Effects of Adapted Physical Activity Programs on Body Composition and Sports Performance in a Patient with Parkinson’s Disease: A Case Report

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participant and Program Overview

2.2. Intervention

2.3. Anthropometric and Performance Assessments

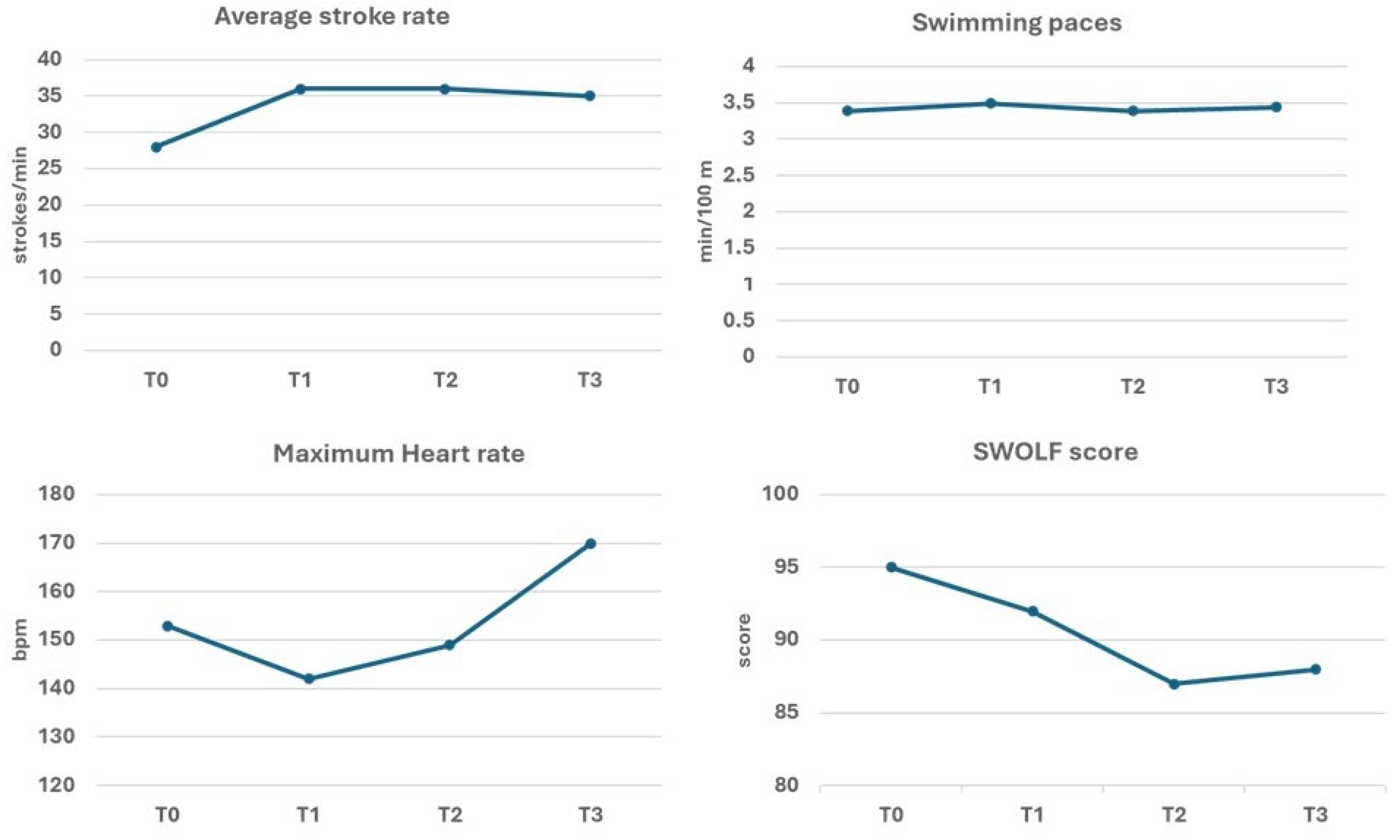

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PD | Parkinson disease |

| APA | adapted physical activity |

| WC | waist circumference |

| MUAC | mid-upper-arm circumference |

| WHtR | waist-to-height ratio |

| AFI | arm fat index |

| FM | fat mass |

| FFM | fat-free mass |

| FMI | Fat Mass Index |

| FFMI | Fat-Free Mass Index |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| VC | Vital capacity |

