Assisted Reproduction Therapy in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: Narrative Review and Practical Recommendations

Abstract

1. Introduction

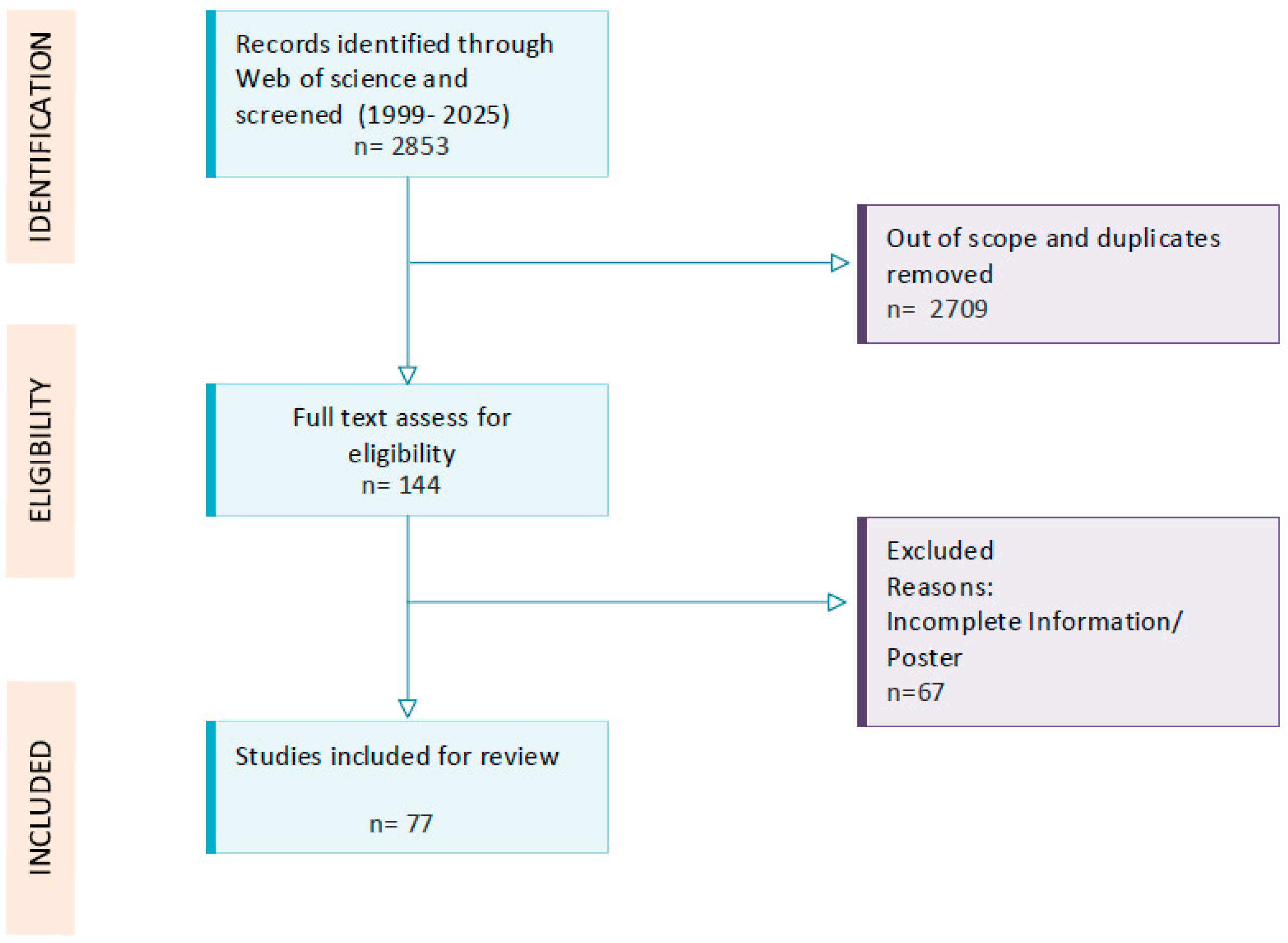

2. Methods

2.1. Etiopathogenesis of Multiple Sclerosis

- Peripheral Activation of the Immune System

- 2.

