From Growth Mindsets to Life Satisfaction: Examining the Role of Cognitive Reappraisal and Stressful Life Events

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. A Framework for Linking Beliefs, Coping, and Well-Being

1.2. Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Implicit Theories of Thoughts, Emotion, and Behavior

2.2.2. Cognitive Reappraisal

2.2.3. Life Satisfaction

2.2.4. Stressful Life Events

2.2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptives and Correlations

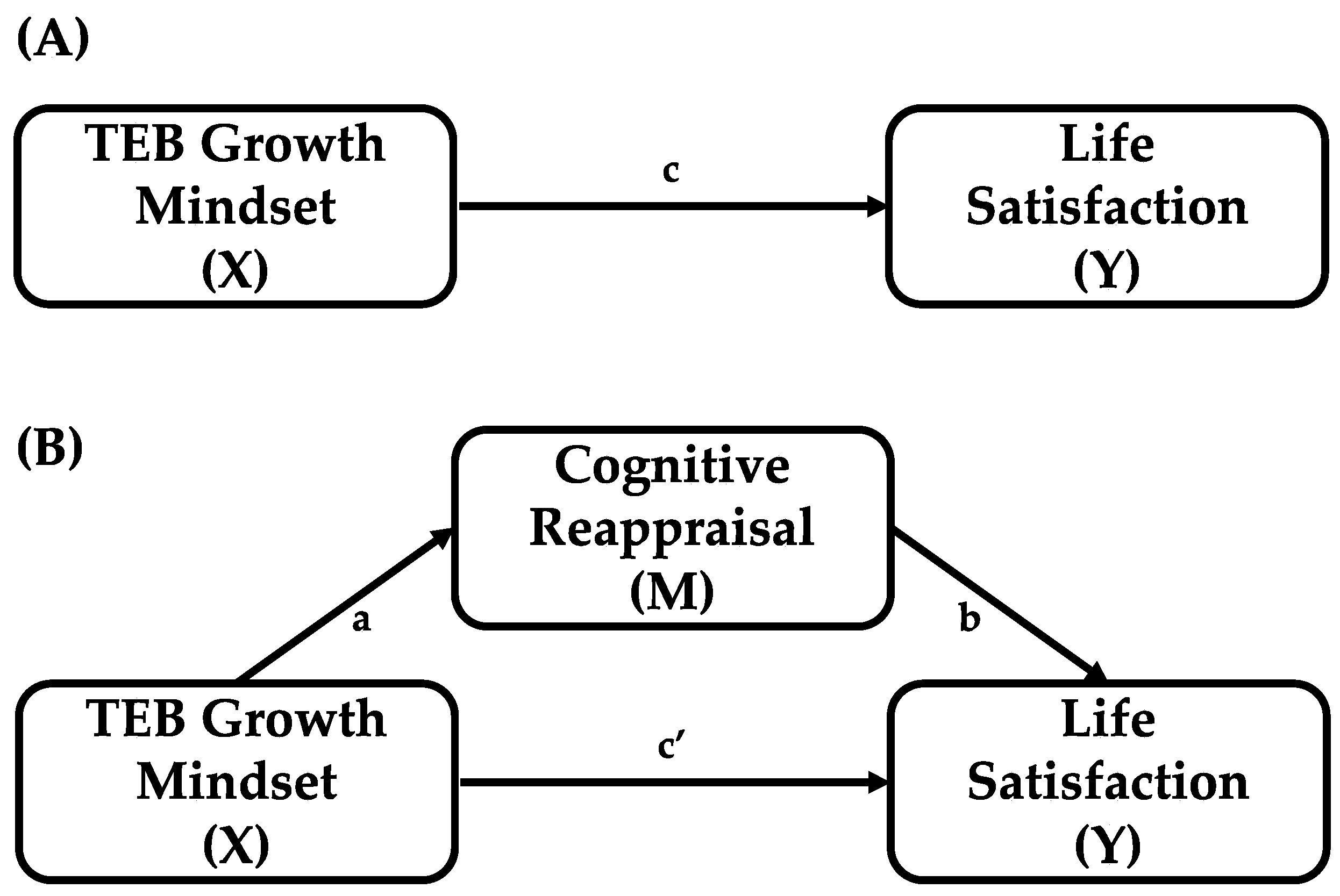

3.2. Mediation Model

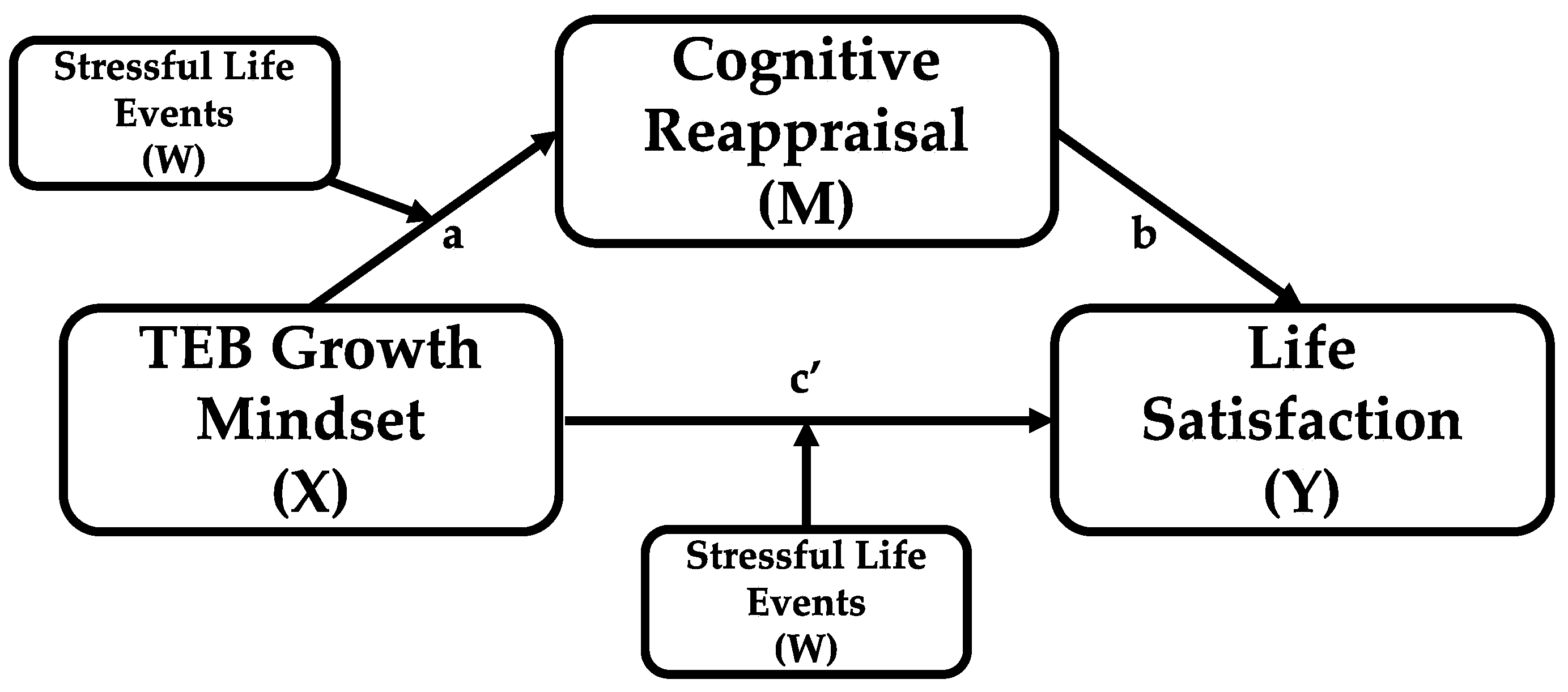

3.3. Moderated Mediation Model

3.4. Exploratory Moderation Analyses by Gender and Educational Grade

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.; Demler, O.; Jin, R.; Merikangas, K.R.; Walters, E.E. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapee, R.M.; Oar, E.L.; Johnco, C.J.; Forbes, M.K.; Fardouly, J.; Magson, N.R.; Richardson, C.E. Adolescent development and risk for the onset of social-emotional disorders: A review and conceptual model. Behav. Res. Ther. 2019, 123, 103501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca-Pedrero, E.; Díez-Gómez, A.; de la Barrera, U.; Sebastian-Enesco, C.; Ortuño-Sierra, J.; Montoya-Castilla, I.; Lucas-Molina, B.; Inchausti, F.; Pérez-Albéniz, A. Suicidal behaviour in adolescents: A network analysis. Span. J. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2024, 17, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbers, J.E.; Hayes, K.R.; Cutuli, J.J. Adaptive systems for student resilience in the context of COVID-19. Sch. Psychol. 2021, 36, 422–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S. Theory-Based Stress Measurement. Psychol. Inq. 1990, 1, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osher, D.; Cantor, P.; Berg, J.; Steyer, L.; Rose, T. Drivers of human development: How relationships and context shape learning and development. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2020, 24, 6–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, E.A.; Graham, J.P.; Brule, H.; Rickert, N.; Kindermann, T.A. “I Get Knocked down but I Get up Again”: Integrative frameworks for studying the development of motivational resilience in school. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2020, 44, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C.S.; Leggett, E.L. A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychol. Rev. 1988, 95, 256–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C.S. Mindset: The New Psychology of Success; Ballantine Books: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell, L.S.; Trzesniewski, K.H.; Dweck, C.S. Implicit theories of intelligence predict achievement across an adolescent transition: A longitudinal study and an intervention. Child Dev. 2007, 78, 246–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnette, J.L.; O’Boyle, E.H.; VanEpps, E.M.; Pollack, J.M.; Finkel, E.J. Mind-sets matter: A meta-analytic review of implicit theories and self-regulation. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 139, 655–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeager, D.S.; Trzesniewski, K.H.; Dweck, C.S. An implicit theories of personality intervention reduces adolescent aggression in response to victimization and exclusion. Child Dev. 2013, 84, 970–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnette, J.L.; Knouse, L.E.; Vavra, D.T.; O’Boyle, E.; Brooks, M.A. Growth mindsets and psychological distress: A meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 7, 101816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeager, D.S.; Dweck, C.S. What can be learned from growth mindset controversies? Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 1269–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamir, M.; John, O.P.; Srivastava, S.; Gross, J.J. Implicit theories of emotion: Affective and social outcomes across a major life transition. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 92, 731–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Castella, K.; Goldin, P.; Jazaieri, H.; Ziv, M.; Dweck, C.S.; Gross, J.J. Beliefs about emotion: Links to emotion regulation, well-being, and psychological distress. Basic Appl. Soc. Psych. 2013, 35, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneeland, E.T.; Dovidio, J.F.; Joormann, J.; Clark, M.S. Emotion malleability beliefs, emotion regulation, and psychopathology: Integrating affective and clinical science. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 45, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroder, H.S.; Dawood, S.; Yalch, M.M.; Donnellan, M.B.; Moser, J.S. The role of implicit theories in mental health symptoms, emotion regulation, and hypothetical treatment choices in college students. Cognit. Ther. Res. 2015, 39, 120–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, K.E.; Goodman, F.R.; Beltzer, M.L.; Daros, A.R.; Boukhechba, M.; Barnes, L.E.; Teachman, B.A. Emotion malleability beliefs and emotion experience and regulation in the daily lives of people with high trait social anxiety. Cognit. Ther. Res. 2020, 44, 1186–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, A.; Faria, L. Implicit theories of emotional intelligence, ability and trait-emotional intelligence and academic achievement. Psihol. Teme 2020, 29, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleider, J.L.; Weisz, J.R. Implicit theories relate to youth psychopathology, but how? A longitudinal test of two predictive models. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2016, 47, 603–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schleider, J.L.; Weisz, J.R. Mental health and implicit theories of thoughts, feelings, and behavior in early adolescents: Are girls at greater risk? J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 35, 130–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Paley, N.; Shi, D. Examining the validity and measurement invariance across gender and race of the Implicit Thoughts, Emotion, and Behavior Questionnaire. Sch. Psychol. 2022, 37, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, K.A.; Jiang, X. An examination of the moderating role of growth mindset in the relation between social stress and externalizing behaviors among adolescents. J. Adolesc. 