Therapeutic Benefits of Robotics and Exoskeletons for Gait and Postural Balance Among Children and Adolescents with Cerebral Palsy: An Overview of Systematic Reviews

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

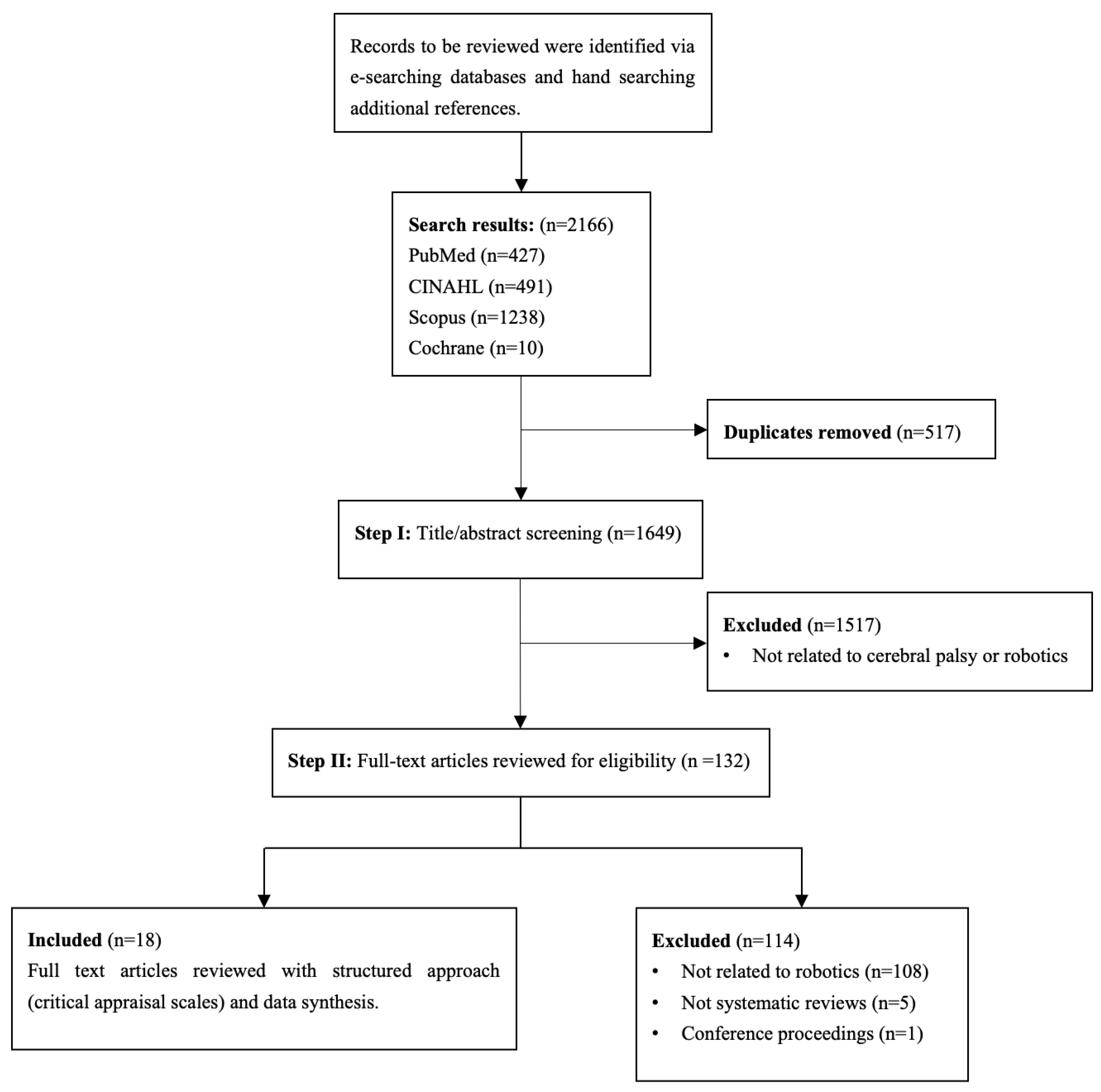

2.2. Literature Search

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

2.4. Assessment of Methodological Quality of Included Studies

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Included Studies

3.2. Quality of Systematic Reviews

3.3. Effectiveness of Robot-Assisted Gait Training (RAGT)

3.4. Impact of Robotic Exoskeletons on Mobility in CP

3.5. Comparing RAGT and Traditional Therapy

4. Discussion

4.1. Functional and Design Considerations of Robotic and Exoskeleton Systems

4.2. Methodological and Technical Gaps

4.3. Limitations and Uncertainties in RAGT and Exoskeleton Research

4.4. Clinical Implications

4.4.1. Children with Mild to Moderate Impairment (GMFCS II–III)

4.4.2. Children with Severe Motor Impairment (GMFCS IV–V)

4.5. Recommendations for Future Research

5. Study Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rosenbaum, P.; Paneth, N.; Leviton, A.; Goldstein, M.; Bax, M.; Damiano, D.; Dan, B.; Jacobsson, B. A report: The definition and classification of cerebral palsy April 2006. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. Suppl. 2007, 109, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, C.L.; Malouin, F. Cerebral palsy: Definition, assessment and rehabilitation. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 111, pp. 183–195. [Google Scholar]