- Inflammation and Damage in the Central Nervous system; the multiple sclerosis continuum: From Inflammation to Neurodegeneration

2.1.1. Multiple Sclerosis and Reproduction

2.1.2. The Effect of MS on AMH Level

2.1.3. The Influence of Sex Hormones on the Development and Course of MS

2.1.4. Menstrual Cycle

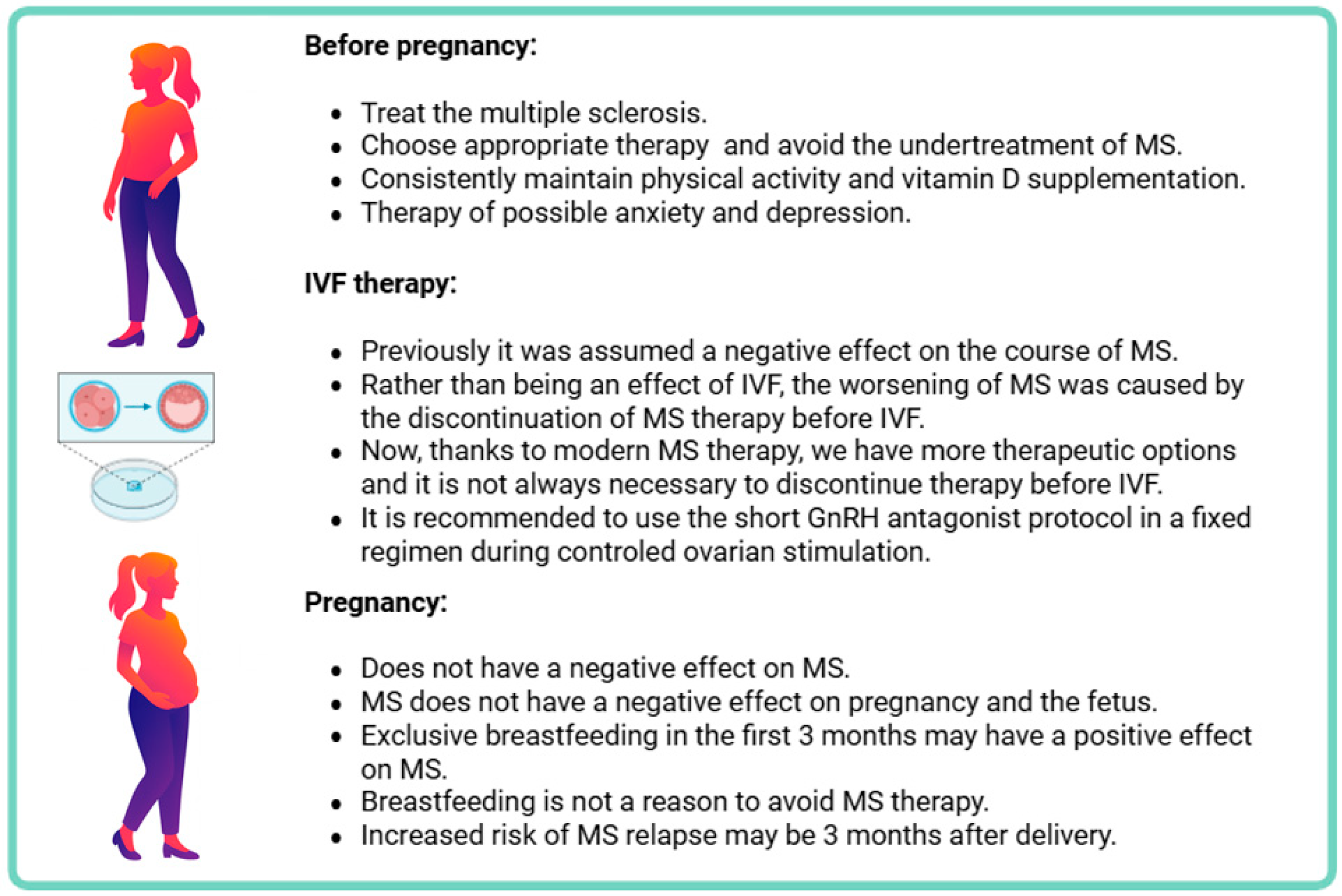

2.1.5. Pregnancy

2.1.6. MS Therapy and Possible Risks of ART

2.1.7. Pregnancy and Treatment of MS

2.2. Assisted Reproduction Methods in Relation to MS

2.2.1. The Impact of ART on the Risk of Developing MS

2.2.2. The Impact of ART on the Course of MS

Older Studies: Increased Risk of Relapses

New Insights: Stabilization Thanks to Modern Therapy

2.2.3. Oocyte Cryopreservation (OC)

2.2.4. Embryo Cryopreservation (EC)

2.3. Recommendations for the Management of Assisted Reproduction in Women with Multiple Sclerosis

- Pre-conception Counseling & Disease Stabilization

- Women with MS should undergo individualized pre-conception counseling involving a multidisciplinary team (neurologist, gynecologist, embryologist, radiologist).

- ART should be planned only when MS is clinically and radiologically stable, ideally under a modern DMT regimen.

- Do not discontinue DMT prematurely; abrupt cessation—especially of fingolimod or natalizumab—significantly increases relapse risk.

- Ovarian Reserve Assessment & Fertility Preservation

- Evaluate ovarian reserve using AMH levels and antral follicle count before initiating ART [68].

- Discuss fertility preservation options (oocyte or embryo cryopreservation) early, particularly in:

- ∘

- young women not yet ready for pregnancy