2022, 94, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F. On the Self-Regulation of Behavior; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- De France, K.; Hollenstein, T. Implicit theories of emotion and mental health during adolescence: The mediating role of emotion regulation. Cogn. Emot. 2021, 35, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, B.Q.; Lwi, S.J.; Gentzler, A.L.; Hankin, B.; Mauss, I.B. The cost of believing emotions are uncontrollable: Youths’ beliefs about emotion predict emotion regulation and depressive symptoms. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2018, 147, 1170–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compas, B.E.; Jaser, S.S.; Bettis, A.H.; Watson, K.H.; Gruhn, M.A.; Dunbar, J.P.; Williams, E.; Thigpen, J.C. Coping, Emotion regulation, and psychopathology in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 939–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciniak, M.A.; Homan, S.; Zerban, M.; Schrade, G.; Yuen, K.S.L.; Kobylińska, D.; Wieser, M.J.; Walter, H.; Hermans, E.J.; Shanahan, L.; et al. Positive cognitive reappraisal flexibility is associated with lower levels of perceived stress. Behav. Res. Ther. 2024, 183, 104653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, J.P.; Crum, A.J.; Goyer, J.P.; Marotta, M.E.; Akinola, M. Optimizing stress responses with reappraisal and mindset interventions: An integrated model. Anxiety Stress Coping 2018, 31, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.W.Y.; Lee, A.N. Mindsets, emotion regulation, and student outcomes: Evidence from a sample of higher education students in Singapore. Curr. Psychol. 2025, 44, 4988–5002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, E.; Min, K.S.; Porter, M.; Kennett-Hensel, P.; Corey, C. Don’t stop believing: The role of growth mindset and emotion regulation in promoting student success and well-being. Mkt. Educ. Rev. 2025. advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Deng, Q.; Wu, L.; Ye, M. Unpacking stress perception responses to illegitimate tasks: The role of appraisals and performance-prove goal orientation. Curr. Psychol. 2025, 44, 17846–17858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deplancke, C.; Somerville, M.P.; Harrison, A.; Vuillier, L. It’s All about beliefs: Believing emotions are uncontrollable is linked to symptoms of anxiety and depression through cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 22004–22012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riepenhausen, A.; Wackerhagen, C.; Reppmann, Z.C.; Deter, H.-C.; Kalisch, R.; Veer, I.M.; Walter, H. Positive cognitive reappraisal in stress resilience, mental health, and well-being: A comprehensive systematic review. Emot. Rev. 2022, 14, 310–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braet, J.; Giletta, M.; Wante, L.; Van Beveren, M.; Verbeken, S.; Goossens, L.; Lomeo, B.; Anslot, E.; Braet, C. The relationship between perceived stress and depressive symptoms in adolescents during high stress: The moderating role of emotion regulation. J. Adolesc. 2022, 94, 1179–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grych, J.; Taylor, E.; Banyard, V.; Hamby, S. Applying the dual factor model of mental health to understanding protective factors in adolescence. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2020, 90, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huebner, E.S. Preliminary development and validation of a multidimensional life satisfaction scale for children. Psychol. Assess. 1994, 6, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, K.N.; Malecki, C.K. Academic grit scale: Psychometric properties and associations with achievement and life satisfaction. J. Sch. Psychol. 2019, 72, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C.S. Self-Theories: Their Role in Motivation, Personality, and Development; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck, C.S. Can personality be changed? The role of beliefs in personality and change. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 17, 391–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullone, E.; Taffe, J. The Emotion Regulation Questionnaire for Children and Adolescents (ERQ–CA): A psychometric evaluation. Psychol. Assess. 2012, 24, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J.; John, O.P. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, A.; Silva, E.; Tavares, D.; Freire, T. Portuguese validation of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire for Children and Adolescents (ERQ-CA): Relations with self-esteem and life satisfaction. Child. Indic. Res. 2015, 8, 605–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligson, J.L.; Huebner, E.S.; Valois, R.F. Preliminary validation of the Brief Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale (BMSLSS). Soc. Indic. Res. 2003, 61, 121–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zullig, K.J.; Huebner, E.S.; Gilman, R.; Patton, J.M.; Murray, K.A. validation of the Brief Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale among college students. Am. J. Health Behav. 2005, 29, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.H.; McCutcheon, S.M. Assessing life stress in older children and adolescents: Preliminary findings with the Life Events Checklist. Stress Anxiety 1980, 7, 111–125. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, M.D.; Jiang, X. School-related social support as a buffer to stressors in the development of adolescent life satisfaction. J. Appl. Sch. Psychol. 2022, 38, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, A.H.; Johnson, J.H. Note on reliability of the Life Events Checklist. Psychol. Rep. 1982, 50 (Suppl. S3), 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggal, S.; Malkoff-Schwartz, S.; Birmaher, B.; Anderson, B.P.; Matty, M.K.; Houck, P.R.; Bailey-Orr, M.; Williamson, D.E.; Frank, E. Assessment of life stress in adolescents: Self-report versus interview methods. J. Am Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2000, 39, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiet, Q.; Bird, H.; Hoven, C.; Moore, R.; Wu, P.; Wicks, J.; Jensen, P.; Goodman, S.; Cohen, P. Relationship between specific adverse life events and psychiatric disorders. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2001, 29, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meade, J.A.; Lumley, M.A.; Casey, R.J. Stress, emotional skill, and illness in children: The importance of distinguishing between children’s and parents’ reports of illness. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2001, 42, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Smith, I.C.; Ginsburg, G. Do self-processes and parenting mediate the effects of anxious parents’ psychopathology on youth depression and suicidality? Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2024, 56, 1433–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yuan, M.; Zeng, Y.; Xie, Y.; Xu, Y.; Liao, D.; Chen, Y.; Chen, M.; Qu, Y.; Hu, Y.; et al. Cohort profile: The China Severe Trauma Cohort (CSTC). J. Epidemiol. 2024, 34, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevan Jones, R.; Merry, S.; Stallard, P.; Randell, E.; Weavers, B.; Gray, A.; Hindle, E.; Gavigan, M.; Clarkstone, S.; Williams-Thomas, R.; et al. Further development and feasibility randomised controlled trial of a digital programme for adolescent depression, MoodHwb: Study protocol. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e070369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Little, T.D. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Blevins, C.A.; Weathers, F.W.; Davis, M.T.; Witte, T.K.; Domino, J.L. The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. J. Trauma Stress 2015, 28, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linacre, J.M. Optimizing rating scale category effectiveness. J. Appl. Meas. 2002, 3, 85–106. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P.E.; Bolger, N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 422–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antaramian, S.P.; Huebner, E.S.; Hills, K.J.; Valois, R.F. A dual-factor model of mental health: Toward a more comprehensive understanding of youth functioning. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2010, 80, 462–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, D.; Wang, J. Dual-Factor Model of Mental Health: Surpass the Traditional Mental Health Model. Psychology 2011, 2, 767–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grych, J.H.; Hamby, S.; Banyard, V. The Resilience Portfolio Model: Understanding healthy adaptation in victims of violence. Psychol. Violence 2015, 5, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Fang, L.; Mueller, C.E. Growth mindset: An umbrella for protecting socially stressed adolescents’ life satisfaction. Sch. Psychol. 2025, 40, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerville, L.H. The teenage brain: Sensitivity to social evaluation. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 22, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinberg, L. Cognitive and affective development in adolescence. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2005, 9, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steare, T.; Gutiérrez Muñoz, C.; Sullivan, A.; Lewis, G. The association between academic pressure and adolescent mental health problems: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 339, 302–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Category | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Grade Level | 9th Grade | 74 (12.0%) |

