Experiences of People Living with a Kidney Transplant: A Phenomenological Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Participant Recruitment

2.2. Sample

2.3. Protocol

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Rigor and Trustworthiness

2.6. Ethical Consideration

3. Results

- The participants’ demographic characteristics consisted of 25 participants, who comprised 13 males and 12 females, aged between 28 and 77 (average 53.9 years). There are 5 participants with LDKT and 19 participants with DDKT. Most participants had complications (Table 1).

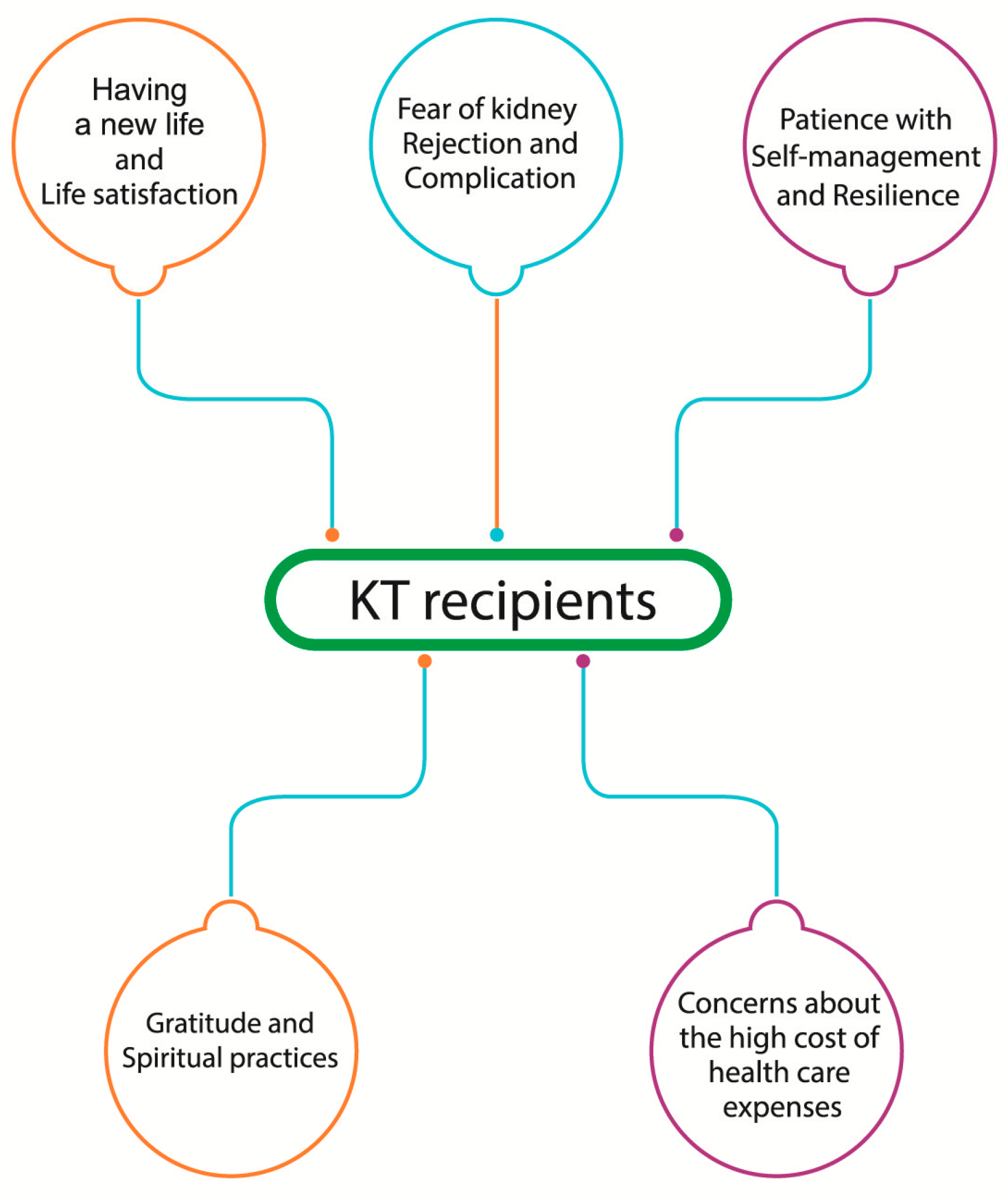

- In a qualitative procedure, five themes emerged with 25 subthemes. The five themes included (1) having new life and life satisfaction, (2) fear of kidney rejection and complications, (3) gratitude and spiritual practices, (4) concerns for high cost to healthcare expenses (5) patience with self-management and resilience. (Table 2).

