Determinants of Postpartum Sexual Dysfunction in the First Year: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

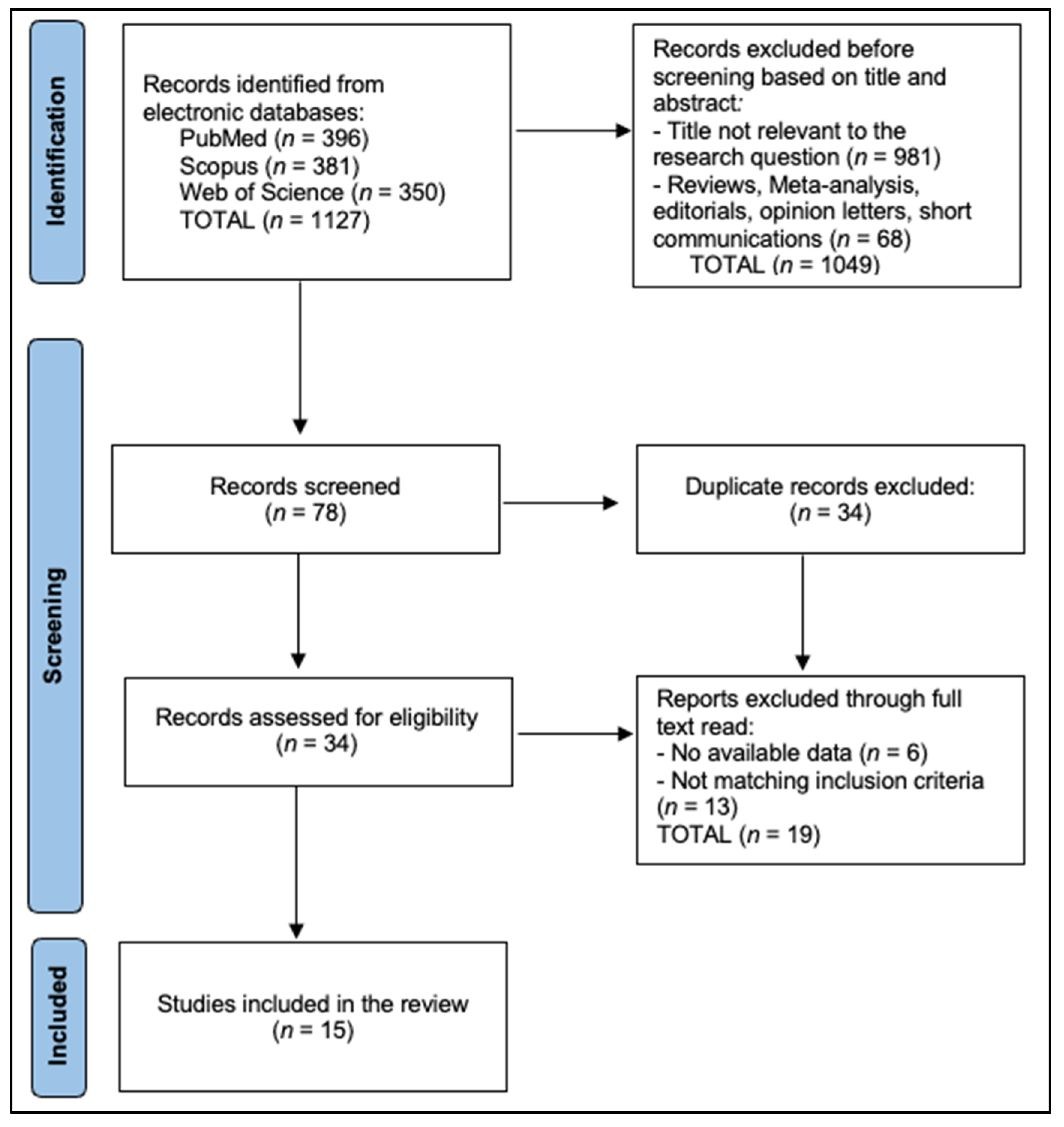

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.6. Data Synthesis

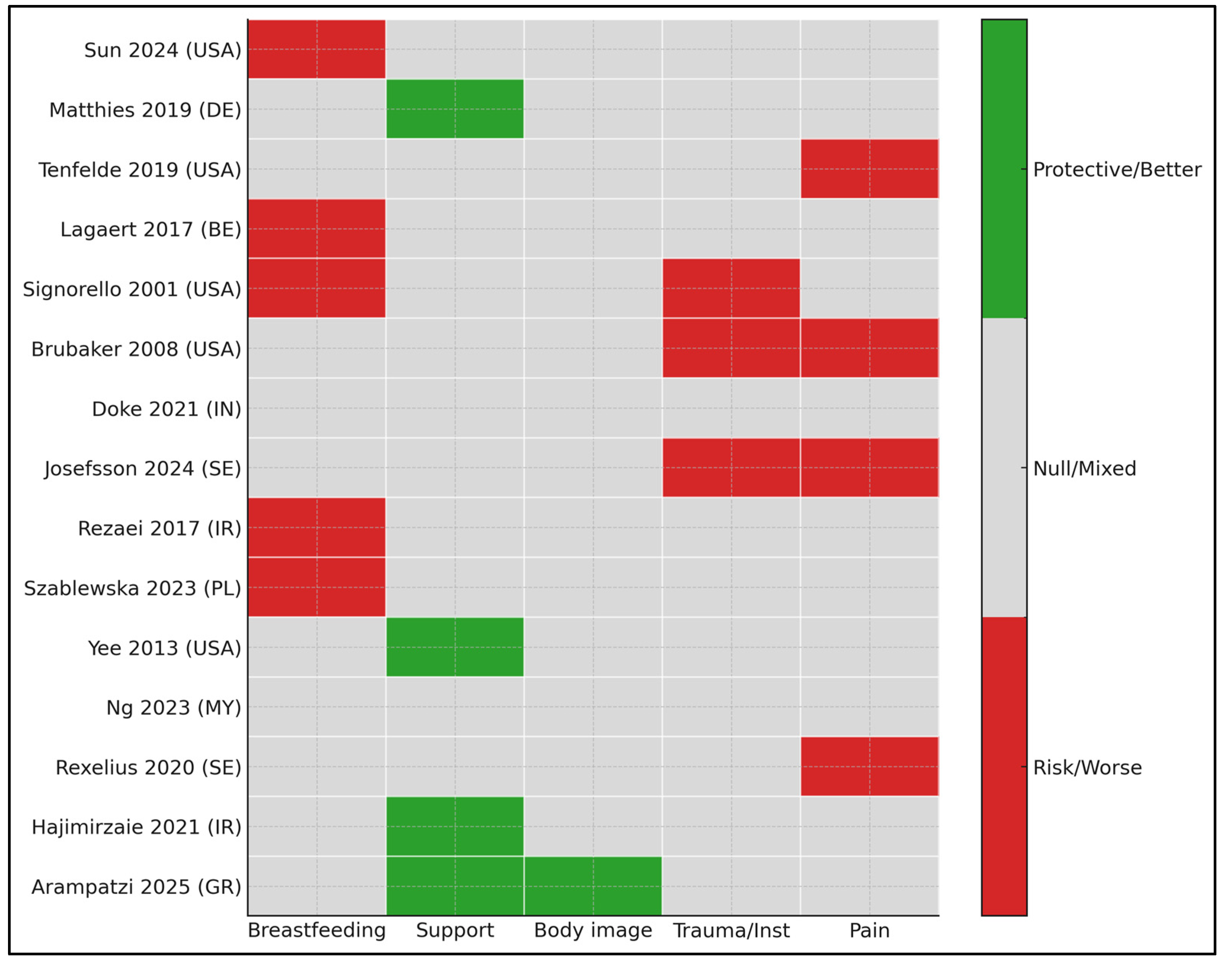

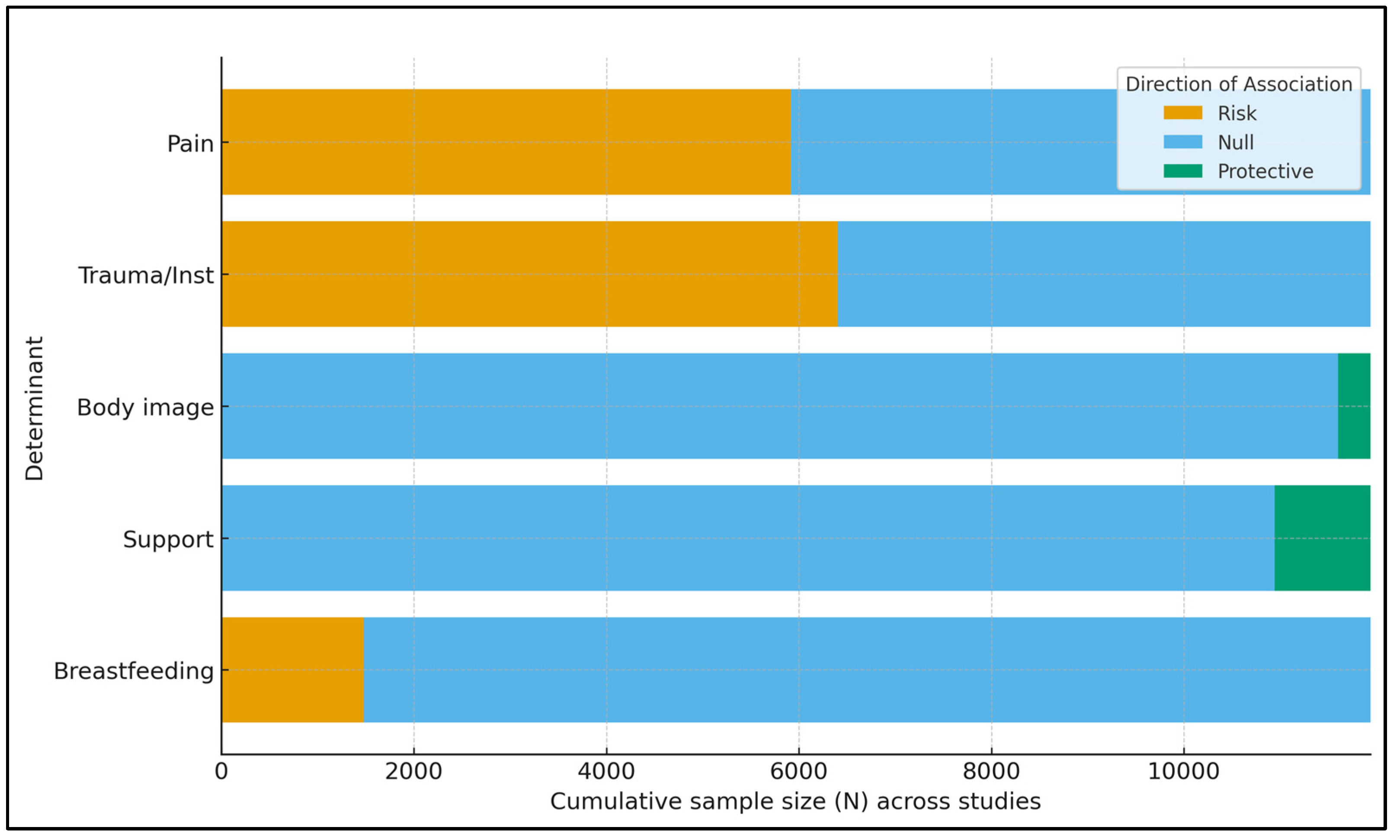

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Evidence

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alligood-Percoco, N.R.; Kjerulff, K.H.; Repke, J.T. Risk Factors for Dyspareunia After First Childbirth. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 128, 512–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rosen, N.O.; Dawson, S.J.; Binik, Y.M.; Pierce, M.; Brooks, M.; Pukall, C.; Chorney, J.; Snelgrove-Clarke, E.; George, R. Trajectories of Dyspareunia from Pregnancy to 24 Months Postpartum. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 139, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- McDonald, E.A.; Gartland, D.; Small, R.; Brown, S.J. Dyspareunia and childbirth: A prospective cohort study. BJOG 2015, 122, 672–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezaei, N.; Behboodi Moghadam, Z.; Tahmasebi, A.; Taheri, S.; Namazi, M. Women’s sexual function during the postpartum period: A systematic review on measurement tools. Medicine 2024, 103, e38975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Guendler, J.A.; Amorim, M.M.; Flamini, M.E.M.; Delgado, A.; Lemos, A.; Katz, L. Analysis of the Measurement Properties of the Female Sexual Function Index 6-item Version (FSFI-6) in a Postpartum Brazilian Population. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obstet. 2023, 45, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wood, S.N.; Pigott, A.; Thomas, H.L.; Wood, C.; Zimmerman, L.A. A scoping review on women’s sexual health in the postpartum period: Opportunities for research and practice within low-and middle-income countries. Reprod. Health 2022, 19, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Belay, H.G.; Yehuala, E.D.; Asmer Getie, S.; Ayele, A.D.; Yimer, T.S.; Berihun Erega, B.; Ferede, W.Y.; Worke, M.D.; Mihretie, G.N. Determinants of early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Womens Health 2024, 20, 17455057241302303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Perelmuter, S.; Burns, R.; Shearer, K.; Grant, R.; Soogoor, A.; Jun, S.; Meurer, J.A.; Krapf, J.; Rubin, R. Genitourinary