- Sadowska, M.; Sarecka-Hujar, B.; Kopyta, I. Cerebral palsy: Current opinions on definition, epidemiology, risk factors, classification and treatment options. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2020, 16, 1505–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vova, J.A.; Eggebrecht, E.M. Utilizing functional electrical stimulation and exoskeletons in pediatrics: A closer look at their roles in gait and functional changes in cerebral palsy. Curr. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Rep. 2019, 7, 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, I.; Pinto, S.M.; das Virgens Chagas, D.; Dos Santos, J.L.P.; de Sousa Oliveira, T.; Batista, L.A. Robotic gait training for individuals with cerebral palsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2017, 98, 2332–2344. [Google Scholar]

- Brandenburg, J.E.; Fogarty, M.J.; Sieck, G.C. A critical evaluation of current concepts in cerebral palsy. Physiology 2019, 34, 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llamas-Ramos, R.; Sánchez-González, J.L.; Llamas-Ramos, I. Robotic systems for the physiotherapy treatment of children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, M.; Everaert, L.; Brown, M.; Muraru, L.; Hatzidimitriadou, E.; Desloovere, K. Effectiveness of robotic exoskeletons for improving gait in children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Gait Posture 2022, 98, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olmos-Gómez, R.; Gómez-Conesa, A.; Calvo-Muñoz, I.; López-López, J.A. Effects of robotic-assisted gait training in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy: A network meta-analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palisano, R.J.; Chiarello, L.A.; Orlin, M.; Oeffinger, D.; Polansky, M.; Maggs, J.; Bagley, A.; Gorton, G.; The Children’s Activity and Participation Group. Determinants of intensity of participation in leisure and recreational activities by children with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2011, 53, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Reid, S.M.; Carlin, J.B.; Reddihough, D.S. Using the Gross Motor Function Classification System to describe patterns of motor severity in cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2011, 53, 1007–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Cerebral Palsy Register (ACPR) Group. Report of the Australian Cerebral Palsy Register, Birth Years 1995–2012, November 2018; Australian Cerebral Palsy Register: Camperdown, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D.C.; Damiano, D.L.; Abel, M.F. The evolution of gait in childhood and adolescent cerebral palsy. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 1997, 17, 392–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, A.; Brien, M.; Plourde, J.; Wood, E.; Rosenbaum, P.; McLean, J. Stability of the Gross Motor Function Classification System in adults with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2007, 49, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannotti, M.; Gorton, G.E.; Nahorniak, M.T.; Gagnaire, N.; Fil, A.; Hogue, J.; Julewicz, J.; Hersh, E.; Marchion, V.; Masso, P.D. Changes in gait velocity, mean knee flexion in stance, body mass index, and popliteal angle with age in ambulatory children with cerebral palsy. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2008, 28, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maanum, G.; Jahnsen, R.; Frøslie, K.F.; Larsen, K.L.; Keller, A. Walking ability and predictors of performance on the 6-minute walk test in adults with spastic cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2010, 52, e126–e132. [Google Scholar]

- Bottos, M.; Feliciangeli, A.; Sciuto, L.; Gericke, C.; Vianello, A. Functional status of adults with cerebral palsy and implications for treatment of children. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2001, 43, 516–528. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Day, S.M.; Wu, Y.W.; Strauss, D.J.; Shavelle, R.M.; Reynolds, R.J. Change in ambulatory ability of adolescents and young adults with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2007, 49, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novak, I.; Mcintyre, S.; Morgan, C.; Campbell, L.; Dark, L.; Morton, N.; Stumbles, E.; Wilson, S.A.; Goldsmith, S. A systematic review of interventions for children with cerebral palsy: State of the evidence. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2013, 55, 885–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C. Comprehensive Physiotherapy Approaches for Children With Cerebral Palsy: Overview and Contemporary Trends. Phys. Ther. Korea 2023, 30, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunge, L.R.; Davidson, A.J.; Helmore, B.R.; Mavrandonis, A.D.; Page, T.D.; Schuster-Bayly, T.R.; Kumar, S. Effectiveness of powered exoskeleton use on gait in individuals with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, G.; Cai, X.; Xu, K.; Tian, H.; Meng, Q.; Ossowski, Z.; Liang, J. Which gait training intervention can most effectively improve gait ability in patients with cerebral palsy? A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Front. Neurol. 2023, 13, 1005485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volpini, M.; Aquino, M.; Holanda, A.C.; Emygdio, E.; Polese, J. Clinical effects of assisted robotic gait training in walking distance, speed, and functionality are maintained over the long term in individuals with cerebral palsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Disabil. Rehabil. 2022, 44, 5418–5428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Li, C. Systematic review and network meta-analysis of robot-assisted gait training on lower limb function in patients with cerebral palsy. Neurol. Sci. 2023, 44, 3863–3875. [Google Scholar]

