Mental Health and Well-Being of Residents with Parkinson’s Disease in Care Homes: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aim

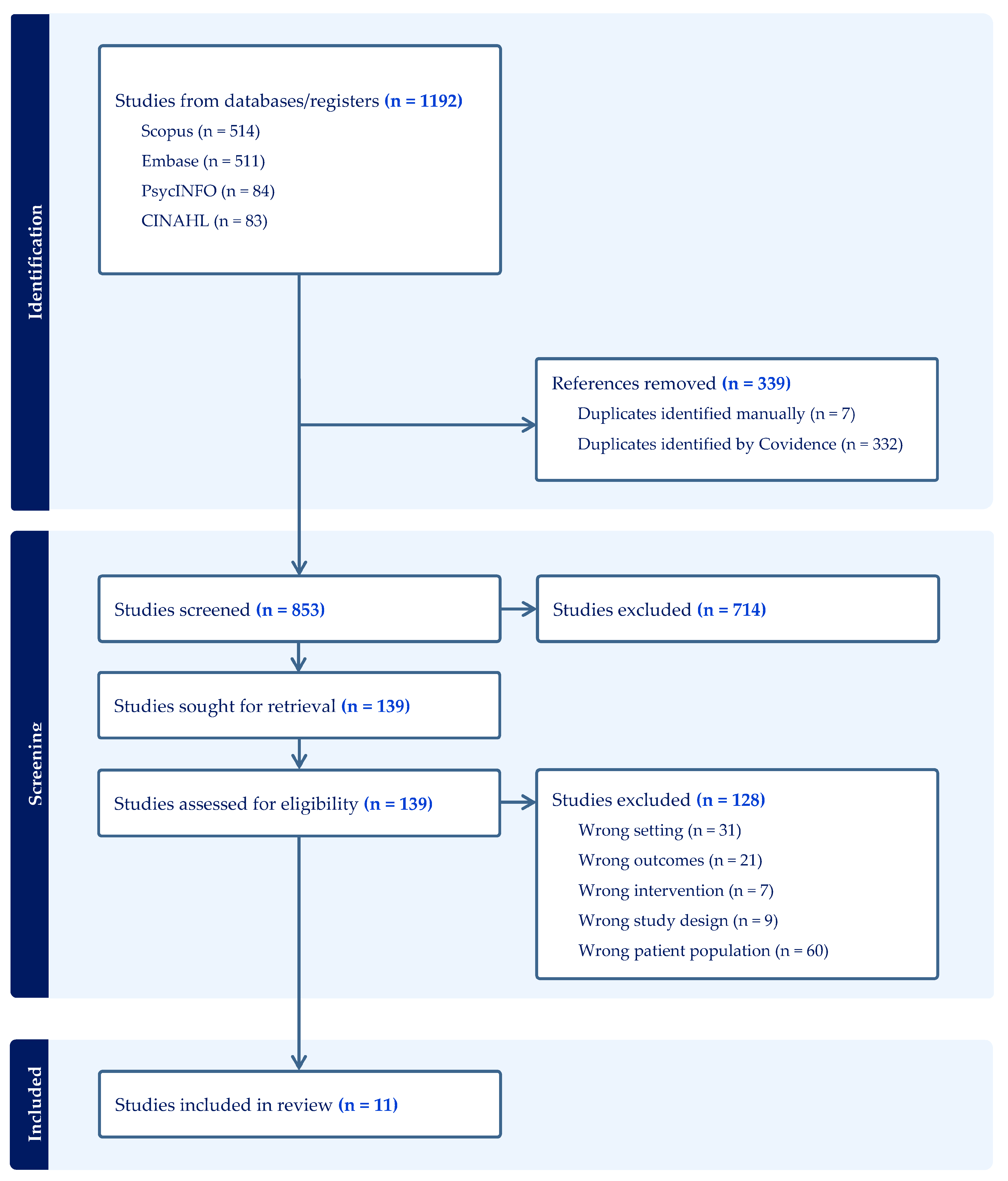

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Criteria for Inclusion

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.2. Quality Appraisal

3.3. Results: Synthesis of Evidence

3.3.1. Theme 1: Complex Mental Health

3.3.2. Theme 2: Experiences of Unmet Mental Health Needs

3.3.3. Theme 3: Organisational and Systemic Factors Influencing Mental Health Support

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PD | Parkinson’s Disease |

| pwPD | People with Parkinson’s Disease |

| NPS | Neuropsychiatric symptoms |

| MMAT | Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool |

References

- Pringsheim, T.; Day, G.S.; Smith, D.B.; Rae-Grant, A.; Licking, N.; Armstrong, M.J.; Roze, E.; Miyasaki, J.M.; Hauser, R.A.; Espay, A.J.; et al. Dopaminergic Therapy for Motor Symptoms in Early Parkinson Disease Practice Guideline Summary. Neurology 2021, 97, 942–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Echchakery, M.; Guennouni, M.; Amane, M.; Omari, M.; El Baz, S.; Achbani, A.; Draoui, A.; Abdelmohcine, A.; El Otmani, I.; Rokni, T.; et al. Parkinson’s Disease: Clinical Manifestations and Risk Factors. In Experimental and Clinical Evidence of the Neuropathology of Parkinson’s Disease; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 121–143. [Google Scholar]