syndrome of lactation: A new perspective on postpartum and lactation-related genitourinary symptoms. Sex. Med. Rev. 2024, 12, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lev-Sagie, A.; Amsalem, H.; Gutman, Y.; Esh-Broder, E.; Daum, H. Prevalence and Characteristics of Postpartum Vulvovaginal Atrophy and Lack of Association With Postpartum Dyspareunia. J. Low. Genit. Tract Dis. 2020, 24, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jericevic Schwartz, D.; Cervantes, I.; Nwaba, A.U.A.; Duarte Thibault, M.; Siddique, M. Obstetric Anal Sphincter Injury and Female Sexual Dysfunction: A Systematic Review. Urogynecology 2025, 31, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, E.; Falivene, C.; Briffa, K.; Thompson, J.; Henry, A. What is the total impact of an obstetric anal sphincter injury? An Australian retrospective study. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2020, 31, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Starzec-Proserpio, M.; Rejano-Campo, M.; Szymańska, A.; Szymański, J.; Baranowska, B. The Association between Postpartum Pelvic Girdle Pain and Pelvic Floor Muscle Function, Diastasis Recti and Psychological Factors—A Matched Case-Control Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, S.J.; Leonhardt, N.D.; Impett, E.A.; Rosen, N.O. Associations Between Postpartum Depressive Symptoms and Couples’ Sexual Function and Sexual Distress Trajectories Across the Transition to Parenthood. Ann. Behav. Med. 2021, 55, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pauls, R.N.; Occhino, J.A.; Dryfhout, V.L. Effects of pregnancy on female sexual function and body image: A prospective study. J. Sex. Med. 2008, 5, 1915–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahmani, A.; Fallahi, A.; Allahqoli, L.; Grylka-Baeschlin, S.; Alkatout, I. How do new mothers describe their postpartum sexual quality of life? A qualitative study. BMC Womens Health 2023, 23, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Bmj 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Hamilton, F.; Dieter, A.A.; Budd, S.; Getaneh, F. The effect of breastfeeding on postpartum sexual function: An observational cohort study. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2024, 310, 3289–3296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthies, L.M.; Wallwiener, M.; Sohn, C.; Reck, C.; Müller, M.; Wallwiener, S. The influence of partnership quality and breastfeeding on postpartum female sexual function. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2019, 299, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenfelde, S.; Tell, D.; Brincat, C.; Fitzgerald, C.M. Musculoskeletal Pelvic Pain and Sexual Function in the First Year After Childbirth. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2019, 48, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagaert, L.; Weyers, S.; Van Kerrebroeck, H.; Elaut, E. Postpartum dyspareunia and sexual functioning: A prospective cohort study. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2017, 22, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Signorello, L.B.; Harlow, B.L.; Chekos, A.K.; Repke, J.T. Postpartum sexual functioning and its relationship to perineal trauma: A retrospective cohort study of primiparous women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 184, 881–888; discussion 888–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brubaker, L.; Handa, V.L.; Bradley, C.S.; Connolly, A.; Moalli, P.; Brown, M.B.; Weber, A.; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Sexual function 6 months after first delivery. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008, 111, 1040–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Doke, P.P.; Vaidya, V.M.; Narula, A.P.S.; Patil, A.V.; Panchanadikar, T.M.; Wagh, G.N. Risk of non-resumption of vaginal sex and dyspareunia among cesarean-delivered women. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2021, 10, 2600–2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Josefsson, M.L.; Sohlberg, S.; Ekéus, C.; Uustal, E.; Jonsson, M. Self-reported dyspareunia and outcome satisfaction after spontaneous second-degree tear compared to episiotomy: A register-based cohort study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0315899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rezaei, N.; Azadi, A.; Sayehmiri, K.; Valizadeh, R. Postpartum Sexual Functioning and Its Predicting Factors among Iranian Women. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 24, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Szablewska, A.W.; Michalik, A.; Czerwińska-Osipiak, A.; Zdończyk, S.A.; Śniadecki, M.; Bukato, K.; Kwiatkowska, W. Breastfeeding vs. Formula Feeding and Maternal Sexuality among Polish Women: A Preliminary Report. Healthcare 2023, 12, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yee, L.M.; Kaimal, A.J.; Nakagawa, S.; Houston, K.; Kuppermann, M. Predictors of postpartum sexual activity and function in a diverse population of women. J. Midwifery Womens Health 2013, 58, 654–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ng, Y.Y.; Muhamad, R.; Ahmad, I. Sexual dysfunction among six months postpartum women in north-eastern Malaysia. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0284014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rexelius, N.; Lindgren, A.; Torstensson, T.; Kristiansson, P.; Turkmen, S. Sexuality and mood changes in women with persistent pelvic girdle pain after childbirth: A case-control study. BMC Womens Health 2020, 20, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hajimirzaie, S.S.; Tehranian, N.; Razavinia, F.; Khosravi, A.; Keramat, A.; Haseli, A.; Mirzaii, M.; Mousavi, S.A. Evaluation of Couple’s Sexual Function after Childbirth with the Biopsychosocial Model: A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2021, 26, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Arampatzi, C.; Michou, V.; Eskitzis, P.; Andreou, K.; Athanasiadis, L. Factors Associated with Postpartum Sexual Function During the Puerperium Period: A Cross-Sectional Study in Greece. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- O’Malley, D.; Higgins, A.; Begley, C.; Daly, D.; Smith, V. Prevalence of and risk factors associated with sexual health issues in primiparous women at 6 and 12 months postpartum; a longitudinal prospective cohort study (the MAMMI study). BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szöllősi, K.; Szabó, L. The Association Between Infant Feeding Methods and Female Sexual Dysfunctions. Breastfeed. Med. 2021, 16, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smetanina, D.; Alnuaimi, S.; Alkaabi, A.; Alketbi, M.; Hamam, E.; Alkindi, H.; Almheiri, M.; Albasti, R.; Almansoori, H.; Alshehhi, M.; et al. Sexual Dysfunctions in Breastfeeding Females: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanshawe, A.-M.; De Jonge, A.; Ginter, N.; Takács, L.; Dahlen, H.G.; Swertz, M.A.; Peters, L.L. The Impact of Mode of Birth, and Episiotomy, on Postpartum Sexual Function in the Medium- and Longer-Term: An Integrative Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajimirzaie, S.S.; Tehranian, N.; Golabpour, A.; Khosravi, A.; Mousavi, S.A.; Keramat, A.; Mirzaii, M. Predicting postpartum female sexual interest/arousal disorder via adiponectin and biopsychosocial factors: A cohort-based decision tree study. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Fernández, M.J.; de Medina-Moragas, A.J. Comparative study of postpartum sexual function: Second-degree tears versus episiotomy outcomes. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2024, 309, 2761–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- De Souza, A.; Dwyer, P.L.; Charity, M.; Thomas, E.; Ferreira, C.H.; Schierlitz, L. The effects of mode delivery on postpartum sexual function: A prospective study. BJOG 2015, 122, 1410–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutzeit, O.; Levy, G.; Lowenstein, L. Postpartum Female Sexual Function: Risk Factors for Postpartum Sexual Dysfunction. Sex. Med. 2020, 8, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Villani, F.; Petre, I.; Buleu, F.; Iurciuc, S.; Marc, L.; Apostol, A.; Valentini, C.; Donati, E.; Simoncini, T.; Petre, I.; et al. Pelvic Floor Muscle Training vs. Vaginal Vibration Cone Therapy for Postpartum Dyspareunia and Vaginal Laxity. Medicina 2025, 61, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simanauskaitė, A.; Kačerauskienė, J.; Railaitė, D.R.; Bartusevičienė, E. The Impact of Pelvic Floor Muscle Strengthening on the Functional State of Women Who Have Experienced OASIS After Childbirth. Medicina 2025, 61, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick, E.T.; Rosen, N.O.; Kim, J.J.; Kolbuszewska, M.T.; Schwenck, G.C.; Dawson, S.J. Sexual satisfaction mediates daily associations between body satisfaction and relationship satisfaction in new parent couples. Body Image 2024, 51, 101810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillen, M.M.; Markey, C.H. A review of research linking body image and sexual well-being. Body Image 2019, 31, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Determinant | Outcome | Effect (Direction) * | Certainty (GRADE) | Key Reasons for Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perineal trauma/instrumentation | Dyspareunia; sexual activity; sexual function (PISQ-12/FSFI) | Higher risk of dyspareunia; lower sexual activity and sexual function | Moderate | Observational designs; consistent direction of effect; imprecision in exact magnitude; heterogeneity in timing and outcome measures |

