Knowledge, Attitude, and Intention to Receive the Pertussis Vaccine in Pregnant Women: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

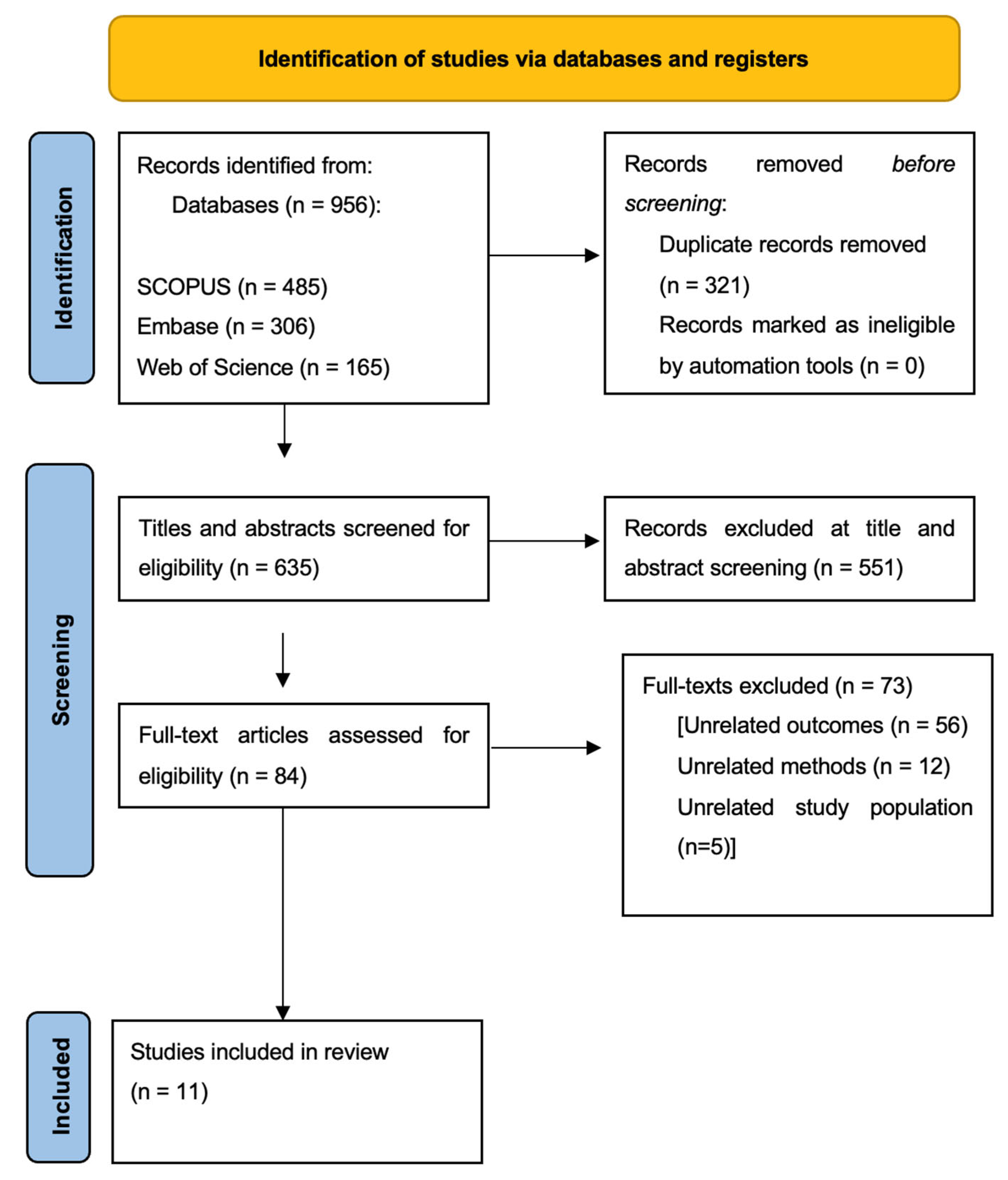

2. Materials and Methods

Search Strategy and Selection of Studies

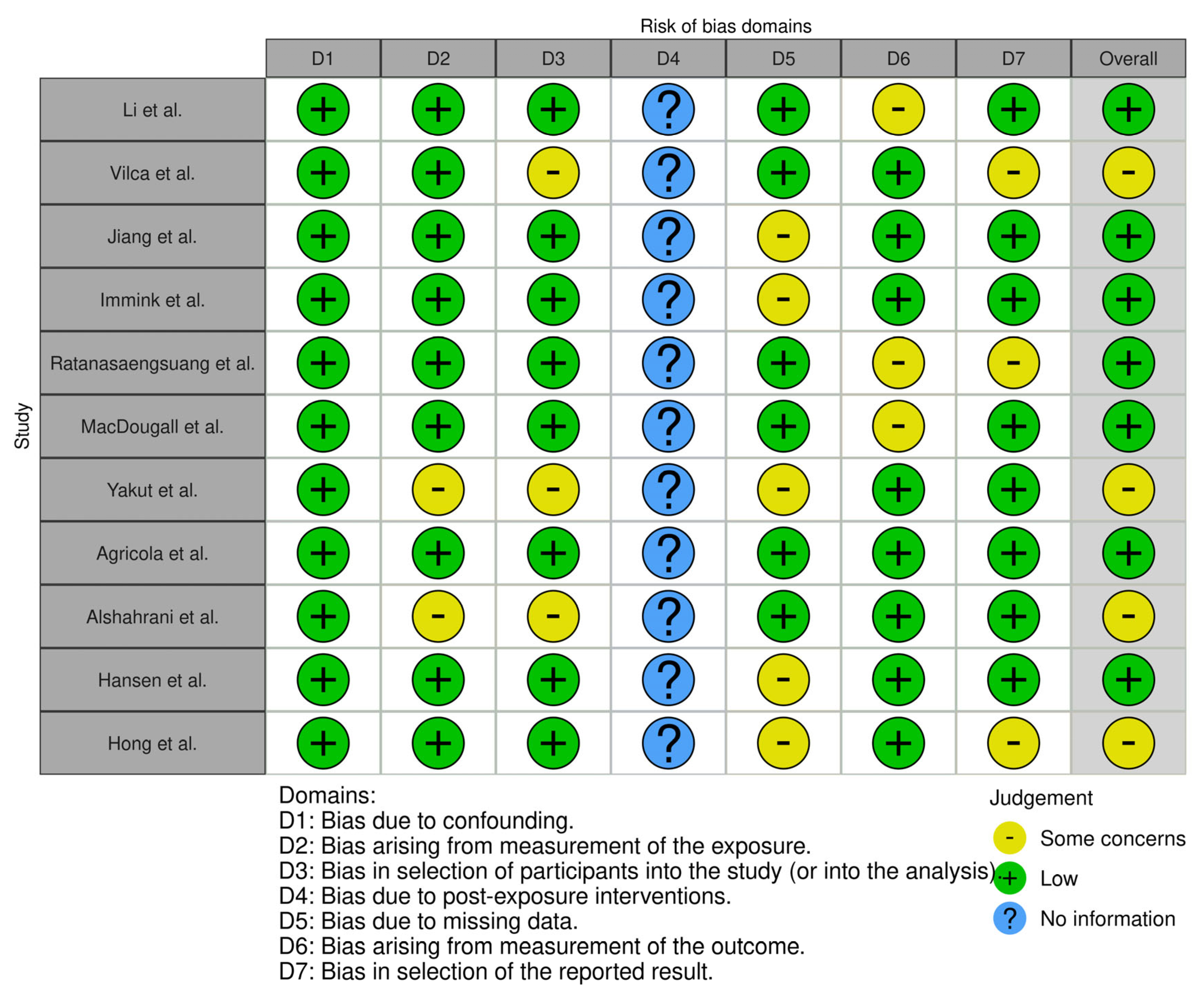

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Decker, M.D.; Edwards, K.M. Pertussis (Whooping Cough). J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 224 (Suppl. 2), S310–S320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- van der Maas, N.A.T.; Sanders, E.A.M.; Versteegh, F.G.A.; Baauw, A.; Westerhof, A.; de Melker, H.E. Pertussis hospitalizations among term and preterm infants: Clinical course and vaccine effectiveness. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- WHO Vaccine-Preventable Diseases: Monitoring System. 2020. Available online: https://apps.who.int/immunization_monitoring/globalsummary/incidences?c=KWT (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Guo, S.; Zhu, Y.; Guo, Q.; Wan, C. Severe pertussis in infants: A scoping review. Ann. Med. 2024, 56, 2352606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Erythromycin-resistant Bordetella pertussis—Yuma County, Arizona, May-October 1994. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 1994, 43, 807–810. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shahcheraghi, F.; Nakhost Lotfi, M.; Nikbin, V.S.; Shooraj, F.; Azizian, R.; Parzadeh, M.; Allahyar Torkaman, M.R.; Zahraei, S.M. The First Macrolide-Resistant Bordetella pertussis Strains Isolated From Iranian Patients. Jundishapur J. Microbiol. 2014, 7, e10880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Heininger, U.; Klich, K.; Stehr, K.; Cherry, J.D. Clinical findings in Bordetella pertussis infections: Results of a prospective multicenter surveillance study. Pediatrics 1997, 100, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiley, K.E.; Zuo, Y.; Macartney, K.K.; McIntyre, P.B. Sources of pertussis infection in young infants: A review of key evidence informing targeting of the cocoon strategy. Vaccine 2013, 31, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, M.; Nagai, M. Acellular pertussis vaccines in Japan: Past, present and future. Expert. Rev. Vaccines 2005, 4, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alghounaim, M.; Alsaffar, Z.; Alfraij, A.; Bin-Hasan, S.; Hussain, E. Whole-Cell and Acellular Pertussis Vaccine: Reflections on Efficacy. Med. Princ. Pract. 2022, 31, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pertussis—United States, 1997–2000. JAMA 2002, 287, 977–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Witt, M.A.; Katz, P.H.; Witt, D.J. Unexpectedly limited durability of immunity following acellular pertussis vaccination in preadolescents in a North American outbreak. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 54, 1730–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, K.M.; Decker, M.D.; Halsey, N.A.; Koblin, B.A.; Townsend, T.; Auerbach, B.; Karzon, D.T. Differences in antibody response to whole-cell pertussis vaccines. Pediatrics 1991, 88, 1019–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Melker, H.E.; Schellekens, J.F.; Neppelenbroek, S.E.; Mooi, F.R.; Rümke, H.C.; Conyn-van Spaendonck, M.A. Reemergence of pertussis in the highly vaccinated population of the Netherlands: Observations on surveillance data. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2000, 6, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Klein, N.P.; Bartlett, J.; Rowhani-Rahbar, A.; Fireman, B.; Baxter, R. Waning protection after fifth dose of acellular pertussis vaccine in children. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 1012–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustafsson, L.; Hessel, L.; Storsaeter, J.; Olin, P. Long-term follow-up of Swedish children vaccinated with acellular pertussis vaccines at 3, 5, and 12 months of age indicates the need for a booster dose at 5 to 7 years of age. Pediatrics 2006, 118, 978–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zasztowt-Sternicka, M.; Jagielska, A.M.; Nitsch-Osuch, A.S. Pertussis vaccination in pregnancy—Current data on safety and effectiveness. Ginekol. Pol. 2021, 92, 591–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murthy, S.; Godinho, M.A.; Lakiang, T.; Lewis, M.G.G.; Lewis, L.; Nair, N.S. Efficacy and safety of pertussis vaccination in pregnancy to prevent whooping cough in early infancy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 2018, CD013008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, C.M.; Rench, M.A.; Baker, C.J. Importance of timing of maternal combined tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) immunization and protection of young infants. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 56, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vygen-Bonnet, S.; Hellenbrand, W.; Garbe, E.; von Kries, R.; Bogdan, C.; Heininger, U.; Röbl-Mathieu, M.; Harder, T. Safety and effectiveness of acellular pertussis vaccination during pregnancy: A systematic review. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Available online: https://pulsmedycyny.pl/miesieczne-dziecko-zmarlo-na-krztusiec-dr-grzesiowski-ten-smutny-przypadek-pokazuje-na-czym-polega-odpornosc-populacyjna-1221240 (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- UKHSA. Research and Analysis. Confirmed Cases of Pertussis in England by Month. Updated 14 May 2024, Confirmed Cases of Pertussis in England by Month, to End March 2024. Applied to England. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/pertussis-epidemiology-in-england-2024/confirmed-cases-of-pertussis-in-england-by-month (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Statens Serum Institut. News November 2023. Increase in the Occurrence of Whooping Cough. Available online: https://en.ssi.dk/news/epi-news/2023/no-27---2023 (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Hua, C.Z.; He, H.Q.; Shu, Q. Resurgence of pertussis: Reasons and coping strategies. World J. Pediatr. 2024, 20, 639–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, M.; Zhang, G.; Yi, H. Unraveling the resurgence of pertussis: Insights into epidemiology and global health strategies. Pulmonology 2024, 30, 503–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakut, N.; Soysal, S.; Soysal, A.; Bakir, M. Knowledge and acceptance of influenza and pertussis vaccinations among pregnant women of low socioeconomic status in Turkey. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2019, 16, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.F.; Huang, S.Y.; Peng, H.H.; Chang, Y.L.; Chang, S.D.; Cheng, P.J.; Taiwan Prenatal Pertussis Immunization Program (PPIP) Collaboration Group. Factors affecting pregnant women’s decisions regarding prenatal pertussis vaccination: A decision-making study in the nationwide Prenatal Pertussis Immunization Program in Taiwan. Taiwan J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 59, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilca, L.M.; Cesari, E.; Tura, A.M.; Di Stefano, A.; Vidiri, A.; Cavaliere, A.F.; Cetin, I. Barriers and facilitators regarding influenza and pertussis maternal vaccination uptake: A multi-center survey of pregnant women in Italy. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2020, 247, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, F.; Ye, X.; Wang, Y.; Tang, N.; Feng, J.; Gao, Y.; Bao, M. Factors associated with pregnant women’s willingness to receive maternal pertussis vaccination in Guizhou Province, China: An exploratory cross-sectional study. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2024, 20, 2331870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Immink, M.M.; van der Maas, N.A.T.; de Melker, H.E.; Ferreira, J.A.; Bekker, M.N. Socio-psychological determinants of second trimester maternal pertussis vaccination acceptance in the Netherlands. Vaccine 2023, 41, 3446–3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratanasaengsuang, A.; Theerawut, W.; Chaithongwongwatthana, S. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Intention to Receive Pertussis Vaccine in Pregnant Women Attending the Antenatal Care Clinic, King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital. Thai J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2023, 30, 244–250. [Google Scholar]