- ∘

- those requiring DMTs with long washout periods

- ∘

- patients with expected disease progression

- Selection of Ovarian Stimulation Protocol

- Prefer GnRH antagonist protocols or letrozole-based stimulation, which are associated with lower relapse risk than older GnRH agonist protocols.

- Avoid high-estrogen stimulation approaches in unstable MS unless strongly indicated.

- Minimize treatment-induced hormonal fluctuations, which may trigger MS activity.

- Use follitropin alpha/beta or delta for ovarian stimulation.

- Use GnRH agonist for final oocyte maturation in women seeking fertility preservation for medical reasons [75].

- ART Procedure and Monitoring

- Maintain DMT when clinically justified; continued or minimally interrupted therapy reduces relapse risk during ART.

- Monitor Neurological Symptoms Closely During:

- ∘

- ovarian stimulation

- ∘

- postoperative period

- ∘

- and the 3 months following unsuccessful cycles, when relapse risk is highest

- Management After Embryo Transfer and During Pregnancy

- Once pregnant, continue care in an interdisciplinary setting.

- Select pregnancy-compatible DMTs for women at high relapse risk.

- Recognize the postpartum period as a vulnerable phase; plan proactive monitoring and early postpartum management.

- Shared Decision-Making

- Tailor ART and MS therapy decisions to:

- ∘

- disease activity

- ∘

- age and ovarian reserve

- ∘

- reproductive goals

- ∘

- and prior ART outcomes

- Engage the patient in shared decision-making to balance fertility desires with disease control and treatment safety (summarized in Table 2).