- Inoue, Y.; Kuroda, Y.; Yamanoi, Y.; Yabuki, Y.; Yokoi, H. Development of wrist separated exoskeleton socket of myoelectric prosthesis hand for symbrachydactyly. Cyborg Bionic Syst. 2024, 5, 0141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, D.; Zhao, S.; Yu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Ruan, L.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, Q. Level-Ground and Stair Adaptation for Hip Exoskeletons Based on Continuous Locomotion Mode Perception. Cyborg Bionic Syst. 2025, 6, 0248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shea, B.J.; Grimshaw, J.M.; Wells, G.A.; Boers, M.; Andersson, N.; Hamel, C.; Porter, A.C.; Tugwell, P.; Moher, D.; Bouter, L.M. Development of AMSTAR: A measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2007, 7, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Shea, B.J.; Bouter, L.M.; Peterson, J.; Boers, M.; Andersson, N.; Ortiz, Z.; Ramsay, T.; Bai, A.; Shukla, V.K.; Grimshaw, J.M. External validation of a measurement tool to assess systematic reviews (AMSTAR). PLoS ONE 2007, 2, e1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balshem, H.; Helfand, M.; Schünemann, H.J.; Oxman, A.D.; Kunz, R.; Brozek, J.; Vist, G.E.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Meerpohl, J.; Norris, S.; et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 401–406. [Google Scholar]

- Alotaibi, A.; Ibrahim, A.; Ahmed, R.; Abualait, T. Effectiveness of Partial Body Weight-Supported Treadmill Training on Various Outcomes in Different Contexts among Children and Adolescents with Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Children 2023, 11, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonanno, M.; Militi, A.; La Fauci Belponer, F.; De Luca, R.; Leonetti, D.; Quartarone, A.; Ciancarelli, I.; Morone, G.; Calabro, R.S. Rehabilitation of Gait and Balance in Cerebral Palsy: A scoping review on the Use of Robotics with Biomechanical Implications. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, H.-C.; Ada, L.; Bania, T.A. Mechanically assisted walking training for walking, participation, and quality of life in children with cerebral palsy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 11, CD013114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, B.C.; Remec, N.M.; Lerner, Z.F. Is robotic gait training effective for individuals with cerebral palsy? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin. Rehabil. 2022, 36, 873–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortes-Perez, I.; Gonzalez-Gonzalez, N.; Peinado-Rubia, A.B.; Nieto-Escamez, F.A.; Obrero-Gaitan, E.; Garcia-Lopez, H. Efficacy of robot-assisted gait therapy compared to conventional therapy or treadmill training in children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Sensors 2022, 22, 9910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumplido, C.; Delgado, E.; Ramos, J.; Puyuelo, G.; Garcés, E.; Destarac, M.A.; Plaza, A.; Hernández, M.; Gutiérrez, A.; Garcia, E. Gait-assisted exoskeletons for children with cerebral palsy or spinal muscular atrophy: A systematic review. NeuroRehabilitation 2021, 49, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefmann, S.; Russo, R.; Hillier, S. The effectiveness of robotic-assisted gait training for paediatric gait disorders: Systematic review. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2017, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Valè, N.; Gandolfi, M.; Vignoli, L.; Botticelli, A.; Posteraro, F.; Morone, G.; Dell’Orco, A.; Dimitrova, E.; Gervasoni, E.; Goffredo, M.; et al. Electromechanical and robotic devices for gait and balance rehabilitation of children with neurological disability: A systematic review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 12061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezer, M.; Gresits, O.; Engh, M.A.; Szabó, L.; Molnar, Z.; Hegyi, P.; Terebessy, T. Evidence for gait improvement with robotic-assisted gait training of children with cerebral palsy remains uncertain. Gait Posture 2024, 107, 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Perpetuini, D.; Russo, E.F.; Cardone, D.; Palmieri, R.; Di Cesare, M.G.; Tritto, M.; Pellegrino, R.; Calabrò, R.S.; Filoni, S.; Merla, A. An fNIRS Based Assessment of Cortical Plasticity in Children with Cerebral Palsy Undergoing Robotic-Assisted Gait Training. In Proceedings of the International Conference on e-Health and Bioengineering, Bucharest, Romania, 9–10 November 2023; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 566–573. [Google Scholar]