| FVC | forced vital capacity |

| FEV1 | forced expiratory volume in one second |

| DSST | Digit Symbol Substitution Test |

| SWOLF | swimming golf |

| MCID | minimal clinically important difference |

References

- Kouli, A.; Torsney, K.M.; Kuan, W.L. Parkinson’s Disease: Etiology, Neuropathology, and Pathogenesis. In Parkinson’s Disease: Pathogenesis and Clinical Aspects; Stoker, T.B., Greenland, J.C., Eds.; Codon Publications: Brisbane, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Petzinger, G.M.; Fisher, B.E.; McEwen, S.; Beeler, J.A.; Walsh, J.P.; Jakowec, M.W. Exercise-enhanced neuroplasticity targeting motor and cognitive circuitry in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2013, 12, 716–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson’s Foundation & American College of Sports Medicine. New Exercise Recommendations for the Parkinson’s Community and Exercise Professional. 2020. Available online: https://www.parkinson.org/blog/awareness/exercise-recommendations (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Zhou, X.; Zhao, P.; Guo, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, R. Effectiveness of aerobic and resistance training on the motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 935176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloem, B.R.; Henderson, E.J.; Dorsey, E.R.; Okun, M.S.; Okubadejo, N.; Chan, P.; Andrejack, J.; Darweesh, S.K.L.; Munneke, M. Integrated and patient-centred management of Parkinson’s disease: A network model for reshaping chronic neurological care. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirtošek, Z. Breaking barriers in Parkinson’s care: The multidisciplinary team approach. J. Neural. Transm. 2024, 131, 1349–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamotte, G.; Rafferty, M.R.; Prodoehl, J.; Kohrt, W.M.; Comella, C.L.; Simuni, T.; Corcos, D.M. Effects of Endurance Exercise Training on The Motor and Non-Motor Features of Parkinson’s Disease: A Review. J. Park. Dis. 2015, 5, 993. [Google Scholar]

- Rivadeneyra, J.; Verhagen, O.; Bartulos, M.; Mariscal-Pérez, N.; Collazo, C.; Garcia-Bustillo, A.; Calvo, S.; Cubo, E. The Impact of Dietary Intake and Physical Activity on Body Composition in Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 2021, 8, 896–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ongun, N. Does nutritional status affect Parkinson’s Disease features and quality of life? PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picillo, M.; Nicoletti, A.; Fetoni, V.; Garavaglia, B.; Barone, P.; Pellecchia, M.T. The relevance of gender in Parkinson’s disease: A review. J. Neurol. 2017, 264, 1583–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, I.N.; Cronin-Golomb, A. Gender differences in Parkinson’s disease: Clinical characteristics and cognition. Mov. Disord. 2022, 37, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Yuan, H.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Wen, S. Effects of aquatic exercise on the improvement of lower-extremity motor function and quality of life in patients with Parkinson’s disease: A meta-analysis. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1066718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isidoro-Cabañas, E.; Soto-Rodríguez, F.J.; Morales-Rodríguez, F.M.; Pérez-Mármol, J.M. Benefits of Adaptive Sport on Physical and Mental Quality of Life in People with Physical Disabilities: A Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cugusi, L.; Manca, A.; Bergamin, M.; Di Blasio, A.; Monticone, M.; Deriu, F.; Mercuro, G. Aquatic exercise improves motor impairments in people with Parkinson’s disease, with similar or greater benefits than land-based exercise: A systematic review. J. Physiother. 2019, 65, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagnier, J.J.; Kienle, G.; Altman, D.G.; Moher, D.; Sox, H.; Riley, D.; CARE Group. The CARE guidelines: Consensus-based clinical case reporting guideline development. BMJ Case Rep. 2013, 2013, bcr2013201554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohman, T.G.; Roche, A.F.; Martorell, R. Anthropometric Standardization Reference Manual; Human Kinetics Books: Champaign, IL, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Gualdi-Russo, E.G. Metodi Antropometrici: Generalità e principali caratteri antropometrici. In Manuale di Antropologia. Evoluzione e Biodiversità Umana; Sineo, L., Cecchi, J.M., Eds.; UTET: Torino, Italy, 2022; pp. 55–75. [Google Scholar]