2.4. Future Perspectives

2.5. Limitations

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. 1 in 6 People Globally Affected by Infertility. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/04-04-2023-1-in-6-people-globally-affected-by-infertility#:~:text=Around%2017.5%25%20of%20the%20adult,prevalence%20of%20infertility%20between%20regions (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Choudhary, P.; Dogra, P.; Sharma, K. Infertility and lifestyle factors: How habits shape reproductive health. Middle East Fertil. Soc. J. 2025, 30, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennerholm, U.B.; Bergh, C. Perinatal outcome in children born after assisted reproductive technologies. Upsala J. Med. Sci. 2020, 125, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadam, A.R.E.; Moghadam, M.T.; Hemadi, M.; Saki, G. Oocyte quality and aging. JBRA Assist. Reprod. 2022, 26, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2016 Multiple Sclerosis Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of multiple sclerosis 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Arias, J.Á.; Ramos-Campo, D.J.; Romero-Parra, N.; Andreu-Caravaca, L.; Martínez-Rodríguez, A.; Esteban-García, P.; López-Liria, R.; Molina-Torres, G.; Ventura-Miranda, M.I.; Martos-Bonilla, A.; et al. Response to physical activity of females with multiple sclerosis throughout the menstrual cycle: A protocol for a randomised crossover trial (EMMA Project). BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2023, 9, e001797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, P.K. Management of women with multiple sclerosis through pregnancy and after childbirth. Ther. Adv. Neurol. Disord. 2016, 9, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, V.M.; Nelson, L.M.; Chakravarty, E.F. Obstetric outcomes in women with multiple sclerosis and epilepsy. Neurology 2009, 73, 1831–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellwig, K.; Correale, J. Artificial reproductive techniques in multiple sclerosis. Clin. Immunol. 2013, 149, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondschein, C.F.; Monda, C. The EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in a Research Context. In Fundamentals of Clinical Data Science; Kubben, P., Dumontier, M., Dekker, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, S.L.; Cree, B.A.C. Treatment of Multiple Sclerosis: A Review. Am. J. Med. 2020, 133, 1380–1390.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arneth, B. Genes, gene loci, and their impacts on the immune system in the development of multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarghami, A.; Li, Y.; Claflin, S.B.; van der Mei, I.; Taylor, B.V. Role of environmental factors in multiple sclerosis. Expert. Rev. Neurother. 2021, 21, 1389–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portaccio, E.; Magyari, M.; Havrdova, E.K.; Ruet, A.; Brochet, B.; Scalfari, A.; Di Filippo, M.; Tur, C.; Montalban, X.; Amato, M.P. Multiple sclerosis: Emerging epidemiological trends and redefining the clinical course. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2024, 44, 100977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasooriya, N.N.; Elliott, T.M.; Neale, R.E.; Vasquez, P.; Comans, T.; Gordon, L.G. The association between vitamin D deficiency and multiple sclerosis: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2024, 90, 105804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, T.W.; Perez-Gomez, A.; Lawley, K.; Young, C.R.; Welsh, C.J.; Brinkmeyer-Langford, C.L. Comparative analysis of genetic risk for viral-induced axonal loss in genetically diverse mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianfrancesco, M.A.; Stridh, P.; Rhead, B.; Shao, X.; Xu, E.; Graves, J.S.; Chitnis, T.; Waldman, A.; Loetze, T.; Schreiner, T.; et al. Evidence for a causal relationship between low vitamin D, high BMI, and pediatric-onset MS. Neurology 2017, 88, 1623–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Langelaar, J.; Rijvers, L.; Smolders, J.; van Luijn, M.M. B and T Cells driving multiple sclerosis: Identity, mechanisms and potential triggers. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanz, T.V.; Brewer, R.C.; Ho, P.P.; Moon, J.-S.; Jude, K.M.; Fernandez, D.; Fernandes, R.A.; Gomez, A.M.; Nadj, G.-S.; Bartley, C.M.; et al. Clonally Expanded B Cells in Multiple Sclerosis Bind EBV EBNA1 and GlialCAM. Nature 2022, 603, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias de Sousa, M.A.; Desidério, C.S.; da Silva Catarino, J.; Trevisan, R.O.; Alves da Silva, D.A.; Rocha, V.F.R.; Bovi, W.G.; Timoteo, R.P.; Bonatti, R.C.F.; da Silva, A.E.; et al. Role of cytokines, chemokines and IFN-γ+ IL-17+ double-positive CD4+ T cells in patients with multiple sclerosis. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2062. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, J.; Bar-Or, A. Emerging therapies to target CNS pathophysiology in multiple sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2022, 18, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lassmann, H. Pathology and disease mechanisms in different stages of multiple sclerosis. J. Neurol. Sci. 2013, 333, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollmer, T.L.; Nair, K.V.; Williams, I.M.; Alvarez, E. Multiple Sclerosis Phenotypes as a Continuum: The Role of Neurologic Reserve. Neurol. Clin. Pract. 2021, 11, 342–351. [Google Scholar]