- Damiano, D.L.; DeJong, S.L. A systematic review of the effectiveness of treadmill training and body weight support in pediatric rehabilitation. J. Neurol. Phys. Ther. 2009, 33, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paleg, G.; Livingstone, R. Outcomes of gait trainer use in home and school settings for children with motor impairments: A systematic review. Clin. Rehabil. 2015, 29, 1077–1091. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, D.L.; Murguialday, A.R.; Birbaumer, N.; Hoffmann, U.; Luft, A. Neurophysiology of Robot-Mediated Training and Therapy: A Perspective for Future Use in Clinical Populations. Front. Neurol. 2013, 4, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Vidal, J.L.; Bhagat, N.A.; Brantley, J.; Cruz-Garza, J.G.; He, Y.; Manley, Q.; Nakagome, S.; Nathan, K.; Tan, S.H.; Zhu, F.; et al. Powered exoskeletons for bipedal locomotion after spinal cord injury. J. Neural Eng. 2016, 13, 031001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandolfi, M.; Valè, N.; Posteraro, F.; Morone, G.; Dell’orco, A.; Botticelli, A.; Dimitrova, E.; Gervasoni, E.; Goffredo, M.; Zenzeri, J.; et al. State of the art and challenges for the classification of studies on electromechanical and robotic devices in neurorehabilitation: A scoping review. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2021, 57, 831–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerner, Z.F.; Gasparri, G.M.; Bair, M.O.; Lawson, J.L.; Luque, J.; Harvey, T.A.; Lerner, A.T. An Untethered Ankle Exoskeleton Improves Walking Economy in a Pilot Study of Individuals With Cerebral Palsy. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2018, 26, 1985–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, S.; Colazza, A.; Petrarca, M.; Castelli, E.; Cappa, P.; Krebs, H.I. Feasibility study of a wearable exoskeleton for children: Is the gait altered by adding masses on lower limbs? PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, Z.F.; Damiano, D.L.; Park, H.S.; Gravunder, A.J.; Bulea, T.C. A Robotic Exoskeleton for Treatment of Crouch Gait in Children With Cerebral Palsy: Design and Initial Application. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2017, 25, 650–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerner, Z.F.; Harvey, T.A.; Lawson, J.L. A Battery-Powered Ankle Exoskeleton Improves Gait Mechanics in a Feasibility Study of Individuals with Cerebral Palsy. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 47, 1345–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Orekhov, G.; Lerner, Z.F. Adaptive ankle exoskeleton gait training demonstrates acute neuromuscular and spatiotemporal benefits for individuals with cerebral palsy: A pilot study. Gait Posture 2022, 95, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Hochstein, J.; Kim, C.; Tucker, L.; Hammel, L.E.; Damiano, D.L.; Bulea, T.C. A Pediatric Knee Exoskeleton With Real-Time Adaptive Control for Overground Walking in Ambulatory Individuals With Cerebral Palsy. Front. Robot. AI 2021, 8, 702137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, Z.F.; Damiano, D.L.; Bulea, T.C. A lower-extremity exoskeleton improves knee extension in children with crouch gait from cerebral palsy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9, eaam9145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, Z.F.; Damiano, D.L.; Bulea, T.C. The Effects of Exoskeleton Assisted Knee Extension on Lower-Extremity Gait Kinematics, Kinetics, and Muscle Activity in Children with Cerebral Palsy. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell Esposito, E.; Schmidtbauer, K.A.; Wilken, J.M. Experimental comparisons of passive and powered ankle-foot orthoses in individuals with limb reconstruction. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2018, 15, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.J. Cerebral palsy update-Focusing on the treatments and interventions. Hanyang Med. Rev. 2016, 36, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

| Section and Topic | Item # | Checklist Item | Location Where Item Is Reported |

|---|---|---|---|

| Title | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review. | Title |

| Abstract | |||

| Abstract | 2 | See the PRISMA 2020 for Abstracts checklist. | Abstract |

| Introduction | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of existing knowledge. | Lines 101–121 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the objective(s) or question(s) the review addresses. | Lines 122–128 |

| Methods | |||

| Eligibility criteria | 5 | Specify the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review and how studies were grouped for the syntheses. | Lines 149–154 |

| Information sources | 6 | Specify all databases, registers, websites, organisations, reference lists and other sources searched or consulted to identify studies. Specify the date when each source was last searched or consulted. | Lines 134–142 |

| Search strategy | 7 | Present the full search strategies for all databases, registers and websites, including any filters and limits used. | Lines 134–142 |

| Selection process | 8 | Specify the methods used to decide whether a study met the inclusion criteria of the review, including how many reviewers screened each record and each report retrieved, whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | Lines 144–153 |

| Data collection process | 9 | Specify the methods used to collect data from reports, including how many reviewers collected data from each report, whether they worked independently, any processes for obtaining or confirming data from study investigators, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | Lines 155–159 |

| Data items | 10a | List and define all outcomes for which data were sought. Specify whether all results that were compatible with each outcome domain in each study were sought (e.g., for all measures, time points, analyses), and if not, the methods used to decide which results to collect. | Lines 155–159 |

