Prognostic Value of the Preoperative Prognostic Nutritional Index in Predicting Survival Outcomes After Curative Surgery for Colorectal Cancer

Highlights

- Nutritional optimization before surgery might improve outcomes.

- More careful selection or tailoring of adjuvant therapy may be needed, possibly supported by enhanced supportive care.

- Enhanced postoperative monitoring and follow-up may help detect complications early or manage recurrence risk more promptly.

- Discussions with patients about prognosis and treatment trade-offs could incorporate PNI as part of personalized risk communication.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Ethical Approval

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Operative and Pathological Findings

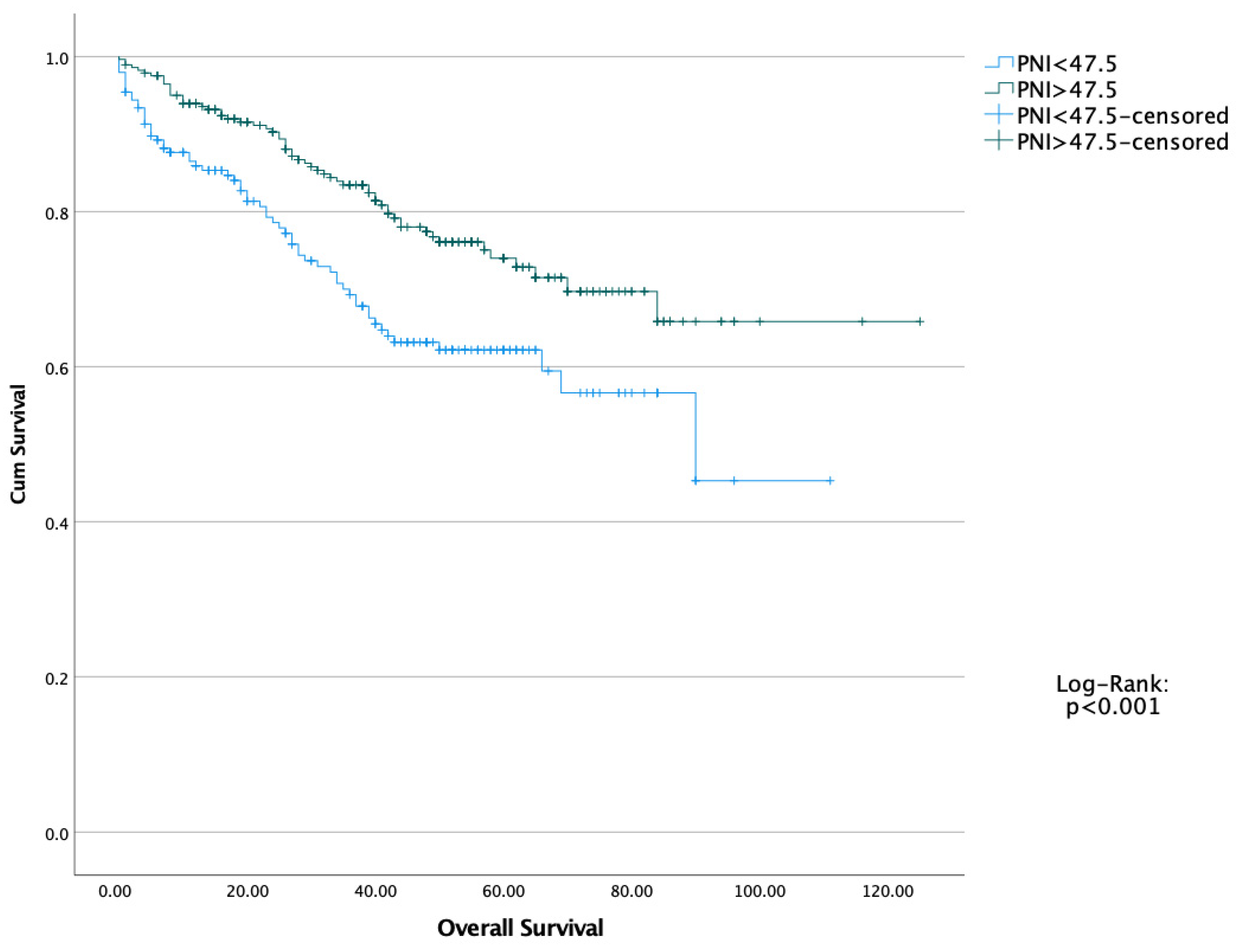

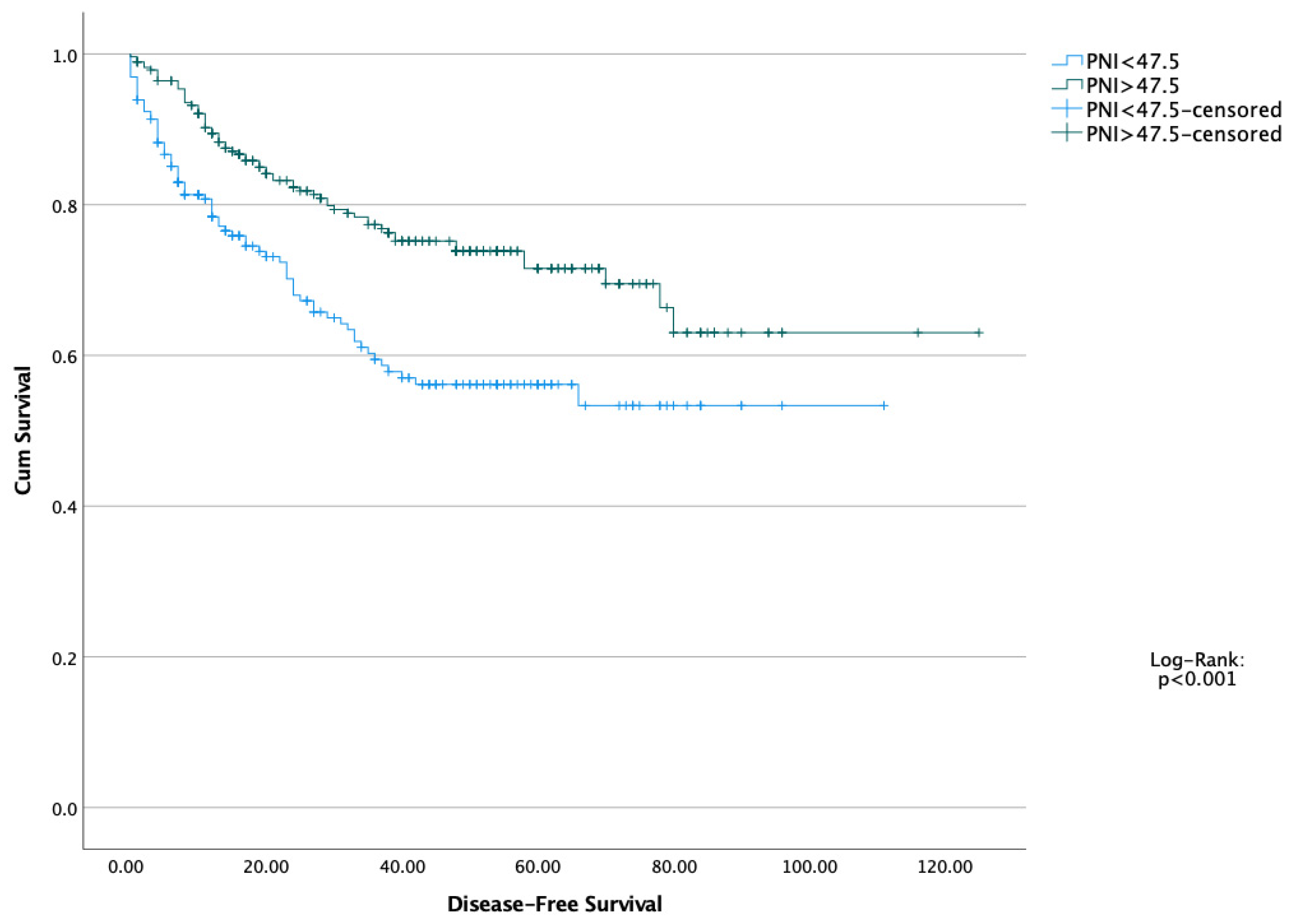

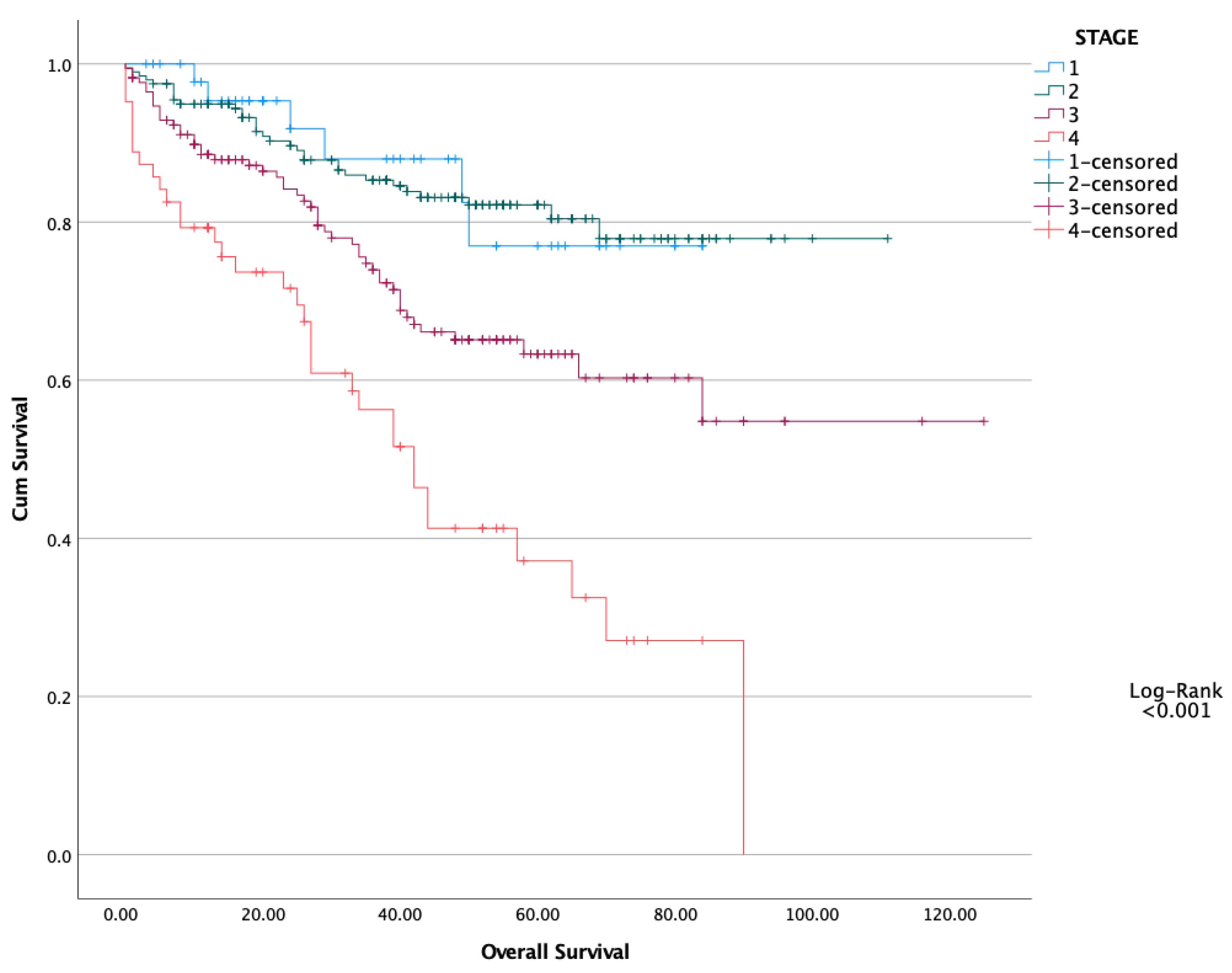

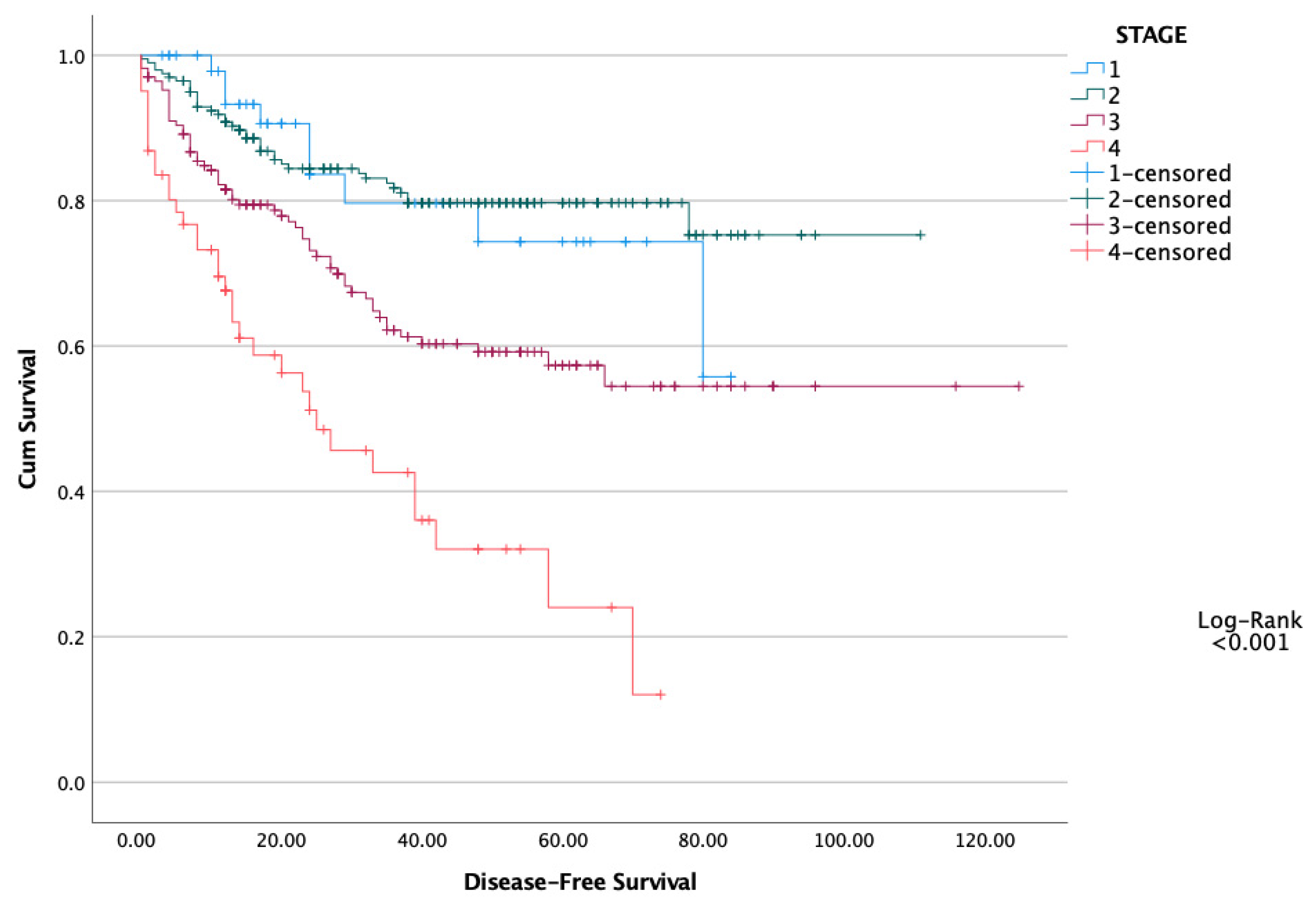

3.3. Survival Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiser, M.R. AJCC 8th Edition: Colorectal Cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 25, 1454–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMillan, D.C. The systemic inflammation-based Glasgow Prognostic Score: A decade of experience in patients with cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2013, 39, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fearon, K.; Strasser, F.; Anker, S.D.; Bosaeus, I.; Bruera, E.; Fainsinger, R.L.; Jatoi, A.; Loprinzi, C.; MacDonald, N.; Mantovani, G.; et al. Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: An international consensus. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templeton, A.J.; McNamara, M.G.; Šeruga, B.; Vera-Badillo, F.E.; Aneja, P.; Ocaña, A.; Leibowitz-Amit, R.; Sonpavde, G.; Knox, J.J.; Tran, B.; et al. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014, 106, dju124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, M.J.; McMillan, D.C.; Morrison, D.S.; Fletcher, C.D.; Horgan, P.G.; Clarke, S.J. A derived neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predicts survival in patients with cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2012, 107, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzby, G.P.; Mullen, J.L.; Matthews, D.C.; Hobbs, C.L.; Rosato, E.F. Prognostic nutritional index in gastrointestinal surgery. Am. J. Surg. 1980, 139, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eo, W.K.; Chang, H.J.; Suh, J.; Ahn, J.; Shin, J.; Hur, J.-Y.; Kim, G.Y.; Lee, S.; Park, S.; Lee, S. The Prognostic Nutritional Index Predicts Survival and Identifies Aggressiveness of Gastric Cancer. Nutr. Cancer 2015, 67, 1260–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Qi, Q.; Sun, M.; Chen, H.; Wang, P.; Chen, Z. Prognostic nutritional index predicts survival and correlates with systemic inflammatory response in advanced pancreatic cancer. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. J. Eur. Soc. Surg. Oncol. Br. Assoc. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 41, 1508–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Chen, S.; Xu, J.; Li, G.; He, Y. The prognostic significance of the prognostic nutritional index in cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 140, 1537–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohri, Y.; Inoue, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Hiro, J.; Uchida, K.; Kusunoki, M. Prognostic nutritional index predicts postoperative outcome in colorectal cancer. World J. Surg. 2013, 37, 2688–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dindo, D.; Demartines, N.; Clavien, P.A. Classification of surgical complications: A new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann. Surg. 