| Early perineal or pelvic pain | Dyspareunia; sexual avoidance/distress | Higher risk of dyspareunia and sexual avoidance or distress | Moderate | Observational designs; consistent association between early pain and later sexual symptoms; some residual confounding |

| Breastfeeding (especially exclusive breastfeeding in early months) | Dyspareunia; FSFI total and domain scores | Higher risk of dyspareunia and lower FSFI scores in early postpartum, with attenuation by 12 months | Low–Moderate | Inconsistency across timepoints; heterogeneity in breastfeeding definitions; imprecision; predominantly observational data |

| Partner and family support; positive body image | FSFI total/domains; sexual distress | Better sexual function (higher FSFI) and lower sexual distress | Low–Moderate | Predominantly cross-sectional designs; potential residual confounding; consistent direction of association across settings |

| Postpartum pelvic girdle pain and other musculoskeletal pain | Dyspareunia; global sexual function | Higher sexual pain, greater sexual avoidance, and poorer global sexual function | Moderate | Case–control and cohort designs; consistent association between pain and worse sexual outcomes; some unmeasured confounding |

| # | Study (Year, Country) | Design and Postpartum Timepoint | Determinant(s) | Sexual Outcome(s) | Total n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [17] | Sun et al., 2024 (USA) | Cross-sectional; 5–6 months | Breastfeeding vs. formula; contraception; perineal laceration | FSFI total, DIVA | 125 |

| [18] | Matthies et al., 2019 (Germany) | Cohort; 6 months | Partner relationship quality; breastfeeding | FSFI | 330 (enrolled prenatally) |