- Frisancho, A.R. Anthropometric Standards for the Assessment of Growth and Nutritional Status; The University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner, J.S.; Lourie, J.A. Practical Human Biology; Academic Press: London, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic; Report of a WHO Consultation; WHO Technical Report Series no. 894; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ashwell, M. Waist to height ratio and the Ashwell® shape chart could predict the health risks of obesity in adults and children in all ethnic groups. Nutr. Food Sci. 2005, 35, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durnin, J.V.; Womersley, J. Body fat assessed from total body density and its estimation from skinfold thickness: Measurements on 481 men and women aged from 16 to 72 years. Br. J. Nutr. 1974, 32, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siri, W.E. Body composition from fluid spaces and density: Analysis of methods. In Techniques for Measuring Body Composition; Brozek, J., Henschel, A., Eds.; National Academy of Sciences: Washington, DC, USA, 1961; pp. 223–244. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, K.H. The Aerobics Program for Total Well-Being; Bantam Books: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Schutz, Y.; Kyle, U.U.; Pichard, C. Fat-free mass index and fat mass index percentiles in Caucasians aged 18-98 y. Int. J. Obes. 2002, 26, 953–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withers, R.T.; Bourdon, P.C.; Crockett, A. Spirometric standards for healthy male lifetime nonsmokers. Hum. Biol. 1989, 61, 327–342. [Google Scholar]