- Darweesh, S.K.; Raphael, K.G.; Brundin, P.; Matthews, H.; Wyse, R.K.; Chen, H.; Bloem, B.R. Parkinson Matters. J. Park. Dis. 2018, 8, 495–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, K.R.; Azulay, J.-P.; Odin, P.; Lindvall, S.; Domingos, J.; Alobaidi, A.; Kandukuri, P.L.; Chaudhari, V.S.; Parra, J.C.; Yamazaki, T.; et al. Economic Burden of Parkinson’s Disease: A Multinational, Real-World, Cost-of-Illness Study. Drugs-Real World Outcomes 2024, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Care, U.K. The Difference Between Residential Care Homes and Nursing Homes. 2022. Available online: https://www.careuk.com/help-advice/what-s-the-difference-between-a-care-home-and-a-nursing-home (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Mavromaras, K.; Knight, G.; Isherwood, L.; Crettenden, A.; Flavel, J.; Karmel, T. How Australian Residential Aged Care Staffing Levels Compare with International and National Benchmarks; Australian Government Department of Health: Canberra, Australia, 2020; Available online: https://www.palliaged.com.au/Portals/5/Documents/Australian_Context/research-paper-1-How-Australian-Residential-Aged-Care-Staffing-Levels-Compare.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Edwards, E.; Kitt, C.; Oliver, E.; Finkelstein, J.; Wagster, M.; McDonald, W.M. Depression and Parkinson’s disease: A new look at an old problem. Depress. Anxiety 2002, 16, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacy, B.; Piotrowski, H.J.; Dewey, R.B., Jr.; Husain, M.M. Severity of depressive and motor symptoms impacts quality of life in Parkinson’s disease patients at an academic movement clinic: A cross-sectional study. Clin. Park. Relat. Disord. 2023, 8, 100180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bock, M.A.; Tanner, C.M. The epidemiology of cognitive function in Parkinson’s disease. Prog. Brain Res. 2022, 269, 3–37. [Google Scholar]