- MacDougall, D.M.; Halperin, B.A.; Langley, J.M.; McNeil, S.A.; MacKinnon-Cameron, D.; Li, L.; Halperin, S.A. Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors of pregnant women approached to participate in a Tdap maternal immunization randomized, controlled trial. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2016, 12, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agricola, E.; Gesualdo, F.; Alimenti, L.; Pandolfi, E.; Carloni, E.; D’ambrosio, A.; Russo, L.; Campagna, I.; Ferretti, B.; Tozzi, A.E. Knowledge attitude and practice toward pertussis vaccination during pregnancy among pregnant and postpartum Italian women. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2016, 12, 1982–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshahrani, F.S.; Elnawawy, A.N.; Alwadie, A.M. Awareness and Acceptance of Pertussis Vaccination Among Pregnant Women in Taif Region, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus 2023, 15, e41726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hansen, B.T.; Winje, B.A.; Stålcrantz, J.; Greve-Isdahl, M. Predictors of maternal pertussis vaccination acceptance among pregnant women in Norway. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2024, 20, 2361499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hong, E.Y.; Kulkarni, K.; Gosavi, A.; Wong, H.C.; Singh, K.; Kale, A.S. Assessment of knowledge and attitude towards influenza and pertussis vaccination in pregnancy and factors affecting vaccine uptake rates: A cross-sectional survey. Singap. Med. J. 2023, 64, 513–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Building Vaccine Confidence: Strategies for Healthcare Providers. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/vaccine-confidence.html (accessed on 23 September 2024).

