A Flowchart to Guide Emergency Physicians to Order Radiological Imaging in Pregnant Patients: Findings from an Emergency Department Questionnaire

Highlights

- A significant majority (88.7%) of emergency department physicians report finding the management of pregnant trauma patients challenging and express a preference to avoid these cases.

- Physicians’ attitudes and decisions regarding imaging vary significantly based on their level of training and experience; Emergency Medicine Specialists and those with specific training are significantly more likely to order appropriate, immediate imaging for unstable patients regardless of gestational age.

- The widespread hesitation and practice variability among physicians, influenced by knowledge gaps and lack of guideline accessibility, may delay necessary diagnostics and compromise maternal–fetal outcomes.

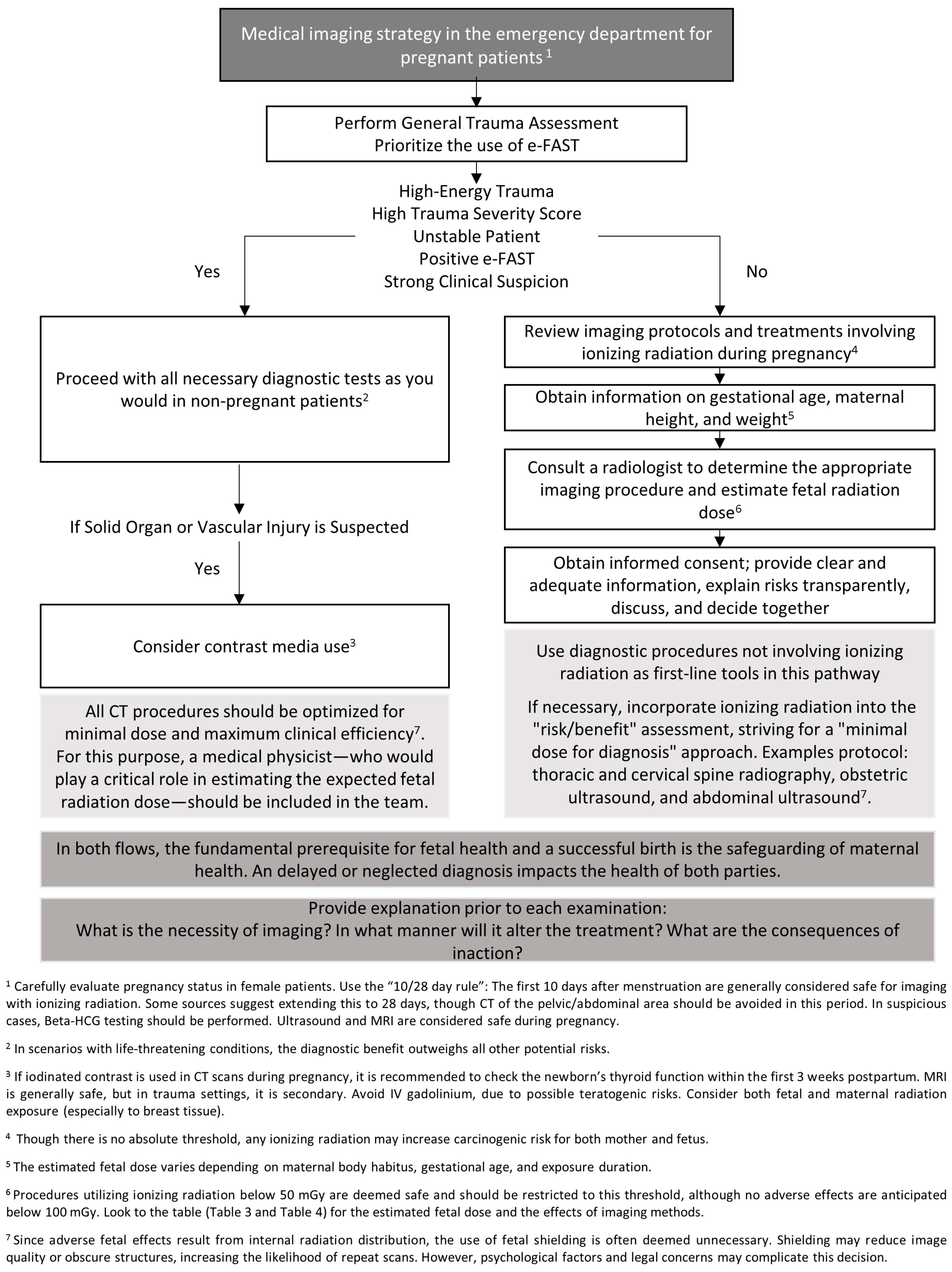

- These findings demonstrate an urgent need for standardized education and practical, evidence-based decision-support tools; consequently, this study proposes a novel clinical algorithm (flowchart) to guide imaging decisions in emergency settings.