- Mamlekar, H.; Gomes, E.; Ferreira, T. Study of non-motor Symptoms in Parkinsons disease and its impact on their quality of life. IP Indian J. Neurosci. 2023, 9, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khammash, N.; Al-Jabri, N.; Albishi, A.; Al-Onazi, A.; Aseeri, S.; Alotaibi, F.; Almazroua, Y.; Albloushi, M. Quality of life in patients with Parkinson’s disease: A cross-sectional study. Cureus 2023, 15, e33989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, S.; Anderson, T.; Carter, G.; Wilson, C.B.; Stark, P.; Doumas, M.; Rodger, M.; O’shea, E.; Creighton, L.; Craig, S.; et al. Experiences of people living with Parkinson’s disease in care homes: A qualitative systematic review. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 428–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.J.; Callis, J.; Bridger-Smart, S.; Guilfoyle, O. Experiences of Living with the Nonmotor Symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease: A Photovoice Study. Health Expect. 2024, 27, e14124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.-L.; Lee, M.; Huang, T.-T. Effectiveness of physical activity on patients with depression and Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutten, S.; Ghielen, I.; Vriend, C.; Hoogendoorn, A.W.; Berendse, H.W.; Leentjens, A.F.; van der Werf, Y.D.; Smit, J.H.; Heuvel, O.A.v.D. Anxiety in Parkinson’s disease: Symptom dimensions and overlap with depression and autonomic failure. Park. Relat. Disord. 2015, 21, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajan, R.; Brennan, L.; Bloem, B.R.; Dahodwala, N.; Gardner, J.; Goldman, J.G.; Grimes, D.A.; Iansek, R.; Kovács, N.; McGinley, J.; et al. Integrated care in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov. Disord. 2020, 35, 1509–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettany-Saltikov, J.; McSherry, R. How to Do a Systematic Literature Review in Nursing: A Step-by-Step Guide, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: Maidenhead, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- McKeown, S.; Mir, Z.M. Considerations for conducting systematic reviews: Evaluating the performance of different methods for de-duplicating references. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Thematic analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 2017, 12, 297–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.N.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’cAthain, A.; et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inf. 2018, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerkamp, N.J.; Tissingh, G.; Poels, P.J.; Zuidema, S.U.; Munneke, M.; Koopmans, R.T.; Bloem, B.R. Nonmotor symptoms in nursing home residents with Parkinson’s disease: Prevalence and effect on quality of life. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2013, 61, 1714–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarsland, D.; Larsen, J.P.; Lim, N.G.; Janvin, C.; Karlsen, K.; Tandberg, E.; Cummings, J.L. Range of neuropsychiatric disturbances in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1999, 67, 492–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosking, A.; Hommel, A.A.; Lorenzl, S.; Coelho, M.; Ferreira, J.J.; Meissner, W.G.; Odin, P.; Bloem, B.R.; Dodel, R.; Schrag, A. Characteristics of Patients with Late-Stage Parkinsonism Who are Nursing Home Residents Compared with those Living at Home. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 440–445.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtgöz, A.; Genç, M. Spiritual Care Perspectives of Elderly Individuals with Parkinson’s Disease and Formal Caregivers: A Qualitative Study in Turkish Nursing Homes. J. Relig. Health 2024, 63, 2106–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rumund, A.; Weerkamp, N.; Tissingh, G.; Zuidema, S.U.; Koopmans, R.T.; Munneke, M.; Poels, P.J.; Bloem, B.R. Perspectives on Parkinson disease care in Dutch nursing homes. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2014, 15, 732–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lex, K.M.; Larkin, P.; Osterbrink, J.; Lorenzl, S. A Pilgrim’s Journey-When Parkinson’s Disease Comes to an End in Nursing Homes. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armitage, G.; Adams, J.; Newell, R.; Coates, D.; Ziegler, L.; Hodgson, I. Caring for persons with Parkinson’s disease in care homes: Perceptions of residents and their close relatives, and an associated review of residents’ care plans. J. Res. Nurs. 2009, 14, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-P.; Chien, C.-F.; Hsieh, S.-W.; Huang, L.-C.; Lin, C.-F.; Hsu, C.-C.; Yang, Y.-H. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Institutionalized Patients with Parkinson’s Disease in Taiwan: A Nationwide Observational Study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 258. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36673626/ (accessed on 24 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Pigott, J.S.; Bloem, B.R.; Lorenzl, S.; Meissner, W.G.; Odin, P.; Ferreira, J.J.; Dodel, R.; Schrag, A. The Care Needs of Patients with Cognitive Impairment in Late-Stage Parkinson’s Disease. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2024, 37, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.W.; Palmer, J.; Stancliffe, J.; Wood, B.H.; Hand, A.; Gray, W.K. Experience of care home residents with Parkinson’s disease: Reason for admission and service use. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2014, 14, 947–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, B.; Henry, S.R.; Gray, W.K.; Walker, R.W. Care Requirements of a Prevalent Population of People with Idiopathic Parkinson’s Disease. Age Ageing 2009, 39, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallon, A.; Mitchell, G.; Carter, G.; McLaughlin, D.F.; Grimes, C.; Brown Wilson, C. Managing Adversity: A Cross-Sectional Exploration of Resilience in Social Care. BMC Geriatr. 2025, 25, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schick, B.; Mayer, B.; Jäger, M.; Jungwirth, B.; Barth, E.; Eble, M.; Sponholz, C.; Muth, C.-M.; Schönfeldt-Lecuona, C. Emergency Medical Care of Patients with Psychiatric disorders—Challenges and opportunities: Results of a Multicenter Survey. BMC Emerg. Med. 2022, 22, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crooks, S.; Mitchell, G.; Wynne, L.; Carter, G. Exploring the Stigma Experienced by People Affected by Parkinson’s disease: A Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 25. