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.T.; Rayner, C.K.; Jones, K.L.; Talley, N.J.; Horowitz, M. Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Diabetes: Prevalence, Assessment, Pathogenesis, and Management. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atlantis, E.; Fahey, P.; Foster, J. Collaborative care for comorbid depression and diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e004706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodkinson, A.; Zhou, A.; Johnson, J.; Geraghty, K.; Riley, R.; Zhou, A.; Panagopoulou, E.; Chew-Graham, C.A.; Peters, D.; Esmail, A. Associations of physician burnout with career engagement and quality of patient care: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2022, 378, e070442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, S.V. The High Cost of Insulin in the United States: An Urgent Call to Action. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2020, 95, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Gellad, W.F. Origins of the Crisis in Insulin Affordability and Practical Advice for Clinicians on Using Human Insulin. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2020, 20, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Selvin, E. Cost-Related Insulin Rationing in US Adults Younger Than 65 Years with Diabetes. JAMA 2023, 329, 1700–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Shao, H.; Fonseca, V.; Shi, L. Exacerbation of financial burden of insulin and overall glucose-lowing medications among uninsured population with diabetes. J. Diabetes 2023, 15, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Y.; Valero-Elizondo, J.; Ali, H.J.; Pandey, A.; Cainzos-Achirica, M.; Krumholz, H.M.; Nasir, K.; Khera, R. Out-of-Pocket Annual Health Expenditures and Financial Toxicity from Healthcare Costs in Patients with Heart Failure in the United States. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e022164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, D.J. GLP-1-based therapies for diabetes, obesity and beyond. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2025, 24, 631–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Zheng, S.L.; Ye, X.L.; Shi, J.N.; Zheng, X.W.; Pan, H.S.; Zhang, Y.W.; Yang, X.L.; Huang, P. Cost-effectiveness analysis of 4 GLP-1RAs in the treatment of obesity in a US setting. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, J.H.; Laiteerapong, N.; Huang, E.S.; Kim, D.D. Lifetime Health Effects and Cost-Effectiveness of Tirzepatide and Semaglutide in US Adults. JAMA Health Forum 2025, 6, e245586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsipas, S.; Khan, T.; Loustalot, F.; Myftari, K.; Wozniak, G. Spending on Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists Among US Adults. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e252964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, E.D.; Lin, J.; Mahoney, T.; Ume, N.; Yang, G.; Gabbay, R.A.; ElSayed, N.A.; Bannuru, R.R. Economic Costs of Diabetes in the U.S. in 2022. Diabetes Care 2023, 47, 26–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birger, M.; Kaldjian, A.S.; Roth, G.A.; Moran, A.E.; Dieleman, J.L.; Bellows, B.K. Spending on Cardiovascular Disease and Cardiovascular Risk Factors in the United States: 1996 to 2016. Circulation 2021, 144, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, H.; Graf, M. The Costs of Chronic Disease in the US; The Milken Institute: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Keehan, S.P.; Madison, A.J.; Poisal, J.A.; Cuckler, G.A.; Smith, S.D.; Sisko, A.M.; Fiore, J.A.; Rennie, K.E. National Health Expenditure Projections, 2024–2033: Despite Insurance Coverage Declines, Health To Grow As Share Of GDP. Health Aff. 2025, 44, 776–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, S.H.; Byrne, C.D. Risk factors for diabetes and coronary heart disease. BMJ 2006, 333, 1009–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceriello, A.; Prattichizzo, F. Variability of risk factors and diabetes complications. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2021, 20, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Wilson, P.W.; Kannel, W.B. Beyond established and novel risk factors: Lifestyle risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2008, 117, 3031–3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chai, X.; Wang, Y.; Yin, X.; Huang, X.; Gong, Q.; Zhang, J.; Shao, R.; Li, G. Effectiveness of Different Intervention Modes in Lifestyle Intervention for the Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes and the Reversion to Normoglycemia in Adults with Prediabetes: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e63975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagastume, D.; Siero, I.; Mertens, E.; Cottam, J.; Colizzi, C.; Peñalvo, J.L. The effectiveness of lifestyle interventions on type 2 diabetes and gestational diabetes incidence and cardiometabolic outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of evidence from low- and middle-income countries. eClinicalMedicine 2022, 53, 101650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hei, Y.; Xie, Y. Effects of exercise combined with different dietary interventions on cardiovascular health a systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2025, 25, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 9. Pharmacologic Approaches to Glycemic Treatment: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, S158–S178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 10. Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, S179–S218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Jones, D.M.; Allen, N.B.; Anderson, C.A.M.; Black, T.; Brewer, L.C.; Foraker, R.E.; Grandner, M.A.; Lavretsky, H.; Perak, A.M.; Sharma, G.; et al. Life’s Essential 8: Updating and Enhancing the American Heart Association’s Construct of Cardiovascular Health: A Presidential Advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022, 146, e18–e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell-Wiley, T.M.; Baumer, Y.; Baah, F.O.; Baez, A.S.; Farmer, N.; Mahlobo, C.T.; Pita, M.A.; Potharaju, K.A.; Tamura, K.; Wallen, G.R. Social Determinants of Cardiovascular Disease. Circ. Res. 2022, 130, 782–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndebele, P.; Krisko, P.; Bari, I.; Paichadze, N.; Hyder, A.A. Evaluating industry attempts to influence public health: Applying an ethical framework in understanding commercial determinants of health. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 976898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uthman, O.A.; Court, R.; Enderby, J.; Nduka, C.; Al-Khudairy, L.; Anjorin, S.; Mistry, H.; Melendez-Torres, G.J.; Taylor-Phillips, S.; Clarke, A. Identifying optimal primary prevention interventions for major cardiovascular disease events and all-cause mortality: A systematic review and hierarchical network meta-analysis of RCTs. Health Technol. Assess. 