2004, 240, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.; Lis, C.G. Pretreatment serum albumin as a predictor of cancer survival: A systematic review of the epidemiological literature. Nutr. J. 2010, 9, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazha, B.; Moussaly, E.; Zaarour, M.; Weerasinghe, C.; Azab, B. Hypoalbuminemia in colorectal cancer prognosis: Nutritional marker or inflammatory surrogate? World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2015, 7, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichling, C.; Taieb, J.; Derangere, V.; Klopfenstein, Q.; Le Malicot, K.; Gornet, J.-M.; Becheur, H.; Fein, F.; Cojocarasu, O.; Kaminsky, M.C.; et al. Artificial intelligence-guided tissue analysis combined with immune infiltrate assessment predicts stage III colon cancer outcomes in PETACC08 study. Gut 2020, 69, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazici, H.; Eren Kayaci, A.; Sevindi, H.I.; Attaallah, W. Should we consider Systemic Inflammatory Response Index (SIRI) as a new diagnostic marker for rectal cancer? Discov. Oncol. 2024, 15, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanyuda, A.; Ogino, S.; Qian, Z.R.; Nishihara, R.; Song, M.; Mima, K.; Inamura, K.; Masugi, Y.; Wu, K.; Meyerhardt, J.A.; et al. Body mass index and risk of colorectal cancer according to tumor lymphocytic infiltrate. Int. J. Cancer 2016, 139, 854–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Zhao, G.; Yu, T.; An, Q.; Yang, H.; Xiao, G. Preoperative Prognostic Nutritional Index Correlates with Severe Complications and Poor Survival in Patients with Colorectal Cancer Undergoing Curative Laparoscopic Surgery: A Retrospective Study in a Single Chinese Institution. Nutr. Cancer 2017, 69, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, U.O.; Rockall, T.A.; Wexner, S.; How, K.Y.; Emile, S.; Marchuk, A.; Fawcett, W.J.; Sioson, M.; Riedel, B.; Chahal, R.; et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in elective colorectal surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society recommendations 2025. Surgery 2025, 184, 109397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weimann, A.; Bezmarevic, M.; Braga, M.; Correia, M.I.T.D.; Funk-Debleds, P.; Gianotti, L.; Gillis, C.; Hübner, M.; Inciong, J.F.B.; Jahit, M.S.; et al. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition in surgery—Update 2025. Clin. Nutr. 2025, 53, 222–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKechnie, T.; Kazi, T.; Jessani, G.; Shi, V.; Sne, N.; Doumouras, A.; Hong, D.; Eskicioglu, C. The use of preoperative enteral immunonutrition in patients undergoing elective colorectal cancer surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Color. Dis. Off. J. Assoc. Coloproctol. Gt. Britain Irel. 2025, 27, e70061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chona Chona, M.; López Basto, L.M.; Pinzón Ospina, C.; Pardo Coronado, A.C.; Guzmán Silva, M.P.; Marín, M.; Vallejos, A.; Castro Osmán, G.E.; Saavedra, C.; Díaz Rojas, J.; et al. Preoperative immunonutrition and postoperative outcomes in patients with cancer undergoing major abdominal surgery: Retrospective cohort study. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2025, 65, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.C.; Corkins, M.R.; Malone, A.; Miller, S.; Mogensen, K.M.; Guenter, P.; Jensen, G.L. The Use of Visceral Proteins as Nutrition Markers: An ASPEN Position Paper. Nutr. Clin. Pract. Off. Publ. Am. Soc. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2021, 36, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, A.; Hanna, M.H.; Moghadamyeghaneh, Z.; Stamos, M.J. Implications of preoperative hypoalbuminemia in colorectal surgery. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2016, 8, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haskins, I.N.; Baginsky, M.; Amdur, R.L.; Agarwal, S. Preoperative hypoalbuminemia is associated with worse outcomes in colon cancer patients. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 1333–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cederholm, T.; Jensen, G.L.; Correia, M.I.T.D.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Fukushima, R.; Higashiguchi, T.; Baptista, G.; Barazzoni, R.; Blaauw, R.; Coats, A.J.S.; et al. GLIM criteria for the diagnosis of malnutrition—A consensus report from the global clinical nutrition community. J. Cachexia. Sarcopenia Muscle 2019, 10, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, J.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, X.; Chen, G.; Wan, D.; Lu, Z.; Pan, Z. Prognostic value of preoperative prognostic nutritional index and its associations with systemic inflammatory response markers in patients with stage III colon cancer. Chin. J. Cancer 2017, 36, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibutani, M.; Maeda, K.; Nagahara, H.; Ohtani, H.; Iseki, Y.; Ikeya, T.; Sugano, K.; Hirakawa, K. The prognostic significance of the postoperative prognostic nutritional index in patients with colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, G.T.; Han, J.; Cho, M.S.; Hur, H.; Min, B.S.; Lee, K.Y.; Kim, N.K. Impact of the prognostic nutritional index on the recovery and long-term oncologic outcome of patients with colorectal cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 143, 1235–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskinkilic, M.; Semiz, H.S.; Ataca, E.; Yavuzsen, T. The prognostic value of immune-nutritional status in metastatic colorectal cancer: Prognostic Nutritional Index (PNI). Support. Care Cancer Off. J. Multinatl. Assoc. Support. Care Cancer 2024, 32, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Chen, F.; Liang, L.; Jiang, W.; Liu, X.; Wang, D.; Wu, Y.; Chen, J.; Guan, G.; Peng, X.E. A novel inflammation-related prognostic biomarker for predicting the disease-free survival of patients with colorectal cancer. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 20, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebig, C.; Ayala, G.; Wilks, J.; Verstovsek, G.; Liu, H.; Agarwal, N.; Berger, D.H.; Albo, D. Perineural invasion is an independent predictor of outcome in colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 5131–5137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayat, Z.; Govindarajan, A.; Victor, J.C.; Kennedy, E.D. Impact of structured multicentre enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol implementation on length of stay after colorectal surgery. BJS Open 2024, 8, zrae094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tweed, T.T.T.; Woortman, C.; Tummers, S.; Bakens, M.J.A.M.; van Bastelaar, J.; Stoot, J.H.M.B. Reducing hospital stay for colorectal surgery in ERAS setting by means of perioperative patient education of expected day of discharge. Int. J. Colorectal. Dis. 2021, 36, 1535–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slim, N.; Teng, W.H.; Shakweh, E.; Sylvester, H.-C.; Awad, M.; Schembri, R.; Hermena, S.; Chowdhary, M.; Oodit, R.; Francis, N.K. Enhanced recovery programme after colorectal surgery in high-income and low-middle income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Surg. 2023, 109, 3609–3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N: 489 | PNI < 47.5 (N: 201) | PNI > 47.5 (N: 288) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age [Median (IQR)] | 67 (IQR: 16) | 62 (IQR: 13) | <0.001 |