| 10b | List and define all other variables for which data were sought (e.g., participant and intervention characteristics, funding sources). Describe any assumptions made about any missing or unclear information. | Lines 155–159 | |

| Study risk of bias assessment | 11 | Specify the methods used to assess risk of bias in the included studies, including details of the tool(s) used, how many reviewers assessed each study and whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | Lines 161–171 |

| Effect measures | 12 | Specify for each outcome the effect measure(s) (e.g., risk ratio, mean difference) used in the synthesis or presentation of results. | N/A |

| Synthesis methods | 13a | Describe the processes used to decide which studies were eligible for each synthesis (e.g., tabulating the study intervention characteristics and comparing against the planned groups for each synthesis (item #5)). | N/A |

| 13b | Describe any methods required to prepare the data for presentation or synthesis, such as handling of missing summary statistics, or data conversions. | N/A | |

| 13c | Describe any methods used to tabulate or visually display results of individual studies and syntheses. | Table 1 and Table 2 | |

| 13d | Describe any methods used to synthesize results and provide a rationale for the choice(s). If meta-analysis was performed, describe the model(s), method(s) to identify the presence and extent of statistical heterogeneity, and software package(s) used. | Table 1 and Table 2 | |

| 13e | Describe any methods used to explore possible causes of heterogeneity among study results (e.g., subgroup analysis, meta-regression). | N/A | |

| 13f | Describe any sensitivity analyses conducted to assess robustness of the synthesized results. | N/A | |

| Reporting bias assessment | 14 | Describe any methods used to assess risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis (arising from reporting biases). | Table 2 |

| Certainty assessment | 15 | Describe any methods used to assess certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for an outcome. | N/A |

| Results | |||

| Study selection | 16a | Describe the results of the search and selection process, from the number of records identified in the search to the number of studies included in the review, ideally using a flow diagram. | Results: Lines 1–12 |

| 16b | Cite studies that might appear to meet the inclusion criteria, but which were excluded, and explain why they were excluded. | N/A | |

| Study characteristics | 17 | Cite each included study and present its characteristics. | Table 1 and Table 2 |

| Risk of bias in studies | 18 | Present assessments of risk of bias for each included study. | Table 2 |

| Results of individual studies | 19 | For all outcomes, present, for each study: (a) summary statistics for each group (where appropriate) and (b) an effect estimate and its precision (e.g., confidence/credible interval), ideally using structured tables or plots. | N/A |

| Results of syntheses | 20a | For each synthesis, briefly summarise the characteristics and risk of bias among contributing studies. | Table 2 |

| 20b | Present results of all statistical syntheses conducted. If meta-analysis was done, present for each the summary estimate and its precision (e.g., confidence/credible interval) and measures of statistical heterogeneity. If comparing groups, describe the direction of the effect. | N/A | |

| 20c | Present results of all investigations of possible causes of heterogeneity among study results. | Table 2 | |

| 20d | Present results of all sensitivity analyses conducted to assess the robustness of the synthesized results. | N/A | |

| Reporting biases | 21 | Present assessments of risk of bias due to missing results (arising from reporting biases) for each synthesis assessed. | N/A |

| Certainty of evidence | 22 | Present assessments of certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for each outcome assessed. | N/A |

| Discussion | |||

| Discussion | 23a | Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence. | Lines 166–174 |

| 23b | Discuss any limitations of the evidence included in the review. | Lines 256–271 | |

| 23c | Discuss any limitations of the review processes used. | Lines 256–271 | |

| 23d | Discuss implications of the results for practice, policy, and future research. | Lines 273–288 | |

| Other Information | |||

| Registration and protocol | 24a | Provide registration information for the review, including register name and registration number, or state that the review was not registered. | Lines 131–134 |

| 24b | Indicate where the review protocol can be accessed, or state that a protocol was not prepared. | Lines 131–134 | |

| 24c | Describe and explain any amendments to information provided at registration or in the protocol. | N/A | |

| Support | 25 | Describe sources of financial or non-financial support for the review, and the role of the funders or sponsors in the review. | Line 296 |

| Competing interests | 26 | Declare any competing interests of review authors. | Line 297 |

| Availability of data, code and other materials | 27 | Report which of the following are publicly available and where they can be found: template data collection forms; data extracted from included studies; data used for all analyses; analytic code; any other materials used in the review. | N/A |

| Author and Year | AMSTAR Criteria | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | Total Score | |

| Alotaibi et al., 2024 [31] | Y | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | High |

| Bonanno et al., 2023 [32] | Y | PY | N | PY | Y | N | PY | N | N | N | NMA | NMA | N | N | NMA | Y | Critically Low |

| Bunge et al., 2021 [21] | Y | PY | N | PY | Y | Y | PY | PY | N | N | NMA | NMA | N | Y | NMA | Y | Critically Low |