| Authors | Publication Year | Country | Study Population | Data Collection Method | Assessed Areas | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge of Pertussis | Knowledge of Vaccine | Attitude | ||||||

| 1. | Li et al. [27] | 2020 | Taiwan | 1809 pregnant women who had received prenatal care | Self-reported questionnaire at eight maternity hospitals | 48% considered pertussis a highly severe and highly contagious disease, which correlated with willingness to take the vaccine (p < 0.0001). | 62.58% considered maternal pertussis vaccination very effective, which correlated with willingness to take the vaccine (p < 0.0001). | The two most frequently selected reasons for accepting the vaccine were (1) belief that maternal Tdap vaccination could protect the infant from pertussis (35.3%) and (2) physician recommendation of prenatal Tdap (33.5%). The two most common reasons for declining the vaccine were (1) fear of possible vaccine adverse reactions to the fetus (43.8%) and (2) believing pertussis is not a severe disease among newborn infants (18%). |

| 2. | Vilca et al. [28] | 2020 | Italy | 743 pregnant women at least 32 weeks of gestation | Self-reported questionnaire at three care centers | Not analyzed | 51% were aware that maternal vaccination confers protection to newborns, and 17% believed that the pertussis vaccine can cause the disease in mother and infants. | For unvaccinated women, the main reason against maternal immunization was, “Vaccination was not recommended by any health-care provider (HCP)” (81%). As for the facilitators among vaccinated women, the main reason for accepting vaccines was “I want to protect my baby” (82%). |

| 3. | Jiang et al. [29] | 2024 | China | 564 pregnant women | Self-administered questionnaire in eleven hospital-based maternity units | Only 35.99% considered themselves susceptible to pertussis infection (p < 0.001). | Only 35.99% believed that vaccination can reduce the incidence of pertussis and its severity and that it will not affect maternal or fetal health (p < 0.001). | Intention to receive maternal vaccination was 36%. 35.99% agreed to take the vaccine because their physician recommended it (p < 0.001) |

| 4. | Immink et al. [30] | 2023 | The Netherlands | 1377 pregnant women | Online questionnaire | Not analyzed | Not analyzed | Intention to receive the vaccine was 94.8%. Nulliparous women had a significantly higher mean score for risk perception of pertussis susceptibility in their baby (3.1 vs. 2.9, p = 0.039) and a lower mean score for feeling a barrier in being vaccinated against combined vaccine components (2.5 vs. 3.0, p = 0.026). |

| 5. | Ratanasaengsuang et al. [31] | 2023 | Thailand | 387 pregnant women aged >18 and >20 weeks of gestation | Self-administered questionnaire | The mean score of knowledge about pertussis and the vaccine among participants was 11.8 ± 2.1, and 259 women (66.9%) correctly answered at least 10 out of 20 questions. | Analyzed altogether with knowledge of pertussis. | 45.5% expressed intention to receive the pertussis vaccine, and 52.2% were uncertain. The majority of participants had positive attitudes toward pertussis vaccination during pregnancy. 284 participants (73.4%) believed that maternal vaccination would protect their babies from pertussis, and 261 women (67.4%) strongly believed that vaccination during pregnancy was safe. |

| 6. | MacDougall et al. [32] | 2016 | Canada | 346 pregnant women | Self-administered questionnaire | 90.2% of participants had heard of pertussis. The mean number of correct answers to the 19 knowledge questions was 10.65 (95% confidence interval 10.28–11.01). | 45.1% “agreed” that maternal vaccination offers protection to newborns, and 17.1% “strongly agreed”. | 72.3% of participants agreed or strongly agreed that it was vital for children to be immunized against pertussis by 6 months of age, and 20.5% neither agreed nor disagreed with this statement. While attitudes about receiving the pertussis vaccine during pregnancy were generally favorable, many women neither agreed nor disagreed with these attitudinal statements. |

| 7. | Yakut et al. [26] | 2019 | Turkey | 465 pregnant women | Self-administered questionnaire at an outpatient clinic | In this study, only 24 (5%) participants had heard of pertussis, and only 26 (5.5%) knew that babies can contract pertussis. | Knowledge about the safety of the pertussis vaccine offered to babies was shown to have a positive influence on pertussis vaccination acceptance during pregnancy. | The acceptance rate of the pertussis vaccine was 11.2%. Participants who had a history of pertussis vaccinations during their adolescence or previous pregnancies were significantly more likely to accept a pertussis vaccination (p = 0.01 and p = 0.013, respectively). |