Abstract

1. Introduction

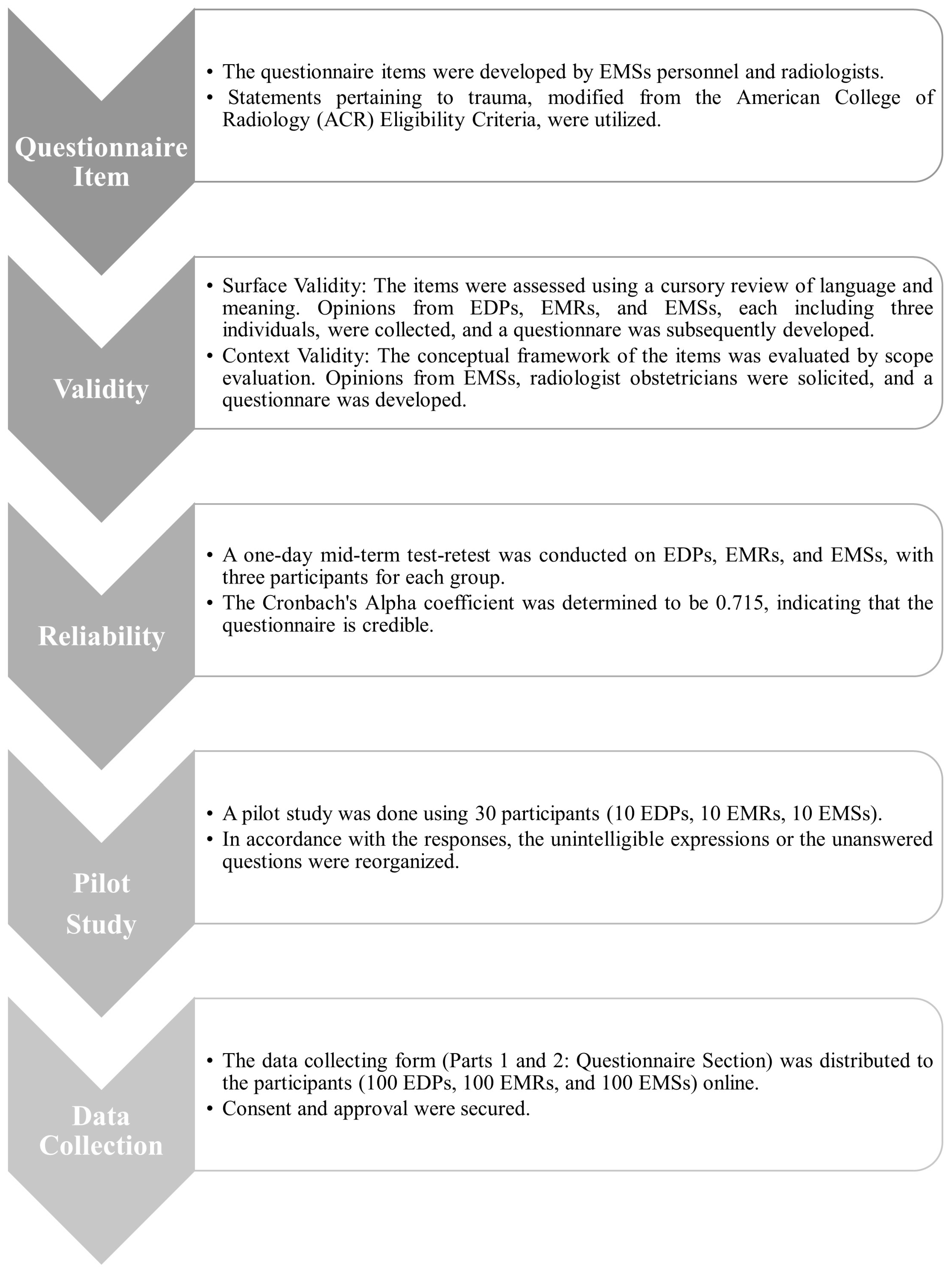

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants and Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Questionnaire Scoring

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographics

3.2. Attitudes and Training Regarding Pregnant Trauma Patients

3.3. Questionnaire Scores and Participants’ Own Pregnancy Experiences

3.4. Imaging Decisions in Unstable Pregnant Patients

3.5. Imaging Modality Preferences

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACR | American College of Radiology |

| Beta-HCG | Beta-human chorionic gonadotropin |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| ED | Emergency department |

| EDPs | Emergency department practitioners |

| EMSs | Emergency medicine specialists |

| EMRs | Emergency medicine residents |

| e-FAST | Extended Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma |

| Gy | Gray |

| IV | Intravenous |

| IQ | Intelligence quotient |

| MI | Medical imaging |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| Q | Question |