| Carvalho et al., 2017 [5] | Y | Y | N | PY | Y | Y | PY | PY | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | Low |

| Chiu et al., 2020 [33] | Y | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y | NMA | NMA | Y | Y | NMA | Y | Moderate |

| Conner et al., 2022 [34] | Y | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y | PY | PY | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | Critically Low |

| Cortés-Pérez et al., 2022 [35] | Y | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | High |

| Cumplido et al., 2021 [36] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | PY | PY | Y | N | NMA | NMA | Y | Y | NMA | Y | Moderate |

| Hunt et al., 2022 [8] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | PY | PY | Y | N | NMA | NMA | Y | N | NMA | Y | Moderate |

| Lefmann et al., 2017 [37] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | PY | PY | Y | N | NMA | NMA | Y | N | NMA | Y | Moderate |

| Llamas-Ramos et al., 2022 [7] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | PY | PY | Y | N | NMA | NMA | N | N | NMA | Y | Low |

| Olmos-Gómez et al., 2021 [9] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | PY | PY | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Low |

| Qian et al., 2023 [22] | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | PY | PY | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Moderate |

| Valè et al., 2021 [38] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | PY | PY | Y | N | NMA | NMA | Y | N | NMA | Y | Low |

| Vezér et al., 2024 [39] | Y | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y | PY | PY | PY | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | High |

| Volpini et al., 2022 [23] | Y | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y | PY | PY | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | High |

| Vova et al., 2019 [4] | Y | N | N | PY | N | N | PY | PY | N | N | NMA | NMA | N | N | NMA | Y | Critically Low |

| Wang et al., 2023 [24] | Y | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | High |

| Authors | Review Objective | Participants | No. of Included Studies | Robotics Included in the Review | Main Findings | GRADE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alotaibi et al., 2024 [31] | To review the scientific literature on the efficacy of PBWSTT on various outcome measures among children with CP in different settings. | 255 | 10 | PBWSTT | PBWSTT programs of 4–12 weeks produced consistent improvements in gait, gross motor function, stability and balance in children and adolescents with CP. PBWSTT proved feasible across settings (home, school). Evidence is sparse for longer programs (12–24 weeks) and long-term retention. | Moderate |

| Bonanno et al., 2023 [32] | To investigate the effects of robotic systems on improving gait and balance in children and adolescents with CP, with a focus on biomechanical implications. | Not specified | 18 | Lokomat, Alter-G, HBRS, RG, HWA, RAGT, InnPro and Exoskeleton | The review reports that robotic-assisted gait and trunk training (RAGT) and related devices (exoskeletons, Alter-G, HBRS) can improve postural control, balance, trunk activation, and gross motor function in children and adolescents with CP—especially those with mild–moderate impairments. Robotic approaches tend to better improve dynamic balance and gait symmetry than some spatiotemporal parameters. Combining robotics with VR may boost outcomes. However, heterogeneous devices, variable protocols, and limited participant detail make it hard to identify the single best approach. | Low |

| Bunge et al., 2021 [21] | To determine the effectiveness of utilizing powered lower limb exoskeletons on gait in individuals with CP. | 82 | 13 | HAL, CPW, LEE, WAKE, BLAE, and NFW | The evidence indicates beneficial changes in spatiotemporal gait outcomes after interventions, with 10 of 13 studies reporting higher gait velocity (5 reaching statistical significance). Findings on metabolic/energy cost are inconsistent—some studies report reductions while others find no change. Reported adverse events (skin irritation, fatigue) were few and transient. Major limitations are small pilot samples and considerable participant heterogeneity (notably across GMFCS levels), which reduce generalizability. | Moderate |

| Carvalho et al., 2017 [5] | To review the effects of robotic gait training practices in individuals with cerebral palsy. | 189 | 10 | GTI and Locomat | Review shows that robotic gait training modestly improves gait speed and endurance and yields small improvements in gross motor function. Higher training dose (≥4 sessions/week and ≥30 min/session) is associated with larger gains. However, small sample sizes, broad GMFCS ranges (I–IV), and inconsistent training parameters across studies weaken causal conclusions. | Low |

| Chiu et al., 2020 [33] | To assess the effects of mechanically assisted walking training compared to control for walking, participation, and quality of life in children with cerebral palsy 3 to 18 years of age. | 451 | 17 | RAGT | The reviews report limited-to-modest benefits from mechanically assisted walking interventions in children with CP. Body-weight-supported robotic training increased walking speed compared with no training but generally did not improve gross motor function or outperform overground walking. Study heterogeneity and sparse representation of GMFCS IV and children < 9 years limit confidence. | High |