| Gender (%) | 0.435 | ||

| Male | 108 (54%) | 165 (57%) | |

| Female | 93 (46%) | 123 (43%) | |

| Comorbid Diseases | 0.411 | ||

| Presence | 124 (62%) | 167 (58%) | |

| Absence | 77 (38%) | 121 (42%) | |

| Comorbid Diseases | |||

| Diabetes Mellitus | 32 (16%) | 56 (19%) | 0.318 |

| Hypertension | 78 (39%) | 94 (33%) | 0.159 |

| Coronary Arterial Diseases | 23 (11%) | 36 (12%) | 0.723 |

| Other Diseases | 42 (21%) | 53 (18%) | 0.493 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) [Median (IQR)] | 26 (5) | 27 (5) | 0.005 |

| ASA Score | 0.108 | ||

| ASA 1 | 57 (28%) | 105 (36%) | |

| ASA 2 | 117 (58%) | 156 (54%) | |

| ASA 3 | 27 (14%) | 27 (10%) | |

| Neutrophil (mL) [Median (IQR)] | 4.6 (IQR: 3) | 4.6 (IQR: 2.7) | 0.962 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) [Median (IQR)] | 10.5 (IQR: 2.7) | 12.4 (IQR: 2.8) | <0.001 |

| Albumin (g/dL) [Median (IQR)] | 3.7 (IQR: 0.5) | 4.2 (IQR: 0.4) | <0.001 |

| Lymphocyte (mL) [Median (IQR)] | 1.3 (IQR: 0.5) | 2 (IQR: 0.9) | <0.001 |

| Platelet (cells ×109 L) [Median (IQR)] | 276 (IQR: 126) | 269 (IQR: 107) | 0.375 |

| Carcinoembryonic Antigen [Median (IQR)] | 7 (56) | 13 (73) | 0.406 |

| Cancer Antigen 19-9 [Median (IQR)] | 14 (76) | 21 (86) | 0.111 |

| N: 489 | PNI < 47.5 (N: 201) | PNI > 47.5 (N: 288) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor Localization | 0.985 | ||

| Right Colon | 63 (31%) | 97 (34%) | |

| Transverse Colon | 22 (11%) | 31 (11%) | |

| Left Colon | 55 (27%) | 78 (27%) | |

| Rectum | 54 (27%) | 72 (25%) | |

| FAP */Synchrone | 7 (4%) | 10 (3%) | |

| Operation | 0.552 | ||

| Right Hemicolectomy | 78 (39%) | 121 (42%) | |

| Left Hemicolectomy | 22 (11%) | 23 (8%) | |

| Anterior Resection | 36 (18%) | 45 (16%) | |

| Low Anterior Resection | 41 (20%) | 80 (28%) | |

| Abdominoperineal Resection | 16 (8%) | 7 (2%) | |

| Total Colectomy | 8 (4%) | 12 (4%) | |

| Operation Time (minute) [Median (IQR)] | 120 (60) | 120 (60) | 0.993 |

| Syncrone Metastasectomy | 23 (11%) | 32 (11%) | 0.494 |

| Syncrone Colon Tumor | 6 (3%) | 8 (3%) | 0.892 |

| Complications (CD ≥ Grade 3) | 17 (8%) | 17 (6%) | 0.342 |

| Hospital Stay (Days) [Median (IQR)] | 5 (2) | 5 (2) | 0.800 |

| Hospital Mortality | 8 (4%) | 3 (1%) | 0.031 |

| Pathological Stage | 0.418 | ||

| Stage I | 16 (8%) | 36 (12%) | |

| Stage II | 83 (41%) | 119 (41%) | |

| Stage III | 74 (37%) | 98 (34%) | |

| Stage IV | 28 (14%) | 35 (12%) | |

| Perineural Invasion | 70 (35%) | 87 (30%) | 0.282 |

| Lymphovascular Invasion | 131 (65%) | 193 (67%) | 0.672 |

| Tumor Diameter (mm) [Median (IQR)] | 50 (30) | 42 (30) | <0.001 |

| Adjuvant Chemotherapy | 130 (65%) | 214 (73%) | 0.042 |

| Adjuvant Radiotherapy | 24 (12%) | 35 (12%) | 0.487 |

| Harvested Lymph Nodes [Median (IQR)] | 19 (13) | 17 (10) | 0.459 |

| Tumor Positive Lympph Nodes (mean ± SD) | 1.6 (±2.7) | 1.4 (±2.9) | 0.904 |

| N: 489 | HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.821 | 0.572–1.179 | 0.286 | |||