- Nadeau, A.; Lungu, O.; Duchesne, C.; Robillard, M.È.; Bore, A.; Bobeuf, F.; Plamondon, R.; Lafontaine, A.L.; Gheysen, F.; Bherer, L.; et al. A 12-Week Cycling Training Regimen Improves Gait and Executive Functions Concomitantly in People with Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2017, 10, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Smith, B.E.; Shigo, L.; Shaikh, A.G.; Loparo, K.A.; Ridgel, A.L. Assessing Changes in Motor Function and Mobility in Individuals with Parkinson’s Disease After 12 Sessions of Patient-Specific Adaptive Dynamic Cycling. Sensors 2024, 24, 7364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moratelli, J.A.; Delabary, M.D.S.; Curi, V.S.; Passos-Monteiro, E.; Swarowsky, A.; Haas, A.N.; Guimarães, A.C.A. An Exploratory Study on the Effect of 2 Brazilian Dance Protocols on Motor Aspects and Quality of Life of Individuals with Parkinson’s Disease. J. Danc. Med. Sci. 2023, 27, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szefler-Derela, J.; Arkuszewski, M.; Knapik, A.; Wasiuk-Zowada, D.; Gorzkowska, A.; Krzystanek, E. Effectiveness of 6-Week Nordic Walking Training on Functional Performance, Gait Quality, and Quality of Life in Parkinson’s Disease. Medicina 2020, 56, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Waist Circumference and Waist-Hip Ratio: Report of a WHO Expert Consultation; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, P.L.; Cheng, S.J.; Yang, Y.R.; Wang, R.Y. Effects of Dual Task Training on Dual Task Gait Performance and Cognitive Function in Individuals with Parkinson Disease: A Meta-analysis and Meta-regression. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2023, 104, 950–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.H.; Wang, R.Y.; Liu, Y.T.; Cheng, S.J.; Liu, H.H.; Yang, Y.R. Improving Executive Function and Dual-Task Cost in Parkinson Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Neurol. Phys. Ther. 2024, 48, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, F.; Calvani, R.; Martone, A.M.; Salini, S.; Zazzara, M.B.; Candeloro, M.; Coelho-Junior, H.J.; Tosato, M.; Picca, A.; Marzetti, E. Normative values of muscle strength across ages in a ‘real world’ population: Results from the longevity check-up 7+ project. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2020, 11, 1562–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaeger, J. Digit Symbol Substitution Test: The Case for Sensitivity Over Specificity in Neuropsychological Testing. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2018, 38, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsatali, M.; Poptsi, E.; Moraitou, D.; Agogiatou, C.; Bakoglidou, E.; Gialaouzidis, M.; Papasozomenou, C.; Soumpourou, A.; Tsolaki, M. Discriminant Validity of the WAIS-R Digit Symbol Substitution Test in Subjective Cognitive Decline, Mild Cognitive Impairment (Amnestic Subtype) and Alzheimer’s Disease Dementia (ADD) in Greece. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villafañe, J.H.; Valdes, K.; Buraschi, R.; Martinelli, M.; Bissolotti, L.; Negrini, S. Reliability of the Handgrip Strength Test in Elderly Subjects With Parkinson Disease. Hand 2016, 11, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawaya, Y.; Ishizaka, M.; Hirose, T.; Shiba, T.; Onoda, K.; Kubo, A.; Maruyama, H.; Urano, T. Minimal detectable change in handgrip strength and usual and maximum gait speed scores in community-dwelling Japanese older adults requiring long-term care/support. Geriatr. Nurs. 2021, 42, 1184–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, N.A.; Ford, M.P.; Standaert, D.G.; Watts, R.L.; Bickel, C.S.; Moellering, D.R.; Tuggle, S.C.; Williams, J.Y.; Lieb, L.; Windham, S.T.; et al. Novel, high-intensity exercise prescription improves muscle mass, mitochondrial function, and physical capacity in individuals with Parkinson’s disease. J. Appl. Physiol. 2014, 116, 582–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubert, C.; Kong, G.; Renoir, T.; Hannan, A.J. Exercise, diet and stress as modulators of gut microbiota: Implications for neurodegenerative diseases. Neurobiol. Dis. 2020, 134, 104621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Berg, I.; Schootemeijer, S.; Overbeek, K.; Bloem, B.R.; de Vries, N.M. Dietary Interventions in Parkinson’s Disease. J. Park. Dis. 2024, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissolotti, L.; Rota, M.; Calza, S.; Romero-Morales, C.; Alonso-Pérez, J.L.; López-Bueno, R.; Villafañe, J.H. Gender-Specific Differences in Spinal Alignment and Muscle Power in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongmala, C.; Stonsaovapak, C.; van Emde Boas, M.; Bhanderi, H.; Luker, A.; Michalakis, F.; Kanel, P.; Albin, R.L.; Haus, J.M.; Bohnen, N.I. Body Composition, Falls, and Freezing of Gait in Parkinson’s Disease: Gender-Specific Effects. J. Frailty Aging 2024, 13, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Timepoint | Test | Adapted Physical Activity |

|---|---|---|

| T0 − 4 years | PD Diagnosis | |

| T0 − 18 months | Start gym-based APA + Nordic walking | |

| T0 − 1 week | First anthropometric measurement | |

| T0 | Baseline: swimming skills assessment, and establishment of individualized training goals | |

| T0 + 1 week | Start of Adapted swimming training | |

| T1 (8 weeks) | Second motor test (T1) | |

| T2 (16 weeks) | Third motor test (T2) | |

| T3 − 1 week | Second anthropometric measurement | |

| T3 (6 September 2022) | Final motor test (T3) | Participation in the open water Swim 4 Parkinson |

| Modality | Frequency | Intensity (HR) | Time | Adherence (% Completed) | Task Description/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gym-based APA | 1×/week | HR 60–70% max | 60 min | 95 | Mobility, strengthening, and low-intensity aerobic exercises |