References

- Necarsulmer, J.; Reed, S.; Arhin, M.; Shastri, D.; Quig, N.; Yap, E.; Ho, J.; Sasaki-Adams, D. Cumulative Radiation Exposure in Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Single-Institution Analysis. World Neurosurg. 2022, 165, e432–e437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferretti, A.E.; Mercaldo, N.D.; Li, X.; Rehani, M.M. Assessing trends in patients undergoing recurrent CT examinations and cumulative doses. Eur. J. Radiol. 2025, 187, 112099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Atomic Energy Agency. Patient Radiation Exposure Monitoring in Medical Imaging; International Atomic Energy Agency: Vienna, Austria, 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, A.; Husson, O.; Drey, N.; Murray, I.; May, K.; Thurston, J.; Oyen, W. Ionising radiation exposure from medical imaging—A review of Patient’s (un) awareness. Radiography 2020, 26, e25–e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, B.; Dore, M.; Moullet, P. Diagnostic Imaging: Appropriate and Safe Use. Am. Fam. Physician 2021, 103, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Kim, K.; Lee, K.H.; Kim, K.P.; Kim, Y.J.; Park, C.; Kang, C.; Lee, S.H.; Jeong, J.H.; Rhee, J.E. Perception of radiation dose and potential risks of computed tomography in emergency department medical personnel. Clin. Exp. Emerg. Med. 2015, 2, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsubaie, F.H.; Abujamea, A.H. Knowledge and Perception of Radiation Risk from Computed Tomography Scans Among Patients Attending an Emergency Department. Cureus 2024, 16, e52687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seven, M.; Yigin, A.K.; Agirbasli, D.; Alay, M.T.; Kirbiyik, F.; Demir, M. Radiation exposure in pregnancy: Outcomes, perceptions and teratological counseling in Turkish women. Ann. Saudi Med. 2022, 42, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albakri, A.A.; Alzahrani, M.M.; Alghamdi, S.H. Medical Imaging in Pregnancy: Safety, Appropriate Utilization, and Alternative Modalities for Imaging Pregnant Patients. Cureus 2024, 16, e54346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitan, A.F.; Sanderud, A. What information did pregnant women want related to risks and benefits attending X-ray examinations? J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Sci. 2021, 52, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, S.; Okazaki, K.; Nakano, H.; Ishii, K.; Kyozuka, H.; Murata, T.; Fujimori, K.; Goto, A.; Yasumura, S.; Ota, M.; et al. Effects of External Radiation Exposure on Perinatal Outcomes in Pregnant Women After the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant Accident: The Fukushima Health Management Survey. J. Epidemiol. 2022, 32, S104–S114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makkia, R.; Nelson, K.; Zaidi, H.; Dingfelder, M. Hybrid computational pregnant female phantom construction for radiation dosimetry applications. Biomed. Phys. Eng. Express 2022, 8, 065015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shetty, M.K. Abdominal computed tomography during pregnancy: A review of indications and fetal radiation exposure issues. Semin. Ultrasound CT MRI 2010, 31, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgioti, C.; Konidari, M.; Gourtsoyianni, S.; Moulopoulos, L.A. Imaging during pregnancy: What the radiologist needs to know. Diagn. Interv. Imaging 2021, 102, 593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abback, P.S.; Benchetrit, A.; Delhaye, N.; Daire, J.L.; James, A.; Neuschwander, A.; Boutonnet, M.; Cook, F.; Vinour, H.; Hanouz, J.L.; et al. Multiple trauma in pregnant women: Injury assessment, fetal radiation exposure and mortality. A multicentre observational study. Scand. J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 2023, 31, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainprize, J.G.; Yaffe, M.J.; Chawla, T.; Glanc, P. Effects of ionizing radiation exposure during pregnancy. Abdom. Radiol. 2023, 48, 1564–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No. 723: Guidelines for Diagnostic Imaging During Pregnancy and Lactation. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 130, e210–e216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaloglu, E.; McDonnell, D.; Chu, J.; Lecky, F.; Porter, K. Epidemiology and outcomes of pregnancy and obstetric complications in trauma in the United Kingdom. Injury 2016, 47, 184–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.; De Jesus, O. Radiation Effects on the Fetus. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- American College of Radiology. ACR Appropriateness Criteria. Available online: https://gravitas.acr.org/acportal (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- MacDermott, R.; Berger, F.H.; Phillips, A.; Robins, J.A.; O’Keeffe, M.E.; Mughli, R.A.; MacLean, D.B.; Liu, G.; Heipel, H.; Nathens, A.B.; et al. Initial Imaging of Pregnant Patients in the Trauma Bay-Discussion and Review of Presentations at a Level-1 Trauma Centre. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paterick, T.E.; Patel, N.; Tajik, A.J.; Chandrasekaran, K. Improving health outcomes through patient education and partnerships with patients. Proc. Bayl. Univers. Med. Cent. 2017, 30, 112–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Welie, N.; Portela, M.; Dreyer, K.; Schoonmade, L.J.; van Wely, M.; Mol, B.W.J.; van Trotsenburg, A.S.P.; Lambalk, C.B.; Mijatovic, V.; Finken, M.J.J. Iodine contrast prior to or during pregnancy and neonatal thyroid function: A systematic review. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2021, 184, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fällmar, D.; Granberg, T.; Kits, A.; Nilsson, M.; Sundström, K.; Åslund, P.E.; Carlqvist, J.; Wikström, J.; Björkman-Burtscher, I.; Blystad, I. Conditions for performing CT and MRI scans in pregnant and lactating patients. Lakartidningen 2023, 120, 23103. [Google Scholar]