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39754132/ (accessed on 2 July 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caap-Ahlgren, M. Older Swedish women’s Experiences of Living with Symptoms Related to Parkinson’s Disease. J. Adv. Nurs. 2002, 39, 87–95. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12074755/ (accessed on 20 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Chiong-Rivero, H. Patients’ and Caregivers’ Experiences of the Impact of Parkinson’s Disease on Health Status. Patient Relat. Outcome Meas. 2011, 2, 57. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21691459/ (accessed on 17 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Valcarenghi, R.V.; Alvarez, A.M.; Santos, S.S.C.; Siewert, J.S.; Nunes, S.F.L.; Tomasi, A.V.R. The Daily Lives of People with Parkinson’s Disease. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2018, 71, 272–279. Available online: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?pid=S0034-71672018000200272&script=sci_arttext (accessed on 14 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Craig, S.; Cao, Y.; McMahon, J.; Anderson, T.; Stark, P.; Wilson, C.B.; Creighton, L.; Gonella, S.; Bavelaar, L.; Vlčková, K.; et al. Exploring the Holistic Needs of People Living with Cancer in Care homes: An Integrative Review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 3166. Available online: https://pure.qub.ac.uk/en/publications/exploring-the-holistic-needs-of-people-living-with-cancer-in-care (accessed on 18 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Parekh de Campos, A.; Levoy, K.; Pandey, S.; Wisniewski, R.; DiMauro, P.; Ferrell, B.R.; Rosa, W.E. Integrating Palliative Care into Nursing Care. Am. J. Nurs. 2022, 122, 40–45. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36261904/ (accessed on 16 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Finlay, S.; Anderson, T.; Henderson, E.; Wilson, C.B.; Stark, P.; Carter, G.; Rodger, M.; Doumas, M.; O’sHea, E.; Creighton, L.; et al. A Scoping Review of Educational and Training Interventions on Parkinson’s Disease for Staff in Care Home Settings. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 20. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11768021/? (accessed on 9 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Low, L.-F.; Fletcher, J.; Goodenough, B.; Jeon, Y.-H.; Etherton-Beer, C.; MacAndrew, M.; Beattie, E. A Systematic Review of Interventions to Change Staff Care Practices in Order to Improve Resident Outcomes in Nursing Homes. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140711. Available online: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0140711 (accessed on 7 May 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pupíková, M.; Rektorová, I. Non-pharmacological Management of Cognitive Impairment in Parkinson’s Disease. J. Neural Transm. 2019, 127, 799–820. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31823066/ (accessed on 1 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health Care Excellence Overview|Parkinson’s Disease in Adults|Guidance|, N.I.C.E. Nice.org.uk. NICE. 2017. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng71 (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Angelopoulou, E.; Stanitsa, E.; Karpodini, C.C.; Bougea, A.; Kontaxopoulou, D.; Fragkiadaki, S.; Koros, C.; Georgakopoulou, V.E.; Fotakopoulos, G.; Koutedakis, Y.; et al. Pharmacological and Non-Pharmacological Treatments for Depression in Parkinson’s Disease: An Updated Review. Medicina 2023, 59, 1454. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1648-9144/59/8/1454 (accessed on 3 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Wamelen, D.J.V.; Rukavina, K.; Podlewska, A.M.; Chaudhuri, K.R. Advances in the pharmacological and non-pharmacological management of non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease: An update since 2017. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2022, 21, 1786–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonella, S.; Mitchell, G.; Bavelaar, L.; Conti, A.; Vanalli, M.; Basso, I.; Cornally, N. Interventions to Support Family Caregivers of People with Advanced Dementia at the End of Life in Nursing homes: A mixed-methods Systematic Review. Palliat. Med. 2021, 36, 268–291. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34965759/ (accessed on 3 May 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karacan, A.V.; Kibrit, S.N.; Yekedüz, M.K.; Doğulu, N.; Kayis, G.; Unutmaz, E.Y.; Abali, T.; Eminoğlu, F.T.; Akbostancı, M.C.; Yilmaz, R. Cross-Cultural Differences in Stigma Associated with Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review. J. Park. Dis. 2023, 13, 699–715. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37355913/ (accessed on 8 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Turnpenny, A.; Caiels, J.; Whelton, B.; Richardson, L.; Beadle-Brown, J.; Crowther, T.; Forder, J.; Apps, J.; Rand, S. Developing an Easy Read Version of the Adult Social Care Outcomes Toolkit (ASCOT). J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2016, 31, e36–e48. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27778469/ (accessed on 10 May 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Towers, A.M.; Smith, N.; Palmer, S.; Welch, E.; Netten, A. The Acceptability and Feasibility of Using the Adult Social Care Outcomes Toolkit (ASCOT) to Inform Practice in Care Homes. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 523. Available online: https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-016-1763-1 (accessed on 10 April 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rand, S.; Caiels, J.; Collins, G.; Forder, J. Developing a Proxy Version of the Adult Social Care Outcome Toolkit (ASCOT). Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2017, 15, 108. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28526055/ (accessed on 25 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- International Council of Nurses. The ICN Code of Ethics for Nurses. 2021. Available online: https://www.icn.ch/sites/default/files/inline-files/ICN_Code-of-Ethics_EN_Web.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2025).