| [19] | Tenfelde et al., 2019 (USA) | Cohort; 5–6 months | Musculoskeletal pain; depressive symptoms | Sex activity and bother | 45 |

| [20] | Lagaert et al., 2017 (Belgium) | Prospective cohort; 6 weeks and 6 months | Breastfeeding; parity | FSFI; dyspareunia prevalence | 109 |

| [21] | Signorello et al., 2001 (USA) | Retrospective cohort; 3 and 6 months | Perineal trauma grade; instrumentation; breastfeeding | Dyspareunia; orgasm; satisfaction | 615 |

| [22] | Brubaker et al., 2008 (USA) | Cohort (CAPS); 6 months | OASI vs. none; delivery mode | PISQ-12; sexual activity; pain | 459 sexually active at 6 mo |

| [23] | Doke et al., 2021 (India) | Multisite cohort; 6 weeks and 6 months | Cesarean vs. vaginal; perineal injury; rural residence | Non-resumption; dyspareunia (RR) | 3112 |

| [24] | Josefsson et al., 2024 (Sweden) | Registry cohort; 8 weeks and 12 months | 2nd-degree tear vs. episiotomy; infection; re-suturing; pain | Dyspareunia; satisfaction | 5328 |

| [25] | Rezaei et al., 2017 (Iran) | Cross-sectional; 8 weeks–8 months | Exclusive breastfeeding; parity | FSFI dysfunction (cut-off) | 380 |

| [26] | Szablewska et al., 2023 (Poland) | Cross-sectional; ≤1 year | Breastfeeding practices and sexuality | Sexual life self-report | 253 |

| [27] | Yee et al., 2013 (USA) | Prospective; 12 months | Predictors (delivery, mood, etc.) | Sexual activity; problems | 160 |

| [28] | Ng et al., 2023 (Malaysia) | Cross-sectional; 6 months | Sociodemographic; intercourse frequency | FSFI-6 dysfunction | 429 analyzed |

| [29] | Rexelius et al., 2020 (Sweden) | Case–control; postpartum persistent PGP | Pelvic girdle pain vs. healthy | McCoy Sexuality; dyspareunia | 85 (46 + 39) |

| [30] | Hajimirzaie et al., 2025 (Iran) | Systematic review | Couple dynamics and sexuality | FSFI (women), IIEF (men), multiple scales | NR |

| [31] | Arampatzi et al., 2025 (Greece) | Cross-sectional; ≤1 year | Spousal/family support; body image; lifestyle | FSFI total/domains | 336 |

| Study | Timepoint | Exposure Definition | Sexual Outcome | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sun 2024 (USA) [17] | 5–6 months | Self-reported primarily breastfeeding vs. formula | FSFI total (median, IQR) | 20.8 (IQR 10–24) BF vs. 24.5 (19.5–27.8) FF; p = 0.009; lower FSFI associated with BF, perineal laceration, progestin LARC, single status (multivariable) |

| Lagaert 2017 (Belgium) [20] | 6 weeks and 6 months | Breastfeeding yes/no | Dyspareunia; FSFI | Dyspareunia assoc. with BF at 6 wks (p = 0.045); association not significant at 6 mo; primiparity remained associated at 6 mo |

| Signorello 2001 (USA) [21] | 6 months | Breastfeeding yes/no | Dyspareunia | Breastfeeding ≥4× odds of dyspareunia at 6 mo (OR 4.4; 95% CI 2.7–7.0) |

| Rezaei 2017 (Iran) [25] | 8 weeks–8 months | Exclusive vs. non-exclusive BF | FSFI dysfunction | Exclusive BF aOR 2.47 (1.21–5.03) for dysfunction; primiparity aOR 1.78 |

| Szablewska 2023 (Poland) [26] | ≤12 months | Breastfeeding status | Sexual life self-report | BF associated with lower sexual function measures (narrative; numeric detail NR in abstract) |

| Study | Construct | Instrument (If Any) | Sexual Outcome | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arampatzi 2025 (Greece) [31] | Spousal/family support; body image; lifestyle | FSFI; support/body image scales | FSFI total/domains | Higher support and positive body image → better FSFI; low support/negative body image associated with dysfunction (multivariable) |