- Qamar, S.R.; Green, C.R.; Ghandehari, H.; Holmes, S.; Hurley, S.; Khumalo, Z.; Mohammed, M.F.; Ziesmann, M.; Jain, V.; Thavanathan, R.; et al. CETARS/CAR Practice Guideline on Imaging the Pregnant Trauma Patient. Can. Assoc. Radiol. J. 2024, 75, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabehdar Maralani, P.; Kapadia, A.; Liu, G.; Moretti, F.; Ghandehari, H.; Clarke, S.E.; Wiebe, S.; Garel, J.; Ertl-Wagner, B.; Hurrell, C.; et al. Canadian Association of Radiologists Recommendations for the Safe Use of MRI During Pregnancy. Can. Assoc. Radiol. J. 2021, 73, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathur, S.; Pillenahalli Maheshwarappa, R.; Fouladirad, S.; Metwally, O.; Mukherjee, P.; Lin, A.; Bharatha, A.; Nicolaou, S.; Ditkofsky, N. Emergency Imaging in Pregnancy and Lactation. Can. Assoc. Radiol. J. 2020, 71, 084653712090648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiebich, M.; Block, A.; Borowski, M.; Geworski, L.; Happel, C.; Kamp, A.; Lenzen, H.; Mahnken, A.H.; Müller, W.U.; Östreicher, G.; et al. Prenatal radiation exposure in diagnostic and interventional radiology. RoFo 2021, 193, 778–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Boyd, B. Diagnostic Imaging of Pregnant Women and Fetuses: Literature Review. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saada, M.; Sanchez-Jimenez, E.; Roguin, A. Risk of ionizing radiation in pregnancy: Just a myth or a real concern? Europace 2023, 25, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picone, C.; Fusco, R.; Tonerini, M.; Fanni, S.C.; Neri, E.; Brunese, M.C.; Grassi, R.; Danti, G.; Petrillo, A.; Scaglione, M.; et al. Dose Reduction Strategies for Pregnant Women in Emergency Settings. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimi, Y.; Mansouri, Z.; Sun, C.; Sanaat, A.; Yazdanpanah, M.; Shooli, H.; Nkoulou, R.; Boudabbous, S.; Zaidi, H. Deep learning-based segmentation of ultra-low-dose CT images using an optimized nnU-Net model. Radiol. Medica 2025, 130, 723–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.V.; Ramanathan, S.; Venugopalan, P. Chest imaging in pregnant patients with COVID-19: Recommendations, justification, and optimization. Acta Radiol. Open 2022, 11, 20584601221077394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radiological Society of The Netherlands. Guideline Safe Use of Contrast Media Part 3; Radiological Society of The Netherlands: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Perelli, F.; Turrini, I.; Giorgi, M.G.; Renda, I.; Vidiri, A.; Straface, G.; Scatena, E.; D’Indinosante, M.; Marchi, L.; Giusti, M.; et al. Contrast Agents during Pregnancy: Pros and Cons When Really Needed. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atwell, T.D.; Lteif, A.N.; Brown, D.L.; McCann, M.; Townsend, J.E.; LeRoy, A.J. Neonatal Thyroid Function After Administration of IV Iodinated Contrast Agent to 21 Pregnant Patients. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2008, 191, 268–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, I.; Slesinger, T.L. Radiation Exposure in Pregnancy. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- McCollough, C.H.; Schueler, B.A.; Atwell, T.D.; Braun, N.N.; Regner, D.M.; Brown, D.L.; LeRoy, A.J. Radiation exposure and pregnancy: When should we be concerned? Radiographics 2007, 27, 909–917; discussion 917–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, S. Diagnostic imaging in pregnancy: Making informed decisions. Obstet. Med. 2019, 12, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groen, R.S.; Bae, J.Y.; Lim, K.J. Fear of the unknown: Ionizing radiation exposure during pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 206, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eibschutz, L.; Lu, M.Y.; Jannatdoust, P.; Judd, A.C.; Justin, C.A.; Fields, B.K.K.; Demirjian, N.L.; Rehani, M.; Reddy, S.; Gholamrezanezhad, A. Emergency imaging protocols for pregnant patients: A multi-institutional and multi- specialty comparison of physician education. Emerg. Radiol. 2024, 31, 851–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrigano, R.R.; Abrão, K.C.; Puchnick, A.; Regacini, R. Evaluation of non-radiologist physicians’ knowledge on aspects related to ionizing radiation in imaging. Radiol. Bras. 2014, 47, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Woo, S.; Seol, S.; Kim, D.; Wee, J.; Choi, S.; Jeong, W.; Oh, S.; Kyong, Y.; Kim, S. Physician and nurse knowledge about patient radiation exposure in the emergency department. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2016, 19, 502–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnapalan, S.; Bona, N.; Chandra, K.; Koren, G. Physicians’ perceptions of teratogenic risk associated with radiography and CT during early pregnancy. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2004, 182, 1107–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, C.E.; Salloum, J.; Varon, A.J.; Toledo, P.; Dudaryk, R. The Management of Pregnant Trauma Patients: A Narrative Review. Anesth. Analg. 2023, 136, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abushouk, A.I.; Sanei Taheri, M.; Pooransari, P.; Mirbaha, S.; Rouhipour, A.; Baratloo, A. Pregnancy Screening before Diagnostic Radiography in Emergency Department; an Educational Review. Emergency 2017, 5, e60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rocha, A.P.C.; Carmo, R.L.; Melo, R.F.Q.; Vilela, D.N.; Leles-Filho, O.S.; Costa-Silva, L. Imaging evaluation of nonobstetric conditions during pregnancy: What every radiologist should know. Radiol. Bras. 2020, 53, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Commission on Radiological Protection. Pregnancy and Medical Radiation; ICRP, Ed.; International Commission on Radiological Protection: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wiles, R.; Hankinson, B.; Benbow, E.; Sharp, A. Making decisions about radiological imaging in pregnancy. BMJ 2022, 377, e070486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACR Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media. Administration of Contrast Media to Pregnant or Potentially Pregnant Patients. Available online: https://www.acr.org/Clinical-Resources/Clinical-Tools-and-Reference/Contrast-Manual (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- The U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Recommends Thyroid Monitoring in Babies and Young Children Who Receive Injections of Iodine-Containing Contrast Media for Medical Imaging; The U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2025.