| Nordic Walking | 1×/week | HR 65–75% max | 50–60 min | 100 | Outdoor walking with poles; progressive distance based on tolerance |

| Swimming (pool) | 2×/week | HR 60–75% max | 40–50 min | 90 | Technique and endurance training; gradual increase in distance |

| Swimming (open water) | 1×/week (last month) | HR 60–70% max | 40–50 min | 100 | Fully supervised. Focus on orientation, safety, and gradual distance progression according to sea conditions and participant tolerance. |

| Variables | Pre-Intervention | Post-Intervention | Δ | %Δ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Somatometric traits | ||||

| Standing height (cm) | 158.5 | - | - | |

| Weight (kg) | 64.2 | 60.7 | −3.5 | −5.5 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.56 | 24.16 | −1.4 | −5.5 |

| WC (cm) | 85.4 | 80.4 | −5.0 | −5.9 |

| WHtR | 0.54 | 0.51 | −0.03 | −5.6 |

| Biceps skinfold (mm) | 4 | 3 | −1 | −25 |

| Triceps skinfold (mm) | 9 | 8 | −1 | −11.1 |

| Subscapular skinfold (mm) | 11 | 8 | −3 | −27.3 |

| Suprailiac skinfold (mm) | 13 | 9 | −4 | −30.8 |

| Sum of skinfolds (mm) | 37 | 28 | −9 | −24.3 |

| %F | 17.1 | 12.7 | −4.4 | −25.7 |

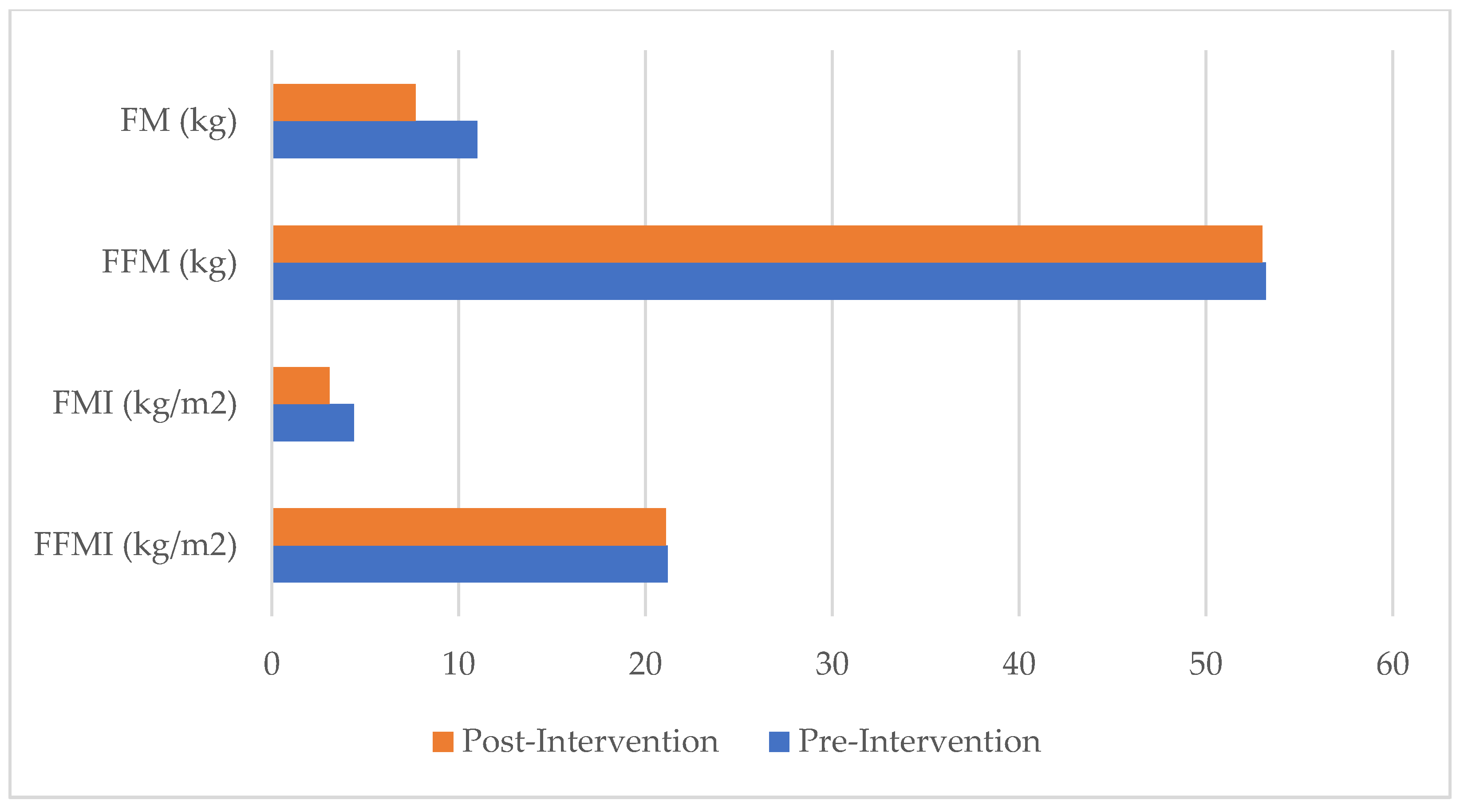

| FM (kg) | 11.0 | 7.7 | −3.3 | −30.0 |

| FFM (kg) | 53.2 | 53.0 | −0.2 | 0.004 |

| FMI (kg/m2) | 4.38 | 3.07 | −1.31 | −29.9 |

| FFMI (kg/m2) | 21.18 | 21.10 | −0.08 | −0.4 |

| MUAC relaxed (cm) | 27.2 | 26.0 | −1.2 | −4.4 |

| MUAC contracted (cm) | 29.9 | 29.9 | 0 | 0 |

| AFI (%) | 19.7 | 18.4 | −1.3 | −6.6 |

| Physiometric traits | ||||

| VC (L) | 3.92 | 4.24 | +0.32 | 8.2 |

| FVC (L) | 4.27 | 4.16 | −0.11 | −2.6 |