- Theme 1: Having a new life and life satisfaction:

I am very satisfied with my life now. I am luckier than if I had won the first prize in the lottery. I feel better and healthier, and I am 100% better after 1 year and 8 months of surgery. I have more time to work and sleep well.(P…1)

I had kidney failure from abnormalities in IgA and Hypertension, making it Stage 5 of kidney failure. My 26-year-old sister donated a kidney, so I had a quick kidney transplant without dialysis. I have now been on KT for 3 years and 8 months, and there is no need to use antihypertensive drugs; my IgA has returned to normal in every way, giving me hope in life. I have consulted with my husband and doctor about having children. The doctor said that I can have children, so I am adjusting my immunosuppressant medication and am planning to have children in the near future.(P…24)

- 2.

- Theme 2: Fear of kidney rejection and complications:

I was worried about Kidney rejection and infection because of CMV and BK infections that were detected. I took three different kinds of medication per day. My anxiety has decreased a lot. I am now back on my feet again.(P…10)

I was very stressed and uneasy about kidney rejection and abnormal blood test results. I had to do a kidney biopsy and six plasmapheresis sessions, but now that I’ve gotten through it, I feel much more at ease and think everything is satisfactory.(P…9)

- 3.

- Theme 3: Gratitude feeling and spiritual practices:

To think positively in the face of this misfortune, there was also good fortune, such as having received a kidney transplant from a kind-hearted donor (without having known each other beforehand). There were many doctors taking care of me, including surgeons, immunosuppressant doctors, psychiatrists, and many nurses. There was a Line group network to provide advice on problems 24 h a day, which helped me overcome the difficulties. I felt warm and comfortable when I came to receive treatment at this hospital. I was grateful for the kindness that gave me new life once again.(P…8)

I am very fortunate to have a good wife. In addition to giving me a kidney, she has always taken good care of me. She even went so far as to do things for me. I am mindful of her kindness and will perform good deeds and accumulate merit every month for my wife, the doctors, and the nurses.(P…13)

I read Dhamma books every day without fail, make merit according to Buddhist beliefs, donate money to the poor and hospitals, give alms, pray, meditate, and practice Dhamma at home daily.(P…21)

- 4.

- Theme 4: Concerns about the high cost of healthcare expenses:

The cost of surgery was high, but this hospital operates as a charitable healthcare Institution. The cost here was lower than in other places, but the service provided by the doctors and nurses was excellent. I had to be readmitted for another 7 days to do Plasma pheresis 4 times, costing more than 206,000 Baht. So, I felt very concerned.(P…14)

I was worried that the funds would not be sufficient for the total amount of expenses.(P…24)

- 5.

- Theme 5: Patience with self-management and resilience:

You must be patient and accept whatever may happen. Follow the advice of your doctor and nurses and help yourself as much as possible. Eat clean, cooked, and hot food. Avoid eating green leafy vegetables, seafood, shrimp, and shellfish. Avoid lifting objects that weigh more than 2 kg. Take your medicine on time and follow your doctor’s instructions strictly.(P…11)

I had cystic kidney disease and had to have the cyst pierced through the abdomen to drain it. But now I’m better. The problem is gone. I’m not worried anymore. However, I must be diligent in observing myself and attending check-ups strictly.(P…12)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Relevance to Clinical Practice

5.2. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The Thai Organ Transplantation Society. Report Information on Organ Transplantation for the Year 2023. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1BV05qYumnc7fHaHXv3-cQ9juL9ZCySZm/view (accessed on 5 April 2025). (In Thai).