- Fujibuchi, T.; Matsubara, K.; Hamada, N. NCRP Statement No. 13 “NCRP Recommendations for Ending Routine Gonadal Shielding During Abdominal and Pelvic Radiography” and Its Accompanying Documents: Underpinnings and Recent Developments. Jpn. J. Health Phys. 2022, 56, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frangione, B.; Hinton, P.; Villeneuve, P.J. Low-dose ionizing radiation and adverse birth outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2023, 96, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameters | n | % | Questionnaire Score (Mean ± SD) | Statistical Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 198 | 66 | 6.65 ± 1.90 | p = 0.841 t = −0.201 |

| Female | 102 | 34 | 6.70 ± 1.64 | ||

| Marital status | Married | 188 | 62.7 | 6.60 ± 1.57 | p= 0.615 t = −0.540 |

| Unmarried | 112 | 37.3 | 6.71 ± 1.94 | ||

| Have child | Yes | 128 | 42.7 | 6.79 ± 2.06 | p= 0.314 t = 1.008 |

| No | 172 | 57.3 | 6.58 ± 1.60 | ||

| Title | Emergency department practitioner | 100 | 33.3 | 6.18 ± 1.64 | p < 0.001 * F = 12.110 L = 0.616 |

| Emergency medicine resident | 100 | 33.3 | 6.47 ± 1.80 | ||

| Emergency medicine specialist | 100 | 33.3 | 7.35 ± 1.79 | ||

| <1 | 47 | 15.7 | 6.00 ± 1.58 | p = 0.010 ** F = 3.556 L = 0.013 | |

| Experience (year) | ≥1 and <5 | 86 | 28.7 | 6.52 ± 1.70 | |

| ≥5 and <10 | 61 | 20.3 | 6.89 ± 1.56 | ||

| ≥10 | 106 | 35.3 | 6.95 ± 2.04 |

| Parameters | n (%) | Questionnaire Score (Mean ± SD) | Statistical Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emergency service management of traumatized pregnant patients is challenging and I would not like to encounter this patient group. | Yes | 266 (88.7) | 6.70 ± 1.79 | p = 0.443 t = 0.769 |

| No | 34 (11.3) | 6.44 ± 2.28 | ||

| If you are a woman, did you experience a situation that necessitated radiologic imaging during your pregnancy? If you are a man, did you confront that same situation during your wife’s pregnancy? (n = 187) | Yes | 29 (15.5) | 6.55 ± 1.95 | p = 0.897 F = 0.109 |