| Conner et al., 2022 [34] | To determine if robotic gait training for individuals with CP is effective more than standard physical therapy care. | 188 | 8 | Lokomat, GTI and 3DCaLT | The review found limited additional benefit of robotic gait devices versus dose-matched conventional therapy for walking speed and gross motor function, likely because many devices are primarily assistive and do not sufficiently engage active neuromuscular control. Resistive robotic training produced better locomotor gains. VR and biofeedback appear to enhance outcomes when paired with robotics. Interpretation is constrained by small samples, diverse protocols, high CP heterogeneity, and the review’s focus on spastic diplegia/triplegia. | Low |

| Cortés-Pérez et al., 2022 [35] | To review previous studies related to RAGT and compare its efficacy against CT or TT for improving gait ability, gross motor function and functional independence in children with CP. | 413 | 15 | Lokomat, walkbot-k, EksoGT, RT600, GTI, 3DCaLT, InnPro | The review indicates RAGT yields superior post-intervention gains in gait speed, walking distance and GMFM walking/running/jumping compared with dose-matched conventional therapy. Comparisons with treadmill training are generally inconclusive, and no consistent benefits were seen for step length or when RAGT was added to conventional therapy. Confidence is tempered by small study counts, risk of publication bias, and limited long-term follow-up. | Low |

| Cumplido et al., 2021 [36] | To assess the safety and efficacy of robot-assisted interventions in rehabilitation programs for children with CP or SMA. | 742 | 21 | Locomat, CP walker, Walkbot-K, The Hybrid Assistive Limb, Robogait | The review reports that robotic-assisted gait training is generally well tolerated in pediatric CP populations and that gait exoskeletons (e.g., Lokomat) show promising gait improvements in some studies. However, results vary by protocol and participant characteristics, and confidence is limited by small sample sizes, short or absent follow-up, unclear randomization and control procedures, and narrow selection criteria that may have excluded relevant evidence. | Low |

| Hunt et al., 2022 [8] | To systematically review the literature investigating spatiotemporal, kinematic, kinetic, muscle activity and physiological parameters during exoskeleton-assisted walking in children with CP. | 25 | 13 | TKE, TAE, UTAE, WUAM, WUKAM, P.REX, UAE | The literature suggests lightweight exoskeletons can improve stance-phase knee/hip extension, enhance step length and other spatiotemporal gait measures, and sometimes lower walking energy cost in children with CP. TKE has repeatedly increased walking speed (primarily via longer stride length). UAE, TKE and P.REX show promise for crouch gait. Overall evidence is sparse, based on small studies with varied protocols, which makes direct comparison and generalization difficult. | Low |

| Lefmann et al., 2017 [37] | To identify and appraise the existing evidence for the effectiveness of RAGT for pediatric gait disorders, including modes of delivery and potential benefit. | 468 | 17 | Lokomat, GTI and CPW | The review finds no consistent benefit of RAGT versus conventional physiotherapy for gait function at group level (meta-analysis showed no significant difference). A minority of studies reported durable or endurance improvements (3 of 8 for endurance), but results are variable. Combining RAGT with VR often produced larger effects, suggesting increased engagement matters. Overall confidence is low because of small sample sizes, low methodological quality, high risk of bias, and heterogeneous RAGT protocols. | Moderate |

| Llamas-Ramos et al., 2022 [7] | To systematically review the available evidence on the effectiveness of robotic systems for the treatment of children with CP to improve their autonomy and quality of life. | 174 | 7 | Lokomat, InnPro, robogait, WKS | Review concluded that across studies, adding robotic devices to conventional therapy produced small improvements in gait, strength, balance and endurance, with some sustained effects reported for Innowalk Pro. The Lokomat (which was the most studied) brought only modest gains and did not clearly beat standard therapy. Importantly, robotics serve best as complements to usual care. Evidence is constrained by short follow-ups, low methodological quality, and small sample sizes, so larger, longer, rigorous trials are needed. | Moderate |

| Olmos-Gómez et al., 2021 [9] | To examine the efficacy of RAGT among children and adolescents with CP to improve both standing and walking, as well as the characteristics of the gait with respect to speed, endurance, and stride length. | 217 | 8 | Lokomat, 3DCaLT, InnPro, Gait trainer. | Although some individual studies hint that RAGT can help children and adolescents with CP, the pooled analyses show no clear superiority of RAGT (alone or combined with physiotherapy) compared with physiotherapy alone across examined gait outcomes. Reported effects are small. Major limits are small study counts, strict selection criteria causing clinical heterogeneity, variable devices/doses/protocols, and unclear/high risk of bias, all of which restrict clinical recommendations. | Low |

| Qian et al., 2023 [22] | To evaluate and compare the effects of different approaches of gait training on gait ability in people with CP. | 516 | 20 | PBWSTT and RAGT | The meta-analysis suggests BWSTT is most likely to improve gait speed, whereas robotic-assisted approaches (RAGT) are most likely to improve standing (GMFM-D) and walking/running/jumping (GMFM-E). Effect-ranking (SUCRA) favors different interventions for different outcomes, but sparse study counts and inconsistent reporting of total training duration, session frequency and exercise intensity weaken the certainty and practical applicability of these findings. | Low |