- Antoun, J.; Brown, D.J.; Clarkson, B.G.; Shepherd, A.I.; Sangala, N.C.; Lewis, R.J.; McNarry, M.A.; Mackintosh, K.A.; Corbett, J.; Saynor, Z.L. Experiences of adults living with a kidney transplant-Effects on physical activity, physical function, and quality of life: A descriptive phenomenological study. J. Ren. Care 2023, 49, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghelichi-Ghojogh, M.; Mohammadizadeh, F.; Jafari, F.; Vali, M.; Jahanian, S.; Mohammadi, M.; Jafari, A.; Khezri, R.; Nikbakht, H.-A.; Daliri, M.; et al. The global survival rate of graft and patient in kidney transplantation of children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2022, 22, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Hemmelder, M.H.; Bos, W.J.W.; Snoep, J.D.; de Vries, A.P.J.; Dekker, F.W.; Meuleman, Y. Mapping health-related quality of life after kidney transplantation by group comparisons: A systematic review. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2021, 36, 2327–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J.H.; Koo, T.Y.; Ro, H.; Cho, J.H.; Kim, M.G.; Huh, K.H.; Park, J.B.; Lee, S.; Han, S.; Kim, J.; et al. Better health-related quality of life in kidney transplant patients compared to chronic kidney disease patients with similar renal function. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Park, G.C.; Park, J.; Kim, J.E.; Yu, M.Y.; Kim, K.; Park, M.; Kim, Y.C.; Kim, D.K.; Joo, K.W.; et al. Disparity in accessibility to and prognosis of kidney transplantation according to economic inequality in South Korea: A widening gap after expansion of Insurance coverage. Transplantation 2021, 105, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knobbe, T.J.; Kremer, D.; Bültmann, U.; Annema, C.; Navis, G.; Berger, S.P.; Bakker, S.J.L.; Meuleman, Y. Insights into health-related quality of life of kidney transplant recipients: A narrative review of associated factors. Kidney Med. 2025, 7, 100986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- De Pasquale, C.; Pistorio, M.L.; Veroux, M.; Indelicato, L.; Biffa, G.; Bennardi, N.; Zoncheddu, P.; Martinelli, V.; Giaquinta, A.; Veroux, P. Psychological and psychopathological aspects of kidney transplantation: A systematic review. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, S.; Tasaki, M.; Saito, K.; Nakagawa, Y.; Ikeda, M.; Takahashi, K.; Tomita, Y. Long-term CMV Monitoring and chronic rejection in renal transplant recipients. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1190794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, S.E.; Knobbe, T.J.; Kremer, D.; van Munster, B.C.; Nieuwenhuijs-Moeke, G.J.; Pol, R.A.; Bakker, S.J.L.; Berger, S.P.; Sanders, J.S.F. Kidney transplantation improves health-related quality of life in older recipients. Transpl. Int. 2024, 37, 12071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, E.L.; Smith, A.R.; Daskin, M.S.; Schapiro, H.; Cottrell, S.M.; Gendron, E.S.; Hill-Callahan, P.; Leichtman, A.B.; Merion, R.M.; Gill, S.J.; et al. Life and expectations post-Kidney transplant: A qualitative analysis of patients’ responses. BMC Nephrol. 2019, 20, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wube, T.B.; Asgedom, S.G.; Mengesha, A.G.; Bekele, Y.A.; Gebrekirstos, L.G. Behind the healing: Exploring the psychological battles of kidney transplant patients: A qualitative insight. Health Sci. Rep. 2025, 8, e70511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbinati, L.; Guerzoni, F.; Napoli, N.; Preti, A.; Esposito, P.; Caruso, R.; Bulighin, F.; Storari, A.; Grassi, L.; Battaglia, Y. Psychosocial determinants of healthcare use costs in kidney transplant recipients. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1158387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkefeld, K.; Bauer-Hohmann, M.; Klewitz, F.; Kyaw Tha Tun, E.M.; Tegtbur, U.; Pape, L.; Schiffer, L.; Schiffer, M.; de Zwaan, M.; Nöhre, M. Prevalence of mental disorders in a German kidney transplant population: Results of a KTx360°-Substudy. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2022, 29, 963–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychological Association. Resilience. Available online: https://dictionary.apa.org/resilience (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Chung, M.H. Qualitative content analysis of the resilience scale for patients with kidney transplantation. J. Ren. Care 2025, 51, e70020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 6th ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2023; pp. 198–215. [Google Scholar]

- Heotis, E. Phenomenological research methods: Extensions of Husserl and Heidegger. Int. J. Sch. Cogn. Psychol. 2020, 7, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norlyk, A.; Martinsen, B.; Dreyer, P.; Haahr, A. Why phenomenology came into nursing: The legitimacy and significance of phenomenology in theory building in the discipline of nursing. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2023, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.; Ozuem, W.; Howell, K.; Ranfagni, S. A step-by-step process of thematic analysis to develop a conceptual model in qualitative research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2023, 22, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikipedia. Gratitude. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gratitude#cite_note-ReferenceB-4 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Vredeveld, P. Gratitude in Buddhism: The Heart of Thanksgiving. Available online: https://www.originalbuddhas.com/blog/gratitude-in-buddhism-the-heart-of-thanksgiving?srsltid=ABOor6QvHM_Pzdcl5_ug_3m5fDLsVEYw1KPz_hH0Tz31eXaOVKFFnQ (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- SHUKRANA. The Common Thread of Gratitude in All Religions. Available online: https://www.shukrana.com/gratitude-in-all-religions (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Diniz, G.; Korkes, L.; Tristão, L.S.; Pelegrini, R.; Bellodi, P.L.; Bernardo, W.M. The effects of gratitude interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Einstein 2023, 21, eRW0371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiwattanasuk, N. Gratitude to the Buddha: The case study of Buddhamahametta Foundation. J. Sirindhornparidhat 2024, 25, 664–676. Available online: https://so06.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/jsrc/article/view/262349 (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Abuzar, M. Muslim and Buddhist gratitude practice: A systematic review of psychological benefit for culturally sensitive mental health interventions. Hamdard Islam. 2025, 48, 89–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ThaiPBS. Understanding the 4 Thai Health Insurance Systems: What Will They Cover in 2025? Available online: https://www.thaipbs.or.th/news/content/352794 (accessed on 8 November 2025). (In Thai).