| Matthies 2019 (Germany) [18] | Partner relationship quality | FSFI | FSFI | Better partnership quality associated with higher FSFI; breastfeeding and LARC also modeled |

| Hajimirzaie 2025 (Iran) [30] | Couple dynamics | biopsychosocial model (systematic review/secondary synthesis) | biopsychosocial model (systematic review/secondary synthesis) | Relational (biopsychosocial) factors consistently influence postpartum sexual function in both partners, supporting couple-centered care. |

| Ng 2023 (Malaysia) [28] | Frequency of intercourse; sociodemographics | FSFI-6 | FSFI-6 dysfunction | Lower coital frequency strongly associated with FSD (multivariable); cultural context discussed |

| Yee 2013 (USA) [27] | Predictors (mood, delivery, etc.) | Structured survey | Sexual activity/problems | Psychosocial factors predicted sexual activity resumption at 12 months |

| Study | Time | Exposure(s) | Dyspareunia % | FSFI Total | Resumed Sex by X | Other Numeric Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Signorello 2001 (USA) [21] | 3 and 6 months | 2nd-degree; 3rd/4th; instrumentation; BF | 41% (3 months); 22% (6 months) | NR | NR | Vacuum/forceps OR 2.5 for dyspareunia at 6 months; BF OR 4.4 |

| Brubaker 2008 (USA) [22] | 6 months | OASI vs. none; mode | Pain during sex 36% of sexually active individuals | PISQ-12 mean 39 ± 4 | 88–94% sexually active by 6 months (varied by group) | Activity lower after OASI |

| Josefsson 2024 (Sweden) [24] | 12 months | 2nd-degree vs. episiotomy; infection; re-suturing; pain at 8 wks | ~30–35% mild/moderate; 2–4% strong | NR | 83–85% had intercourse last 3 months | Pain at 8 weeks aOR ~4.0 for strong dyspareunia; episiotomy ↑ dissatisfaction (aOR 2.4) |

| Doke 2021 (India) [23] | 6 weeks and 6 months | Cesarean vs. vaginal; perineal injury | ~50% dyspareunia at 6 weeks (vaginal); ~33% at 6 months (vaginal) | NR | Non-resumption higher after CS at 6 weeks (RR 1.14) | Dyspareunia RR after CS 0.59 (6 weeks) and 0.49 (6 months) |

| Rexelius 2020 (Sweden) [29] | Postpartum (months) | Persistent pelvic girdle pain vs. healthy | Higher pain during intercourse (p < 0.001) | McCoy total: group diff NR; regression β −0.41 per depression unit | NR | Sexual avoidance ↑ (p < 0.001) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boarta, A.; Gluhovschi, A.; Craina, M.L.; Marta, C.I.; Dumitriu, B.; Socol, I.D.; Sorop, M.I.; Sorop, B. Determinants of Postpartum Sexual Dysfunction in the First Year: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2977. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222977

Boarta A, Gluhovschi A, Craina ML, Marta CI, Dumitriu B, Socol ID, Sorop MI, Sorop B. Determinants of Postpartum Sexual Dysfunction in the First Year: A Systematic Review. Healthcare. 2025; 13(22):2977. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222977

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoarta, Aris, Adrian Gluhovschi, Marius Lucian Craina, Carmen Ioana Marta, Bogdan Dumitriu, Ioana Denisa Socol, Madalina Ioana Sorop, and Bogdan Sorop. 2025. "Determinants of Postpartum Sexual Dysfunction in the First Year: A Systematic Review" Healthcare 13, no. 22: 2977. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222977

APA StyleBoarta, A., Gluhovschi, A., Craina, M. L., Marta, C. I., Dumitriu, B., Socol, I. D., Sorop, M. I., & Sorop, B. (2025). Determinants of Postpartum Sexual Dysfunction in the First Year: A Systematic Review. Healthcare, 13(22), 2977. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222977