| Valè et al., 2021 [38] | To provide an overview of the existing literature on robots and electromechanical devices used for the rehabilitation of gait and balance among children with neurological disabilities. | 29 | 31 | Lokomat, Lokomat +FreeD, MOTOMED, HAL, Ekso GT, IRAP, InnPro, Trexo-Home, GTI, FORTIS-102, PediAnklebot, ATLAS Exoskeleton | The review finds robot-assisted therapy feasible and potentially beneficial for children and adolescents, with few reported adverse events. It highlights the need for pediatric-specific robotic designs and for clinicians to use task-oriented, individualized protocols to boost neuroplasticity and functional recovery. Consistent with prior work, pairing robotics with VR appears to enhance engagement and motor learning. Poor descriptions of devices and protocols remain a major limitation. | Low |

| Vezér et al., 2024 [39] | To examine the effect of RAGT on gait function and on temporospatial gait parameters in children with CP. | 318 | 13 | RAGT | The evidence for robotic-assisted gait training (RAGT) is mixed. While individual studies found gains in postural stability (GMFM-D), walking ability (GMFM-E), step length and gait velocity, pooled or controlled comparisons typically show no clear superiority of RAGT compared to dose-matched treadmill training or conventional therapy. Cadence and many other gait parameters usually remain unchanged. Major constraints are high heterogeneity, small sample sizes, risk of bias (often unblinded), variable training protocols, and lack of long-term follow-up. | Moderate |

| Volpini et al., 2022 [23] | To evaluate the short-term and long-term effects of RAGT on walking distance, gait speed, and functionality in individuals with CP. | 77 | 7 | RAGT | The review reports that robotic-assisted gait training yields large clinical improvements in gait speed and gross motor function (GMFM-D/E) and significantly increases walking endurance (6 MWT), with many gains persisting long term. However, statistical analyses sometimes fail to show significance (reflecting small samples and variability). Heterogeneous protocols, limited follow-up, and poor control of post-trial activities weaken conclusions. RAGT appears to be valuable as an adjunct but needs robust trials to confirm optimal dosing and durability. | High |

| Vova et al., 2019 [4] | To explore the efficacy of two modalities, FES and exoskeletons in gait training to improve motor function and improve gait efficiency in pediatric individuals with CP. | 208 | 14 | Lockomat, CPW, HAL, exoskeleton. | Across the reviewed studies, exoskeletons improved gait speed, endurance, gross motor function (GMFM D/E), hip/knee kinematics and reduced crouch gait. These effects were strongest when users were actively engaged and training included task variability. Functional Electrical Stimulation, both for ambulation and cycling, improved gait kinematics, ankle dorsiflexion strength, reduced spasticity and increased walking speed, balance and muscle activation. However, most studies had small samples, few controls, variable protocols and short follow-up, so larger standardized trials are needed. | Low |

| Wang et al., 2023 [24] | To evaluate the effectiveness of RAGT in improving lower extremity function in patients with CP and compare the efficacy between different robotic systems. | 654 | 14 | RAGT: LokoHelp, Lokomat, 3DCaLT, GTI | This review finds that robotic-assisted gait training produces meaningful gains in standing and walking function (GMFM D/E), postural balance (BBS) and walking endurance (6 MWT) compared with conventional rehab, with LokoHelp and Lokomat leading rankings and 3DCaLT showing little effect. Statistical improvements in gait speed were generally absent despite some clinically meaningful changes. Interpretation is constrained by small samples, lack of blinding, wide variability in age/CP severity, and inconsistent training frequency/duration. | Moderate |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alharbi, A.; Alhosaini, S.S.; Alrakebeh, S.S.; Aloraini, S.M. Therapeutic Benefits of Robotics and Exoskeletons for Gait and Postural Balance Among Children and Adolescents with Cerebral Palsy: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3120. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233120

Alharbi A, Alhosaini SS, Alrakebeh SS, Aloraini SM. Therapeutic Benefits of Robotics and Exoskeletons for Gait and Postural Balance Among Children and Adolescents with Cerebral Palsy: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. Healthcare. 2025; 13(23):3120. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233120

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlharbi, Amal, Shouq S. Alhosaini, Shahad S. Alrakebeh, and Saleh M. Aloraini. 2025. "Therapeutic Benefits of Robotics and Exoskeletons for Gait and Postural Balance Among Children and Adolescents with Cerebral Palsy: An Overview of Systematic Reviews" Healthcare 13, no. 23: 3120. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233120

APA StyleAlharbi, A., Alhosaini, S. S., Alrakebeh, S. S., & Aloraini, S. M. (2025). Therapeutic Benefits of Robotics and Exoskeletons for Gait and Postural Balance Among Children and Adolescents with Cerebral Palsy: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. Healthcare, 13(23), 3120. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233120