| 8. | Agricola et al. [33] | 2016 | Italy | 347 women: 164 pregnant women before the 27th week of gestation and 183 postpartum women within 30 days after delivery | Online questionnaire | Regarding knowledge about pertussis risks, nearly 35% of respondents did not know that infants <1 y of age represent the age group with the highest risk of infection. | Regarding knowledge of pertussis vaccination, more than half of the study population answered “undecided” to the specific questions. Among the analyzed population, 29% considered the vaccine as harmful for the fetus. | In the population of pregnant women, 34 (21%) expressed their willingness to vaccinate for pertussis during pregnancy. When asked if they would receive pertussis immunization during the current or a future pregnancy if recommended by an HCP, almost 34% stated the intention of getting the vaccine. Almost 48% declared to be uncertain, and more than 18% stated that they would not get the vaccination, even if they had received a recommendation from an HCP. |

| 9. | Alshahrani et al. [34] | 2023 | Saudi Arabia | 401 pregnant women aged more than 18 years | Interview questionnaire | It was reported that most of the participants ignored basic information about the nature of pertussis disease or its vaccine efficacy. | Most of the respondents doubted the safety of the pertussis vaccination during pregnancy. The majority did not know about the expected adverse reactions or safety levels of the pertussis vaccine during pregnancy or for their children. | We noted that 28 (7%) of the participants were recommended to have the pertussis vaccine, mainly by doctors and healthcare professionals (HCP), whereas seven (1.7%) were discouraged, mainly by relatives and friends, from taking it. Availability of the vaccine at no cost did not change the opinion of 55.1% of participants who refused to be vaccinated during pregnancy. |

| 10. | Hansen et al. [35] | 2024 | Norway | 1148 pregnant women 20–40 weeks of gestation | Online questionnaire | A total of 1101 (95.9%) of the women had heard of pertussis, while 47 (4.1%) women had not heard of or did not know whether they had heard of pertussis. | 53.3% were aware that maternal vaccination protects the infant against pertussis. Only 30.9% agreed that it is safe for pregnant women to receive it. | Women who agreed that maternal pertussis vaccination may increase the risk of birth defects or increase the risk of complicated pregnancy were less likely to accept vaccination against pertussis during pregnancy than were women who disagreed. Furthermore, women who disagreed with the statement “I worry that my newborn child will get pertussis” were significantly less likely to accept pertussis vaccination during pregnancy than were women who agreed. |

| 11. | Hong et al. [36] | 2023 | Singapore | 252 pregnant women | Self-administered questionnaire | Only 14% of women knew that the number of pertussis cases is on the rise. 52% of respondents considered pertussis more severe in newborns. | 35% of women believed that vaccines should be avoided in pregnancy. 65% were aware that maternal immunization can protect the child. | There was a generally positive attitude towards prenatal vaccination, with 63% of women being in favor of vaccination. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ługowski, F.; Babińska, J.; Urban, A.; Kacperczyk-Bartnik, J.; Bartnik, P.; Romejko-Wolniewicz, E.; Sieńko, J. Knowledge, Attitude, and Intention to Receive the Pertussis Vaccine in Pregnant Women: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3139. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233139

Ługowski F, Babińska J, Urban A, Kacperczyk-Bartnik J, Bartnik P, Romejko-Wolniewicz E, Sieńko J. Knowledge, Attitude, and Intention to Receive the Pertussis Vaccine in Pregnant Women: A Systematic Review. Healthcare. 2025; 13(23):3139. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233139

Chicago/Turabian StyleŁugowski, Franciszek, Julia Babińska, Aleksandra Urban, Joanna Kacperczyk-Bartnik, Paweł Bartnik, Ewa Romejko-Wolniewicz, and Jacek Sieńko. 2025. "Knowledge, Attitude, and Intention to Receive the Pertussis Vaccine in Pregnant Women: A Systematic Review" Healthcare 13, no. 23: 3139. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233139

APA StyleŁugowski, F., Babińska, J., Urban, A., Kacperczyk-Bartnik, J., Bartnik, P., Romejko-Wolniewicz, E., & Sieńko, J. (2025). Knowledge, Attitude, and Intention to Receive the Pertussis Vaccine in Pregnant Women: A Systematic Review. Healthcare, 13(23), 3139. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233139