| Age | 1.018 | 1.002–1.034 | 0.023 | 1.019 | 1.003–1.036 | 0.024 |

| Comorbid Diseases | 1.326 | 1.125–2.625 | 0.125 | |||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 0.995 | 0.920–1.077 | 0.906 | |||

| Tumor Localization (Colon vs. Rectum) | 1.114 | 0.724–1.716 | 0.623 | |||

| ASA Score | 0.638 | 0.383–1.063 | 0.084 | |||

| Stage (1–2 vs. 3–4) | 1.654 | 1.366–2.003 | <0.001 | 1.555 | 1.120–2.157 | 0.008 |

| Tumor Positive Lymph Nodes (N0 vs. N+) | 0.434 | 0.302–0.623 | <0.001 | 1.082 | 0.585–2001 | 0.803 |

| Tumor Diameter | 1.006 | 0.999–1014 | 0.101 | |||

| Perineural Invasion | 0.456 | 0.320–0.650 | <0.001 | 0.653 | 0.443–0.962 | 0.031 |

| Lymphovascular Invasion | 0.444 | 0.286–0.689 | <0.001 | 0.701 | 0.429–1.145 | 0.156 |

| Adjuvant Chemotherapy | 1.040 | 0.697–1.550 | 0.848 | |||

| Adjuvant Radiotherapy | 0.959 | 0.538–1.708 | 0.886 | |||

| PNI (<47.5) | 0.556 | 0.390–0.792 | <0.001 | 0.640 | 0.445–0.922 | 0.016 |

| N: 489 | HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.754 | 0.418–1.1359 | 0.348 | |||

| Age | 0.991 | 0.968–1.015 | 0.466 | |||

| Comorbid Diseases | 1.3216 | 1.025–1.912 | 0.332 | |||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 0.999 | 0.878–1.137 | 0.988 | |||

| Tumor Localization (Colon vs. Rectum) | 0.440 | 0.245–0.791 | 0.006 | 0.448 | 0.249–0.806 | 0.007 |

| ASA Score | 1.773 | 0.519–6.058 | 0.361 | |||

| Stage (1–2 vs. 3–4) | 1.309 | 0.981–1.746 | 0.067 | |||

| Tumor Positive Lymph Nodes (N0 vs. N+) | 0.640 | 0.361–1.135 | 0.127 | |||

| Tumor Diameter | 1.005 | 0.993–1017 | 0.383 | |||

| Perineural Invasion | 0.526 | 0.295–0.939 | 0.030 | 0.553 | 0.309–0.989 | 0.046 |

| Lymphovascular Invasion | 1.404 | 0.790–1.404 | 0.248 | |||

| Adjuvant Chemotherapy | 1.051 | 0.555–1.993 | 0.878 | |||

| Adjuvant Radiotherapy | 1.187 | 0.425–3.318 | 0.744 | |||

| PNI (<47.5) | 0.532 | 0.300–0.944 | 0.031 | 0.570 | 0.320–0.916 | 0.037 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Namdaroğlu, O.B.; Esmer, A.C.; Yazici, H.; Yakan, S. Prognostic Value of the Preoperative Prognostic Nutritional Index in Predicting Survival Outcomes After Curative Surgery for Colorectal Cancer. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3137. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233137

Namdaroğlu OB, Esmer AC, Yazici H, Yakan S. Prognostic Value of the Preoperative Prognostic Nutritional Index in Predicting Survival Outcomes After Curative Surgery for Colorectal Cancer. Healthcare. 2025; 13(23):3137. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233137

Chicago/Turabian StyleNamdaroğlu, Ozan Barış, Ahmet Cem Esmer, Hilmi Yazici, and Savaş Yakan. 2025. "Prognostic Value of the Preoperative Prognostic Nutritional Index in Predicting Survival Outcomes After Curative Surgery for Colorectal Cancer" Healthcare 13, no. 23: 3137. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233137

APA StyleNamdaroğlu, O. B., Esmer, A. C., Yazici, H., & Yakan, S. (2025). Prognostic Value of the Preoperative Prognostic Nutritional Index in Predicting Survival Outcomes After Curative Surgery for Colorectal Cancer. Healthcare, 13(23), 3137. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233137