| No | 158 (84.5) | 6.71 ± 2.09 | ||

| (If you have encountered a situation that requires radiological imaging) Did you agree to have imaging? (n = 29) | Yes | 25 (86.2) | 6.76 ± 1.80 | p = 0.155 t = 1.462 |

| No | 4 (13.8) | 5.75 ± 2.63 | ||

| Have you read any books or scientific literature on trauma management in pregnant women and the use of imaging methods? | Yes | 117 (39.0) | 7.16 ± 1.68 | p < 0.001 t = 3.871 |

| No | 183 (61.0) | 6.35 ± 1.83 | ||

| Have you taken courses on trauma management in pregnant women and the use of imaging methods? | Yes | 82 (27.3) | 7.12 ± 1.80 | p = 0.007 t = 2.693 |

| No | 218 (72.7) | 6.50 ± 1.79 | ||

| Have you attended a course or a certified program on trauma management in pregnant women and the use of imaging methods? | Yes | 23 (7.7) | 7.39 ± 1.58 | p = 0.046 t = 2.003 |

| No | 277 (92.3) | 6.61 ± 1.82 |

| Questions and Distribution | Agree | Disagree | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | In traumatizedtraumatised, unstable pregnant patients, laboratory tests should be expected first after physical examination. | EDPs (n) | 68 | 32 |

| EMRs (n) | 44 | 56 | ||

| EMSs (n) | 72 | 28 | ||

| Total (n, %) | 140, 46.3 | 160, 53.3 | ||

| Q2 | Informed consent must be obtained in traumatized, unstable pregnant patients, prior to imaging procedures involving ionizing radiation. | EDPs (n) | 91 | 9 |

| EMRs (n) | 88 | 12 | ||

| EMSs (n) | 72 | 28 | ||

| Total (n, %) | 251, 83.7 | 49, 16.3 | ||

| Q3 | In pregnant patients, it is important to order examinations based on the estimated fetal dose of the radiologic imaging procedure. | EDPs (n) | 74 | 26 |

| EMRs (n) | 80 | 20 | ||

| EMSs (n) | 89 | 11 | ||

| Total (n, %) | 240, 80.0 | 60, 20.0 | ||

| Q4 | In traumatized pregnant patients, if there is thoracic or abdominal trauma, CT imaging with IV iodinated contrast material should be performed. | EDPs (n) | 21 | 79 |

| EMRs (n) | 34 | 66 | ||

| EMSs (n) | 39 | 61 | ||

| Total (n, %) | 94, 31.3 | 206, 68.7 | ||

| Q5 | In traumatized pregnant patients, MR imaging with gadolinium can be performed. | EDPs (n) | 27 | 73 |

| EMRs (n) | 25 | 75 | ||

| EMSs (n) | 33 | 67 | ||

| Total (n, %) | 85, 28.3 | 215, 71.7 | ||

| Q6 | If the pregnant patient has given birth after diagnostic imaging with iodinated contrast media, I recommend that breastfeeding be discontinued. | EDPs (n) | 75 | 25 |

| EMRs (n) | 70 | 30 | ||

| EMSs (n) | 59 | 41 | ||

| Total (n, %) | 204, 68.0 | 96, 32.0 | ||

| Q7 | In traumatized pregnant patients, diagnostic imaging with a single dose of X-ray is not objectionable. | EDPs (n) | 39 | 61 |

| EMRs (n) | 44 | 56 | ||

| EMSs (n) | 59 | 41 | ||

| Total (n, %) | 142, 47.3 | 158, 52.7 | ||

| Q8 | In traumatized pregnant patients, a single dose CT (brain, cervical, thoracic, abdominal) can be easily ordered if necessary. | EDPs (n) | 81 | 19 |

| EMRs (n) | 79 | 21 | ||

| EMSs (n) | 82 | 18 | ||

| Total (n, %) | 242, 80.7 | 58, 19.3 | ||

| Q9 | Previous radiologic imaging for another reason may increase the cumulative fetal radiation dose in pregnant women, and it is important to question this situation. | EDPs (n) | 95 | 5 |