2025, 29, 75–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.L.; Roddick, A.J. Association of Aspirin Use for Primary Prevention with Cardiovascular Events and Bleeding Events: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA 2019, 321, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zushin, P.-J.H.; Wu, J.C. Evaluating the benefits of the early use of GLP-1 receptor agonists. Lancet 2025, 405, 181–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Zhang, M.; Cao, Q.; Lin, L.; Lu, J.; Bi, Y.; Chen, Y. Efficacy of GLP-1 Receptor Agonist-Based Therapies on Cardiovascular Events and Cardiometabolic Parameters in Obese Individuals Without Diabetes: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Diabetes 2025, 17, e70082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalayci, A.; Januzzi, J.L.; Mitsunami, M.; Tanboga, I.H.; Karabay, C.Y.; Gibson, C.M. Clinical features modifying the cardiovascular benefits of GLP-1 receptor agonists: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 2025, 11, 552–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Rangel, E.; Inzucchi, S.E. Metformin: Clinical use in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2017, 60, 1586–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayedali, E.; Yalin, A.E.; Yalin, S. Association between metformin and vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with type 2 diabetes. World J. Diabetes 2023, 14, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelwahab, O.A.; Abdelaziz, A.; Diab, S.; Khazragy, A.; Elboraay, T.; Fayad, T.; Diab, R.A.; Negida, A. Efficacy of different routes of vitamin B12 supplementation for the treatment of patients with vitamin B12 deficiency: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2024, 193, 1621–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inzucchi, S.E.; Lipska, K.J.; Mayo, H.; Bailey, C.J.; McGuire, D.K. Metformin in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review. JAMA 2014, 312, 2668–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, C.; Wang, G.; Liu, N.; Andrikopoulos, S.; Zajac, J.D.; Ekinci, E.I. Metformin: Time to review its role and safety in chronic kidney disease. Med. J. Aust. 2019, 211, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverii, G.A. Optimizing metformin therapy in practice: Tailoring therapy in specific patient groups to improve tolerability, efficacy and outcomes. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2024, 26, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knowler, W.C.; Doherty, L.; Edelstein, S.L.; Bennett, P.H.; Dabelea, D.; Hoskin, M.; Kahn, S.E.; Kalyani, R.R.; Kim, C.; Pi-Sunyer, F.X.; et al. Long-term effects and effect heterogeneity of lifestyle and metformin interventions on type 2 diabetes incidence over 21 years in the US Diabetes Prevention Program randomised clinical trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025, 13, 469–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousavi, S.S.; Namayandeh, S.M.; Fallahzadeh, H.; Rahmanian, M.; Mollahosseini, M. Comparing the effectiveness of metformin with lifestyle modification for the primary prevention of type II diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2023, 23, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, S.; Wang, X.; Dong, L.; Li, Q.; Ren, W.; Li, Y.; Bai, J.; Gong, Q.; et al. Safety and effectiveness of metformin plus lifestyle intervention compared with lifestyle intervention alone in preventing progression to diabetes in a Chinese population with impaired glucose regulation: A multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2023, 11, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aroda, V.R.; Ratner, R.E. Metformin and Type 2 Diabetes Prevention. Diabetes Spectr. 2018, 31, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apolzan, J.W.; Venditti, E.M.; Edelstein, S.L.; Knowler, W.C.; Dabelea, D.; Boyko, E.J.; Pi-Sunyer, X.; Kalyani, R.R.; Franks, P.W.; Srikanthan, P.; et al. Long-Term Weight Loss with Metformin or Lifestyle Intervention in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2019, 170, 682–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monami, M.; Candido, R.; Pintaudi, B.; Targher, G.; Mannucci, E.; Mannucci, E.; Candido, R.; Pintaudi, B.; Targher, G.; Delle Monache, L.; et al. Effect of metformin on all-cause mortality and major adverse cardiovascular events: An updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2021, 31, 699–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Lei, M.; Ke, G.; Huang, X.; Peng, X.; Zhong, L.; Fu, P. Metformin Use and Risk of All-Cause Mortality and Cardiovascular Events in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 559446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamanna, C.; Monami, M.; Marchionni, N.; Mannucci, E. Effect of metformin on cardiovascular events and mortality: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2011, 13, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneto, H.; Kimura, T.; Obata, A.; Shimoda, M.; Kaku, K. Multifaceted Mechanisms of Action of Metformin Which Have Been Unraveled One after Another in the Long History. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foretz, M.; Guigas, B.; Bertrand, L.; Pollak, M.; Viollet, B. Metformin: From mechanisms of action to therapies. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 953–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foretz, M.; Guigas, B.; Viollet, B. Metformin: Update on mechanisms of action and repurposing potential. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2023, 19, 460–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristófi, R.; Eriksson, J.W. Metformin as an anti-inflammatory agent: A short review. J. Endocrinol. 2021, 251, R11–R22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, D.J. The benefits of GLP-1 drugs beyond obesity. Science 2024, 385, 258–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.K. Mechanisms of action and therapeutic applications of GLP-1 and dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonists. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1431292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zong, Y.; Ma, Y.; Tian, Y.; Pang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Gao, J. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor: Mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hostalek, U.; Gwilt, M.; Hildemann, S. Therapeutic Use of Metformin in Prediabetes and Diabetes Prevention. Drugs 2015, 75, 1071–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moin, T.; Schmittdiel, J.A.; Flory, J.H.; Yeh, J.; Karter, A.J.; Kruge, L.E.; Schillinger, D.; Mangione, C.M.; Herman, W.H.; Walker, E.A. Review of Metformin Use for Type 2 Diabetes Prevention. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2018, 55, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, D.; Ayesha, I.E.; Monson, N.R.; Klair, N.; Patel, U.; Saxena, A.; Hamid, P.; Ayesha, I.E.; Hamid, P.F. The effectiveness of metformin in diabetes prevention: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cureus 2023, 15, e46108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowler, W.C.; Barrett-Connor, E.; Fowler, S.E.; Hamman, R.F.; Lachin, J.M.; Walker, E.A.; Nathan, D.M. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- le Roux, C.W.; Astrup, A.; Fujioka, K.; Greenway, F.; Lau, D.C.W.; Van Gaal, L.; Ortiz, R.V.; Wilding, J.P.H.; Skjøth, T.V.; Manning, L.S.; et al. 3 years of liraglutide versus placebo for type 2 diabetes risk reduction and weight management in individuals with prediabetes: A randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet 2017, 389, 1399–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jastreboff, A.M.; le Roux, C.W.; Stefanski, A.; Aronne, L.J.; Halpern, B.; Wharton, S.; Wilding, J.P.H.; Perreault, L.; Zhang, S.; Battula, R.; et al. Tirzepatide for Obesity Treatment and Diabetes Prevention. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 958–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perreault, L.; Davies, M.; Frias, J.P.; Laursen, P.N.; Lingvay, I.; Machineni, S.; Varbo, A.; Wilding, J.P.H.; Wallenstein, S.O.R.; le Roux, C.W. Changes in Glucose Metabolism and Glycemic Status with Once-Weekly Subcutaneous Semaglutide 2.4 mg Among Participants with Prediabetes in the STEP Program. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, 2396–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-J.; Herder, C.; Xie, R.; Brenner, H.; Schöttker, B. Comparison of the metabolic profiles and their cardiovascular event risks of metformin users versus insulin users. A cohort study of people with type 2 diabetes from the UK Biobank. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2025, 222, 112108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Liu, H.; Wen, X.; Peng, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhao, L. Effects of metformin on blood pressure in nondiabetic patients: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Hypertens. 2017, 35, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahardoust, M.; Mousavi, S.; Yariali, M.; Haghmoradi, M.; Hadaegh, F.; Khalili, D.; Delpisheh, A. Effect of metformin (vs. placebo or sulfonylurea) on all-cause and cardiovascular mortality and incident cardiovascular events in patients with diabetes: An umbrella review of systematic reviews with meta-analysis. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2024, 23, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillai, A.A.; Melo, L.; Frishman, W.H.; Aronow, W.S. The Effects of Metformin on Weight Loss, Cardiovascular Health, and Longevity. Cardiol. Rev. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, D.A.; Presume, J.; de Araújo Gonçalves, P.; Almeida, M.S.; Mendes, M.; Ferreira, J. Association Between the Magnitude of Glycemic Control and Body Weight Loss with GLP-1 Receptor Agonists and Risk of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analyses of Randomized Diabetes Cardiovascular Outcomes Trials. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2025, 39, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferhatbegović, L.; Mršić, D.; Macić-Džanković, A. The benefits of GLP1 receptors in cardiovascular diseases. Front. Clin. Diabetes Healthc. 2023, 4, 1293926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badve, S.V.; Bilal, A.; Lee, M.M.Y.; Sattar, N.; Gerstein, H.C.; Ruff, C.T.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Rossing, P.; Bakris, G.; Mahaffey, K.W.; et al. Effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists on kidney and cardiovascular disease outcomes: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025, 13, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira-Gomes, D.; Pingili, A.; Inglis, S.; Mandras, S.A.; Loro-Ferrer, J.F.; daSilva-deAbreu, A. Impact of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists on hypertension management: A narrative review. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2025, 40, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi-Sunyer, X.; Astrup, A.; Fujioka, K.; Greenway, F.; Halpern, A.; Krempf, M.; Lau, D.C.; le Roux, C.W.; Violante Ortiz, R.; Jensen, C.B.; et al. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of 3.0 mg of Liraglutide in Weight Management. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilding, J.P.H.; Batterham, R.L.; Calanna, S.; Davies, M.; Van Gaal, L.F.; Lingvay, I.; McGowan, B.M.; Rosenstock, J.; Tran, M.T.D.; Wadden, T.A.; et al. Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults with Overweight or Obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 989–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFronzo, R.; Fleming, G.A.; Chen, K.; Bicsak, T.A. Metformin-associated lactic acidosis: Current perspectives on causes and risk. Metabolism 2016, 65, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infante, M.; Leoni, M.; Caprio, M.; Fabbri, A. Long-term metformin therapy and vitamin B12 deficiency: An association to bear in mind. World J. Diabetes 2021, 12, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juneja, D.; Nasa, P.; Jain, R. Metformin toxicity: A meta-summary of case reports. World J. Diabetes 2022, 13, 654–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.-H.; Tan, B.; Chin, Y.H.; Lee, E.C.Z.; Kong, G.; Chong, B.; Kueh, M.; Khoo, C.M.; Mehta, A.; Majety, P.; et al. Efficacy and safety of tirzepatide, GLP-1 receptor agonists, and other weight loss drugs in overweight and obesity: A network meta-analysis. Obesity 2024, 32, 840–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismaiel, A.; Scarlata, G.G.M.; Boitos, I.; Leucuta, D.-C.; Popa, S.-L.; Al Srouji, N.; Abenavoli, L.; Dumitrascu, D.L. Gastrointestinal adverse events associated with GLP-1 RA in non-diabetic patients with overweight or obesity: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Int. J. Obes. 2025, 49, 1946–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, A.; Chapman, R.; Shafai, G.; Maricich, Y.A. FDA regulations and prescription digital therapeutics: Evolving with the technologies they regulate. Front. Digit. Health 2023, 5, 1086219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, J.; Fang, Q.; Jiao, X.; Xiang, P.; Ma, J.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; He, Y.; Li, Y.; He, Z.; et al. Approved trends and product characteristics of digital therapeutics in four countries. npj Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakhan, S.E. The Composite Digital Therapeutic Index (cDTI): A Multidimensional Framework and Proof-of-Concept Application to FDA-Authorized Treatments. Cureus 2025, 17, e83886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spatz, E.S.; Ginsburg, G.S.; Rumsfeld, J.S.; Turakhia, M.P. Wearable digital health technologies for monitoring in cardiovascular medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chengyu, Z.; Xueyan, H.; Ying, F. Research on disease management of chronic disease patients based on digital therapeutics: A scoping review. Digit. Health 2024, 10, 20552076241297064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shomali, M.; Mora, P.; Aleppo, G.; Peeples, M.; Kumbara, A.; MacLeod, J.; Iyer, A. The critical elements of digital health in diabetes and cardiometabolic care. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1469471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhan, S.E. Decoding FDA Labeling of Prescription Digital Therapeutics: A Cross-Sectional Regulatory Study. Cureus 2025, 17, e84468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, S.; Gallagher, S.; Andrews, T.; Ashall-Payne, L.; Humphreys, L.; Leigh, S. The effectiveness of digital health technologies for patients with diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. Front. Clin. Diabetes Healthc. 2022, 3, 936752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avoke, D.; Elshafeey, A.; Weinstein, R.; Kim, C.H.; Martin, S.S. Digital Health in Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease. Endocr. Res. 2024, 49, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle-Delgado, K.; Chamberlain, J.J. Use of diabetes-related applications and digital health tools by people with diabetes and their health care providers. Clin. Diabetes 2020, 38, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathioudakis, N.; Lalani, B.; Abusamaan, M.S.; Alderfer, M.; Alver, D.; Dobs, A.; Kane, B.; McGready, J.; Riekert, K.; Ringham, B.; et al. An AI-Powered Lifestyle Intervention vs Human Coaching in the Diabetes Prevention Program: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2025, e2519563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Y.; Mohamad, E.; Azlan, A.A.; Zhang, C.; Ma, Y.; Wu, A. Digital Health Solutions for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e64981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stowell, M.; Dobson, R.; Garner, K.; Baig, M.; Nehren, N.; Whittaker, R. Digital interventions for self-management of prediabetes: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Ward, T.; Sudimack, A.; Cox, S.; Ballreich, J. Cost-effectiveness analysis of a digital Diabetes Prevention Program (dDPP) in prediabetic patients. J. Telemed. Telecare 2025, 31, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arriazola, J.; Wollen, J.; Davis, S.; Wang, E.M.; Tran, G.; Rosario, N. Review of Over the Counter and Prescription Continuous Glucose Monitoring. J. Pharm. Pract. 2025, 38, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamanna, P.; Joshi, S.; Thajudeen, M.; Shah, L.; Poon, T.; Mohamed, M.; Mohammed, J. Personalized nutrition in type 2 diabetes remission: Application of digital twin technology for predictive glycemic control. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1485464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari, A.A.; Gu, K.; Srinivas, V.; Yu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Paruchuri, A.; He, Q.; Palangi, H.; Hammerquist, N. The anatomy of a personal health agent. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.20148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, C.; Baldwin, M.; Keogh, A.; Caulfield, B.; Argent, R. Keeping pace with wearables: A living umbrella review of systematic reviews evaluating the accuracy of consumer wearable technologies in health measurement. Sports Med. 2024, 54, 2907–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattison, G.; Canfell, O.; Forrester, D.; Dobbins, C.; Smith, D.; Töyräs, J.; Sullivan, C. The influence of wearables on health care outcomes in chronic disease: Systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e36690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, A.; Chico, T.J.A.; Jones, S.; Chaturvedi, N.; Hughes, A.D.; Orini, M. A guide to consumer-grade wearables in cardiovascular clinical care and population health for non-experts. npj Cardiovasc. Health 2025, 2, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, W.; Kirk, A.; Lennon, M.; Paxton, G. Exploring the Use of Fitbit Consumer Activity Trackers to Support Active Lifestyles in Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: A Mixed-Methods Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bliudzius, A.; Svaikeviciene, K.; Puronaite, R.; Kasiulevicius, V. Physical Activity Evaluation Using Activity Trackers for Type 2 Diabetes Prevention in Patients with Prediabetes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, T.; Olds, T.; Curtis, R.; Blake, H.; Crozier, A.J.; Dankiw, K.; Dumuid, D.; Kasai, D.; O’Connor, E.; Virgara, R.; et al. Effectiveness of wearable activity trackers to increase physical activity and improve health: A systematic review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Lancet Digit. Health 2022, 4, e615–e626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodkinson, A.; Kontopantelis, E.; Adeniji, C.; van Marwijk, H.; McMillian, B.; Bower, P.; Panagioti, M. Interventions Using Wearable Physical Activity Trackers Among Adults with Cardiometabolic Conditions: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2116382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, A.; Changolkar, S.; Patel, M.S. Wearable Devices to Monitor and Reduce the Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: Evidence and Opportunities. Annu. Rev. Med. 2021, 72, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuss, K.; Moore, K.; Nelson, T.; Li, K. Effects of motivational interviewing and wearable fitness trackers on motivation and physical activity: A systematic review. Am. J. Health Promot. 2021, 35, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfaye, L.; Wakeman, M.; Baskin, G.; Gruse, G.; Gregory, T.; Leahy, E.; Kendrick, B.; El-Toukhy, S. A feature-based qualitative assessment of smoking cessation mobile applications. PLoS Digit. Health 2024, 3, e0000658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacoviello, B.M.; Steinerman, J.R.; Klein, D.B.; Silver, T.L.; Berger, A.G.; Luo, S.X.; Schork, N.J. Clickotine, A Personalized Smartphone App for Smoking Cessation: Initial Evaluation. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2017, 5, e56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bricker, J.B.; Sullivan, B.; Mull, K.; Santiago-Torres, M.; Lavista Ferres, J.M. Conversational Chatbot for Cigarette Smoking Cessation: Results from the 11-Step User-Centered Design Development Process and Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2024, 12, e57318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulaj, G.; Ahern, M.M.; Kuhn, A.; Judkins, Z.S.; Bowen, R.C.; Chen, Y. Incorporating Natural Products, Pharmaceutical Drugs, Self-care and Digital/Mobile Health Technologies into Molecular-Behavioral Combination Therapies for Chronic Diseases. Curr. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016, 11, 128–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sverdlov, O.; van Dam, J.; Hannesdottir, K.; Thornton-Wells, T. Digital Therapeutics: An Integral Component of Digital Innovation in Drug Development. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 104, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biskupiak, Z.; Ha, V.V.; Rohaj, A.; Bulaj, G. Digital Therapeutics for Improving Effectiveness of Pharmaceutical Drugs and Biological Products: Preclinical and Clinical Studies Supporting Development of Drug + Digital Combination Therapies for Chronic Diseases. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, C.C.; Clough, S.S.; Minor, J.M.; Lender, D.; Okafor, M.C.; Gruber-Baldini, A. WellDoc mobile diabetes management randomized controlled trial: Change in clinical and behavioral outcomes and patient and physician satisfaction. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2008, 10, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maricich, Y.A.; Bickel, W.K.; Marsch, L.A.; Gatchalian, K.; Botbyl, J.; Luderer, H.F. Safety and efficacy of a prescription digital therapeutic as an adjunct to buprenorphine for treatment of opioid use disorder. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2021, 37, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulaj, G. Combining non-pharmacological treatments with pharmacotherapies for neurological disorders: A unique interface of the brain, drug-device, and intellectual property. Front. Neurol. 2014, 5, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afra, P.; Bruggers, C.S.; Sweney, M.; Fagatele, L.; Alavi, F.; Greenwald, M.; Huntsman, M.; Nguyen, K.; Jones, J.K.; Shantz, D.; et al. Mobile Software as a Medical Device (SaMD) for the Treatment of Epilepsy: Development of Digital Therapeutics Comprising Behavioral and Music-Based Interventions for Neurological Disorders. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, B.; Slomkowski, M.; Speier, A.; Rush, A.J.; Trivedi, M.H.; Lakhan, S.E.; Lawson, E.; Fahmy, M.; Carpenter, D.; Chen, D.; et al. A digital therapeutic (CT-152) as adjunct to antidepressant medication: A phase 3 randomized controlled trial (the Mirai study). J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 388, 119409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA. Regulatory Considerations for Prescription Drug Use-Related Software. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/regulatory-considerations-prescription-drug-use-related-software (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Hsia, J.; Guthrie, N.L.; Lupinacci, P.; Gubbi, A.; Denham, D.; Berman, M.A.; Bonaca, M.P. Randomized, Controlled Trial of a Digital Behavioral Therapeutic Application to Improve Glycemic Control in Adults with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, 2976–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.B.; Kim, G.; Jun, J.E.; Park, H.; Lee, W.J.; Hwang, Y.C.; Kim, J.H. An Integrated Digital Health Care Platform for Diabetes Management with AI-Based Dietary Management: 48-Week Results from a Randomized Controlled Trial. Diabetes Care 2023, 46, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toliver, J.C.; Divino, V.; Ng, C.D.; Wang, J. Real-World Weight Loss Among Patients Initiating Semaglutide 2.4 mg and Enrolled in WeGoTogether, a Digital Self-Support Application. Adv. Ther. 2025, 42, 5010–5022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, H.; Jabri, H.; Alshehhi, S.; Caccelli, M.; Debs, J.; Said, Y.; Kattan, J.; Almarzooqi, N.; Hashemi, A.; Almarzooqi, I. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists Combined with Personalized Digital Health Care for the Treatment of Metabolic Syndrome in Adults with Obesity: Retrospective Observational Study. Interact. J. Med. Res. 2025, 14, e63079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, H.; Huang, D.; Liu, V.; Ammouri, M.A.; Jacobs, C.; El-Osta, A. Impact of Digital Engagement on Weight Loss Outcomes in Obesity Management Among Individuals Using GLP-1 and Dual GLP-1/GIP Receptor Agonist Therapy: Retrospective Cohort Service Evaluation Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e69466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, W.J.; Hoog, M.; Mody, R.; Belger, M.; Pollock, R. Long-term cost-effectiveness analysis of tirzepatide versus semaglutide 1.0 mg for the management of type 2 diabetes in the United States. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2023, 25, 1292–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; Feldman, R.; Callaway Kim, K.; Rothenberger, S.; Korytkowski, M.; Hernandez, I.; Gellad, W.F. Evaluation of Out-of-Pocket Costs and Treatment Intensification with an SGLT2 Inhibitor or GLP-1 RA in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2317886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klepser, N.S.; Weber, E.S.; Li, L.; Fleischmann, K.E.; Masharani, U.; Park, M.; Max, W.B.; Yeboah, J.; Hunink, M.G.M.; Ferket, B.S. Adherence to GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors by out-of-pocket spending among Medicare beneficiaries with diabetes. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2025, 27, 5683–5693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrie, J.R. Metformin beyond type 2 diabetes: Emerging and potential new indications. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2024, 26 (Suppl. S3), 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echouffo-Tcheugui, J.B.; Perreault, L.; Ji, L.; Dagogo-Jack, S. Diagnosis and Management of Prediabetes: A Review. JAMA 2023, 329, 1206–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulaj, G.; Coleman, M.; Johansen, B.; Kraft, S.; Lam, W.; Phillips, K.; Rohaj, A. Redesigning Pharmacy to Improve Public Health Outcomes: Expanding Retail Spaces for Digital Therapeutics to Replace Consumer Products That Increase Mortality and Morbidity Risks. Pharmacy 2024, 12, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zand, A.; Ibrahim, K.; Patham, B. Prediabetes: Why Should We Care? Methodist DeBakey Cardiovasc. J. 2018, 14, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toro-Ramos, T.; Michaelides, A.; Anton, M.; Karim, Z.; Kang-Oh, L.; Argyrou, C.; Loukaidou, E.; Charitou, M.M.; Sze, W.; Miller, J.D. Mobile Delivery of the Diabetes Prevention Program in People with Prediabetes: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e17842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.L.; Ong, K.W.; Johal, J.; Han, C.Y.; Yap, Q.V.; Chan, Y.H.; Zhang, Z.P.; Chandra, C.C.; Thiagarajah, A.G.; Khoo, C.M. A Smartphone App-Based Lifestyle Change Program for Prediabetes (D’LITE Study) in a Multiethnic Asian Population: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 780567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, A.Y.; Xu, X.Y.; Chau, P.H.; Yu, Y.T.E.; Cheung, M.K.; Wong, C.K.; Fong, D.Y.; Wong, J.Y.; Lam, C.L. A Mobile App for Identifying Individuals with Undiagnosed Diabetes and Prediabetes and for Promoting Behavior Change: 2-Year Prospective Study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2018, 6, e10662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeem, Y.A.; Andriani, R.N.; Nabila, R.; Emelia, D.D.; Lazuardi, L.; Koesnanto, H. The Use of Mobile Health Interventions for Outcomes among Middle-Aged and Elderly Patients with Prediabetes: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, M.L.; McCarthy, C.; Bateman, M.T.; Simmons, D.; Prioli, K.M. Pharmacists improve diabetes outcomes: A randomized controlled trial. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2022, 62, 775–782.e773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, K.W.; Ng, C.M.; Chong, C.W.; Cheong, W.L.; Ng, Y.L.; Bell, J.S.; Lee, S.W.H. A digital health-supported and community pharmacy-based lifestyle intervention program for adults with pre-diabetes: A study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e083921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, S.; Sanchez Machado, M.; Alshahrouri, B.; Echeverri, J.I.; Rico, M.C.; Rao, A.D.; Ruchalski, C.; Barrero, C.A. Empowering Pharmacists in Type 2 Diabetes Care: Opportunities for Prevention, Counseling, and Therapeutic Optimization. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Ghani, M.; Abu-Farha, M.; Abdul-Ghani, T.; Chavez-Velazquez, A.; Merovci, A.; DeFronzo, R.A.; Alajmi, F.; Stern, M.; Al-Mulla, F. One-Hour Plasma Glucose Predicts the Progression from Normal Glucose Tolerance to Prediabetes. Diabetes Care 2025, 48, 1273–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagogo-Jack, S. Pathobiology of Prediabetes: Understanding and Interrupting Progressive Dysglycemia and Associated Complications. Diabetes 2025, 74, 2155–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babatunde, A.O.; Ogundijo, D.A.; Afolayan, A.-G.O.; Awosiku, O.V.; Aderohunmu, Z.O.; Oguntade, M.S.; Alao, U.H.; Oseni, A.O.; Akintola, A.A.; Amusat, O.A. Mobile health technologies in the prevention and management of hypertension: A scoping review. Digit. Health 2024, 10, 20552076241277172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnooh, G.; Alessa, T.; Hawley, M.; de Witte, L. The Use of Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) Mobile Apps for Supporting a Healthy Diet and Controlling Hypertension in Adults: Systematic Review. JMIR Cardio 2022, 6, e35876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Long, H. The Effect of Smartphone App–Based Interventions for Patients with Hypertension: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e21759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketola, E.; Sipilä, R.; Mäkelä, M. Effectiveness of individual lifestyle interventions in reducing cardiovascular disease and risk factors. Ann. Med. 2000, 32, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaminsky, L.A.; German, C.; Imboden, M.; Ozemek, C.; Peterman, J.E.; Brubaker, P.H. The importance of healthy lifestyle behaviors in the prevention of cardiovascular disease. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2022, 70, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, R.; Indraratna, P.; Lovell, N.; Ooi, S.-Y. Digital health technology in the prevention of heart failure and coronary artery disease. Cardiovasc. Digit. Health J. 2022, 3, S9–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neubeck, L.; Lowres, N.; Benjamin, E.J.; Freedman, S.B.; Coorey, G.; Redfern, J. The mobile revolution—Using smartphone apps to prevent cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2015, 12, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widmer, R.J.; Collins, N.M.; Collins, C.S.; West, C.P.; Lerman, L.O.; Lerman, A. Digital health interventions for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2015, 90, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, Y.; Hosaka, M.; Elnagar, N.; Satoh, M. Clinical significance of home blood pressure measurements for the prevention and management of high blood pressure. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2014, 41, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, R.B.; Orchard, T.J.; Crandall, J.P.; Boyko, E.J.; Budoff, M.; Dabelea, D.; Gadde, K.M.; Knowler, W.C.; Lee, C.G.; Nathan, D.M.; et al. Effects of Long-term Metformin and Lifestyle Interventions on Cardiovascular Events in the Diabetes Prevention Program and Its Outcome Study. Circulation 2022, 145, 1632–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Bhatia, R.; Sharma, G.; Dhanlika, D.; Vishnubhatla, S.; Singh, R.K.; Dash, D.; Tripathi, M.; Srivastava, M.V.P. Effect of yoga as add-on therapy in migraine (CONTAIN). Neurology 2020, 94, e2203–e2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leitner, J.; Chiang, P.-H.; Agnihotri, P.; Dey, S. The Effect of an AI-Based, Autonomous, Digital Health Intervention Using Precise Lifestyle Guidance on Blood Pressure in Adults with Hypertension: Single-Arm Nonrandomized Trial. JMIR Cardio 2024, 8, e51916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skalidis, I.; Maurizi, N.; Salihu, A.; Fournier, S.; Cook, S.; Iglesias, J.F.; Laforgia, P.; D’Angelo, L.; Garot, P.; Hovasse, T. Artificial Intelligence and Advanced Digital Health for Hypertension: Evolving Tools for Precision Cardiovascular Care. Medicina 2025, 61, 1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhu, T.; Zhou, T.; Wu, B.; Tan, W.; Ma, K.; Yao, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, S.; Qin, F.; et al. Hyper-DREAM, a Multimodal Digital Transformation Hypertension Management Platform Integrating Large Language Model and Digital Phenotyping: Multicenter Development and Initial Validation Study. J. Med. Syst. 2025, 49, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sertkaya, A.; Beleche, T.; Jessup, A.; Sommers, B.D. Costs of Drug Development and Research and Development Intensity in the US, 2000-2018. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2415445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoens, S.; Huys, I. R&D Costs of New Medicines: A Landscape Analysis. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 760762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayer, V.W.; Nourhussein, I.; Kasle, A.; Hansen, R.N.; Navas, A.; Sullivan, S.D. Comprehensive Access to Semaglutide: Clinical and Economic Implications for Medicare. Value Health 2025, 28, 1488–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, M.T.; Ritchie, N.D.; Norton, B.; Gallucci, A. Opportunities and obstacles associated with the Medicare Diabetes Prevention Program. Am. J. Manag. Care 2025, 31, 578–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sardar, P.; Lee, A. Venture Capital’s Role in Driving Innovation in Cardiovascular Digital Health. JACC Adv. 2024, 3, 100921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, R.; Hartmann, S.; Teepe, G.W.; Lohse, K.M.; Alattas, A.; Tudor Car, L.; Müller-Riemenschneider, F.; von Wangenheim, F.; Mair, J.L.; Kowatsch, T. Digital Behavior Change Interventions for the Prevention and Management of Type 2 Diabetes: Systematic Market Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e33348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safavi, K.C.; Cohen, A.B.; Ting, D.Y.; Chaguturu, S.; Rowe, J.S. Health systems as venture capital investors in digital health: 2011–2019. npj Digit. Med. 2020, 3, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalani, H.S.; Kesselheim, A.S.; Rome, B.N. Potential Medicare Part D savings on generic drugs from the Mark Cuban cost Plus drug Company. Ann. Intern. Med. 2022, 175, 1053–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortese, B.D.; Dusetzina, S.B.; Luckenbaugh, A.N.; Al Hussein Al Awamlh, B.; Stimson, C.; Barocas, D.A.; Penson, D.F.; Chang, S.S.; Talwar, R. Projected savings for generic oncology drugs purchased via Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company versus in Medicare. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 4664–4668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unruh, L.; Rice, T. Private equity expansion and impacts in united states healthcare. Health Policy 2025, 155, 105266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonagh, M.S.; Selph, S.; Ozpinar, A.; Foley, C. Systematic Review of the Benefits and Risks of Metformin in Treating Obesity in Children Aged 18 Years and Younger. JAMA Pediatr. 2014, 168, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khokhar, A.; Umpaichitra, V.; Chin, V.L.; Perez-Colon, S. Metformin Use in Children and Adolescents with Prediabetes. Pediatr. Clin. 2017, 64, 1341–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouvari, M.; Karipidou, M.; Tsiampalis, T.; Mamalaki, E.; Poulimeneas, D.; Bathrellou, E.; Panagiotakos, D.; Yannakoulia, M. Digital Health Interventions for Weight Management in Children and Adolescents: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e30675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannon, M.J.; Masalovich, S.; Ng, B.P.; Soler, R.E.; Jabrah, R.; Ely, E.K.; Smith, B.D. Retention Among Participants in the National Diabetes Prevention Program Lifestyle Change Program, 2012–2017. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 2042–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerowitz-Katz, G.; Ravi, S.; Arnolda, L.; Feng, X.; Maberly, G.; Astell-Burt, T. Rates of Attrition and Dropout in App-Based Interventions for Chronic Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e20283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, M.M.; Chauhan, R.; Davies, M.J.; Brough, C.; Northern, A.; Stribling, B.; Schreder, S.; Khunti, K.; Hadjiconstantinou, M. User Retention and Engagement in the Digital-Based Diabetes Education and Self-Management for Ongoing and Newly Diagnosed (myDESMOND) Program: Descriptive Longitudinal Study. JMIR Diabetes 2023, 8, e44943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, D.V.; Chen, J.; Viswanadham, R.V.N.; Lawrence, K.; Mann, D. Leveraging Machine Learning to Develop Digital Engagement Phenotypes of Users in a Digital Diabetes Prevention Program: Evaluation Study. JMIR AI 2024, 3, e47122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, T.; Lin, Q.; Yu, B.; Hu, J. A systematic review of strategies in digital technologies for motivating adherence to chronic illness self-care. npj Health Syst. 2025, 2, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughnane, C.; Laiti, J.; O’Donovan, R.; Dunne, P.J. Systematic review exploring human, AI, and hybrid health coaching in digital health interventions: Trends, engagement, and lifestyle outcomes. Front. Digit. Health 2025, 7, 1536416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonanni, L.J.; Wittkopp, S.; Long, C.; Aleman, J.O.; Newman, J.D. A review of air pollution as a driver of cardiovascular disease risk across the diabetes spectrum. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1321323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Qin, L.; Gu, R.; Feng, J.; Xu, L.; Meng, X.; Chen, J.; Chen, R.; et al. Association of residential air pollution and green space with all-cause and cause-specific mortality in individuals with diabetes: An 11-year prospective cohort study. eBioMedicine 2024, 108, 105376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasin, N.; Amnuaylojaroen, T.; Saokaew, S.; Sittichai, N.; Tabkhan, N.; Dilokthornsakul, P. Outdoor air pollution exposure and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic umbrella review and meta-analysis. Environ. Res. 2025, 269, 120885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndlovu, N.; Nkeh-Chungag, B.N. Impact of Indoor Air Pollutants on the Cardiovascular Health Outcomes of Older Adults: Systematic Review. Clin. Interv. Aging 2024, 19, 1629–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabaei, S.; Rashki Ghalenoo, S.; Panahandeh, M.; Bagheri, G.; Tabaee, S.S. The relationship between noise pollution and cardiovascular diseases: An umbrella review on meta-analyses. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2025, 25, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münzel, T.; Sørensen, M.; Daiber, A. Transportation noise pollution and cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021, 18, 619–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutson, K.L.; Dixon, D.D.; Grandner, M.A.; Jackson, C.L.; Kline, C.E.; Maher, L.; Makarem, N.; Martino, T.A.; St-Onge, M.-P.; Johnson, D.A.; et al. Role of Circadian Health in Cardiometabolic Health and Disease Risk: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2025, 152, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huntsman, D.D.; Bulaj, G. Home Environment as a Therapeutic Target for Prevention and Treatment of Chronic Diseases: Delivering Restorative Living Spaces, Patient Education and Self-Care by Bridging Biophilic Design, E-Commerce and Digital Health Technologies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulaj, G.; Forero, M.; Huntsman, D.D. Biophilic design, neuroarchitecture and therapeutic home environments: Harnessing medicinal properties of intentionally-designed spaces to enhance digital health outcomes. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1610259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fruh, S.; Williams, S.; Hayes, K.; Hauff, C.; Hudson, G.M.; Sittig, S.; Graves, R.J.; Hall, H.; Barinas, J. A practical approach to obesity prevention: Healthy home habits. J. Am. Assoc. Nurse Pract. 2021, 33, 1055–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrona-Cardoza, P.; Labonté, K.; Cisneros-Franco, J.M.; Nielsen, D.E. The Effects of Food Advertisements on Food Intake and Neural Activity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Recent Experimental Studies. Adv. Nutr. 2023, 14, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, A.; Kenney, E.L.; Dai, J.; Soto, M.J.; Bleich, S.N. The Marketing of Ultraprocessed Foods in a National Sample of U.S. Supermarket Circulars: A Pilot Study. AJPM Focus 2022, 1, 100009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Properties | Metformin | GLP1RA-Based Drugs |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of action | Pleiotropic: suppression of hepatic gluconeogenesis through activation of the AMPK pathway; enhancing insulin secretion; increasing GLP-1 release; reducing the DPP4 activity; anti-inflammatory [59,60,61,62]. | Direct activation of GLP-1 receptors resulting in the increased insulin release, or a dual activation of GLP1/GIP receptors leading to decreased hunger and increased satiety; anti-inflammatory [63,64,65]. |