- Lublin, F.D.; Reingold, S.C.; Cohen, J.A.; Cutter, G.R.; Sørensen, P.S.; Thompson, A.J.; Wolinsky, J.S.; Balcer, L.J.; Banwell, B.; Barkhof, F.; et al. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: The 2013 revisions. Neurology 2014, 83, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente Escudero, J.L. Meta analysis of the efficacy of web based psychological treatments on anxiety, depression, fatigue, and quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis. J. Technol. Behav. Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, M.S.; Engler, J.B.; Friese, M.A. The neuropathobiology of multiple sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2024, 25, 493–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, L.; Landi, D.; Di Girolamo, R.; Anserini, P.; Centonze, D.; Marfia, G.A.; Alviggi, C.; Interdisciplinary Group for Fertility in Multiple Sclerosis (IGFMS). Optimizing the “Time to pregnancy” in women with multiple sclerosis: The OPTIMUS Delphi survey. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1255496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainguy, M.; Casey, R.; Vukusic, S.; Lebrun-Frenay, C.; Berger, E.; Kerbrat, A.; Al Khedr, A.; Bourre, B.; Ciron, J.; Clavelou, P.; et al. Assessing the risk of relapse after in vitro fertilization in women with multiple sclerosis. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 2025, 12, e200371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaki, M.A.; Ramzy, G.; Ali, S.; Sharaf, S.A.; Hegazy, M.I.; Mostafa, E.; Fawzy, I.; El-Ghoneimy, L. Multiple sclerosis and fecundity: A study of anti-mullerian hormone level in Egyptian patients. Egypt J. Neurol. Psychiatry Neurosurg. 2023, 59, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, T.; Courtillot, C.; Debs, R.; Touraine, P.; Lubetzki, C.; Papeix, C. Fecundity in women with multiple sclerosis: An observational mono-centric study. J. Neurol. 2015, 262, 957–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weil, S.; Vendola, K.; Zhou, J.; Bondy, C.A. Androgen and follicle-stimulating hormone interactions in primate ovarian follicle development. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1999, 84, 2951–2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houtchens, M.K.; Kaplan, T.B. Reproductive Issues in MS. In Seminars in Neurology; Thieme Medical Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 37, pp. 632–642. [Google Scholar]