| EMRs (n) | 94 | 6 | ||

| EMSs (n) | 89 | 11 | ||

| Total (n, %) | 278, 92.7 | 22, 7.3 | ||

| Q10 | In traumatized pregnant patients, I can easily recommend MRI regardless of the gestational week. | EDPs (n) | 68 | 32 |

| EMRs (n) | 70 | 30 | ||

| EMSs (n) | 72 | 28 | ||

| Total (n, %) | 210, 70.0 | 90, 30.0 | ||

| Q11 | If the traumatized pregnant woman is unstable or if there is evidence of severe trauma in the patient, it is important to choose CT as the first choice when choosing between MR or CT. | EDPs (n) | 45 | 55 |

| EMRs (n) | 63 | 37 | ||

| EMSs (n) | 74 | 26 | ||

| Total (n, %) | 182, 60.7 | 118, 39.3 | ||

| Q12 | In the presence of high clinical suspicion of Pulmonary Embolism in a pregnant patient or in the presence of DVT, I would not hesitate to order Pulmonary CT angiography for the diagnosis of Pulmonary Embolism. | EDPs (n) | 44 | 56 |

| EMRs (n) | 28 | 72 | ||

| EMSs (n) | 38 | 62 | ||

| Total (n, %) | 110, 36.7 | 190, 63.3 | ||

| Period | Week After Fertilization | Estimated Threshold Dose | Effect of Ionizing Radiation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational | 0–2 | 50–100 mGy | Death of embryo or no consequence |

| 2–8 | 200 mGy | Congenital anomalies | |

| 200–250 mGy | Growth restriction | ||

| Fetal | 8–15 | 60–310 mGy | Severe intellectual disability (high risk) |

| 200 mGy | Microcephaly | ||

| 25 IQ loss per 1000 mGy | Intellectual deficit | ||

| 15–25 | 250–280 mGy | Severe intellectual disability (low risk) |

| Dose Classification | Radiography | mGy | Computed Tomography | mGy | Nuclear Medicine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose classification Very low <0.1 mGy | Any extremity | <0.001 | Head or neck | 0.001–0.1 | |

| Cervical spine (two view) | <0.001 | ||||

| Chest (two view) | 0.0005–0.001 | ||||

| Low to moderate 0.1–10 mGy | Abdominal | 0.1–3.0 | Chest or pulmonary angiography | 0.01–0.66 | Low-dose perfusion scintigraphy |

| Lumbar spine | 1.0–10 | Technetium- 99m bone scintigraphy | |||

| Pulmonary digital subtraction angiography | |||||

| High 10–50 mGy | Abdominal | 1.3–35 | |||

| Pelvic | 10–50 | ||||

| 18F-PET/CT (Whole body) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tekin, F.C.; Ataş, A.E.; Köse, F.; Acar, D. A Flowchart to Guide Emergency Physicians to Order Radiological Imaging in Pregnant Patients: Findings from an Emergency Department Questionnaire. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3138. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233138

Tekin FC, Ataş AE, Köse F, Acar D. A Flowchart to Guide Emergency Physicians to Order Radiological Imaging in Pregnant Patients: Findings from an Emergency Department Questionnaire. Healthcare. 2025; 13(23):3138. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233138

Chicago/Turabian StyleTekin, Fatih Cemal, Abdullah Enes Ataş, Fulya Köse, and Demet Acar. 2025. "A Flowchart to Guide Emergency Physicians to Order Radiological Imaging in Pregnant Patients: Findings from an Emergency Department Questionnaire" Healthcare 13, no. 23: 3138. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233138

APA StyleTekin, F. C., Ataş, A. E., Köse, F., & Acar, D. (2025). A Flowchart to Guide Emergency Physicians to Order Radiological Imaging in Pregnant Patients: Findings from an Emergency Department Questionnaire. Healthcare, 13(23), 3138. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233138