| Prevention of diabetes | Lowers progression from prediabetes to T2DM by 17–31% compared to placebo. Metformin and lifestyle interventions reduce T2DM incidence by an additional 17% compared to lifestyle alone [66,67,68,69]. | Lowers progression from prediabetes to T2DM by ~30–60% [70,71,72]. |

| Prevention of MACE/CVDs | In comparison to placebo/no therapy, metformin decreases the risk of cardiovascular events and MACE [56,73,74,75,76]. | In comparison to placebo/no therapy, GLP1RAs can reduce MACE by ~12–14% compared to placebo [42,77,78,79,80]. |

| Weight loss | Modest effect on weight loss. In patients with T2DM, up to a 5% total body weight loss can be observed [55]. In patients without T2DM, compared to placebo, metformin can reduce BMI by 2.63% on average. | Reducing total body weight by ~5–15% depending on the medication itself, with liraglutide 3.0 mg leading to 5–8% body weight reduction and semaglutide 2.4 mg leading to 5 to over 15% body weight reduction [81,82]. |

| Safety concerns | Lactic acidosis (very rare); vitamin B12 deficiency [83,84,85]. | GI adverse events (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation) [86,87]. |

| Monthly costs | USD 5.55 a, or 6.09 b | USD 500 c |

| Brand/ Supplier | Indication | Content | Website Listing Clinical Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| WellDoc, Bluestar | Diabetes (type 1 and 2), prediabetes, hypertension, heart failure, obesity and weight management | Real-time digital coaching; integration with CGMs; mental health tools; nutrition and exercise guides; tracking blood pressure, cholesterol, physical activity, calorie intake, and weight | www.welldoc.com (accessed 3 December 2025) |

| Dario Health | Diabetes, prediabetes, hypertension, weight management | Personalized and motivational coaching; virtual care; blood glucose and blood pressure monitoring | www.dariohealth.com (accessed 3 December 2025) |

| Omada Health | Prediabetes, diabetes, hypertension, weight management | Virtual care; medication management; CGM; remote monitoring; behavior change; health coaching and education | www.omadahealth.com (accessed 3 December 2025) |

| Dexcom G7, Stelo | Prediabetes, diabetes | CGM; detecting and reporting blood glucose spikes; logging meals, sleep, and physical activities; personalized insights; health education | www.dexcom.com www.stelo.com (accessed 3 December 2025) |

| Hello Heart | Hypertension | Tracking blood pressure, cholesterol, and medications; personalized health coaching and education | www.helloheart.com (accessed 3 December 2025) |

| AliveCor | Cardiovascular conditions | EKG and blood pressure monitoring; medication management | www.alivecor.com (accessed 3 December 2025) |

| Heart and Stroke Helper app | Stroke survivors | Self-management; tracking lifestyle habits; medication management; health education | Not available |

| Disease | At Risk | Pre-Chronic Disease | Diagnosed Chronic Disease |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus |

|

|

|

| Coronary Artery Disease |

| Diagnostic Tests:

| |

| Hypertension |

| SBP d = 120–129 mmHg AND DBP e < 80 mmHg | SBP d > 130 mmHg OR DBP e > 80 mmHg |

| Heart Failure | Stage A: At Risk for heart failure | Stage B: Pre-Heart Failure | Stage C: Symptomatic Heart Failure Stage D: Advanced Heart Failure |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Farley, B.; Radetich, E.; DAlessandro, J.; Bulaj, G. Metformin-Enhanced Digital Therapeutics for the Affordable Primary Prevention of Diabetes and Cardiovascular Diseases: Advancing Low-Cost Solutions for Lifestyle-Related Chronic Disorders. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3220. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243220

Farley B, Radetich E, DAlessandro J, Bulaj G. Metformin-Enhanced Digital Therapeutics for the Affordable Primary Prevention of Diabetes and Cardiovascular Diseases: Advancing Low-Cost Solutions for Lifestyle-Related Chronic Disorders. Healthcare. 2025; 13(24):3220. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243220

Chicago/Turabian StyleFarley, Brian, Emi Radetich, Joseph DAlessandro, and Grzegorz Bulaj. 2025. "Metformin-Enhanced Digital Therapeutics for the Affordable Primary Prevention of Diabetes and Cardiovascular Diseases: Advancing Low-Cost Solutions for Lifestyle-Related Chronic Disorders" Healthcare 13, no. 24: 3220. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243220

APA StyleFarley, B., Radetich, E., DAlessandro, J., & Bulaj, G. (2025). Metformin-Enhanced Digital Therapeutics for the Affordable Primary Prevention of Diabetes and Cardiovascular Diseases: Advancing Low-Cost Solutions for Lifestyle-Related Chronic Disorders. Healthcare, 13(24), 3220. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243220