- Lavorgna, L.; Esposito, S.; Lanzillo, R.; Sparaco, M.; Ippolito, D.; Cocco, E.; Fenu, G.; Borriello, G.; De Mercanti, S.; Frau, J.; et al. Factors interfering with parenthood decision-making in an Italian sample of people with multiple sclerosis: An exploratory online survey. J. Neurol. 2019, 266, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawamara, K.; Kelsey, T.; Hiraike, O. Editorial: Ovarian Ageing: Pathophysiology and recent development of maintaining ovarian reserve. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 591764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, M.P.; Portaccio, E. Fertility, pregnancy and childbirth in patients with multiple sclerosis: Impact of disease-modifying drugs. CNS Drugs 2015, 29, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocco, E.; Sardu, C.; Gallo, P.; Capra, R.; Amato, M.; Trojano, M.; Uccelli, A.; Marrosu, M.; The FEMIMS Group. Frequency and risk factors of mitoxantrone-induced amenorrhea in multiple sclerosis: The FEMIMS study. Mult. Scler. 2008, 14, 1225–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Themmen, A.P. Anti-Müllerian hormone: Its role in follicular growth initiation and survival and as an ovarian reserve marker. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2005, 34, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visser, J.A.; Themmen, A.P. Anti-Müllerian hormone and folliculogenesis. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2005, 234, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlinger, A.L.; Visser, J.A.; Themmen, A.P. Regulation of ovarian function: The role of anti-Müllerian hormone. Reproduction 2002, 124, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.-F.; Yan, Y.; Wang, H.-Y.; Chu, M.-Y.; Sun, K.; Feng, Z.-W.; Feng, H. Effect of systemic lupus erythematosus on the ovarian reserve: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Jt. Bone Spine 2024, 91, 105728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrpour, M.; Taherian, F.; Arfa-Fatollahkhani, P.; Moghadasi, A.N.; Mokhtar, S.; Keivani, H. Serum anti-Müllerian hormone levels in multiple sclerosis—A multicentre case-control study. Ces. Slov. Neurol. Neurochir. 2018, 81, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, S.A.A.; Zaki, M.A.; Ramzy, G.M.; Hegazy, M.I.; Sharaf, S.A.E.A. Anti-mullerian hormone levels in female egyptian multiple sclerosis patients. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2023, 80, 105289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, J.S.; Henry, R.G.; Cree, B.A.; Lambert-Messerlian, G.; Greenblatt, R.M.; Waubant, E.; Cedars, M.I.; Zhu, A.; Bacchetti, P.; Hauser, S.L.; et al. Ovarian aging is associated with gray matter volume and disability in women with MS. Neurology 2018, 90, e254–e260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bove, R.; Healy, B.; Secor, E.; Vaughan, T.; Katic, B.; Chitnis, T.; Wicks, P.; De Jager, P. Patients report worse MS symptoms after menopause: Findings from an online cohort. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2015, 4, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bove, R.; Healy, B.C.; Musallam, A.; Glanz, B.I.; De Jager, P.L.; Chitnis, T. Exploration of changes in disability after menopause in a longitudinal multiple sclerosis cohort. Mult. Scler. 2016, 22, 935–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, L.; Di Girolamo, R.; Conforti, A.; Iorio, G.G.; Simeon, V.; Landi, D.; Marfia, G.A.; Lanzillo, R.; Alviggi, C. Ovarian reserve in patients with multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obs. 2023, 163, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thöne, J.; Kollar, S.; Nousome, D.; Ellrichmann, G.; Kleiter, I.; Gold, R.; Hellwig, K. Serum anti-Müllerian hormone levels in reproductive-age women with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. 2015, 21, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda, M.; Ros, C.; Martínez-Lapiscina, E.H.; Solà-Valls, N.; Hervàs, M.; Llufriu, S.; La Puma, D.; Casals, E.; Blanco, Y.; Villoslada, P.; et al. Pituitary-ovary axis and ovarian reserve in fertile women with multiple sclerosis: A pilot study. Mult. Scler. 2015, 22, 564–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bove, R.; Chitnis, T. The role of gender and sex hormones in determining the onset and outcome of multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. 2014, 20, 520–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Li, J.; Huang, S.Y.; Sun, X. Characterization of the subsets of human NKT-like cells and the expression of Th1/Th2 cytokines in patients with unexplained recurrent spontaneous abortion. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2015, 110, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparaco, M.; Bonavita, S. The role of sex hormones in women with multiple sclerosis: From puberty to assisted reproductive techniques. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2021, 60, 100889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montalban, X.; Gold, R.; Thompson, A.J.; Otero-Romero, S.; Amato, M.P.; Chandraratna, D.; Clanet, M.; Comi, G.; Derfuss, T.; Fazekas, F.; et al. ECTRIMS/EAN guideline on the pharmacological treatment of people with multiple sclerosis. Eur. J. Neurol. 