| 10th Grade | 115 (18.7%) | |

| 11th Grade | 147 (23.9%) | |

| 12th Grade | 284 (45.4%) | |

| School Setting | Suburban | 319 (51.5%) |

| Urban | 205 (33%) | |

| Rural | 96 (15.5%) | |

| Gender | Female | 307 (49.5%) |

| Male | 270 (43.5%) | |

| Gender-Nonconforming/Variant | 36 (5.8%) | |

| Not Disclosed | 7 (1.1%) | |

| Living Arrangements | Both Parents | 406 (65.5%) |

| Mother or Mother Figure | 162 (26.1%) | |

| Father or Father Figure | 23 (3.7%) | |

| Other Adults | 29 (4.7%) | |

| Racial Identity | White | 256 (41.3%) |

| Black | 120 (19.4%) | |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 119 (19.2%) | |

| Multiple Selections | 56 (9.0%) | |

| Asian | 40 (6.5%) | |

| Biracial or Multiracial | 22 (3.5%) | |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 6 (1.0%) | |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 1 (0.2%) | |

| Geographic Region | South | 223 (36.0%) |

| West | 167 (27.0%) | |

| Midwest | 118 (19.0%) | |

| Northeast | 112 (18.0%) |

| Variable | Mean (SD) | α | ω | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. ITEB | 4.10 (0.84) | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.44 ** | −0.07 | 0.43 ** |

| 2. Cognitive reappraisal | 3.38 (0.67) | 0.78 | 0.77 | - | −0.03 | 0.35 ** |

| 3. Stressful life events | 4.59 (2.85) | 0.68 | 0.65 | - | - | −0.26 ** |

| 4. Life satisfaction | 5.48 (1.25) | 0.82 | 0.82 | - | - | - |

| Group | n | ITEB M (SD) | Cognitive Reappraisal M (SD) | Life Satisfaction M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Girls (1) | 307 | 4.06 (0.83) | 3.33 (0.65) | 4.23 (1.06) |

| Boys (2) | 270 | 4.20 (0.79) | 3.47 (0.67) | 4.62 (1.16) |

| Grade | ||||

| 9th grade | 74 | 4.01 (0.94) | 3.30 (0.66) | 4.47 (1.24) |

| 10th grade | 115 | 4.01 (0.83) | 3.32 (0.67) | 4.36 (1.07) |

| 11th grade | 147 | 4.09 (0.85) | 3.39 (0.68) | 4.28 (1.23) |

| 12th grade | 284 | 4.16 (0.81) | 3.41 (0.66) | 4.43 (1.05) |

| B | SE | β | t | p | CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path a: ITEB → Cognitive Reappraisal | 0.35 | 0.44 | 0.03 | 12.25 | <0.001 | [0.29, 0.41] |

| Path b: Cognitive Reappraisal → Life Satisfaction | 0.34 | 0.07 | 0.20 | 5.15 | <0.001 | [0.21, 0.48] |

| Total Effect (path c): ITEB → Life Satisfaction | 0.57 | 0.05 | 0.43 | 11.70 | <0.001 | [0.47, 0.67] |

| Direct Effect (path c’): ITEB → Life Satisfaction | 0.45 | 0.05 | 0.34 | 8.52 | <0.001 | [0.35, 0.56] |

| Indirect Effect: ITEB → Cognitive Reappraisal → Life Satisfaction | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.09 | - | - | [0.07, 0.18] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Goran, R.F.; Jiang, X. From Growth Mindsets to Life Satisfaction: Examining the Role of Cognitive Reappraisal and Stressful Life Events. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2985. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222985

Goran RF, Jiang X. From Growth Mindsets to Life Satisfaction: Examining the Role of Cognitive Reappraisal and Stressful Life Events. Healthcare. 2025; 13(22):2985. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222985

Chicago/Turabian StyleGoran, Rahma F., and Xu Jiang. 2025. "From Growth Mindsets to Life Satisfaction: Examining the Role of Cognitive Reappraisal and Stressful Life Events" Healthcare 13, no. 22: 2985. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222985

APA StyleGoran, R. F., & Jiang, X. (2025). From Growth Mindsets to Life Satisfaction: Examining the Role of Cognitive Reappraisal and Stressful Life Events. Healthcare, 13(22), 2985. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222985