- Lorenz, E.C.; Egginton, J.S.; Stegall, M.D.; Cheville, A.L.; Heilman, R.L.; Nair, S.S.; Mai, M.L.; Eton, D.T. Patient experience after kidney transplant: A conceptual framework of treatment burden. J. Patient-Rep. Outcomes 2019, 3, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Helanterä, I.; Isola, T.; Lehtonen, T.K.; Åberg, F.; Lempinen, M.; Isoniemi, H. Association of clinical factors with the costs of kidney transplantation in the current era. Ann. Transplant. 2019, 24, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hangto, P.; Srisuk, O.; Chunpeak, K.; Hutchinson, A.; van Gulik, N. Effectiveness of a multidisciplinary self-management education programme for kidney transplant recipients in Thailand. J. Kidney Care 2022, 7, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, S.; Lu, X.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Y. The effect of self-management on patients with chronic diseases: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Kang, C.M. Self-management interventions for kidney transplant recipients: A systematic review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aderinto, N.; Olatunji, G.; Kokori, E.; Ogieuhi, I.J.; Moradeyo, A.; Woldehana, N.A.; Lawal, Z.D.; Adetunji, B.; Assi, G.; Nazar, M.W.; et al. A narrative review on the psychosocial domains of the impact of organ transplantation. Discov. Ment. Health 2025, 5, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, L.; Sun, H.; Gao, Z.; Wang, M.; Hu, M.; Ji, Q.; Guo, L. Psychological resilience and quality of life among middle-aged and older adults hospitalized with chronic diseases: Multiple mediating effects through sleep quality and depression. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Flores, C.J.; García-García, G.; Lerma, A.; Pérez-Grovas, H.; Meda-Lara, R.M.; Guzmán-Saldaña, R.M.E.; Lerma, C. Resilience: A protective factor from depression and anxiety in Mexican dialysis patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, N.; Mizukawa, M.K.; Hashino, A.; Kazawa, K.; Naka, M.; Huq, K.A.T.M.E.; Moriyama, M. Factors influencing self-management behaviors among patients with post-kidney transplantation: A qualitative study of the chronic phase transition. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Items | Participant with DDKT | Participant with LRKT |

|---|---|---|

| Sex: | ||

| Male | 12 | 1 |

| Female | 8 | 4 |

| Age (year): | ||

| 20–30 | 1 | - |

| 31–40 | 1 | 1 |

| 41–50 | 2 | 1 |

| 51–60 | 8 | 2 |

| 61–70 | 6 | 1 |

| >70 | 2 | - |

| Employment status: | ||

| Employed | 14 | 4 |

| Unemployed | 2 | - |

| Retirement | 4 | 1 |

| Educational level: | ||

| Elementary | 4 | 1 |

| High school/Diploma | 1 | - |

| Baccalaureate | 12 | 4 |

| Masters | 2 | - |

| Doctorate | 1 | - |

| Cause of CKD: | ||

| HT, DM, DLP | 11 | 1 |

| Autoimmune disease | 3 | 3 |

| Overweight | 3 | - |

| Kidney disease (RC, FSGS, PKD) | 4 | 1 |

| Unknown | 2 | - |

| Since of KT (ms, ys): | ||

| 7 ms–1 y | 8 | - |

| >1–2 ys | 2 | - |

| >2–3 ys | 3 | 1 |

| >4–5 ys | 4 | 1 |

| >5 ys | 4 | 2 |

| Post KT health condition: | ||

| Infection (CMV, BKV, UTI) | 6 | 1 |

| Complication (Active AMR, DC, LC, RVT, US) | 10 | - |

| None | 4 | 4 |

| Themes | Subthemes |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kusoom, W.; Suwanboriboon, N.; Siewthong, S.; Krongyuth, S.; Hengyotmark, A. Experiences of People Living with a Kidney Transplant: A Phenomenological Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2986. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222986

Kusoom W, Suwanboriboon N, Siewthong S, Krongyuth S, Hengyotmark A. Experiences of People Living with a Kidney Transplant: A Phenomenological Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(22):2986. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222986

Chicago/Turabian StyleKusoom, Wichitra, Narin Suwanboriboon, Sangnapa Siewthong, Sununta Krongyuth, and Arunee Hengyotmark. 2025. "Experiences of People Living with a Kidney Transplant: A Phenomenological Study" Healthcare 13, no. 22: 2986. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222986

APA StyleKusoom, W., Suwanboriboon, N., Siewthong, S., Krongyuth, S., & Hengyotmark, A. (2025). Experiences of People Living with a Kidney Transplant: A Phenomenological Study. Healthcare, 13(22), 2986. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222986