| Population | (MH “Parkinson Disease”) OR “Parkinson’s Disease” OR PD OR “Parkinsonian” OR “Primary Parkinsonism” OR “Paralysis Agitans” OR “Progressive Supranuclear Palsy” OR “Multiple System Atrophy of Corticobasal Degeneration” |

| Exposure | (MH “Nursing Homes”) OR “Care home” OR “Care homes” OR “Nursing home” OR “Residential home” OR “Residential homes” OR “Long term care facility” OR “Residential Aged Care Facility” OR “Long term care facilities” OR “Homes for the Aged” |

| Outcome | (MH “Depression”) OR (MH “Anxiety”) OR (MH “Quality of Life”) OR (MH “Hallucinations”) OR “Low mood” OR (MH “Symptom Burden”) OR (MH “Psychological Well-Being”) OR “emotional well-being” OR “experience” |

| Criterion | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Individuals diagnosed with PD residing in care homes (e.g., residential, nursing, or long-term care facilities) | Individuals with other neurodegenerative conditions (e.g., dementia) unless data for PD are separately reported |

| Caregivers (formal or informal) of individuals with PD with care home settings (studies including caregivers or professionals were eligible only when providing data relevant to the mental health or well-being of residents with Parkinson’s disease) | Studies that do not involve individuals with PD or their caregivers | |

| Health or social care professionals involved in the care of individuals with PD in care homes | ||

| Exposure | Mental health (e.g., depression, anxiety, psychosis, hallucinations, apathy, agitation, sleep disturbances, cognitive impairment) | Studies focusing exclusively on motor symptoms or unrelated health issues |

| Setting | Care home settings, including residential care, nursing homes, and long-term care facilities | Community-based or outpatient settings, hospitals, or acute care facilities |

| Outcomes | To better understand the state of mental health and well-being among residents with Parkinson’s disease and care delivery | Studies not reporting outcomes related to mental health and well-being |