2018, 25, 215–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houtchens, M.K. Pregnancy and reproductive health in women with multiple sclerosis: An update. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2024, 37, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confavreux, C.; Hutchinson, M.; Hours, M.M.; Cortinovis-Tourniaire, P.; Moreau, T. Rate of pregnancy-related relapse in multiple sclerosis. Pregnancy in Multiple Sclerosis Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 339, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, D.C.; Hart, S.L.; Julian, L.; Cox, D.; Pelletier, D. Association between stressful life events and exacerbation in multiple sclerosis: A meta-analysis. BMJ 2004, 328, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladwig, A.; Dunkl, V.; Richter, N.; Schroeter, M. Two cases of multiple sclerosis manifesting after in vitro fertilization procedures. J. Neurol. 2016, 263, 603–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaknin-Dembinsky, A.; Bdolah, Y.; Karussis, D.; Rosenthal, G.; Petrou, P.; Fellig, Y.; Abramsky, O.; Lossos, A. Tumefactive demyelination following in vitro fertilization (IVF). J. Neurol. Sci. 2015, 348, 256–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopp, T.I.; Pinborg, A.; Glazer, C.H.; Magyari, M. Assisted reproductive technology treatment and risk of multiple sclerosis—A Danish cohort study. Fertil. Steril. 2023, 119, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellwig, K.; Beste, C.; Brune, N.; Haghikia, A.; Muller, T.; Schimrigk, S.; Gold, R. Increased MS relapse rate during assisted reproduction technique. J. Neurol. 2008, 255, 592–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michel, L.; Foucher, Y.; Vukusic, S.; Confavreux, C.; de Sèze, J.; Brassat, D.; Clanet, M.; Clavelou, P.; Ouallet, J.C.; Brochet, B. Increased risk of multiple sclerosis relapse after in vitro fertilisation. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2012, 83, 796–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bove, R.; Rankin, K.; Lin, C.; Zhao, C.; Correale, J.; Hellwig, K.; Michel, L.; Laplaud, D.A.; Chitnis, T. Effect of assisted reproductive technology on multiple sclerosis relapses: Case series and meta-analysis. Mult. Scler. 2020, 26, 1410–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, M. Maintenance of immunomodulatory treatment during assisted reproductive technology reduces relapse risk in multiple sclerosis. In Proceedings of the AAN Annual Meeting, Boston, MA, USA, 22–27 April 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, E.L.; Bakkensen, J.B.; Anderson, A.; Lancki, N.; Davidson, A.; Perez Giraldo, G.; Jungheim, E.S.; Vanderhoff, A.C.; Ostrem, B.; Mok-Lin, E.; et al. Inflammatory activity after diverse fertility treatments: A multicenter analysis in the modern multiple sclerosis treatment Era. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 2023, 10, e200106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correale, J.; Farez, M.F.; Ysrraelit, M.C. Increase in multiple sclerosis activity after assisted reproduction technology. Ann. Neurol. 2012, 72, 682–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bove, R.; Chitnis, T. Sexual disparities in the incidence and course of MS. Clin. Immunol. 2013, 149, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemmer, B.; Kerschensteiner, M.; Korn, T. Role of the innate and adaptive immune responses in the course of multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2015, 14, 406–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sparaco, M.; Carbone, L.; Landi, D.; Ingrasciotta, Y.; Di Girolamo, R.; Vitturi, G.; Marfia, G.A.; Alviggi, C.; Bonavita, S. Assisted reproductive technology and disease management in infertile women with multiple sclerosis. CNS Drugs 2023, 37, 849–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulga, O.; Hrytsko, M.; Romaniuk, A.; Kotsiuba, O. Assisted reproductive technologies in multiple sclerosis: Literature review. Reprod. Endocrinol. 2024, 72, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkildsen, Ø.; Holmøy, T.; Myhr, K.M. Severe multiple sclerosis reactivation after gonadotropin treatment. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2018, 22, 38–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maunula, A.; Atula, S.; Laakso, S.M.; Tienari, P.J. Frequency and risk factors of rebound after fingolimod discontinuation—A retrospective study. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2024, 81, 105134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, K.; Shinohara, K.; Imai, T.; Yamano, Y.; Hasegawa, Y. Severe multiple sclerosis manifesting upon gnrh agonist therapy for uterine fibroids. Intern. Med. 2020, 59, 3093–3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisková, I.; Mekiňová, L.; Hudeček, R.; Ješeta, M.; Šimová, S. Methods and techniques of fertility preservation in patients with endometriosis. Ces. Gynekol. 2023, 88, 454–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The ESHRE Guideline Group on Female Fertility Preservation; Anderson, R.A.; Amant, F.; Braat, D.; D’Angelo, A.; Chuva de Sousa Lopes, S.M.; Demeestere, I.; Dwek, S.; Frith, L.; Lambertini, M.; et al. ESHRE guideline: Female fertility preservation. Hum. Reprod. Open 2020, 2020, hoaa052. [Google Scholar]