| FEV1 (L) | 3.40 | 3.44 | +0.04 | 1.2 |

| Right hand strength (kg) | 47.0 | 48.5 | +1.5 | 3.2 |

| Left hand strength (kg) | 45.0 | 49.5 | +4.5 | 10 |

| DSST (score) | 19 | 23 | +4 | 21.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zaccagni, L.; Rinaldo, N.; Campanale, G.; Pastore, A.; Rametta, F.; Gualdi-Russo, E. Effects of Adapted Physical Activity Programs on Body Composition and Sports Performance in a Patient with Parkinson’s Disease: A Case Report. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3195. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243195

Zaccagni L, Rinaldo N, Campanale G, Pastore A, Rametta F, Gualdi-Russo E. Effects of Adapted Physical Activity Programs on Body Composition and Sports Performance in a Patient with Parkinson’s Disease: A Case Report. Healthcare. 2025; 13(24):3195. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243195

Chicago/Turabian StyleZaccagni, Luciana, Natascia Rinaldo, Gaetano Campanale, Antonio Pastore, Francesca Rametta, and Emanuela Gualdi-Russo. 2025. "Effects of Adapted Physical Activity Programs on Body Composition and Sports Performance in a Patient with Parkinson’s Disease: A Case Report" Healthcare 13, no. 24: 3195. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243195

APA StyleZaccagni, L., Rinaldo, N., Campanale, G., Pastore, A., Rametta, F., & Gualdi-Russo, E. (2025). Effects of Adapted Physical Activity Programs on Body Composition and Sports Performance in a Patient with Parkinson’s Disease: A Case Report. Healthcare, 13(24), 3195. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243195