| Study Design | Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods studies | Editorials, commentaries, opinion pieces without primary data |

| Language | English-language publications | Non-English publications without available translation |

| Publication Date | No restrictions |

| Study | Aim | No. of Participants | Setting | Method of Data Collection | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aarsland et al. (1999) [24] | To assess the range of mental health symptoms in a representative sample of patients with Parkinson’s disease. | 139 A structured interview was conducted with the caregiver of each patient (not the patient themselves) to complete the NPI. ~36 staff members (one per nursing home resident) ~103 family caregivers (for home-dwelling patients). | Nursing homes | Structured interviews with caregivers and patients | A strong association was found between the severity of mental health (such as depression, anxiety, and hallucinations) and the advanced stage of Parkinson’s disease, indicating that these symptoms significantly contribute to reduced well-being in PD patients. |

| Armitage et al. (2009) [29] | To explore and describe the care of persons with Parkinson’s disease (pwPD) who are care home residents. | 24 residents living with Parkinson’s disease across 43 care homes. 45 care plans were analysed to assess how care was documented and planned for pwPD residents. | Care homes | Interviews, review of care plans | Only 13 out of 45 care plans (28%) were accessible to residents or relatives. Only 6 care plans were co-signed by pwPD or relatives. The level of specific written detail about PD was minimal when compared to the relative’s descriptions of the affected person’s needs. |

| Chang et al. (2023) [30] | To investigate the prevalence of risk factors for mental health symptoms in institutionalised patients with PD in Taiwan. | 370 Patients with Parkinson’s disease (pwPD): A total of 370 institutionalised patients with a confirmed diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease were included in the final analysis. These participants were drawn from 266 long-term care service institutions across 22 cities and counties in Taiwan. Caregivers (staff): Although the exact number of caregivers is not stated, each of the 370 patients had at least one caregiver informant involved. | Institutions | Survey conducted in two stages | Depression (14.3%) and anxiety (13.2%) were among the most common disorders in institutionalised PD patients. The study emphasised the need for regular screening and targeted interventions for this population. |

| Hosking et al. (2020) [25] | To determine clinical characteristics and treatment complications of patients with late-stage parkinsonism living in nursing homes compared to those living at home. | 692 Total participants: 692 patients with late-stage parkinsonism Nursing home residents: 194 Living at home: 498 Caregivers: All participants had a caregiver involved (either a family member or professional care staff), as data collection included patient and caregiver input. | Nursing homes | Structured interviews and validated assessment tools | Only cognitive function (MMSE, p = 0.03) and mental health symptoms (NPI-Q, p = 0.01) were significantly worse among nursing home residents, while other measures such as motor severity (MDS-UPDRS-III), depression, anxiety, and dementia staging showed no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05). |

| Kurtgöz and Genç (2024) [26] | To determine the perceptions and experiences of elderly PD patients and caregivers regarding spiritual care. | 23 All 23 participants were interviewed, 8 residents Originally, 14 were approached 3 were excluded due to advanced dementia 3 were excluded due to communication difficulties 15 caregivers were interviewed | Nursing homes | Face-to-face semi-structured interviews interviewed Interviews took place in counselling rooms within the nursing homes | Profound sense of psychological distress among both residents and caregivers, though the exact number of participants reporting this theme was not specified. One resident remarked, “I yearn for spiritual support that makes me feel whole, yet it is never offered here.” |

| Lex et al. (2018) [28] | To examine the medical and nursing demands of residents in late-stage Parkinson’s disease cared for in residential homes. | 9 residents with PD who required support in activities of daily living and five family members. | Nursing homes | Semi-structured ethnographic interviews | All nine participants exhibited severe limitations in daily activities, but some residents reported a degree of contentment with their living situations. This variability in personal coping strategies was evident despite the physical challenges of late-stage PD. |