- Ata, B.; Bosch, E.; Broer, S.; Griesinger, G.; Grynberg, M.; Kolibianakis, E.; Kunicki, M.; Marca, A.L.; Lainas, G.; Le Clef, N.; et al. The ESHRE Guideline Group on Ovarian Stimulation, Update 2025. 2025. Available online: https://www.eshre.eu/Guidelines-and-Legal/Guidelines/Ovarian-Stimulation-in-IVF-ICSI (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Jølving, L.R.; Larsen, M.D.; Fedder, J.; Nørgård, B.M. Live birth in women with multiple sclerosis receiving assisted reproduction. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2020, 40, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Year | Study Design | Sample Size/ART Cycles | Reaps Rate (RR) GnRH Agonist | After ART GnRH Antagonist | Notes | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hellwig et al. [60] | 2008 | R, P | 23/78 | Increased | Increased | RR increased independently on the intervals between | Germany |

| Michel et al. [61] | 2012 | R | 32/70 | Increased | Not-increased | RR increased after ART failure | France |

| Correale et al. [65] | 2012 | P | 16/26 | Increased | Non included | ninefold increased in the risk of MRI activity | Argentina |

| Bove et al. [62] | 2020 | C, MA | 12/22 | Not-increased | Not-increased | Small study, higher RR when topped treatment > 3 months before VF than patients which continued in ART | USA |

| Mainguy et al. [29] | 2025 | R | 115/199 | Not-increased | Not-increased | Lower RR after ART taking DMTS | France |

| Graham et al. [64] | 2023 | R | 65/124 | Not-increased | Not-increased | RR increased after 2 or more stimulations | USA |

| Kopp et al. [59] | 2023 | C, MA | 585,716/63,791 | Not-increased | Not-increased | non significant trend toward increased risk of MS with higher number of ART cycles | Denmark |

| Category | Key Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Pre-conception Counseling & Disease Stabilization | Individualized counseling; plan ART only when MS is stable; avoid premature DMT discontinuation. |

| Ovarian Reserve Assessment & Fertility Preservation | Assess AMH and AFC; discuss oocyte/embryo freezing especially in young women or those on long washout DMTs. |

| Selection of Stimulation Protocol | Prefer GnRH antagonist or letrozole-based protocols; avoid high-estrogen stimulation in unstable MS. |

| ART Procedure and Monitoring | Maintain DMT when justified; monitor closely during stimulation, post-op, and 3 months after unsuccessful cycles. |

| Management After Embryo Transfer & Pregnancy | Continue interdisciplinary care; select pregnancy-compatible DMTs; monitor proactively postpartum. |

| Shared Decision-Making | Tailor ART to disease activity, age, ovarian reserve, and patient goals. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mekiňová, L.; Šrotová, I.; Hanáková, P.; Danhofer, P.; Hudeček, R.; Ješeta, M. Assisted Reproduction Therapy in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: Narrative Review and Practical Recommendations. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3155. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233155

Mekiňová L, Šrotová I, Hanáková P, Danhofer P, Hudeček R, Ješeta M. Assisted Reproduction Therapy in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: Narrative Review and Practical Recommendations. Healthcare. 2025; 13(23):3155. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233155

Chicago/Turabian StyleMekiňová, Lenka, Iva Šrotová, Petra Hanáková, Pavlína Danhofer, Robert Hudeček, and Michal Ješeta. 2025. "Assisted Reproduction Therapy in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: Narrative Review and Practical Recommendations" Healthcare 13, no. 23: 3155. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233155

APA StyleMekiňová, L., Šrotová, I., Hanáková, P., Danhofer, P., Hudeček, R., & Ješeta, M. (2025). Assisted Reproduction Therapy in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: Narrative Review and Practical Recommendations. Healthcare, 13(23), 3155. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233155