| Pigott et al. (2023) [31] | To compare care needs and resource use for PD patients with and without cognitive impairment. | 675 Total participants living in a care home or similar setting: 177 out of 675 participants (26.2%) The patient, where feasible A caregiver— either: An informal caregiver (e.g., spouse, child) if the patient lived at home A professional caregiver (e.g., care home staff) if the patient lived in a care home | Community settings | Structured face-to-face interviews with both patients and their caregivers | The study found that patients with cognitive impairment were less likely to consult PD nurses, indicating that cognitive deficits may serve as a barrier to accessing specialised PD care, highlighting the need for tailored care strategies for this group. |

| Porter et al. (2010) [33] | To assess the care requirements of people with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease (PD) and compare them with a similarly aged background population. | 135 patients (83.8%) agreed to participate in the study. 19 patients (14.1%) were living in residential or nursing homes. 116 patients (85.9%) were community-dwelling. | Residential care | Structured questionnaire The study relied entirely on patient self-report, and some data were excluded when cognitive impairment made self-report unreliable. | Patients with cognitive impairment were older, had worse motor scores, and were more likely to live in care homes. Those experiencing visual hallucinations had more advanced disease and poorer quality of life but were equally as likely to live at home as those without hallucinations. |

| Van Rumund et al. (2014) [27] | To explore the unmet needs of nursing home residents with Parkinson’s disease (PD) and assess care quality from the perspectives of residents, caregivers, and healthcare workers. | Patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) or parkinsonism interviewed: 15 nursing home residents 15 informal caregivers (not related to the 15 patients, to ensure diverse perspectives) Focus group discussions were used for: The 35 health care professionals | Nursing homes | Semi-structured interviews were used for: All 15 residents All 15 informal caregivers Five focus groups were conducted: Two with nurses Three with multidisciplinary professionals Each focus group lasted approximately 2 h and followed a topic guide. | Participants (residents, caregivers, and healthcare staff) reported several unmet needs, such as inadequate emotional support and insufficient PD-specific knowledge among staff. These unmet needs highlighted gaps in patient-centred care and the importance of addressing mental health symptoms of PD. |

| Walker et al. (2013) [32] | To investigate factors leading to institutionalisation of PD patients and ongoing care needs in care homes. | 90 patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease or other forms of parkinsonism were included. Types of care: 31 residents (34.4%) were in residential care 48 (53.3%) in nursing care 11 (12.2%) in mixed residential/nursing care | Care homes | Retrospective observational study, using: Review of medical records Documentation of: Hospital attendances Admissions Medication use Disease characteristics Reasons for admission to care Time frame: January 2011 to December 2012 (2-year period before the audit in 2013) | Over one-third of patients were taking antidepressants. Depression in PD was found to be undertreated, with antidepressants potentially increasing fall risks in elderly individuals, already a concern in PD. |

| Weerkamp et al. (2013) [23] | To determine the prevalence of non-motor symptoms in nursing home residents with Parkinson’s disease (PD) and to establish the association with quality of life. | While 73 residents were personally assessed through structured interviews and tests, family or staff were not formally interviewed. Nurse-reported tools like the NPI-NH were used for some symptom assessments. | Nursing homes | Cross-sectional study, standardised assessments | Individuals with PD experienced an average of nearly 13 non-motor symptoms per person, with depressive symptoms observed in 45%. The total non-motor symptoms burden was significantly associated with reduced quality of life (R2 = 0.39). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gillis, A.; Mitchell, G.; Craig, S. Mental Health and Well-Being of Residents with Parkinson’s Disease in Care Homes: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2791. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212791

Gillis A, Mitchell G, Craig S. Mental Health and Well-Being of Residents with Parkinson’s Disease in Care Homes: A Scoping Review. Healthcare. 2025; 13(21):2791. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212791

Chicago/Turabian StyleGillis, Arnelle, Gary Mitchell, and Stephanie Craig. 2025. "Mental Health and Well-Being of Residents with Parkinson’s Disease in Care Homes: A Scoping Review" Healthcare 13, no. 21: 2791. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212791

APA StyleGillis, A., Mitchell, G., & Craig, S. (2025). Mental Health and Well-Being of Residents with Parkinson’s Disease in Care Homes: A Scoping Review. Healthcare, 13(21), 2791. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212791